Abstract

Objectives

For characterisation of mineral bone disease in chronic kidney disease (CKD), laboratory surrogates have been suggested. This observational should investigate the association of total and skeletal alkaline phosphatase (AP) with mortality of patients undergoing maintenance renal replacement therapy.

Setting

Three renal outpatient centers in eastern-central Germany (secondary and tertiary care).

Participants

Complete survival and laboratory datasets were available in 407 of 493 patients. Age and gender distribution was equivalent to a general population with end-stage CKD (CKD5D). Patients were included between 2008 and 2010 if at least 2 weeks of maintenance treatment were documented.

Primary outcome measures

Mortality was estimated by setting the end of dialysis date as event date. Events other than death (change to another centre, life-sustaining renal function or transplantation) were censored.

Results

The OR to die within follow-up for patients in the higher of two total AP strata was 2.70 (95% CI 1.76 to 4.15). In univariate Kaplan-Meier analysis, total AP had a strong association with all-cause mortality (LogRank=24.1, p<0.001). Mean total AP and individual lowest skeletal AP, but not mean skeletal AP entered step-wise Cox models for survival from dialysis start (χ2=22.4; p<0.001) after adjusting for age, Kt/V, diabetes and vintage. Mean values of skeletal, total AP and parathyroid hormone were 14.8±8.9 µg/L, 91.9±55.3 U/L and 188±164 ng/L, respectively. Skeletal and total AP were highly correlated (R=0.86; p<0.001).

Conclusions

This unselected CKD5D population exhibited a clinical significant association of total AP with crude mortality and a stronger death risk association of total AP and individual lowest skeletal AP with crude mortality.

Keywords: Statistics & Research Methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Observational and non-interventional, but non-selected comprehensive cohort study on the association of routine bone markers with crude mortality in patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease.

This study included laboratory surrogates that are commonly used in routine praxis and interdependent correlations analyses of such markers.

Use of longitudinal averages of such markers instead of one-time cross-sectional measurement.

Smaller sample size compared with other observations in the field (but clearly significant results even with those numbers).

There was no regard to vitamin D metabolism or inflammation markers in this study.

Introduction

Backgrounds

Surrogates of bone metabolism have been applied to patients with end-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD5D) to characterise their ‘bone status’ with regard to suspected relationship between mineral bone disease of patients with CKD (CKD-MBD) and mortality. Albeit some more elaborated compounds such as osteocalcin, cross-links and FGF-231 have been investigated recently, serum Ca and PO4, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and AP including its compartmental skeletal subclass have presumably the widest distribution in clinical routine. AP is an early differentiation marker of osteoblasts and osteoblastic activity.2 Three of four AP-encoding genes are expressed in a tissue-specific manner (placental, embryonic and intestinal AP isoenzymes).3 Expression of the fourth AP gene is non-specific to a single tissue and is especially abundant in bone, liver and kidney (tissue non-specific AP).

Studies analysing the association of skeletal and total AP with mortality, especially in the dialysis population have been conducted even in large scale but not with comprehensive characterisation of long-term fluctuation and of interdependent surrogates. Some studies suggest mainly skeletal AP, which reflects AP derived exclusively from bone, to be a predictor of mortality in this population4 5 without making comparisons with total AP. In an analysis of a Dutch subcohort from the NECOSAD study, the effects of skeletal AP were more accentuated compared with total AP.6 The group around Shimizu et al7 investigated the association of total AP with the risk of stroke in Japan in a prospective cohort with 16 years of follow-up and demonstrated a U-shaped association between total AP level and stroke incidence with the lowest total AP levels associating with a higher risk of stroke. A Korean group8 showed increased serum levels of total AP to be an independent predictor of all-cause and vascular death after stroke, but in a rather linear relationship without U-shaped or J-shaped curves. An almost linear relationship in the association of total AP values with relative risk of death was shown in an analysis of more than 58 000 patients with haemodialysis (HD) in the USA by Kalantar-Zadeh et al with no regard to skeletal AP.9

Regidor et al10 studied a cohort of almost 74 000 patients with HD in the USA and showed an incremental association of total AP with increased death risk over 3 years, even after adjustment for surrogates of nutrition, inflammation, minerals, serum PTH and liver enzymes. Beddhu et al11 could also show the association of higher serum total AP with all-cause mortality in a longitudinal analysis of the HEMO Study database. Similar conclusions for HD populations were found in the studies of Blayney et al12 and Yamashita et al.13 Shantouf et al 14 showed the association of serum AP and increased coronary artery calcification in patients with HD.

