Abstract

Objective

The study aimed to determine the prevalence of dysmenorrhea in female adolescents living in Tbilisi, Georgia; find possible risk factors and establish an association, if any, with nutrition and sleep hygiene.

Material and Methods

A cross-sectional study was used. A retrospective case control study was used to identify risk factors. Participants: A total of 2561 women consented to participate in the research. 431 participants were included in the case-control study. Interventions: Detailed questionnaire included: reproductive history, demographic features, menstrual pattern, severity of dysmenorrhea and associated symptoms; information about nutrition and sleep hygiene.

Results

The prevalence of dysmenorrhea was 52.07%. Due to pain, 69.78% reported frequent school absenteeism. The risk of dysmenorrhea in students who had a family history of dysmenorrhea was approximately 6 times higher than in students with no prior history. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea was significantly higher among smokers compared with non-smokers 3.99% vs. 0.68% (p=.0.05 OR:6.102). Those women reporting an increased intake of sugar reported a marked increase of dysmenorrhea compared to women reporting no daily sugar intake (55.61% vs. 44.39%, p=.0023 LR:0.0002). However, alcohol, family atmosphere and nationality showed no correlation with dysmenorrhea. Our study revealed two most important risk factors of dysmenorrhea: meal skipping 59.78% vs. 27.03%, p=.00000 LR: 0.00000 OR:4.014 and sleep hygiene-receiving less sleep 38.77% vs. 19.59%, p=0.000055 LR: 0.000036 OR:2.598.

Conclusion

Primary dysmenorrhea is a common problem in the adolescent population of Tbilisi Geogia. It adversely affects their educational performance. Meal skipping and sleep quantity are associated with dysmenorrhea and may cause other reproductive dysfunctions.

Keywords: Primary dysmenorrhea, adolescent, nutrition, sleep, lifestyle

Özet

Amaç

Çalışma Tiflis, Gürcistan’da yaşayan adolesan kızlarda dismenore prevalansını belirlemeyi, olası risk faktörlerini bulmayı ve eğer varsa beslenme ve uyku hijyeni ile ilişki kurmayı amaçlamıştır.

Gereç ve Yöntemler

Kesitsel çalışma yapıldı. Risk faktörlerini tanımlamak için retrospektif olgu kontrol çalışması kullanıldı. Katılımcılar: toplam 2561 kadın araştırmaya katılmak için olur verdi. Olgu-kontrol çalışmasına 431 katılımcı dahil oldu. Girişim: Ayrıntılı anket şunları içermekteydi: reprodüktif öykü, demografik özellikler, menstrual patern, dismenorenin şiddeti ve ilişkili semptomlar; beslenme ve uyku hijyeni hakkında bilgiler.

Bulgular

Dismenore prevalansı %52.07 idi. %69.78’i ağrı nedeniyle sık olarak okula gidemediğini bildirdi. Ailede dismenore öyküsü olan öğrencilerde dismenore riski, öyküsü olmayan öğrencilerden yaklaşık 6 kez daha yüksekti. Dismenore prevalansı sigara içenlerde sigara içmeyenlerle kıyaslandığında anlamlı olarak daha yüksekti, %3.99’a karşılık %0.68 (p=.0.05 OR: 6.102). Artmış şeker alımı bildiren kadınlar, günlük şeker alımı olmadığını bildiren kadınlara kıyasla belirgin dismenore artışı rapor etti (%55.61’e karşılık %44.39, p=0.0023, LR:0.0002). Buna karşın, alkol, aile çevresi ve uyruk dismenore ile bir korelasyon göstermedi. Çalışmamız dismenorenin en önemli iki risk faktörünü ortaya çıkardı: öğün atlama %59.78’e karşılık %27.03, p=0.00000, LR:0.00000, OR:4.014 ve uyku hijyeni-az uyumak %38.77’ye karşılık %19.59, p=0.000055, LR: 0.000036, OR:2.598.

Sonuç

Primer dismenore Tiflis Gürcistan‘ın adolesan populasyonunda yaygın bir problemdir. Eğitim performanslarını olumsuz olarak etkilemektedir. Öğün atlama ve uyku miktarı dismenore ile ilişkilidir ve diğer reprodüktif işlev bozukluğuna neden olabilir.

