Abstract

All organisms must trade off resource allocation between different life processes that determine their survival and reproduction. Malaria parasites replicate asexually in the host but must produce sexual stages to transmit between hosts. Because different specialized stages are required for these functions, the division of resources between these life-history components is a key problem for natural selection to solve. Despite the medical and economic importance of these parasites, their reproductive strategies remain poorly understood and often seem counterintuitive. Here, we tested recent theory predicting that in-host competition shapes how parasites trade off investment in in-host replication relative to between-host transmission. We demonstrate, across several genotypes, that Plasmodium chabaudi parasites detect the presence of competing genotypes and facultatively respond by reducing their investment in sexual stages in the manner predicted to maximize their competitive ability. Furthermore, we show that genotypes adjust their allocation to sexual stages in line with the availability of exploitable red blood cell resources. Our findings are predicted by evolutionary theory developed to explain life-history trade-offs in more traditionally studied multicellular taxa and suggest that the answer to the long-standing question of why so few transmission stages are produced is that in most natural infections heavy investment in reproduction may compromise in-host survival.

Keywords: phenotypic plasticity, Plasmodium, transmission, survival, life history, trade-off

Introduction

Explaining variation in the life-history traits exhibited by individuals is a major aim in evolutionary biology. Life-history theory provides a solid foundation for understanding plasticity in resource allocation trade-offs and can be used to explain and predict the evolutionary consequences of environmental variation (Roff 1992; Stearns 1992). There is also increasing interest in using an evolutionary approach to understand how parasite life-history traits shape within-infection dynamics and contribute to virulence and transmission (e.g., Eisen and Schall 2000; Day 2003; Paul and Brey 2003; Paul et al. 2003; Foster 2005; Reece et al. 2009). For organisms such as malaria (Plasmodium) parasites, in which in-host replication and between-host transmission are achieved by different specialized stages, the division of resources between these life-history components is a key problem for natural selection to solve. This is analogous to the trade-off between reproduction and maintenance faced by multicellular sexually reproducing organisms (Koella and Antia 1995). The assumption that reproduction is costly, resulting in trade-offs between reproduction and survival and between current and future reproductive effort, is a key concept in evolutionary biology (Williams 1966).

Life-history theory has provided a wealth of predictions for how the best solutions to resource allocation trade-offs are influenced by the state of individuals and the environments they experience (Williams 1966; Roff 1992; Stearns 1992; Pigliucci 2001). However, precisely how individuals should adjust their allocation decisions when resources become scarce is unclear. A decrease in the availability of resources can select for increased investment in maintenance (survival), which is achieved by reducing reproductive effort (“reproductive restraint”; Fischer et al. 2009; McNamara et al. 2009). Conversely, reduced survival probability can favor increased investment in reproduction (in the extreme, “terminal investment”; Williams 1966; Charlesworth and Leon 1976; Fischer et al. 2009). These investment decisions may lie at opposite ends of a continuum, and whether individuals can adopt the best solution depends on the costs and constraints of plasticity and the accuracy of available information. Testing how individuals trade off investment between survival and reproduction has been constrained by difficulties in measuring reproductive effort for multicellular organisms (Clutton-Brock 1984; but see Creighton et al. 2009). Reproductive effort can be readily measured for malaria parasites; however, despite more than a century of research into interventions that block reproduction, their investment strategies remain poorly understood (Reece et al. 2009). Previous studies suggest that when in-host survival is threatened parasites increase investment in between-host transmission at the expense of in-host replication (Buckling et al. 1997, 1999b; Poulin 2003; Stepniewska et al. 2004; Bousema et al. 2008; Peatey et al. 2009), but recent evolutionary theory predicts that the opposite should occur (Mideo and Day 2008; Mideo 2009).

As a general rule, malaria parasites appear to invest remarkably little in transmission throughout infections (Taylor and Read 1997); explanations for this apparent reproductive restraint include reducing virulence experienced by vectors, minimizing the extent to which hosts develop transmission blocking immunity, and using numerically dominant asexual stages to shield transmission stages from attack by nonspecific immune factors (Taylor and Read 1997; McKenzie and Bossert 1998). However, recent formal theory predicts that within-host competition for resources alone can be sufficient to select for reproductive restraint (Mideo and Day 2008). Genetically mixed infections are common (Babiker et al. 1991; Mayxay et al. 2004; Vardo and Schall 2007), so parasites frequently interact with coinfecting genotypes (including con- and heterospecifics). That competition results in suppressed growth and transmission of coinfecting genotypes is well known, but the underlying contributions of exploitation (e.g., for red blood cell resources) and apparent (immunemediated) competition are unclear (Taylor et al. 1997a; Haydon et al. 2003; Mayxay et al. 2004; Bell et al. 2006; Råberg et al. 2006; Barclay et al. 2008). Theory predicts that parasites experiencing local competition (within the host) should divert investment away from reproduction to maximize their ability to replicate and thus exploit the greatest share of red blood cell resources. The recent discovery that malaria parasites can detect and respond to the presence of unrelated competitors (Reece et al. 2008) suggests that they could also use this information to decide how much to invest in reproduction. Previous attempts to test this prediction have been inconclusive (Taylor et al. 1997b; Wargo et al. 2007b; Bousema et al. 2008), but these studies did not consider patterns of reproductive effort or performance of focal genotypes in mixed infections.

