Acute Pancreatitis (AP), an acute inflammatory disorder of the pancreas, usually runs a mild clinical course. A subset of patients develops severe disease independent of the degree of initial insult or etiology, with high morbidity, and mortality up to 45%1. Most scoring systems to assess disease severity (e.g. hematocrit, APACHE-II) capture local or systemic effects of pancreatic injury and are generally similar in their predictive ability when tested in the same cohort of AP patients2.

In 1992, a clinically based Atlanta classification was proposed that stratified AP patients into mild and severe categories3. Severe AP was defined broadly by fulfillment of either clinical scoring system criteria (Ranson's, APACHE-II), or presence of local or systemic complications. Wide adoption of this classification led to high variability in reporting of data which was difficult to compare across centers. Moreover, suggested definitions for local complications were ambiguous. Advances since then have identified persistent organ failure (OF) and pancreatic necrosis (infected) as key determinants of mortality, and local complications are now better characterized. Recognizing limitations of the Atlanta classification, two new classifications: Revision of the Atlanta Classification (RAC)4 and Determinant Based Classification (DBC)5 were recently published.

The RAC4 is broader than DBC in scope; in addition to severity classification, it provides a clear definition for diagnosing AP, highlights onset of pain as an important reference point, defines interstitial and necrotizing pancreatitis, and the individual local complications. RAC outlines early and late phases of the disease, with the late phase typically limited to patients with moderate or severe disease. Severe AP is defined solely by the presence of persistent OF. Local complications are associated with morbidity, whereas persistent OF is the main determinant of mortality. OF is proposed to reflect the systemic effects of pancreatic injury, and, although often present with local complications, it may occur independently.

The DBC5 uses two main determinants of mortality in AP, i.e. persistent OF (systemic) and infected (peri)pancreatic necrosis (local) to classify patients into four categories. It does not recognize the two phases (i.e. early and late) and operates on the premise that either event may occur at any stage of disease. For accurate classification of severity, determination of necrosis is needed, and, necrosis is presumed to be sterile until infection is proven by imaging or direct documentation.

Falling into severe RAC or DBC category is usually apparent within the first week (OF that becomes persistent) but can be delayed (e.g. development of persistent OF at the onset of infected necrosis). DBC is also dynamic with respect to the status of infection in necrosis (e.g. a patient with presumed sterile necrosis without persistent OF may transition from moderate to severe category by documentation of infected necrosis, or into critical category if persistent OF also ensues). The DBC critical category represents a subset of patients in the severe RAC category and includes the sickest AP patients. This subgroup, therefore, is expected to have the highest morbidity and mortality.

Two recent studies have independently validated the RAC6 and DBC7. The report by Acevedo-Piedra et al in this issue of the journal8 evaluates performance of the original Atlanta classification, RAC and DBC in the same cohort of AP patients. The authors retrospectively applied these classification systems to 543 episodes of AP in 459 adult patients admitted to their institution during a five year period. All imaging (primarily CT scans) were reviewed by a radiologist who was aware of the timing of imaging but not of the clinical data or severity classification. Patients not meeting the criteria for obtaining a CT scan and a mild clinical course were presumed to have no local complications.

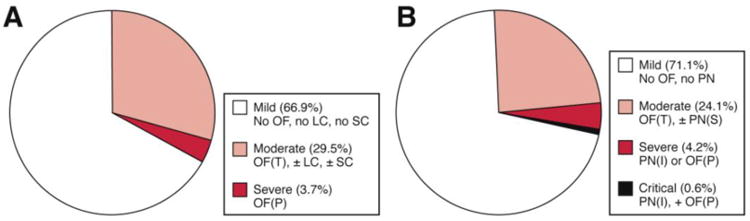

Not surprisingly, both RAC and DBC were superior to the original Atlanta classification in all outcome measures. No significant differences in the distribution of severity categories or outcomes, however, were noted between RAC and DBC categories. Being a community based cohort (only 4 patients were referred), the majority of patients were classified as having mild disease by either classification (about two-thirds) with little morbidity and no mortality (Figure 1). Patients in the moderate categories had higher morbidity and longer length of stay but no mortality. Only a small fraction of patients (∼5%) were classified into severe or severe/critical categories with highest morbidity and all mortality. While 2/3 (66.7%) patients with critical AP died, 14/23 (60.9%) in the severe DBC category also died during hospitalization.

Figure 1.

Distribution of severity categories in Acevedo-Piedra et al study8 - (A) Revision of the Atlanta Classification (RAC); (B) Determinant Based Classification (DBC).

