Abstract

Objectives

The present study sought to assess the relationship between depressive symptomatology and resilience among women infected with HIV and to investigate whether trauma exposure (childhood trauma, other discrete lifetime traumatic events) or the presence of post-traumatic stress symptomatology mediated this relationship.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Western Cape, South Africa.

Participants

A convenience sample of 95 women infected with HIV in peri-urban communities in the Western Cape, South Africa. All women had exposure to moderate-to-severe childhood trauma as determined by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We examined the relationship between depressive symptomatology and resilience (the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale) and investigated whether trauma exposure or the presence of post-traumatic stress symptomatology mediated this relationship through the Sobel test for mediation and PLS path analysis.

Results

There was a significant negative correlation between depressive symptomatology and resilience (p=<0.01). PLS path analysis revealed a significant direct effect between depression and resilience. On the Sobel test for mediation, distal (childhood trauma) and proximal traumatic events did not significantly mediate this association (p=> 0.05). However, post-traumatic stress symptomatology significantly mediated the relationship between depression and resilience in trauma-exposed women living with HIV.

Conclusions

In the present study, higher levels of resilience were associated with lower levels of self-reported depression. Although causal inferences are not possible, this suggests that in this sample, resilience may act as protective factor against the development of clinical depression. The results also indicate that post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), which are highly prevalent in HIV-infected and trauma exposed individuals and often comorbid with depression, may further explain and account for this relationship. Further investigation is required to determine whether early identification and treatment of PTSS in this population may ameliorate the onset and persistence of major depression.

Keywords: Psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study investigating the relationship between depressive symptomatology and resilience in a sample of trauma-exposed individuals infected with HIV and to find evidence of a mediating effect of post-traumatic symptoms on this relationship.

Potential recall bias on the retrospective rating scales may influence the findings.

The cross-sectional study design precludes causal inferences and longitudinal assessment of this relationship is necessary.

Background

In South Africa, an estimated 5.63 million individuals are infected with HIV. Of these, 3.3 million are women.1 High rates of intimate partner violence, rape and childhood abuse have been reported.2–4 Studies suggest high rates of childhood emotional (51.9%), physical (51.1%) and sexual (41.6%) abuse in HIV-positive individuals.5 HIV has become a manageable chronic disease with the increased use of highly active antiretroviral therapies (HAART). However, this chronicity is coupled with an increase in the number of lifetime emotional and physical challenges faced by infected individuals.6 Common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety are highly prevalent and comorbid with HIV/AIDS. Compared to the general population and comparable HIV-negative individuals, evidence suggests that the prevalence of depression is twofold to fourfold higher in individuals infected with HIV.7–10 Prevalence rates of depression in HIV-positive individuals range from 5% to 20% across a majority of studies.11 In South African studies, high rates of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been reported among individuals infected with HIV.12–16 The most commonly reported psychiatric disorders among HIV-positive individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment include substance abuse, major depressive disorder and PTSD.17 Research shows that childhood abuse and exposure to other traumas are among the risk factors for the development of adult psychopathology.18–22 However, not every individual who experiences early life stress or other traumatic incidents will develop a psychiatric disorder, highlighting the importance of resilience.23 24 Human responses to stress and trauma differ widely. Some individuals develop psychiatric disorders, such as PTSD and depression; others develop psychological symptoms that resolve rapidly, while others report no symptoms in response to traumatic stress.25 Numerous risk and protective factors, including developmental, cognitive, psychological (eg, personality traits, coping style, social support) genetic, epigenetic and neurobiological (neurochemistry and neural circuitry) mechanisms, have been shown to play a role in how individuals respond to stress and trauma.25 26 Resilience is a multidimensional construct and is understood as an individual's ability to bounce back from hardship and trauma.25 Resilience refers to a person's ability to adapt successfully to acute stress, trauma or more chronic forms of adversity.24 Resilience represents the personal qualities that enable one to thrive in the face of adversity.27 Resilience may be viewed as a measure of stress coping ability and, as such, could be an important target of treatment in anxiety, depression and stress reactions.27 However, there is relatively little awareness about resilience and its relationship to these disorders. In non-HIV samples, traumatic experiences such as childhood maltreatment and adult life stress, have been reported, among depressed patients, to influence treatment response.28 29 In patients with PTSD, high resilience has been associated with favourable treatment outcomes.30 Recent data also indicate that in depressed patients resilience contributes to more favourable treatment outcomes with the effects of resilience even more definitive when combined with low trait anxiety.31

To our knowledge, there are no studies investigating the relationship between depressive symptomatology and resilience in a sample of trauma-exposed individuals infected with HIV. In light of this, the present study sought to examine this relationship in a sample of trauma-exposed women infected with HIV.

