Abstract

Objective

Self-perceived emotional vitality, intact mood, physical activity and social engagement are recognized as important indicators for lowered rates of morbidity and increased longevity in late-life, but little is known about their underlying neural substrates. This study examined relationships between self-reported levels of general functioning and the combined volume of three integrated prefrontal structures associated with self-perception and emotion.

Design

Cross-sectional

Setting

UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience, Los Angeles, CA

Participants

Depressed (N=43) and comparison (N=41) elderly subjects.

Measurements

Magnetic resonance images of orbitofrontal, gyrus rectus and anterior cingulate gray and white matter volumes were corrected for intracranial volume and combined across structures to form white matter and gray matter scales. Subjects completed the RAND Short-Form 36 Questionnaire, a self-report evaluation of daily functioning. Subscales used for analysis were Physical Function, Energy, and General Health, which were not correlated with depression.

Results

White matter volumes were associated with self-perceptions of Energy for healthy as well as depressed individuals, and gray matter volume was associated with General Health. This latter association was strongest among patients with late-onset of depression, i.e., onset > age 50, although it appeared in all diagnostic groups.

Conclusions

Although mild to moderate atrophy is expected in late-life, prefrontal atrophy may represent changes to neuroanatomical substrates that qualitatively modulate self-perceptions of energy and general health for both depressed and non-depressed persons.

Keywords: limbic, prefrontal, health attitude, elderly, MRI, daily functioning, geriatric, atrophy, orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, gyrus rectus

Increasing the percentage of people who age successfully and require minimal health services would foster independence, activity and productivity among today’s elderly as well as reduce health care utilization. Successful aging is no longer defined as freedom from physical or cognitive decline but now includes psychosocial functioning, freedom from depression, moderate levels of physical activity and self-perceived wellness, which may include some or minimal disability or chronic illness. (See review by Depp & Jeste.1) Individuals who meet these modified criteria would be expected to have lower medical utilization rates than those who do not meet criteria.2

Another aspect of successful aging is a positive perception of one’s general health. The reliability of self-perceptions of health and functioning for estimating future morbidity and mortality was demonstrated over 20 years ago in the Manitoba Longitudinal Study. Self-ratings of health by elderly Canadians predicted seven-year survival better than medical records or self-reported medical conditions.3 In 1997, a review of 27 longitudinal studies demonstrated that respondents’ self-ratings of global health independently predicted mortality.4 The follow-up occurred between 2 and 28 years after baseline and included other known mortality risks, such as number of chronic conditions, functional disability, medications, hospitalizations, and cardiovascular symptoms. Most of the medical information was self-reported, although a few studies included physician examinations and ratings. In studies that used medical evaluations, self-reported global assessment remained an independent predictor of morbidity after controlling for physician assessment. The predictive value of self-perceived wellness is equally important among institutionalized people.5

Among those 75 and older, about 30 percent suffer depressive symptoms, and the rates are higher in rural areas than urban areas.6,7 Depressive symptoms work against successful aging by reducing daily functioning more than chronic pain,8 decreasing performance on basic activities of daily living 9,10 and on independent activities of living (e.g., shopping, meal-preparation, yard-work, paying bills),11 and reducing the likelihood of recovering independent functioning after stroke.12 Depression is a risk factor for deterioration in multiple serious medical conditions (e.g., cancer, Parkinson’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease13–15) and death within 3 to 10 years.16,17

The orbitofrontal cortex is associated with both depression and self-perception. Functional magnetic resonance imaging has shown that the medial orbitofrontal region is activated in tasks requiring direct appraisal of self-beliefs,18 reflection about one’s own personality,19 and adoption of a first-person perspective.20 Anterior and posterior cingulate were noted in some studies as additional areas of activation with self-focused tasks.21–23 The orbitofrontal is also associated with emotional processing via bidirectional connections with the amygdaloid complex. The densest connections are to the posterior medial orbitofrontal,24 which forms part of a “limbic lobe” that also connects with memory-related anterior temporal structures.25,26 The anterior orbitofrontal, on the other hand, is part of another neural circuit that has rich cortico-cortical connections with multisensory areas in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.27 Depressed elderly patients have reduced cortical thickness in the orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate and gyrus rectus regions compared to a comparison group, and the difference is greatest among late-onset patients.28,29 The confluence of emotional, sensory and self-reflective processing in this prefrontal region make it an area of interest for understanding self-perceptions of well-being and feelings of vitality during the aging process for healthy and depressed elderly people.

