Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) below the age of 65 often presents with an atypical, non-memory presentations that may be difficult to recognize as due to AD 1. In the absence of a relatively determinative test or biomarker, these patients often remain undiagnosed in their earliest stages, when therapeutic and psychosocial intervention may be most helpful. This situation, however, may change with the recent clinical availability of amyloid neuroimaging.

Logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA), or the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia (PPA), is a language impairment that is one of the known variant presentations of early-onset AD 1. The criteria for LPA include the presence of both impaired single-word retrieval in spontaneous speech and naming and impaired repetition of sentences and phrases 2. LPA also has at least two of the following: speech (phonological) errors; spared single-word comprehension; spared motor speech; and absence of frank agrammatism 2. LPA can be difficult to distinguish from the non-fluent/agrammatic variant of PPA aphasia associated with frontotemporal degeneration pathology (FTLD). In fact, there is much overlap between the different clinical syndromes of PPA, and the clinical examination by itself may be insufficient or unreliable for predicting AD or FTLD pathology 3.

The clinical availability of amyloid neuroimaging with [18F]florbetapir (Amyvid®) may facilitate the recognition of LPA as due to Alzheimer-related amyloid pathology. Florbetapir is the first FDA-approved radioactive diagnostic agent, used with positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, for visualizing fibrillar amyloid plaques in patients with possible AD 4. A positive scan corresponds to β-amyloid deposition in the brain in people with AD, as well as some people on aging 4. Among patients with early-onset cognitive difficulties, however, the presence of a positive florbetapir scan is a good indicator of Alzheimer pathology.

We present three patients with LPA, compared to three age-matched patients with typical amnestic AD, on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and florbetapir PET imaging. These patients illustrate that clinical florbetapir imaging can support the presence of amyloid pathology in cognitive variants of early-onset AD.

Methods

Participants

This report includes three patients who presented to a university clinic specializing in early-onset dementia and met published criteria for LPA 2. They were matched on approximate age, gender, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores with an additional three patients from the same clinic who met criteria for AD 5.

As part of the clinical evaluation, these patients underwent florbetapir PET imaging. We obtained the images on a Siemens 953/31 PET scanner (voxel size 1.96×1.96×3.38 mm, Siemens Medical Solutions, Hoffman Estates, Illinois). Eli Lilly/AVID pharmaceuticals Inc. provided the [18F]florbetapir tracer. We injected the patients with a 10mCi dose and obtained 20 minute images 50-70 min after dose injection. Trained neuroimagers (AmyvidTraining.com) read the scans as positive or negative depending on the attenuation of the normal gray-white contrast differences.

Neurocognitive testing included the following 6: MMSE, digit span forward, “F” letter and “animal” category word-list generation, 20-item extended mini-Boston Naming Test, dysfluency scale (words/minute, phrase length, effort, halting), sentence repetition, word and sentence comprehension, Consortium to Establish a Registry in AD (CERAD) delayed recall, 12 item constructional figures, Perceptual Assessment Battery (PAB), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), calculations screen, ideomotor apraxia screen, Frontal Assessment Battery, and four proverb interpretations (from Delis-Kaplan set).

Results

There were no differences in age, age of onset, education, or most neurocognitive measures (See Table). Memory testing did not distinguish the LPA and AD patients in this small sample. The LPA patients, however, were more impaired on dysfluency and sentence repetition, and the AD patients were more impaired on constructions and visuoperceptual (PAB) measures.

Table 1. Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA) vs. Alzheimer's Disease (AD).

| LPA A | LPA B | LPA C | AD D | AD E | AD F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59 | 65 | 62 | 51 | 58 | 56 |

| Onset age (years) | 52 | 62 | 60 | 49 | 56 | 54 |

| Sex (M/F) | M | F | M | M | F | M |

| Education (years) | 20 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 20 | 16 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | 29 | 299 | 28 | 29 | 27 | 29 |

| Digit Span | 4 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| “F” Word-List Generation | 11 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 4 | 9 |

| Category Word-List Generation | 28 | 21 | 25 | 22 | 14 | 19 |

| ADysfluency Scale (14) | 6 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Ext mini-Boston Naming Test (20) | 19 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 16 | 20 |

| BSentence Repetition (5) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Word Comprehension (12) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Sentence Comprehension (20) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 |

| CERAD Delayed Recall (10) | 4 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| CConstructions (12) | 12 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 7 |

| DPerceptual Assessment Battery (18) | 18 | 18 | 18 | 9 | 10 | 15 |

| Frontal Assessment Battery (18) | 18 | 18 | 17 | 18 | 8 | 12 |

| Calculations Screen (4) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Ideomotor Praxis Screen (4) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Proverb Interpretation (4) | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

CERAD=Consortium to Establish a Registry in Alzheimer's Disease;

