Abstract

Serous borderline ovarian tumors (SBOT) generally occur in young women, present at early stages and are associated with an excellent prognosis. However, there are rare subtypes of SBOT which may exhibit a more aggressive course. In contrast with other types of SBOT, the micropapillary variant SBOT (SBOT-MP) tends to present at advanced stages. Herein, we present a rare case of a SBOT-MP that occurred in a 66-year-old woman, who had tumoral involvement on bilateral ovaries, sigmoid serosa and a positive peritoneal cytology. The currently recommended treatment options for these cases are also discussed.

Keywords: Borderline ovarian tumor, peritoneal implant, micropapillary, advanced stage, postmenopause

Özet

Seröz borderline over tümörleri (SBOT) genellikle genç kadınlarda ortaya çıkmakta, erken evrede tanı almakta ve çok iyi bir prognoza sahip olmaktadır. Ancak, SBOT’nin daha agresif bir seyir gösterebilen nadir alt tipleri mevcuttur. Diğer SBOT’lerin aksine, SBOT’nin mikropapiller varyantı (SBOT-MP) ileri evrelerde ortaya çıkma eğilimindedir. Bu yazıda, 66 yaşındaki postmenopozal bir kadında ortaya çıkan, bilateral overlerde ve sigmoid kolon serozasında tutuluma ve pozitif peritoneal sitolojiye sahip nadir bir SBOT-MP olgusu sunulmaktadır. Ayrıca, bu tip olgular için güncel tedavi önerileri de tartışılmaktadır.

Introduction

Serous tumors account for 60% of all epithelial ovarian tumors, and are classified into three groups: benign, borderline and malignant. Serous borderline ovarian tumors (SBOT) constitute 9–15% of all serous neoplasms. With respect to invasive ovarian cancer, borderline tumors generally occur in younger women at childbearing age. Fortunately, these tumors are generally diagnosed at early stages, and have a favorable prognosis (1).

However, there are subtypes of SBOTs that are associated with a more aggressive behavior and an unfavorable outcome. Herein, we report a case of a bilaterally located micropapillary variant of SBOT resembling an invasive ovarian malignancy at an advanced stage with serosal sigmoid implants and positive peritoneal cytology in a postmenopausal woman. The currently recommended treatment approaches for these tumors are also discussed.

Case Report

A 66-year-old woman who had been postmenopausal for 22 years applied to our institution with pelvic pain and abdominal distention that initially occurred four months before admission. Her past medical and family histories were unremarkable. A pelvic mass predominantly located in the right lower quadrant was palpated on pelvic examination. On transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS), she was found to have bilateral cystic pelvic masses with peripheral solid areas, each measuring 10 cm in diameter. Pelvic computerized tomography (CT) revealed bilateral heterogeneous pelvic masses with irregular surface contours and solid components. Circulating serum tumor markers were within the normal reference range (CA125: 22.2, CA19-9: 0.56, CA15-3: 8.7, AFP: 2.2, CEA: 1.7).

Exploratory laparotomy was performed. Minimal peritoneal fluid accumulation was observed, which was sampled for cytological analysis. Solid-cystic masses on both ovaries were present, each measuring about 10 cm in size. There were multiple tumoral implants on the sigmoid colon serosa, the largest measuring 5 mm. Other peritoneal surfaces were macroscopically normal.

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed initially, and the masses were sent for frozen section analysis. Both of the masses were reported to be serous ovarian tumors with at least borderline histology. Total abdominal hysterectomy, omentectomy, bilateral pelvic and paraaortic lymph node dissection and appendectomy were performed for staging purposes. Tumoral implants were excised from the sigmoid colon serosa and the defects were primarily repaired. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged from the hospital on the third postoperative day.