This study investigated the relationship between volumes of the combined orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate and gyrus rectus regions – referred to here as the prefrontal region – and subjective feelings of general health and daily functioning. Although the anterior cingulate is not normally considered a structural part of the orbitofrontal cortex, it has robust connections with the orbitofrontal cortex particularly via the gyrus rectus. The gyrus rectus can be conceptualized as an extension of the cingulate tissue into the orbitofrontal30 because it shares cytoarchitecture with the anterior cingulate. We hypothesized that self-reported indices of daily functioning would be associated with white and gray matter volumes of the prefrontal region for healthy subjects as well as depressed subjects, although depression diagnosis was expected to add additional explanation to self-perceived functioning. We were also interested in examining whether the age of onset of depressive symptoms, i.e., early- versus late-onset, modulated the self-perceived functional status.

Methods

Subjects

Elderly community-dwelling residents (43 depressed and 41 comparison) were recruited for a larger NIMH-funded study of late-life depression. Exclusionary criterion for dementia was based on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) 31 score ≤ 24 and assessment by a geriatric psychiatrist. Other exclusionary criteria were determined by self-report: chronic neurological or endocrine disease; head trauma or lifetime loss of consciousness of any duration; unstable medical illness requiring recent hospitalization; contraindications for neuroimaging; transient ischemic attack, stroke or myocardial infarction; history or evidence of psychotic symptoms; concurrent psychiatric disorder or Axis 1 disorder other than depression; recent change in medication.

Patients were diagnosed per DSM-IV criteria for major depression. All patients were free of antidepressants, antipsychotics and antianxiety agents for a minimum of two weeks before the study, but none were removed from medication for this study. Patients remained on standard treatment regimens for stable comorbid medical disorders. After a complete description of the study to the subjects, written and informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UCLA Medical Center.

Procedures

Volunteers were screened by research assistants who administered the MMSE, Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis of Axis I Disorders (SCID), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) 32 and RAND 36-Item Health Survey (SF-36).33 Subjects met with a licensed geriatric psychiatrist for clinical review of Axis 1 disorders and completed a Cerebrovascular Risk Factor Assessment (CVRF) 34 and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS),35 a commonly used measure for geriatric patients that quantifies comorbid medical burden on seven major organ systems. Volunteers completed an EKG and standard battery of laboratory tests (complete and differential blood counts; hemocrit, electrolyte and markers of hepatic, renal and thyroid markers). Depressed patients scored ≥15 on the 17-item HAM-D (M= 17.65 ± 2.93, range 15 to 29). Patients were classified as early- (< 50 years of age at onset) (N=25) or late-onset (≥ 50 years of age at onset) (N=18) per self-report.

MRI Methods

The MRI methods were first reported by Ballmaier and colleagues and are briefly reviewed here.28 Subjects were imaged with a 1.5-T Signa MRI scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee) that used a coronal T1-weighted three dimensional (3D) spoiled gradient/recall acquisition (SPGR) in the steady state with the following parameters: repetition time (TR)=20 msec; echo time (TE)=6 msec; flip angle=45°; 1.4-mm slice thickness without gaps; field of view (FOV)=22 cm; number of excitations (NEX)=1.5; matrix size=256x256 mm; in-plane resolution=0.859375×0.859375.

Image Analysis

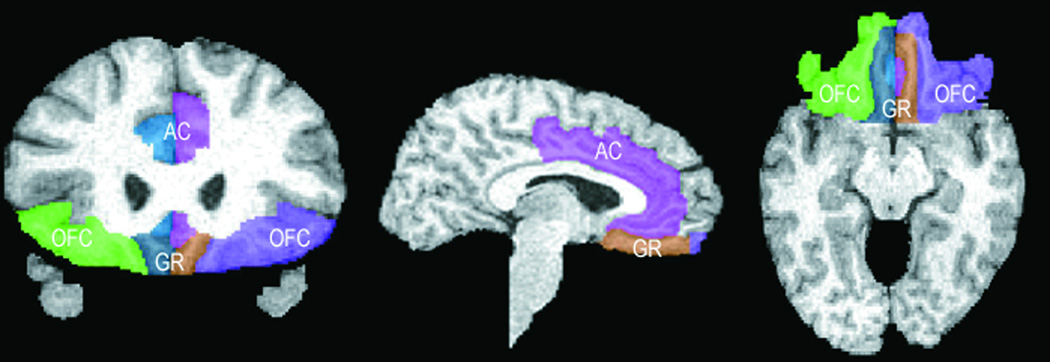

Images were initially masked to remove nonbrain tissue and cerebellum. Brain volumes were corrected for signal intensity inhomogeneities, aligned, and placed into stereotaxic coordinates without scaling to correct for head position. Fully automated tissue segmentation was then applied to the brain volumes, where voxels were classified as gray or white matter or cerebrospinal fluid. A high-resolution shape representation of the cortex was extracted for each subject with automated software.36 These surface/shape extractions were used to aid in delineation of the prefrontal region. See Figure 1. Total intracranial volume was calculated on the intracranial space within – but not including – the menenges down to the last horizontal slice showing the first cerebellar tissue, which occurred at approximately the first spinal disc.

