Abstract

Study Design

Retrospective analysis of radiological images.

Purpose

To determine the prevalence of lumbosacral transition vertebra (LSTV) and to study its significance with respect to clinically significant spinal symptoms, disc degeneration and herniation.

Overview of Literature

LSTV is the most common congenital anomaly of the lumbosacral spine. The prevalence has been debated to vary between 7% and 30%, and its relationship to back pain, disc degeneration and herniation has also not been established.

Methods

The study involved examining the radiological images of 3 groups of patients. Group A consisted of kidney urinary bladder (KUB) X-rays of patients attending urology outpatient clinic. Group B consisted of X-rays with or without magnetic resonance images (MRIs) of patients at-tending a spine outpatient clinic, and group C consisted of X-rays and MRI of patients who had undergone surgery for lumbar disc herniation. One thousand patients meeting the inclusion criteria were selected to be in each group. LSTV was classified by Castellvi's classification and disc degeneration was assessed by Pfirrmann's grading on MRI scans.

Results

The prevalence of LSTV among urology outpatients, spine outpatients and discectomy patients was 8.1%, 14%, and 16.9% respectively. LSTV patients showed a higher Pfirrmann's grade of degeneration of the last mobile disc. Results were found to be significant statistically.

Conclusions

The prevalence of LSTV in spinal outpatients and discectomy patients was significantly higher as compared to those attending the urology outpatient clinic. There was a definite causal relationship between the transitional vertebra and the degeneration of the disc immediately cephalad to it.

Keywords: Lumbosacral transitional vertebra, Castellvi's classification, Pfirrmann's grading, Spine outpatients, Urology outpatients, Discectomy patients

Introduction

Lumbosacral transition vertebra (LSTV) is the most common congenital anomaly of the lumbosacral spine and may manifest either as a sacral assimilation of the 5th lumbar vertebra (sacralisation) or separation of the 1st sacral vertebra into the lumbar spine (lumbarisation) [1,2]. The prevalence of LSTV is said to vary between 7% and 30% in various studies [3]. Apazidis et al. [4] studied kidney urinary bladder (KUB) radiographs of patients attending a urology clinic and described the prevalence of LSTV to be 35% in the American population. LSTV as a cause of low back pain was first described in 1917 as the Bartolotti syndrome [5]. However, its significance with respect to low back pain has been debated by several authors since then [6]. A causal relationship between LSTV and disc degeneration and herniation has also been not well established, with some authors reporting a higher rate of degeneration adjacent to the LSTV [7,8], while others [9-11] have reported no such association. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of LSTV and to study its significance with respect to clinically significant symptoms (low back pain and/or radicular leg pain), radiological disc degeneration and disc herniations.

Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a retrospective analysis of radiological images (X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) of 3 groups of patients.

1. Group A (urology outpatients)

This group consisted of the KUB X-rays of patients attending the urology outpatient department (OPD). It was ensured that each X-ray that was included showed adequate visualization of the following anatomical structures-the last thoracic vertebra with the attached rib, all the lumbar vertebrae including the transverse processes of the first and last lumbar vertebrae, sacrum and iliac crests. Patients with poor quality radiographs or where there was suboptimal visualization of all of the above-mentioned anatomical landmarks, as well as those with a visible pathological lesion in the lumbar spine were excluded. Patients with radiological records showing lumbar spinal imaging or OPD records showing a visit to the spinal OPD clinic were excluded from group A.

2. Group B (spine outpatients)

This group consisted of patients with X-rays with or without an MRI lumbosacral (LS) spine attending the spine OPD. Patients with poorly exposed films, films showing severe osteoporosis of the vertebra with biconvex disc spaces, vertebral destruction due to trauma/infection/tumor, postoperative changes such as a laminectomy defect, implants in situ, isthmic spondylolisthesis or spondylolysis, degenerative listhesis of grade 2 and above, deformities such as scoliosis, features suggestive of ankylosing spondylitis, and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, and those operated single level discectomy were excluded from group B.

