Abstract

Background

Many studies have assessed perspectives of medical students toward institutional diversity, but few of them have attempted to map changes in diversity climate over time.

Objective

This study aims to investigate changes in diversity climate at a Jesuit medical institution over a 12-year period.

Methods

In 1999, 334 medical students completed an anonymous self-administered online survey, and 12 years later, 406 students completed a comparable survey in 2011. Chi-square tests assessed the differences in percent responses to questions of the two surveys, related to three identities: gender, race, and sexual orientation.

Results

The 1999 versus 2011 samples were 46% versus 49% female, 61% versus 61% Caucasian, and 41% vs. 39% aged 25 years or older. Findings suggested improvements in medical students’ perceptions surrounding equality ‘in general’ across the three identities (p<0.001); ‘in the practice of medicine’ based on gender (p<0.001), race/ethnicity (p=0.60), and sexual orientation (p=0.43); as well as in the medical school curriculum, including course text content, professor’s delivery and student–faculty interaction (p<0.001) across the three identities. There was a statistically significant decrease in experienced or witnessed events related to gender bias (p<0.001) from 1999 to 2011; however, reported events of bias based on race/ethnicity (p=0.69) and sexual orientation (p=0.58) only showed small decreases.

Conclusions

It may be postulated that the improvement in students’ self-perceptions of equality and diversity over the past 12 years may have been influenced by a generational acceptance of cultural diversity and, the inclusion of diversity training courses within the medical curriculum. Diversity training related to race and sexual orientation should be expanded, including a follow-up survey to assess the effectiveness of any intervention.

Keywords: medical students, diversity, curriculum, equality, survey, identity

Introduction

The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) defines an appropriate institutional setting for medical education as an ‘environment characterized by, and supportive of, diversity and inclusion’ (1). Diversity training in medical education is not only essential for academic excellence during medical training, but has also shown to provide far-reaching benefits later on in medical practice, including health disparity reduction, better physician–patient interaction, as well as enhanced patient adherence, satisfaction, and clinical outcomes (2, 3).

Institutional leadership can help define this essential atmosphere of cultural competency with ‘creation of curricula and environments’ that supports critical dialogue on the potentially contentious issues of gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation (4). Therefore, it is important to assess cultural climate related to diversity at medical schools for augmentation and benchmarking the system (5).

There have been many studies gauging perceptions and attitudes of medical students toward diversity and cultural competency, with or without interventions (6–9). Very few longitudinal studies have attempted to map changes in cultural climate and institutional discourse on diversity over time. A longitudinal qualitative study evaluating gendered encounters in medical education revealed that third-year female medical students easily acclimatized to inappropriate behavior from male patients, but not toward unprofessional behavior of male supervisors (10). Another study with a 4-year follow-up survey administered to 185 lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) medical students across 92 medical schools in the United States, found that LGB medical students’ needs were being increasingly met, but student–faculty liaisons and more support groups were needed; LGB medical students also felt there was a paucity of exposure to non-pejorative descriptions of LGB patients, and a need for LGB patient care being taught more widely (11).

To the best of our knowledge, this article documents the first longitudinal study assessing changes in diversity climate at a Jesuit medical institution, which espouses cultural competency through its teaching of Cura Personalis, an Ignatian principle adapted for healthcare. Translated as ‘care of the whole person’, Cura Personalis advocates individualized attention to other’s needs, ‘distinct respect for unique circumstances’, and a suitable appreciation for ‘singular gifts and insights’ (12). The study compares students’ responses to surveys related to gender, race, and sexual orientation-based diversity and bias, which were conducted in 1999 and again in 2011.

Methods

Participants

In 1999, 334 first- and second-year medical and post-baccalaureate physiology graduate students at a private, Jesuit medical school in the US completed an anonymous self-administered online survey. Twelve years later, 406 first- and second-year medical and post-baccalaureate physiology graduate students completed a comparable survey from January to April, 2011.

Data collection

The two cohorts were compared, estimating the differences in percent responses to questions of the two surveys. The study focused on responses to matching questions in both surveys on gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation-based equality (Table 1) related to: 1) level of importance attributed to equality in general; 2) perceptions of equality in the practice of medicine; 3) students’ assessment of equality based on gender, race, and sexual orientation in the curriculum; and 4) witnessing or experiencing gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation bias.

