Abstract

Background

Sustained release of local anesthetics is frequently associated with myotoxicity. We investigate the role of particulate delivery systems and of the pattern of drug release in causing myotoxicity.

Methods

Rats were given sciatic nerve blocks with bupivacaine solutions, two types of bupivacaine-containing microparticles (polymeric microspheres and lipid-protein-sugar particles), or blank particles with or without bupivacaine in the carrier fluid. Myotoxicity was scored in histological sections of the injection sites. Bupivacaine release kinetics from the particles was measured. Myotoxicity of a range of bupivacaine concentrations from exposures up to 3 weeks was assessed in C2C12 myoblasts, with or without microparticles.

Results

Both types of bupivacaine-loaded microparticles, but not blank particles, were associated with myotoxicity. While 0.5% bupivacaine solution caused little myotoxicity, a concentration of bupivacaine that mimicked the amount of bupivacaine released initially from particles caused myotoxicity. Local anesthetics showed both concentration and time-dependent myotoxicity in C2C12s. Importantly, even very low concentrations, that were nontoxic over brief exposures, became highly toxic after days or weeks of exposure. The presence of particles did not increase bupivacaine myotoxicity in vitro, but did in vivo. Findings applied to both particle types.

Conclusions

While the release vehicles themselves were not myotoxic, both burst and extended release of bupivacaine were. A possible implication of the latter finding is that myotoxicity is an inevitable concomitant of sustained release of local anesthetics. Particles, and perhaps other vehicles, may enhance local toxicity through indirect mechanisms.

Introduction

A wide variety of controlled release formulations have been developed, including surgically implantable pellets 1, liposomes 2–6, lipospheres 7, cross-linkable hyaluronic acid matrices 8, lipid-protein-sugar particles 9 and polymeric microspheres 10–17. These formulations prolonged the duration of local anesthesia to varying degrees, ranging from prolongation by a number of hours to nerve blockade lasting several weeks. We have found that muscle injury is a concomitant of a wide range of formulation types 8,16,17. Myotoxicity is a well-recognized side-effect of local anesthetic administration, perhaps particularly of extended exposure, whether from controlled release methodologies or from catheter-related methods 18. Occasionally, the consequences can be clinically significant 19. Polymeric microspheres themselves produce an acute local inflammatory response (neutrophils and macrophages), which is followed by a chronic response (macrophages and lymphocytes) after about 7 days 20. Hydrogels can also induce an inflammatory response 8. However, neither carrier induces the characteristic finding of local anesthetic myotoxicity 8. In fact, the muscle injury from controlled release local anesthetic formulations appears to be largely due to the encapsulated drug, rather than the vehicle itself 8,17. It is not clear whether the vehicles contribute indirectly to the quite severe muscle injury that can develop.

Here we examine the relative contributions of drug and vehicle in the development of muscle injury, focusing on two microparticulate formulations with very different compositions and morphologies – polymeric (poly [lactic-co-glycolic]) microspheres and lipid-protein-sugar particles. We investigate the potential impacts of both burst release and continuous release on the development and maintenance of myotoxicity from controlled release devices.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care Committee

Animals were cared for in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA), and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the U. S. National Research Council.

Chemicals

1, 2- Dipalmitoyl-sn- glycero-3-phosphocholine was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Bupivacaine hydrochloride, bovine serum albumin, and α-Lactose Monohydrate were from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA; M.W. 90 kDa, G:L=65:35) was obtained from Medisorb (Alkermes; Cambridge MA).

Microparticle preparation

PLGA microparticles were prepared as described 9. In brief, PLGA dissolved in methylene chloride was homogenized at 3000 rpm (Silverson L4RT-A, Longmeadow, MA) for 1 minute in 1% poly(vinylalcohol) (M.W. 25 kDa, Polysciences, Inc, Warrington, PA) containing 100 mM Tris pH 8.5. The methylene chloride was removed by rotary evaporation. Particles of the desired size range were separated by wet sieving, then lyophilized to dryness. In particles containing drug, bupivacaine free base was substituted for 50% of the polymeric mass dissolved in methylene chloride.