Due to small number of patients in severe and critical categories, the lack of statistical significance for subgroup comparisons between RAC and DBC categories in the Acevedo-Piedra et al study8 is expected. For example, using 40% prevalence of an outcome, a sample size of roughly 90 and 375 patients in each group is needed to detect a 20% or 10% reduction in outcome, respectively, with a power of 80% and an α of 0.05. Except for mortality, other outcomes in the severe RAC and DBC categories were virtually similar. Though sample size of the critical category was very small to provide meaningful estimates, outcomes in this group were poor. Data from our institution, which represents a tertiary care cohort with a higher fraction of patients (but overall small numbers) in severe and critical categories, show similar results (In Press: Am J Gastroenterol). Therefore, collaborative effort of multiple centers is needed to achieve sample sizes for appropriate subgroup comparisons (between or within subpopulations of moderate and severe categories). Extrapolation of data from the Acevedo-Piedra et al study8 to a larger population (e.g. the annual number of AP cases in the US)9 provides a broader context of the expected number of patients and individual outcomes. Proportionally, patients in the mild category form the bulk of hospital admissions and moderate category accounts for most number of patients requiring nutritional support and/or intervention.

With the publication of RAC and DBC, clinicians and researchers may wonder which classification to use in their practice or which one may better answer research questions. Although RAC and DBC may differ conceptually, differences between them are few (Table 1 shows discordance between classifications). DBC appears to expand the scope of the RAC further by creating severity categories based on the primary determinants of mortality in AP that closely matches the implicit basis of RAC. Mild and moderate RAC and DBC categories are virtually identical, and, the critical DBC category represents a subset of severe RAC patients who have both persistent OF and infected necrosis.

Table 1.

Discordance between Revision of the Atlanta Classification (RAC) and Determinant Based Classification (DBC) severity categories.

| RAC category | DBC category | |

|---|---|---|

| Exacerbation of co-morbid disease | Moderate | Not classified |

| Acute peripancreatic fluid collection or pseudocyst | Moderate | Mild |

| OF (P) not present; PN (I) present | Moderate | Severe |

| OF (P) present; PN (I) present | Severe | Critical |

OF, organ failure; PN, pancreatic necrosis; OF (P), persistent organ failure; PN (I), infected pancreatic necrosis.

RAC is more relevant to the day-to-day clinical care of patients. Classifying patients into categories is simpler with RAC than DBC as it is not dependent on (early) CECT (contrast-enhanced computed tomography) (which is difficult to perform with existing or new renal failure or insufficiency and with contrast allergy) or the status of infection in necrosis to determine disease severity. There is a universal acceptance of delaying interventions (such as necrosectomy) in severe AP patients for as long as possible (∼4 or more weeks)10. Therefore, treatment of severe AP in the initial period focuses on aggressive resuscitation, treatment for organ failure and nutritional support. Detailed characterization of the nature of local complications (e.g. walled-off necrosis) becomes important later to predict the natural course of disease and to plan an intervention. Clinicians need to be aware that patients in the moderate category of RAC are a heterogenous group who will often need nutritional support and/or interventions based on the type of local complications present. Patients with persistent OF, and especially those with persistent OF and infected necrosis will have the highest morbidity and mortality.

The proposal of using Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) in addition to OF makes RAC more suitable for allocating patients into prospective randomized trials (e.g. fluid resuscitation, medication to reduce severity) in the first week of their illness. Except for mild and critical categories, patients in other categories consist of subpopulations with varying outcomes. After the first week, definitions of local complications proposed in the classifications can guide patient assignment into intervention studies. In addition to information on the details of OF (any; transient or persistent; single or multiorgan; organ type; timing) and pancreatic necrosis (yes or no; infected or not), observational studies and disease registries should record and report data on the frequency of and outcomes within subgroup of patients in the moderate AP (acute peripancreatic fluid collection, necrosis type [pancreas only, peripancreatic, both], exacerbation of co-morbid disease) and severe AP (persistent OF with/without necrosis) categories to allow for future comparisons.

Experts who developed RAC and DBC need to be congratulated -- these classifications are major advances in the standardizing the terminology during the natural course of AP. Using the nomenclature will allow for comparison among centers, allocation of patients into randomized trials, and planned or post hoc analyses of observational data and registries depending on the research question, disease stage, and nature of local complication. This approach will advance the field further and provide empiric data to personalize care for AP patients.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Yadav is supported in part by NIH - RO1DK 077906.

The author reviewed versions of the manuscript on the Revision of the Atlanta Classification during preparation and is acknowledged in the document.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author reports no conflicts relevant to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Petrov MS, Shanbhag S, Chakraborty M, et al. Organ failure and infection of pancreaticnecrosis as determinants of mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:813–20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mounzer R, Langmead CJ, Wu BU, et al. Comparison of existing clinical scoring systems to predict persistent organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1476–82. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.005. quiz e15-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley EL., 3rd A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis,Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586–90. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170122019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–11. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger EP, Forsmark CE, Layer P, et al. Determinant-based classification of acute pancreatitis severity: an international multidisciplinary consultation. Ann Surg. 2012;256:875–80. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318256f778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talukdar R, Clemens M, Vege SS. Moderately severe acute pancreatitis: prospective validation of this new subgroup of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41:306–9. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318229794e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thandassery RB, Yadav TD, Dutta U, et al. Prospective validation of 4-category classification of acute pancreatitis severity. Pancreas. 2013;42:392–6. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182730d19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acevedo-Piedra NG, M-H N, Rey-Riveiro M, et al. New classifications of acute pancreatitis: validation of Determinant-based and Revision of the Atlanta Classification. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179–87. e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Brunschot S, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, et al. Treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]