Table 1.

Survey questions in both 1999 and 2011 studies

| Theme | Question | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Importance of equality in general | 1) How important is it to you that men and women are treated equally? 2) How important is to you that people of different races/ethnicities are treated equally? 3) How important is to you that people of different sexual orientations are treated equally? |

Not at all, Slightly, Moderately, A lot, Extremely |

| Equality in the practice of medicine | 4) Do you believe women and men are treated equally in the practice of medicine? 5) Do you believe people of different race/ethnicity are treated equally in the practice of medicine? 6) Do you believe people with different sexual orientations are treated equally in the practice of medicine? |

Yes, No |

| Equality in medical curriculum | 7) At the medical school, do you believe that men and women are treated equally in: 1) Course texts; 2) Professor’s delivery; 3) Student–Faculty interaction? 8) At the medical school, do you believe that people of different race/ethnicity are treated equally in: 1) Course texts; 2) Professor’s delivery; 3) Student–Faculty interaction? 9) At the medical school, do you believe that people with different sexual orientations are treated equally in: 1) Course texts; 2) Professor’s delivery; 3) Student–Faculty interaction? |

Yes, No |

| Witnessing or experiencing bias at the medical school | 10) Have you personally witnessed or experienced bias based on gender at the medical school? 11) Have you personally witnessed or experienced bias based on race/ethnicity at the medical school? 12) Have you personally witnessed or experienced bias based on sexual orientation at the medical school? |

Yes, No |

Data analysis

For each identity, we calculated the percentage of respondents choosing each category and estimated differences between the percent responses for 1999 and 2011. Chi-square tests assessed whether there were any significant differences in the responses between the two survey years. Statistical significance was evaluated at the 0.05 level. The data were analyzed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., USA).

Results

The 1999 vs. 2011 sample demographic compositions were as follows: 46% (153/334) vs. 49% (199/406) female, 61% (204/334) vs. 61% (247/406) Caucasian, and 41% (137/334) vs. 38% (156/406) were older than 25 years. The two samples were not significantly different with respect to gender, age, student status, and race (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic data for medical students participating in the 1999 and 2011 studies

| Variable | Study 1999 (N=334) n (%) |

Study 2011 (N=406) n (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.198 | ||

| Male | 178 (53.3) | 207 (51.0) | |

| Female | 153 (45.8) | 199 (49.0) | |

| Missing data | 3 (0.9) | 0 | |

| Age | 0.094 | ||

| ≤22 years | 50 (15.0) | 46 (11.3) | |

| 23–24 years | 147 (44.0) | 204 (50.2) | |

| 25–26 years | 74 (22.1) | 99 (24.4) | |

| 27–29 years | 41 (12.3) | 43 (10.6) | |

| ≥30 years | 22 (6.6) | 14 (3.5) | |

| Student status | 0.281 | ||

| 1st Year | 123 (36.8) | 158 (38.9) | |

| 2nd Year | 137 (41.0) | 139 (34.2) | |

| GEMS | 11 (3.3) | 17 (4.2) | |

| Grads | 63 (18.9) | 90 (22.2) | |

| Missing data | 0 | 2 (0.5) | |

| Race | 0.381 | ||

| Black | 25 (7.5) | 25 (6.2) | |

| Asian | 60 (18.0) | 81 (20.0) | |

| White | 204 (61.1) | 247 (60.8) | |

| Latino | 14 (4.1) | 17 (4.1) | |

| Indian | 14 (4.2) | 10 (2.5) | |

| Middle Eastern | 5 (1.5) | 15 (3.7) | |

| Native American | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Missing data | 10 (3.0) | 10 (2.5) |

