Abstract

Induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes (iPS-CMs) might become therapeutically relevant to regenerate myocardial damage. Purified iPS-CMs exhibit poor functional integration into myocardial tissue. The aim of this study was to investigate whether murine mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) or their conditioned medium (MScond) improves the integration of murine iPS-CMs into myocardial tissue. Vital or nonvital embryonic murine ventricular tissue slices were cocultured with purified clusters of iPS-CMs in combination with murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), MSCs, or MScond. Morphological integration was assessed by visual scoring and functional integration by isometric force and field potential measurements. We observed a moderate morphological integration of iPS-CM clusters into vital, but a poor integration into nonvital, slices. MEFs and MSCs but not MScond improved morphological integration of CMs into nonvital slices and enabled purified iPS-CMs to confer force. Coculture of vital slices with iPS-CMs and MEFs or MSCs resulted in an improved electrical integration. A comparable improvement of electrical coupling was achieved with the cell-free MScond, indicating that soluble factors secreted by MSCs were involved in electrical coupling. We conclude that cells such as MSCs support the engraftment and adhesion of CMs, and confer force to noncontractile tissue. Furthermore, soluble factors secreted by MSCs mediate electrical coupling of purified iPS-CM clusters to myocardial tissue. These data suggest that MSCs may increase the functional engraftment and therapeutic efficacy of transplanted iPS-CMs into infarcted myocardium.

Introduction

Proof-of-principle studies demonstrated that transplanted cardiomyocytes (CMs) can engraft into the injured ventricular wall, and can restore the electrical and mechanical function of the ischemically injured heart [1–3].

Currently, cardiac progenitor cells [4] and CMs derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSs) [5,6] represent the most promising source of CMs for cardiac regenerative medicine. However, transplantation of these CMs seems to be more difficult than using neonatal CMs [7,8] because of their poor engraftment and limited survival after transplantation. One reason for this might be that neonatal CMs used in the proof-of-principle studies mentioned earlier used dissociated myocardium, that is, a mixture of CMs and other cardiac cell types, such as fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and possibly multipotent cardiac progenitor cells. In contrast, CMs derived from embryonic stem (ES) and iPS cells have to be purified to avoid tumor formation [9,10], and are therefore transplanted in the absence of other cell types. Previously, we have shown that purified ES-cell-derived CMs (ES-CMs) have very selective requirements for adherence to different substrates in vitro and are unable to form homotypic intercellular interactions efficiently. This may emphasize their poor in vivo engraftment capability [11]. Additionally, our group reported that in vitro cotransplantation of murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) enabled purified ES-CMs to integrate and confer force of contraction to nonvital myocardial tissue [12]. These results provided evidence that functional integration into nonvital myocardial tissue and cellular engraftment requires factors that most likely can only be provided by vital cells. In vivo infarct models are often too complex to allow meaningful conclusions, especially on mechanisms of cell integration. Technical limitations largely preclude repetitive measurements or pharmacological testing in vivo [13–15]. Therefore, we used an in vitro tissue culture model to mimic cardiac cell therapy [16]. Our earlier observations suggested that nonpurified human ES-CMs [17] integrate better than purified murine ES-CMs into nonvital heart slices. This points again toward a demand for supporting cells in order to optimize engraftment of CMs. Other potential mediators for an improved integration are mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which with their known potential to induce angiogenesis affect cellular migration and inhibit apoptosis [18]. Intravenously injected MSCs are able to prevent the loss of function that occurs in mouse hearts following permanent coronary artery occlusion [18]. Furthermore, MSCs appear to be immunologically privileged [19], and can even be transplanted in large outbred animals across major histocompatibility complex barriers without the need for immune suppression [20].

In light of the modulatory effects of MSCs, they might have ideal properties to support the integration of stem-cell-derived CMs. Therefore, we investigated—for the first time to our knowledge—whether MSCs or soluble factors produced by MSCs modulate the structural and functional integration of iPS-CMs into myocardial tissue. For this purpose, we determined whether the engraftment of purified murine iPS derived CMs (iPS-CMs) into vital and nonvital cardiac tissue can be improved by coapplication of noncontractile MSCs or their conditioned medium (MSC-conditioned medium, MScond) [21] using a recently established in vitro coculture model [15,17,22].

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and media

Basic culture media were purchased from Life Sciences/Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany, www.invitrogen.com) and supplements and chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, www.sigma-aldrich.com), unless otherwise specified.

Animal care

All animal procedures were in accordance to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 86–23, revised 1985) and the current version of the German law on the Protection of Animals.

Generation of ventricular slices

Generation of ventricular tissue slices was performed as described previously [16]. Briefly, late-stage embryonic hearts (strain: Him:OF 1) were harvested on embryonic day 17.5. Ventricles were embedded in 4% low-melting agarose and sectioned into 300-μm-thick slices along the short axis with a microtome (Leica VT1000S; Leica Microsystems, Germany, www.leica-microsystems.com) using steel blades (Campden Instruments, Leicester, England, www.campdeninstruments.com). Ventricular slices were placed for 30 min in Ca2+-free, cold (4°C) Tyrode's solution (composition in mM: NaCl 136, KCl 5.4, NaH2PO4*2H2O 0.33, MgCl2*6H2O 1, d-glucose 10, HEPES 5, and 2,3-butanedione monoxime 30; pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH). After 30 min in cold Tyrode's solution with 0.9 mM Ca2+, the ventricular slices were transferred to Petri dishes that contain cold Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS), and then warmed in an incubator (37°C; 5% CO2). After 1 h of recovery under culture conditions, these vital slices were ready to be used and were plated onto multielectrode arrays (MEAs) at the day of preparation. Embryonic vital slices exhibit spontaneous beating for up to 14 days after preparation [23]. After 1 week at least 50% of the slices are still beating spontaneously [16].

Oxygen and glucose deprivation

Nonvital slices were generated by simulated hypoxia and ischemia, due to oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) for 45 h, as described previously [17]. These nonvital ventricular slices lost their contractile function and could be further used as a dead, natural, and soft cardiac matrix tissue for in vitro transplantation experiments and recording of contractile function mediated by iPS-CMs. OGD was performed by transferring the vital slices into a custom-made steel hypoxia chamber that was placed in a temperature bath maintained at 37°C. The chamber was filled with Tyrode's solution composed as described for the slicing procedure (with 1.5 mM of Ca2+) with the exception that d-glucose was replaced by an equimolar concentration of 2-deoxy-glucose (10 mM) to inhibit glucose metabolism. Oxygen tension was reduced by constant bubbling with pure nitrogen to induce hypoxia. After 45 h of OGD, the slices were washed twice in PBS to remove 2-deoxy-glucose, transferred to IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS, and then stored in an incubator under normal, normoxic conditions (37°C; 5% CO2, 21% O2) until coculturing with purified beating iPS-CM clusters, which was done on the same day.

