Abstract

Recent studies suggest that aliphatic β-nitro alcohols (BNAs) may represent a useful class of compounds for use as in vivo therapeutic corneoscleral cross-linking agents with higher order nitroalcohols (HONAs) showing enhanced efficacy over the mono-nitroalcohols. The current study was undertaken in order to evaluate the chemical stability of these compounds during storage conditions. Two mono-nitroalcohols (2-nitroethanol=2ne and 2-nitro-1-propanol=2nprop) and two HONAs, a nitrodiol (2-methyl-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol=MNPD), and a nitrotriol (2-hydroxymethyl-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol=HNPD) were monitored for chemical stability by 1H-NMR for up to 7 months. Each compound was studied at two concentrations (1% and 10%) either in unbuffered H2O or 0.2 M NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 (pH=5), and at 0°C and room temperature (RT) for a total of 8 conditions for each compound. The 1H-NMR spectra for the starting material were compared to subsequent spectra. Under all 4 of the conditions studied, both the nitrodiol (MNPD) and nitrotriol (HNPD) were stable for the duration of 7 months. 2nprop became unstable under all conditions at 3 months. 2ne was the most unstable of all the compounds tested. HONAs exhibit excellent chemical stability under long-term storage conditions. In contrast, the nitromonols tested are significantly less stable. These findings are relevant to the translation of this technology into clinical use.

Introduction

Riboflavin-mediated photochemical stabilization of the cornea (also known as CXL=corneal cross-linking) is an exciting new treatment paradigm in Ophthalmology and is revolutionizing the field of corneal therapeutics. In the short period since its inception in the late 1990's (1), CXL has been proven both effective and safe in stabilizing patients with keratoconus (KC) and post-LASIK keratectasias and is becoming standard of care throughout the world. The cross-linking procedure effectively halts the progression of KC and can be accompanied by an improvement in both corneal curvature (i.e. flattening or “normalization” of astigmatism) and/or visual acuity. Briefly, the procedure involves the removal of the outer corneal epithelial layer followed by the application of a 0.1% riboflavin-containing solution to the exposed underlying corneal stromal bed. After confirming adequate infiltration of the riboflavin photosensitizer, a 360 nm emitting light source is used to irradiate the central corneal region for up to 30 minutes at 3 mW/cm2(2).

Despite these successes, the CXL therapy poses attendant risks and drawbacks related to the use of UVA irradiation, the need for epithelial removal (for riboflavin penetration into the corneal stroma), cytotoxicity, and light source accessibility (for the sclera); and has yet to be approved for clinical use in the US. The long-term effects of UV light exposure to the eye are unclear. UVA irradiation has been implicated in a number of deleterious effects, including lens cortical cataract and retina degeneration (3). Epithelial removal is a painful procedure and increases one's risk for incurring a corneal infection, which has been reported following CXL (4). Additionally, because the photochemical cross-linking procedure is cytotoxic to cells, extreme caution is used in treating particularly thin corneas (<400um) where the risk of corneal endothelial cell damage is increased, a complication that can lead to detrimental corneal swelling and associated opacification (5). Finally, several research groups, including ours, are exploring the possibility of using chemical cross-linking for scleral stabilization as a means to limit pathologic axial growth in progressive myopia. In this case, a chemical cross-linking approach may be favored over the photochemical method, since administration to the sclera via a sub-Tenon's injection can be performed safely and repeatedly. Previous efforts to apply the riboflavin photochemical approach to scleral cross-linking have been reported. However, several issues not applicable to corneal cross-linking arise when considering the sclera (particularly the posterior sclera) and include toxicity to the neural retina and accessibility of the UVA light source to the posterior scleral region (6). In favor of this photochemical approach, a single sub-Tenon's injection can diffuse readily throughout the sub-Tenon's space, contacting a wide area of the sclera. Thus, in lieu of such concerns and potential benefits, the development of an alternative cross-linking approach that could avoid the use of UVA light, avoid epithelial removal (for the cornea), is less cytotoxic, and could provide cross-linking to the posterior sclera without requiring a light source, is of significant interest to the field of Ophthalmology. This has prompted a search for candidate chemical cross-linking agents that could be used for therapeutic stabilization of either the cornea and/or sclera.