Figure 1.

Frontal Areas Delimited as OFC, Anterior Cingulate and Gyrus Rectus.

OFC = orbitofrontal, AC = anterior cingulate, GR = gyrus rectus

Note. The ventral curve of the anterior cingulate (colored pink and blue-green) can be seen next to the gyrus rectus in the first and last drawings.

Anatomical Boundaries

Details of the written anatomical protocols can be found on the World Wide Web at http://www.loni.ucla.edu/NCRR/protocols.aspx. All anatomical delineations were reconciled using each individual’s three-dimensional surface model and three planes to corroborate sulcal and subregion identity. Delineations were also verified by using two neuroanatomical atlases. Intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability of gray matter, white matter, and CSF volumes, as well as total volumes in all subregions ranged between 0.84 and 0.92 (n=10).

Functional Tests

Function was assessed with the SF-36 developed by RAND Corporation,33 a self-report health survey with 36 questions yielding a profile of functional health and well-being across eight subscales. Three subscales were of interest: Physical Functioning, Energy, and General Health. The Physical Function scale asks about self-perceived limitations for participating in vigorous activities such as running or participating in strenuous sports, or moderate activities such as pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, playing golf or climbing several flights of stairs. The Energy subscale queries how often in the past 4 weeks “Did you feel full of pep/energy/ or feel worn out/ tired.” The General Health subscale assesses how true or false counterbalanced statements are for the participant: “I seem to get sick a little easier than other people - I am as healthy as anybody I know, I expect my health to get worse - my health is excellent” and a general personal rating of health at the time of the assessment. The Emotional Well-Being subscale queries feelings of mood and anxiety and has shown good sensitivity and specificity for the identification of depression in a community-dwelling sample of elderly and was expected to overlap with HAM-D scores. Two other scales, Social Functioning and Bodily Pain, would be examined for independence from HAM-D.

Statistical Analyses

Sample demographic characteristics were examined with ANOVAs and χ2 tests. For variables with significant ANOVA results, follow-up t-tests contrasted each patient group to the comparison group. Anatomical and functioning indices were tested with ANCOVAs using age and sex are covariates, and follow-up t-tests again contrasted patient groups to the comparison group. Three subscales had significant intercorrelations with the HAM-D scale for depressed patients and were dropped from further analysis (Emotional Well-Being (r= −.31, df=43, p= .04), Social Functioning r= −.40, df=43, p< .01), and Bodily Pain (r= −.36, df=43, p=.02)). Remaining subscales (Physical Function, Energy, Physical Health) were expected to show bimodal distribution given the different levels of functioning in the comparison and depressed groups. Examination of the scatterplots showed appropriate distribution for bimodal analysis. We constructed dichotomous (high and low) functioning variables based on cutoff points at which 95% of the comparison group functioned above and 5% functioned below the selected point for each subscale. The resulting cutoff points were 65 for Physical Functioning, 41 for Energy levels, and 65 for General Health on 0–100 point scales.

White and gray matter volumes were transformed into ratios based on intracranial volume. This transformation adjusts for head size and is a rough marker of the degree of atrophy based on the reduction in brain tissue compared to original cranial volume. Gray and white matter ratios of the three structures were averaged to form two aggregated scales. Three hierarchical logistic regression analyses predicting function were computed in which age, education and diagnosis were entered on the first step along with contrast terms for late-onset depression to the comparison group and to early-onset depression. Second, the number of reported systems on the CIRS evaluation was entered to determine the explanatory power of physician rated medical comorbidity. Gray and white matter volume ratios were entered third to determine if volumes explained any additional variance after the demographic and medical variables. Last, interaction terms for time of onset (early versus late) by white and gray matter volumes were entered to determine if there were morphometrically significant differences across onset groups.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in between depressed patients and comparison subjects on handedness, ethnicity, education, or CVRF (Table 1). Patient subgroups did not differ on severity of depression per the HAM-D. There were differences across the three groups on age, MMSE, sex, and CIRS, gray matter volume and functioning on the three SF-36 subscales. Early-onset patients were younger than the comparison group, and late-onset patients scored lower on the MMSE and reported more categories of symptoms on the CIRS. Both early- and late-onset patients differed from the comparison group on gray matter volumes and level of functioning on the RAND Short Form scales.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data of Participants with and without Depression

| Comparison Subjects N=41 |

Early-Onset Depression N= 18 |

Late-Onset Depression N= 25 |

Value | df | Analyses p |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72.20 (±7.27) | 67.44 (± 5.87)* | 73.00 (± 8.22) | F=3.48 | 2,81 | .04 |

| Mini Mental State Examination | 29.51 (±0.81) | 28.88 (± 1.45) | 28.60 (± 1.50)* | F=4.92 | 2,80 | .01 |

