Abstract

Objectives

The study objectives were to describe and compare causes of, and activities during, postpartum parents’ nocturnal awakenings.

Methods

Twenty-one primiparous postpartum couples were studied for one week with qualitative and quantitative methods.

Results

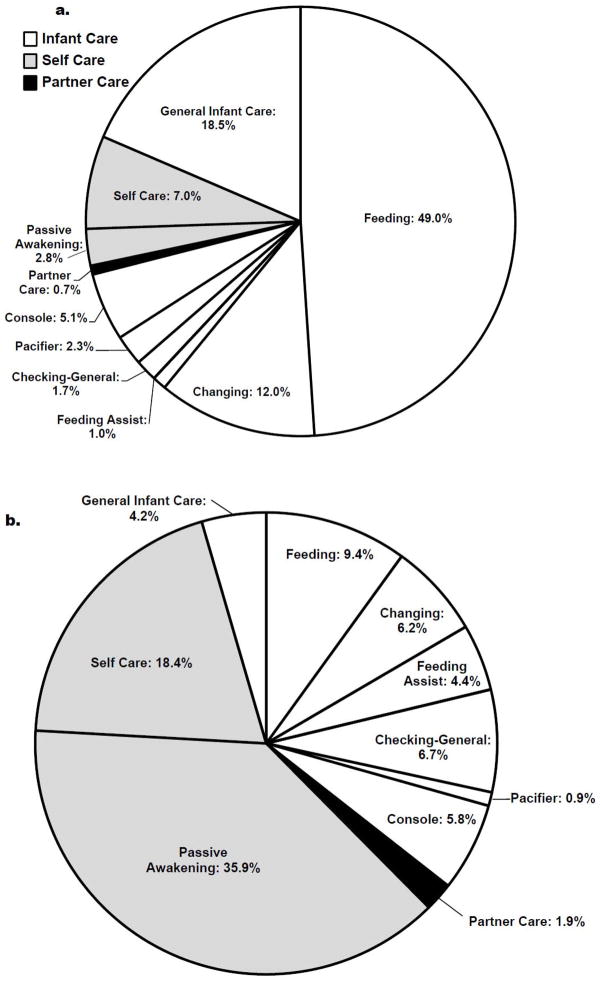

Mothers reported more awakenings per night (3.3±1.1) and more wake after sleep onset (116.0±60.0 minutes) compared to fathers (2.4±0.5 and 42.7±39.4 minutes, respectively). ‘Actions taken’ during maternal nocturnal awakenings were primarily for infant feeding (49.0%), general infant care (18.5%), and infant changing (12.0%). ‘Actions taken’ during paternal nocturnal awakenings were primarily ‘passive awakenings’ (35.9%), for self-care (18.4%), and for infant feeding (9.4%).

Conclusions

Qualitative analyses revealed ways that new families can optimize the sleep of both parents’ while also providing optimal nocturnal infant care.

Keywords: maternal, paternal, family, sleep, child care

INTRODUCTION

Sleep is a vital behavior that impacts all facets of life. Sleep disturbance adversely affects daily functions that include general health (Alvarez & Ayas, 2004), hormone regulation (Copinschi, 2005), neurocognitive performance (Goel, Rao, Durmer, & Dinges, 2009), decision making (Harrison & Horne, 2000), and mood (Bonnet, 1986). Sleep disturbance among postpartum parents is becoming better understood (Gay, Lee, & Lee, 2004; Kennedy, Gardiner, Gay, & Lee, 2007; Montgomery-Downs, Insana, Clegg-Kraynok, & Mancini, 2010), and is primarily caused by infant signaling for nocturnal caregiving needs (Nishihara, Horiuchi, Eto, & Uchida, 2002). New parents are responsible for providing infant care, adjusting to parenthood, and meeting societal and financial demands all while facing the challenges of disturbed sleep.

The postpartum family is a system whereby one members’ experience can affect the experiences of other family members. This process is particularly relevant to sleep experienced among postpartum parents. Whereby, nocturnal experiences between mothers and fathers, and infants and parents, bidirectionally interact as dynamic transactional processes (Nishihara et al., 2002; Meijer & van den Wittenboer, 2007 [see review, Sadeh, Tikotzky, & Scher, 2010]). These processes are further compounded by the intersection of infant and parental physiological needs (e.g., feeding and rest, Rowe, 2003), and the actions taken to address those needs. These processes are encompassed within the Integrative Mid-Range Theory of Postpartum Family Development; according to this theoretical orientation, during the first eight postpartum weeks parents are influenced by new physical, psychosocial, and environmental factors that direct their focus toward “surviving and thriving” (i.e., learning ways to manage their new workload and family wellbeing [p. 41; Christie, Poulton, & Bunting, 2007]). Understanding postpartum parents’ nocturnal experiences and caregiving activities is central to the development of strategies that can be used to optimize parental sleep, nocturnal infant care, and family wellbeing.