Introduction

Except for the newborn and early infant years, no period of the human life span encompasses more dramatic changes than does adolescence. Providing optimal health care to individuals of this age group requires an in depth understanding of the biological, cognitive, and sociocultural changes that occur, their interrelatedness and their potential impact on an adolescent’s health (1). Primary dysmenorrhea is by far the most common gynecological problem in this age group (2). Studies conducted on female adolescents report the prevalence range of primary dysmenorrhea from 20% to 90% (3). Morbidity due to dysmenorrhea represents a substantial public health burden. It is one of the leading causes of absenteeism from school and work and is responsible for significant loss of earnings and diminished quality of life (4–8). Despite its high prevalence and associated negative effects, many women do not seek medical care for this condition (9).

In primary dysmenorrhea, no pelvic pathological feature is identified; an inflammatory response, mediated by prostaglandins and leukotrienes causes lower abdominal cramps and systemic symptoms. The following risk factors have been associated with more severe episodes of dysmenorrhea: earlier age at menarche; long menstrual periods; heavy menstrual flow; smoking and positive family history, obesity and alcohol consumption (10–13). Physical activity and the duration of the menstrual cycle do not appear to be associated with increased menstrual pain (11). There is a lack of data of an association between primary dysmenorrhea and nutritional deficiency despite the fact that adolescence is a peak time for eating disorders (14). Adolescents require increased nutrients to sustain the rapid growth of the brain, bones, body tissues, and sexual maturation. Significant nutritional deficiencies in adolescence can lead to decreased adult height, osteoporosis, and delayed sexual maturity (15). To meet the energy requirements of adolescents, a variety of food sources is recommended, with 60% of calories from carbohydrates, 10% to 20% from protein, and less than 30% from fat (15). The role of diet in the pathogenesis of dysmenorrhea is discussed in the literature and results are diverse. There are no clear recommendations on dietary habits, but there are clear points. The effects of dieting may bring women to the attention of the gynecologist and may be responsible for symptoms that may not seem readily related to dieting.

Dietary behaviors and associated chronic disease risk factors established during adolescence have been shown to track into adulthood, suggesting that adolescence is a key time to address nutritional issues such as meal skipping (16–18). In Georgia there is lack of information about the nutritional status of adolescents and its relationship to reproductive health. There is existing evidence that adequate nutrition plays a key role in achieving normal adult size and reproductive capacity, which increases our interest in this issue.

To our knowledge, a review of studies focusing on sleep and primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents is at present absent. There are several converging reasons to focus on sleep regulation in relation to primary dysmenorrhea and adolescent development:

Sleep appears to be particularly important during periods of brain maturation.

There are substantial biological and psychosocial changes in sleep and circadian regulation which exist across pubertal development.

Increasing evidence exists that many adolescents frequently obtain insufficient sleep.

There is mounting evidence that sleep deprivation has its greatest negative effects on the control of behavior, emotion, and attention, which is a regulatory interface critical in the development of social and academic competence, and psychiatric disorders (19).

The outcomes of inadequate or dysfunctional sleep are well documented. Sleep affects immune, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular function and can have an effect on menstrual disorder.

A six-year longitudinal study among adolescents given a ten- hour sleep opportunity suggested that adolescents needed nine hours of sleep on average (20, 21). Healthy young adults, who were deprived of sleep for forty hours, showed increased circulating pro- and anti-inflammatory factors (22). The association of sleep deprivation, pain, and inflammatory processes is seen in a variety of medical disorders and conditions (23).

Material and Methods

The study was conducted with two-stage cluster sampling. The primary unit of random selection was the capital of Georgia, Tbilisi. Selection of clusters used probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling, based on statistic data collected in 2008. With cluster sampling, the schools and universities to be included were first selected. Enrollment data in these schools was obtained from the Ministry of Education. The second stage consisted of systematic equal probability sampling. Students were randomly selected from within the selected schools and they were eligible to participate in the survey. Informed consent was obtained from respondents before collecting data. A specially designed form providing information about the study was given to respondents. Since this study involved disclosure of intimate knowledge, participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. Parents’ consent letters were also given to the students explaining what the study was all about and reassuring them that the information obtained would be strictly anonymous and confidential.

A letter was previously sent to heads of all selected schools for their consent to undertake the survey. The purpose and details of the survey were discussed with the school authorities.