Blank 1, 2- dipalmitoyl-sn- glycero-3-phosphocholine -albumin-lactose (DAL) particles were prepared as described 9 using a Büchi 190 Mini Spray Dryer (Büchi Co, Switzerland). In brief, 1, 2- dipalmitoyl-sn- glycero-3-phosphocholine dissolved in 100% ethanol was mixed with an aqueous solution of bovine serum albumin and α-Lactose Monohydrate, such that the final solute composition was 60% 1, 2- dipalmitoyl-sn- glycero-3-phosphocholine, 20% albumin, and 20% lactose in 70:30 (v/v) ethanol:water. This solution was spray dried under the following conditions: inlet temperature 110–115°C, air flow 600 L/h, flow rate 12 mL/min, and aspirator pressure −20 mbar. The resulting outlet temperature was between 50 and 55°C. In particles containing drug, bupivacaine free base was added to the ethanolic solution, to an amount that equaled 10% of the total solute mass. The total mass of the other three solutes was reduced by an equal amount.

Particle size was determined with a Coulter Multisizer (Coulter Electronics Ltd., Luton, U.K.).

In vitro release of bupivacaine from microparticles

Fifty mg of DAP particles or PLGA microspheres were suspended in 1 ml phosphate buffered saline pH 7.4 at 37°C and inserted into the lumen of a Spectra/Por 1.1 Biotech Dispodialyzer (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguz, CA) with an 8,000 MW cutoff. The dialysis bag was placed into a test tube with 12 ml phosphate buffered saline and incubated at 37°C on a tilt-table (Ames Aliquot Mixer, Miles). At predetermined intervals, the dialysis bag was transferred to a test tube with fresh phosphate buffered saline. The bupivacaine concentration in the dialysate was quantitated by measuring absorbance at 272 nm and referring to a standard curve. Observation of the entire spectrum, and performance of a protein assay (BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit, Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) confirmed the absence of albumin from the samples that were measured. Infinite sink conditions were maintained during the release experiments as evidenced by low concentrations of released drug (< 0.17 mg/ml).

Animal Care and Sciatic Blockade Technique

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) weighing 310 – 420 g were housed in groups, in a 6 AM – 6 PM light-dark cycle. Under brief isoflurane-oxygen anesthesia, a 23G needle was introduced postero-medial to the greater trochanter, the needle was withdrawn approximately 1 mm and 0.3 ml of drug-containing solution was injected.

Assessment of Nerve Blockade

Thermal nociception was assessed by a modified hotplate test 1,21. Hind paws were exposed in sequence (left then right) to a 56°C hot plate (Model 39D Hot Plate Analgesia Meter, IITC Inc., Woodland Hills, CA). The time (latency) until paw withdrawal was measured by a stopwatch. (Thermal latency in the un-injected leg was a control for systemic effects of the injected agents.) If the animal did not remove its paw from the hot plate within 12 seconds, it was removed by the experimenter to avoid injury to the animal or the development of hyperalgesia. The experimenter was blinded as to what treatment specific rats were receiving.

The duration of thermal nociceptive block was calculated as the time required for thermal latency to return to a value of 7 seconds from a higher value. Seven seconds is the midpoint between a baseline thermal latency of approximately 2 seconds in adult rats, and a maximal latency of 12 seconds.

Tissue harvesting and histology

The sciatic nerve and adjacent tissues were harvested after euthanasia with carbon dioxide and processed to produce hematoxylin/eosin stained slides 17. In all analyses, the pathologist (Robert Padera) was not aware of the nature of the samples prior to examination. Samples were scored for myotoxicity (0–6) 22. The myotoxicity score reflected two separate but related processes that are hallmarks of local anesthetic myotoxicity: nuclear internalization, and regeneration. The former is characterized by normal size and cytoplasm chromicity, but with nuclei located away from their normal location at the periphery of the cell. In the latter case, cells are shrunken, with more basophilic cytoplasm. Score of 0 = normal, 1 = perifascicular internalization, 2 = deep internalization (> 5 cell layers), 3 = perifascicular regeneration, 4 = deep regeneration, 5 = hemifascicular regeneration, 6 = holofascicular regeneration.

Cell Culture

C2C12 mouse myoblasts (American Type Culture Collection CRL-1772, Manassas, VA) were cultured to proliferate in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 20%fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% Penicillin Streptomycin. All cell culture supplies were purchased from Invitrogen unless otherwise noted. Cells were then plated in 24 well tissue culture plates with 50,000 cells/ml/well in DMEM supplemented with 2% Horse Serum and 1% Penn Strep, and left to differentiate into myotubules for 10–14 days. During differentiation media were exchanged every 2 to 3 days.

Bupivacaine hydrochloride was added to DMEM (with 2% HS and 1% Penn Strep) at a concentration of 0.125% w/v. The medium was then filtered through a 0.22 μm cellulose acetate membrane then serially diluted to prepare the remaining concentrations. Particles were irradiated with ultraviolet light for 2 hours prior to suspension in media and serial dilution. The medium had a neutral pH at the outset; subsequently pH was monitored by use of a pH-sensitive dye in the medium.