In a recent study of the relations between infant sleep and parental involvement, Tikotzky and colleagues reported that mothers were more involved with night time infant caregiving compared to fathers (Tikotzky, Sadeh, & Glickman-Gavrieli, 2011), which is consistent with previous reports (Ball, Hooker, & Kelly, 2000; Goodlin-Jones, Burnham, Gaylor, & Anders, 2001). Notably, other reports emphasize the strides that fathers have made in their involvement in children’s daily care over recent decades (Coleman & Garfield, 2004). For instance, time-diary studies have shown that U.S. fathers increased time spent on child care duties from 2.5 hours per week in 1965 to 7 hours per week in 2000, an amount greater than fathers in Australia, Canada, France, Britain, and Holland (Bianchi, 2006). However, an examination of specific nocturnal experiences and caregiving activities among postpartum parents has yet to be reported. The study objective was to describe and compare what happens during mothers’ and fathers’ nocturnal awakenings during the early postpartum period. To achieve this objective we used an ecologically valid field-based mixed-methods approach using both qualitative and quantitative data.

METHODS

The current study is an analysis of data from a convenience sample that was collected for a descriptive study of normative postpartum sleep (Montgomery-Downs et al., 2010). The current study was approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board; participants provided informed consent and Health Information Portability and Accountability Act authorization.

Participants

Women and their partners were recruited from a larger study of normative maternal postpartum sleep (Montgomery-Downs et al., 2010). Couples were excluded from the study on the basis of maternal history of major depressive or anxiety disorder, a score ≥ 16 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression (Radloff, 1977), or if either partner in the couple was diagnosed with a sleep disorder. Couples were also excluded if the mother was pregnant with multiples, had a preterm delivery, or if the infant was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. Infants were born 39.61 (SD = 1.09) weeks gestation, and were 6.93 (SD = 1.26) weeks old during the study. Infants were primarily breast fed (61.90%), 14.29% were formula fed, and 23.81% were both breast and formula fed. Family characteristics are indicated on Table 1.

Table 1.

Family Characteristics

| Total (N = 42) | Mothers (N = 21) | Fathers (N = 21) | Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t | (df) | p |

| Age | 27.94 | 5.03 | 26.81 | 4.80 | 29.08 | 5.11 | −2.24 | (20) | .04 |

| Education | 15.5 | 3.58 | 15.29 | 3.47 | 15.71 | 3.76 | −.89 | (20) | .38 |

| Income | $56,091 | $34,320 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Time Knowing Each other | 6.67 | 4.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Time Dating | 5.40 | 4.27 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Time Cohabitating | 4.17 | 3.17 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Time Married | 3.33 | 1.66 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total (N = 42) | Mothers (N = 21) | Fathers (N = 21) | Difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p |

| Cohabitating | 42 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Married | 30 | 71.43 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| White | 39 | 92.86 | 19 | 90.48 | 20 | 95.24 | 1.09 | .30 |

| Black | 1 | 2.38 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.76 | 3.62 | .06 |

| Other | 2 | 4.76 | 2 | 9.52 | 0 | 0 | 8.46 | .004 |

| Work Status: Family leave | 13 | 30.95 | 12 | 57.14 | 1 | 4.76 | 62.42 | < .0001 |

| Work Status: Fulltime | 16 | 38.10 | 1 | 4.76 | 15 | 71.43 | 91.82 | < .0001 |

| Work Status: Part-time | 6 | 14.29 | 2 | 9.52 | 4 | 19.05 | 3.03 | .08 |

| Work Status: Unemployed | 7 | 16.67 | 6 | 28.57 | 1 | 4.76 | 18.91 | < .0001 |

Note. Variables were reported for status at time of study. Education, and “Time” knowing, dating, cohabitating, and married are represented in years.

Procedure

Participants completed the research protocol for eight continuous days within the range of their third and eighth postpartum weeks. Demographic variables were obtained at study entry. Customized software for a Palm Zire 72 personal digital assistant (PDA) was used for this study (Bruner Consulting Co., Longmont, Colorado). Each morning within two hours after awakening parents used a PDA to impute values for their previous nights; 1) nocturnal awakening frequency, and 2) cumulative minutes of nocturnal wake. When compared to the gold standard of polysomnography, ones’ subjective report of sleep is considered acceptable (kappa = .87, sensitivity = 92.3%, specificity = 95.6% [Rogers, Caruso, & Aldrich, 1993]). Participants also used the PDA voice memo function to respond to the request, “Please describe why you woke up and what you did each time you woke up last night.” PDA data were downloaded at the West Virginia University Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research Laboratory at the end of each study week.