There are hundreds of cross-linking agents that have been used for a variety of purposes including both industrial as well as biomedical applications. The areas of application are vast and there is significant overlap. For example, formaldehyde (7) and glutaraldehyde (8), two of the most widely used cross-linking agents, are used in the production of resins for manufacturing plywood, textiles, etc, as well as for leather-making and rubber-hardening for tires. They have also been used in important biomedical applications such as fixation of bioprostheses (i.e. heart valves, skin grafting materials, etc), biological scaffolds, hydrogels, and tissue fixation for histology/pathology. Some of the many commercially used cross-linking agents include other aldehyde agents such as glyceraldehyde (9), methyl glyoxal (10); the group of carbodiimides (11), genipin (12), imidoesters such as dimethyl adipimidate and dimethyl suberimidate, Denacol-epoxys, derivatives of ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, derivatives of methylenebisacrylamide, divinyl benzene, The lists are seemingly endless.

Although many of these compounds are excellent cross-linking agents for in vitro cross-linking applications, the list of available agents is much more limited when considering their possible use as in vivo tissue cross-linking agents. Several aspects that are less relevant when considering in vitro use, become critical when considering their use in a living being. Such considerations for the cornea include: efficacy under physiologic pH and temperature, permeability, coloration and effects on light transmission, and toxicity. The latter includes cytotoxicity, organismal toxicity, and genotoxicity (i.e. mutagenicity/carcinogenicity).

Our recent studies suggest that the class of aliphatic β-nitroalcohols may fulfill many, if not all, of the criteria needed to permit further testing in human clinical trials. Nitroalcohols can function as a formaldehyde delivery system under conditions of physiologic pH and temperature (13). In addition, their small size and water solubility favor permeability (14), have little effects on light transmission (15), and furthermore, although they function to deliver formaldehyde, are considerably less toxic than formaldehyde (16) and test negative in genotoxicity testing (National Toxicology Program 2012).

A straight-forward study was carried out over 7 months in order to check the chemical stability of 4 compounds of potential therapeutic interest. They are two mononitroalcohols, 2-nitroethanol (2ne) and 2-nitro-1-propanol (2nprop), a nitrodiol 2-methyl-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol (MNPD), and a nitrotriol 2-hydroxy-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol (HNPD). The conditions of storage used were similar to those found in ophthalmic drop formulations. The results show that the HONAs are stable under the present storage conditions whereas the mono-nitroalcohols are not stable. The experimental setup is described in the following section.

Materials and Methods

2-nitroethanol (2ne), 2-nitroethane, 2-nitro-1-propanol (2nprop), NaH2PO4, Na2HPO4, deuterium oxide (D2O), acetone (D6) were all obtained from the Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO). 2-methyl-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol (MNPD, MW=135) and 2-hydroxymethyl-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol (HNPD, MW=151) were obtained from TCI America (Portland, OR). Millipore water (<18.2M•.cm) was used in all the experiments.

Methods explanation: stability tests by 1 H NMR (400 MHz)

Two mono-nitroalcohols (2-nitroethanol=2ne and 2-nitro-1-propanol=2nprop) and two HONAs, a nitrodiol (2-methyl-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol=MNPD), and a nitrotriol (2-hydroxymethyl-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol=HNPD) were monitored for chemical stability by 1H-NMR for up to 7 months on either a Bruker 400MHz or 500MHz NMR instrument. Each compound was studied at two concentrations (1% and 10%) either in unbuffered H2O or 0.2 M NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 (pH=5), and either at room temperature (RT) or 0°C for a total of 8 conditions for each compound (see Table 1). Unbuffered solutions of H2O were noted to maintain pH in the range of 7.0-7.14 throughout the duration of the testing. The 1H-NMR spectra for the starting material were compared to subsequent spectra as monitored at various time points (10d, 1mo, 3mo, 7mo). All 1H-NMR spectra were recorded in solution. The formation of new peaks over time indicates decomposition of the starting material and hence chemical instability. Similarly, the absence of new peaks indicates chemical stability. No effort was made to identify decomposition products as this was not the intent of the study.