For time points longer than 4days, the drug medium was exchanged every 2 to 3 days. Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 with the remainder being room air.

Assessing viability

To quantitatively assess cell viability after adding drug- or particle- containing media, a colormetric assay (MTT kit, Promega G4100 Madison, WI; MTT is the common abbreviation for 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) was performed at selected time points. The yellow tetrazolium salt is metabolized in live cells to form insoluble purple formazan crystals. The purple crystals are solubilized by the addition of a detergent. The color can then be quantified by spectrophotometric means. At each time point 150 μl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide was added and then cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 hours before 1 ml solubilization solution (detergent) was added. The absorbance was read at 570nm using the SpectraMax 384 Plus fluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) after being incubated in the dark overnight. Cells were also monitored visually to confirm the results of the assay. Each plate had wells that contained medium without cells or other additives whose absorbance was subtracted from the rest of the plate as background. Each plate also had wells that contained medium and cells but no additives; all experimental groups were normalized to those wells.

Statistical Analysis

Neurobehavioral data are presented as medians, with 25th and 75th percentiles in parentheses, as they were not normally distributed. They were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U-test, or a Wilcoxon signed ranks test when comparing sensory and motor tests in the same animals. Results of cell survival assays were described with parametric measures and tests (means, standard deviation, t-test, ANOVA). A p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Multiple comparisons were done in a planned manner (i.e. comparisons were selected individually), and the p-value required for statistical significance (α) was determined by dividing 0.05 by the number of comparisons. Thus, for mytotoxicity scores (10 comparisons), α = 0.05/10 = 0.005, so p < 0.005 was required for statistical significance; for durations of block and cell culture data there was only one comparison so the α remained 0.05. For ease of understanding, the α for each comparison is provided with each result. All p-values are two-tailed. Statistical analyses were done with SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Production and characterization of microparticles

The DAL particles were produced as a fine white powder, with a median volume-weighted diameter of 4 to 5 μm. The PLGA particles were also a white powder, with a median volume-weighted diameter of approximately 60 μm. These values are in agreement with out previous reports for similar particles 9.

Myotoxicity from microparticles containing bupivacaine

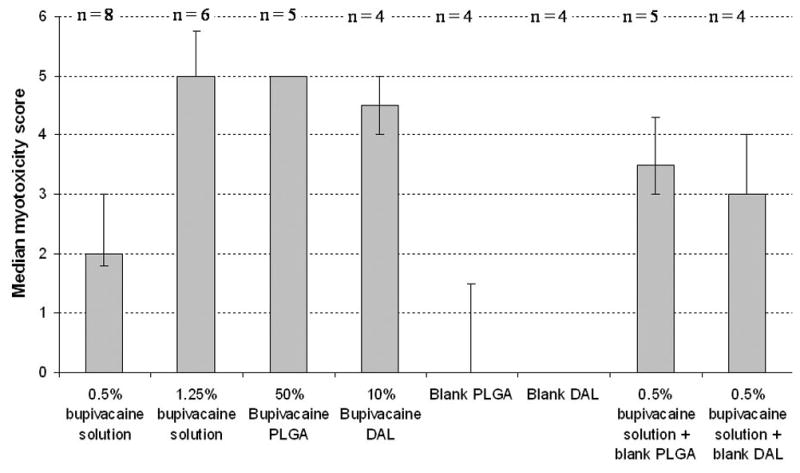

Animals were injected with 0.5% w/v bupivacaine hydrochloride, 10% w/w bupivacaine DAL particles or 50% w/w bupivacaine PLGA microspheres (Table 1). The sensory and motor blocks, from encapsulated bupivacaine were longer than those from free bupivacaine. On gross dissection, tissues injected with free drug appeared normal. In the other groups, particles were found in discrete pockets adjacent to the sciatic nerve, but the tissue appeared otherwise normal. On histological examination, there was evidence of perifascicular myotoxicity in all animals. The injury was limited to the site of injection, at the surface cell layers of the muscle adjacent to the depot of particles. It was considerably more pronounced in animal injected with encapsulated bupivacaine than with bupivacaine solution, both in extent (Fig. 1) and in severity (Fig. 1, Fig. 2; p = 0.002 for comparison of 0.5% w/v bupivacaine to 50% w/w bupivacaine PLGA microspheres; p = 0.004 for comparison to 10% w/w bupivacaine DAL particles; both by Mann-Whitney U-tests with α = 0.005; sample sizes are given in Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Durations of nerve blockade (min) from local anesthetic formulations