Qualitative and Quantitative analyses

Mixed qualitative and quantitative methods were used to analyze all available data. Qualitatively, each of the daily verbal recordings were transcribed verbatim, and a coding structure was developed by the research team using an integrative approach of inductive and deductive organizing frameworks in order to arrive at the conceptual codes and subcodes (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007; Sofaer, 1999). Codes and the coding structure were continually discussed by the research team until the point of theoretical saturation (Glaser, 1967; Patton, 2002). Then two investigators coded each transcript separately. These codes gave way to themes reported below. All coding discrepancies were reconciled by the researchers.

The portion of the statement that probed “…why you woke up…” provided information about the ‘wake trigger.’ ‘Wake triggers’ were separated according to the following assessment codes; awakening due to infant (e.g., “When I woke up it was because he was crying…”), awakening not due to infant (e.g., “I woke one time to go to the bathroom.”), and awakening undifferentiated (e.g., “I woke up four times last night at 2:00, 3:00, 5:00, and 6:00…”).

The portion of the statement that probed “…what you did each time you woke up last night.” provided information about the ‘action taken.’ ‘Actions taken’ were separated into assessment codes listed in the first column in Table 2.

Table 2.

Awakening “Action taken” codes and representative qualitative excerpts for mother and father participants

| Action Taken | Mother Reports | Father Reports |

|---|---|---|

| Changing Infant | “Last night I woke up four times, first time change the diaper use the bathroom and feed the baby, second time was to feed the baby, third time was to change the baby and feed her, and the fourth time was to feed her.” | “I woke up once last night and that was to change a diaper at the beginning of the night.” |

| Checking on Infant | “Last night I woke up about five times, one time to check on the baby then the rest were because she was hungry or needed changed.” | “Woke up three times last night, twice to check on wife and baby and one time to use the restroom.” |

| Consoling Infant | “The first two times I woke up were to put him back to sleep cause he woke up wasn’t fussy it didn’t take long the third time I woke up he was really upset and I had to stay awake with him for a long time.” | “I woke up one time last night [Mother] woke me up a little bit after I went to bed because the baby wouldn’t sleep and was fussing so I went over and rocked him and patted his bum until he fell asleep and that only took ten minutes then I put him back to sleep and he slept soundly until this morning.” |

| Feeding Infant | “I woke up about six times last night. First time he was crying for food I fed him. Second time he was hungry too, I fed him. Third time I think I thought he was hungry but when I got up just gave him passy and went back to bed lasted for ten minutes, maybe. I got back up, fed him, went back to sleep, then the next time I woke up and I told [Husband] to go in and hang out with the baby and feed him. Then the next time I woke up to feed him” | “Last night I woke up twice. Once was to feed the baby and the second time my wife fed the baby, and when I finally got up I took the baby downstairs so my wife could get some sleep, and I was up until later on and fell asleep..” |

| Assist Feeding Infant | “I woke up three times last night two times were to feed the baby and one time was to pump food for the baby for the next day.” | “I woke approx 3 times each time because the baby was crying and needed fed, I fed once my wife fed twice. Both times I woke fully and helped her to burp the baby whenever she fed.” |

| General Infant Care | “I woke up last night twice for about 30 minutes to tend to the baby.” | “I woke up twice during the night to take care of [Baby] for a total of about one hour.” |

| Attending to Pacifier | “The first 2 times I got up last night were to put his pacifier back in.” | “I got up once to go to the restroom and give the kid his passy and I think I may have woke up another time, can’t remember.” |

| Passive Awakening | “I woke up three times last night the first time I didn’t get up I just woke up when [Father] got out of bed the other two times I got up both times to take care of the baby.” | “I woke up around 2:15 for no reason. I woke up at 3:30 because [Mother] was feeding baby, at 4:45 because dog woke me up, and 7:45 because time to wake up.” |

| Partner Care | “Last night I woke up three times. First time changed the baby used the bathroom and feed her. Second time was to feed the baby and the third time was to get [Father] up for work, and use the bathroom and feed the baby.” | “Last night I woke up about three times listening to the baby scream, then I tried to comfort my wife and went back to sleep.” |

| Self Care | “I woke up because I was thirsty, I woke up to use the restroom, and I woke up to feed the baby three times.” | “I woke up like five times last night, two were to use the bathroom and the other three were because of the baby.” |

Note. Participant transcripts were independently examined by all three investigators to identify the most representative transcript, for mothers and fathers separately, for each ‘action taken’ category. Investigators convened to reach 100% consensus on the most representative transcripts for each ‘action taken’ category for both mothers and fathers.