Methods

Participants

A total of 230 women infected and uninfected with HIV, with and without trauma exposure consented to participate and were enrolled into a larger prospective cognitive and imaging study. Of these, 95 HIV-positive women had exposure to childhood trauma as defined on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and were included in the present study. A score of 41 and higher on the CTQ was used as the cut-off for exposure to childhood trauma. Eligibility criteria included willingness and ability to provide written informed consent, ability to read and write in either English or Afrikaans at 5th grade level, aged between 18 and 65 years, medically well enough to undergo neuropsychological testing and MRI. Exclusion criteria included a current or history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychotic disorders, current substance or alcohol abuse or dependence, significant previous head injury, demonstrated frank dementia on the International HIV Dementia Scale, current seizure disorders of any cause, history of central nervous system infections or neoplasms, hepatitis positive status and current use or use within the last month of any psychotropic medication.

Procedure

All participants were recruited by a researcher or with the help of doctors and adherence counsellors from community healthcare facilities in and around the Cape Town area. All participants who consented were screened for eligibility and childhood trauma exposure either in person at their clinic or telephonically. Those who met initial screening criteria subsequently underwent behavioural, neuromedical, neurocognitive and neuroimaging assessments at Stellenbosch University. Participants were reimbursed for their travel costs to the University on two separate occasions.

Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, years of education and employment status were captured. A comprehensive history was obtained from, and a general physical examination conducted in, all patients. Virological markers of disease progression (CD4 lymphocyte count and viral loads) were obtained from blood samples.

Psychiatric morbidity

Current and lifetime psychiatric disorders were evaluated using the MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview-Plus (MINI-Plus).32

Depression

Participants were assessed for depressive symptomatology using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).33 The CES-D is a 20-item widely used self-report instrument designed to measure depressive symptomatology. The scale was specifically designed to measure depressive symptomatology in the general population, unlike previous depression scales that were predominantly used in clinical populations. The CES-D emphasises the affective component of depressive symptomatology, namely depressed mood. Each item comprises a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. A total score for the 20 items is obtained, with the lowest possible score being 0 and the highest possible score being 60. Higher scores are indicative of more severe depression.

Traumatic life events

Exposure to traumatic life events were assessed for using the Life Events Checklist (LEC).34 The LEC is a widely used measure of exposure to potentially traumatic events. It was developed in order to facilitate the diagnosis of PTSD. One of the LEC's unique features is that it enquires about various types of exposure to each potentially traumatic event. Therefore, the LEC elicits whether the participant experienced, witnessed or learned of the traumatic event, a feature that other traumatic event measures do not possess. Participants rate their experience of each traumatic event listed on a Likert scale. A total score is derived from the sum of experiencing and/or witnessing the event. Higher scores are indicative of the experience of more traumatic life events.

Post-traumatic stress symptomatology

Post-traumatic stress symptomatology was assessed using the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS).35 The DTS is a widely used 17-item self-report and measures symptoms of PTSD on frequency and severity scales. The items are categorised according to the criteria set out in the DSM-IV: criteria B (intrusive re-experiencing), criteria C (avoidance and numbness) and criteria D (hyperarousal). For each item, the participant rates the frequency and severity during the previous week on five-point (0–4) scales, with the lowest possible score being 0 and the highest possible score being 136. Higher scores are indicative of more PTSD symptoms.

Childhood trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form (CTQ-SF),36 a 28-item self-report inventory that provides valid screening for histories of abuse and neglect was administered. It assesses five types of maltreatment including, emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect. Each of these five subscales consists of five items with scores ranging from 5 to 25. The overall trauma score ranges from 25 to 125 with higher scores indicating higher levels of childhood trauma (score of 25–31=no trauma, 41–51=low-to-moderate, 56–68=moderate-to-severe and 73–125=severe-to-extreme).