| Treatment | Sensory | Motor | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bupivacaine 0.5% w/v | 188 (154 – 195) | 189 (177 – 209) | 0.18 |

| Bupivacaine 50% w/w PLGA microsphere | 613 (474 – 944) | 711 (584 – 1306) | 0.046 |

| Bupivacaine 10% w/w DAL | 251 (219 – 285) | 348 (296 – 501) | 0.07 |

| Bupivacaine 1.25 % w/v | 266 (235 – 285) | 293 (288 – 301) | 0.028 |

| Bupivacaine 0.5% w/v + blank PLGA microsphere | 152 (140 – 167) | 183 (177 – 197) | 0.028 |

| Bupivacaine 0.5% w/v + blank DAL | 98 (21 – 163) | 168 (41 – 175) | 0.14 |

Data are medians with 25th and 75th percentiles. P-values compare the durations of sensory and motor block in animals in the same group, and result from a Wilcoxon signed ranks test. DAL = DPPC-albumin-lactose particles. PLGA = poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid. w/v = weight per volume. w/w = weight per weight. n = 6 for all groups except n = 4 for bupivacaine 10% w/w DAL.

α = 0.05

Fig. 1.

Mytotoxicity (MTox) from injection of 10% (w/w) bupivacaine microparticles (DAL). A. Low-magnification view (100X) showing inflammation in the area of injection of the particles, between the sciatic nerve (SN) and muscle. B. High magnification view (200X) of severe perifascicular myotoxicity adjacent to the microparticles (which are not visible) in a separate animal. “M” denotes muscle.

Fig. 2.

Myotoxicity scores (see Methods) in animals injected with various local anesthetic and/or microparticulate formulations. Data are medians with 25th and 75th percentiles. The sample sizes for each group are denoted at the top of the chart. “Blank” signifies particles without bupivacaine.

The role of burst release

Many particulate formulations display a rapid initial release of drug referred to as “burst” release. However, comparison of the release kinetics between the particle types reveals that the peak rate of the burst is not the only or perhaps not even the main consideration in myotoxicity. Fifty mg of bupivacaine-containing DAL particles or PLGA microspheres were suspended in 1 ml of saline, placed in dialysis tubes, and the release of drug was measured as described in Methods. The release from particles was compared to that from 1 ml of 0.5% w/v bupivacaine hydrochloride. Figure 3 shows the rate of bupivacaine release from those samples per hour over time. Free 0.5% w/v bupivacaine caused a much higher peak level of drug than the other two formulations, yet 0.5% w/v bupivacaine causes little myotoxicity in vivo (Fig. 2) and as previously described 22,23, while the encapsulated formulations do (Figs. 1 and 2, and ref. 17). Therefore, the magnitude of the peak level of bupivacaine released is not the sole determinant of myotoxic potential. In contrast, the encapsulated formulations caused severe myotoxicity despite lower peak release rates, suggesting that injury may be a product of a critical concentration applied over time.

Fig. 3.

Release rate of bupivacaine over time from bupivacaine hydrochloride solution, DAL particles, and PLGA microspheres. Data are means with standard deviations (n = 4 in each group). Note that the data represent the rate of bupivacaine release, i.e. the amount of bupivacaine released during an interval divided by the duration of that interval, and are not cumulative.

This is not to suggest that the magnitude of the burst release is irrelevant. The total amount of drug in 0.5% w/v bupivacaine solution is considerably less than that contained in the particles. To demonstrate the potential effects of rapid release of particle contents, six animals were injected with an aqueous solution containing a quantity and volume of bupivacaine equal to the total contained in the DAL formulation, i.e. 0.6 ml of 1.25% w/v bupivacaine. The duration of sensory block was longer than that from 0.5% w/v bupivacaine (Table 1; p = 0.004 by Mann-Whitney U-test; α = 0.05, sample sizes in table). On dissection, the tissues appeared grossly normal. However, severe myotoxicity was seen in all samples (n = 6) on microscopic examination, comparable to that seen with the LSPSs (P > 0.05 by Mann-Whitney U-test; α = 0.005, sample sizes in Fig. 2), and signnificantly higher than that seen with 0.5% w/v bupivacaine (p = 0.002 by Mann-Whitney U-test; α = 0.005, sample sizes in Fig. 2). We did not perform an analogous experiment for the PLGA microspheres, as the amount of bupivacaine contained in 75 mg of those particles might cause severe systemic toxicity in a 350 g rat (100 mg/kg of bupivacaine); the dose of bupivacaine that kills 50% of adult rats (LD50) injected at the sciatic nerve is approximately 30 mg/kg 24.