3. Group C (discectomy patients)

This group consisted of X-rays and MRI LS spine of patients operated on for single level disc herniation of any of the last three mobile discs. Patients with multilevel disc herniation, high lumbar disc prolapse (above the third mobile disc), canal stenosis without disc prolapse, or with any other pathological condition in the adjacent levels such as tumor or infection were excluded.

The numbering of the lumbar vertebrae was done according to the method described by Bron et al. [1]. According to this method, a vertebra showing the presence of an attached rib, either fully formed or rudimentary, was considered to be the last thoracic vertebra, and the next caudal vertebra was named the first lumbar vertebra. The intercristal line on the antero-posterior radiograph of the lumbar spine was considered to correspond to the L4-L5 disc space, as described by Chakraverty et al. [12]. An upward and laterally directed transverse process was considered to belong to a thoracic vertebra, whereas a horizontally directed transverse process was considered to belong to a lumbar vertebra. The lumbar vertebra with the longest transverse process was considered as the third lumbar vertebra.

Based on these anatomical characteristics, we defined "lumbarisation of S1" as the presence of 5 distinct lumbar vertebrae with the transverse process of the first sacral vertebra either fusing with or forming a pseudarthrosis with the sacral ala. "Sacralization of L5" was said to occur when the transverse process of the last lumbar vertebra formed either a bony bridge or a pseudarthrosis with the sacral ala. The morphological type of LSTV was identified based on Castellvi's classification (Fig. 1) [1]. Castellvi's type I has been considered a variation of normal due to the presence of a mobile disc caudal to the vertebra in question and so was not called a transitional vertebra in our study. The last three mobile discs were numbered M1, M2, and M3 from a caudal to cephalad direction (Fig. 2). The presence of 4 or 6 lumbar vertebrae without a bony fusion or pseudoarthrosis at the last lumbar vertebra was considered as a thoracolumbar transition and these patients was excluded from the study (Fig. 3).

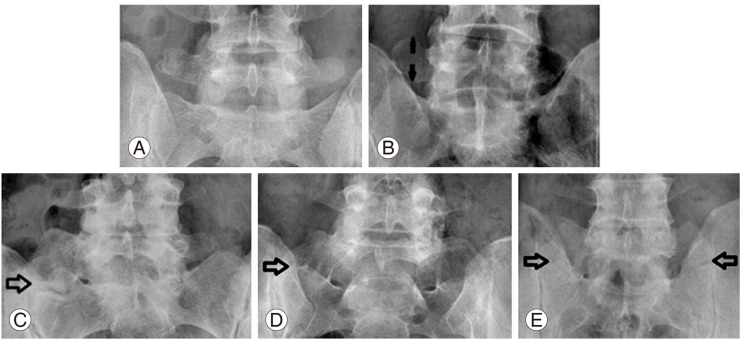

Fig. 1.

Castellvi's types of lumbosacral transition vertebra (LSTV). (A) X-ray showing normal lumbosacral spine (non-LSTV). (B) X-ray showing type Ib LSTV. Type I: dysplastic transverse process with a width more than 19 mm. Unilateral (type Ia) and bilateral (type Ib). (C) X-ray showing type IIa LSTV. Type II: presence of pseudoarthosis between the transverse process and ala of the sacrum. Unilateral (type Ia) and bilateral (type Ib). (D) X-ray showing type IIIb LSTV. Type III: presence of bony fusion between transverse process and ala of sacrum. Unilateral (type Ia) and bilateral (type Ib). (E) X-ray showing type IV. Type IV: presence of pseudoarthrosis on one side and bony fusion on the other.