The teachers and school personnel were not present during administration of the questionnaire to encourage the students to provide their own answers without influence. Out of 2890 selected, 2561 agreed to participate. They answered survey questions in the classroom, and all of them underwent a physical exam. Vital Signs: Blood pressure, heart rate, respiration rate and temperature were checked. Anthropometry: Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and pelvic ultrasound was conducted in all students. Based on including and excluding criteria, 431 students were included in the case control study. The medical school “Aieti” ethics committee approved the study protocol. Students were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

The eligibility criteria included the following:

Age 14–20 with clinical signs of dysmenorrhea

Nulliparity

Written or oral informed consent.

Exclusion criteria included:

Acute or chronic pelvic pathology that can be a cause of secondary dysmenorrhea.

Physical illness affecting eating behavior or causing pain

Any history of mental illness or a structural abnormality that could account for pain or sleep

Planning pregnancy

Taking any kind of psychotropic drugs

Refusal to participate

Information about the girls’ reproductive history was gathered. Ultrasound was conducted again in all participants to rule out pelvic pathology. The questionnaire included data regarding demographic features, menstrual pattern (menarche age, cycle length, menstrual flow length, and menstrual blood quantity) use of contraception, severity of dysmenorrhea and associated symptoms, the body area, frequency, intensity (if pain was experienced during the last three cycles), number of years of painful menstruation, duration of pain, region of pain, presence of other complaints accompanying dysmenorrhea and impact of menstrual pain on daily activities. In addition, the questionnaire addressed information about menstrual abnormalities in close relatives, extra genital pathologies and treatments used. The questions were also related to the impact of dysmenorrhea on school performance and attendance.

A retrospective case control study was used to identify risk factors. In the focus group were included adolescents suffering from dysmenorrhea with no underlying pelvic pathology. In the control group: healthy adolescents, with regular menstrual cycles, no physiological or somatic complaints during menstruation.

Questions concerning nutrition were straightforward. Students were asked to circle the number of meal intakes throughout the 24 hours. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends at least six servings of grains and at least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day. So, twice or less meal intake was considered as infrequent food intake.

Gibney and Wolever (24), classifies an eating episode as an event that provides at least 50 kcal, and, as generally one snack does not provide the above mentioned amount, we did not regard it as “meal” intake. We considered that meal skipping can be used as a screening tool to identify adolescents of unhealthy nutrition, since meal skipping is associated with numerous health-compromising eating behaviors and less adequate dietary intakes. Excessive carbohydrate and sugar intake was determined based on individual self-report of excessive consumption of bread, table sugar, soda, chocolate, ice cream and sweets in their daily diet (25). Nine possible responses ranging from “never” to “six or more times a day” were recorded. Four and more was considered as excessive. Some other questions included: Which meals do you regularly eat? When do you snack? What are your favorite snack foods? Do you think you have healthy eating habits? We consider that this questionnaire is reliable, for rapid assessment of eating habits. However, we are aware that it is hardly ever possible to assess the absolute validity of dietary questions in population-based surveys (26).

There is evidence supporting the validity of self report sleep habits surveys, when the goal is to describe group-level sleep patterns of large samples of adolescents (27, 28).

Questions were: What time do you go to bed on school days? What time do you wake up? On school days when do you go to bed? How long does it take you to fall asleep? How many times a week are you awake the whole night? Based on answers, we calculated hours of sleep received in the participant 2890 women aged 14–20 years who were randomly selected. A total of 2561 women consented to participate in the research. 431 participants were in the case-control study. Participants were divided in two groups. One group comprised 148 healthy women with no dysmenorrhea and with regular ovulatory cycles, the second group consisted of 276 women suffering from painful menstruation, and 7 participants were excluded due to genital malformation.

The survey data were analyzed using the SPSS version 13.0.

Results

The prevalence of dysmenorrhea was 52.07%. In the adolescent population of Tbilisi. Georgia Case group- #1 adolescents with dysmenorrhea the mean age of the girls was 16.03±1.39 years, age of menarche 12.58±.2, menstrual flow duration 4.92±1.36.days. Control group-#2, healthy adolescents without dysmenorrhea: the mean age was 15.55±0.87 years, age of menarche 12.74±1.06 years, menstrual flow duration.4.53±1.24 days. BMI of participant was 23±1.

Out of women from group having dysmenorrhea kg/m2, 63.7% started experiencing pain from 12–15 years, 36.3% reported late development of the disease from 15 to 19 years, 16.88% of adolescent associated onset of painful cycles with psychological stress, 13.42% -with physical work, and 11.26% reported a stressful event before the start of painful cycles. Other factors reported were: allergic reactions in 7.79%, frequent viral or bacterial infection in 9.92%, and start of sexual activity in 1.3%

Analysis showed that the occurrence of dysmenorrhea differed significantly among students in high school, compared with university, with a higher prevalence in school compared with universities, which can be due to age (87.68% vs 12.32% p<0.001, LR 0.0007).