Here, we used several genotypes of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi to test whether parasites facultatively respond to in-host competition by decreasing their investment in between-host transmission. We investigated how competition, resource availability, and genetic variation interact to shape patterns of investment in gametocytes during infections. First, we used a bank of genotypes to test for genetic variation in patterns of gametocyte investment throughout infections. Second, we monitored three focal genotypes in single and mixed infections with one or more competitors to test whether investment in gametocytes is facultatively reduced in competition. Third, we predicted that if reproductive restraint in mixed infections enables parasites to gain the greatest share of exploitable resources, then the investment decisions of each genotype will be influenced by the availability of these resources.

Methods

Infections and Experimental Design

We used Plasmodium chabaudi genotypes from the World Health Organization Registry of Standard Malaria Parasites (University of Edinburgh). These wild-type clonal genotypes were isolated from an area where mixed infections are frequent (Carter 1978). Infections described in this article were originally set up to examine sex ratios in single and mixed infections. Full details are available in Reece et al. (2008). Briefly, the treatment groups were as follows: (1) six groups of single-genotype infections, consisting of 1 × 106 AJ, AS, ER, CR, CW, or DK parasites; (2) two groups of two-genotype infections, one group with 1 × 106 AJ + 1 × 106 AS parasites and a second group with 1 × 106 AJ + 1 × 106 ER parasites; and (3) one group of three-genotype infections with 1 × 106 AJ + 1 × 106 AS + 1 × 106 ER parasites. Although the starting doses of parasites were higher in mixed infections than in single infections, the starting dose of each focal genotype was kept constant. This was necessary because comparing the behavior of genotypes in different scenarios requires initiating infections of focal genotypes in the same way and manipulating only the in-host environment they experience (i.e., the presence or absence of competition) for each treatment. Previous experiments have demonstrated that variation in the number of parasites initiating infections has negligible effects on infection dynamics. Specifically, varying starting densities from 1 × 102 to 1 × 108 parasites (for comparison, our infections varied from 1 × 106 to 3 × 106) had very little effect on asexual production during infections (Timms et al. 2001) and, more importantly, on gametocyte production (Timms 2001). Thus, our experimental design is standard in studies examining the effect of in-host competition in malaria (including de Roode et al. 2005a; Råberg et al. 2006; Reece et al. 2008; Wargo et al. 2007b) and has also been used for other systems (e.g., Balmer et al. 2009; Lohr et al. 2010). We used polymerase chain reaction assays (Drew and Reece 2007) to distinguish and quantify the asexual stages and gametocytes produced by each clone throughout infection. Our assays enabled us to monitor each competitor in the two-genotype infections, which maximized the power of our analyses while minimizing the number of mice required; however, because AS and ER cannot be distinguished, we monitored only AJ in three-genotype infections.

We used 6–8-week-old male MF1 mice (in-house supplier, University of Edinburgh), and all treatment groups contained five mice. Sampling was performed in the morning so that circulating parasites were in ring or earlytrophozoite stages and to obtain samples before DNA replication for the production of daughter progeny occurs. We restricted our analysis to data collected between patency of infection (day 5 postinfection [PI]) and day 12 PI because (1) it minimized the time for the development of strain-specific immunity (Quin and Langhorne 2001; Achtman et al. 2007) that might kill gametocytes and potentially confound estimates of parasite investment decisions; (2) it maximized power for the analysis, given that three mice in the treatment group with the most virulent strain combination (AJ + ER) died on day 12 PI; and (3) the effects of competition are strongest during the acute phase (Bell et al. 2006). Red blood cell densities were estimated using flow cytometry (Coulter Counter, Beckman Coulter; see Ferguson et al. 2003), and reticulocyte densities were estimated from thin blood smears. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Gametocyte Conversion Rate

Competitive suppression in mixed infections is well documented (Taylor et al. 1997a; Paul et al. 2002; de Roode et al. 2004b, 2005a, 2005b; Bell et al. 2006; Råberg et al. 2006) and results in a reduction in the densities of all competing genotypes (relative to those achieved in single infections). Because suppressed genotypes have a smaller pool of parasites from which to produce gametocytes, simply observing lower densities of gametocytes in mixed infections would not reveal whether parasites had invested a lower proportion of their number into developing as sexual stages. Similarly, variation in gametocyte density could be generated from the same relative level of investment by cohorts that simply differ in parasite number. Therefore, we calculated the conversion rate (following Buckling et al. 1999b), which is the standard method for measuring investment in sexual stages (gametocytes). The conversion rate represents the proportion of parasites in a given synchronous cohort that differentiate into sexual stages relative to asexual stages and takes into account the growth rate for each genotype and the time asexual stages and gametocytes take to mature (24 and 48 h, respectively) in our P. chabaudi model system.