Table 1. Summary of results of stability testing of nitroalcohols.

| [C] | Temp. |

|

|

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 d | 3 mo | 7 mo | 10 d | 3 mo | 7 mo | 10 d | 1 mo | 10 d | 1 mo | 3 mo | ||

| 1% in H20 | RT | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| 0°C | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | |

| 10% inH2o | RT | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| 0°C | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | |

| 1% in pH5 | RT | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| 0°C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | |

| 10% in pH5 | RT | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − |

| 0°C | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | |

denotes stable

denotes unstable

For the unbuffered samples, an aliquot of the storage solution was added to a round bottom flask and H2O was removed under vacuum via rotary evaporator. The residual was then dissolved in either deuterated water (D2O) or deuterated acetone ((CD3)2CO = acetone-d6). For pH5 buffered samples, an aliquot of the storage solution was first extracted with diethyl ether in order to exclude the buffer. After removing the diethyl ether under vacuum, the residual was dissolved in D2O or acetone-d6, in an identical fashion to the unbuffered samples.

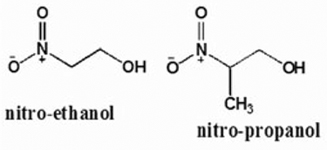

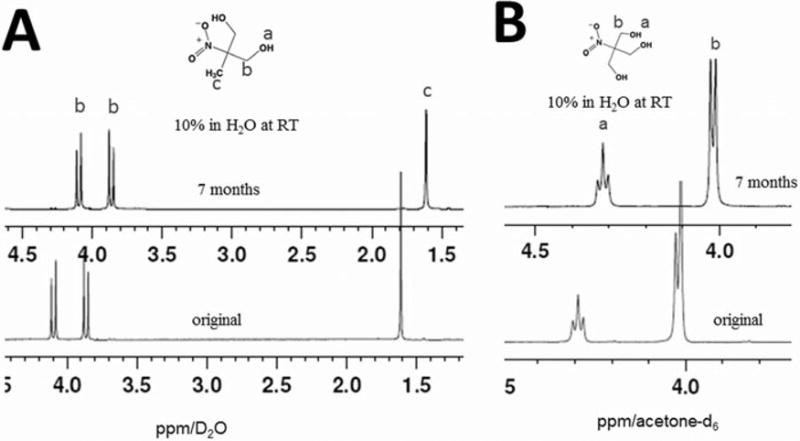

As an experimental note, deuterated (deuterium=2H, symbolized as D) solvents are preferred for use in 1H-NMR in order to avoid proton interference coming from the solvent in which the spectra are taken. For example, acetone and H2O produce peaks at 2.05ppm and 2.8ppm respectively. If these solvents were used for the nitro-diol measurements (see Figure 1A), peak from these solvents would be present in between the peaks for the nitro-diol protons, which are located at 1.6ppm and ca. 4.0ppm, complicating the overall spectrum. If, as in this case, D2O is used as a solvent, the spectrum is much clearer, as shown. Contaminating water from the original sample can also distort the spectrum, and so it is important to fully dry the samples prior to reconstituting in deuterated solvents. Chemical shifts were measured relative to trimethylsilane (TMS) as previously described in a standard fashion (17). It should be pointed out that the chemical shift for a given compound may differ depending on the solvent condition used.

Figure 1.

Results of higher order nitroalcohol stability studies [all spectra at 400MHz]. (A) 1H-NMR spectra are shown for the nitrodiol MNPD in D2O. The three proton peaks (bottom) of original as expected, don't change after 7 months in H2O at RT (top). Two doublets (b) are from non-equivalent methylene groups. Also, because the NMR medium was D2O, hydrogen bonding and proton exchange eliminates the hydroxyl proton peak (a) in this spectrum. MNPD is stable after 7 months in H2O at RT. (B) 1H-NMR spectra are shown for nitrotriol HNPD in acetone-d6. The two proton peaks (a) and (b) [bottom spectrum] of original don't change after 7 months in H2O at RT (top spectrum). Thus, HNPD is stable after 7 months in H2O at RT.

Results and Discussion

As nitroalcohol therapeutic corneoscleral cross-linking moves toward use clinically, it becomes increasingly more important to determine compound stability under storage conditions. The optimal method for topical application (to either the cornea or sclera) will be ultimately determined by the degree of effect weighed against any toxicity. For the cornea, the use of these compounds as an eye drop for ongoing daily patient use remains a possibility. However, there are advantages to delivering cross-linking solutions via alternative delivery methods such as a corneal reservoir, hydrogel contact lens, etc. Regardless of the delivery method employed it will be important to have available chemical stability data since in most cases periodic dosing of some form will likely be required in a patient-based setting. Thus, the results of this study have implications for the development of these agents as topical ophthalmic pharmaceuticals.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) provides an outstanding analytical technique for determining the course of reactions. The starting materials, reactive intermediates and final products can be detected in real time often with minimal interference and with quantification of the species involved. In particular, proton (1H) NMR is a particularly powerful method since the signals and chemical shifts of the protons in organic molecules appear in distinct regions of the spectrum and the signals are quantitative related to each other by integration. We show below that 1H NMR can be used as a singlet spectroscopic method to quantitatively determine the stability of nitroalcohols under various conditions of temperature, concentration and pH.