Higher serum total AP levels were also shown to be associated with increased mortality and end-stage renal disease in non-dialysis patients with CKD 3–415 and in patients with normal kidney function.16

Objectives

From an epidemiological point of view, non-selected coverage of a population is more helpful for analysis of a variables impact on outcome than analysis of a spot-check sample or subgroup. The prespecified aim of the present study was therefore to analyse the differential association of time-averaged bone markers with survival of patients with CKD5D including their interdependency and confounding by other clinical parameters. With regard to the available data distribution, secondary analyses were conducted to explore the relationship of single values of marker distribution with mortality.

Methods

Study setting and participants

The outpatient units provided maintenance renal replacement therapy for 493 patients annually. Patients from three renal units in eastern-central Germany undergoing maintenance therapy were included in this analysis. The laboratory marker dataset of the present study was determined in 2008, 407 prevalent patients were recruited on a cross-sectional basis from 2008 to 2010, and the mortality registration was conducted from 2008 to 2013. Patients included were treated for at least 2 weeks within the maintenance programmes and no patients necessitating temporary renal replacement were included. Treatment (HD and peritoneal dialysis, PD) was conducted following international guidelines in terms of dialysis dosage and techniques,17 mineral bone disease and other clinical management. Patients were informed about laboratory tests and results, but no consent was sought because no intervention was performed.

Study design

After prespecified cross-sectional acquisition of laboratory data, anthropometrical, clinical and mortality data were registered during clinical routine in a 5-year follow-up (non-selected observational longitudinal registry).

Variables and data sources

Trained nurses in the dialysis units collected blood specimen between 2008 and 2010 in all patients for routine biochemistry after the long dialysis interval on a monthly (Ca, PO4) or three-monthly (AP, PTH) routine basis. Analyses were performed in associated laboratories by industry-standard operating procedures (for PTH: sample harvest at any daytime pertaining to the time of dialysis shift). Patients with overt gallbladder or bile duct disease were not included to avoid bias by analysing AP level increases based on cholestasis. For computation of averages of markers, at least three laboratory investigation time points within the 3 years of laboratory testing were used. As a starting time for survival after laboratory test, the date of the first investigation was set.

Clinical courses were followed by review of paper-based and computer-based records and merged to an SPSS database after identifying information was removed. Causes of death were categorised as follows: (1) cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events, that is, myocardial infarction, ischaemic congestive heart failure, peripheral artery disease, stroke, sudden death, fatal arrhythmias and pulmonary embolism; (2) sepsis and infectious events, pneumonia; (3) malignant diseases; (4) other death causes and (5) unknown causes.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics of patient data with pseudonym ID numbers were produced using standard procedures with the SPSS V.13.0 programme package. Survival analysis was conducted by multivariate (Cox) and univariate procedures (Kaplan-Meier) and dichotomised for bimodal population strata depending on total AP values. Survival analyses were performed using death as endpoint. Start time was the first dialysis date (survival plots) or the time of median laboratory analysis; end time was the last dialysis date. All survival analyses were conducted for both time-periods. All events leading to the loss of follow-up other than the end-points (transplantation, change to another unit, change to life-sustaining renal function and end of observation in May 2013) were censored and indicated by crosses within the survival plot lines. Survival plots were truncated at 5 or 10 years, respectively. In multivariate Cox regression analyses, covariates were first analysed using a non-conditional overall model. Second, covariates with primary significant association with mortality (p<0.05) and further parameters of interest (Ca, PO4, PTH) were subjected to forward conditional stepwise analyses. Covariates remaining in that second equation were considered significant. A second set of Cox stepwise regressions were performed without including total AP to retrieve the independent impact of skeletal AP. Association measures in Cox regressions are given as Wald coefficients resembling the strength of association, p resembling the significance and exp. (HRs including 95% CIs) resembling the quantitative risk increase along with an increase of one numerical unit of a covariate.

Results

Between 2008 and 2010, a total of 719 patients including patients with acute renal failure and hospitalised patients were treated with HD or PD in three participating dialysis units. Biochemistry datasets were retrieved for 407 patients. Characterisation of these patients after dichotomisation by total AP level averages into two equal-size strata (divided at 77.5 U/L) is shown in table 1. Between AP strata, no significant population differences were observed except from different average and variability values of total and skeletal AP values and a borderline difference concerning the presence of diabetes.

