To the Editor: Idiopathic calcification of the mitral annulus is one of the most common cardiac abnormalities demonstrated at autopsy (1). Currently, the pathophysiology of mitral annular calcification (MAC) is viewed as a passive degenerative process due to a buildup of calcium along the mitral valve leaflet and annulus. Recent epidemiologic studies have defined the risk factors for the development of MAC, which include hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, and male gender (2–4). These reports also have examined the association between mitral valve calcification and atherosclerosis; however, few experimental models have demonstrated these changes. Atherosclerosis is established as an active, cellular process within the vessel wall activated by an inflammatory mechanism (5). The mitral annulus and aortic valve cusps follow the coronary arteries as the most common sites of cardiac calcifications (6,7). Our laboratory has shown that experimental hypercholesterolemia induces an atherosclerotic aortic valve lesion that expresses bone matrix proteins that are modified by atorvastatin (8). In the present study, we examined experimental hypercholesterolemia with and without atorvastatin in rabbits and characterized the mitral valves.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (IACUC A282–99). Male New Zealand white rabbits weighing 2.5 to 3.0 kg were assigned to a control diet (n = 16), 1.0% cholesterol-fed diet (n = 16), or cholesterol- and atorvastatin-fed diet (n = 16) for eight weeks. Cholesterol-fed animals received a diet supplemented with 1.0% cholesterol (wt/wt; Purina Mills, Woodmont, Indiana), and the cholesterol- and atorvastatin-fed group was given atorvastatin at 2.5 mg/kg/day. Lipid levels were obtained. The mitral valves were harvested and embedded in paraffin and stored at −80°C for RNA analysis. Immunohistochemistry was performed for the atherosclerotic markers alpha-actin, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and macrophage (RAM11). Semiquantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction for osteopontin (OP) was performed. All experimental studies were performed as described previously (8). The samples were scored semiquantitatively by two observers who were blinded to the treatment arms, and the results were expressed qualitatively and demonstrated in the photomicrographs. No systematic differences existed between readers in the grading of stains by paired t tests (p = 0.33). The kappa value for agreement between readers was 0.58, indicating moderate agreement. Comparison was made among the three groups using analysis of variance. The Scheffe method of adjustment was performed for multiple pairwise comparisons. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. The data are reported as the mean and the standard error of the mean.

