CASE HISTORY

Dr. George Whipple first described the disease which bears his name in 1907.1 He described a 36-year-old male physician who presented with a 5-6 year history of insidious symptoms including cough, recurrent attacks of arthritis, gradual weight loss, and asthenia. By the end of his life, skin changes, diarrhea, abdominal swelling, and mesenteric adenopathy were prominent. Pathological examination showed macrophages and fat vacuoles in the small bowel and inflammation and macrophages within pleura, peritoneum and the aortic valve. Silver staining demonstrated rod-shaped structures. Electron microscopy has revealed that these aggregates consist of networks of membranous structures and bacillary bodies of the bacterium Tropheryma whipplei.2,3 Bacterial DNA sequencing and antibodies to T. whipplei may now be used to confirm the diagnosis.

We report a 49-year-old Caucasian man with a 4-year history of progressive cognitive and behavioral impairment, parkinsonism, cognitive fluctuation, altered sleep-wake cycles, myoclonus, visual hallucinations and subsequent death. His past medical history included hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoking, alcohol use, and cadaveric growth hormone replacement for delayed puberty as a child. There was no family history of dementia or movement disorder. He worked as a painter and was frequently exposed to solvents. He was in his usual state of health until approximately two years prior to initial evaluation. At that time, behavioral disturbances were noted by the family from whom he was estranged. He was described as depressed and severely withdrawn.

Approximately 12-16 months into his course, he became forgetful of recent events and conversations and repeated himself. He had increasingly odd behavior including sleeping during the day and being awake at night, wandering outside inappropriately dressed, and confabulating. His cognition fluctuated from staring spells to deep sleep from which he was difficult to arouse. At other times he was alert and fully oriented without recollection of prior events. He began to have well-formed visual hallucinations that he described as “brightly-colored pets” or “small people” and occurred during periods of lucidity. Eighteen months after onset, he was evaluated at an outside hospital for pneumonia, confusion and agitation. He had notable parkinsonism and myoclonus of the left upper extremity. Imaging and diagnostic studies were unrevealing. Valproic acid partially improved his myoclonic movements. He was also treated with intravenous thiamine given his prior alcohol use and presentation concerning for Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Small doses of risperidone and olanzapine produced generalized rigidity and drowsiness. He had one unexplained syncopal episode during his admission. Between episodes, he was alert and fully oriented and was discharged to a skilled nursing facility.

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) was considered due to rapid cognitive decline and a history of treatment with cadaveric growth hormone extract led to the suspicion of iatrogenic CJD. However, the absence of periodic sharp wave complexes (PSWCs) in the context of mildly left predominant intermittent generalized slowing,4 along with the lack of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) MRI findings,5 negative CSF testing for 14-3-3 protein (sensitivity: 85%), neuron-specific enolase (9 ng/mL; normal <20; sensitivity: 80%), and the relatively long ante-mortem course were not supportive of a prion disease.6-8

Six months later, he was transferred to Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, Missouri, for further investigation. The patient's instability had progressed and he developed recurrent falls. Gait was slow and shuffling with reduced arm swing, impaired postural reflexes, and en-bloc turning. He had reduced facial expressions, reduced blinking, and a monotonous hypophonic speech. He also had involuntary myoclonic movements of the left arm consisting of flexion at the elbow and adduction at the shoulder with or without flexion of the neck. Cranial nerve examination showed mild horizontal and vertical gaze apraxia. Oculomotor reflexes and spontaneous eye movements were intact. Rigidity was noted symmetrically in both arms and legs without truncal rigidity. Tremor was not evident. No abnormal movements were noted in the eyes, face, or palate. Aside from a poor appetite resulting in weight loss, a review of systems was unremarkable.