After verbal transcripts were coded for ‘action taken,’ a within subject quantitative analysis was calculated to describe the percentage occurrence of each coded action throughout the assessment period. Specifically, within each participant the frequency of each ‘action taken’ code (numerator) was standardized by the number of actions that were coded for the entire assessment week (denominator) and were then converted to a percentage. Within participant percentages of each ‘action taken’ were averaged across all mothers and across all fathers, separately.

The averaged ‘action taken’ codes were then grouped according to ‘infant care’ (e.g., feeding, changing) ‘self care’ (e.g., passive awakening, self care), and ‘partner care’ (e.g., partner care). A χ2 analysis was calculated on these ‘action taken’ groups, as well as demographic variables, between mothers and fathers. Quantitative data that were collected from the PDA included nocturnal awakening frequency, and cumulative minutes of nocturnal wake. Paired sample t-tests and Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated to compare these data, as well as demographic variables, between mothers and fathers (Cohen, 1988).

Missing data and preliminary analyses

Across the eight-day assessment period, all participants (N = 42) provided morning value entries for nocturnal wake frequency, and all participants except for one father (due to protocol non-adherence) provided morning value entries for minutes of nocturnal wake. Mothers provided M = 7.3 (SD = 1.1), and fathers provided M = 7.0 (SD = 1.2) days of morning value entries.

Across the eight-day assessment period, three mothers and four fathers from separate couples did not provide any morning voice recordings due to protocol non-adherence. Mothers who did not provide voice recordings obtained less education than mothers who did provide voice recordings (M = 11.0 ± 1.7 years; M = 16.0 ± 3.2 years, respectively), t(1, 19) = 2.6, p = .02. Mothers and fathers who did and did not provide voice recordings did not differ on any other demographic variable. Among mothers and fathers who did provide morning voice recording data (N = 35, n = 18 mothers, and n = 17 fathers), they contributed M = 5.8 (SD = 2.2) and M = 4.9 (SD = 2.2) days of recordings, respectively. The number of morning voice recordings were not associated with participant age, infant age, household income, or education; however, mothers’ voice recording frequency was negatively associated with education (r = −.51, p = .02). Participants’ voice recording frequency did not differ by their own or their partner’s work status.

RESULTS

Nocturnal Wake: Frequency and Length

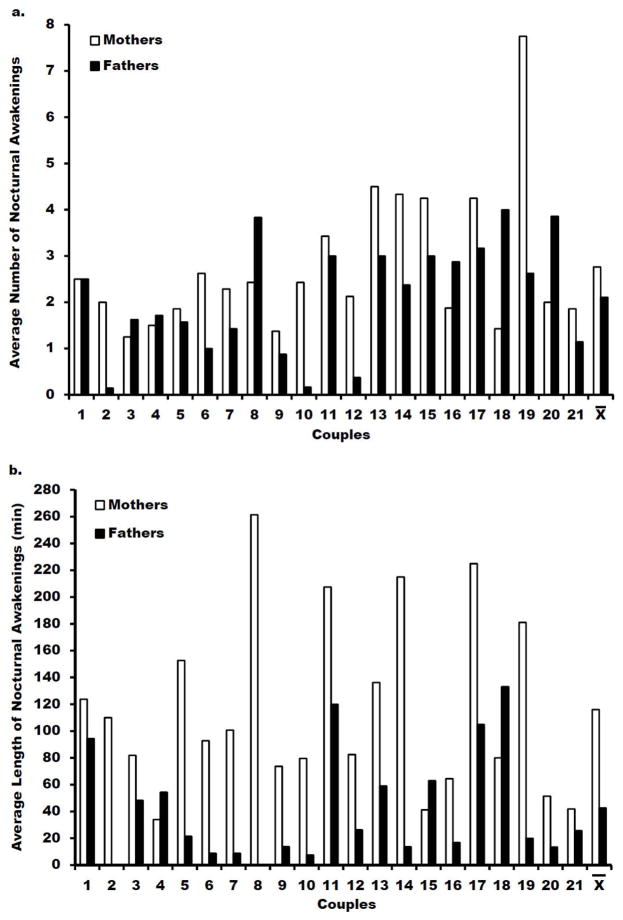

Mothers reported more nocturnal awakenings per night (2.9 ± 1.5) compared to fathers (2.1 ± 1.2); t(1, 20) = 2.1, p = .050, d = .60 (Figure 2a). Mothers’ nocturnal awakenings were more frequently infant triggered (65.2%) compared to fathers (25.5%); χ2 (1) = 30.4, p < .0001, Cramer’s V = .40. Whereas, fathers’ nocturnal awakenings were more frequently not infant triggered (55.4%) compared to mothers (20.5%); χ2 (1) = 24.63, p < .0001, Cramer’s V = .36. Mothers and fathers did not differ in their frequency of nocturnal awakenings where the wake triggers were undifferentiated (14.3% and 19.1%, respectively [p = .50]). Mothers reported more cumulative minutes of nocturnal wake after sleep onset (108.8 ± 59.5 minutes) compared to fathers (42.7 ± 40.8 minutes); t(1, 19) = 4.8 p < .001, d = 1.30 (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Mother and father dyads’ reported average nocturnal awakening frequencies (b) Mother and father dyads’ reported average nocturnal wake time after falling asleep.