t=10.0 p<.001; t=8.0, p<.001,

p=3.64, p<.05; p=3.92, p<.05

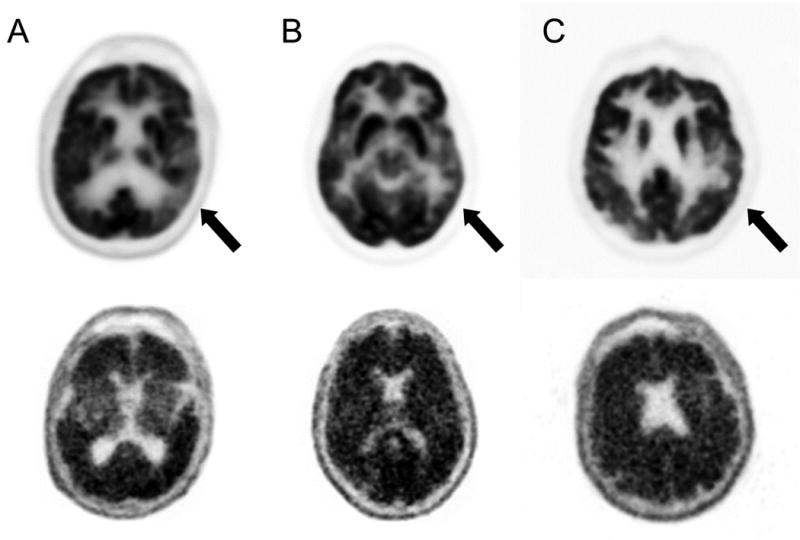

On fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET imaging, the LPA patients had mild left posterior temporoparietal hypometabolism (See Figure), whereas the AD patients had bilateral parietal hypometabolism (except for Patient D, whose FDG scan was normal). On florbetapir PET imaging, all six patients had diffusely positive scans with obscuration of the gray-white difference without localized differences.

Figure.

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging on the three patients (A,B, and C) with logopenic progressive aphasia. The top row are the fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scans. The areas indicate regions of hypometabolism. The bottom row are the corresponding [18F]florbetapir PET scans. Thear are positive for amyloid, as indicated by a reduction or loss of the normally distict gray-white matter contrast.

Discussion

This report illustrates the diagnostic value and practical application of amyloid neuroimaging with [18F]florbetapir in early-onset AD variants. The LPA patients had unilateral posterior temporoparietal hypometabolism on FDG-PET and diffusely positive florbetapir scans for amyloid pathology, indistinguishable from those in typical AD. Although lacking localizing value, the amyloid neuroimaging was able to confirm the suspicion of mild stages of early-onset AD in these patients.

LPA is usually a form of early-onset AD 1. LPA appears to result from a deficit in the phonological loop or short-term memory store for phonological memory traces due to asymmetric involvement of the left posterior temporoparietal cortex 2, 3, 7. However, there is still controversy over whether the clinical examination is specific or able to distinguish LPA, which primarily results from AD, compared to the other PPAs, which primarily result from FTLD 3. Moreover, LPA may progress rapidly losing its distinctiveness as it evolves to dementia 8. For these reasons, the early recognition of LPA is important if AD-related interventions are to be initiated early.

Amyloid imaging can define the preclinical and early stages of syndromes related to Alzheimer pathology. The most prominently studied amyloid imaging ligand is 11C-labeled PET tracer Pittsburgh compound B (PiB). This compound binds to fibrillar β-amyloid plaques on PET imaging and correlates with the presence of β-amyloid neuropathology. PiB has been a tremendous asset as a research tool, but its short half- life (about 20 minutes) requires an onsite cyclotron and is difficult to implement in most clinical settings. Compounds with longer half-lives, such as florbetapir, are more clinically useful. The FDA approved florbetapir in early 2012 for the clinical detection of amyloid deposition as an indicator of AD 9. An Alzheimer's Association task force with the Society of Nuclear Medicine made the following recommendations for the use of clinical amyloid neuroimaging 9: (1) patients with cognitive complaints and objectively confirmed impairment; (2) patients in whom diagnosis is uncertain (with AD being a possibility) after comprehensive evaluation by a dementia expert; and (3) the knowledge of amyloid beta status is expected to increase diagnostic certainty and alter management. All of these recommendations apply to the evaluation of patients with LPA.

Amyloid imaging may be particularly helpful in differentiating LPA from PPAs not due the Alzheimer neuropathology, but does not have localizing value (See Figure). Amyloid imaging shows significant discrimination between AD patients and normal controls; however, it does not help in localizing cognitive deficits and syndromes 10. As in our patients, other reports have not found focal amyloid signal on PET corresponding to focal FDG-PET hypometabolism, which is usually asymmetric left temporoparietal hypometabolism in LPA 10. Fibrillar β-amyloid deposition occurs early in AD, long before symptoms occur, and the clinical presence of LPA correlates with the presence of neurofibrillary tangles in the left temporoparietal region, rather than β-amyloid deposition7.

In conclusion, clinical florbetapir neuroimaging can help define early-onset AD variants, such as LPA, as due to Alzheimer pathology. This is a preliminary report, and there remain potential issues related to the reliability of florbetapir imaging and reading in the community. However, these patients illustrate how clinically-available amyloid imaging can be useful in the assessment of patients for AD. Future, more extensive research should help define the role of florbetapir imaging in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

National Institute on Aging R01 AG034499 [MFM].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mendez MF, Lee AS, Joshi A, Shapira JS. Nonamnestic presentations of early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27:413–420. doi: 10.1177/1533317512454711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76:1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman M. Primary progressive aphasia: clinicopathological correlations. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:88–97. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furst AJ, Kerchner GA. From Alois to Amyvid: seeing Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2012;79:1628–1629. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182662084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. 3rd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Josephs KA, Dickson DW, Murray ME, et al. Quantitative neurofibrillary tangle density and brain volumetric MRI analyses in Alzheimer's disease presenting as logopenic progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leyton CE, Hsieh S, Mioshi E, Hodges JR. Cognitive decline in logopenic aphasia: more than losing words. Neurology. 2013;80:897–903. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318285c15b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: a report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:e-1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehmann M, Ghosh PM, Madison C, et al. Diverging patterns of amyloid deposition and hypometabolism in clinical variants of probable Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2013;136:844–858. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]