IPS cell culture

Murine iPS cell line TiB7.4 was kindly provided by Meissner and Jaenisch (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA) [24]. For maintenance of pluripotency, iPS cells were grown on a monolayer of mitotically inactivated MEFs in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 15% FCS, 1% nonessential amino acids, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 μM β-mercaptoethanol (all from Invitrogen GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), and 1000 U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (ESGRO®; Millipore, Billerica, MA, www.millipore.com). The cells were stably genetically modified by plasmid electroporation to express enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) and a puromycin resistance under control of the cardiac-specific α-myosin heavy chain promoter [25]. To induce CM differentiation, transgenic iPS cells were transferred into IMDM containing 20% FCS, 100 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1% nonessential amino acids, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate in nonadherent plates. After 2 days of shaking, embryoid bodies (EBs) were formed and diluted to a density of 14,000 EBs/100 mL of differentiation medium and stirred continuously in spinner flasks (CellSpin 250; IBS INTEGRA Biosciences AG, Zizers, Switzerland, www.integra-biosciences.com) up to day 9 of differentiation. For purification of GFP-positive iPS-CM clusters, EBs were transferred onto nonadherent plates and selected for 5 days in the presence of puromycin (8 μg/mL; PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria, www.paa.com) with medium change every other day.

Isolation and expansion of murine MSCs and their conditioned medium

MSCs were isolated, expanded, and characterized as previously described [26]. Briefly, nucleated bone marrow cells were flushed from long bones of 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice and cultivated for 6–8 weeks under specific cell culture conditions based on the use of special MSC culture media (PAN Biotech, Aidenach, Germany, www.pan-biotech.com) and supplemented with 2.5 ng/mL human basic fibroblast growth factor (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany, www.rndsystems.com) until a proliferative and homogenous MSC population was obtained. To prove MSC status, cells were differentiated along adipogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic lineages by means of differentiation medium as described previously [26]. Surface expression of positive markers CD44 and Sca-1 and negative markers CD11b and CD45 was analyzed with fluorescently conjugated antibodies (all Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany, www.bd.com/de). MScond was generated as described previously [27]. In short, MSCs were cultured to a 70%–80% state of confluence, washed twice with IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The obtained supernatant was filtered with a 0.2-μm filter (Braun, Melsungen, Germany, www.bbraun.de) and used as a medium for cocultures.

Cell culture of MEFs

MEFs were generated as described previously [28]. Briefly, embryos (mouse strain: CD-1) were decapitated at day 14.5 post coitum and cut into small pieces after removal of extremities and inner organs. The tissue pieces were trypsinized, filtered, resuspended, and seeded into cell culture dishes in DMEM supplemented with 15% FCS. The cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. Medium was changed every second day. The cells were passaged up to three times at a ratio of 1:4 when they reached confluence.

Pre-incubation of nonvital ventricular slices with nonmyocytes

For coculturing, we used custom-made dishes that contained a small funnel-shaped cavity as described previously [12]. After placing the nonvital slices into the funnel-shaped cavity, 30 μL of a cell suspension containing 100,000 MEFs or MSCs was suspended over the slice. The small volumes were designed to maximize interactions between nonmyocytes and slices. After 30–45 min, iPS-CM clusters (15±3) were added at a volume of 70 μL IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS and placed beneath the slice. After another 2 h of incubation, 3 mL of fresh IMDM supplemented with 20% FCS was carefully added. About 1 mL medium out of the 3 mL total volume was changed daily.

Integration score

To describe the morphological integrations that were visible during coculture, a score was applied as described previously [12]. This so-called integration score used bright field, as well as fluorescent low-magnification, microscopy in order to unequivocally identify the GFP-positive iPS-CM clusters (Zeiss Axiovert 10, Germany; objective 2.5-fold or 5-fold), and video imaging to judge structural integration. Verbal descriptions and schematic drawings for pattern recognition were used for classification as described previously [12]. Briefly, attachment and integration was judged according to the position and shape of the iPS-CM clusters. “+” was given for an attached iPS-CM cluster with a normal round shape; “++ ” was given for attached and partially integrated iPS-CM clusters. These typically displayed a change in their shape in the form of a hump. “+++” was given for fully integrated iPS-CM clusters with a typical flat shape. Three investigators judged integration into nonvital tissue by the scoring system independently. The scoring samples were blinded to exclude personal bias. Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of this score were high with an intra-rater reliability (Spearman) of 0.86±0.01 and an inter-rater reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of 0.936. If the morphological integration of individual iPS-CM clusters differed within one preparation, then the clusters that exhibit the best integration were used for scoring (score+, physically attached; score+++, fully aligned).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

For immunohistological staining, preparations were fixed for 2 h in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, washed with PBS, and embedded in Tissue Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, www.sakura-finetek.com/). After cryoslicing, sections (8 μm) were placed on silanized slides. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-pan-cadherin (1:500; C3678, Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-GFP (1:100; AB38689, Abcam, Cambridge, UK, www.abcam.com). Primary antibodies were observed by anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 555 (1:1000; A21430, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, www.lifetechnologies.com) and anti-mouse IgG1-Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000; A21121, Invitrogen). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1:2000; 861529, Sigma-Aldrich). Images of stained preparations were acquired using a confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview FV1000) and the image-processing software FV1000 ASW (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany, www.olympus.de).

Isometric force measurements

After coculturing for 7 days, preparations of irreversibly ischemically damaged, noncontractile myocardial tissue with MEFs or MSCs and purified iPS-CM clusters were mounted onto an isometric force transducer (Scientific Instruments, Heidelberg, Germany, www.si-heidelberg.de), and amplified by a bridge amplifier (BAM7C; Scientific Instruments). Since the hearts were sliced orthogonally, the cavity of the left ventricle provided a preformed hole that eased mounting of the preparations onto the tips of two adjacent steel needles. This setup is very similar to the one used for force measurements of vascular rings [29]. Field stimulation was performed by silver electrodes (4 Hz, 10–25 V, pulse duration 5 ms) connected to a custom-made stimulator. The preparation was maintained at 37°C and immersed in a dish filled with Tyrode solution similar to the one used for slicing, but without 2,3-butanedione monoxime, and supplemented with 2 mM calcium and 2 mM sodium pyruvate. Electrical stimuli and analog signals from the force transducer (KG7A; range 0–5 mN, resolution 0.2 mN, resonance frequency 250–300 Hz) were amplified with a bridge amplifier (BAM7C; Scientific Instruments); analog signals were transferred to an analog-to-digital converter board and recorded as well as analyzed using the software DasyLab Version 7.0 (National Instruments, Munich, Germany, www.germany.ni.com).