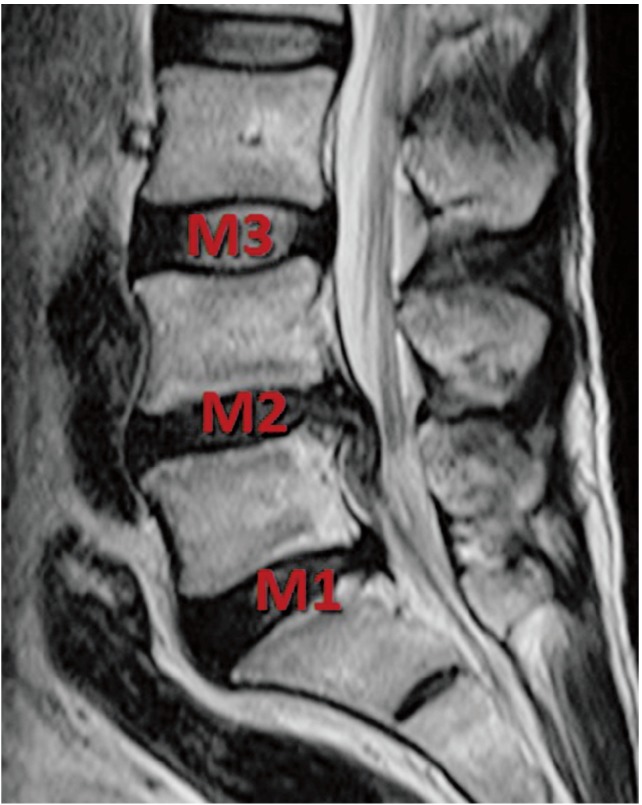

Fig. 2.

Labelling of mobile discs from caudal to cephalad as M1, M2, and M3.

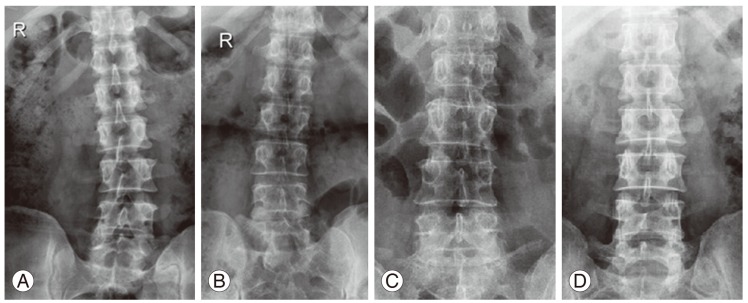

Fig. 3.

X-rays showing lumbosacral transitional vertebrae sacralisation (A), lumbarisation and thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae (B), 4 lumbar vertebrae (C), and 6 lumbar vertebrae (D).

Demographic data (age and sex), the presence of LSTV in the radiographic images and its type was recorded in all the 3 groups. Among the patients in group B who also had an MRI, disc degeneration was assessed by Pfirrmann's grading system (Fig. 4) [13]. Similar grading of disc degeneration was done in group C at the non herniated levels, i.e., if M1 was the herniated level, Pfirrmann's grading was assigned to the discs at the M2 and M3 levels. Based on this system, degeneration was graded as 'normal' (Pfirrmann's grade I), 'mild' (Pfirrmann's grade II) and 'advanced' (grades III-V). This was based on Lam et al. [14]'s findings of a positive provocative discography in 0%, 9%, and 71% of patients with Pfirrmann's grades I, II, III respectively and 100% in patients with Pfirrmann's grade IV and V. Lam et al. [14] stated that Pfirrmann's grading correlated strongly with the clinical symptoms.

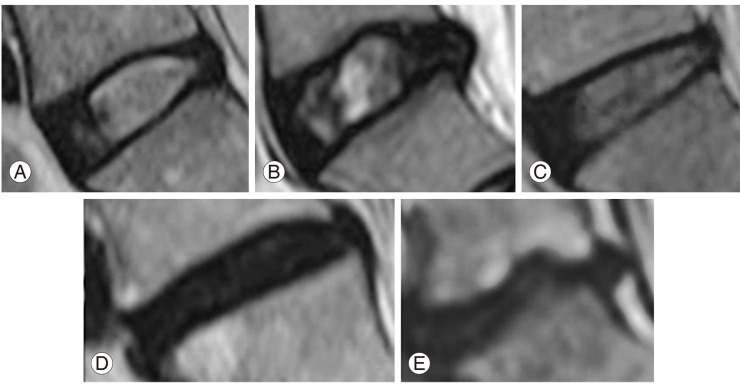

Fig. 4.