Typical expected 1H-NMR spectra were identified for each of the compounds tested and were in agreement with existing literature. These are shown as figures 1 and 2. As shown in figure 1, the spectrum for the nitrodiol MNPD shows three sets of proton peaks: the methyl protons shown as a singlet at ca. 1.6ppm, and two doublets at ca. 3.85 and 4.1ppm. The two doublets [(b) in figure 1A.] are from non-equivalent methylene group s and two protons are coupled each other forming two doublets. As is the case with the 2nprop signal (figure 2B) because the NMR medium was D2O, hydrogen bonding and fast proton-deuterium exchange eliminates the hydroxyl proton peak for MNPD [(a) in Fig 1A]. The spectrum for the nitrotriol HNPD shows two sets of proton peaks for the starting material, one for the hydroxyl protons (n=3) at ca. 4.02ppm and one for protons of the alpha carbons (n=6) at ca. 4.3ppm. The hydroxyl proton coupled with the two alpha carbon protons gives a triplet and correspondingly, a doublet is observed for the alpha carbon protons.

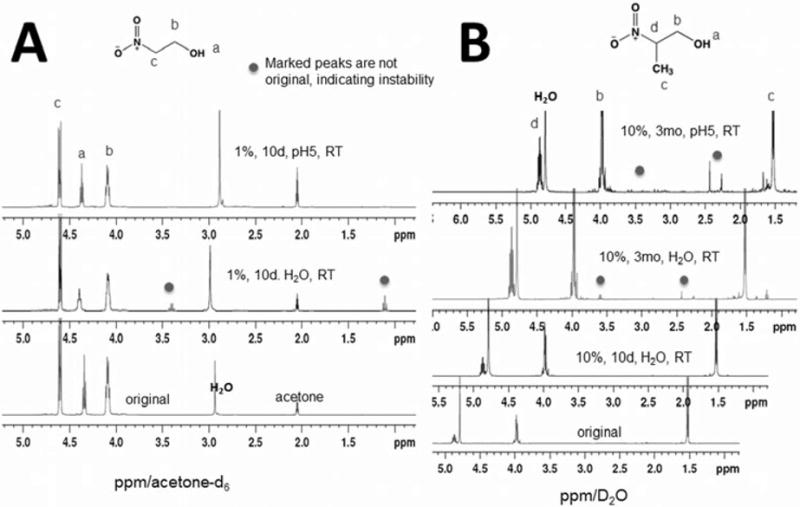

Figure 2.

Results of mononitroalcohol stability studies [all spectra at 400MHz]. (A) 1H-NMR spectra are shown for 2ne in acetone-d6. The three proton peaks (bottom) of the original are as expected. In the middle curve of 2ne in H2O for 10 days, the peak at 4.35ppm (a) moved to a less shielded higher frequency field (4.4ppm). There are two new sets of peaks, a triplet at 1.1ppm and a quartet at 3.4ppm with integration 3 and 2, respectively, suggesting that there are –CH3 and -CH2 groups in the decomposition product that couple each other. In pH5 buffer for 10 days, however, the 1H-NMR spectrum (top) is the same as the original. Thus, 2ne is unstable in H2O but is stable in pH5 buffer at RT for 10 days. (B) 1H-NMR spectra are shown for 2nprop in D2O. The bottom curve belongs to the original sample. The spectrum of 2nprop in H2O at RT for 10 days (lower middle) is the same as the original (bottom). However, after 3 months in H2O and pH5 buffer at RT, the spectra (upper two) changed. There are new peaks observed between 1.5 to 3.9ppm. Also, because the NMR medium was D2O, hydrogen bonding and proton exchange eliminates the hydroxyl proton peak (a) in this spectrum. Thus, 2nprop is stable in H2O at RT for 10 days but is unstable after 3 months at RT both in H2O and pH5 buffer.