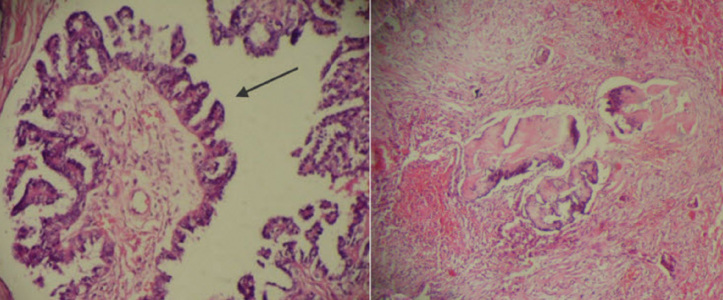

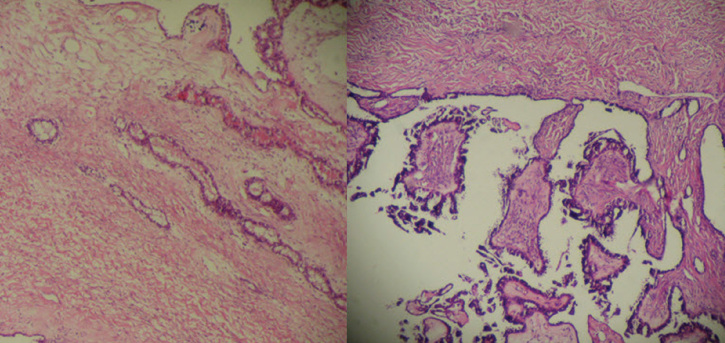

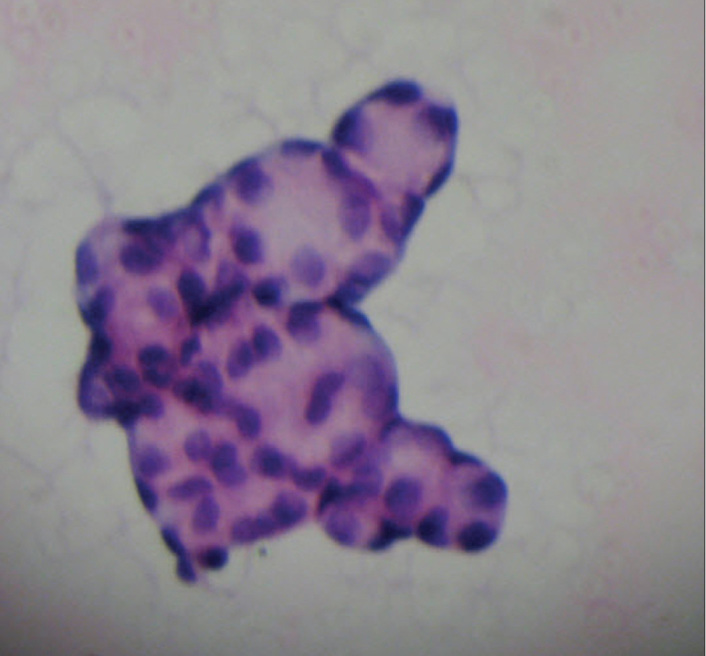

On final pathological examination, a micropapillary variant of SBOT on both ovaries and peritoneal implants on sigmoid serosa were reported (Figure 1). The implants on the sigmoid serosa were non-invasive (Figure 1). The tumor had both endophytic and exophytic invasion patterns (Figure 2). Cytological washings were also positive for tumor cells (Figure 3). Pelvic and paraaortic lymph nodes, omentum and appendix were free of any tumoral involvement. After consultation with the medical oncology department, adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin was planned.

Figure 1.

Micropapillary pattern of the tumor (left image) (H&E ×200) and Non-invasive peritoneal implant on sigmoid serosa (right image) (H&E×40)

Figure 2.

Endophytic (left) and exophytic (right) growth pattern of the tumor (H&E ×40)

Figure 3.

Cytologic examination demonstrating tumor cells forming a papillary pattern (H&E ×400)

Discussion

Borderline ovarian tumors (BOT) were initially described by Taylor et al. (2) in 1929. As these tumors are most commonly diagnosed at reproductive ages, fertility sparing is important for most of the patients. Subsequent pregnancies with normal obstetric outcomes may be achieved, especially in younger patients (3). In the case presented here, a serous type BOT with micropapillary pattern occurred in a 66-year-old postmenopausal woman, which is a rare presenting age for BOTs.

Serous BOTs constitute the most common type among BOTs. These are well-differentiated tumors and generally have an indolent growth pattern. However, they have a higher rate of recurrence than other types of BOT and progression to invasive carcinoma is not uncommon (4). SBOTs are bilateral in 30% of cases, and extra-ovarian spread may develop in about 30% of these (5). Interestingly, our case had multiple peritoneal implants on the sigmoid serosa, but other peritoneal surfaces were free of tumoral involvement. SBOTs are usually detected at early stages (6). The presenting stage is considered the most important factor for predicting recurrence. Our case presented as stage III-B disease. Positive peritoneal cytology rates increase with advancing tumor stage (7). In our case, cytology was also positive.

According to histopathological features, SBOTs are classified into two groups: typical non-invasive proliferative type SBOT and micropapillary SBOT (SBOT-MP) type, which is also termed micropapillary serous carcinoma (MPSC). SBOT-MPs are further classified into non-invasive and invasive types. Invasive SBOT-MP is the most common histologic type (8). It is characterized by small micropapillae that infiltrate the underlying ovarian stroma (Figure 1). As in primary invasive ovarian tumors, invasive SBOT-MPs may be associated with peritoneal implants. Some researchers consider the presence of invasive peritoneal implants as a poor prognostic sign (9). The case presented here had non-invasive implants on the sigmoid serosa, which may be associated with a better prognosis than cases with invasive implants.