White blood cell counts (13.9 K/mm3), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (51 mm/h), and ferritin levels (505 ng/ml; normal range: 18-464 ng/ml) were mildly elevated. Laboratory studies indicated a non-megaloblastic anemia (mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 81.9 fl; hemoglobin 11.4 g/dl; hematocrit: 35.2%). A complete metabolic panel, B12 (444 pg/ml), methylmalonic acid (290 nmol/l, [normal range: 0-400 nmol/l]), homocysteine 9.3 μmol/l [normal range: 0-20 μmol/l]), folate (6.6 ng/ml [normal range: >4.1 ng/ml]), ammonia (57 μg/dl [normal range: 27-90 μg/dl]), and rheumatologic panel (antinuclear antibody (negative) and extractable nuclear antigen (negative)) were unremarkable. Bacterial and fungal cultures of blood and urine were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Toxoplasma gondii, Lyme serology, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL), and fluorescent treponemal antibody testing (FTA) were negative.9 Thyroid function, toxicology, and routine CSF testing were unremarkable (protein: 54 mg/dl [normal range: 15-45 mg/dl], glucose: 51 mg/dl [normal range: 40-70 mg/dl]; there were 6 nucleated cells, 95% lymphocytes, and cytology revealed lymphocytes and monocytes but malignant cells were absent). CSF viral serologies (HIV, herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1, HSV-2, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and varicella-zoster virus), gram stain and bacterial culture were negative. CSF protein 14-3-3, neuron-specific enolase, and immunoglobulin G (IgG) index were normal. CSF VDRL was negative. Anti-thyroperoxidase, anti-thyroglobulin, and anti-gliadin antibodies were not detectable. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal.

Brain MRI showed mild diffuse volume loss, and non-specific FLAIR hyperintensities involving the posterior body and splenium of the corpus callosum and subcortical white matter. No contrast-enhancing lesions were noted. The basal ganglia, thalamus, and medial temporal lobes were normal. DWI was unremarkable. Continuous video EEG monitoring showed generalized slowing with right parieto-occipital slowing, but no epileptiform discharges or PSWCs. Chest X-ray showed a persistent opacity in the left lower lobe. CT of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, and scrotal ultrasonography showed no evidence of malignancy. Whole body positron emission tomography (PET) was normal.

A course of IV methylprednisolone yielded no significant improvement. A trial of carbidopa-levodopa did not improve his parkinsonism. Myoclonic movements responded partially to sodium valproate. A history of smoking and presence of a persistent opacity on chest imaging led to a paraneoplastic syndrome being considered. Brain MRI in paraneoplastic encephalitis often shows evidence of medial temporal lobe involvement, and CSF abnormalities are detected in 80% of cases of paraneoplastic encephalitis.10 However, in this patient, imaging and laboratory evaluation showed no evidence of an occult malignancy or associated paraproteinemias. A paraneoplastic antibody screen was negative.

Following the exclusion of numerous infectious (viral, bacterial, spirochetal, fungal, and parasitic) etiologies, we considered the possibility of a steroid-responsive autoimmune encephalopathy associated with thyroiditis (e.g. Hashimoto's encephalopathy).10 Hashimoto's encephalopathy occurs most often in young females and is characterized by a fluctuating encephalopathy with behavioral changes. However, cases in older men and with gait disturbance, hallucinations, myoclonus, focal or generalized seizures, transient aphasia, and somnolence have also been described.11 Collagen vascular diseases, sarcoidosis, and celiac disease may also produce neuropsychiatric and extrapyramidal abnormalities. Given the absence of serum markers and the patient's poor response to corticosteroids these disorders were thought unlikely. The findings of progressive cognitive impairment with prominent cognitive fluctuations, frequent visual hallucinations, parkinsonism in the absence of other infectious, toxic, endocrine, or systemic causes of cognitive impairment led to a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). The presence of myoclonus, recurrent falls, syncope and possible neuroleptic sensitivity further supported this diagnosis. 12

Nine months following hospitalization, he had become completely dependent in all activities of daily living. Neurobehavioral exam showed a CDR of 3 (severe dementia), MMSE of 12/30 and a Short Blessed Test (SBT) score of 24/28. He scored 13/15 on the Boston Naming Test and 2/23 on the Wechsler Logical Memory Test (WLMS). Eight months later, the patient scored 11/30 on the MMSE, 25/30 on the SBT, 8/15 on the Boston Naming Test, and 0 on the WLMS. Eight months following this examination (nearly 4 years following disease onset) the patient died of sepsis, multi-organ failure, and inanition.