Analyses

We used R software (version 2.6.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.R-project.org) for all analyses. We subjected conversion rates to arcsine square root transformation and performed analyses using linear mixed-effect models with mouse as a random effect to overcome pseudoreplication problems of repeated sampling of infections in each host. We followed model simplification by sequentially dropping the least significant term and comparing the change in deviance with and without the term to χ2 distributions until the minimal adequate model was reached. Degrees of freedom corresponded to the difference in the number of terms in the model. For analyses reported in “Resource Availability,” the density of available uninfected red blood cells was calculated by deducting the daily total parasite density from the corresponding daily density of red blood cells.

Results

Gametocyte Investment during Infections

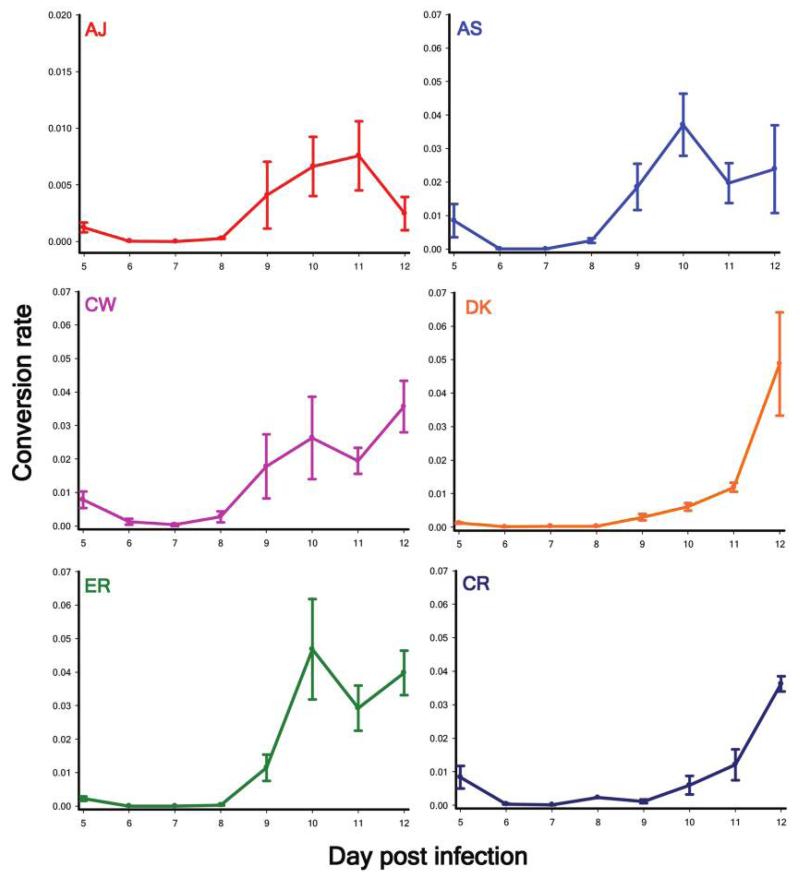

We monitored six wild-type genotypes (AS, AJ, ER, DK, CR, and CW) of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi to test whether there is within-species genetic variation for conversion rates during the acute stage of infection. Each genotype followed significantly different patterns of conversion across the course of its infections (genotype × day PI: , P < .0001; fig. 1). Genetic variation in a trait is required for selection to shape its expression and could reflect differences in resource acquisition abilities. Therefore, we tested whether conversion rates are related to the abundance and age of available red blood cell resources. The resources available to each parasite cohort explained significant variation in conversion rates, with positive correlations between conversion rate and red blood cell density for five of the six genotypes (, P = .039) and the proportion of red blood cells that were reticulocytes (young red blood cells; , P = .036) for all genotypes.

Figure 1. Genetic variation for investment in reproduction (transmission stages).

Shown is the production of gametocyte stages relative to asexual stages (conversion rate) for six wild-type Plasmodium chabaudi genotypes during the acute stage of infection. Error bars show the SEM for five independent infections per genotype.

Effect of Competition on Gametocyte Investment

We used three genotypes (AS, AJ, and ER) to test whether conversion rates are adjusted in response to competition. For each genotype, we compared the conversion rates produced in single infections to those produced in competition with different numbers of unrelated conspecifics. Because our quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays could distinguish AJ asexual stages and gametocytes from those of AS and ER but not between AS and ER (Drew and Reece 2007), we monitored AS and ER in double infections (each with AJ) and AJ in double and triple infections (with AS, ER, or both). The conversion rates produced by AJ did not significantly differ depending on the identity (day PI × competitor genotype: , P > .5) or number (day PI × competitor number: , P > .5) of coinfecting genotypes; therefore, we simplified our analysis to two treatment conditions, “alone” and “in competition,” for each of the three focal genotypes.