Table 1.

Patient characterisation in two equal strata according to the median of total AP value

| Patients within lower AP stratum±SD N=203 |

Patients within higher AP stratum±SD N=204 |

All patients±SD N=407 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.3±15.3 | 66.9±14.1 | 66.1±14.7 | 0.286 |

| Vintage (dialysis time before laboratory test; years) | 2.99±3.53 | 2.83±3.41 | 2.91±3.46 | 0.721 |

| Median | 1.64 | 1.38 | 1.5 | 0.63 |

| Proportion of males (%) | 59.1 | 55.9 | 57.5 | 0.548 |

| Proportion of patients with diabetes (%) | 42.9 | 57.4 | 50.1 | 0.042 |

| Proportion of patients on PD (%) | 3.5 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 0.639 |

| Weekly Kt/V (in patients with PD) | 3.16±1.03 | 2.13±1.30 | 2.48±1.28 | 0.121 |

| Single pool Kt/V (in patients with HD) | 1.55±0.527 | 1.52±0.473 | 1.54±0.501 | 0.512 |

| Proportion of patients on Ca-free PO4 binders (%) | 12.8 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 0.947 |

| Proportion of patients on cinacalcet (%) | 16.7 | 15.7 | 16.2 | 0.627 |

| Mean total AP (U/L) | 62.1±10.5 | 121±65.1 | 91.9±55.3 | <0.001 |

| Individual number of AP tests (n) | 6.98±3.02 | 5.76±3.23 | 6.37±3.18 | <0.001 |

| Individual range of AP levels (U/L) | 25.9±24.1 | 61±76.4 | 43.4±59.3 | <0.001 |

| Individual lowest AP level (U/L) | 53.3±10.7± | 97.6±55.3 | 55.6±45.7 | <0.001 |

| Mean skeletal AP (µg/L) | 10.3±2.68 | 19.2±10.6 | 14.8±8.94 | <0.001 |

| Median skeletal AP (µg/L) | 9.9 | 16.7 | 14.8 | <0.001 |

| Individual number of sAP tests (n) | 7.53±3.53 | 6.09±3.59 | 6.81±3.63 | <0.001 |

| Individual range of sAP levels (U/L) | 6.08±5.09 | 12.7±14.7 | 9.4±11.5 | <0.001 |

| Individual lowest sAP level (U/L) | 7.89±2.17 | 14.0±9.2 | 10.9±7.34 | <0.001 |

| Mean PTH (ng/L) | 175±147 | 201±178 | 188±164 | 0.103 |

| Median | 143 | 171 | 188 | 0.103 |

| Mean Ca (mmol/L) | 2.21±0.155 | 2.19±0.181 | 2.21±0.169 | 0.295 |

| Mean PO4 (mmol/L) | 1.61±0.382 | 1.60±0.403 | 1.61±0.392 | 0.724 |

PD, peritoneal dialysis; PTH, parathyroid hormone; sAP, skeletal alkaline phosphatase; SD, standard deviation.