(a) Within each couple, Mothers are on the left and Fathers are on the right. Parents entered values into the PDA. (b) Father from dyad # 2 reported not being awake for any period of time throughout the week. Father from dyad # 8 is missing his length of nocturnal awakenings report due to protocol non-adherence.

Nocturnal Wake: Qualitative Description and Synthesis

To take full advantage of the richness of the qualitative data, representative voice recordings that correspond to each assessment code are indicated in Table 2. Among mothers, ‘actions taken’ during nocturnal awakenings were primarily infant feeding, general infant care, and infant changing, respectively (Figure 1a). Among fathers, ‘actions taken’ during nocturnal awakenings were primarily passive awakenings, self care, and infant feeding, respectively (Figure 1b). The three ‘action taken’ code group percentages for mothers and fathers (‘infant care’ [89.5%; 43.8%], ‘self care’ [9.8%; 54.3%], and ‘partner care’ [0.7%; 1.9%], respectively) significantly differed; χ2 (2) = 47.3, p < .0001, Cramer’s V = .49. Mothers performed proportionally more ‘infant care’ than fathers; whereas, fathers performed proportionally more ‘self care’ and ‘partner care’ than mothers (see Figure 1a and b).

Figure 1.

Mothers’ (a) and fathers’ (b) reported ‘actions taken’ during their nocturnal wake

Values represent the proportion of each type of ‘action taken’ out of all reported actions. ‘Action[s] taken’ were identified according to the established qualitative assessment codes and grouped by ‘infant care’ ‘self care’ and ‘partner care’ for quantitative analyses.

Beyond specific infant caregiving activities, parental reports of nocturnal wake resulted in three general observations. First, parents fulfill multiple roles throughout their daily lives, which carryover into their nocturnal caregiving responsibilities. For instance, a mother reported how her daytime caregiving activities influenced her nocturnal caregiving experience, “I got up once last night to feed the baby, was then really tired because I got to bed late because it took me an hour and a half to get the baby to fall asleep last night.” Similarly, a father reported how the demands of his daily obligations influenced his lack of nocturnal caregiving, “I did not wake up any last night, got off work went right to sleep, woke back up, did this thing [study PDA recording].” Second, postpartum parents can have their own nocturnal caregiving needs. A mothers’ nocturnal caregiving need could be physiological, “I woke up last night several times because I needed to breast feed and I had to pump because we went on a date and I had extra milk from not feeding him.” A fathers’ nocturnal caregiving need could be to assure household safety and optimal family care, “Woke up three times last night, twice to check on wife and baby and one time to use the restroom.” Third, a parents’ nocturnal experience can be influenced by their partner. A mother reported, “I was awake three times last night twice to feed [Baby], then the third time was because my husband elbowed me in the head.” A father reported, “I think [Mother] woke me up a couple times to tell me the baby was having trouble sleeping.” In sum, although mothers and fathers may differ in their specific nocturnal caregiving functions, each parent is part of a family system whose nocturnal experience is influenced by their infant’s caregiving needs, their own daytime activities, their own caregiving needs, and their partner’s nocturnal experience.

Results indicate that mothers engage in the majority of nocturnal infant caregiving. Observations of parents’ reports provide insight into possible ways for parents to strategize a more balanced approach to nocturnal infant caregiving. First, mothers could more freely relinquish nocturnal caregiving responsibilities to fathers. For example, an instance of a mother who did not fully relinquish her nocturnal caregiving responsibilities to her partner is demonstrated by her report, “…the 2nd time I woke up because it was my husband’s turn to feed and change the baby, but I stayed up anyway.” Alternatively, an instance of a mother who did relinquish nocturnal caregiving (and acquired her needed rest) is demonstrated by her report, “I didn’t get up at all with the baby last night because [Father] attended to him because I had to get up early this morning.” This mother likely acquired more consolidated sleep (a necessary component for restorative sleep [Bonnet, 1986]) by relinquishing nocturnal caregiving, and thereby becoming more prepared for her early morning obligation. Second, fathers could initiate more active involvement in conducting nocturnal caregiving responsibilities. For example, an instance of a father’s passive uninvolvement in nocturnal caregiving is demonstrated by his report, “The other times I didn’t have to do anything because my wife was taking care of things.” Alternatively, an instance of a father’s active involvement in conducting nocturnal caregiving is demonstrated in his report, “I fed once, my wife fed twice. Both times I woke fully and helped her to burp the baby whenever she fed.” A more balanced approach for parents to conduct nocturnal infant caregiving could be for parents to establish predetermined strategies and assign tasks that optimize each other’s sleep, while also optimizing infant care.