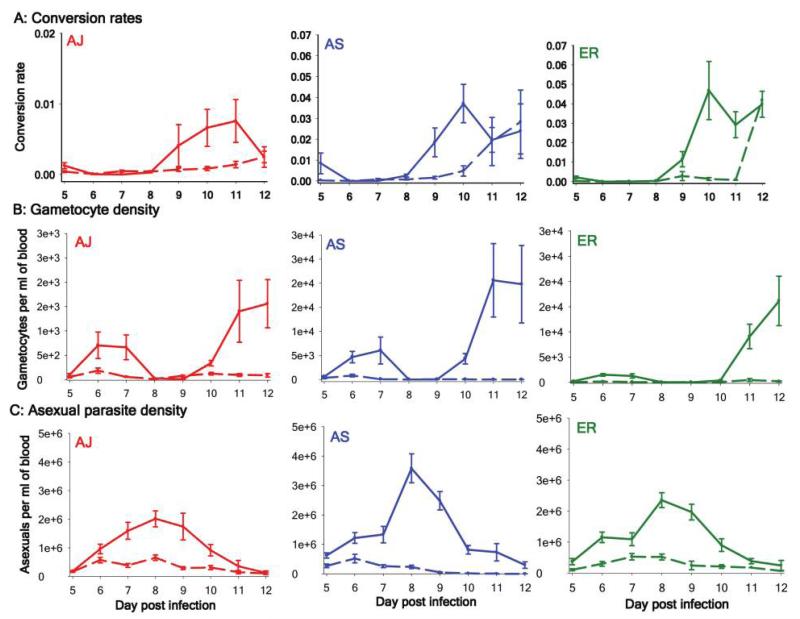

The existence of competitive suppression is required for our experimental manipulations, and the asexual densities for all focal genotypes were significantly reduced in mixed infections (genotype × day PI × treatment: , P < .0001; fig. 2C). As predicted, compared with their behavior in single infections (alone), all three genotypes significantly reduced their conversion rates in mixed infections (in competition), and the magnitude of this effect varied over the course of infections and between the genotypes (genotype × day PI × treatment: , P < .0005; fig. 2A). Lower gametocytes densities were also observed for each focal genotype in mixed infections (genotype × day PI × treatment: , P < .0001; fig. 2B). In addition to the effect of competition, conversion rates also had a significant negative correlation with the overall densities of parasites in infections (, P < .005), but there was no significant correlation between conversion rates and red blood cell density (, P = .87) or the proportion of red blood cells that were reticulocytes (, P = .11).

Figure 2. Analysis of competitive suppression.

Competitive suppression of parasites led to reduced investment in reproduction (transmission) and lower gametocyte density. Shown are the conversion rate (A), gametocyte density (B), and asexual parasite density (C) for three focal genotypes alone (solid lines) and in competition (dashed lines). Error bars show the SEM for between five and 15 independent infections per group.

Resource Availability

Because our single-infection data suggested that gametocyte investment is related to the availability of red blood cell resources but our competition data suggested that competition per se is more important, we investigated whether resources influence the strategies of competing parasites in more depth. We focused on the data from mixed infections to test whether the conversion rate for each parasite cohort correlated with the density of available red blood cells. Because we found no significant difference in the conversion rates for AJ and ER (, P > .1), we simplified our analysis to group these genotypes together. For all genotypes, there was a positive correlation between the density of available red blood cells and conversion rate, and this effect was greater for AS than for AJ/ER (genotype × resource availability: , P < .0005, AS estimated slope = 4.46 × 10−5 [±1.26 × 10−5], AJ/ER estimated slope = 4.08 × 10−6 [±5.42 × 10−7]).

Discussion

Testing the assumption that reproduction is costly and trades off against investment in survival is a challenge in evolutionary biology because of potentially confounding effects of differential survival of individuals that vary in quality, multiple components of reproductive investment (e.g., egg provisioning and parental care), decline through senescence, and performance improvement as individuals gain experience. Malaria parasites do not have these complexities and genotypes can be tested in different environments, thus providing a novel system with which to test life-history theory (Reece et al. 2009). Our analyses reveal significant patterns of genetic variation and phenotypic plasticity (figs. 1, 2) in the reproductive effort of malaria parasites. Our experiment also demonstrates, across several genotypes, that investment in gametocytes is facultatively reduced when parasites experience mixed infections (fig. 2) and that this response is influenced by resource availability.

Adopting a reproductive-restraint strategy in competition (fig. 2) is predicted to enable parasites to maximize their share of exploitable resources in mixed infections (Mideo and Day 2008). Despite the widespread occurrence of genetically mixed infections in natural populations, how in-host competition shapes plasticity in parasite life-history trade-offs is rarely considered (but see Wargo et al. 2007b). Parasites in mixed infections experience competitive suppression, which could be due to direct (exploitation) competition for resources such as red blood cells (Mideo and Day 2008) or to apparent competition in which the presence of another genotype results in cross-reactive immune responses that are damaging for both genotypes (McKenzie and Bossert 1998). Diverting investment away from gametocytes and into asexual replication, as observed in our experiment, benefits parasites experiencing both types of competition. The “safety in numbers” afforded by reproductive restraint may enable parasites to withstand attack from cross-reacting immune responses as well as maximize the ability to compete for resources. Interactions between these different forms of competition are well known in predator-prey ecology; the presence of a competitor can both reduce food availability and increase predator numbers (Holt 1977; Jones et al. 2009). Disentangling the relative influences of exploitation and apparent competition is challenging. Our experiment was not designed to test for apparent competition, but our mixed-infection data suggest that exploitation competition plays a role, given that conversion rates were positively correlated with the availability of red blood cell resources.