Pfirrmann's grading of disc degeneration on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image. (A) Grade 1: nucleus appears homogenously white, disc height is preserved, clear distinction between nucleus and annulus. (B) Grade 2: similar to grade 1 except for some signal intensity changes in the nucleus like horizontal clefts. (C) Grade 3: nucleus appears gray, disc height preserved or slightly reduced, distinction between nucleus and annulus is unclear. (D) Grade 4: nucleus appears black, with moderate reduction in the disc height without any distinction between nucleus and annulus. (E) Grade 5: completely collapsed homogenously black disc.

Radiological images of 1,000 consecutive patients meeting the inclusion criteria were selected for each group retrospectively from the hospital's OPD and operation records. The sample size of 3,000 was calculated from a similar study by Kong et al. [11], in which they found no significant difference between the LSTV and non-LSTV groups in degenerative spondylolisthesis patients, with a p-value of 0.8 and a sample size of 78, using "the N master software." In order to maintain consistency and avoid inter-observer variability, all the observations, classifications and grading were done by a single qualified spinal surgeon. The study was conducted in a major tertiary care centre with a daily OPD input of 6,000 patients including all specialities. The chi-square and proportion tests were used to compare 2 sets of variables and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was done using 'The R statistical software' by a qualified statistician. Probability and relative risks were also calculated using the same software.

Results

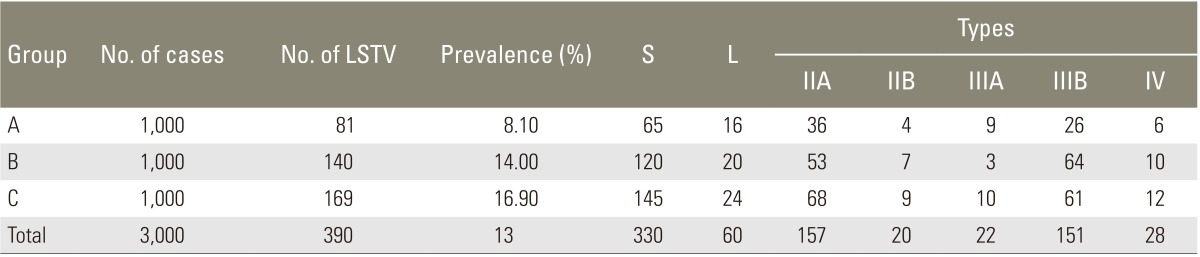

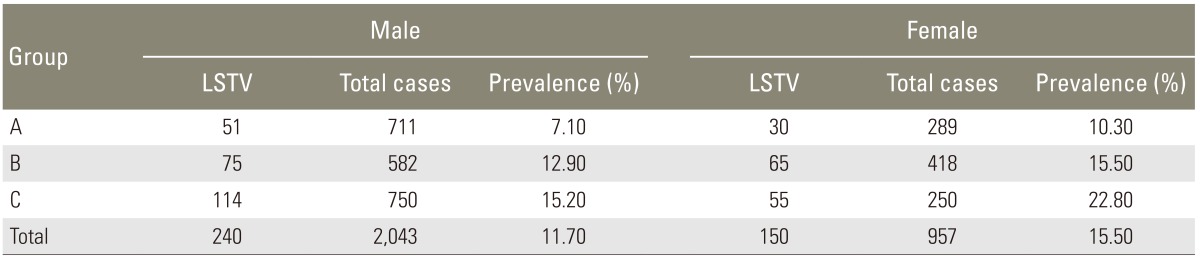

The prevalence of LSTV in groups A, B, and C was 8.1%, 14%, and 16.9% respectively, with an overall prevalence of 13% (Table 1). The type IIA pattern was found to be the commonest followed by type IIIB. The prevalence of LSTV in groups B and C was found to be significantly higher than in group A (p<0.001). The overall prevalence of sacralization was 11% and lumbarisation was 2%. The prevalence of LSTV was higher in females in all the 3 groups by about 1.3 times compared to males (Table 2).