| Sex (Female/Male) | 20/21 | 15/3 | 18/7 | χ2=7.63 | 2 | .02 |

| Handedness (Right, %) | 38 (93%) | 16 (89%) | 23 (92%) | χ2= 2.44 | 6 | .88 |

| Ethnicity (% White) | 32 (78%) | 16 (88%) | 18 (72%) | χ2=7.08 | 8 | .53 |

| Education | 15.49 (±2.64) | 15.00 (± 2.50) | 14.56 (± 2.63) | F=1.34 | 2,81 | .27 |

| CIRS | 2.83 (±2.28) | 4.33 (± 2.25) | 5.00 (± 3.25)* | F=5.01 | 2,80 | .01 |

| Age of Onset | -- | 26.78 (± 12.93) | 66.54 (± 10.77) | -- | -- | -- |

| Hamilton Depression | -- | 17.78 (± 2.78) | 18.12 (± 3.61) | t= −0.28 | 41 | .78 |

| CVRF | 5.19 (± 4.78) | 4.76 (± 2.99) | 6.13 (± 4.47) | F= 0.56 | 2,75 | .58 |

| Total Intracranial Volume (cc) | 1311.71 (±152.96) | 1285.32 (± 146.93) | 1294.07 (± 125.99) | F= 0.34 | 2,81 | .71 |

| White Matter Volume (cc) / ICV | .00456 (±.00060) | .00448 (± .00049) | .00428 (± .00093) | F= 1.21 | 2,75 | .30 |

| Gray Matter volume (cc) / ICV | .01048 (±.00102) | .00936 (± .00106)** | .01005 (± .00120)** | F= 6.40 | 2,75 | <.01 |

| SF Physical Functioning | 92.20 (±11.94) | 72.35 (± 14.30)** | 67.60 (± 29.23)** | F= 14.53 | 2,80 | <.01 |

| SF Energy/Fatigue | 76.10 (±19.25) | 22.10 (± 15.92)** | 29.60 (± 18.25)** | F= 84.27 | 2,80 | <.01 |

| SF General Health | 87.56 (±9.75) | 55.00 (± 19.70)** | 60.45 (± 19.97)** | F= 37.05 | 2,80 | <.01 |

Note. CIRS = Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, Geriatrics. CVRF = Cardiovascular Risk Factor adjusted for age. SF = Short Form. ICV = Intracranial Volume. Variables with significant ANOVA differences were followed with t-tests contrasting each patient group to the comparison group

p<.05

p<.01.

ANCOVA analyses for anatomical measures controlled for age and sex, and corrected for total intracranial volume by dividing the absolute volumes (cc) by intracranial volume (cc). RAND Short-Form functioning analyses used the continuous raw scores and controlled for age and sex.

When the two patient subgroups were contrasted for differences using follow-on t-tests, the only differences appeared in age [t (df 1,41) = −5.55, p= .02] and gray matter [t (df 1,41) = −.01, p<.01].

Age and CIRS were used as covariates in the logistic regression analyses, as was education, which was decided a priori to contribute to functional status based on current literature.37–39 Correlations indicated that education was correlated with Energy for the comparison group (r= −.351, df=41, p=.03) and with General Health for depressed patients (r= −.32, df=43, p < .05). MMSE did not correlate with any scale.

Bivariate Logistic Regression Models

In the first analysis, Physical Function was predicted well by age and diagnosis. See Table 2. Self-perceived Physical Function scores among late-onset depressed were significantly lower than comparison individuals (χ2[df 1] = 4.1, p=.04) but not early-onset depressed patients (χ2[df 1] = 2.1, p=.15). The addition of CIRS categories did not add significantly to the explanatory power of the model (χ2[df 1] = 2.84, p=.09). Adding gray and white matter volumes and their interactions did not improve the model (χ2[df 2] = .25, p=.88, and χ2[df 4] = 6.14, p=.19, respectively). In the final analysis, variance was spread over all predictors and nothing emerged as independently significant.

TABLE 2.

Logistic Regression Model of Clinical, Demographic and Anatomical Factors that Contribute to Patients’ Perceptions of Physical Function.

| Hierarchical Regression Models | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit | 1st STEP OF MODEL |

2nd STEP OF MODEL |

3rd STEP OF MODEL |

4th STEP OF MODEL |

||||

| χ2[df 4]. = 14.09, p = .007 | χ2[df 5] = 16.93, p = .005 | χ2[df 7] = 17.17, p = .016 | χ2[df 11] = 23.318, p =.016 | |||||

| VARIABLES | B | p | B | p | B | p | B | p |

| Age | −.11 | .03 | −.07 | .23 | −.08 | .22 | −.08 | .25 |

| Education | −.07 | .61 | −.08 | .57 | −.09 | .55 | −.12 | .46 |

| Diagnostic Groups | .01 | .06 | .08 | .78 | ||||

| Late-onset vs Comparison | 1.84 | .04 | 1.43 | .13 | 1.42 | .14 | 8.16 | .53 |

| Late-onset vs Early-onset | −1.19 | .15 | −1.09 | .21 | −1.34 | .20 | 4.44 | .62 |

| CIRS categories | −.33 | .11 | −.33 | .11 | −.40 | .09 | ||

| White matter (cc) /ICV | 183.29 | .73 | 342.15 | .62 | ||||

| Gray matter (cc) /ICV | −170.08 | .67 | 80.21 | .88 | ||||

| †White Matter Interactions | .31 | |||||||

| †Gray Matter Interactions | .14 | |||||||

Groups’ differences were not reported for nonsignificant interactions.

