Abstract

We present a patient with Paracoccidioidomycosis/HIV coinfection which has been investigated because of chronic monoarthritis and mucocutaneous lesions. A biopsy of the synovial membrane and skin revealed structures consistent with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. At diagnosis, the count of CD4 + T cells was 44 cells/mm3. We emphasize the importance of clinical suspicion of Paracoccidioidomycosis in patients with HIV/AIDS who live in or are from risk areas.

Keywords: AIDS-related opportunistic infections, HIV, Paracoccidioidomycosis

INTRODUCTION

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a tropical disease caused by the Paracoccidioides brasiliensis fungus. It has a high prevalence in Latin America, especially in Brazil, where it represents a public health problem due to its high incapacitating potential.1 With the HIV pandemic, a larger number of Paracoccidioidomycosis /HIV coinfection cases was to be expected, since currently the virus has the character of ruralization, occurring in regions where the P. brasiliensis is found. Compared to other mycoses like candidiasis, pneumocystosis, histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis, there are fewer cases of described cases of Paracoccidioidomycosis/HIV coinfection, maybe because Paracoccidioidomycosis is not an AIDS defining disease. We report a fatal case of Paracoccidioidomycosis disseminated in a patient with HIV and a T CD4+ count of 44 cells/mm3.

CASE REPORT

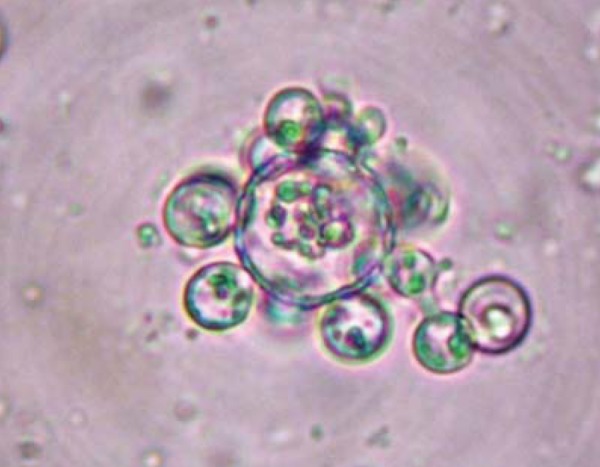

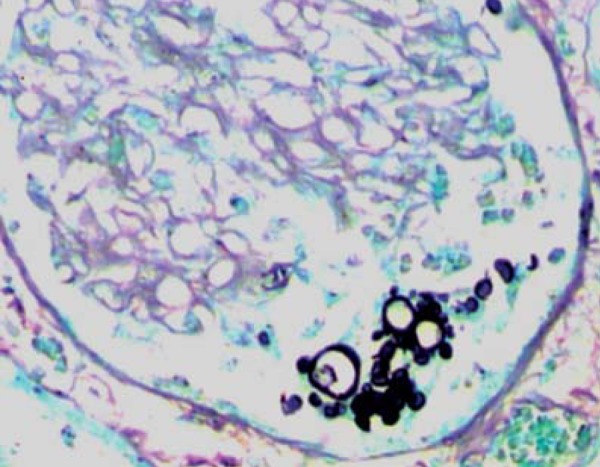

A 28-year-old male from Santarém, Pará, Brazil, with a history of leisure activities in a rural area, tractor driver, a known carrier of the HIV virus since 2010, however without previous follow-up, contacted us for the first time at Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil, for investigation of left knee chronic monoarthritis associated with tegumentary lesions. He had been using zidovudine, lamivudine, lopinavir/ritonavir for three weeks, this being the first antiretroviral regimen used. He had never used prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. He denied being a smoker or alcohol user. He reported that the left knee arthritis appeared after local trauma identified five months before, preceding the tegumentary lesions that appeared two months after the fact. During the clinic exam, polymorphism of skin lesions was noted with pustules of follicular distribution, papules with central necrosis, erythematous-infiltrated plaques covered with pustules and ulcerated plaques, located on the face, trunk, abdomen and limbs, associated with left knee arthritis (Figures 1, 2 and 3A). Oral and genital mucosa were spared. Lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly were not observed. Blood cultures for aerobes, mycobacteria, fungi and leukocyte cream were negative. VDRL resulted non-reagent. The Leishmaniasis screening exam was negative. The analysis of synovial fluid suggested infectious arthritis. Left knee x-ray showed reduction of joint space and osteolytic patellar lesion (Figure 3B). Patient underwent surgical cleansing of joint, biopsy of synovial membrane and skin. Both exams identified round cells, birefringent, with multiple buddings compatible with P. brasiliensis (Figure 4). Culture of synovial tissue confirmed the finding. Complementary propedeutics suggested pulmonary involvement and the Xpert/MTB RIF® sputum test was negative. At the time of diagnosis T CD4+ count was 44 cells/mm3 . Patient was treated with Amphotericin B deoxycholate 50mg/day (cumulative dose of 650mg) but despite the therapy, his clinical condition worsened, progressing to death on the 20th day of hospitalization. Necropsy revealed involvement of lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, adrenals and bone marrow, in addition to the previously described sites (Figure 5).

FIGURE 1.

Necrotic papules and follicular pustules

FIGURE 2.

A and B) Erythematous plaque with follicular pustules on the nose. C) Ulcerated plaque on forehead. D) Ulcerated erythematous infiltrated plaque on the back

FIGURE 3.