Resilience

Resilience was assessed using the Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC).27 35 The CD-RISC is a self-report measure of resilience consisting of 25 items. The content of the scale reflects hardiness, control, commitment, personal or collective goals, change or stress viewed as a challenge/opportunity, strengthening effect of stress, past successes, recognition of limits to control, engaging the support of others, self-efficacy, optimism, action orientation, self-esteem/confidence, adaptability, tolerance of negative affect, problem-solving skills, humour in the face of stress, patience, faith and secure bonds to others. Examples of items include ‘I am able to adapt when changes occur’, ‘I have at least one close and secure relationship which helps me when I am stressed’, ‘when there are no clear solutions to my problems, sometimes fate or God can help’, ‘under pressure I stay focused and think clearly’, ‘I try to see the humorous side of things when I am faced with problems.’ The scale rates participants over the past month with a total score of the CD-RISC varying from 0 to 100. The items are scored on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting higher resilience.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, V.20.0 and Statistica, V.11.0.

Basic statistical analyses were conducted, which included descriptive statistics. Spearman correlation and multiple linear regression analyses were carried out to assess the relationship between the variables of interest.

According to Baron and Kenny37, a variable functions as a mediator when it meets the following conditions: (1) variations in the levels of the independent variable (IV) significantly account for variations in the mediator variable (MV; figure 1, path a), (2) variations in the MV significantly account for variations in the dependent variable (DV) (figure 1, path b) and (3) when paths a and b are controlled for, a previous significant relation between the IV and DV is no longer significant, with the strongest demonstration of mediation occurring when path c (figure 1) is 0. Rather than hypothesising a direct causal relationship between the IV and DV, a mediational model hypothesises that the IV influences the MV, which in turn influences the DV. In order to assess for a mediation effect, several steps were taken. First, the Sobel test for mediation was conducted to assess whether childhood trauma, traumatic life events or post-traumatic stress symptoms mediated the relationship between the DV (depression) and IV (resilience). Second, to test for mediation, one should conduct three regression equations. Separate coefficients for each equation should be estimated and tested.37 First, the MV should be regressed on the IV; second, the DV should be regressed on the IV; and third, the DV should be regressed on both the IV and the MV.37 To establish mediation, the following conditions should be met: first, the IV must affect the MV in the first equation; second, the IV must be shown to affect the DV in the second equation and third, the MV must affect the DV in the third equation. The effect of the IV on the DV should be less in the third equation than in the second. If the IV has no effect when the MV is controlled, then this is indicative of perfect mediation.37 Lastly, a PLS path analysis was performed to confirm the results of the aforementioned analyses.

Figure 1.

Mediation model.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample

Participants were predominantly black (98.9%), Xhosa (African indigenous language) speaking (93.7%) women, with a mean age of 33.6 years (range 21–50). The mean highest level of education was 9.98 years, ranging from 5 to 14 years. The majority were single (73.7%), unemployed (70.5%) and reported a combined annual household income of less than $1000 (10 000ZAR) per year (87.4%).

Clinical characteristics of the sample

The mean CD4 lymphocyte count was 438.40 cells/mm3 (range 25–1529 cells/mm3). The mean HIV viral load was 106 157.05 copies/mL, ranging from below the detectable limit to 3 200 000 copies/mL. The lower limit for detection was 40 copies/mL. The predominant HIV clade was subtype C. Forty-four (46%) of the women were on antiretroviral treatment.

Depression, PTSD and resilience scores

The mean score on the CES-D was 17.7, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 60. The mean score on the DTS was 25.5, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 116. A total of 7 women (6.5%) met criteria for current MDD and 9 (8.4%) for recurrent MDD on the MINI-Plus. Two women (1.9%) met criteria for PTSD on the MINI-Plus. The mean score on the CD-RISC was 81.7 with a minimum of 24 and a maximum of 100, respectively.

Trauma exposure

All women reported experiencing childhood trauma. The mean score on the CTQ was in the moderate-to-severe range (65.5), with a minimum of 41 and a maximum of 114. However, these women were also exposed to other discrete traumas regarded as index events for the development of PTSD. The commonest traumatic life events reported included physical assault, transport accident, fire/explosion, life-threatening illness or injury and the sudden unexpected death of a loved one. Table 1 lists all the index traumas reported in this cohort of women.

Table 1.