In addition to a cultivating a balanced approach to nocturnal infant caregiving, and implementing predetermined nocturnal caregiving strategies, additional cooperative strategies can be made to optimize each other’s sleep and provide optimal nocturnal infant care. For instance, parents could make a concerted effort to maintain an adequate sleeping environment for the partner who is not actively providing care; thus, decreasing their partner’s transient nocturnal arousals. A mothers’ experience of an inadequate sleeping environment is demonstrated by her report, “…the third or fourth one [awakening] was because my husband was leaving for work and his alarm, and him getting ready, woke me up…”. A mothers’ experience of an adequate sleeping environment is demonstrated by a father’s report, “…and when I finally got-up, I took the baby downstairs so my wife could get some sleep…” Similar examples are provided for fathers’ experiences. A father’s experience of an inadequate sleeping environment is demonstrated by his report, “I woke up one time last night, [Mother] woke me up a little bit after I went to bed because the baby wouldn’t sleep.” A fathers’ experience of an adequate sleeping environment is demonstrated by a mother’s report that indicated her attempt to keep her husband from unnecessarily getting out of bed, “…and then I woke up later to get my husband ibuprofen, and then later to feed the baby again.” In addition to maintaining an adequate sleeping environment for one partner in the dyad, preservation of an adequate sleeping environment for the entire family system would likely pose benefit. The easiest and most straightforward way for both parents to decrease each other’s nocturnal sleep disruptions is to minimize superfluous disturbances. Examples of these disturbances include, “I woke up about seven times last night. The first time a friend texted me about 12:45…”; “I woke up… at 4:45 because dog woke me up…”; “I woke up twice last night the first time to care for the baby and the second time briefly when my cat jumped up on me.” As previously stated, each parent is part of a family system. By optimizing one parent’s sleep, the family system may in turn function more efficiently and safely during daytime activities.

DISCUSSION

This is among the first qualitative studies to compare and provide a description of nocturnal caregiving activities among first-time mothers and fathers during the early postpartum period. Mothers reported more nocturnal awakenings and more cumulative nocturnal wake time after sleep onset, per night, compared to fathers. Mothers’ nocturnal awakenings were primarily for infant feeding, general infant care, and infant changing; whereas, fathers’ awakenings were primarily passive-awakenings, for self-care, and for infant feeding. Overall, during nocturnal awakenings mothers performed a greater proportion of ‘infant care’ than fathers, and fathers performed a greater proportion of ‘self care’ and ‘partner care’ than mothers.

Mothers delivered the majority of nocturnal infant caregiving, even outside of feeding. However, Mothers’ role in feeding may play a large part in their accessibility to deliver, or engagement in, other nocturnal caregiving tasks that may contribute to the nocturnal caregiving imbalance. Furthermore, a balanced approach to nocturnal caregiving may not necessarily require a 50/50 split in responsibilities between mothers and fathers. Rather, a balanced approach could be considered adherence to predetermined caregiving strategies that are established by the postpartum couple. A disproportionate division of nocturnal caregiving might be ideal for some families, particularly those with one parent engaged in the outside workforce—as observed among the currents sample. A relief from some nocturnal caregiving tasks among working parents may be ideal to improve next day safety, especially given the clear acknowledgement that sleepiness has adverse effects on safety and performance in the workforce (see reviews, Walsh, Dement, & Dinges, 2005; McDonald, Patel, & Belenky, 2011).

The current study had considerable methodological strengths; however, limitations must be noted. The current study was conducted on a small homogenous sample of first-time postpartum dyads, which limited the ability to examine nocturnal caregiving as a function of diverse sample characteristics (e.g., parental work stati, parental marital stati, infant feeding method, and number of children in the household). Cultural differences could not be specifically evaluated in this study despite possible cultural differences in the provision of nocturnal infant care (e.g.,[Thoman, 2006]). Despite our description of nocturnal caregiving during the early postpartum experience, the postpartum period is characteristic of various changes and transitions that we were unable to examine (e.g., transitions from Family Medical Leave back to work, across infant development as nocturnal wake decreases). The current work calls for research to identify factors that promote differences in nocturnal caregiving behaviors (e.g., parenting efficacy), the effects of different nocturnal caregiving behaviors on infant developmental outcomes (e.g., attachment), and different nocturnal caregiving strategies that efficiently maximize parental sleep and minimize sleep disturbance related daytime impairments.