The second bivariate regression for reported levels of Energy showed a good fit of the model to the data when age, education and diagnosis were entered (Table 3) although only diagnosis was an independent predictor. One interaction emerged in which late-onset depressed patients had lower scores than comparison individuals (χ2 [df 1] = 19.00, p<.01) but not early-onset depressed patients (χ2[df 1] = 2.94, p=.09). In the second step when CIRS entered the equation, neither age, education nor CIRS was independently associated with Energy levels. In the 3rd step the addition of brain volumes significantly increased the explanatory power of the model (χ2 [df 2] = 7.90, p=.02) although only white matter volume was significantly associated with Energy scores (χ2[df 1] =5.26, p=.02). There were no significant interactions. In the final equation, the combination of variables did an excellent job of explaining the variance in Energy levels, (χ2[df 4,11] =73.31, p<.01), but only white matter volume independently predicted reported Energy level (p=.01).

TABLE 3.

Logistic Regression Model of Clinical, Demographic and Anatomical Factors that Contribute to Patients’ Perceptions of Energy.

| Hierarchical Regression Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit | 1st STEP OF MODEL |

2nd STEP OF MODEL |

3rd STEP OF MODEL |

4th STEP OF MODEL |

||||

| χ2[df 4] = 55.86, p = .000 | χ2[df 5] = 58.06, p=.000 | χ2[df 7] = 66.036, p=.000 | χ2[df 11] = 73.31, p =.000 | |||||

| VARIABLES | B | p | B | p | B | p | B | p |

| Age | −.11 | .06 | −.07 | .29 | −.05 | .47 | −.02 | .84 |

| Education | −.19 | .24 | −.24 | .16 | −.26 | .19 | −.17 | .43 |

| Diagnostic Groups | <.01 | <.01 | <.01 | .23 | ||||

| Late-onset vs Comparison | 4.31 | <.01 | 4.09 | <.01 | 4.21 | <.01 | −5.60 | .78 |

| Late-onset vs Early-onset | −1.77 | .09 | −1.88 | .08 | −2.47 | .08 | 37.75 | .10 |

| CIRS categories | −.40 | .17 | −.65 | .09 | −1.00 | .06 | ||

| White matter (cc) /ICV | 1481.38 | .02 | 2048.70 | .01 | ||||

| Gray matter (cc) /ICV | 160.89 | .69 | 650.67 | .34 | ||||

| †White Matter Interactions | .30 | |||||||

| †Gray Matter Interactions | .94 | |||||||

Groups’ differences were not reported for nonsignificant interactions.

As with the first analyses, the initial independent variables of age, education and diagnosis produced a significant fit for perceptions of General Health (Table 4). Both diagnosis (χ2[df 2] = 18.47, p<.01) and education (χ2[df 1] = 6.13, p=.01) were independently related to General Health. There was also an interaction in which late-onset depressed patients had lower scores than the comparison group (χ2[df 1] = 14.62, p<.01) but not early-onset depressed patients (χ2 [df 1] = 2.52, p<.11). The addition of white and gray matter volumes did not improve the explanatory power (χ2[df 2] = 4.64, p=.10), but the addition of interaction terms clarified the model. In the final step, white matter ratios trended toward significance (χ2[df 1] = 3.21, p=.07) and gray matter ratios were significant (χ2 [df 1] = 4.22, p=.04) indicating an effect across diagnostic groups of brain volumes on perceptions of well-being. Follow-up analysis showed the association between prefrontal gray matter and General Health is stronger among late-onset depressed patients (t= 3.77, p<.01) than comparison group (t= −1.46, p=.16) or early-onset depressed patients (t= −1.39, p=.19).

TABLE 4.