List of traumatic life events experienced (n=95)

| Index trauma (experienced or witnessed) | Sum (n) | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Natural disaster | 15 | 15.8 |

| Fire/explosion | 50 | 52.7 |

| Transport accident | 59 | 62.1 |

| Serious accident at work, home or while doing sports | 23 | 24.2 |

| Physical assault | 69 | 72.6 |

| Assaulted with a weapon | 52 | 54.7 |

| Sexual assault | 35 | 36.8 |

| Other unwanted/uncomfortable sexual experience | 17 | 17.9 |

| Exposure in a war zone | 8 | 8.5 |

| Captivity (kidnapped, abducted, held hostage) | 9 | 9.5 |

| A life-threatening illness or injury | 47 | 49.5 |

| Exposure to sudden/violent death (murder, suicide) | 24 | 25.3 |

| Sudden or unexpected death of someone close | 43 | 45.2 |

| Serious injury, harm or death you caused to someone else | 12 | 12.7 |

| Badly beaten by parents or guardian as a child | 23 | 24.2 |

| Badly beaten by a spouse or partner | 34 | 35.8 |

| Other life-threatening experience not listed | 8 | 8.5 |

Internal consistency

Cronbach α coefficients for all measures ranged from good to excellent: CTQ (α=0.73), LEC (α=0.78), DTS (α=0.89), CD-RISC (α=0.94), CES-D (α=0.96).

Correlation between variable of interest

Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationship between all the variables of interest. There was a significant negative correlation between depression (CES-D) and resilience (CD-RISC) scores, r=−0.28, p=<0.01. In addition, there was a significant negative correlation between post-traumatic stress symptoms (DTS) and resilience (CD-RISC), r=−0.23, p=<0.05. These correlations suggest that higher levels of resilience resulted in lower levels of self-reported depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Moreover, Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationship between the IV and MV, and the MV and DV. The IV and DV were significantly correlated with two of the presumed MVs, namely childhood trauma (CTQ) and post-traumatic stress symptoms (DTS). However, traumatic life events (LEC) were not significantly correlated with either the IV or DV, suggesting that this variable is not a mediator (table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson's correlation coefficients for all variables of interest (n=95)

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | Pearson r | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTQ | CES-D | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| CTQ | LEC | 0.12 | 0.27 |

| CTQ | DTS | −0.01 | 0.94 |

| CTQ | CDRS | 0.22 | 0.04 |

| CES-D | LEC | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| CES-D | DTS | 0.48 | <0.01 |

| CES-D | CDRS | −0.28 | <0.01 |

| LEC | DTS | 0.18 | 0.08 |

| LEC | CDRS | −0.02 | 0.84 |

| DTS | CDRS | −0.23 | 0.03 |

CDRS, Connor Davidson Resilience Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Scale; DTS, Davidson Trauma Scale; LEC, Life Events Checklist.

Multiple linear regression

Multiple linear regression with depression (CES-D score) as the outcome variable revealed a significant model of four factors: childhood trauma (β=0.330, p=0.002), other trauma exposure (β=0.181, p=0.718), post-traumatic stress symptomatology (β=0.216, p=0.000) and resilience (β=-0.236, p=0.007), of which three of the four variables were significantly associated with depression (table 3). This model explains 35% of the variance of depressive symptomatology (R2=0.35). As expected, childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms contributed to depression severity while resilience appeared to reduce it.

Table 3.

Regression model for depressive symptomatology (CES-D score; n=95)

| Variable | Df | Β | SE of β | p Value | R2 | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 4 | – | – | 0.000 | 0.347 | 0.318 |

| Childhood trauma (CTQ) | 1 | 0.330 | 0.101 | 0.002 | ||

| Other trauma (LEC) | 1 | 0.181 | 0.499 | 0.718 | ||

| Trauma symptoms (DTS) | 1 | 0.216 | 0.045 | 0.000 | ||

| Resilience (CD-RISC) | 1 | −0.236 | 0.085 | 0.007 |

CD-RISC, Connor Davidson Resilience Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Scale; DTS, Davidson Trauma Scale; LEC, Life Events Checklist.

Sobel test for mediation

To assess for mediation, the Sobel test for mediation was performed. The results showed that neither childhood trauma (CTQ; z=1.77, p=0.08) nor stressful life events (LEC; z=−0.19, p=0.84) significantly mediated the relationship between depression and resilience in this sample. However, the results demonstrated that post-traumatic stress symptomatology (DTS) was a significant mediator (z=−2.03, p=0.04).