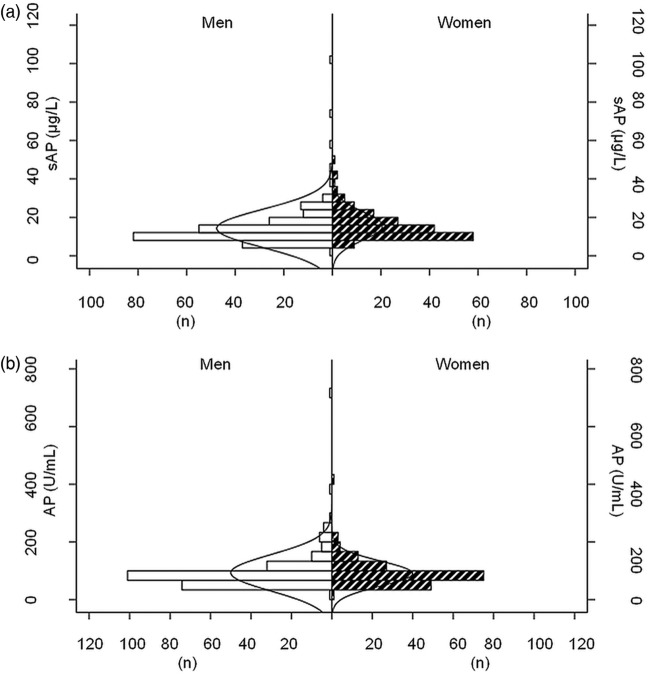

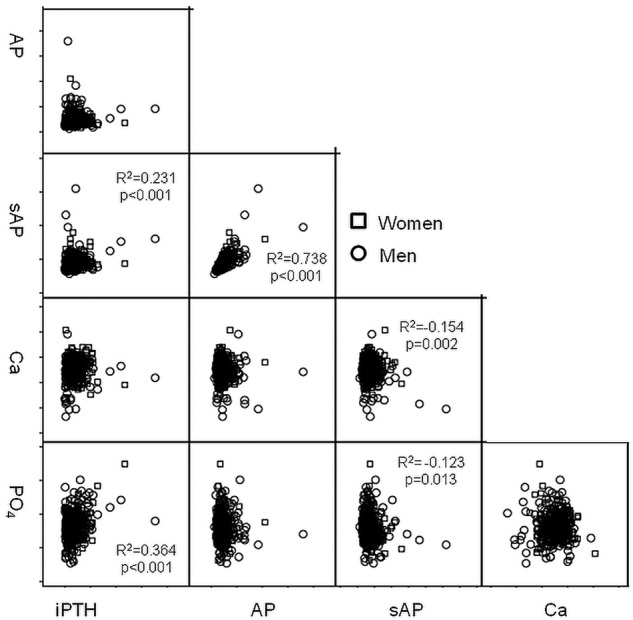

Distribution of total and skeletal AP levels is given in figure 1A,B. The histogram distribution curves were not different between men and women. The correlation of markers with each other is given in figure 2. Significant correlations were found between PTH and PO4, PTH and skeletal AP, but not between total AP and PO4 serum levels.

Figure 1.

Histogram of sAP (A) and AP value (B) distribution in men (left) and women (right).

Figure 2.

Correlation of intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), total and skeletal AP, Ca and PO4 with each other.

Mortality analyses showed significant association of total AP with all-cause mortality and subgroups of death reasons (table 2). For non-censored patients in the higher AP stratum the global OR to die within observation compared with patients in the lower AP stratum was 2.70 (95% CI 1.76 to 4.15).

Table 2.

Causes of deaths by total AP concentration stratum

| Cause of death | Lower AP stratum N=203 |

Higher AP stratum N=204 |

All patients N=407 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular (n (%)) | 35 (17.2) | 62 (30.4) | 97 (23.8) | <0.0001 |

| Infectious (n (%)) | 18 (8.9) | 30 (14.7) | 48 (11.8) | 0.003 |

| Malignant (n (%)) | 9 (4.4) | 16 (7.8) | 25 (6.1) | 0.02 |

| Other (n (%)) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (2) | 5 (1.2) | n.s. |

| Unknown (n (%)) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | n.s |

| All deaths | 65 (32) | 113 (55.4) | 178 (43.7) | <0.0001 |

n.s., not significant.