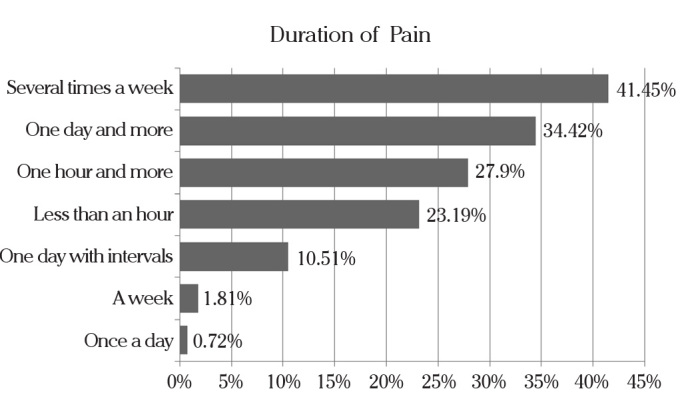

Most patients, 34.42%, reported a duration of pain of one day and more: 27.90% one hour and more. 23.19% less than an hour, 10.51%, one day with intervals, −1.81%. a week: The majority of women, 43.84%, reported localization of pain in the lower part of the abdomen and 5.94% in the lumbar region, or both 27.17% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pain duration reported

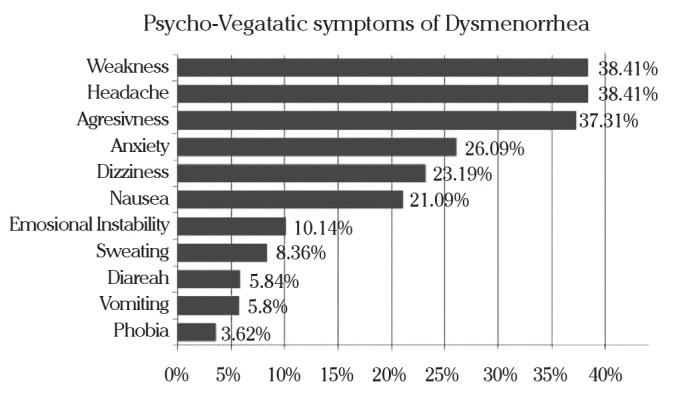

Pain associated with menstruation is also accompanied by various other symptoms. Associated physiological symptoms are presented in Figure 2. Due to pain and the presented symptoms, 69.78% reported frequent school absenteeism.

Figure 2.

Psycho-vegetatic symptoms associated with dysmenorrhea

The risk of dysmenorrhea in students who had a family history of dysmenorrhea was approximately 6 times higher than in students with no prior history. Questions included mother and anyone in the family separately. Although in Georgia there is high degree of attachment and close family relationship, the most positive answers were checked with the mother. Other gynecological diseases in the mother did not influence the prevalence of dysmenorrhea (Table 1).

Table 1.

Gynecological family history and dysmenorrhea

| Dysmenorrhea | P (Asymp. Sig.) | Odds | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysmenorrhea | Healthy | Pearson Chi-Square | Likelihood ratio | Ratio | ||

| Menstrual cycle irregularity | yes | 23.19% | 15.54% | 0.063055 | 0.058665 | 1.641 |

| no | 76.81% | 84.46% | ||||

| Dysmenorrhea | yes | 30.43% | 6.76% | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 6.038 |

| no | 69.57% | 93.24% | ||||

| Amenorrhea | yes | 5.43% | 2.03% | 0.097123 | 0.078711 | 2.778 |

| no | 94.57% | 97.97% | ||||

| Premenstrual syndrome | yes | 5.80% | 2.03% | 0.073679 | 0.057007 | 2.974 |

| no | 94.20% | 97.97% | ||||

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | yes | 6.52% | 2.70% | 0.091020 | 0.075388 | 2.512 |