Reducing investment in gametocytes as a response to competition is predicted to maximize competitive ability, but the parasites in our experiment—like all other mixed-infection experiments with this model system—still experienced suppression (fig. 2C). Does this suggest that the parasites did not benefit from adopting reproductive restraint, or would they have been even more suppressed without this strategy? Quantifying the effects of reproductive restraint on competitive ability requires comparing the extent of suppression experienced by parasites that can and cannot reduce their gametocyte investment. Measuring the fitness consequences of investment decisions is difficult, but one way to achieve this would be through identifying the mechanism used to detect coinfecting competitors and manipulating parasites to be unable to respond. The costs and benefits of altering gametocyte investment will also depend on aspects of parasite ecology and population biology. For example, parasites restricted to infecting a specific age class of red blood cells may face more severe resource limitation in competition than do more generalist parasites (Reece et al. 2005). Resource limitation may occur during periods of anemia, but for parasites that can infect reticulocytes anemia may signal an imminent influx of resources, making reproductive restraint the best short-term solution. Another important aspect of the trade-off between current and future reproduction concerns opportunities for transmission to mosquitoes and the type of hosts to which parasites will be transmitted (Day 2002; Alizon and van Baalen 2008; Reece et al. 2009). For example, in-host survival may be sufficiently important to constrain gametocyte investment to low levels in areas with irregular or low transmission or if there is a high probability that the next host already harbors competing parasites (Vardo et al. 2007).

In contrast to our data, most previous studies have demonstrated that parasites do not adopt reproductive restraint when experiencing stress. For example, parasites are known to produce more gametocytes when exposed to subcurative doses of antimalarial drugs, anemia, or changes in the age of available red blood cells (Trager and Gill 1992; Buckling et al. 1997, 1999a; Reece et al. 2005). Most explanations assume that these changes in the in-host environment cause sufficient reduction in parasite survival to induce terminal investment in reproduction (Buckling et al. 1997, 1999a; Stepniewska et al. 2004; Peatey et al. 2009). However, reproductive restraint has now been observed in response to low doses of drugs (Reece et al. 2010), and the influx of reticulocytes during anemia may benefit parasites that can use this resource (Reece et al. 2005). Therefore, we suggest that changes in the in-host environment should be evaluated in the context of parasite ecology to interpret whether changes in gametocyte investment are due to reproductive restraint, terminal investment, or a response to increased resources. More broadly, the ability of parasites to fine tune gametocyte investment in response to subtle changes in their in-host environment highlights the importance of measuring and accounting for variation in these parameters when investigating the effects of experimental manipulations on parasite behavior.

Few studies (but see Buckling et al. 1999b; Wargo et al. 2007b) have formally tested whether genetic variation in patterns of gametocyte densities are due to different investment strategies or are simply by-products of variation in asexual stage densities. By using a bank of six genotypes and monitoring infections initiated with the same starting dose in immunologically naive hosts, we have demonstrated genetic variation in reproductive investment (fig. 1). The explanations for this variation are not yet known; investment patterns are not related to the virulence rankings of the genotypes (Mackinnon and Read 1999) or to competitive ability (Bell et al. 2006). Alternatively, there may be genetic variation for the range of red blood cell ages that parasites can invade and utilize (Antia et al. 2008; Mideo et al. 2008). However, while our data revealed that gametocyte investment is positively correlated with the abundance of mature and immature red blood cells, we did not find any G × E interactions for this pattern. Because Plasmodium chabaudi is in general able to infect all ages of circulating red blood cells, all genotypes may simply be able to afford greater investment in gametocytes when resources are abundant (Reece et al. 2005).

To investigate whether resource availability matters in competition, we focused only on the mixed infections and asked whether the conversion rates for each cohort correlated with the density of uninfected red blood cells. We predicted that gametocyte investment would be positively correlated with available resources. Data on all three of our genotypes (AS, AJ, and ER) supported this prediction and demonstrated genetic variation in these patterns because the slope for this correlation was greater for AS than for AJ and ER. Why this genetic variation exists is unclear, but it could be related to competitive ability given that AJ and ER are known to be superior competitors relative to AS (Bell et al. 2006). This could be tested by initiating infections with competing genotypes at different densities and frequencies in hosts with manipulated levels of anemia to span a broader range of competitive suppression and resource availability. Such experiments, ideally combined with modeling, could also reveal whether decisions span the continuum from reproductive restraint to terminal investment and how parasites respond to different stresses that affect the proliferation rate.

Explaining how parasites respond to changes in their in-host environment is important for understanding patterns of virulence and transmission. All else being equal, when parasites decrease investment in gametocytes, relatively more of the host-damaging asexual stages are produced. Thus, by most measures a strain that shifts investment away from gametocytes is likely to be more “virulent” (Mideo and Day 2008). In light of this, our results are also in agreement with a large body of theory on virulence evolution predicting that in mixed infections parasites are selected to become less prudent (Frank 1994, 1996). Furthermore, if medically relevant parasite species adopt reproductive restraint in response to in-host competition, selection could be strong enough to fix parasite investment in gametocytes at a low level where mixed infections are common. If so, these parasites would have a greater capacity to cause disease when released from competition—for example, as a result of evolving drug resistance and the removal of sensitive competitors by drug treatment (de Roode et al. 2004a; Wargo et al. 2007a).