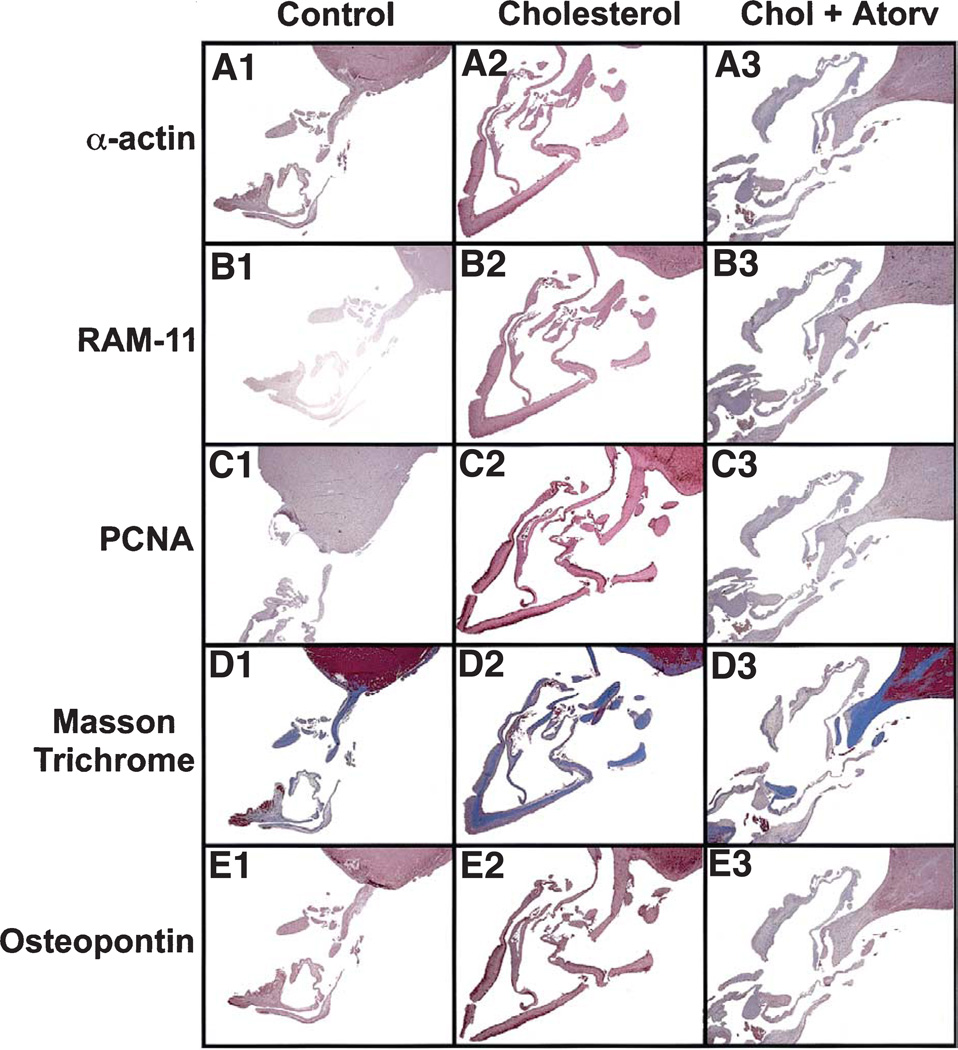

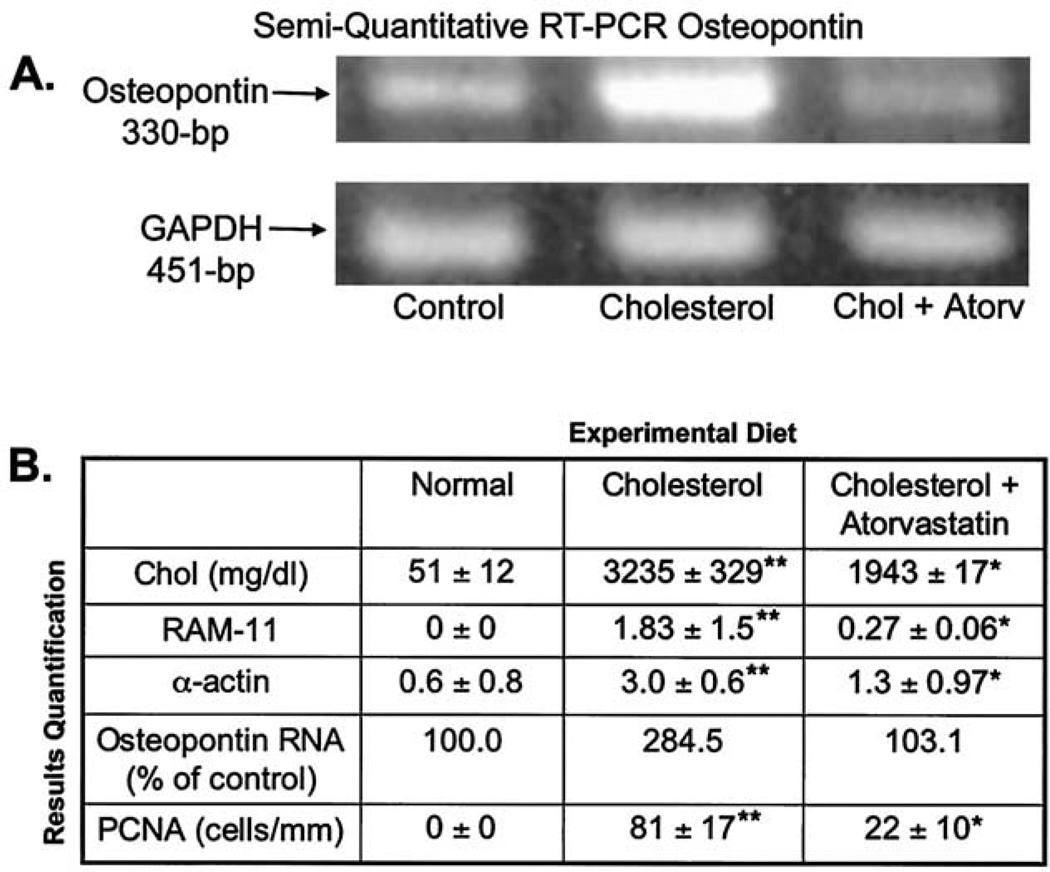

The normal mitral valve in Figure 1, panel A1 shows a thin, intact valve attached to the papillary muscle as demonstrated by the alpha-actin immunostain. Furthermore, there was no evidence of foam cell formation (Fig. 1, B1), cellular proliferation (Fig. 1, C1), calcification shown by Masson trichrome staining (Fig. 1, D1), or OP deposition (Fig. 1, E1). However, mitral valves from the hypercholesterolemic showed a considerable increase in connective tissue and collagen formation (Fig. 1, D2). Likewise, there were focal areas of increased myofibroblast proliferating cell nuclear antigen staining and alpha-actin–positive staining cells (Fig. 1, A2 and C2), as well as areas staining positive for macrophages (RAM11), suggesting foam cell infiltration (Fig. 1, B2). Finally, there was significant deposition of OP within the mitral valve leaflet, which was not observed in the controls (Fig. 1, E2). Figure 1, panels A3 to E3 demonstrate the effects of the atorvastatin on the mitral valve for all of these treatments with marked improvement in the atherosclerotic lesion. We further confirmed the OP RNA expression in Figure 2A. There were significantly increased levels of OP RNA gene expression in the hypercholesterolemic animals compared with either the control or atorvastatin-treated animals. Figure 2B, demonstrates significant decreases in the amount of all the immunohistochemical markers with atorvastatin treatment.

Figure 1.

Light microscopy of rabbit mitral valves and papillary muscle. Left column = control diet; middle column = cholesterol diet with the arrow pointing to the valve leaflet; right column = cholesterol diet plus atorvastatin. (All frames: magnification, ×12.) (A) Alpha-actin immunostain. (B) RAM-11, macrophage immunostain. (C) Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) immunostain. (D) Masson trichrome stain. (E) Osteopontin immunostain.

Figure 2.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantification data. (A) RT-PCR using the total ribonucleic acid (RNA) from the aortic valves for osteopontin (330 bp) results normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (451 bp). (B) Quantification results for cholesterol levels, RAM-11, alpha-actin, osteopontin, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and osteopontin RNA results. **p < 0.001 compared with control; *p < 0.001 compared with high-cholesterol diet.

It is evident from this experimental model that mitral valve calcification represent an active, complex process involving myofibroblast proliferation and osteoblast bone matrix protein expression and that this process may be modified by atorvastatin. There have been numerous studies that correlate MAC and atherosclerotic disease. The clinical significance of MAC includes increased development of aortic atheromas, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease (9–11). These findings suggest that MAC should be added to other conventional risk factors for predicting coronary artery disease, as it may indicate a generalized atherosclerotic process within the valves and vasculature. The appearance of mitral valve calcifications may indicate a generalized atherosclerotic process and be predictive of coronary artery disease, suggesting that it should be included with other risk factors for coronary artery disease. Atorvastatin treatment reduces the cellular proliferation and early bone matrix expression, which may have implications for future treatment of patients in the early stages of MAC. The limitation of this study is the effect demonstrated in this study was found throughout the valve leaflet, including the mitral annulus. Future studies, including longer duration of cholesterol diet, are needed to demonstrate calcification in the future.