As shown in figure 2A, three sets of proton peaks for the original 2ne are seen, as expected, at ca. 4.1, 4.38, and 4.6ppm. Labeled (b) protons at 4.1 ppm are a quartet due to coupling with adjacent methylene protons (c) and the hydroxyl proton (a). The spectrum of 2nprop (figure 2B) either in H2O or at RT at 10 days was as the original. Peaks are seen at ca. 3.95, 4.8, and 4.89ppm, as well as the 2-methyl group protons seen ca. 1.5ppm. Also, because the NMR medium was D2O, hydrogen bonding and proton exchange eliminates the hydroxyl proton peak.

Mononitroalcohols become unstable with time

The monols showed instability under these storage conditions. 2ne was the most unstable of all the compounds tested, becoming unstable in unbuffered solution at 10 days. As shown in Figure 2A in the middle curve for 2ne in H2O for 10 days, the peak at 4.35ppm labeled as (a) has moved to a less shielded higher frequency field (4.4ppm). In addition, there are two new sets of peaks, a triplet at 1.1ppm and a quartet at 3.4ppm with integration 3 and 2, respectively, suggesting that there are -CH3 and -CH2 groups in the decomposition product that couple each other. Sample stability in this case was improved by storage under pH5 acidic conditions but storing in the cold at 0°C did not improve stability. The 2nprop signal was stable at the 10 day period but became unstable at 3 months. Several new peaks ca. 2.2-2.5ppm and 3.0-4.0ppm were noted at 3 months under all 8 conditions. To reiterate, at 3 months, the 2nprop instability was not affected by reagent concentration, solvent, or temperature.

In our previous experience, we have noted a dark reddish-brown color change to occur during storage of commercially obtained 2ne and 2nprop neat solutions. This color change was evident by simple visual inspection. One of the solutions had turned from virtually clear with a slight yellow tint to a dark orange-yellow, indicating the formation of light absorbing impurities. At that time and in response to our inquiry, the chemical supplier carried out a quality assurance QA analysis of our particular reagents. Using gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (GC/FID), the QA analysis identified a 2ne signal peak change from 97.4% to 86.3% purity. No information on chemical stability from the supplier was known at the time (personal communication with Sigma-Aldrich technical support January 2006).

Previous studies using 2-bromo-2-nitro-1,3-propanediol, or Bronopol (BP), suggest likely decomposition mechanisms for nitroalcohols such as those included in this report. The initial decomposition of BP in aqueous alkali is a pH and temperature dependent retro-nitroaldol reaction to give formaldehyde and 2-bromonitroethanol. Reaction of formaldehyde with the starting material produces the nitrotriol HNPD as a major product (18, 19, 20, 21). Using 1H-NMR, we confirmed a similar mechanism for 2-nitro-1-propanol which forms the nitrodiol MNPD (16). Secondly, the liberation of nitrite to 35% occurs during BP decomposition and is second-order. This can be accelerated by heating at 100oC in aqueous alkali (22). Consistent with that study, we also found that nitrite is produced during aqueous alkali decomposition of 2ne, 2nprop, MNPD, and HNPD up to a similar extent. Of note, heating in alkali to produce nitrite can be used to measure nitroalcohols in solution by coupling the denitration with a simple colorimetric nitrite assay (23). Finally, it should be mentioned that 2,2-dinitroethanol can also form from BP decomposition and causes a deep reddish-brown color change (24). As pointed out earlier in this results section, both 2ne and 2nprop can form such coloration upon long-term storage raising the possibility that 2,2-dinitroethanol or 2,2-dinitropropanol respectively, may form.