Logistic Regression Model of Clinical, Demographic and Anatomical Factors that Contribute to Patients’ Perceptions of General Health.

| Hierarchical Regression Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Fit | 1st STEP OF MODEL |

2nd STEP OF MODEL |

3rd STEP OF MODEL |

4th STEP OF MODEL |

||||

| χ2[df 4] = 40.82, p =.00 | χ2[df 5] = 40.84, p =.00 | χ2[df 7] = 45.48, p=.00 | χ2(df =11) =59.94, p=.00 | |||||

| VARIABLES | B | p | B | p | B | p | B | p |

| Age | −.08 | .13 | −.07 | .19 | −.055 | .39 | −.10 | .24 |

| Education | −.42 | .01 | −.42 | .01 | −.441 | .02 | −.74 | .01 |

| Diagnostic Groups | <.01 | <.01 | <.01 | .03 | ||||

| Late-onset vs Comparison | 3.87 | <.01 | 3.85 | <.01 | 3.84 | <.01 | 54.32 | <.01 |

| Late-onset vs Early-onset | −1.35 | .11 | −1.35 | .11 | −1.31 | .20 | 30.79 | .05 |

| CIRS categories | −.024 | .91 | −.048 | .83 | −.104 | .69 | ||

| White matter (cc) /ICV | 845.99 | .11 | 1837.10 | .07 | ||||

| Gray matter (cc) /ICV | 287.31 | .39 | 2435.56 | .04 | ||||

| White Matter Interactions | .40 | |||||||

| Late-onset vs. Comparison | −2657.41 | .18 | ||||||

| White matter: Late-onset vs Early-onset | −150.84 | .93 | ||||||

| Hierarchical Regression Model | ||||||||

| Model Fit | 1st STEP OF MODEL |

2nd STEP OF MODEL |

3rd STEP OF MODEL |

4th STEP OF MODEL |

||||

| χ2[df 4] = 40.82, p =.00 | χ2[df 4] = 40.82, p =.00 | χ2[df 4] = 40.82, p =.00 | χ2[df 4] = 40.82, p =.00 | |||||

| Gray Matter Interactions | .05 | |||||||

| Late-onset vs Comparison | −3686.06 | .02 | ||||||

| Late-onset vs Early-onset | −3247.51 | .02 | ||||||

Post-hoc Analyses

To clarify whether the associations between brain volumes and daily activity were unique to the limbic-associated structures in the prefrontal region or whether they extended to other regions of the frontal brain, associations between lateral prefrontal cortex and functioning were examined. The Bonferroni level of significance was set at α=.015. Gray and white matter volumes of the inferior, middle and superior frontal gyri were averaged and submitted to the same bivariate analyses used previously for predicting functional scales. (See Figure 2). Age and diagnosis alone were good fits for data from the three subscales (χ2 [df 4] = 14.1, p<.01 for Physical Function; χ2 [df 4] = 55.9, p<.01 for Energy; and χ2 [df 4] = 40.8, p<.01 for General Health). CIRS sympomatology, gray matter, white matter and all interactions were nonsignificant.

DISCUSSION

The first hypothesis was partially supported. Smaller volumes of white matter were associated with lower self-perceived Energy for depressed and non-depressed subjects. Smaller gray matter volumes were associated with lower self-perceived General Health for both diagnostic groups, and smaller white matter volumes trended toward significance for General Health. The association between gray matter volumes and General Health was particularly prominent for late-onset depressed patients, as anticipated. Contrary to expectations, Physical Function did not correlate with brain volumes although it trended toward a correlation with medical status.

Loss of energy is a common symptom of clinically-relevant depression40 and/or developing frailty.41,42 However, in this study, reduced volumes were related to decreased energy and/or increased fatigue for depressed and non-depressed participants. In the final regression equation, age, education, depression diagnosis, depression onset age and co-morbidity were all non-significant while white matter volume remained a significant predictor of self-perceived Energy. For otherwise healthy individuals, this finding suggests that early brain atrophic changes that are perceptible to the individual but are not yet linked to a clinical syndrome.

Self-reported perceptions of General Health showed multiple independent predictors, which is consistent with a multi-dimensional evaluation of general function. Education, depression diagnosis and gray matter volume, plus a trend from white matter volume, predicted perceived health. Of interest is the absence of age and concurrent morbidity as predictors of general health. This is consistent with Depp and Jeste’s (2006)10 review of successful aging studies in which elderly people considered absence of disability more significant to their lives than the presence of medical problems. In a series of focus group discussions, a majority felt a positive attitude, feeling of stability and security, health and wellness, and a source of engagement or continuing stimulation were more important than physical health.43 The group members expressed a view concurrent with a recent American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Conference on Frailty in Older Adults that defined frailty in medical terms as a spectrum of resilience that varies from highly independent to most frail.44 The concept is intrinsically independent from physiological disease, although they often develop concurrently,45 i.e., one can be highly robust yet have some physical disability or chronic condition.