| no | 93.48% | 97.30% | ||||

The prevalence of dysmenorrhea was significantly higher among smokers compared with non-smokers 3.99% vs. 0.68% p.0.05 OR 6.102. d, Our results revealed a significant difference between high and low intakes of sugar products and frequency of dysmenorrhea. Those women reporting an increased intake of sugar reported a marked increase of dysmenorrhea compared to women reporting no daily sugar intake, 55.61% vs. 44.39% p<0.001 LR 0.0002. However, alcohol, family atmosphere and nationality showed no correlation with dysmenorrhea. Our study revealed the two most important risk factors of dysmenorrhea to be meal skipping- inadequate nutrition 59.78% vs 27.03% p<0.001 LR 0.00000 OR 4.014 and sleep hygiene-receiving less sleep 38.77% vs. 19.59% p .0.001 LR 0.000036 OR 2.598. All studied risk factors are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk factors of dysmenorrhea

| Dysmenorrhea | P (Asymp. Sig.) | Odds | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Yes | No | Pearson Chi-Square | Likelihood ratio | Ratio | ||

|

| ||||||

| Education | High school | 87.68% | 97.97% | 0.000344 | 0.000071 | 6.790 |

|

|

||||||

| college | 12.32% | 2.03% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Living conditions | Satisfactory | 93.12% | 95.95% | 0.238306 | 0.224929 | 0.572 |

|

|

||||||

| non satisfactory | 6.88% | 4.05% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Family income | High income | 9.42% | 19.59% | 0.012283 | 0.014966 | |

|

|

||||||

| medium income | 85.51% | 75.68% | ||||

|

|

||||||

| poverty | 4.35%) | 2.70% | ||||

|

|

||||||

| refugee | 0.72% | 2.03% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Family atmosphere | Harmonic | 83.27% | 89.19% | 0.100820 | 0.093935 | 0.603 |

|

|

||||||

| conflictive | 16.73% | 10.81% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol use | Yes | 4.35% | 3.38% | 0.627653 | 0.623123 | 1.300 |

|

| ||||||

| No | 95.65% | 96.62% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Tobacco use | Yes | 3.99% | 0.68% | 0.050112 | 0.028883 | 6.102 |

|

| ||||||

| No | 96.01% | 99.32% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Drug use | Yes | 1.45% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| No | 98.55% | 100% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Sleep hygeine | Yes | 38.77% | 19.59% | 0.000055 | 0.000036 | 2.598 |

|

| ||||||

| No | 61.23% | 80.41% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Meal skipping | Yes | 59.78% | 27.03% | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 4.014 |

|

| ||||||

| No | 0.22% | 72.97% | ||||

|

| ||||||

| School absenteeism | Yes | 56.88% | 45.95% | 0.031456 | 0.031468 | 1.552 |

|

| ||||||

| No | 43.12% | 54.05% | ||||

We also studied the association of dysmenorrhea with extra-genital pathology. No association was observed between reported diabetes, thyroid diseases, gastro-intestinal, vascular, or renal diseases. Allergy reaction in patients with dysmenorrhea was more frequent, 14.23% compared with the healthy group 4.73% Pearson Chi-Square 0.003 Likelihood Ratio 0.001494 Odds Ratio 3.343.

On the question of what relieved pain, half of the women, 50.72%, used medication for the management of their pain, 17. 69% used rest, napping as pain relief, 13.08% used trying to concentrate on other tasks, 14. 23% preferred a horizontal position, 4.23%did not specify. Medications used for dysmenorrhea were: NSAID’s 9.82%, other pain relievers, analgesics 71.78%, spasmolytics 6.13%, combined oral contraceptives 9.82%.

Discussion

It is estimated that the prevalence of dysmenorrhea varies from 20% to 95% (29–31). The results of this study confirm that dysmenorrhea is common in young women, as 52.0% of our sample experienced dysmenorrhea. We consider that variation of the prevalence may be due to different diagnostic tools or different attitudes of different cultures towards menstruation. Geographic location cannot be ignored as in Turkey, on the border of Georgia, the prevalence of dysmenorrhea was quite close 55.5% (32). According to another study, prevalence in northern Turkey was also 53.6% (33). We want to mention that this is the first and only study in our country examining the prevalence of dysmenorrhea, but in Turkey in other studies the prevalence of painful menstruation was low. Polat reported 45.3% (34) Cakir reported 31.2% (35).

The highest number of women having dysmenorrhea, 57%, was observed at the age of 14. As the mean age of menarche in our sample was 12.58±1.2, dysmenorrhea occurred soon after the onset of menstruation. We found no significant difference in the mean age of menarche between the two groups. Our data differs from many other studies where age of menarche is an important factor (36–39). The same results were observed by Pawlowski, who did not find any difference in the ages of menarche between dysmenorrheic and non-dysmenorrheic women (40).

