Abstract

Though tuberculosis (TB) primarily affects lungs, extra pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) is also common, especially in high disease load areas and mainly manifests in ENT region. To study the different manifestations of tuberculosis in ENT region in terms of presentation, disease process, treatment and outcome. Records of patients diagnosed and treated for TB in the ENT region at our institute’s DOTS centre for a two and half year period were analysed for presenting complaints, examination findings, diagnostic features, treatment modes and outcome. Out of 3750 cases diagnosed as TB, 230 had EPTB. 211 cases had ENT manifestations. Majority of the cases were male and in the fourth decade of life. Commonest manifestation was cervical lymphadenopathy with 201 cases. Fine needle aspiration cytology was mostly diagnostic and category I anti TB treatment (AKT) achieved cure. The six cases of TB otitis media presented with ear discharge, sometimes bloody and had varied tympanic membrane findings and facial palsy in two cases with different types and degrees of hearing loss. Diagnosis was confirmed by histology of tissue removed during surgery. Patients completed category I AKT. Hearing and facial palsy did not improve. There were three cases of TB laryngitis and one of nasal TB both of which were confirmed by tissue diagnosis and responded well to AKT. Most of the results in the present study conform to findings of other studies. High degree of suspicion is necessary to reach diagnosis. Category I AKT is effective. Some cases may require surgery.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Cervical lymphadenopathy, Tuberculous otitis media, Tuberculous laryngitis, Nasal tuberculosis

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) has been a bane for mankind since long. In spite of effective treatment regimen and governmental support it still takes a huge toll by mortality and morbidity especially in high disease load countries like India. Though lung is the commonest organ affected, no part of the body is immune.

Out of the many extra pulmonary manifestations of TB, a large proportion turns up in ear, nose and throat (ENT) region in the form of cervical lymphadenopathy, otitis media, laryngitis, pharyngitis and nasal TB [1]. Many times tuberculous affliction of atypical organs mimic other conditions and may delay diagnosis and worse still may lead to wrong treatment plans.

Hence it is mandatory in areas of high disease load like India that the medical practitioner should be aware of the extra pulmonary manifestations of TB, should be highly suspicious of the condition while managing patients, should confirm diagnosis by histopathology and institute proper treatment at the earliest.

Aim

To study the different manifestations of TB in ENT region in terms of presentation, disease process, treatment and outcome.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. Records of all patients registered at the DOTS (Direct Observed Treatment, Short Course) centre at our institute during the period January 2010 to June, 2012 were studied. All cases with TB in ENT region were considered for the study. Details regarding demographic data, presenting complaints, examination findings, investigation reports, treatment given and outcome were recorded. All data were collected, tabulated and analysed.

Results

A total of 3750 were diagnosed with TB in our institute during the period of review. Out of these 230 had extra pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) either in isolation or associated with concomitant pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB). Out of the 230 patients with EPTB, 211 cases had the manifestations of TB in the ENT region. These included patients with tuberculous cervical lymphadenopathy, laryngeal TB, tuberculous otitis media (TBOM) and nasal TB. 143 of these patients were male and the remaining female. The age distribution of the cases was as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age distribution

| Condition | 0–10 | 11–20 | 21–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | 61–70 | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | |

| Cervical lymphadenopathy | 2 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 31 | 14 | 56 | 23 | 31 | 16 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 201 |

| TB otitis media | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Laryngeal TB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Nasal TB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 3 | 16 | 48 | 83 | 47 | 12 | 2 | 211 | |||||||

Tuberculous Lymphadenopathy

By far the commonest EPTB manifestation in the study was tuberculous cervical lymphadenopathy accounting for 201 of the cases. There were 136 males and 65 females. The commonest age group affected was the fourth decade of life. The commonest presenting complaint was neck swelling (Fig. 1). There were other complaints like cough with expectoration (15 cases), fever (15 cases), and discharging sinus (6 cases). There were multiple lymph nodes in all but eight cases. Bilateral lymph node involvement was noted in 26 cases. In majority of the cases (176 cases) the posterior triangle lymph nodes were involved. The next common group of lymph nodes involved were the anterior triangle, middle third group. Axillary lymph nodes were involved in 12 cases. All the patients were sent for fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). 193 cases had their diagnosis confirmed by this investigation itself. Conclusive diagnosis could not be arrived in eight cases. These cases were confirmed by a surgical excision biopsy. Fifteen patients had PTB too. Two patients were also seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV positive) (Fig. 2). The patients were started on category I anti tuberculous treatment (AKT) according to Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP). They were kept on monthly follow up till the completion of treatment and as per requirements after that. Patients who were HIV positive were also given anti retroviral therapy according to CD4 counts. In 195 of the cases the swelling subsided by the end of the treatment course. In five patients the swelling remained of same size in spite of taking full treatment and in one case it had actually increased in size. Four of the patients opted for surgical excision of the nodes. There was no evidence of TB in the nodes.