If patients mention changes in their daily routines, they are likely to report them in vague terms, or not report them at all because they perceive them as normal for their age group or as appropriate for an accumulation of minor conditions. However, the process of aging affects the immune system by increasing circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, so when aging is combined with additional environmental stress, it takes a greater toll on an elderly adult than a young adult.46,47 Elderly people also find it more difficult to return to homeostasis. Even viral infections can result in elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression in the central nervous system similar to more serious physical or psychological stressors.48,49

A pronounced increase in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleuken 1, interleukin 6, tumor necropsy factor α) is associated with a nonspecific sickness syndrome that manifests with loss of appetite, withdrawal from normal social activities, anorexia, fatigue, increased pain, sleep disturbances and/or confusion.50 Current results suggest that some mechanism, possibly early pro-inflammatory cytokines, is associated with even minor volumetric changes and is perceived by elders as a decline in general health. Researchers have found preliminary evidence establishing a link between prolonged immune activation and the onset of depression51 and/or frailty.52 Elderly often deal with several major stressors that involve negative emotions such as care-giving, bereavement, relocating and loss of familiar neighborhoods, major medical events or problems with grown children that could precipitate slight increases in circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines. There are also indications that prenatal or early life stress may increase the likelihood of maladaptive immune responses to stress in late life.53

Another possible explanation is cerebrovascular disease, which is associated with increased hyperintense lesions on magnetic resonance imaging.54 Declines in daily functioning would not be tied directly to the presence of white matter hyperintensities, but rather indirectly through onset of depression and/or cognitive deficits.55,56 However, there were no differences across diagnostic groups in cardiovascular risk. Consequently, there is no obvious reason in terms of cerebrovascular disease why the late-onset depressed patients would perceive a stronger relationship between prefrontal brain volume and general health or energy levels than the other groups unless the late-onset group suffered significantly more hyperintensities without indication of this in their cardiovascular risk evaluation. If the diagnostic groups were equal in the amount of lesioned tissue, the amount of disruption caused by the hyperintense lesions would be the same for depressed patients and comparison individuals.57 Cerebrovascular disease would also affect the brain globally. This study showed that the OFC-anterior cingulate-gyrus rectus regions, but not non-limbic regions such as superior, middle and inferior frontal gyri, were associated with self-perceived energy and health, although both areas may be experiencing cerebrovascular changes.

Longitudinal research is needed that examines early stages of both sickness and frailty syndromes and accompanying biophysiologic and anatomic markers so that timely interventions can be suggested to patients before declines in functioning become clinically apparent. 58 Causality cannot be determined in this study, so the possibility must be considered that the brain differences reflect initial endowment in prefrontal volume. If brain volumes indicate hypodevelopment of prefrontal regions, they may potentiate exaggerated stress responses and decreased perceptions of health and well-being.

CONCLUSION

Linear associations exist between brain volumes and self-perceptions of energy and feelings of general health beyond that accounted for by depressive symptoms alone. White matter volumes were related to self-reported energy levels across all subjects, depressed and healthy. Both gray and white matter volumes contributed substantially to self-reports of overall general health for all subjects, although patients with late-onset depression have the strongest association. Consequently, the decreased functioning reported by depressed patients may be partially attributable to reduced volumes in prefrontal limbic-related structures rather than sequela to depressed mood. Relatively simple and straight-forward questions regarding patients’ perceptions of their health and energy level may provide insight into the patient’s overall functioning and open the discussion for more specific changes in elders’ lives.

Acknowledgments

Research grant support provided by National Institute of Mental Health KO2 MH02043 (Anand Kumar, PI); RO1 MH61567 (Anand Kumar, PI); MO1 RR00865 (General Clinical Research Center at UCLA)