Coculture of iPS-CMs and ventricular slices for field potential recordings

On the day of preparation, ventricular slices were plated on MEAs (Multi-Channel-Systems, Reutlingen, Germany, www.multichannelsystems.com). The MEAs used in this study had 60 TiN electrodes with diameters of 30 μm and inter-electrode distances of 200 μm arranged in eight rows and eight columns. For coculture of iPS-CMs with vital ventricular slices, single purified beating clusters on day 14 of differentiation with or without nonmyocytes (MEFs or MSCs) were pushed partially below a ventricular slice.

Field potential recordings

Field potential (FP) recordings were performed using an MEA amplifier 1060 (Multi Channel Systems). The temperature was kept at 37°C. The data were digitized with a sampling frequency of 5 kHz and recorded with the MC-Rack software (Multi Channel Systems).

Signal analysis was performed in MC-Rack to gain beating rates and peak profiles. FPs of nonintegrated iPS-CM clusters were distinct from FPs of ventricular slices by different morphology and smaller amplitude.

Mapping of impulse propagation

Mapping of impulse propagation was determined by a custom-made programmed mapping software based on “LabVIEW” (National Instruments, Houston, TX, www.ni.com). The time of maximal downstroke velocity (δV/δtmax) of the FP has been used to estimate the local activation time. Activation maps display the averaged time points of FP propagation over 60 MEA electrodes as a heat map [28].

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean. The significance was tested by one-way analysis of variance with a Tukey–Kramer post-test. Within each group, data were analyzed by paired t-test (two-tailed). The significance level was set to P<0.05 [(ns) P>0.05, significant (*) P<0.05, highly significant (**) P<0.01, and extremely significant (***) P<0.001]. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPadInStat version 3.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego California, CA, www.graphpad.com).

Results

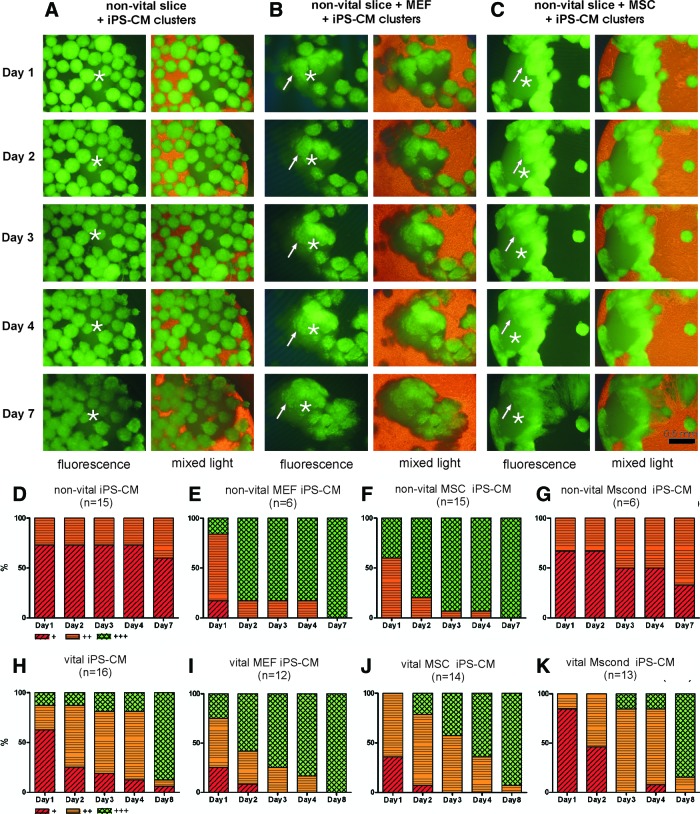

Morphological integration of murine iPS-CMs into nonvital and vital cardiac tissues

Integration was judged by the integration score as described previously. Integration into vital slices served as control. After 7 days of coculture, in-vitro-transplanted iPS-CM clusters attached, and eventually integrated completely into the vital slices (Fig. 1H). In 14 out of 16 preparations (87.5%) the best integrated iPS-CM clusters integrated completely into the vital slices and reached the highest integration score (Fig. 1H). Vital slices preincubated with MEFs, MSCs, or MScond, and subsequent coculturing with iPS-CM clusters, resulted in a similar good integration into vital slices (Fig. 1I–K). Nonvital slices without preincubation with MEFs, MSCs, or MScond showed only marginal attachment of iPS-CM clusters, and no complete integration (Fig. 1A, D). Even after 7 days of coculture not 1 of the 15 preparations with nonvital slices achieved the highest integration score (Fig. 1A, D). Preincubation with MEFs resulted in a clear improvement of integration of transplanted iPS-CM clusters into nonvital slices (Fig. 1B). All preparations reached the best integration score (6/6 preparations) after 7 days of coculture (Fig. 1E). Preincubation with MSCs also resulted in a clear improvement of integration of transplanted iPS-CM clusters into nonvital slices (Fig. 1C). The percentage of preparations reaching the best integration score amounted to 100% (15/15 preparations) after 7 days of coculture (Fig. 1F). Coculturing of nonvital slices with iPS-CM clusters in MScond did not result in an improved integration (Fig. 1G).

FIG. 1.

Sequential fluorescence microscopy and integration score for transplanted induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cardiomyocyte (iPS-CM) clusters. Integration of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–positive iPS-CM clusters (arrows) into a nonvital myocardial tissue slice without coculturing with murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (A), and a nonvital slice cocultured with MEFs (B) or MSCs (C) during an observation period of 7 days. iPS-CM clusters show only marginal attachment and no integration into the nonvital slice not cocultured with MEFs or MSCs. Coculturing with MEFs or MSCs results in a clear improved integration of iPS-CM clusters into the nonvital slices (B, C). Integration score for integration of iPS-CM clusters into nonvital slices without MEFs, MSCs, or MScond (D); nonvital slices cocultured with MEFs (E); nonvital slices cocultured with MSCs (F); nonvital slices cocultured in MScond (G); vital slices without MEFs, MSCs, or MScond (H); vital slices cocultured with MEFs (I); vital slices cocultured with MSCs (J); and vital slices cocultured in MScond (K). Scale bar=500 μm, * myocardial slice. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