Translating the results from our model system to human malaria parasites, especially Plasmodium falciparum, may be complicated by differences in the traits that underlie virulence. For example, in contrast to P. chabaudi, rosetting is a virulence trait in P. falciparum, but occurrence of this phenotype also correlates with parasitemia (Rowe et al. 2002). If P. falciparum responds to competition in the same way as P. chabaudi, we expect hosts to harbor infections made up of fewer gametocytes relative to asexual parasites in regions of endemicity, where mixed infections are frequent. There is some evidence that P. falciparum gametocyte densities are lower in areas of endemicity and in older individuals (Drakeley et al. 2006). A proposed explanation for these trends is that immunity develops more rapidly to gametocytes than to asexual stages and that stronger responses develop in areas of endemicity and in older patients (Drakeley et al. 2006). However, we suggest a possible alternative explanation—that infections in areas of endemicity and older hosts are more likely to contain a mixture of genotypes. Now that tools to measure genetic diversity in natural infections are available, it should be possible to test these hypotheses.

Reciprocal competitive suppression is well known in our rodent malaria system (Taylor et al. 1997a; Paul et al. 2002; de Roode et al. 2004b, 2005a, 2005b; Bell et al. 2006; Råberg et al. 2006), but interactions between coinfecting clones may be more complex in P. falciparum infection. Parasite interactions may span from facilitation (e.g., via changes in the age structure of red blood cells; McQueen 2006), to no effect on each other, to direct competition for resources (e.g., red blood cells; de Roode et al. 2005a), and these interactions can be intensified or alleviated by cross-reactive immune responses (Gupta et al. 1994; Gilbert et al. 1998; Barclay et al. 2008). For example, molecular data suggest that proportions of different clones within mixed infections can fluctuate over time, suggesting that multiple clones are not always present in the circulation (Babiker et al. 1998). This may also mean that whether a clone appears to be a good or a poor competitor is context dependent. Understanding these interactions in natural settings is a huge challenge, but given that there is much variation in the population ecology of human malaria parasites, they offer an attractive system for the study of mixed infections.

In conclusion, the gametocyte investment patterns we observed are predicted by evolutionary theory for life histories and demonstrate that parasites alter their investment in in-host replication (survival) relative to that in between-host transmission (reproduction) in response to competition. That competitive ability and resource abundance also mediate this trade-off adds considerable support to the hypothesis that parasites evaluate their social and in-host environments and respond adaptively (Reece et al. 2009). Our findings also suggest that the answer to the long-standing question of why so few transmission stages are produced (Taylor and Read 1997) is that in most natural infections the importance of investing in within-host survival constrains parasites to low investment in reproduction. The extent to which individuals display phenotypic plasticity in their reproductive effort depends on the fitness benefits of different life-history strategies, the costs and limits of assessing the relevant environmental or internal parameters, and constraints on the range of investment strategies that can be adopted (de Witt et al. 1998). If the proximate mechanisms underlying phenotypic plasticity in malaria parasites can be identified, it may be possible to manipulate their behavior in clinically and epidemiologically beneficial ways.

Malaria parasite transmission form in the blood.

Photograph by Sarah Reece.

Acknowledgements

We thank G. K. P. Barra and K. Fairlie-Clarke for discussion; A. Hayward, D. Nussey, and K. Stopher for statistical advice; W. Chadwick for technical assistance; and two anonymous reviewers for improving the manuscript. The Natural Environment Research Council, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Resource Council, and the Wellcome Trust funded the work.

Literature Cited

- Achtman AH, Stephens R, Cadman ET, Harrison V, Langhorne J. Malaria-specific antibody responses and parasite persistence after infection of mice with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Parasite Immunology. 2007;29:435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2007.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizon S, van Baalen M. Transmission-virulence trade-offs in vector-borne diseases. Theoretical Population Biology. 2008;74:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antia R, Yates A, de Roode JC. The dynamics of acute malaria infections. I. Effect of the parasite’s red blood cell preference. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;275:1449–1458. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiker HA, Creasey AM, Fenton B, Bayoumi RAL, Arnot DE, Walliker D. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum in a village in eastern Sudan. I. Diversity of enzymes, 2D-PAGE proteins and antigens. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1991;85:572–577. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90347-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiker HA, Abdel-Muhsin A, Ranford-Cartwright L, Satti G, Walliker D. Characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum parasites that survive the lengthy dry season in eastern Sudan where malaria transmission is markedly seasonal. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1998;59:582–590. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer O, Stearns SC, Schotzau A, Brun R. Intraspecific competition between co-infecting parasite strains enhances host survival in African trypanosomes. Ecology. 2009;90:3367–3378. doi: 10.1890/08-2291.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay VC, Råberg L, Chan BHK, Brown S, Gray D, Read AF. CD4+ T cells do not mediate within-host competition between genetically diverse malaria parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;275:1171–1179. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AS, de Roode JC, Sim D, Read AF. Within-host competition in genetically diverse malaria infections: parasite virulence and competitive success. Evolution. 2006;60:1358–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousema JT, Drakeley CJ, Mens PF, Arens T, Houben R, Omar SA, Gouagna LC, Schallig H, Sauerwein RW. Increased Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte production in mixed infections with P. malariae. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2008;78:442–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckling AG, Taylor LH, Carlton JM, Read AF. Adaptive changes in Plasmodium transmission strategies following chloroquine chemotherapy. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1997;264:553–559. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckling A, Ranford-Cartwright LC, Miles A, Read AF. Chloroquine increases Plasmodium falciparum gametocytogenesis in vitro. Parasitology. 1999a;118:339–346. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099003960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckling A, Crooks L, Read A. Plasmodium chabaudi: effect of antimalarial drugs on gametocytogenesis. Experimental Parasitology. 1999b;93:45–54. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. Studies on enzyme variation in murine malaria parasites Plasmodium berghei, P. Yoelii, P. vinckei and P. chabaudi by starch-gel electrophoresis. Parasitology. 1978;76:241–267. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000048137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B, Leon JA. The relation of reproductive effort to age. American Naturalist. 1976;110:449–459. [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T. Reproductive effort and terminal investment in iteroparous animals. American Naturalist. 1984;123:212–229. [Google Scholar]