NEUROPATHOLOGY

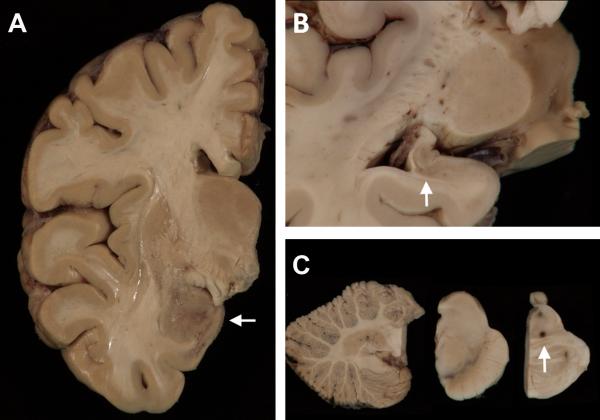

Consent was obtained for a brain-only autopsy in accordance with Institutional Review Board protocols. The unfixed brain weighed 1,350 g and had an unremarkable external surface with minimal atherosclerosis of the Circle of Willis. Coronal slices showed minimal generalized atrophy, mild atrophy of the amygdalae and hippocampi, and areas of discoloration and granularity were concentrated in the temporal lobes, amygdalae, hippocampi, putamena, and adjacent white matter (Fig. 1). Although there was a history of significant alcohol consumption, there was no evidence of Wernicke's encephalopathy. The substantia nigra and the locus coeruleus were well-pigmented.

FIGURE 1.

Macroscopy. (A) A coronal slice of the right hemibrain shows discoloration and granularity of the amygdala (arrow). A photomicrograph of the left hippocampus (B) shows diminished size and gray discoloration (arrow). (C) The cerebellum is unremarkable (left panel) and the substantia nigra (center panel) and locus coeruleus of the pons (right panel) show no significant pallor. There is an area of dark-brown discoloration at the junction of the tegmentum and basis pontis which corresponded to a nidus of bacteria-containing macrophages seen microscopically.

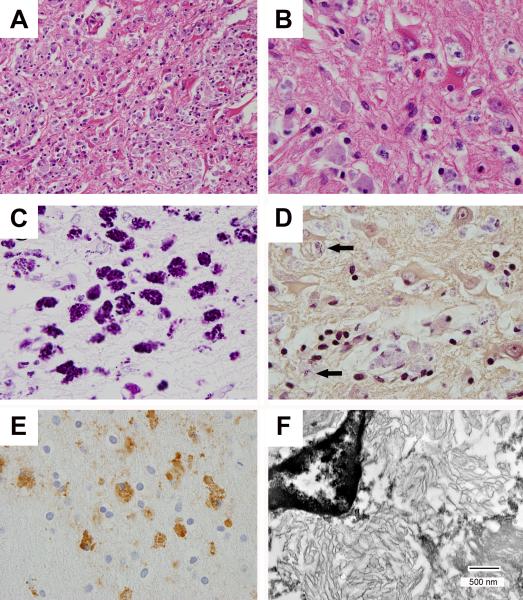

Sections of the hippocampi and amygdalae showed an inflammatory infiltrate containing monocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells and CD68-immunoreactive macrophages admixed with large atypical reactive astrocytes and residual neurons (Fig. 2). Basophilic aggregates were observed within the cytoplasm of macrophages. Associated parenchyma showed disruption, gliosis, and neuronal loss (Fig. 2). Changes were present in nearly all sections; however, the medial temporal lobes, bilateral amygdalae, and hippocampi were most involved. Microscopy showed no evidence of α-synuclein-positive neuronal inclusions (Lewy bodies or neurites), β–amyloid-immunoreactive diffuse or neuritic plaques, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, neurofibrillary tangles, tau-immunoreactive neurons, or TDP-43-immunoreactive neuronal or glial inclusions. After excluding viral, other bacterial, fungal, and protozoal infections, positive immunohistochemistry using bacterium-specific T. whipplei antibodies led to a final neuropathologic diagnosis of Whipple's disease encephalitis.

FIGURE 2.

Microscopy and fine structure of T. whipplei encephalitis. There is parenchymal disruption, reactive astrocytosis, and macrophages with basophilic staining of intracellular material (A, hematoxylin and eosin (HE) × 400; B, HE × 1,000), and a granular staining pattern with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain (C, × 1000). Gram stain shows predominantly pale blue staining of intracellular debris with occasional foci of strong gram-positivity (D, arrows: Gram stain × 1,000). Anti-T. whipplei antibodies highlight macrophages (E, T. whipplei immunohistochemistry × 1,000), and transmission electron microscopy reveals lamellar structures consistent with degraded bacteria (F, bar = 500 nm).