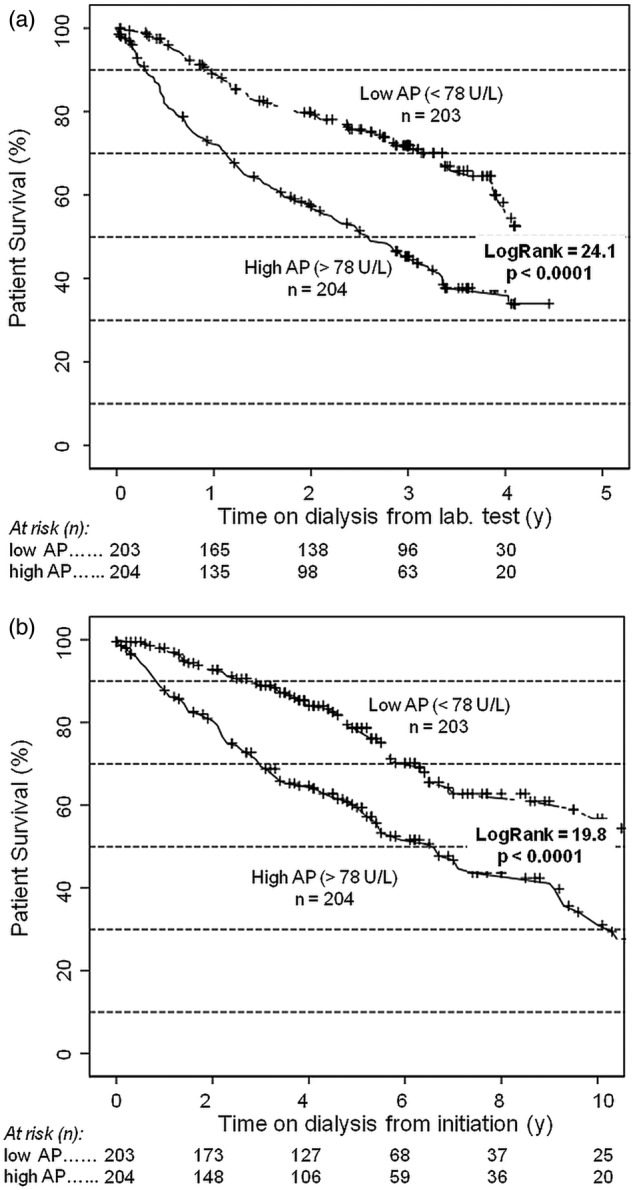

Kaplan-Meier studies yielded strong and significant patterns of associations between total AP strata and survival both from median and first laboratory test (Logrank 19.8 and 27.5, respectively, p<0.0001) and from dialysis start (figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

Survival after laboratory test (A) and dialysis initiation (B; Kaplan-Meier) by total AP strata.

Concerning skeletal AP, lower individual minimum sAP levels were associated with better survival both from dialysis start (Logrank 17.7, p>0.001) and from first laboratory test (Logrank 29.9, p<0.001) in secondary analyses. Patients within the low skeletal AP stratum had better survival after laboratory tests (Log Rank=8.90, p=0.003, plot not shown) but not after dialysis initiation.

In multivariate global Cox regression all parameters given in table 1 were considered. Age, vintage, presence of diabetes, Kt/V mean total and skeletal AP and lowest individual AP yielded significant mortality associations in these primary analyses.

For forward conditional regressions age, vintage, presence of diabetes, Kt/V, mean total and skeletal AP, Ca, PO4 and PTH and lowest individual sAP were used. Presence of diabetes, age, vintage, total AP and lowest individual sAP had independent significant associations with all-cause mortality (table 3). There was a positive association of the individual low extremes of skeletal AP and mortality: the higher the lowest ever measured sAP level, the higher the risk of mortality.

Table 3.

Significant association of different covariates with all-cause mortality (forward conditional Cox regression)

| From dialysis start |

From first laboratory |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald | p Value | HR (95% CI)* | Wald | p Value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age | 31.4 | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | 32.7 | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.03 to 1.063) |

| Vintage | 95.6 | <0.001 | 0.509 (0.449 to 0.577) | 110 | <0.001 | 0.520 (0.458 to 0.590) |

| Diabetes | 15.4 | <0.001 | 2.124 (1.46 to 3.09) | 9.80 | 0.008 | 1.71 (1.22 to 2.40) |

| Kt/V | 4.83 | 0.031 | 0.619 (0.403 to 0.949) | 4.432 | 0.035 | 0.647 (0.432 to 0.654) |

| PTH | 2.55 | 0.601 | 0.834 | 0.923 | ||

| PO4 | 1.52 | 0.530 | 0.097 | 0.754 | ||

| Ca | 0.82 | 0.150 | 0.000 | 0.883 | ||

| Total AP | 37.7 | <0.001 | 1.01 (1 to 1.01) | 40.75 | 0.043 | 1 (1 to 1.01) |

| sAP | 2.10 | 0.089 | 1.74 | 0.182 | ||

| Individual minimum sAP | 20.4 | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.21) | 23.5 | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.24) |

| sAP calculations after AP exclusion | ||||||

| sAP | 6.62 | 0.021 | 0.937 (0.891 to 0.985) | 7.94 | 0.005 | 0.923 (0.876 to 0.977) |

| Individual minimum sAP | 20.4 | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.08 to 1.21) | 23.5 | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.10 to 1.24) |

*Given as relative risk for every numerical unit of covariate to increase risk of mortality (exp. (B)) or binary relative risk for the categorical covariate presence of diabetes.

PTH, parathyroid hormone.