Footnotes

Please note: Dr. Rajamannan is an inventor on a patent assigned to the Mayo Clinic titled “Method for Slowing Heart Valve Degeneration.” The Mayo Clinic owns all rights to the patent.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonow RO, Braunwald E. Valvular heart disease. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braunwald E, editors. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 7th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Science; 2004. pp. 1553–1621. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boon A, Cheriex E, Lodder J, Kessels F. Cardiac valve calcification: characteristics of patients with calcification of the mitral annulus or aortic valve. Heart. 1997;78:472–474. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.5.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nair CK, Subdhakaran C, Aronow WS, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients younger than 60 years with mitral annular calcium: comparison with age and sex matched control subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1984;54:1286–1287. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(84)80082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronow WS, Schwartz KS, Koenigsberg M. Correlation of serum lipids, calcium and phosphorus, diabetes mellitus, aortic valve stenosis: a history of systemic hypertension with presence or absence of mitral annular calcium in persons older than 62 years in a long-term health care facility. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59:381–382. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts WC. The senile cardiac calcification syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58:572–574. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts WC. Morphologic features of the normal and abnormal mitral valve. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:1005–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajamannan NM, Subramaniam M, Springett M, et al. Atorvastatin inhibits hypercholesterolemia-induced cellular proliferation and bone matrix production in the rabbit aortic valve. Circulation. 2002;105:2260–2265. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017435.87463.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adler Y, Koren A, Fink N, et al. Association between mitral annulus calcification and carotid atherosclerotic disease. Stroke. 1998;29:1833–1837. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.9.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler Y, Zabarski RS, Vaturi M, et al. Association between mitral annulus calcification and aortic atheroma as detected by transesophageal echocardiographic study. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:784–786. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)01014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler Y, Vaturi M, Wiser I, et al. Nonobstructive aortic valve calcium as a window to atherosclerosis of the aorta. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:68–71. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]