Importantly, such compound instability may also explain unusual differences in prior results of Ames testing performed on 2ne (25). Ames testing is routinely performed to determine chemical mutagenicity using various strains of Salmonella typhimurium. The earliest reported result on 2ne Ames testing was in 1984. In that analysis, 2ne was found to be equivocal using several common TA strains of Salmonella. However, a repeat analysis in 1988 showed mutagenicity in three strains, including TA98. This particular strain was negative in 1984 but was positive in 1988. Other inconsistencies in the mutagenicity profile were also noted at that time. Communication with the principal investigator (PI) of the study, Dr. Errol Zieger confirmed that the original 2ne bottle was used for both studies and was stored at RT in the interim. In other words, the 2ne sample was kept for approximately 4 years between testing dates! In lieu of the contradictory results of the Ames trial and considering our finding of 2ne instability in solution over just 10 days, it would be reasonable to postulate that the 1988 results could be related to degradation products. Most recently, the National Toxicology Program (NTP) under Dr. Christine Witt, performed an extensive battery of high throughput genotoxicity screens on 2ne. These studies included testing for caspase 8, 9, and 3/7 activation, general cytotoxicity (conducted in 13 different cell types from 5 species), activation of p53 and various additional stress response pathways including heat shock 70 protein and the antioxidant response element, hERG channel interference, disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, and interaction with a long list of nuclear receptors. These studies also included Ames testing on the TA98 strain which were reported as negative in 1984 and positive in 1988. The current round of NTP Ames testing using the TA98 strain showed no activity when using a freshly prepared/obtained sample of 2ne. This finding supports the possibility that the 1988 testing was performed on a chemically degraded sample. Furthermore, they have concluded that 2ne is inactive in all of their testing, confirming absence of any genotoxic effects (personal communication, July 2011).

Higher order nitroalcohols remain stable with time

In contrast to the instability of the mononitroalcohols, the HONAs, MNPD and HNPD, were found to be remarkably stable. At 7 months of storage under various conditions, under all the conditions tested, these two compounds remained stable. In even the most unfriendly conditions for decomposition in our study, unbuffered H2O at a high 10% concentration kept at room temperature, the compounds were stable. Table 1 summarizes the results of the stability studies of the 4 BNAs. It should be pointed out that these conditions are relatively mild by comparison with systematic industry monitored stability testing similar to those undertaken prior to market release.

The World Health Organization has outlined standards for formal systematic pharmaceutical stability testing and shelf-life/re-test period determination (26). Such testing includes temperature storage in 10°C increments, strict humidity control, a simulating container/closure system, pH testing, etc. Testing is conducted on different primary batches of production material. These tests are reserved for compounds well on their way to clinical application. On the other hand an initial study such as ours regarding chemical stability during several different storage conditions provides valuable information at this early stage of drug development. Our results showed that under the selected conditions the HONAs (MNPD and HNPD) remained stable for 7months while the nitromonols (2ne and 2nprop were unstable during that time period. We conclude by noting that the HONAs are both more effective and have longer shelf life than the monols. These findings are relevant to translation of this technology into clinical use.

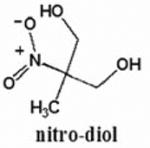

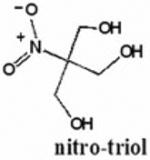

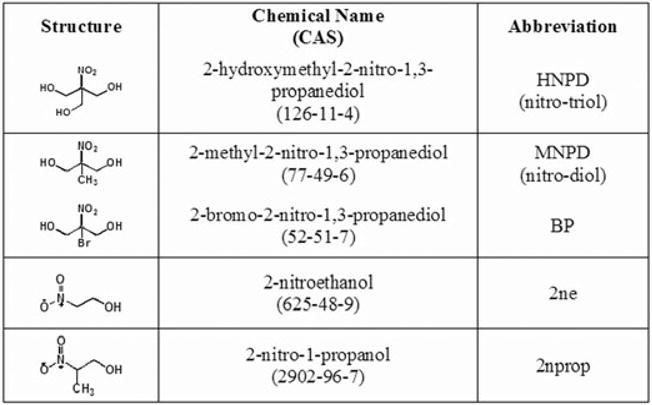

Chart 1. The chemical structures of the β–nitroalcohols studied in this work.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by Research to Prevent Blindness, NCRR/NIH UL1RR024156, NIH/NEI P30 EY019007, NIH/NEI R21EY018937 (dcp) and R01EY020495 (dcp), and NSF grant CHE 11 11398 (njt).