A) Left knee monoarthritis. B) Osteolytic lesion in the patella (white arrow)

FIGURE 4.

Biopsy of the synovial membrane: Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (KOH)

FIGURE 5.

Histopathology of the kidney: Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (Grocott)

DISCUSSION

We present a case of Paracoccidioidomycosis disseminated in a patient with HIV. His origin and profession were relevant data on clinical suspicion. Environmental factors arising from deforestation contribute to the increase of Paracoccidioidomycosis cases in the Amazon region.2 Paracoccidioidomycosis has a broad spectrum of manifestations that can be influenced by the environment, parasite pathogenicity and host immune response. The most usual point of entry is the respiratory tract, however the infection may disseminate and any organ may be involved. Bone involvement varies in the literature from 2 - 30% of the cases.3,4,5 The lesion is described as osteolytic and well defined, and may occur in any bone, the most affected ones being those in the thoracic wall. Joint involvement is uncommon and usually due to hematogenic dissemination or contiguity of the adjacent bones; it is observed in about one third of the cases where there is bone lesion.3 Cartilage destruction may occur, with stroke and reduction of joint space. The skin lesions are polymorphic and except for moriform stomatitis of Aguiar-Pupo, there are no cutaneous pathognomonic findings. They can result from hematogenic dissemination, from contiguous lesion or from direct skin inoculation. Cutaneous lesions caused by contiguity to the bone lesion are uncommon.6 Multiple and papulopustular lesions may infer hematogenic dissemination and immunodeficiency. The natural history of Paracoccidioidomycosis in patients with HIV demonstrate direct relationship with the immunosuppression degree, usually occurring with T CD4+ count <200 cells/mm3.7 Paniago et al studied 12 co-infected patients and observed that the fungal disease tends to behave like an opportunistic disease.8 It seems that in this patient, due to severe immunosuppression with the initial pulmonary focus reactivation, there was hematogenic dissemination to the osteoarticular and tegumentary tissues. However, we cannot reject the hypothesis that the previous trauma may have contributed to the onset of fungus in the osteoarticular system during the fungemia phase. Studies about the immunopathogeny of Paracoccidioidomycosis indicate that the immunological response to the fungus depends on the interaction of T CD4+ lymphocytes and polymorphonuclear cells. The cytokines produced by these lymphocytes modulate the phagocytic activity of macrophages and neutrophils and in individuals with adequate immunoresponse, a granulomatous reaction capable of controlling the disease occurs.9,10 We believe that the low T CD4+ cell count may have contributed for an ineffective phagocytic activity, bringing about fungal multiplication and dissemination, which evolved to septic shock and to multiple organ dysfunction. Despite the current antiretroviral therapy efficacy more Paracoccidioidomycosis/HIV co-infection cases are expected with the process of HIV ruralization. Health professionals who treat patients with HIV who live in or are from risk areas ought to be alert, including Paracoccidioidomycosis as a differential diagnosis of similar lesions. This disease may be the first clinical manifestation of severe immunosuppression and if not diagnosed and treated early, it has a high potential for sequelae or death.

Footnotes

Work performed at the Tropical Medicine Foundation (Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado - FMT-HVD), Manaus, Brazil

Financial Support: None

Conflict of Interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Filho FQT, Mendes RP, Colombo AL, Moretti ML, Grupo de Consultores do Consenso em Paracoccidioidomicose Consenso em paracoccidioidomicose. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:297–310. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822006000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abati PAM, Nascimento ABB, Echer PA. Perfil epidemiológico, clínico e laboratorial de indivíduos com diagnóstico de paracoccidioidomicose, atendidos no ambulatório municipal de Santarém Pará de 2000 a 2009; 46 Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical; 2010 Mar 14-18; Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa MAB, Carvalho TN, Araújo CR, Júnior, Borba AOC, Veloso GA, Teixeira KS. Extra-pulmonary manifestations of paracoccidioidomycosis. Radiol Bras. 2005;38:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trad HS, Trad CS, Elias J, Jr, Muglia VF. Radiological review of 173 consecutive cases of paracoccidioidomycosis. Radiol Bras. 2006;39:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amstalden EM, Xavier R, Kattapuram SV, Bertolo MB, Swartz MN, Rosenberg AE. Paracoccidioidomycosis of bones and joints. A clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study of 9 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75:213–225. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199607000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marques SA, Cortez DB, Lastória JC, Camargo RMP, Marques MEA. Paracoccidioidomycosis: Frequency, Morphology, and Pathogenesis of Tegumentary Lesions. An Bras Dermatol. 2007;82:411–417. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benard G, Duarte AJ. Paracoccidioidomycosis: a model for evaluation of the effects of Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection of the natural history of endemic tropical diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1032–1039. doi: 10.1086/318146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paniago AM, de Freitas AC, Aguiar ES, Aguiar JI, da Cunha RV, Castro AR, et al. Paracoccidioidomycosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: review of 12 cases observed in an endemic region in Brazil. J Infect. 2005;51:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortes MR, Miot HA, Kurokawa CS, Marques ME, Marques SA. Immunology of paracoccidioidomycosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:516–524. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dias MF, Mesquita J, Filgueira AL, De Souza W. Human neutrophils susceptibility to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: an ultrastructural and cytochemical assay. Med Mycol. 2008;46:241–249. doi: 10.1080/13693780701824411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]