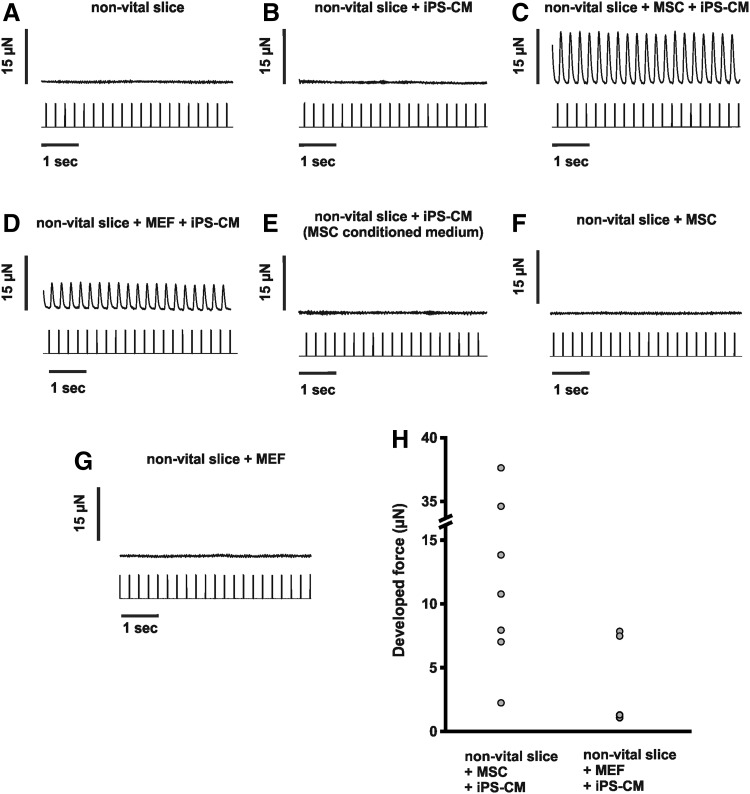

Force measurement

Since contractility is the pivotal quality of CMs, we analyzed whether iPS-CMs were able to confer force of contraction in our in vitro transplantation model [17] (Fig. 2). Myocardial tissue subjected to 45 h of simulated ischemia by OGD without iPS-CMs did not develop any force of contraction, not even when stimulated with higher than physiological electrical impulses (25 V, 100 ms, n=5; Fig. 2A). Cocultured preparations with iPS-CMs without preincubation with MEFs or MSCs were not able to confer force of contraction, due to limited morphological integration into the ventricular slices (n=5; Fig. 2B). Cocultured preparations with iPS-CMs after preincubation of the nonvital myocardial tissue with MEFs or MSCs (Fig. 2C, D) developed and conferred force of contraction. During electrical field stimulation with a frequency of 4 Hz, twitch amplitude increased to 16.3±5.3 μN (n=7) in the MSC-containing preparations (Fig. 2H) and to 4.4±1.9 μN (n=4) in the MEF-containing preparations (Fig. 2H). These values are not normalized to the number of transplanted CMs or cross-sectional area, because the total number of iPS-CMs and their alignment within the nonvital tissue slices cannot be standardized. Therefore, the absolute developed force of both groups cannot be compared. Preparations of nonvital slices that were not preincubated with nonmyocytes, but cultivated in MScond (n=5), were not able to confer force of contraction (Fig. 2E). Additionally, nonvital embryonic myocardial tissue slices cocultured with MSCs (n=6) or MEFs (n=6) but without addition of iPS-CMs did not develop any force of contraction, even when stimulated with higher than physiological electrical impulses (25 V, 100 ms; Fig. 2F, G).

FIG. 2.

Isometric force measurement. Representative traces from recordings of a nonvital myocardial tissue slice (A), a nonvital slice cocultured with iPS-CM clusters (B), nonvital tissue slices with iPS-CM clusters after preincubation with MSCs (C) or MEFs (D), a nonvital slice with iPS-CM clusters cultured in MScond (E), as well as nonvital slices cultured with MSCs (F) or MEFs (G) but without addition of iPS-CM clusters during electrical field stimulation at a frequency of 4 Hz. (H) Developed force of contraction from individual cocultured preparations that reveal contractions, that is, groups with iPS-CM clusters and preincubated with nonmyocytes (MSCs and MEFs). MEFs or MSCs are necessary to confer force.

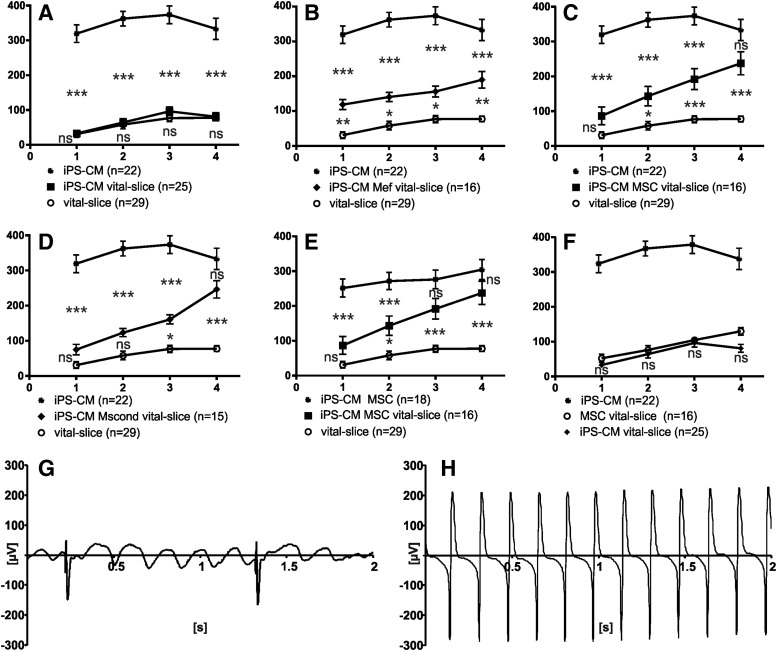

Beating rate

The beating rate of an iPS-CM cluster is ∼4-5 fold higher than the intrinsic spontaneous beating rate of vital slices. As a consequence, improved electrical integration of the iPS-CM cluster into the myocardial tissue typically results in a higher beating rate of the paced slice [22].

iPS-CM clusters displayed an average beating rate of 347±26 beats per minute (bpm; n=22; Fig. 3A–D, F). Vital slices had an average beating rate of 78 bpm±8 (n=29; P<0.001; Fig. 3A–E). Four days of coculture led in the case of efficient electrical coupling to subsequently elevated beating rates of myocardial slices.

FIG. 3.

Beating rate. Adaptation of the rapid beating rate of iPS-CM clusters and the lower rate of vital myocardial slices presented in beats per minute±standard error of the mean (Y-axis) over the course of 4 days (X-axis). (A) iPS-CM clusters beat at a higher rate than vital slices. Beating rates of vital slices were not statistically different from vital slices with iPS-CM clusters. (B–D) In cocultures with MEFs and MSCs as well as cultures in MScond, the beating rate of vital slices approximated the beating rate of iPS-CMs after 4 days. (E) On days 3 and 4, beating rates of vital slices cocultured with MSCs and iPS-CMs were comparable to beating rates of iPS-CMs cocultured with MSCs. (F) MSCs added to vital slices did not influence the beating behavior of the slice significantly. (G, H) Representative trace of a vital slice cocultured with an iPS-CM cluster alone with a low beating rate of the slice (signal with high amplitude) and a higher beating rate of the cluster (interfering signals with low amplitude) (G) and of a vital slice cocultured with an iPS-CM cluster and MSCs after 4 days of coculture, showing a high beating rate of the vital slice. The signal of the cluster is not distinguishable (H). Significance between each group is presented in asterisks.