- Creighton JC, Heflin ND, Belk MC. Cost of reproduction, resource quality, and terminal investment in a burying beetle. American Naturalist. 2009;174:673–684. doi: 10.1086/605963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day T. The evolution of virulence in vector-borne and directly transmitted parasites. Theoretical Population Biology. 2002;62:199–213. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2002.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day T. Virulence evolution and the timing of disease life-history events. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2003;18:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- de Roode JC, Culleton R, Bell AS, Read AF. Competitive release of drug resistance following drug treatment of mixed Plasmodium chabaudi infections. Malaria Journal. 2004a;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roode JC, Culleton R, Cheesman SJ, Carter R, Read AF. Host heterogeneity is a determinant of competitive exclusion or coexistence in genetically diverse malaria infections. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2004b;271:1073–1080. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roode JC, Helinski ME, Anwar MA, Read AF. Dynamics of multiple infection and within-host competition in genetically diverse malaria infections. American Naturalist. 2005a;166:531–542. doi: 10.1086/491659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roode JC, Pansini R, Cheesman SJ, Helinski MEH, Huijben S, Wargo AR, Bell AS, Read AF. Virulence and competitive ability in genetically diverse malaria infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2005b;102:7624–7628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500078102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Witt TJ, Sih A, Wilson DS. Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1998;13:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakeley C, Sutherland C, Bousema JT, Sauerwein RW, Targett GA. The epidemiology of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes: weapons of mass dispersion. Trends in Parasitology. 2006;22:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew DR, Reece SE. Development of reverse-transcription PCR techniques to analyse the density and sex ratio of gametocytes in genetically diverse Plasmodium chabaudi infections. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2007;156:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen RJ, Schall JJ. Life history of a malaria parasite (Plasmodium mexicanum): independent traits and basis for variation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2000;267:793–799. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson HM, MacKinnon MJ, Chan BH, Read AF. Mosquito mortality and the evolution of malaria virulence. Evolution. 2003;57:2792–2804. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Taborsky B, Dieckmann U. Unexpected patterns of plastic energy allocation in stochastic environments. American Naturalist. 2009;173:E108–E120. doi: 10.1086/596536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KR. Hamiltonian medicine: why the social lives of pathogens matter. Science. 2005;308:1269–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1108158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SA. Kin selection and virulence in the evolution of protocells and parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1994;258:153–161. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SA. Models of parasite virulence. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1996;71:37–78. doi: 10.1086/419267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SC, Plebanski M, Gupta S, Morris J, Cox M, Aidoo M, Kwiatkowski D, Greenwood BM, Whittle HC, Hill AVS. Association of malaria parasite population structure, HLA, and immunological antagonism. Science. 1998;279:1173–1177. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SC, Swinton J, Anderson RM. Theoretical studies of the effects of heterogeneity in the parasite population on the transmission dynamics of malaria. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1994;256:231–238. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon DT, Matthews L, Timms R, Colegrave N. Top-down or bottom-up regulation of intra-host blood-stage malaria: do malaria parasites most resemble the dynamics of prey or predator? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2003;270:289–298. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt RD. Predation, apparent competition, and the structure of prey communities. Theoretical Population Biology. 1977;12:197–229. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(77)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TS, Godfray HCJ, van Veen FJF. Resource competition and shared natural enemies in experimental insect communities. Oecologia. 2009;159:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s00442-008-1247-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koella JC, Antia R. Optimal pattern of replication and transmission for parasites with two stages in their life cycle. Theoretical Population Biology. 1995;47:277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JN, Yin M, Wolinska J. Prior residency does not always pay off—co-infections in Daphnia. Parasitology. 2010;137:1493–1500. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon MJ, Read AF. Genetic relationships between parasite virulence and transmission in the rodent malaria Plasmodium chabaudi. Evolution. 1999;53:689–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb05364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayxay M, Pukrittayakamee S, Newton PN, White NJ. Mixed-species malaria infections in humans. Trends in Parasitology. 2004;20:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie FE, Bossert WH. The optimal production of gametocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1998;193:419–428. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara JM, Houston AI, Barta Z, Scheuerlein A, Fromhage L. Deterioration, death and the evolution of reproductive restraint in late life. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:4061–4066. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen PG, McKenzie FE. Competition for red blood cells can enhance Plasmodium vivax parasitemia in mixed-species malaria infections. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;75:112–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mideo N. Parasite adaptations to within-host competition. Trends in Parasitology. 2009;25:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mideo N, Day T. On the evolution of reproductive restraint in malaria. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2008;275:1217–1224. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mideo N, Barclay VC, Chan BHK, Savill NJ, Read AF, Day T. Understanding and predicting strain-specific patterns of pathogenesis in the rodent malaria Plasmodium chabaudi. American Naturalist. 2008;172:E214–E238. doi: 10.1086/591684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul REL, Brey PT. Malaria parasites and red blood cells: from anaemia to transmission. Molecules and Cells. 2003;15:139–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul REL, Nu VAT, Krettli AU, Brey PT. Interspecific competition during transmission of two sympatric malaria parasite species to the mosquito vector. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2002;269:2551–2557. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul REL, Ariey F, Robert V. The evolutionary ecology of Plasmodium. Ecology Letters. 2003;6:866–880. [Google Scholar]