DISCUSSION

Diagnostic testing for WD may be challenging.13-20 Neurologic findings occur in up to one half of cases, and are most often reported late in the course of WD. However, rare cases have been reported in which neurologic manifestations occurred early or were the sole manifestation of disease. Neurologic manifestations are variable and include cognitive impairment, altered level of consciousness, psychiatric features, ataxia, seizures, myoclonus, supranuclear ophthalmoplegia, hypothalamic dysfunction, and sensory deficits. Oculomasticatory and oculofacial-skeletal myorhythmia, when present, are pathognomonic features; however, these are only seen in 20% of the cases. Other less common manifestations include proximal myopathy, myelopathy, stroke-like episodes, papilledema, headache, leptomeningeal inflammation, progressive deafness, and pyramidal or extrapyramidal disorders.

CSF analysis often reveals mildly elevated protein, mild pleocytosis, increased immunoglobulin production or oligoclonal bands, but may be completely normal, as with this patient. One CSF hallmark of CNS WD is the presence of histiocytes containing granular periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive cytoplasmic particles on cytologic analyses.

Although there are no specific imaging findings for CNS WD, brain MRI may show high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging involving the hypothalamus, optic chiasm, mammillary bodies, cerebral or cerebellar peduncles, medial temporal lobes and uncus. Lesions may exhibit restricted diffusion or gadolinium enhancement. EEG has been reported to show nonspecific slow wave activity and abolition of sleep-wake cycles. Stereotactic brain biopsy may be helpful in select cases, chiefly when other tests cannot exclude a treatable disease. In an attempt to improve diagnostic accuracy, guidelines for diagnostic screening and biopsy of WD were proposed in 1996 (Table 1). A diagnosis of definite CNS WD requires the presence of at least one of the following: positive tissue biopsy, positive PCR analysis, and OMM or OFSM. In the absence of all these three criteria, additional studies should be undertaken to confirm the diagnosis of possible CNS WD.

TABLE 1.

Diagnostic guidelines for CNS Whipple's disease*

|

Definite CNS WD |

| Must have 1 of the following 3 criteria: |

| Oculomasticatory myorhythmia (OMM) or oculofacial skeletal myorhythmia (OFSM) |

| Positive tissue biopsy |

| Positive PCR analysis |

|

Possible CNS WD |

| Must have 1 of 4 systemic symptoms, including: |

| Fever of unknown origin |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms (steatorrhea, chronic diarrhea, abdominal distention, pain) |

| Chronic migratory arthralgias or polyarthralgias |

| Unexplained lymphadenopathy, night sweats, or malaise |

| Must also have 1 of 4 unexplained neurological signs, including: |

| Supranuclear vertical gaze palsy |

| Rhythmic myoclonus |

| Dementia with psychiatric symptoms |

| Hypothalamic manifestations |

Adapted from [20].

This challenging case presented with several features that led to an ante-mortem diagnosis of DLB. Supportive features included the presence of myoclonus, repeated falls, fluctuating level of consciousness, syncope, and neuroleptic sensitivity. Although rapid forms of DLB have been described, these remain atypical with an average disease course of 5-7 years prior to death in most cases.21 Gaze apraxia is not a typical feature, but has previously been reported in DLB.22 While a rapidly progressive dementia with psychiatric features and myoclonus are recognized complications of CNS WD, other clinical features were not typical of this diagnosis. The absence of the typical movement disorders of CNS WD, along with the unremarkable information provided by CSF and MRI investigations, increased the diagnostic difficulties of this case. WD remains a challenging diagnosis despite improved diagnostic testing and may masquerade as a more frequent neurodegenerative disorder. A high index of suspicion for this disorder is needed in any patient presenting with a rapidly-progressive dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the patient and his family for their help. Written consent for publication was obtained from the next-of-kin. We thank Deborah Carter, Toral Patel, Lisa Taylor-Reinwald, and Karen Green for expert assistance. Support for this work was provided by grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (P50-AG05681, P01-AG03991), the Hope Center for Neurological Disorders, the Buchanan Fund, the Charles F. & Joanne Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation. A summary of these data were presented at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Association of Neuropathologists.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Interest

The authors, KH, RMT, MG, RES, and NJC declare no conflicts of interest.

N. Ghoshal has participated or is currently participating in clinical trials of anti-dementia drugs sponsored by Elan/Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Wyeth, Pfizer, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

T. L. S. Benzinger declares an interest as a consultant for Biomedical Systems, ICON Medical Imaging, Eli Lilly Advisory Board, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals.