Reference List

- 1.Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, et al. The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1796–1799. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mossey JM, Shapiro E. Self-rated health: a predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1982;72:800–808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.8.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramage-Morin PL. Successful aging in health care institutions. Health Rep. 2006;16(Suppl):47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergdahl E, Allard P, Lundman B, et al. Depression in the oldest old in urban and rural municipalities. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11:570–578. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van't Veer-Tazelaar PJ, Kostense PJ, van Oppen P, et al. Depression in old age (75+), the PIKO study. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:295–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kauppila T, Pesonen A, Tarkkila P, et al. Cognitive dysfunction and depression may decrease activities in daily life more strongly than pain in community-dwelling elderly adults living with persistent pain. Pain Pract. 2007;7:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2007.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, et al. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 1998;279:1720–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steffens DC, Hays JC, Krishnan KR. Disability in geriatric depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;7:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai SM, Duncan PW, Keighley J, et al. Depressive symptoms and independence in BADL and IADL. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39:589–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chodosh J, Kado DM, Seeman TE, et al. Depressive symptoms as a predictor of cognitive decline: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:406–415. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0b013e31802c0c63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnan KR, Delong M, Kraemer H, et al. Comorbidity of depression with other medical diseases in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:559–588. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Pieper CF. The association of depression and mortality in elderly persons: a case for multiple, independent pathways. J Gerontol, A Biol Sci, Med Sc. 2001;56:M505–M509. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.8.m505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hybels CF, Blazer DG. Epidemiology of late-life mental disorders. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19:663–696. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(03)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochsner KN, Beer JS, Robertson ER, et al. The neural correlates of direct and reflected selfknowledge. Neuroimage. 2005;28:797–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson SC, Baxter LC, Wilder LS, et al. Neural correlates of self-reflection. Brain. 2002;125:1808–1814. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogeley K, May M, Ritzl A, et al. Neural correlates of first-person perspective as one constituent of human self-consciousness. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:817–827. doi: 10.1162/089892904970799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson SC, Baxter LC, Wilder LS, et al. Neural correlates of self-reflection. Brain. 2002;125:1808–1814. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelley WM, Macrae CN, Wyland CL, et al. Finding the self? An event-related fMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:785–794. doi: 10.1162/08989290260138672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogeley K, May M, Ritzl A, et al. Neural correlates of first-person perspective as one constituent of human self-consciousness. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:817–827. doi: 10.1162/089892904970799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amaral DG, Price JL. Amygdalo-cortical projections in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis) J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:465–496. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbas H. Specialized elements of orbitofrontal cortex in primates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1121:10–32. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ongur D, Price JL. The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:206–219. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price JL. Definition of the orbital cortex in relation to specific connections with limbic and visceral structures, and other cortical regions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1121:54–71. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ballmaier M, Toga AW, Blanton RE, et al. Anterior cingulate, gyrus rectus, and orbitofrontal abnormalities in elderly depressed patients: An MRI-based parcellation of the prefrontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:99–108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ballmaier M, Kumar A, Thompson PM, et al. Localizing gray matter deficits in late-onset depression using computational cortical pattern matching methods. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2091–2099. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morecraft RJ, Geula C, Mesulam MM. Cytoarchitecture and neural afferents of orbitofrontal cortex in the brain of the monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1992;323:341–358. doi: 10.1002/cne.903230304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini Mental State": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton MA. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol, Neurosurg & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, et al. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linn BJ, Linn BW, Gurel L. Cumulative Illness Rating Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1968;16:622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDonald D, Avis D, Evans A. Multiple surface identification and matching in magnetic resonance images. In: Robb RA, editor. Proceedings of the SPIE Conference on Visualization in Biomedical Computing. Rochester, MN: Internat Soc Optical Engineering; 1994. pp. 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cirera L, Tormo MJ, Chirlaque MD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and educational attainment in Southern Spain: a study of a random sample of 3091 adults. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1023/a:1007596222217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Psaltopoulou T, Kyrozis A, Stathopoulos P, et al. Diet, physical activity and cognitive impairment among elders: the EPIC-Greece cohort (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) Public Health Nutr. 2008:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sachs-Ericsson N, Burns AB, Gordon KH, et al. Body mass index and depressive symptoms in older adults: the moderating roles of race, sex, and socioeconomic status. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:815–825. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180a725d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexopoulos GS. Depression in the elderly. Lancet. 2005;365:1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed N, Mandel R, Fain MJ. Frailty: an emerging geriatric syndrome. Am J Med. 2007;120:748–753. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Geriatric syndromes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:2092–2093. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichstadt J, Depp CA, Palinkas LA, et al. Building blocks of successful aging: a focus group study of older adults' perceived contributors to successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:194–201. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318030255f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walston JD, Fried LP. Frailty and its implications for care. In: Morrison RS, Meir DE, editors. Geriatric palliative care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:991–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graham JE, Christian LM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, age, and immune function: toward a lifespan approach. J Behav Med. 2006;29:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:873–876. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sudom KA, Hayley SP, Kelly OP, et al. Influence of chronic cytokine treatments: Neuroendocrine and anhedonic-like effects. Abst Soc Neurosci (#634 26) 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turrin NP, Plata-Salaman CR. Cytokine-cytokine interactions and the brain. Brain Res Bull. 2001;51:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dantzer R, Kelley KW. Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leng SX, Xue QL, Tian J, et al. Inflammation and frailty in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:864–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graham JE, Christian LM, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, age, and immune function: toward a lifespan approach. J Behav Med. 2006;29:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raz N, Rodrigue KM, Acker JD. Hypertension and the brain: Vulnerability of the prefrontal regions and executive functions. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1169–1180. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van den Heuvel DM, ten DV, de Craen AJ, et al. Increase in periventricular white matter hyperintensities parallels decline in mental processing speed in a non-demented elderly population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:149–153. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.070193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Videbech P. MRI findings in patients with affective disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1997;96:157–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor WD, Payne ME, Krishnan KR, et al. Evidence of white matter tract disruption in MRI hyperintensities. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peters KR, Rockwood K, Black SE, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptom clusters and functional disability in cognitively-impaired-not-demented individuals. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:136–144. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181462288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]