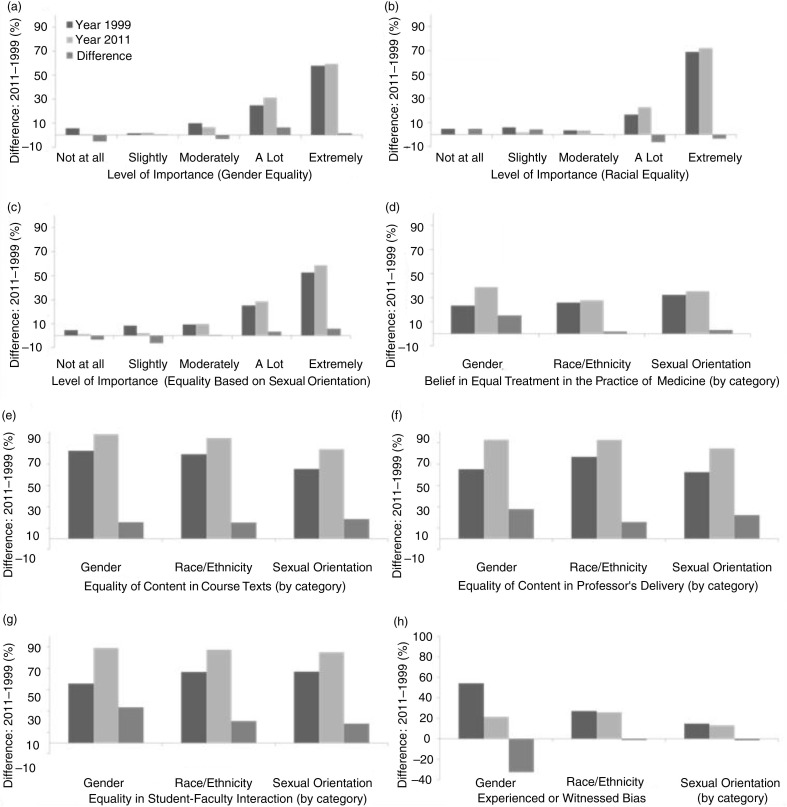

Students in the 2011 survey, as compared to students in the 1999 survey, placed significantly greater value on the importance of equality in general based on gender (24.8% vs. 31.3% gave ‘a lot’ of importance, p<0.001); race/ethnicity (16.7% vs. 23% gave ‘a lot’ of importance, p<0.001); and sexual orientation (52.5% vs. 58.4% responded ‘extremely’ important, p <0.001) (Fig. 1a–c).

Fig. 1.

Response comparisons between the 1999 and 2011 surveys.

Students in 2011 were more likely than students in 1999 to ‘believe in equality in the practice of medicine’, based on gender (15.3%, p<0.001), race (1.8%, p=0.60), and sexual orientation (3.1%, p=0.43), with gender equality demonstrating a statistically significant improvement (Fig. 1d).

Researchers noted a positive increase from 1999 to 2011 in the students’ perception of equality based on gender, race, and sexual orientation at the medical school in course text content, professor’s delivery and student–faculty interaction (p<0.001); gender equality in student–faculty interaction and professor’s delivery demonstrated the greatest positive increase of 33.5 and 27.9%, respectively (Fig. 1e–g).

There was a statistically significant decrease in experienced or witnessed events related to gender bias (54.2% vs. 21.4%, p<0.001) from 1999 to 2011 (Fig. 1f); however, reported events of bias based on race/ethnicity (27.2% vs. 25.9%, p=0.69) and sexual orientation (14.6% vs. 13.2%, p=0.58) only showed small decreases that were not statistically significant (Fig. 1f).

Discussion

We found improvements in medical students’ perceptions surrounding equality in general, in the practice of medicine, and in the medical curriculum. We also found improvement in the decreasing percentage of students who have witnessed or experienced negative bias based on gender, race/ethnicity and sexual orientation, albeit those for race/ethnicity and sexual orientation were not statistically significant.

In this study, students’ perceptions and attitudes toward gender equality showed a substantial positive increase, reflecting the shift in focus of gender issues in academic medicine from mitigating discrimination and sexual harassment (SH) to facilitating an environment conducive for excellence in medicine. Three previous questionnaire-based studies demonstrated that gender-based discrimination (GD) and SH were prevalent in undergraduate medical education as well as among medical school faculty (13–15). A 2013 study measuring the key aspects of academic medicine culture noted that though male and female medical academicians were equally engaged in their work and had similar professional aspirations, medical institutions have failed to provide an environment supporting and accepting of women in medicine (14). Another recent study surveyed 4,578 full-time faculty from 26 representative US medical schools and noted that gender was not predictive of intentions for leaving academic medicine (15). Looking at perspectives in society-at-large, a 2013 Gallup poll indicated that 85% of women did not perceive gender bias in promotions at work (16). The current study and others would support the fact that, gender biases, do still exist within the faculty of the biological and physical sciences, but on a more subtle level (17).