D. B. Clifford serves on Data Safety Boards for Amgen, Biogen, GlaxoSmithKline, Millennium, Genzyme, Genentech, and Pfizer. He has been a consultant to Brinker, Biddle, Reath (Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML) Consortium), Genentech, Genzyme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Millennium, Biogen Idec, and Pfizer. He has received research support from the Alzheimer's Association, Biogen Idec, Eli Lilly, Roche and Pfizer. He has received speaking fees from Biogen, University of Kentucky, ECTRIMS, and CMSC/ACTRIMS.

J. C. Morris declares an interest as a consultant for: Eisai, Elan/Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Program, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer/Wyeth, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Merck, and Schering Plough; support form NIH/NIA; speaking fees: Dickinson address at Ohio Wesleyan, ABA Soriano Lectureship, Morrell Lecture (Chicago), Eisai (South Korea), Bial Neurology Forum (Portugal); royalties from: Blackwell Medical, Taylor and Francis.

J. E. Galvin serves on a scientific advisory board for the American Federation for Aging Research and on the Board of Directors and the Scientific Advisory Council for the Lewy Body Dementia Association; he serves on speakers’ bureaus for Pfizer Inc., Eisai Inc., Novartis, and Forest Laboratories, Inc.; has served as a consultant for Novartis, Forest Laboratories, Inc., Pfizer Inc, Eisai Inc., Janssen, and Medivation, Inc.; he has received license fee payments for AD8 dementia screening test (copyrighted): license agreements between Washington University and Pfizer Inc, Eisai Inc., and Novartis; and receives research support from Novartis, Eli Lilly and Company, Elan Corporation, Wyeth, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the NIH/NIA, and the Alzheimer Association.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERNCES

- 1.Whipple GH. A hitherto undescribed disease characterized anatomically by deposits of fat and fatty acids in the intestinal and mesenteric lymphatic tissues. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1907;18:382–393. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raoult D, Birg ML, La Scola B, et al. Cultivation of the bacillus of Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:620–625. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Scola B, Fenollar F, Fournier PE, Altwegg M, Mallet MN, Raoult D. Description of Tropheryma whipplei gen. nov., sp nov., the Whipple's disease bacillus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:1471–1479. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-4-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins SJ, Sanchez-Juan P, Masters CL, et al. Determinants of diagnostic investigation sensitivities across the clinical spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2006;129:2278–2287. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitali P, Maccagnano E, Caverzasi E, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI hyperintensity patterns differentiate CJD from other rapid dementias. Neurology. 2011;76:1711–1719. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821a4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geschwind MD, Josephs KA, Parisi JE, Keegan BM. A 54-year-old man with slowness of movement and confusion. Neurology. 2007;69:1881–1887. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000290370.14036.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young GS, Geschwind MD, Fischbein NJ, et al. Diffusion-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1551–1562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, et al. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2009;132:2659–2668. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGinnis SM. Infectious causes of rapidly progressive dementia. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:266–285. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawn ND, Westmoreland BF, Kiely MJ, Lennon VA, Vernino S. Clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalographic findings in paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2003;78:1363–1368. doi: 10.4065/78.11.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mocellin R, Walterfang M, Veakoulis D. Hashimoto's encephalopathy: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:799–811. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies - Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fenollar F, Puechal X, Raoult D. Medical progress: Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:55–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamed W, Neil E, Kupsky WJ, et al. Isolated inctracranial Whipple's disease: report of a rare case and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2011;308:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moos V, Schneider T. Changing paradigms in Whipple's disease and infection with Tropheryma whipplei. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:1151–1158. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black DF, Aksamit AJ, Morris JM. MR imaging of central nervous system Whipple disease: a 15-year review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1493–1497. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donmez FY, Ulu EMK, Basaran C, et al. MRI of recurrent isolated cerebral Whipple's disease. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010;16:112–115. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.1830-08.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Voderholzer U, Riemann D, Gann H, et al. Transient total sleep loss in cerebral Whipple's disease: a longitudinal study. J Sleep Res. 2002;11:321–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren JD, Schott JM, Fox NC, et al. Brain biopsy in dementia. Brain. 2005;128:2016–2025. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louis ED, Lynch T, Kaufmann P, Fahn S, Odel J. Diagnostic guidelines in central nervous system Whipple's disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:561–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarawneh R, Galvin JE. Distinguishing Lewy body dementias from Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:1499–1516. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.11.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clerici F, Ratti PL, Pomati S, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies with supranuclear gaze palsy: a matter of diagnosis. Neurol Sci. 2005;26:358–361. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]