Footnotes

This paper is part of the Special Issue honoring the memory of Nicholas J. Turro

References

- 1.Spoerl E, Huhle M, Seiler T. Induction of cross-links in corneal tissue. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66:97–103. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wollensak G. Crosslinking treatment of progressive keratoconus: new hope. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:356–360. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000233954.86723.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spoerl E, Mrochen M, Sliney D, Trokel S, Seiler T. Safety of UVA-riboflavin cross-linking of the cornea. Cornea. 2007;26(4):385–389. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3180334f78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez-Santonja JJ, Artola A, Javaloy J, Alio JL, Abad JL. Microbial keratitis after corneal collagen crosslinking. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1138–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollensak G, Sporl E, Reber F, Pillunat L. Corneal endothelial cytotoxicity of riboflavin/UVA treatment in vitro. Ophthalmic Res. 2003;35:324–328. doi: 10.1159/000074071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wollensak G, Iomdina E, Dittert DD, Salamatina O, Stoltenburg G. Cross- linking of scleral collagen in the rabbit using riboflavin and UVA. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83:477–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heck HD, Casanova M, Starr TB. Formaldehyde toxicity – new understanding. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1990;20(6):397–426. doi: 10.3109/10408449009029329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimni ME. Glutaraldehyde fixation revisited. Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants. 2001;11(3&4):151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollensak G. Thermomechanical stability of sclera after glyceraldehydes crosslinking. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:399–406. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart JM, Schultz DS, Lee OT, Trinidad ML. Exogenous collagen cross-linking reduces scleral permeability: modeling the effects of age-related cross-link accumulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(1):352–357. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lui Y, Gan L, Carlsson DJ, Fagerholm P, Lagali N, Watsky MA, Munger R, Hodge WG, Priest D, Griffith M. A simple, cross-linked collagen tissue substitute for corneal implantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(5):1869–1875. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai CC, Huang RN, Sung HW, Liang HC. In vitro evaluation of the genotoxicity of a naturally occurring crosslinking agent (genipin) for biologic tissue fixation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52:58–65. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200010)52:1<58::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon MR, O'Connor NA, Paik DC, Turro NJ. Nitroalcohol induced hydrogel formation in amine-functionalized polymers. J Appl Polym Sci. 2010;117:1193–1196. doi: 10.1002/app.31944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen Q, Kim MJ, Trokel SL, Paik DC. Aliphatic β-nitroalcohols for therapeutic corneoscleral cross-linking: corneal permeability considerations. Cornea. 2013;32(2):179–184. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31825646de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik DC, Wen Q, Braunstein RE, Airiani S, Trokel SL. Initial studies using aliphatic beta-nitro alcohols for therapeutic corneal cross-linking. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2008;50:1098–1105. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paik DC, Solomon MR, Wen Q, Turro NJ, Trokel SL. Aliphatic beta- nitroalcohols for therapeutic corneoscleral cross-linking: chemical mechanisms and higher order nitroalcohols. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2010;51:836–843. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottlieb HE, Kotlyar V, Nudelman A. NMR chemical shifts of common laboratory solvents as trace impurities. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7512–7515. doi: 10.1021/jo971176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryce DM, Croshaw B, Hall JE, Holland VR. The activity and safety of the antimicrobial agent Bronopol (2-bromo-2-nitropropan-1,3-diol) J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1978;29:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kireche M, Peiffer JL, Antonios D, Fabre I, Gimenez-Arnau E, Pallardy M, Lepoittevin JP, Ourlin JC. Evidence for chemical and cellular reactivities of the formaldehyde releaser bronopol, independent of formaldehyde release. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:2115–2128. doi: 10.1021/tx2002542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kajimura K, Tagami T, Yamamoto T, Iwagami S. The release of formaldehyde upon decomposition of 2-bromo-2-nitropropan-1,3-diol (Bronopol) J Health Sci. 2008;54(4):488–492. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Provan GJ, Helliwell K. Determination of bronopol and its degradation products by HPLC. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2002;29:387–392. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(02)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanyal AK, Basu M, Banerjee AB. Rapid ultraviolet spectrophotometric determination of bronopol: application to raw material analysis and kinetic studies of bronopol degradation. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1996;14:1447–1453. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(96)01779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen Q, Paik DC. A simple method for measuring aliphatic beta-nitroalcohols using the Griess nitrite colorimetric assay. Exp Eye Res. 2012;98:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Challis BC, Yousaf TI. The reaction of germinal bromonitroalkanes with nucleophiles. Part 1. The decomposition of 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol (‘Bronopol') in aqueous base. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1991;2:283–286. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeiger E, Anderson B, Haworth S, Lawlor T, Mortelmans K. Salmonella mutagenicity tests: V. Results from the testing of 311 chemicals. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 1992;19(S21):2–141. doi: 10.1002/em.2850190603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations. Forty-third report. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. Stability testing of active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished pharmaceutical products; p. 87. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 953. Annex 2. [Google Scholar]