US national-level surveys indicate that small shifts in attitudes and perspectives on racial equality have occurred over the past decade, reflecting results of our study. A 2013 Pew Research survey, assessing diversity and inclusion within society-at-large, indicated that 35% of Blacks, 20% of Hispanics, and 10% of Whites say that they have experienced discrimination because of their race and ethnicity over the past year (18). Moreover, the Pew survey noted that ‘while 45% of Americans say the country has made ‘a lot’ of progress in the past 50 years toward racial equality, about half the American public says ‘a lot’ more needs to be done’.

For changes in diversity regarding sexual orientation, a 2013 Pew survey indicated that 92% of America’s LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender) adults say ‘society has become more accepting of them in the past decade’ and an equal number expect it to ‘grow even more accepting in the decade ahead’ (19). While the acceptance of homosexuality over the past decade increased from 40% in 2001 to 56% in 2011 (20), 63% of Americans describe discrimination based on sexual orientation as a serious problem (21). Our results showed only a 1.4% decrease in self-reported events of ever witnessing or experiencing negative bias based sexual orientation at the medical school over the past decade, even though Washington, DC has the highest LGBT percentage in the United States (22). This demonstrates the prevalence of how implicit, or unconscious, biases against certain groups can influence behavior, even when measures of explicit beliefs show no group biases (23–25).

An online survey administered nationally to 427 LGBT physicians revealed that LGBT educational content has not been sufficiently included in formal medical school curriculum to bring about an alteration in the ‘heterosexist and gender normative practices’ in medical practice (26). Moreover, there seems to be a paucity of cross-cultural medical training during clinical rotations in the United States (2). Another study evaluating sexuality education focused on North American medical students, noted that education material on sexual minority groups is scant or absent in most curriculum (27). Meanwhile, a university in California assessed the impact of an LGBT health curriculum on second-year medical students by administering matched questionnaires eliciting knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of students about LGBT health issues before and after completion of the course. The study demonstrated that a ‘simple curricular intervention’ could produce significant short-term changes in a small number of survey items (7). Sustaining those changes may require a longer-term plan.

While our results indicate positive changes in student perspectives on equality based on gender, race, and sexual orientation, they could possibly be explained by the shifting societal perspectives on gender and racial equality. Our results could also be the result of a concerted effort by the medical school. Guided by the Jesuit core value of Cura Personalis, to create and increase a diverse medical school environment, the Medical School Executive Faculty updated the school of medicine diversity statement:

The University was founded on the principle that serious and sustained discourse among people of different faiths, cultures and beliefs promotes intellectual, ethical and spiritual understanding. Consistent with this principle, the School of Medicine strives to ensure that its students become respectful physicians who embrace all dimensions of diversity in a learning environment that understands and includes the varied health care needs and growing diversity of the populations we serve. (28)

In keeping with this stated mission, the School of Medicine has implemented outreach programs in order to facilitate the diversity of the student body. In addition, our university has initiated periodic campus-wide initiatives to promote a respectful campus community to increase an environment of anti-harassment, promote diversity and equality, and raise awareness of diversity issues on campus. These efforts have been combined with an integration of diversity topics into the curriculum to provide students with the tools required to practice healthcare in an increasingly diverse healthcare arena.

Our study was limited to assessing pre-clinical education only and therefore cannot be extrapolated to clerkship rotations where a higher prevalence of bias may be expected due to increased clinician–student–patient interactions. Moreover, any underreporting of responses to these sensitive questions would underestimate any differences particularly among those who are highly vulnerable to experiencing or witnessing bias.

We postulate that the improvement in students’ self-perceptions of equality and diversity at the medical school over the past 12 years may have been influenced by two primary factors: 1) a generational acceptance of cultural diversity as reflected in the society-at-large facilitated by the use of the Internet and social networks; and 2) the inclusion of diversity training and health disparities courses within the medical curriculum. Diversity training related to race and sexual orientation should be expanded, including a follow-up survey to assess the effectiveness of any intervention.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dean Stephen Ray Mitchell, Georgetown University School of Medicine, for funding the 2011 survey and Dr. Ying Li for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interest and funding

This project was funded by the Georgetown University School of Medicine. There was no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board, Washington, DC, United States.