Regression analysis

To confirm whether post-traumatic stress symptomatology (MV) in fact mediated the relationship between depression (DV) and resilience (IV), three separate regression equations were conducted following the guidelines described in the data analysis section. The first regression equation showed that the IV significantly influenced the MV, (β=−0.226, p=0.027). The second regression equation showed that the IV significantly influenced the DV, (β=−0.283, p=0.005). The third regression equation showed that the MV significantly influenced the DV, (β=0.442, p=0.000). The effect of the IV on the DV was less in the third equation than in the second equation, β=−0.183 (p=0.049) vs β=−0.283 (p=0.005). This is indicative of partial mediation. Post-traumatic stress symptoms account for some, but not all, of the relationship between depression and resilience. Partial mediation implies that there is not only a significant relationship between the mediator and the DV, but also some direct relationship between the independent and DV.

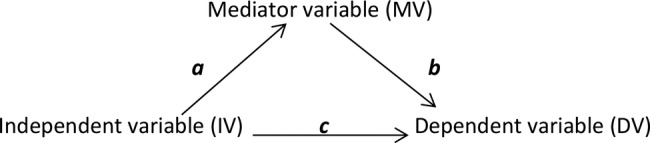

PLS path analysis

The PLS path analysis revealed a significant direct effect between depression and resilience (p<0.05). The PLS path analysis also revealed that the effects via DTS (post-traumatic stress symptoms) were also significant (p<0.05). This implies that although there is a mediating effect, there is also evidence of a direct effect. The other presumed mediators (CTQ and LEC) were not significant (p>0.05; figure 2).

Figure 2.

PLS path analysis for all variables of interest.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of 95 women infected with HIV, we found that childhood trauma, post-traumatic stress symptoms and resilience independently predicted depressive symptoms. Childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress symptomatology contributed to depression, while resilience appeared to mitigate it. The results demonstrated a significant association between depression and resilience in this cohort, with resilience acting as a protective buffer. Post-traumatic stress symptoms were found to mediate this relationship and accounted for some, but not all, of the relationship between depression and resilience.

A cut-off score of 16 or greater on the CES-D has been used to identify individuals at risk for clinical depression. Although, the mean score on the CES-D for this cohort was 17.7, this score is still relatively low. Results revealed a significant negative association between depression and resilience in this cohort of women, suggesting that resilience may be acting as a protective buffer against the development of clinically significant depression. The mean score on the CD-RISC was 81.7, suggesting high levels of resilience.

Childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms independently predicted depressive symptoms but other traumatic life events did not. Mediation analyses demonstrated that childhood trauma did not mediate the relationship between depression and resilience but post-traumatic stress symptoms did. This suggests that it is not the experience of trauma itself that contributes to depression per se, but the psychological manifestation thereof, in this case posttraumatic stress symptoms. A score of 40 and greater has been used to identify individuals with clinically significant PTSD. The mean score on the DTS in this cohort was substantially lower (25.5), once again highlighting the possible role of resilience in this cohort of women. This mediational model suggests that in this cohort, resilience influences (reduces) post-traumatic stress symptoms, which in turn influences (reduces) depressive symptoms. However, this is a partial mediation, suggesting that there is also evidence of a direct link between depression and resilience. Resilience appears to act as a protective buffer against depression, irrespective of the mediating role of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

The finding that childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress symptoms were each associated with depression is in keeping with other studies. Given that these women all reported early life stress and a number of other traumatic life events, this finding was expected. Individuals infected with HIV are at risk for psychiatric disorders such as depression and PTSD.12–16 In the South African context, PTSD is not an uncommon disorder in individuals with HIV/AIDS. In some cases, PTSD is secondary to the diagnosis of HIV/AIDS but in most cases it is seen after other traumas.15 In addition, evidence suggests that major depressive disorder is more likely to be associated with PTSD in individuals infected with HIV.15

Prior studies have examined the effects of resilience on adult psychopathology20 23 and depressive symptom severity38 in individuals with childhood abuse and/or other trauma exposure. However, this is the first study, to our knowledge, to explore the relationship between resilience and depression in a cohort of women infected with HIV with childhood trauma and to find evidence of a mediating effect of post-traumatic symptoms on this relationship. In light of the study findings, it is important to screen not only for depression but also for comorbid post-traumatic stress symptoms in individuals infected with HIV and to develop interventions that enhance resilience among these individuals.

The results of the present study should be interpreted in light of the study limitations, including potential recall bias on the retrospective rating scales, the cross-sectional study design and the potential confounding effect of comorbid psychiatric disorders. In addition, no data on non-traumatic everyday stressful life events were captured.