Table 1.

Number of cases and prevalence of LSTV in each group

LSTV, lumbosacral transition vertebra; S, sacralised lumbar vertebra; L, lumbarailsed sacrum.

Table 2.

Sex specific prevalence of LSTV in each group

LSTV, lumbosacral transition vertebra.

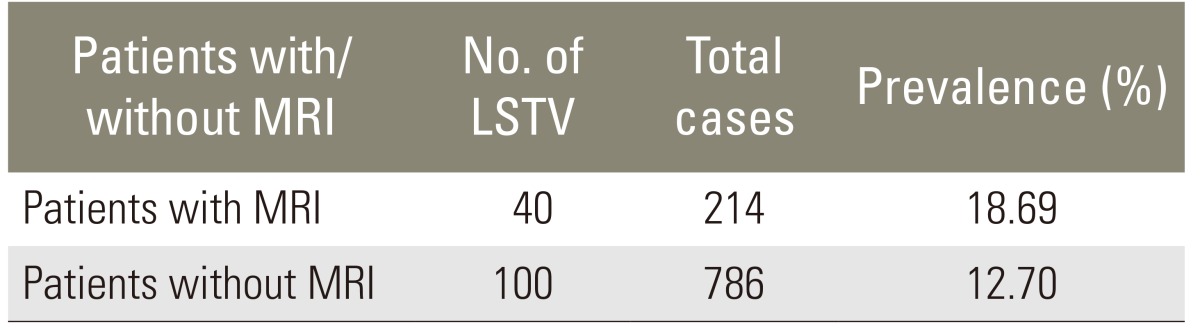

Among the total of 1,000 patients in group B, there were 786 patients who only had X-rays and 214 patients with both X-rays and MRIs. The prevalence of LSTV in these two groups was found to be 12.7% and 18.7%, respectively (Table 3), a difference that was statistically significant (p=0.025), indicating that LSTV was more likely to be encountered in patients symptomatic enough to require MRI scanning.

Table 3.

Number of cases and prevalance of LSTV among patients who had X-ray alone and those who had X-ray and MRI both

LSTV, lumbosacral transition vertebra; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

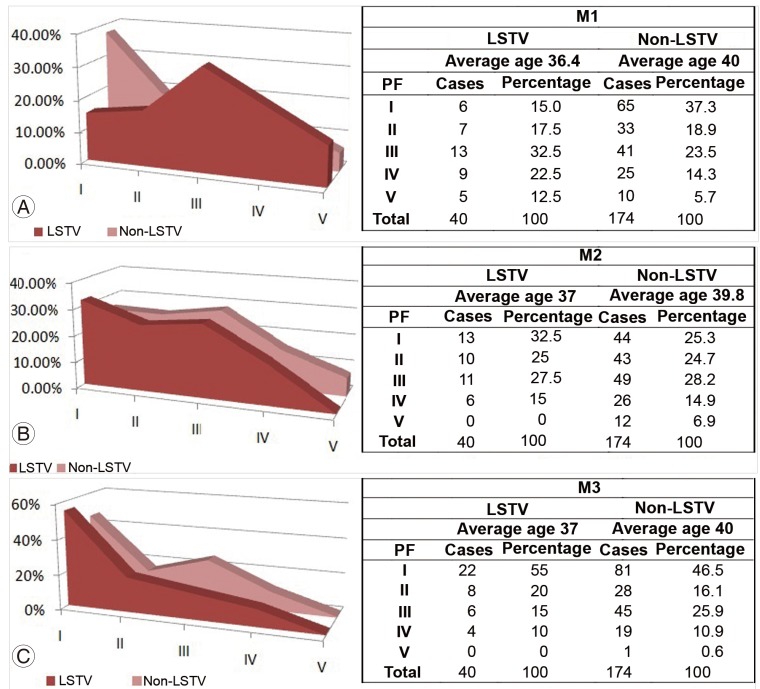

Among the 214 patients who had an MRI, we compared Pfirrmann's grading between the LSTV and non-LSTV groups at M1, M2 and M3 separately (Fig. 5). At M1, the LSTV group had significantly advanced degeneration (Pfirrmann's grades 3-5) as compared to non-LSTV patients (p=0.003). The corresponding degeneration patterns at the M2 and M3 levels did not show statistical differences between the LSTV and non-LSTV groups.