References

- 1.Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) Institutional settings IS-16. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH23pPAr) [cited 25 July 2013]

- 2.Kripalani S, Bussey-Jones J, Katz MG, Genao I. A prescription for cultural competence in medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1116–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nivet MA. Commentary: Diversity 3.0: a necessary systems upgrade. Acad Med. 2011;86:1487–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182351f79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tervalon M. Components of culture in health for medical students’ education. Acad Med. 2003;78:570–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milem JF, Dey EL, White CB. Contribution D: diversity considerations in health professions education. In: Butler AS, Bristow LR, Smedley BD, editors. In the nation’s compelling interest: ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 345–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hung R, McClendon J, Henderson A, Evans Y, Colquitt R, Saha S. Student perspectives on diversity and the cultural climate at a U.S. medical school. Acad Med. 2007;82:184–92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d936a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelley L, Chou CL, Dibble SL, Robertson PA. A critical intervention in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: knowledge and attitude outcomes among second-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20:248–53. doi: 10.1080/10401330802199567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhaliwal JS, Crane LA, Valley MA, Lowenstein SR. Student perspectives on the diversity climate at a U.S. medical school: the need for a broader definition of diversity. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:154. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elam CL, Johnson MM, Wiggs JS, Messmer JM, Brown PI, Hinkley R. Diversity in medical school: perceptions of first-year students at four southeastern U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2001;76:60–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200101000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babaria P, Abedin S, Berg D, Nunez-Smith M. “I’m too used to it”: a longitudinal qualitative study of third year female medical students’ experiences of gendered encounters in medical education. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townsend MH, Wallick MM, Cambre KM. Follow-up survey of support services for lesbian, gay, and bisexual medical students. Acad Med. 1996;71:1012–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199609000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgetown University School of Medicine Committee on Medical Education. What is Cura Personalis. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH1R1NNg) [cited 15 December 2012]

- 13.Nora LM, McLaughlin MA, Fosson SE, Stratton TD, Murphy-Spencer A, Fincher RM, et al. Gender discrimination and sexual harassment in medical education: perspectives gained by a 14-school study. Acad Med. 2002;77:1226–34. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200212000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pololi LH, Civian JT, Brennan RT, Dottolo AL, Krupat E. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:201–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pololi LH, Krupat E, Civian JT, Ash AS, Brennan RT. Why are a quarter of faculty considering leaving academic medicine? A study of their perceptions of institutional culture and intentions to leave at 26 representative U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2012;87:859–69. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182582b18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendes E. In U.S., 15% of women feel unfairly denied a promotion. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH2FL86h) [cited 26 August 2013]

- 17.Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pew Research Center. King’s dream remains an elusive goal; many Americans see racial disparities. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH2IyBEL) [cited 26 August 2013]

- 19.Pew Research Center. A Survey of LGBT Americans: attitudes, experiences and values in changing times. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH2LdPSy) [cited 26 August 2013]

- 20.Gallup. Gay and Lesbian rights. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH1cqTOW) [cited 13 September 2013]

- 21.Jones JM. Most in U.S. say Gay/Lesbian Bias is a serious problem. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH1w6jxX) [cited 4 September 2013]

- 22.Gates GJ, Newport F. LGBT percentage highest in D.C., lowest in North Dakota. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH1hg6R5) [cited 26 August 2013]

- 23.Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol Rev. 1995;102:4–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nosek BA, Smyth FL. A multitrait–multimethod validation of the Implicit Association Test: implicit and explicit attitudes are related but distinct constructs. Exp Psychol. 2007;54:14–29. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169.54.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nosek BA, Hawkins CB, Frazier RS. Implicit social cognition: from measures to mechanisms. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eliason MJ, Dibble SL, Robertson PA. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) physicians’ experiences in the workplace. J Homosex. 2011;58:1355–71. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.614902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shindel AW, Parish SJ. Sexuality education in North American medical schools: current status and future directions. J Sex Med. 2013;10:3–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02987.x. quiz 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georgetown University School of Medicine Committee on Medical Education. Georgetown University School of Medicine Mission and Diversity Statement. Available from: (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6LH1YEXco) [cited 30 September 2013]