The association of mean sAP disappeared, when AP was not included into the Cox models. These patterns of associations did not change, when subgroups of death causes (cerebrocardiovascular vs infectious vs malignant vs other) were used as endpoints (data not shown). In forward conditional mode, with stepwise model building after adjusting for vintage, age, Kt/V and presence of diabetes, total AP yielded a residual χ2 of 22.4 (overall survival; p<0.001) or a residual χ2 of 23.9 (survival after laboratory test p<0.001), respectively. No J-shaped or U-shaped mortality association was found when looking at association of mean low or high AP and sAP values.

Discussion

This retrospective investigation from three independent renal units showed a robust association between total AP levels, lowest individual skeletal AP and all-cause mortality. For the first time, such association has been found on the basis of time series of markers values in a non-selected dialysis population. The weaker association of mortality with mean skeletal AP might be explained by the multicollinearity between total and skeletal AP. The association of lowest individual sAP values with survival was found in a secondary analysis. Our finding is remarkable for at least two reasons. First, until now, among available ‘bone markers’ skeletal AP was seen as a more particular attribute of increased bone turnover compared with overall AP. Our data indicate that (1) skeletal AP and total AP are highly correlated and (2) that the weaker associations of mean skeletal AP disappear if total AP was included into multivariate comparisons although a very low individual sAP may have a positive prediction for better survival. No further meaningful subgroups could be generated by looking at interdependent correlations of the other markers (Ca, PO4, PTH). Therefore, following our data, to appreciate the meaning of bone markers with regard to the prognosis of CKD5D patients, not only single values, but time-trends, mean values and extremes must be considered. Total AP provided good association concerning mean long-term values, but low individual sAP extremes characterise patients at low risk as well.

Second, our dataset does not provide evidence for impact of known surrogates of CKD-MBD like phosphate or parathyroid hormone level while it yields strong evidence for an impact of AP and sAP under conditions of patients being treated following recent guidelines. This issue might be surprising, because known associations, at least for phosphate18 could not be reproduced. The study of Block et al showed a two-fold elevated risk of death in patients with PO4 levels above 9 mg/dL (2.9 mmol/L). These high levels were not observed in our (smaller) population, presumably due to a more intensive pharmacological and non-pharmacological management. We would however encourage inclusion of phosphate levels under treatment into future studies to differentiate impacts of ‘new’ and ‘old’ risk factors.

Our study used routine, time-scheduled longitudinal laboratory investigations during a 3-year period. As start times for survival analyses, both dialyses start as well as first or median dates of laboratory tests were used. In all time periods, the associations with mortality either with or without adjusting for vintage (ie, dialysis time before laboratory tests) were robust. Variance of markers over time was between 30% and 80% and did not contribute to associations directly with the exception of lowest individual sAP being associated with better survival. The latter was evident for sAP, but not for total AP and illustrates the somewhat arbitrary meaning of retrospective analyses of time-series values. Moreover, because total and skeletal AP were highly correlated it is difficult even in multivariate models to discriminate the predictive value of markers from each other. While taking a clinical approach, the lowest ever value of a certain marker cannot be defined during treatment. Therefore, paying attention to time courses might be a helpful approach to draw conclusion from AP estimations.

Even if the analysis time is after dialysis initiation, such patients with higher total AP levels during follow-up seem to be exposed to higher risk of death. Our results were found in a non-selected population without regard to therapy of CKD-MBD, ‘bone status’ or other selection bias. The results were clearly significant even in a study population which is smaller compared with other studies. This latter issue underlines the clinical need to understand the phenomenon and to consider clinical measures in every single patient with high AP levels. While no discrete signal threshold out of the total AP distribution in our cohort could be retrieved, the number needed to harm was 4.4 for those patients who had a total AP higher than 77 U/L in the average of three measuring time-points.