Fig. 1.

Patient of cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy

Fig. 2.

HIV positive patient with cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy showing multiple lymph node group involvement

Tuberculous Otitis Media

There were six cases of TBOM. These cases were distributed equally between males and females and in the three age groups: 21–30, 31–40 and 41–50. Ear discharge was the presenting chief complaint in all cases. There were other complaints like hearing loss (five cases), ear ache (one case) and facial weakness (two cases). Tympanic membrane perforation was present in all cases. However multiple perforations were present in only one case. There was a polyp in one case and granulations on the tympanic membrane in four cases. Two cases had ipsilateral lower motor neurone type of facial palsy. Pure tone audiometry revealed pure conductive loss of the order of 40 dB in one case. There was mixed hearing loss in all the remaining cases. Mean bone conduction threshold of all cases was 43.3 dB and mean air-bone gap was 15.6 dB. One case also had PTB which was revealed on X ray chest.

All cases underwent mastoidectomy and tympanoplasty. Polyps and granulations removed during surgery were sent for histopathological examination (HPE) which revealed the diagnosis of TB. Patients were started on category I AKT together with routine post operative care. Patients were kept on monthly follow up till completion of AKT and as and when required after that. The last follow up of all patients revealed a well healed mastoid cavity and sputum negative for acid fast bacilli in all cases. However there was not much improvement in the audiological profile of the cases, with post operative mean bone conduction threshold of 41.2 dB and mean air-bone gap of 21.6 dB. Facial nerve palsy also did not recover after surgery or AKT.

Tuberculous Laryngitis

There were three cases of tuberculous laryngitis. All these case also had PTB. All cases were male and above 50 years of age. They had presenting complaints of hoarseness together with complaints of cough with expectoration and fever. In two cases hoarseness developed 1–3 months after the complaints of cough with expectoration. In one case both complaints were reported to have developed together. Sputum for AFB was positive in all cases. One patient was seropositive for HIV. A direct laryngoscopy was done to rule out malignancy. There was marked congestion of the laryngeal mucosa in all cases. There was polypoidal mucosa over the laryngeal parts which were stripped as much as possible. There was no evidence of any mass or vocal cord palsy. Histopathology of the stripped material revealed the etiology as tuberculosis. Category I AKT was started as per RNTCP guidelines. Patient was followed up uneventfully monthly till the end of treatment. Whereas two of the patients regained their normal voice, one patient had persistent hoarseness even after successful completion of treatment.

Nasal Tuberculosis

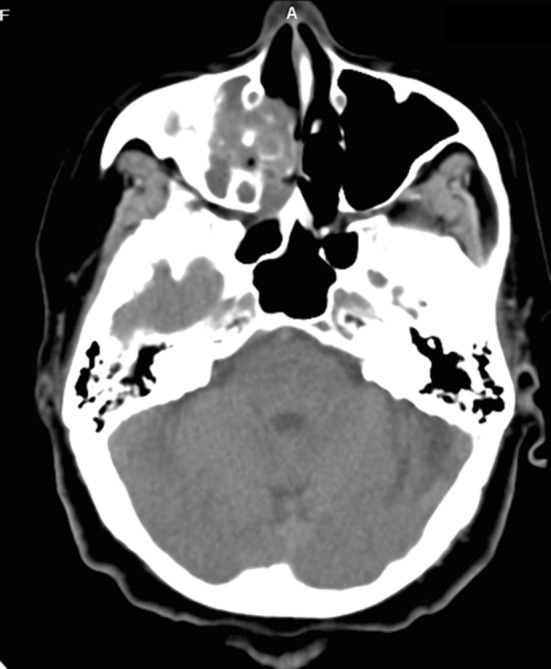

There was one case of nasal TB during the period of review. Patient was a 23 year old female who presented to us with right sided nasal obstruction and occasional blood stained nasal discharge for 3 months. Examination revealed a pale polypoidal mass filling up the right nasal cavity. There was no apparent external nasal deformity. Computerised tomography of the paranasal sinuses showed a mass in the nasal cavity and extending to the anterior paranasal sinuses, abutting but not eroding the nasal septum (Fig. 3). Patient was taken up for endoscopic sinus surgery. The whole polypoidal mass was removed piecemeal and sent for HPE which turned up a report of TB. Patient was started on category I AKT and at the time of writing this article has finished 5 months of treatment.

Fig. 3.