Future studies with longitudinal assessment of this hypothesis are needed. Understanding how resilience can be enhanced is of great importance to not only promoting coping mechanisms but also alleviating maladaptive coping and stress responses in common mental illnesses such as depression and PTSD.26

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Professor Martin Kidd for providing statistical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS made substantial contributions to the conception and design, analysis of data, revising the manuscript and providing final approval of the version to be published. GS made a substantial contribution to conception and design, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the article and providing final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work is supported by the South African Research Chair in PTSD hosted by Stellenbosch University, funded by the DST and administered by NRF, the Claude Leon Foundation and the South African Medical Research Council.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.UNAIDS Worldwide HIV & AIDS statistics. http://www.avert.org/worldstats.htm (accessed 9 Sep 2013).

- 2.Andersson N, Cockcroft A, Shea B. Gender-based violence and HIV: relevance for HIV prevention in hyperendemic countries of southern Africa. AIDS 2008;22:73–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jewkes R, Penn-Kekana L, Levin J, et al. Prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. S Afr Med J 2001;91:421–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. Sexual assault history and risks for sexually transmitted infections among women in an African township in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care 2004;16:681–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: a 30-year follow-up. Health Psychol 2008;27:149–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crepaz N, Passin WF, Herbst JH, et al. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions on HIV-positive persons’ mental health and immune functioning. Health Psychol 2008;27:4–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:721–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:725–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Ten Have T, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:789–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabkin JG, Johnson J, Lin SH, et al. Psychopathology in male and female HIV-positive and negative injecting drug users: longitudinal course over 3 years. AIDS 1997;11:507–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruess DG, Evans DL, Repetto MJ, et al. Prevalence, diagnosis, and pharmacological treatment of mood disorders in HIV disease. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:307–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myer L, Smit J, Roux LL, et al. Common Mental Disorders among HIV-Infected Individuals in South Africa: prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2008;22:147–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olley BO, Gxamza F, Seedat S, et al. Psychopathology and coping in recently diagnosed HIV. S Afr Med J 2003;93:928–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olley BO, Seedat S, Nei DG, et al. Predictors of major depression in recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2004;18:481–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olley BO, Zeier MD, Seedat S, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder among recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care 2005;17:550–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olley BO, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Persistence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa: a 6-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res 2006;61:479–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spies G, Afifi TO, Archibald SL, et al. Mental health outcomes in HIV and childhood maltreatment: a systematic review. Syst Rev 2012;1:1–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alim TN, Graves E, Mellman TA, et al. Trauma exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in an African-American primary care population. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;98:1630–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernet CZ, Stein MB. Relationship of childhood maltreatment to the onset and course of major depression in adulthood. Depress Anxiety 1999;9:169–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, et al. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse Negl 2007;31:211–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lizardi H, Klein DN, Ouimette PC, et al. Reports of the childhood home environment in early-onset dysthymia and episodic major depression. J Abnorm Psychol 1995;104:132–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie K, Jaussent I, Stewart R, et al. Association of adverse childhood environment and 5-HTTLPR Genotype with late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1281–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alim TN, Feder A, Graves RE, et al. Trauma, resilience, and recovery in a high-risk African-American population. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:1566–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feder A, Nestler EJ, Charney DS. Psychobiology and molecular genetics of resilience. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:446–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Southwick SM, Charney DS. The science of resilience: implications for the prevention and treatment of depression. Science 2012;338:79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu G, Feder A, Cohen H, et al. Understanding resilience. Front Behav Neurosci 2013;7:10–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003;18:76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enns MW, Cox BJ. Psychosocial and clinical predictors of symptom persistence vs remission in major depressive disorder. Can J Psychiatry 2005;50:769–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nanni V, Uher R, Danese A. Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:141–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson JR, Payne VM, Connor KM, et al. Trauma, resilience and saliostasis: effects of treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;20:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Min JA, Lee NB, Lee CU, et al. Low trait anxiety, high resilience, and their interaction as possible predictors for treatment response in patients with depression. J Affect Disord 2012;137:61–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:22–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radloff SF. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1977;1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, et al. Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment 2004;11:330–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med 1997;27:153–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl 2003;27:169–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wingo AP, Wrenn G, Pelletier T, et al. Moderating effects of resilience on depression in individuals with a history of childhood abuse or trauma exposure. J Affect Disord 2010;126:411–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.