The role of extended release

Local anesthetic-induced myotoxicity generally recovers rapidly, often within two weeks. However, we have noted that some controlled release formulations cause myotoxicity at least as far out as 1 month after injection 25. This is at a time when bupivacaine release from such microparticles has ended, following approximately three weeks of release at a rate that is too low to produce nerve blockade26. One possible explanation of this observation is that local anesthetic myotoxicity is time-dependent. To assess this hypothesis, we allowed cells from a myoblast cell line (C2C12 cells) to differentiate into myotubes, then exposed them to a range of concentrations of bupivacaine over a variety of time frames (2 and 6 hours; 1, 2, and 4 days; 1, 2, and 3 weeks; Fig. 4). Myotoxicity increased with the concentration of bupivacaine, but also markedly with duration of exposure. For example, 62 ± 12 % of cells exposed to 0.025% w/v bupivacaine survived a 2h exposure, while only 1 ± 2 % survived at 3 weeks (p ≪ 0.001 by Student t-test; α = 0.05; n = 12 per group). Concentrations of bupivacaine that would be expected to have little or no anesthetic efficacy, and that showed minimal toxicity over short durations of exposure, showed decreased viability over the course of days to weeks. For example, 88 ± 12 % of cells exposed to 0.0025% bupivacaine survived at 2 h, while 52 ± 13 % survived after 3 weeks (p ≪ 0.001 by Student t-test; α = 0.05; n = 12 per group).

Fig. 4.

A. Mean survival (z-axis) of C2C12 cells exposed to a range of concentrations of bupivacaine (y-axis) for 2 and 6 hours; 1, 2, and 4 days; 1, 2, and 3 weeks (z-axis). n = 12 for each point; standard deviations are not shown for the sake of clarity. The color code on the right reflects the % cell survival in the z-axis. Statistical inferences on the data are discussed in the text. B. Effect of 2 days of exposure of a range of bupivacaine concentratiosn on cell survival. Data are means with standard deviations. C. Effect of duration of exposure to on cytotoxicity of 0.025% w/v bupivacaine. Data are means with standard deviations. Note that both B and C are cross-sections of A.