Clearly, our findings require further analysis. Quantitative analyses of the impact of total AP levels have been conducted in independent populations. Our data must be reproduced in a larger cohort including all covariates of CKD-MBD which is different from studies investigating subsets of markers. Significant data and pathophysiological considerations have incriminated ‘bone markers’ to be associated with mortality. One of the potential mechanisms of action of AP influencing mortality in CKD patients is supposed to be via its degrading (hydrolysing) effects on inorganic pyrophosphate. Such mechanism could be thought to be independent from bone turnover as being characterised by high AP and/or PTH because in our dataset no increased mortality along with low AP or PTH appeared. Pyrophosphate is a potent inhibitor of vascular calcification.19–21 This phenomenon might be stimulated by vascular injury and AP release following smooth muscle cell osteoblastic transformation by tumour necrosis factor α.22 Growing data is available linking high AP to the development of uraemic vascular calcification.20 In line with this, clinical studies have found serum AP to be associated with coronary artery calcification, cardiovascular-related mortality and all-cause mortality in patients with CKD and on HD. Total AP might have an independent pathophysiological impact on calcification apart from the turnover marker sAP, which in our data, yielded an association between lowest individual sAP and better survival. It is not clear, if these associations are of causal or by-standing nature. Interventional studies with an attempt to decrease AP serum levels along with inflammation and calcification surrogates and subsequent analysis of outcome should be implemented following the associations which others and we have found in the recent study.

In summary, we presented a non-selected study in 407 European CKD5D individuals showing a strong and robust association of average total AP and individual lowest sAP serum levels with all-cause mortality. The weaker association of skeletal AP levels might be explained by a strong AP—sAP correlation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JB was involved in design, data retrieval, data analysis and manuscript writing. RW took part in data analysis and manuscript writing. K-HQ contributed in design and data retrieval. PJ, RF and MG were involved in design, data analysis and manuscript writing.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MG and JB report having received speaker honoraria from Amgen and Abbvie. These speaker fees are not related to the presented study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Raw data can be accessed via email to JB.

References

- 1.Lewis R. Mineral and bone disorders in chronic kidney disease: new insights into mechanism and management. Ann Clin Biochem 2012;49(Pt 5):432–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stepan JJ, Lachmanova J, Strakova M, et al. Serum osteocalcin, bone alkaline phosphatase isoenzyme and plasma tartrate resistant acid phosphatase in patients on chronic maintenance hemodialysis. Bone Miner 1987;3:177–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millán JL. Mammalian alkaline phosphatase: from biology to applications in medicine and biotechnology. Weinheim: Wiley, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi I, Shidara K, Okuno S, et al. Higher serum bone alkaline phosphatase as a predictor of mortality in male hemodialysis patients. Life Sci 2012;90:212–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Herberth J, Browning SR, et al. Bone markers predict cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:1850–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drechsler C, Verduijn M, Pilz S, et al. Bone alkaline phosphatase and mortality in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1752–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu Y, Imano H, Ohira T, et al. Alkaline phosphatase and risk of stroke among Japanese: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;22:1046–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryu WS, Lee SH, Kim CK, et al. Increased serum alkaline phosphatase as a predictor of long-term mortality after stroke. Neurology 2010;75:1995–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kovesdy CP, Ureche V, Lu JL, et al. Outcome predictability of serum alkaline phosphatase in men with pre-dialysis CKD. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:3003–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, Mehrotra R, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase predicts mortality among maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;19:2193–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beddhu S, Ma X, Baird B, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase and mortality in African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1805–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blayney MJ, Pisoni RL, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. High alkaline phosphatase levels in hemodialysis patients are associated with higher risk of hospitalization and death. Kidney Int 2008;74: 655–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita T, Shizuku J, Ohba T, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels and mortality of chronic hemodialysis patients. Int J Clin Med 2011;2:388–93 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shantouf R, Kovesdy CP, Kim Y, et al. Association of serum alkaline phosphatase with coronary artery calcification in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1106–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taliercio JJ, Schold JD, Simon JF, et al. Prognostic importance of serum alkaline phosphatase in CKD stages 3–4 in a clinical population. Am J Kidney Dis 2013;62:703. –10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abramowitz M, Muntner P, Coco M, et al. Serum alkaline phosphatase and phosphate and risk of mortality and hospitalization. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:1064–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Kidney Foundation NKF-DOQI clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30(3 Suppl 2):S15–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM, et al. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004;15:2208–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Towler DA. Inorganic pyrophosphate: a paracrine regulator of vascular calcification and smooth muscle phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:651–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lomashvili KA, Garg P, Narisawa S, et al. Upregulation of alkaline phosphatase and pyrophosphate hydrolysis: potential mechanism for uremic vascular calcification. Kidney Int 2008;73: 1024–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narisawa S, Harmey D, Yadav MC, et al. Novel inhibitors of alkaline phosphatase suppress vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:1700–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HL, Woo KM, Ryoo HM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases alkaline phosphatase expression in vascular smooth muscle cells via MSX2 induction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;391:1087–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.