Unlike the proliferative type SBOTs, SBOT-MPs have a higher risk of presenting at an advanced stage, having bilateral ovarian involvement, ovarian capsule invasion, positive peritoneal cytology, stromal microinvasion and extra-ovarian implants (particularly invasive) (10). Moreover, SBOT-MPs with an exophytic surface growth pattern have a higher association with extra-ovarian surface implants and recurrence (9). Thus, it is important to distinguish proliferative SBOT and SBOT-MP tumors at the time of initial diagnosis. In our case, micropapillary histology, bilateral ovarian involvement, positive peritoneal cytology and presence of serosal implants placed the patient at high risk for recurrence.

Treatment of BOTs mainly consists of surgical resection of the tumor and its macroscopic implants, and may be performed via either laparoscopy or laparotomy. During surgery, pelvic structures, all peritoneal surfaces including sub-diaphragmatic area and intestinal serosa should be thoroughly examined to rule out extra-ovarian disease. Fertility sparing surgery in terms of cystectomy or unilateral oophorectomy is an acceptable option in cases with future fertility desire and low risk for recurrence. There are also publications suggesting that lymph node dissection may be avoided in such cases (11). However, for cases of SBOT with completed childbearing, a complete surgical staging approach with pelvic and paraaortic lymph node dissection is recommended for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes, as nearly 30 percent of women with SBOTs have extraovarian disease spread. Moreover, 6 to 27 percent of those with a frozen section diagnosis of serous borderline tumor will be upgraded to invasive cancer on final pathological examination (12). As previously mentioned, our case had multiple high risk factors for recurrence; thus, complete staging surgery was undertaken. Especially for postmenopausal patients with SBOT-MP, we recommend an extensive surgical intervention, as for invasive serous ovarian carcinomas. These cases should also have long-term follow-up visits, as there may be recurrences even 10 years after initial treatment (13).

Although considered ineffective by some authors, chemotherapy is commonly used in advanced stages of disease, especially with extraovarian implants, as done in our case (14).Well-designed future studies are needed to clarify the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of SBOT at advanced stages.

In summary, we presented a case of bilateral SBOT-MP tumor with extraovarian spread in a postmenopausal patient. Complete staging procedures with optimal cytoreductive efforts are strongly recommended in these cases in order to achieve high cure rates and minimal disease related morbidity and mortality.

Footnotes

The case has been previously presented in part as an abstract in a local obstetrics and gynecology meeting (Zekai Tahir Burak Gunleri 2011, Antakya, Turkey).

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Shi X, Zhao C. Research Developments on the Histopathology and Prognostic Predictors of Serous Borderline Tumor of Ovary. Clin Oncol Cancer Res. 2009;6:169–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor HC. Malignant and semimalignant tumors of the ovary. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1929;48:204–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanat-Pektas M, Ozat M, Gungor T, Dikici T, Yilmaz B, Mollamahmutoglu L. Fertility outcome after conservative surgery for borderline ovarian tumors: a single center experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:1253–8. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1804-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo MM, Salamanca CM, Miller M, Symowicz J, Leung PC, Oliveira C, et al. Serous borderline ovarian tumors in long-term culture: phenotypic and genotypic distinction from invasive ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1234–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanetta G, Rota S, Chiari S, Bonazzi C, Bratina G, Mangioni C. Behavior of borderline tumors with particular interest to persistence, recurrence, and progression to invasive carcinoma: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2658–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogg R, Scurry J, Kim SN, Friedlander M, Hacker N. Microinvasion links ovarian serous borderline tumor and grade 1 invasive carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozkara SK. Significance of peritoneal washing cytopathology in ovarian carcinomas and tumors of low malignant potential: a quality control study with literature review. Acta Cytol. 2011;55:57–68. doi: 10.1159/000320858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yemelyanova A, Mao TL, Nakayama N, Shih Ie M, Kurman RJ. Low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary displaying a macropapillary pattern of invasion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1800–6. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318181a7ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Iaco P, Ferrero A, Rosati F, Melpignano M, Biglia N, Rolla M, et al. Behaviour of ovarian tumors of low malignant potential treated with conservative surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:643–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurent I, Uzan C, Gouy S, Pautier P, Duvillard P, Morice P. Results after conservative treatment of serous borderline tumors of the ovary with a micropapillary pattern. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3561–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanat-Pektas M, Ozat M, Gungor T, Sahin I, Yalcin H, Ozdal B. Complete lymph node dissection: is it essential for the treatment of borderline epithelial ovarian tumors? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:879–84. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winter WE, 3rd, Kucera PR, Rodgers W, McBroom JW, Olsen C, Maxwell GL. Surgical staging in patients with ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:671–6. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longacre TA, McKenney JK, Tazelaar HD, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential (borderline tumors): outcome-based study of 276 patients with long-term (> or =5-year) follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:707–23. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000164030.82810.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang SJ, Ryu HS, Chang KH, Yoo SC, Yoon JH. Prognostic significance of the micropapillary pattern in patients with serous borderline ovarian tumors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:476–81. doi: 10.1080/00016340801995640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]