CT scan of paranasal sinus of patient of nasal tuberculosis

Discussion

Out of the total 3750 cases of TB reviewed during the period of the study there were 230 cases of EPTB. This 6.1 % incidence of EPTB is much lower than the 15–40 % reported in literature [2–5]. This could be because of the high disease load which primarily manifests as PTB. The male predominance in our study group (143/211) and very low proportion of cases with immunocompromise (3/211) is contrary to the findings of Mazza-Stalder et al. [2], Stelianides et al. [4]. However these studies were from low disease load, developed countries. Studies done in India have reported a clear cut male preponderance [6]. The age distribution shows a normal pattern with a peak of 38.4 % in the fourth decade of life. This is as per the distribution reported by Chakravarty et al. [1, 6]. It has been reported that usually PTB is not associated with EPTB. However in the present study 9 % of the cases had active PTB too. Incidence of ENT manifestations of EPTB has been reported as low as 5 % [1]. This is contrary to our findings wherein majority of the EPTB cases (91.7 %) were in the ENT region.

TB lymphadenitis of the cervical region is the commonest manifestation of EPTB [2, 4, 6–8]. In the present study too cervical TB lymphadenitis accounted for 87.4 % of cases of EPTB and 95.3 % of cases of EPTB in the ENT region. In the present study the pattern of lymph node involvement showed multiple lymph node group involvement in 96.5 % of the cases and the commonest lymph node group involved was of the posterior triangle (88 %). This corresponds to the findings in other studies [7]. Most of the times FNAC clinches the diagnosis as was the case in the present study (96.5 %) [6, 7]. However in eight cases surgical excision biopsy was needed to confirm the diagnosis. It has been suggested by Chakravorty et al. [6] that the paucibacillary nature of tissue other than sputum compromises the diagnosis rate in TB. Two of the patients (1 %) were HIV positive and these cases also had PTB. HIV positive patients are known to have more incidence of multiple site involvement. The incidence of HIV positivity in patients with TB lymphadenitis has been reported around 8 % [9]. The cornerstone of management of TB lymphadenopathy is AKT which has proven very effective in the management in all studies [7]. However in certain situations there is limited role of surgery too [9].

TBOM is one of the rare manifestations of TB [10]. It accounted for 0.1 % of all TB cases and 1.7 % of EPTB case in the present study. Though the classical description of TBOM has been multiple tympanic membrane perforations in a patient with painless ear discharge and disproportionate sensorineural hearing loss, various studies have reported a whole range of ear findings and different types and severity of hearing loss [10–13]. In the present study too there were a variety of ear findings including perforations, granulations and polyps. The classical multiple perforations were noted in 1 cases only. TBOM has also been known to be associated with PTB up to 32 % [10, 11] and it was so in 1 case (25 %) in our study. Incidence of facial palsy in TBOM has been reported in contemporary literature to be up to 35 % [12] and recovery even after successful treatment has been variable. There was a 50 % incidence in the present study with no recovery even after surgery. HPE of diseased tissue from the ear is the surest way to confirm the diagnosis of TBOM. Detection rates of AFB has been reported to be in the order of 5–35 % which at best can get to 50 % with repeated testing [11–14]. AKT with or many times without surgery can cure TBOM effectively [11–14]. All our cases also had complete cure with category I AKT. However improvement in hearing was very marginal. This has also been reported by other studies [10, 12].

Dysphonia is the commonest presenting complaint with pain also being a prominent feature in laryngeal TB [1, 15–18]. Though all our patients complained of hoarseness, pain was not a chief complaint. All our patients also had PTB. This is as per reports in literature wherein it has been reported that 1 % of cases of PTB have LTB and 100 % of cases of LTB have PTB [17–21]. It is believed that the recent resurgence in reported cases of LTB is due to increase in HIV cases [15, 17, 18]. There was one case in our study too (33.3 %). A direct laryngoscopy is necessary not only to confirm diagnosis and rule out malignancy but also to take tissue for HPE [15, 16, 18]. Besides the patient features (smokers) and presenting complaints (dysphonia and pain) suggesting carcinoma in patients of laryngeal TB, even the histology may mimic carcinoma due to epithelial hyperplasia [15, 17–19]. Though it has been reported that hoarseness usually responds to AKT, the fibrotic healing of the tuberculous lesions may lead to long term compromise of voice. Again AKT has proven to be effective; but surgery may be required in cases of airway compromise due to active disease process or scarring in cured cases [15, 16, 19].