Fig. 5.

Comparison between number of cases and percentage of each Pfirrmann's grade (PF) in lumbosacral transition vertebra (LSTV) and non-LSTV groups at M1 (A), M2 (B), and M3 (C), with area diagram depicting the same group B. M1 showing greater degeneration in the LSTV groups with the M2 and M3 levels showing a similar pattern between the LSTV and non-LSTV groups.

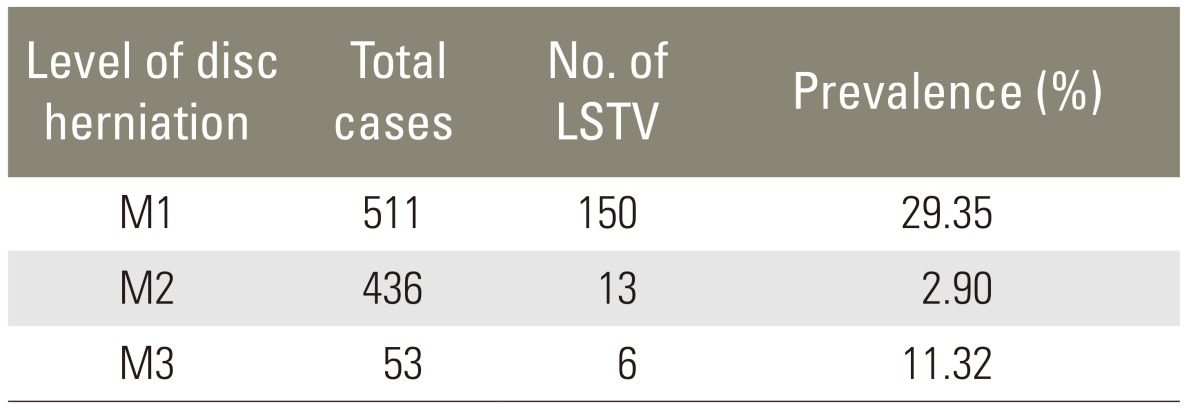

In group C, we assessed the prevalence of LSTV in patients who had undergone single-level disc surgery at M1, M2, or M3 levels separately, and found the prevalence to be 29.4%, 2.9% and 11.3% respectively (Table 4). The prevalence of LSTV in this group (group C) at each level (M1, M2, and M3) was compared with those of group A using the proportion test. At M1, the prevalence was significantly higher, and at M2, it was significantly lower, with a p-value of less than 0.001, and there was no difference at M3.

Table 4.

Prevelance of LSTV in patients with disc herniation at M1, M2, and M3 in group C

LSTV, lumbosacral transition vertebra.