The role of particles in myotoxicity

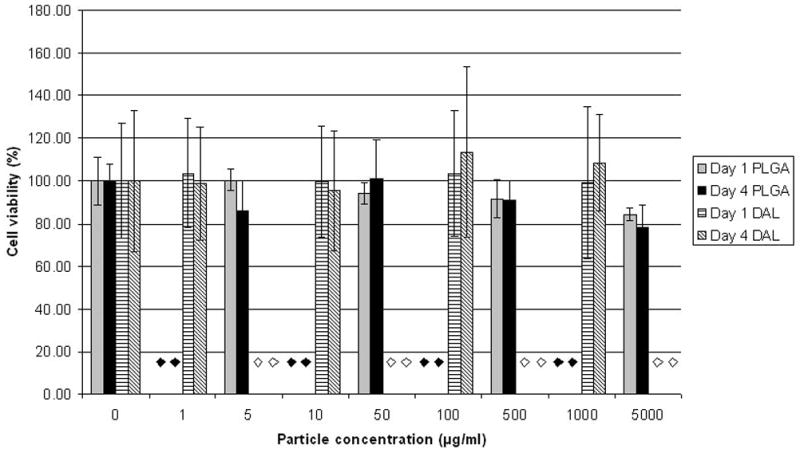

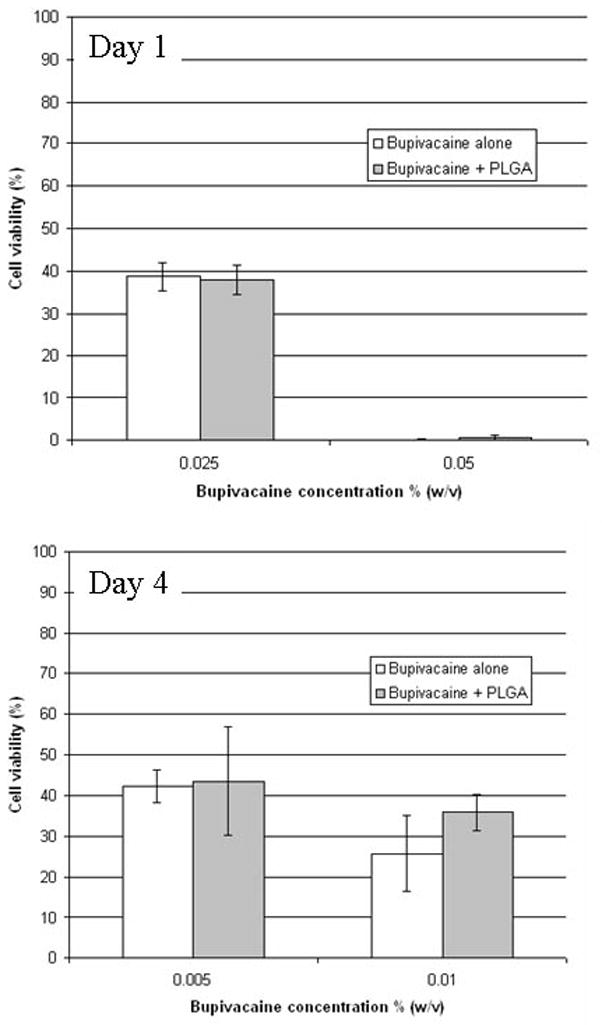

Blank (no bupivacaine) particles injected at the sciatic nerve caused relatively minimal myotoxicity when injected at the sciatic nerve (Fig. 2). This lack of toxicity was also seen in vitro: C2C12 cells exposed to DAL and PLGA particles displayed either minimal or no decrease in cell viability compared to untreated cells over a period of four days, even at very high concentrations (Fig. 5). (PLGA microspheres at 5000 μg/ml produced a small but statistically significant decrease in cell viability) To assess the possibility that the particles increase the toxicity of local anesthetics, C2C12 cells were incubated in local anesthetic solutions with or without particles. PLGA microspheres did not enhance the toxicity of various bupivacaine concentrations (Fig. 6). Survival in cells exposed to 0.05% w/v bupivacaine for 1 day and 0.01% bupivacaine for 4 days was statistically significantly higher in the groups that received particles as well, although the difference was small. Data showing that DAL particles do not increase bupivacaine myotoxicity are not shown.

Fig. 5.

Survival of C2C12 cells after 1 or 4 days of exposure to a range of concentrations of blank (no bupivacaine) particles. The diamonds denote concentrations of particles that were not tested (black – PLGA, white - DAL). Data are means with standard deviations (n = 8).

Fig. 6.

Survival of C2C12 cells after 1 or 4 days of exposure to bupivacaine solutions with or without blank (no bupivacaine) PLGA particles. Data are means with standard deviations (n = 8 in all groups). Groups with and without bupivacaine were compared by t-test; there were no differences.

Nonetheless, it is possible that particles have an indirect role in the development of myotoxicity. Animals were injected with 38 mg of blank (no bupivacaine) microparticles of both types which had been suspended in 0.3 ml of 0.5% w/v bupivacaine. On dissection, the tissue appeared mildly inflamed, and particles were located in discrete pockets in the vicinity of the nerve. Microscopy revealed inflammation and myotoxicity in areas adjacent to the pockets of particle. The median myotoxicity score was higher (Fig. 2) in these groups than in those injected with 0.5% w/v bupivacaine alone although this was not statistically significant by the stringent criteria used here (e.g. for PLGA microparticles suspended in bupivacaine solution, p = 0.016 by Mann-Whitney U-test; α = 0.005, sample sizes in Fig. 2). We note, however, that when the results for both particle types suspended in bupivacaine were pooled and compared to 0.5% bupivacaine, the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.004 by Mann-Whitney U-test; α = 0.005, n = 9 when combining the two particle-containing groups).

Discussion

The initial burst release of bupivacaine appears to cause myotoxicity, but only if the magnitude or some product of magnitude and duration of exposure are above a certain undefined threshold. This contribution to local injury is theoretically amenable to engineering, i.e. it should be possible to minimize that burst release. Of much greater concern is the observation that very low – even subanesthetic - concentrations of bupivacaine can become myotoxic over extended periods of time. This finding raises the possibility that myotoxicity could be an inevitable concomitant of long-term exposure to conventional (amino-amide and amino-ester) local anesthetics, irrespective of the technology used to deliver them. Myotoxicity is a well-known occurrence in clinical 19 or investigational 27 use of conventional local anesthetics. While it can have quite severe consequences 19, it has not generated much clinical concern. In fact, intramuscular local anesthetic injection is a standard treatment for trigger points in myofascial pain syndromes 28, and local anesthetic myotoxicity is generally reversible. The distinction that must be made, however, is that those treatments generally involve a single-shot drug injection with a brief duration, while microparticulate systems can result in very high local concentrations and/or weeks of local anesthetic exposure. An even greater concern is that local anesthetics also have considerable local neurotoxicity 29–31; the potential for controlled release devices to injure nerves has not been examined extensively, but injury to muscle suggests that nerve injury might also be possible. Of note, animals that achieved sciatic nerve blocks lasting approximately 9 days after injection with microparticles containing tetrodotoxin, bupivacaine, and dexamethasone frequently had one or more cycles of block recurrence after the initial block wore off 25, a pattern potentially attributable to nerve injury. We have also seen this pattern with high concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants used as local anesthetics 23, which have been shown to be highly neurotoxic 23,32.