Nasal TB is a very rare entity even in countries with high disease load [22]. We had only one case over a period of two and half years. There is a clear preponderance of females in all reported literature though no reasons have been ascribed for it. Mean age in the case series by Kim et al. [22, 23] was 31 years. But cases as old as 89 years have been reported. Our patient was a 23 year old female. Reports of concomitant PTB range from 0 to over 75 %. This wide range is due to the very less numbers in different case series [5, 22, 23]. The complaint of bloody nasal discharge reported by our case was also noted by Dixit et al. [22] in their case report. The case in the present study had nasal mass with sinus involvement. Such a pattern of involvement has been reported by other studies too [5, 20, 22, 23]. However the commonest feature of nasal tuberculosis is septal involvement with perforation resulting in external nasal deformity. A high index of suspicion is the only key especially since there can be varied differential diagnosis [22, 23]. AKT has been reported to be sufficiently effective in achieving complete cure [5, 22, 23].

Conclusion

Extra pulmonary tuberculosis especially in high disease load countries like India is not a very rare phenomenon. The ENT region is one of the commonest areas of affliction by extra pulmonary TB. Only a high index of suspicion with proper tissue diagnosis can detect these cases. Patients usually respond well to the recommended category I AKT. Surgery may be required in some cases.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.de Sousa RT, Briglia MFS, de Lima LCN, de Carvalho RS, Teixeira ML, Marcião AHR. Frequency of Otorhinolaryngologies’manifestations in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;14(2):156–162. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazza-Stalder J, Nicod L, Janssens JP. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Rev Mal Respir. 2012;29(4):566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.rmr.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Roux P, Quinque K, Bonnel AS, Le Luyer B. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in childhood. Arch Pediatr. 2005;12(Suppl 2):S122–S126. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(05)80027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stelianides S, Belmatoug N, Fantin B. Manifestations and diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Rev Mal Respir. 1997;14(Suppl 5):S72–S87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hup AK, Haitjema T, de Kuijper G. Primary nasal tuberculosis. Rhinology. 2001;39:47–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakravorty S, Sen MK, Tyagi JS. Diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by smear, culture, and PCR using universal sample processing technology. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(9):4357–4362. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4357-4362.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayazit YA, Bayazit N, Namiduru M. Mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2004;66(5):275–280. doi: 10.1159/000081125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinho MM, Kós AOA. Otite Média Tuberculosa, Artigo deRevisão. Rev Bras Otorrinol. 2003;68(5):829–837. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohan A, Reddy KM, Phaneendra BV, Chandra A. Aetiology of peripheral lymphadenopathy in adults: analysis of 1724 cases seen at a tertiary care teaching hospital in southern India. Natl Med J India. 2007;20(2):78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abes GT, Abes FL, Jamir JC. The variable clinical presentation of tuberculosis otitis media and the importance of early detection. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(4):539–543. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182117782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaniv E. Tuberculous otitis: an underdiagnosed disease. Am J Otolaryngol. 1987;8(6):356–360. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(87)80020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adhikari P. Tuberculous otitis media: a review of literature. Internet J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;9(1):7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaniv E, Traub P, Conradie R. Middle ear tuberculosis–a series of 24 patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1986;12(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(86)80058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirsch CM, Wehner JH, Jensen WA, Kagawa FT, Campagna AC. Tuberculous otitis media. South Med J. 1995;88(3):363–366. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199503000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yencha MW, Linfesty R, Blackmon A. Laryngeal tuberculosis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21(2):122–126. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(00)85010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Essaadi M, Raji A, Detsouli M, Mokrim B, Kadiri F, Laraqui NZ, et al. Laryngeal tuberculosis: apropos of 15 cases. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2001;122(2):125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levenson MJ, Ingerman M, Grimes C, Robbett WF. Laryngeal tuberculosis: review of twenty cases. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(8):1094–1097. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198408000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pino Rivero V, Marcos García M, González Palomino A, Trinidad Ruiz G, Pardo Romero G, Pimentel Leo JJ, Blasco Huelva A (2005) Laryngeal tuberculosis masquerading as carcinoma. Report of one case and literature review. An Otorrinolaringol Ibero Am 32(1):47–53 [PubMed]

- 19.de Bree R, Chung RP, van Aken J, van den Brekel MW. Tuberculosis of the larynx. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1998;142(29):1676–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galietti F, et al. Examination of 41 cases of laryngeal tuberculosis observed between 1975–1985. Eur Respir J. 1989;2(8):731–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Windle-Taylor P, Bailey CM. Tuberculous otitis media: a series of 22 patients. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:1039–1044. doi: 10.1002/lary.1980.90.6.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixit R, Dave L. Primary nasal tuberculosis. Lung India. 2008;25:102–103. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.44127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YM, Kim AY, Park YH, Kim DH, Rha KS. Eight cases of nasal tuberculosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3):500–504. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]