Again, our research pointed out that primary dysmenorrhea causes recurrent absenteeism from school, or other activities. Despite great advances in the study of the pathogenesis and treatment options, the fact that students tended to be absent from school, unable to focus on their courses, and distracted from lectures due to dysmenorrheal symptoms, is stable. As Ondervan in 1998 indicated that dysmenorrhea is responsible for school absenteeism, later other studies from 2000- through 2007 again confirm female adolescents absenteeism was common due to excessive pain (36, 41–44).

Although a high percentage of women suffer with pain each month, which leads to school absenteeism, our study highlighted that most women do not seek medical advice. It is known that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are highly effective, but most participants are unaware of the effectiveness of the treatment. Only 9.82% used NSAID’s. In our country university entrance exams are conducted on a pre-determined day, so it is important to be aware of treatment options, if menstruation coincides with examinations. There is need to educate girls and their parents regarding effective dysmenorrhea treatment, emphasizing NSAID use, appropriate dosing, including prophylactic administration and dosing frequency.

Our results demonstrated that the prevalence of dysmenorrhea was dependent on family income. Similarly, Widholm and Kantero noted a higher prevalence of dysmenorrhea among higher income groups (45). However, some researchers have indicated that economic status is not consistently associated with dysmenorrhea, suggesting that further research is necessary to clarify this factor (46).

Our research indicated that, while no particular gynecologic disease in the mother is a predictor of dysmennorhea, family history of dysmenorrhea seems to be an important risk factor for women with dysmenorrhea. The results are consistent with previous studies (32, 44, 47).

Our study identifies tobacco to be an important risk factor. Previous studies have found an association between current cigarette smoking and the prevalence of dysmenorrhea (48, 49). We agree that cigarette smoking may increase the duration of dysmenorrhea, presumably because of nicotine-induced vasoconstriction (50).

Our study demonstrated that meal skipping significantly increases the prevalence of dysmenorrhea. To our knowledge, this is the first research that considered meal skipping as a risk factor, although there are several studies suggesting that nutrition during adolescence affects reproductive function in young women and dysmenorrheal as well. A low-fat vegetarian diet was associated with a decrease in duration and intensity of dysmenorrhea in young adult women (7). Dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids had a beneficial effect on the symptoms of dysmenorrhea in adolescents in one study (29).

Nonetheless, it has been demonstrated that menstrual regularity can be influenced by diet (51). Specific dietary nutrients may have direct effects or exert their effects by altering the status of circulating sex steroids. So, as inadequate nutrition is a cause of low energy availability and can alter hormonal status, we consider that meal skipping causes menstrual disorders.

Our study revealed that sugar consumption was associated with the prevalence of dysmenorrhea. We found only one study that observed same results. A possible explanation that Nebahat Ozerdogan provided was that sugar interferes with the absorption and metabolism of some vitamins and minerals, thus causing nutritional imbalances, which in turn can cause difficulty in muscle functioning and lead to muscle spasms (32). We consider excessive sugar can alter circulating steroid quantity, but further research is necessary to prove this hypothesis.

Excessive sleepiness among children and adolescents has become a major international health concern. There are several reports of poor sleep hygiene and sleep disorders in pediatric groups (52).

Our study also indicated that a high percent of the Georgian adolescent population report late sleeping habits and getting inadequate sleep. The data is consistent with large-scale community surveys, and between 14 and 33% of adolescents report a subjective need for more sleep (53–57).

Our study once again demonstrated that, despite cultural differences, adolescents’ worldwide sleep is significantly less than the recommended 9–10 h. Although our study has limitations, findings strongly point out that self-reported shortened total sleep time, is negatively associated with primary dysmenorrhea. We consider that the effect of sleep disorder on dysmenorrhea is due to the fact that the sleep/wake rhythm seems to be influenced by the estrogen and progesterone receptors and vice versa. It well known that sleep deprivation compromises cognitive, emotional, neurologic, metabolic, and immune functions and thereby can have a great effect on reproductive health (58).

We also found that frequent overnight wakefulness can affect dysmenorrhea. The same results were shown by a survey of 2264 participants, that women working a shift schedule, found an increase in dysmenorrhea and menstrual irregularity (27).