The effect of the particles themselves on myotoxicity is difficult to explain fully. It would appear from our results here and from prior experience that the particles themselves cause little direct myotoxicity. However, the fact that the myotoxicity of bupivacaine solution is increased in the presence of particles in vivo suggests that they might enhance that toxicity. One possibility is that the particles release some agent (e.g. lactic or glycolic acids, residual organic solvent, excipients etc.) that potentiates local anesthetic toxicity, but our cell culture data do not support that conclusion. Another possibility is that the presence of discrete pockets of particles allows more reliable identification of sites where the local anesthetic was deposited, thus improving the accuracy of sampling. However, we do not see any sign of such severe toxicity in any animal injected with bupivacaine solution. Furthermore, we did not see such toxicity in an animal model specifically designed to remove sampling bias by injecting very large volumes of local anesthetic solutions (1.5 ml) 23. It is possible that the inflammation caused by the particles worsens myotoxicity by some unknown mechanism, perhaps by their pro-inflammatory effects 17,20,25. Finally, the macroscopic deposits of particles – as opposed to the individual particles - may slow the decline of the local concentration of drug, thereby increasing the toxicity of bupivacaine solution. The merits of the last two possibilities cannot be evaluated by the methods used in this study. The inflammatory response to particles may prove to be problematic in its own right, irrespective of myo- or neurotoxicity, given the large mass that may have to be injected to achieve clinically relevant nerve blocks in humans.

Although we cannot rule out the possibility that residual organic solvents from the particle production process contributed to the observed myotoxicity, it is unlikely that they play a major role. Particle of both types do not cause myotoxicity in the absence of local anesthetics 17. Furthermore, vehicles that do not involve organic solvents (e.g. cross-linked hyaluronic acid) only cause myotoxicity when they contain local anesthetics 8.

Myotoxicity appears to be related to both the release kinetics of bupivacaine (burst and duration of release), and perhaps the presence of the particles themselves. Even very low concentrations of bupivacaine appear to be myotoxic if the duration of exposure is sufficiently prolonged. One possible implication of these findings is that any type of prolonged duration local anesthesia using drugs of this type will be mytotoxic, and potentially neurotoxic.

Summary statement.

Local anesthetic-containing microparticles cause myotoxicity which is due to drug burst release, extended exposure, and, indirectly, to the presence of the particles.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: GM073626 (to DSK) from NIGMS (National Institute of General Medical Sciences).