Clinical and Policy Implications

The current work provides insight into the nocturnal caregiving activities performed among first-time mothers and fathers during the early postpartum period. The postpartum reports revealed areas where new families can optimize each other’s sleep while providing optimal nocturnal infant care. Clinicians caring for newborns can provide anticipatory guidance for new parents and suggest coping strategies for them to implement. Specific strategies include a balanced approach to nocturnal infant caregiving, maintenance of an adequate sleeping environment for the partner who is not actively providing care, and to preserve an adequate sleeping environment for the entire family system. A balanced approach to nocturnal caregiving could be facilitated when couples predetermine and adhere to specific caregiving strategies. Clinical anticipatory guidance could also include information about the effects of sleep loss, as well as additional strategies to mitigate its negative consequences (e.g., utilizing personal support systems, and adjusting expectations around productivity and activities). Previous work indicates that many mothers with young infants do not frequently nap (Montgomery-Downs et al., 2010). Encouragement of daytime napping could be a compensatory strategy to help non-working new parents meet some of their sleep needs. The study results and observations can be used to extend current maternal postpartum sleep interventions (e.g., Stremler et al., 2006; Hiscock, Bayer, Hampton, Ukoumunne, & Wake, 2008; Lee & Gay, 2011) to include fathers, infants (e.g., Mindell, Kuhn, Lewin, Meltzer, & Sadeh, 2006), and the entire family system (e.g., Meltzer & Montgomery-Downs, 2011). The results may also be informative to the emerging literatures on childcare among single parents (e.g., Copeland & Harbaugh, 2010; Garfield & Chung, 2006), and paternal childcare involvement (e.g., Garfield, Clark-Kauffman, & Davis, 2006; Garfield & Isacco, 2006; Garfield & Isacco, 2012).