The beating rate of vital slices did not change significantly after coculturing with iPS-CM clusters alone (n=25; day 4: 81±11 bpm; P>0.05; Fig. 3A). Beating frequency of vital slices with iPS-CM clusters and MEFs accelerated during coculture (day 1: MEFs n=16; 119±14 bpm; P<0.01; vs. day 4: MEFs 190±24 bpm; P<0.01; Fig. 3B). Vital slices cocultured with MSCs and iPS-CM clusters did not show a higher beating rate at day 1 of coculture compared with native vital slices (n=16; day 1: 87±25 bpm; P>0.05; Fig. 3C) but displayed a continuous acceleration of the beating rate until day 4 of coculture (day 4: 238±33 bpm; P<0.001; Fig. 3C).

To investigate whether soluble factors or cell–cell interactions of MSCs resulted in the observed beating elevation, we included MScond for further experiments. Vital slices cocultured with iPS-CM clusters in MScond displayed a beating behavior similar to cocultures with MSCs, with a clear increase in the beating frequency of the slice (n=15; day 1: 75±58 bpm; P>0.05–day 4: 246±95 bpm; P<0.001; Fig. 3D). The beating rate of vital slices cocultured with iPS-CM clusters and MEFs, MSCs, or MScond showed no statistical difference between each other on the fourth day of coculture (P>0.05).

Cocultures of vital slices with iPS-CM clusters and MSCs did not show statistically significant differences in beating rates at day 4 compared with a control group that consists of iPS-CM clusters and MSCs without a myocardial slice (day 4: n=16; 305±29 bpm; P>0.05; Fig. 3E). The beating rate of cocultured vital slices increased to levels comparable to those of iPS-CM clusters when cocultured with MSCs or MScond (P>0.05; Fig. 3C, D). Vital slices cocultured with MEFs and iPS-CMs showed an increase of beating rate during 4 days of coculture but did not reach the level of iPS-CM clusters (P<0.001; Fig. 3B).

To rule out a direct effect of MSCs on vital myocardial slices, cocultures of MSCs and vital tissue were performed in absence of iPS-CM clusters. These preparations did not differ statistically from beating rates of vital slices (n=16; 130±11 bpm; Fig. 3F).

These results indicate that electrical integration of iPS-CMs into cardiac tissue can be improved in the presence of supporting cells or soluble factors secreted by MSCs.

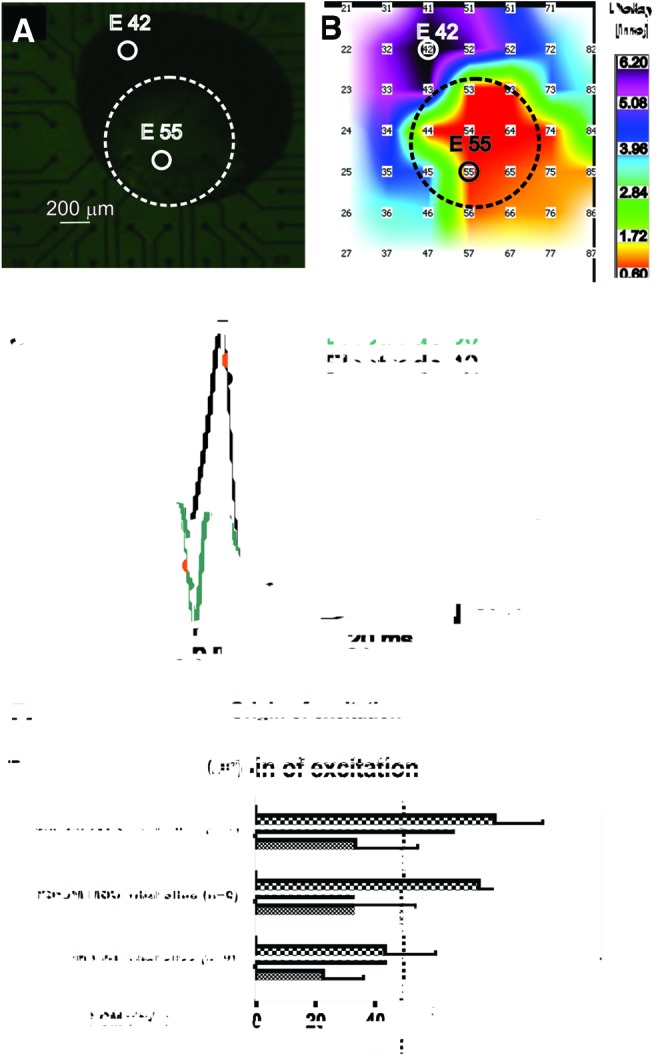

Origin of excitation

Activation maps were performed using recorded multielectrode array measurements of coculture preparations to confirm the GFP-positive area (iPS-CM clusters) as earliest signal appearance. Impulse propagation was determined by the local activation time (time of maximal downstroke velocity: δV/δtmax) as described previously [30]. Four ventricular slices served as a control and demonstrated a stable origin of excitation (OE) from within the same area of the ventricular slice on days 1–4 (data not shown). Vital slices cocultured with iPS-CM clusters alone displayed an OE change from 22.5%±36.1% on day 1 to 43.4%±48.3% on day 4 to the GFP-positive area (n=7; Fig. 4D). Cocultures of vital slices, iPS-CM clusters, and MEFs displayed an OE in the area around the GFP-positive clusters of 75%±41.8% on day 4 (n=6; Fig. 4D). Cocultures with MSCs and iPS-CM clusters showed an average OE of 80%±40% (n=7) in the GFP-positive area on day 4 (Fig. 4D). Vital slices and iPS-CM clusters without additional cells, but in MScond, showed an OE of 100%±0% in the area surrounding the GFP-positive clusters on day 4 (n=7; Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Origin of excitation (OE). (A) Example of a coculture preparation on multielectrode array [(combined bright field and fluorescence microscopy after 4 days of coculture; electrode 55 is covered by the GFP-positive iPS-CM cluster (encircled)]. (B) Spread of excitation: earliest activation of the slice (red) is close to the iPS-CM cluster (marked by the dashed circle). (C) Calculation of local activation time and corresponding field potentials (FPs): FP of electrode 55 (lower FP curve) and FP of electrode 42 (upper FP curve). Local activation times (dots) were calculated as the minimum of the derivative of the FPs. (D) OE changes over the coculture period of 4 days depending on type of coculture in relation to the area close to the iPS-CM cluster in percentage (X-axis). Significance between each group is presented in asterisks. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Immunohistochemistry

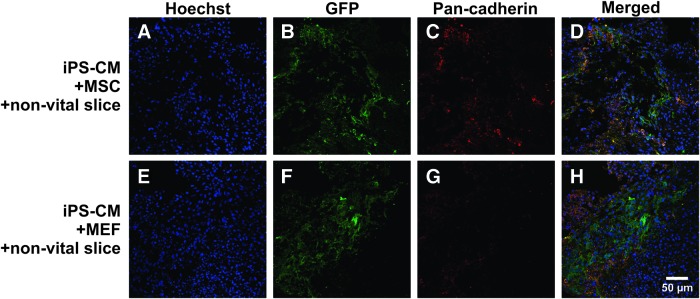

Immunostaining was performed to elucidate the mechanisms that cause the improved integration of iPS-CM clusters into nonvital slices after preincubation with MSCs or MEFs. Confocal imaging reveals a colocalization of pan-cadherin and the iPS-CM clusters within the nonvital slice (Fig. 5). The formation of pan-cadherin in the close proximity of iPS-CMs indicates a cell–cell interaction and is a potential mediator of the structural integration observed in the force measurement experiments.