References

- 1.Masters DB, Berde CB, Dutta SK, Griggs CT, Hu D, Kupsky W, Langer R. Prolonged regional nerve blockade by controlled release of local anesthetic from a biodegradable polymer matrix. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199308000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant GJ, Vermeulen K, Langerman L, Zakowski M, Turndorf H. Prolonged analgesia with liposomal bupivacaine in a mouse model. Reg Anesth. 1994;19:264–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mashimo T, Uchida I, Pak M, Shibata A, Nishimura S, Ingaki Y, Yoshiya I. Prolongation of canine epidural anesthesia by liposome encapsulation of lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:827–34. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowat JJ, Mok MJ, MacLeod BA, Madden TD. Liposomal bupivacaine. Extended duration nerve blockade using large unilamellar vesicles that exhibit a proton gradient. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:635–43. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199609000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma BB, Jain SK, Vyas SP. Topical liposome system bearing local anaesthetic lignocaine: preparation and evaluation. J Microencapsul. 1994;11:279–86. doi: 10.3109/02652049409040457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yanez AM, Wallace M, Ho R, Shen D, Yaksh TL. Touch-evoked agitation produced by spinally administered phospholipid emulsion and liposomes in rats. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:1189–98. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199505000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masters DB, Domb AJ. Liposphere local anesthetic timed-release for perineural site application. Pharm Res. 1998;15:1038–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1011978010724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia X, Colombo G, Padera R, Langer R, Kohane DS. Prolongation of sciatic nerve blockade by in situ cross-linked hyaluronic acid. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohane DS, Lipp M, Kinney RC, Lotan N, Langer R. Sciatic nerve blockade with lipid-protein-sugar particles containing bupivacaine. Pharm Res. 2000;17:1243–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1026470831256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Corre P, Le Guevello P, Gajan V, Chevanne F, Le Verge R. Preparation and characterization of bupivacaine-loaded polylactide and polylactide-coglycolide microspheres. Int J Pharm. 1994;107:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Corre P, Rytting JH, Gajan V, Chevanne F, Le Verge R. In vitro controlled release kinetics of local anaesthetics from poly(D,L-lactide) and poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. J Microencapsul. 1997;14:243–55. doi: 10.3109/02652049709015336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curley J, Castillo J, Hotz J, Uezono M, Hernandez S, Lim J-O, Tigner J, Chasin M, Langer R, Berde C. Prolonged regional nerve blockade. Injectable biodegradable bupivacaine/polyester microspheres. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1401–10. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199606000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estebe J-P, Le Corre P, Mallédant Y, Chevanne F, Leverge R. Prolongation of spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine-loaded (DL-lactide) microspheres. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:99–103. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199507000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakiyama N, Juni K, Nakana M. Preparation and evaluation in vitro of polylactic acid microspheres containing local anesthetics. Chem Pharm Bull. 1981;29:3363–68. doi: 10.1248/cpb.29.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wakiyama N, Juni K, Nakano M. Preparation and evaluation in vitro and in vivo of polylactic acid microspheres containing dibucaine. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982;30:3719–27. doi: 10.1248/cpb.30.3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohane DS, Plesnila N, Thomas SS, Le D, Langer R, Moskowitz MA. Lipid-sugar particles for intracranial drug delivery: safety and biocompatibility. Brain Res. 2002;946:206–13. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02878-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohane DS, Lipp M, Kinney RC, Anthony DC, Louis DN, Lotan N, Langer R. Biocompatibility of lipid-protein-sugar particles containing bupivacaine in the epineurium. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:450–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pere P, Watanabe H, Pitkanen M, Wahlstrom T, Rosenberg PH. Local myotoxicity of bupivacaine in rabbits after continuous supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:304–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan Q, Dotson R, Erickson S, Kettler R, Hogan K. Local anesthetic myotoxicity: a case and review. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:942–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199404000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson JM. In vivo biocompatibility of implantable delivery systems and biomaterials. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1994;40:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohane DS, Yieh J, Lu NT, Langer R, Strichartz GR, Berde CB. A reexamination of tetrodotoxin for prolonged duration local anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:119–31. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199807000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padera R, Tse J, Bellas E, Kohane DS. Tetrodotoxin for prolonged local anesthesia with minimal myotoxicity. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:747–53. doi: 10.1002/mus.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnet C, Louis DN, Kohane DS. Tissue injury from tricyclic antidepressants used as local anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1838–43. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000184129.50312.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohane DS, Sankar WN, Shubina M, Hu D, Rifai N, Berde CB. Sciatic nerve blockade in infant, adolescent, and adult rats: a comparison of ropivacaine with bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1199–208. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199811000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohane DS, Smith SE, Louis DN, Colombo G, Ghoroghchian P, Hunfeld NG, Berde CB, Langer R. Prolonged duration local anesthesia from tetrodotoxin-enhanced local anesthetic microspheres. Pain. 2003;104:415–21. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo J, Curley J, Hotz J, Uezono M, Tigner J, Chasin M, Wilder R, Langer R, Berde C. Glucocorticoids prolong rat sciatic nerve blockade in vivo from bupivacaine microspheres. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:1157–66. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199611000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benoit PW, Yagiela A, Fort NF. Pharmacologic correlation between local anesthetic-induced myotoxicity and disturbances of intracellular calcium distribution. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1980;52:187–98. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(80)90105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwama H, Ohmori S, Kaneko T, Watanabe K. Water-diluted local anesthetic for trigger-point injection in chronic myofascial pain syndrome: evaluation of types of local anesthetic and concentrations in water. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:333–6. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2001.24672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalichman MW, Powell HC, Myers RR. Pathology of local anesthetic-induced nerve injury. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1988;75:583–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00686203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalichman MW, Moorhouse DF, Powell HC, Myers RR. Relative neural toxicity of local anesthetics. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993;52:234–40. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bainton CR, Strichartz GR. Concentration dependence of lidocaine-induced irreversible conduction loss in frog nerve. Anesthesiology. 1994;91:657–67. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199409000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estebe JP, Myers RR. Amitriptyline neurotoxicity: dose-related pathology after topical application to rat sciatic nerve. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1519–25. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200406000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]