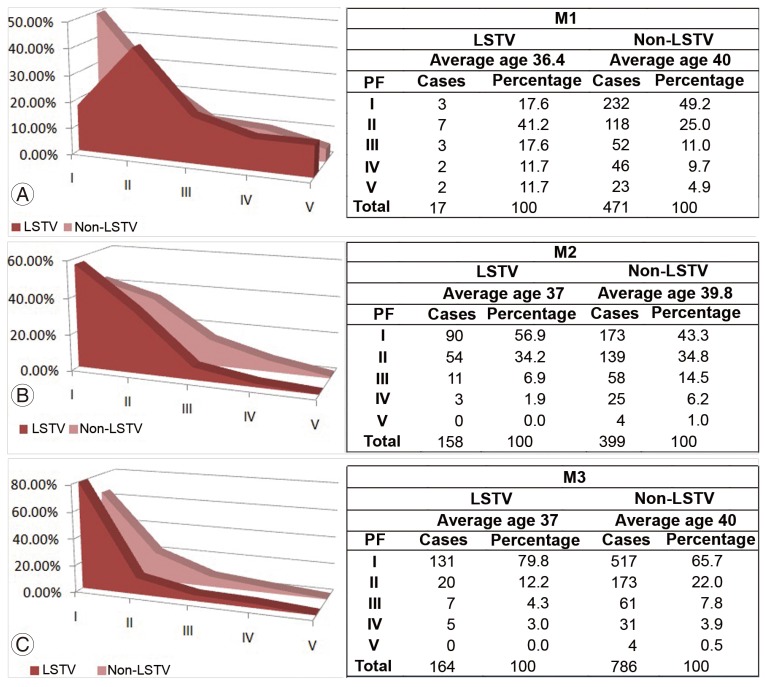

Finally, we assigned Pfirrmann's grade to the non-herniated discs in all of the 1,000 patients in group C; i.e., if the herniation was at M1, then Pfirrmann's grade of M2 and M3 were recorded. We then compared Pfirrmann's grading between the LSTV and non-LSTV groups at each level (M1, M2, and M3) separately, as was previously done for group B (Fig. 6). The pattern of Pfirrmann's grading between the LSTV and non-LSTV groups were similar to that in group B. At M1, the LSTV group had a significantly higher prevalence of mild and advanced degeneration as compared to the non-LSTV group (p=0.017 and p=0.02). At M2 there was an equal incidence of mild degeneration in both groups, but the LSTV group had significantly less advanced degeneration as compared to the non-LSTV group (p=0.001). At M3, the LSTV group had a significantly lower prevalence of mild as well as advanced degeneration as compared to the non-LSTV group (p=0.002 and p=0.025, respectively).

Fig. 6.

Comparison between number of cases and percentage of each Pfirrmann's grade of the discs at the non herniated levels (PF) in the lumbosacral transition vertebra (LSTV) and non-LSTV groups at M1 (A), M2 (B), and M3 (C), with an area diagram depicting the same in group C. M1 showing greater degeneration in the LSTV groups with the M2 and M3 levels showing a similar pattern between the LSTV and non-LSTV groups.

Discussion

Our study showed a statistically significant higher prevalence of LSTV among spinal OPD patients and discectomy patients as compared to urology OPD patients. However, group A, consisting of patients attending the urology OPD, may not be representative of the general or purely asymptomatic population. But when this group was considered as a whole, patients were definitely was less symptomatic with respect to the back than group B, as all the patients in group B were symptomatic and hence had consulted the spinal OPD. Moreover, estimating the prevalence in purely asymptomatic people would involve exposing otherwise healthy people to harmful radiation, which would be unethical and unacceptable. The method of using KUB X-rays has been employed by other authors such as Apazidis et al. [4], whose study is described in the literature. For these reasons, group A would be the best possible group, although not ideal, to serve as a control for comparison with symptomatic spinal outpatients and patients in the discectomy groups.

The fact that spine imaging studies are undertaken in our outpatient clinic, not as a routine but only in the presence of any red flags such as extremes of age, daily activities affected, presence of constitutional symptoms, persistent pain not relieved with medication, indicated that group B represented a population with clinically significant spinal symptoms. The subgroup of patients in group B who had both X-ray and MRI done were even more representative of the population with clinically significant symptoms, as their symptoms were severe enough to warrant an expensive investigation such as MRI. Our study showed a statistically significant higher prevalence of LSTV in this subgroup as well, when compared to group A or the subgroup of group B who had X-ray alone.

Statistically, the probability or the relative risk of finding a transitional vertebra in a patient with clinically significant spinal symptoms would be 1.75 times higher than in patients attending a urology OPD with non-spinal complaints. This probability would increase to 2.3 times among patients with symptoms severe enough to require an MRI and increase to 3.6 times among patients with last mobile disc herniation requiring discectomies.