FIG. 5.

Distribution of pan-cadherin after 4 days of coculture. Confocal microscopy of immunohistochemistry of a nonvital slice cocultured with iPS-CMs and MSCs (A–D) and MEFs (E–H), respectively. Nuclear material is stained with Hoechst (blue: A, D, E, H). GFP-positive iPS-CMs (green: B, D, F, H) structurally integrate into the nonvital myocardial slice. Formation of pan-cadherin (red: C, D, G, H) in the close proximity of iPS-CMs is a potential mediator of the structural integration observed in the force measurement experiments. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Discussion

In this study, clusters of purified iPS-CMs attach and integrate inefficiently into vital myocardial tissue. Myocardial tissue that had been subjected to ischemia treatment did not support integration at all. Attachment, integration, and force transmission of iPS-CMs could be reconstituted by the presence of MSCs. Furthermore, addition of MSCs resulted in a clear improvement of the electrical coupling of purified iPS-CMs into vital tissue slices. A similar improvement of electrical coupling was achieved by adding cell-free MScond to slices cocultured with iPS-CMs, indicating that soluble factors secreted by MSCs are responsible for the improvement in electrical coupling of iPS-CMs to vital tissue slices but not for morphological integration.

The observed inability of purified iPS-CMs to integrate into nonvital myocardial tissue resembles our experiences with purified ES-CMs [12]. Coculturing of purified iPS-CMs with slices preincubated with MEFs or MSCs resulted in a clear improved integration of CMs into nonvital tissue. It is possible that the beneficial effect of MSCs might be partially mediated by enhancing the migration efficiency of the transplanted CMs, an effect that has been demonstrated for MEFs in our previous study [12].

Multiple lines of evidence show that MSCs can migrate to damaged tissues [31–36]. For example, stromal-cell-derived factor 1 has been found to increase after myocardial infarction and in heart failure [37–39], and its chemoattractant properties have been demonstrated to enhance the recruitment of circulating hematopoietic stem cells to the infarcted myocardium [40,41]. In a recent study, Wnt5a, which is expressed also by MSCs [41,42], was identified as a chemoattractant for human ES-CMs [43]. The addition of MSCs, which migrate and integrate into the myocardial tissue, might therefore help to activate a migration of transplanted CMs, explaining at least in part the superior integration of iPS-CMs into nonvital slice tissue found in the present study. Confocal imaging revealed a colocalization of pan-cadherin and the iPS-CM clusters within the nonvital slice after coculture with MEFs or MSCs. The formation of pan-cadherin indicates a cell–cell interaction and is a potential mediator of the structural integration observed in the force measurement experiments. Further studies will be necessary to elucidate the exact nature of the cell–cell contacts.

Morphological integration and force transmission of iPS-CMs into the nonvital matrix was only possible in cocultures with MEFs or MSCs. Cocultures without cellular components such as MScond failed to support morphological integration into nonvital tissue, indicating the necessity of cellular elements. This is in line with a previous report that indicates that MEFs are required for integration of purified ES-CMs in a synthetic collagen type I matrix [11].

One prerequisite for a successful transplantation is electrical integration. Grafts may regenerate the heart but they also could increase the likelihood of arrhythmias by slow-conduction properties [44–47]. Further, inefficient coupling of transplanted iPS-CMs would limit their therapeutic effect.

We were able to show that functional and electrical integration of purified iPS-CMs was clearly improved by cotransplantation of nonmyocytes. Coculturing of purified iPS-CMs with vital myocardial slices alone did not result in an increase of the beating rate of the slices. One reason could be the current generated by the much smaller and not well-integrated iPS-CM clusters, which might disperse in the well-coupled gap junction network of the ventricular slice, leading to current-to-load mismatches [22]. Cotransplanted nonmyocytes improve the integration of iPS-CM clusters into myocardial tissue and therefore establish contact of more cells of the cluster with the slice, which might result in better conditions for the spread of excitation. Several groups have shown that CMs in a distance of about 300–400 μm can be synchronized by bridging via cardiac fibroblasts or MSCs [44,48,49], which would optimize the current generated by the iPS-CM cluster. By performing activation maps, we were able to show that the elevated beating rate in the cocultured preparations correlates to an OE from the region around the iPS-CM clusters. This suggests that the iPS-CM clusters are responsible for the higher beating rates of the slice, and are not caused by an increase of spontaneous activity of the slice itself. Interestingly, cocultures in cell-free MScond accelerated the beating rate of the slice, indicating that soluble factors secreted by MSCs result in comparable effects on the electrical integration of iPS-CMs into vital myocardial tissue.

Other studies support this observation; components of the MSC secretome, like VEGF [50] and Wnt1 [51], have been reported to modulate cardiac gap junction expression [52,53]. Mureli et al. [54] demonstrated an increased conduction velocity of HL-1 cells by adding MSC culture media or tyrode that was conditioned by mouse or human MSCs [54]. Furthermore, they were able to show a subsequent upregulation of Cx43 in HL-1 cells [54]. In a recent study, DeSantiago et al. [55] demonstrated that when isolated mouse ventricular myocytes were treated with MSC-conditioned tyrode, they had an immediate impact on the myocyte physiological properties of excitation-contraction coupling, with a time-dependent increase of the calcium transient amplitude and acceleration of the calcium transient decay [55]. Voltage clamp recordings confirmed that an MSC-conditioned tyrode induced increase of the L-type calcium current [55]. These studies indicate that MSCs and their secretome modulate CM function via multiple mechanisms.

In conclusion, purified iPS-CMs do not integrate into nonvital myocardial tissue and thus cannot transfer force of contraction. Vital cells like MSCs are necessary to enable migration of iPS-CMs and their engraftment, adhesion, and force transmission to noncontractile tissue. Furthermore, soluble factors secreted by MSCs resulted in an improved electrical coupling of purified iPS-CM clusters to vital myocardial tissue.

This study provides further evidence that MSCs, or components of their conditioned medium, improve the integration of transplanted iPS-CMs. This could be another step toward a successful cell-replacement strategy.