Sleep deprivation has an impact on dysmenorrhea and reproductive health, but a more detailed assessment is necessary to specify this effect. Our study is a step forward to emphasize that, despite its significance and frequency, sleep disturbance is an area of adolescent health that is almost entirely unaddressed.

Conclusion

Primary dysmenorrhea is a common problem in the adolescent population of Tbilisi, Geogia. It adversely affects their educational performance. As most students are unaware of effective treatment, we suggest improving female adolescents’ self-care behavior towards dysmenorrhea through enhanced health education in schools. The findings of this study can serve as a guide to healthcare providers who want to design an effective systematic menstrual health education program for female adolescents. Meal skipping is associated with dysmenorrhea and may cause other reproductive dysfunctions. Meal skipping and excessive sugar consumption can be used as a screening tool to identify adolescents in need of nutrition education. Future management of dysmenorrheal pain may be considered a promising nutritional therapy for the relief of pain and symptoms associated with dysmenorrhea. However, large, prospective, and controlled studies will be necessary to establish the findings of this study. At this point professionals should educate teens on the adverse effects associated with meal skipping, including, excessive snacking of unhealthy foods. The results of this study suggest that sleep quality and sleep hygiene has a great effect on reproductive health quality. Disturbed sleep can be both a cause and a result of ill health and,if recognized, can improve adolescent development and reproductive health. Sleep deprivation is associated with a variety of adverse consequences, which are often not appreciated by patients or clinicians. In summary, dysmenorrhea trials are especially important because this condition is undertreated and leads to high morbidity in adolescence.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Alain J. Why adolescent medicine? Medical Clinics of North America. 2000;84:769–85. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrow C, Naumburg E. Dysmenorrhea Primary Care. Clinics in Office Practice. 2009;36:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, Gülmezoglu M, Khan KS. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunstein JB, Hausfeld J, Hausfeld J, London A. Economics of reducing menstruation with trimonthly-cycle oral contraceptive therapy: Comparison with standard-cycle regimens. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:699–708. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cote I, Jacobs P, Cumming D. Work loss associated with increased menstrual loss in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:683–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kjerulff KH, Erikson BA, Langenberg PW. Chronic gynecological conditions reported by US women: Findings from the National Health Interview Survey, 1984–1992. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:195–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnard K, Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM. Health status among women with menstrual symptoms. J Womens Health. 2003;12:911–9. doi: 10.1089/154099903770948140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones GL, Kennedy SH, Jenkinson C. Health-related quality of life measurement in women with common benign gynecologic conditions: A systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:501–11. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.124940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillard PJ. Consultation with the specialist: Dysmenorrhea. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:64–71. doi: 10.1542/pir.27-2-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harlow SD. A longitudinal study of risk factors for the occurrence, duration and severity of menstrual cramps in a cohort of college women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:1134–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersch B. An epidemiologic study of young women with dysmenorrheal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:655–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundell G. Factors influencing the prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea in young women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:588–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbold NH, Frates SE. Update on nutrition guidelines for the teen: trends and concerns. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:303–9. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenneth J, Grimm Michelle M, Diebold . Textbook of Family Medicine, The Periodic Health Examination. 7th ed. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haines Jess, Stang Jamie. Promoting Meal Consumption among Teens journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:945–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotani K, Nishida M, Yamashita S, Funahashi T, Fujioka S, Tokunaga K, et al. Two decades of annual medical examinations in Japanese obese children. Do obese children grow into obese adults? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;2:912–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J, et al. Longitudinal changes in diet from childhood into adulthood with respect to risk of cardiovascular diseases. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1038–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahl RE. Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:175–84. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carskadon MA, Acebo C. Regulation of sleepiness in adolescents: update, insights, and speculation. Sleep. 2002;25:606–14. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.6.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carskadon M, Orav E, Dement W. Evolution of sleep and daytime sleepiness in adolescents. Raven Press; New York: 1983. pp. 201–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey DJ, Fleshner M, Wright KP., Jr The effects of 40 hours of total sleep deprivation on inflammatory markers in health young adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:1050–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haack M, Sanchez E, Mullington JM. Elevated inflammatory markers in response to prolonged sleep restriction are associated with increased pain experience in healthy volunteers. Sleep. 2007;30:1145–52. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibney M, Wolever T. Periodicity of eating and human health: present perspective and future directions. Br J Nutr. 1997;77:3–5. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Block G. A review of validations of dietary assessment methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:492–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tibbitts GM. Sleep disorders: causes, effects, and solutions. Prim Care. 2008;35:817–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Seifer R, Fallone G, Labyak SE, et al. Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. SLEEP. 2003;2:213–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harel Z. A contemporary approach to dysmenorrhea in adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2002;4:797–805. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200204120-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu CS, Yang JK, Yang LL. Effect of a dysmenorrheal Chinese medicinal prescription on uterus contractility in vitro. Phytother Res. 2003;17:778–83. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tonini G. Dysmenorrhea, endometriosis and premenstrual syndrome. Minerva Pediatr. 2002;54:525–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nebahat O, Deniz S. Prevalence and predictors of dysmenorrhea among students at a university in Turkey. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;107:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulsen E, Funda O. Dysmenorrhea Prevalence among Adolescents in Eastern Turkey: Its Effects on School Performance and Relationships with Family and Friends. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001;23:267–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polat A, Celik H. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in young adult female university students. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;279:527–32. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0750-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ir M, Mungan I, Karakas T, Girisken I, Okten A. Menstrual pattern and common menstrual disorders among university students in Turkey. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:938–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel V, Tanksale V, Sahasrabhojanee M, Gupte S, Nevrekar P. The burden and determinants of dysmenorrhoea: a population-based survey of 2262 women in Goa, India. BJOG. 2006;113:453–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexiou VG, Ierodiakonou V, Peppas G, Falagas ME. Prevalence and impact of primary dysmenorrhea among Mexican high school students. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107:240–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zukri SM, Naing L, Hamzah TNT, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea among medical and dental university students in Kelantan: prevalence and associated factors. IMJ. 2009;16:93–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loto OM, Adewumi TA, Adewuya AO. Prevalence and correlates of dysmenorrhea among Nigerian college women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:442–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pawlowski B. Prevalence of menstrual pain in relation to the reproductive life history of women from the Mayan rural community. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31:1–8. doi: 10.1080/03014460310001602072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. The prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in women in the U.K: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:93–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banikarim C, Chacko MR, Kelder SH. Prevalence and impact of dysmenorrhea on Hispanic female adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:1226–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.12.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Stöven H, Schwarzenberger J, Schmucker P. Pain among children and adolescents: restrictions in daily living and triggering factors. Pediatrics. 2005;115:152–62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CH, Lin YH, Heitkemper MM, Wu KM. The self-care strategies of girls with primary dysmenorrhea: a focus group study in Taiwan. Health Care Women. 2006;27:418–27. doi: 10.1080/07399330600629583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Widholm O, Kantero R. Correlations of menstrual traits between adolescent girls And their mothers. Acta Obstet Gynecal Scand. 1971;50:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein JR, Litt IF. Epidemiology of adolescent dysmenorrheal. Pediatrics. 1981;68:661–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rostami M. The study of dysmenorrhea in high school girls. Pak JMed Sci. 2007;23:928–31. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, et al. The prevalence of pelvic pain in the United Kingdom: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:93–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proctor M, Farquhar C. Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhea. BMJ. 2006;332:1134–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7550.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hornsby PP, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR. Cigarette smoking and disturbance of menstrual function. Epidemiology. 1998;9:193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill PB, Garbaczewski L, Haley N, et al. Diet and follicular development. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984;39:771–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.5.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gahan F, Judith A, Owens J. Sleepiness in children and adolescents: clinical implications. Sleep medicine reviews. 2002;6:287–306. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kirmil-Gray K, Eagleston JR, Gibson E. Sleep disturbance in adolescents: Sleep quality, sleep habits, beliefs about sleep, and daytime functioning. J Youth Adolesc. 1984;13:375–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02088636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manni R, Ratti MT, Marchioni E, Castelnovo G, Murelli R, Sartori I, et al. Poor sleep in adolescents: A study of 869 17-year-old Italian secondary school students. J Sleep Res. 1997;6:44–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1997.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morrison DN, McGee R, Stanton WR. Sleep problems in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:94–9. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patten CA, Choi WS, Gillin JC, Pierce JP. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking predict development and persistence of sleep problems in US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;106:23–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saarenpää-Heikkilä O, Laippala P, Koivikko M. Subjective daytime sleepiness and its predictors in Finnish adolescents in an interview study. Acta Pædiatr. 2001;90:552–7. doi: 10.1080/080352501750197700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mark G, Reijonen Goetting Jori. Pediatric Insomnia: A Behavioral Approach Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2007;34:177–444. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]