The nocturnal sleep experience among postpartum families is turbulent. Due to the influence that sleep has on daytime behaviors, new parents demonstrate impaired functioning in multiple domains (Insana & Montgomery-Downs, 2012). The effects of sleep disturbances on new parents may not alleviate until their nocturnal caregiving demands stabilize or the parents find ways to more efficiently manage their nocturnal caregiving responsibilities. In addition to the immediate family context, each family is nested within the larger societal culture that establishes parameters for families to function within (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Relevant to postpartum parents in the United States, the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) permits new parents 12 weeks of unpaid family leave for medical conditions, which include care for a newborn, if they are employed by a company with more than 50 employees (United States Department of Labor, 1993). However, the ability of a new family to go 12 weeks without income is impractical (e.g., Schuster et al., 2009) as is evidenced in our sample where almost 75% of the fathers were working full time during the study. As the multiple roles of new parents intersect (e.g., nocturnal caregiving and work responsibilities), new parents transmit back into society the sleep disturbed condition of their decision making, driving abilities, and work performance. Both researchers, and sleep disturbed individuals, acknowledge that sleepiness adversely affects safety and performance in the workforce (McGovern et al., 2011; Mellor & St, 2012 [also see reviews, Walsh et al., 2005; McDonald et al., 2011]); a father’s early morning thought was captured in the midst of his hazy awakening, “I’ve been pretty tired lately so it’s not really a good thing for me to be asleep at work, so I try to stay awake.” Thus, the current 1993 FMLA should be reevaluated in the context of today’s societal and financial demands imposed on developing families.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant R21HD053836 (HMD); T32GM081741 Behavioral and Biomedical Sciences Training Scholarship (SI); American Psychological Association of Graduate Students, Basic Psychological Science Research Grant (SI); and West Virginia University, Doctoral Student Research Support & Alumni Fund (SI). We thank the research participants and their families. Roslyn King’s, PhD, NIH conference on breastfeeding facilitated the collaboration among the authors. Data collection and processing were carried out with assistance from Megan Kraynok, Ph.D.; Chelsea Costello, B.A.; Laura Mancini, B.S.; and Eleanor Santy, B.A. Dr. Insana was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute T32 HL-082610-04 (Buysse); Dr. Garfield was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1K23HD060664-01A2 (CFG).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez GG, Ayas NT. The impact of daily sleep duration on health: a review of the literature. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2004;19(2):56–59. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2004.02422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball HJ, Hooker E, Kelly PJ. Parent-infant co-sleeping: Fathers’ roles and perspectives. Infant and Child Development. 2000;9(2):67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM. Mothers and Daughters “Do,” Fathers “Don’t Do” Family: Gender and Generational Bonds. Journal of Marriage & Family. 2006;86(4):812. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet MH. Performance and sleepiness as a function of frequency and placement of sleep disruption. Psychophysiology. 1986;23(3):263–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Boston: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Christie J, Poulton BC, Bunting BP. An integrated mid-range theory of postpartum family development: a guide for research and practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;61(1):38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman WL, Garfield C. Fathers and pediatricians: enhancing men’s roles in the care and development of their children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1406–1411. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland DB, Harbaugh BL. Psychosocial differences related to parenting infants among single and married mothers. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2010;33(3):129–148. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2010.498330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copinschi G. Metabolic and endocrine effects of sleep deprivation. Essent Psychopharmacol. 2005;6(6):341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield CF, Chung PJ. A qualitative study of early differences in fathers’ expectations of their child care responsibilities. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(4):215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield CF, Clark-Kauffman E, Davis MM. Fatherhood as a component of men’s health. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2365–2368. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield CF, Isacco A. Fathers and the well-child visit. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e637–e645. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield CF, Isacco A. Urban fathers’ involvement in their child’s health and healthcare. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2012;13(1):32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gay CL, Lee KA, Lee SY. Sleep patterns and fatigue in new mothers and fathers. Biol Res Nurs. 2004;5(4):311–318. doi: 10.1177/1099800403262142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG. The Discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Goel N, Rao H, Durmer JS, Dinges DF. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Seminars in Neurology. 2009;29(4):320–339. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlin-Jones BL, Burnham MM, Gaylor EE, Anders TF. Night waking, sleep-wake organization, and self-soothing in the first year of life. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22(4):226–233. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200108000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Y, Horne JA. The impact of sleep deprivation on decision making: a review. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2000;6(3):236–249. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.6.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock H, Bayer JK, Hampton A, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Long-term mother and child mental health effects of a population-based infant sleep intervention: cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e621–e627. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insana SP, Montgomery-Downs HE. Sleep and sleepiness among first-time postpartum parents: A field- and laboratory-based multimethod approach. Developmental Psychobiology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/dev.21040. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy HP, Gardiner A, Gay C, Lee KA. Negotiating sleep: a qualitative study of new mothers. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 2007;21(2):114–122. doi: 10.1097/01.JPN.0000270628.51122.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA, Gay CL. Can modifications to the bedroom environment improve the sleep of new parents? Two randomized controlled trials. Research in Nursing and Health. 2011;34(1):7–19. doi: 10.1002/nur.20413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J, Patel D, Belenky G. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 5. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. Sleep and performance monitoring in the workplace: The basis for fatigue risk management; pp. 775–783. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern P, Dagher RK, Rice HR, Gjerdingen D, Dowd B, Ukestad LK, et al. A longitudinal analysis of total workload and women’s health after childbirth. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2011;53(5):497–505. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318217197b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer AM, van den Wittenboer GL. Contribution of infants’ sleep and crying to marital relationship of first-time parent couples in the 1st year after childbirth. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(1):49–57. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor G, St JW. Fatigue and work safety behavior in men during early fatherhood. Am J Mens Health. 2012;6(1):80–88. doi: 10.1177/1557988311423723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, Montgomery-Downs HE. Sleep in the family. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2011;58(3):765–774. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1263–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery-Downs HE, Insana SP, Clegg-Kraynok MM, Mancini LM. Normative longitudinal maternal sleep: the first 4 postpartum months. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;203(5):465–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara K, Horiuchi S, Eto H, Uchida S. The development of infants’ circadian rest-activity rhythm and mothers’ rhythm. Physiol Behav. 2002;77(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00846-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation method. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LA. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AE, Caruso CC, Aldrich MS. Reliability of sleep diaries for assessment of sleep/wake patterns. Nursing Research. 1993;42(6):368–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. A room of their own: the social landscape of infant sleep. Nursing Inquiry. 2003;10(3):184–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2003.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Tikotzky L, Scher A. Parenting and infant sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(2):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster MA, Chung PJ, Elliott MN, Garfield CF, Vestal KD, Klein DJ. Perceived effects of leave from work and the role of paid leave among parents of children with special health care needs. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(4):698–705. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1101–1118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremler R, Hodnett E, Lee K, MacMillan S, Mill C, Ongcangco L, et al. A behavioral-educational intervention to promote maternal and infant sleep: a pilot randomized, controlled trial. Sleep. 2006;29(12):1609–1615. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoman EB. Co-sleeping, an ancient practice: issues of the past and present, and possibilities for the future. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10(6):407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikotzky L, Sadeh A, Glickman-Gavrieli T. Infant sleep and paternal involvement in infant caregiving during the first 6 months of life. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(1):36–46. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Labor, F. M. L. A. Family and Medical Leave Act. United States Department of Labor; 1993. Retrieved from http://www.dol.gov/whd/fmla/ [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JK, Dement WC, Dinges DF. Sleep medicine, public policy, and public health. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 648–656. [Google Scholar]