Future studies will have to define the optimal relation of CMs to nonmyocytes and to analyze the properties of MSC-secreted factors and their influence on transplanted stem-cell-derived CMs in more detail.

Limitations

We applied MEAs to assess the functional (electrical) integration over a time period of 4 days. Therefore we needed viable myocardial tissue slices, which should be contractile for at least 4–5 days. Adult myocardial slices lose their ability to contract a few hours after the slicing procedure [56]. Embryonic myocardial slices are a well-established tool to study electrophysiological properties and have been described in several studies [15,22] and are contractile for up to 14 days [23]. Nevertheless, it cannot be excluded that a coculture model using adult myocardial tissue would behave differently.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ingrid Kaul and the Institute for Medical Statistics, Informatics and Epidemiology for the statistical analysis. We thank Cornelia Boettinger, Nadin Piekarek, and Daniel Derichsweiler for technical assistance; Karsten Burkert for iPS-CM characterization; and Suzanne Wood for editorial assistance. This study was supported by a grant from the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) to M.K., K.B., J.H., T.S., and Y.H.-C. (grant no. 01GN0947).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Eschenhagen T. and Zimmermann WH. (2005). Engineering myocardial tissue. Circ Res 97:1220–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laflamme MA. and Murry CE. (2005). Heart regeneration. Nature 473:326–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubart M. and Field LJ. (2006). Cardiac regeneration: repopulating the heart. Annu Rev Physiol 68:29–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laugwitz KL, Moretti A, Lam J, Gruber P, Chen Y, Woodard S, Lin LZ, Cai CL, Lu MM, et al. (2005). Postnatal isl1+cardioblasts enter fully differentiated cardiomyocyte lineages. Nature 433:647–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Yamada S, Perez-Terzic C, Ikeda Y. and Terzic A. (2009). Repair of acute myocardial infarction by human stemness factors induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation 120:408–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter L, Carr C, Yang CT, Stuckey DJ, Clarke K. and Watt SM. (2012). Efficient differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells generates cardiac cells that provide protection following myocardial infarction in the rat. Stem Cells Dev 21:977–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laflamme MA, Zbinden S, Epstein SE. and Murry CE. (2007). Cell-based therapy for myocardial ischemia and infarction: pathophysiological mechanisms. Annu Rev Pathol 2:307–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.vanLaake LW, Passier R, Monshouwer-Kloots J, Verkleij AJ, Lips DJ, Freund C, den Ouden K, Ward-van Oostwaard D, Korving J, et al. (2007). Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes survive and mature in the mouse heart and transiently improve function after myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res 1:9–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolossov E, Bostani T, Roell W, Breitbach M, Pillekamp F, Nygren JM, Sasse P, Rubenchik O, Fries JW, et al. (2006). Engraftment of engineered ES cell-derived cardiomyocytes but not BM cells restores contractile function to the infarcted myocardium. J Exp Med 203:2315–2327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hattori F, Chen H, Yamashita H, Tohyama S, Satoh YS, Yuasa S, Li W, Yamakawa H, Tanaka T, et al. (2010). Nongenetic method for purifying stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods 7:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfannkuche K, Neuss S, Pillekamp F, Frenzel LP, Attia W, Hannes T, Salber J, Hoss M, Zenke M, et al. (2010). Fibroblasts facilitate the engraftment of embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes on three-dimensional collagen matrices and aggregation in hanging drops. Stem Cells Dev 19:1589–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xi J, Khalil M, Spitkovsky D, Hannes T, Pfannkuche K, Bloch W, Saric T, Brockmeier K, Hescheler J. and Pillekamp F. (2011). Fibroblasts support functional integration of purified embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes into avital myocardial tissue. Stem Cells Dev 20:821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubart M, Pasumarthi KB, Nakajima H, Soonpaa MH, Nakajima HO. and Field LJ. (2003). Physiological coupling of donor and host cardiomyocytes after cellular transplantation. Circ Res 92:1217–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubart M. (2004). Two-photon microscopy of cells and tissue. Circ Res 95:1154–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pillekamp F, Halbach M, Reppel M, Pfannkuche K, Nazzal R, Nguemo F, Matzkies M, Rubenchyk O, Hannes T, et al. (2009). Physiological differences between transplanted and host tissue cause functional decoupling after in vitro transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem 23:65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pillekamp F, Reppel M, Dinkelacker V, Duan Y, Jazmati N, Bloch W, Brockmeier K, Hescheler J, Fleischmann BK. and Koehling R. (2005). Establishment and characterization of a mouse embryonic heart slice preparation. Cell Physiol Biochem 16:127–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillekamp F, Reppel M, Rubenchyk O, Pfannkuche K, Matzkies M, Bloch W, Sreeram N, Brockmeier K. and Hescheler J. (2007). Force measurements of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes in an in vitro transplantation model. Stem Cells 25:174–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boomsma RA. and Geenen DL. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells secrete multiple cytokines that promote angiogenesis and have contrasting effects on chemotaxis and apoptosis. PLoS One 7:e35685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Blanc K. (2003). Immunomodulatory effects of fetal and adult mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy 5:485–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devine SM, Cobbs C, Jennings M, Bartholomew A. and Hoffman R. (2003). Mesenchymal stem cells distribute to a wide range of tissues following systemic infusion into nonhuman primates. Blood 101:2999–3001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connell JP, Augustini E, Moise KJ, Jr., Johnson A. and Jacot JG. (2013). Formation of functional gap junctions in amniotic fluid-derived stem cells induced by transmembrane co-culture with neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. J Cell Mol Med 2:12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannes T, Halbach M, Nazzal R, Frenzel L, Saric T, Khalil M, Hescheler J, Brockmeier K. and Pillekamp F. (2008). Biological pacemakers: characterization in an in vitro coculture model. J Electrocardiol 41:562–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupu M, Khalil M, Iordache F, Andrei E, Pfannkuche K, Spitkovsky D, Baumgartner S, Rubach M, Abdelrazik H, et al. (2011). Direct contact of umbilical cord blood endothelial progenitors with living cardiac tissue is a requirement for vascular tube-like structures formation. J Cell Mol Med 15:1914–1926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meissner A, Wernig M. and Jaenisch R. (2007). Direct reprogramming of genetically unmodified fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 25:1177–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguemo F, Saric T, Pfannkuche K, Watzele M, Reppel M. and Hescheler J. (2012). In vitro model for assessing arrhythmogenic properties of drugs based on high-resolution impedance measurements. Cell Physiol Biochem 29:819–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drey F, Choi YH, Neef K, Ewert B, Tenbrock A, Treskes P, Bovenschulte H, Liakopoulos OJ, Brenkmann M, et al. (2013). Noninvasive in vivo tracking of mesenchymal stem cells and evaluation of cell therapeutic effects in a murine model using a clinical 3.0 T MRI. Cell Transplant 11:1971–1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voulgari-Kokota A, Fairless R, Karamita M, Kyrargyri V, Tseveleki V, Evangelidou M, Delorme B, Charbord P, Diem R. and Probert L. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells protect CNS neurons against glutamate excitotoxicity by inhibiting glutamate receptor expression and function. Exp Neurol 236:161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gissel C, Doss MX, Hippler-Altenburg R, Hescheler J. and Sachinidis A. (2006). Generation and characterization of cardiomyocytes under serum-free conditions. Methods Mol Biol 330:191–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angus JA. and Wright CE. (2000). Techniques to study the pharmacodynamics of isolated large and small blood vessels. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 44:395–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pillekamp F, Reppel M, Brockmeier K. and Hescheler J. (2006). Impulse propagation in latestage embryonic and neonatal murine ventricular slices. J Electrocardiol 39:425.e1–e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aghi M. and Chiocca EA. (2005). Contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to blood vessels in ischemic tissues and tumors. Mol Ther 12:994–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang SK, Shin IS, Ko MS, Jo JY. and Ra JC. (2012). Journey of mesenchymal stem cells for homing: strategies to enhance efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Int 2012: Article ID 342968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu X, Wang J, Chen J, Luo R, He A, Xie X. and Li J. (2007). Optimal temporal delivery of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in rats with myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 31:438–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petit I, Jin D. and Rafii S. (2007). The SDF-1-CXCR4 signaling pathway: a molecular hub modulating neo-angiogenesis. Trends Immunol 28:299–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ceradini DJ. and Gurtner GC. (2005). Homing to hypoxia: HIF-1 as a mediator of progenitor cell recruitment to injured tissue. Trends Cardiovasc Med 15:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lima e Silva R, Shen J, Hackett SF, Kachi S, Akiyama H, Kiuchi K, Yokoi K, Hatara MC, Lauer T, et al. (2007). The SDF-1/CXCR4 ligand/receptor pair is an important contributor to several types of ocular neovascularization. Faseb J 21:3219–3230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leone AM, Rutella S, Bonanno G, Contemi AM, de Ritis DG, Giannico MB, Rebuzzi AG, Leone G. and Crea F. (2006). Endogenous G-CSF and CD34+cell mobilization after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 111:202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamani MH, Ratliff NB, Cook DJ, Tuzcu EM, Yu Y, Hobbs R, Rincon G, Bott-Silverman C, Young JB, Smedira N. and Starling RC. (2005). Peritransplant ischemic injury is associated with up-regulation of stromal cell-derived factor-1. J Am Coll Cardiol 46:1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma N, Stamm C, Kaminski A, Li W, Kleine HD, Muller-Hilke B, Zhang L, Ladilov Y, Egger D. and Steinhoff G. (2005). Human cord blood cells induce angiogenesis following myocardial infarction in NOD/scid-mice. Cardiovasc Res 66:45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Askari AT, Unzek S, Popovic ZB, Goldman CK, Forudi F, Kiedrowski M, Rovner A, Ellis SG, Thomas JD, et al. (2003). Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 362:697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abbott JD, Huang Y, Liu D, Hickey R, Krause DS. and Giordano FJ. (2004). Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha plays a critical role in stem cell recruitment to the heart after myocardial infarction but is not sufficient to induce homing in the absence of injury. Circulation 110:3300–3305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markov V, Kusumi K, Tadesse MG, William DA, Hall DM, Lounev V, Carlton A, Leonard J, Cohen RI, Rappaport EF. and Saitta B. (2007). Identification of cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cell populations with distinct growth kinetics, differentiation potentials, and gene expression profiles. Stem Cells Dev 16:53–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moyes KW, Sip CG, Obenza W, Yang E, Horst C, Welikson RE, Hauschka SD, Folch A. and Laflamme MA. (2013). Human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes migrate in response to gradients of fibronectin and Wnt5a. Stem Cells Dev 22:2315–2325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beeres SL, Atsma DE, van der Laarse A, Pijnappels DA, van Tuyn J, Fibbe WE, de Vries AA, Ypey DL, van der Wall EE. and Schalij MJ. (2005). Human adult bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells repair experimental conduction block in rat cardiomyocyte cultures. J Am Coll Cardiol 46:1943–1952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kehat I. and Gepstein L. (2007). Electrophysiological coupling of transplanted cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 101:433–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofshi A, Itzhaki I, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Gross GJ. and Gepstein L. (2011). A combined gene and cell therapy approach for restoration of conduction. Heart Rhythm 8:121–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pijnappels DA, Schalij MJ, van Tuyn J, Ypey DL, de Vries AA, van der Wall EE, van der Laarse A. and Atsma DE. (2006). Progressive increase in conduction velocity across human mesenchymal stem cells is mediated by enhanced electrical coupling. Cardiovasc Res 72:282–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaudesius G, Miragoli M, Thomas SP. and Rohr S. (2003). Coupling of cardiac electrical activity over extended distances by fibroblasts of cardiac origin. Circ Res 93:421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rook MB, van Ginneken AC, de Jonge B, el Aoumari A, Gros D. and Jongsma HJ. (1992). Differences in gap junction channels between cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, and heterologous pairs. Am J Physiol 263:C959–C977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markel TA, Wang Y, Herrmann JL, Crisostomo PR, Wang M, Novotny NM, Herring CM, Tan J, Lahm T. and Meldrum DR. (2008). VEGF is critical for stem cell-mediated cardioprotection and a crucial paracrine factor for defining the age threshold in adult and neonatal stem cell function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295:H2308–H2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leroux L, Descamps B, Tojais NF, Seguy B, Oses P, Moreau C, Daret D, Ivanovic Z, Boiron JM, et al. (2010). Hypoxia preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells improve vascular and skeletal muscle fiber regeneration after ischemia through a Wnt4-dependent pathway. Mol Ther 18:1545–1552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ai Z, Fischer A, Spray DC, Brown AM. and Fishman GI. (2000).Wnt-1 regulation of connexin43 in cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest 105:161–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pimentel RC, Yamada KA, Kleber AG. and Saffitz JE. (2002). Autocrine regulation of myocyte Cx43 expression by VEGF. Circ Res 90:671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mureli S, Gans CP, Bare DJ, Geenen DL, Kumar NM. and Banach K. (2013). Mesenchymal stem cells improve cardiac conduction by upregulation of connexin 43 through paracrine signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304:600–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeSantiago J, Bare DJ, Semenov I, Minshall RD, Geenen DL, Wolska BM. and Banach K. (2012). Excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular myocytes is enhanced by paracrine signaling from mesenchymal stem cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 52:1249–1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halbach M, Pillekamp F, Brockmeier K, Hescheler J, Müller-Ehmsen J. and Reppel M. (2006). Ventricular slices of adult mouse hearts—a new multicellular in vitro model for electrophysiological studies. Cell Physiol Biochem 18:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]