Based on these observations, it is possible to conclude that LSTV is more like to be seen in patients with clinically significant spinal symptoms and even more so in those operated on for disc herniation of the last mobile disc. However, whether LSTV is the cause of the spinal symptoms or disc herniation could not be established by this study, but it does give a hint as to the direction further investigations should take.

The degree of discal degeneration on MRI showed distinctly different patterns in the LSTV and non-LSTV groups. Advanced discal degeneration (Pfirmann's grades 3-5) at the level supra-adjacent to the LSTV (i.e., at M1) was encountered significantly more commonly in the LSTV group (p=0.003). From these results, our study established a definite causal relationship between the transitional vertebra and degeneration of the disc immediately cephalad to it. The most likely explanation for this is that the motion segment cephalad to the LSTV has to bear additional stresses by virtue of it being juxtaposed to a relatively non-mobile segment, with the stresses borne by it similar to the stresses encountered by a disc adjacent to a mono-segmental fusion. The fact that discal degeneration at levels further cephalad (M2 and M3) showed a similar pattern in both the LSTV and non-LSTV groups further strengthens this argument.

Conclusions

The prevalence of LSTV in urology outpatients, spinal outpatients and discectomy patients was 8%, 14%, and 17% respectively, with an overall prevalence of 13%. Females had about 1.3 times higher prevalence of LSTV as compared to males. Almost 30% of patients operated on for symptomatic last mobile disc herniation had LSTV. The probability of finding LSTV in patients with clinical symptoms requiring an X-ray, those requiring an MRI and those requiring surgery for last mobile disc herniation was 1.75, 2.3, and 3.6 times higher respectively than those attending a urology OPD with non spinal symptoms. There was a definite causal relationship between the transitional vertebra and degeneration of the disc immediately cephalad to it. Whether this is the cause of spinal symptoms and last mobile disc herniations in people with transitional vertebra requires further study.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Bron JL, van Royen BJ, Wuisman PI. The clinical significance of lumbosacral transitional anomalies. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73:687–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konin GP, Walz DM. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: classification, imaging findings, and clinical relevance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1778–1786. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delport EG, Cucuzzella TR, Kim N, Marley J, Pruitt C, Delport AG. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: incidence in a consecutive patient series. Pain Physician. 2006;9:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apazidis A, Ricart PA, Diefenbach CM, Spivak JM. The prevalence of transitional vertebrae in the lumbar spine. Spine J. 2011;11:858–862. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida DB, Mattei TA, Soria MG, et al. Transitional lumbosacral vertebrae and low back pain: diagnostic pitfalls and management of Bertolotti's syndrome. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2009;67:268–272. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olofin MU, Noronha C, Okanlawon A. Incidence of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae in low back pain patients. West Afr J Radiol. 2001;8:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aihara T, Takahashi K, Ogasawara A, Itadera E, Ono Y, Moriya H. Intervertebral disc degeneration associated with lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: a clinical and anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:687–691. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.15727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luoma K, Vehmas T, Raininko R, Luukkonen R, Riihimaki H. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra: relation to disc degeneration and low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:200–205. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000107223.02346.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paajanen H, Erkintalo M, Kuusela T, Dahlstrom S, Kormano M. Magnetic resonance study of disc degeneration in young low-back pain patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14:982–985. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198909000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wigh RE, Anthony HF., Jr Transitional lumbosacral discs. probability of herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981;6:168–171. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong CG, Park JS, Park JB. Sacralization of L5 in radiological studies of degenerative spondylolisthesis at L4-L5. Asian Spine J. 2008;2:34–37. doi: 10.4184/asj.2008.2.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakraverty R, Pynsent P, Isaacs K. Which spinal levels are identified by palpation of the iliac crests and the posterior superior iliac spines? J Anat. 2007;210:232–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1873–1878. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam K, Anbar A, O'Brien A. The correlation of the severity of lumbar disc degeneration with discogenic low back pain: a study utilizing a validated classification with awake provocative discography. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(Suppl 4):566. [Google Scholar]