- Peatey CL, Skinner-Adams TS, Dixon MWA, McCarthy JS, Gardiner DL, Trenholme KR. Effect of antimalarial drugs on Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;200:1518–1521. doi: 10.1086/644645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci M. Phenotypic plasticity: beyond nature and nurture. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin R. Information about transmission opportunities triggers a life-history switch in a parasite. Evolution. 2003;57:2899–2903. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quin SJ, Langhorne J. Different regions of the malaria merozoite surface protein 1 of Plasmodium chabaudi elicit distinct T-cell and antibody isotype responses. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69:2245–2251. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2245-2251.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Råberg L, de Roode JC, Bell AS, Stamou P, Gray D, Read AF. The role of immune-mediated apparent competition in genetically diverse malaria infections. American Naturalist. 2006;168:41–53. doi: 10.1086/505160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece SE, Duncan AB, West SA, Read AF. Host cell preference and variable transmission strategies in malaria parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2005;272:511–517. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece SE, Drew DR, Gardner A. Sex ratio adjustment and kin discrimination in malaria parasites. Nature. 2008;453:609–614. doi: 10.1038/nature06954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece SE, Ramiro RS, Nussey DH. Plastic parasites: sophisticated strategies for survival and reproduction? Evolutionary Applications. 2009;2:11–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece SE, Ali E, Schneider P, Babiker HA. Stress, drugs and the evolution of reproductive restraint in malaria parasites. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:3123–3129. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roff DA. The evolution of life histories: theory and analysis. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe JA, Obiero J, Marsh K, Raza A. Short report: positive correlation between rosetting and parasitemia in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2002;66:458–460. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns SC. The evolution of life histories. Oxford University Press; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Stepniewska K, Taylor WRJ, Mayxay M, Price R, Smithuis F, Guthmann JP, Barnes K, et al. In vivo assessment of drug efficacy against Plasmodium falciparum malaria: duration of follow-up. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48:4271–4280. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4271-4280.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LH, Read AF. Why so few transmission stages? reproductive restraint by malaria parasites. Parasitology Today. 1997;13:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)89810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LH, Walliker D, Read AF. Mixed-genotype infections of malaria parasites: within-host dynamics and transmission success of competing clones. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1997a;264:927–935. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LH, Walliker D, Read AF. Mixed-genotype infections of the rodent malaria Plasmodium chabaudi are more infectious to mosquitoes than single-genotype infections. Parasitology. 1997b;115:121–132. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timms R. The ecology and evolution of virulence in mixed infections of malaria parasites [PhD diss.] University of Edinburgh; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Timms R, Colegrave N, Chan BHK, Read AF. The effect of parasite dose on disease severity in the rodent malaria Plasmodium chabaudi. Parasitology. 2001;123:1–11. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001008083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W, Gill GS. Enhanced gametocyte formation in young erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Journal of Protozoology. 1992;39:429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1992.tb01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardo AM, Schall JJ. Clonal diversity of a lizard malaria parasite, Plasmodium mexicanum, in its vertebrate host, the western fence lizard: role of variation in transmission intensity over time and space. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:2712–2720. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardo AM, Kaufhold KD, Schall J. Experimental test for premunition in a lizard malaria parasite (Plasmodium mexicanum) Journal of Parasitology. 2007;93:280–282. doi: 10.1645/GE-1005R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargo AR, Huijben S, de Roode JC, Shepherd J, Read AF. Competitive release and facilitation of drug-resistant parasites after therapeutic chemotherapy in a rodent malaria model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2007a;104:19914–19919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707766104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wargo AR, de Roode JC, Huijben S, Drew DR, Read AF. Transmission stage investment of malaria parasites in response to in-host competition. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007b;274:2759–2768. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC. Adaptation and natural selection. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1966. [Google Scholar]