Abstract

Lasonolide A is a novel polyketide displaying potent anticancer activity across a broad range of cancer cell lines. Here, an enantioselective convergent total synthesis of the (–)-lasonolide A in 16 longest linear and 34 total steps is described. This approach significantly reduces the step count compared to other known syntheses. The synthetic strategy utilizes alkyne-bearing substrates as core building blocks and is highlighted by stitching together two similarly complex halves via a key Ru-catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling and macrolactonization.

Lasonolides are polyketides extracted from the Caribbean marine sponge, Forcepia sp. To date, seven lasonolides (A-G) have been isolated from their natural source.1,2 In 1994, lasonolide A was submitted to cytotoxicity testing and profiling in the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) 60-cell panel screen. This screen confirmed that lasonolide A was highly potent toward a broad range of cancer cell lines and that this cytotoxicity stemmed from a unique mechanism of action,3 which still has not been fully elucidated.4 Due to its scarcity from its natural source and its unique mechanism of action, numerous synthetic studies have been directed towards the lasonolides.5-14 These efforts have led to four successful total syntheses of lasonolide A.15-20 Despite these efforts, research into the molecule's pharmacology has been hampered due to the extremely limited availability of the sponge and difficulty in performing lengthy chemical syntheses.21 These aspects make a compelling case for the evolution of a more step22 and atom economic23 synthesis of lasonolide.

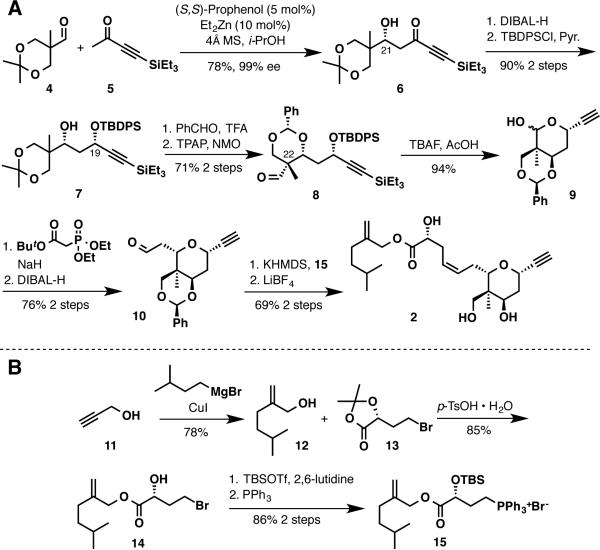

Lasonolide A consists of a 20-membered macrolide that contains a skipped 1,4-diene, and two highly substituted tetrahydropyran rings. The design of our synthetic plan (Scheme 1) relied on the utilization of alkynes for the assembly of two challenging subunits within the macrolide. The first was the formation of the C12-C13 trisubstituted olefin, and the second was for the key alkene-alkyne coupling, which would join fragments 2 and 3 while simultaneously forging the skipped 1,4-diene. One unique aspect of the proposed coupling is its propensity to generate branched 1,4-diene products; whereas, for this application, a linear diene is required. While use of this method to generate a linear diene has not been demonstrated in a complex molecule synthesis, the prospect that such regioselectivity may occur in some circumstances (vide infra),24,25 led us to pursue this thought for the aforementioned target. This analysis identified alkyne 2 and alkene 3 as key building blocks, both containing similar levels of complexity.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis Plan for Lasonolide A

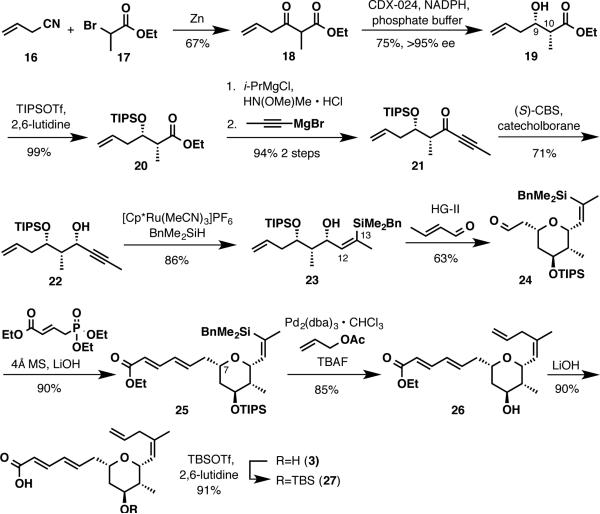

Alkyne 2 was prepared in a convergent manner (Scheme 2, A), and began with the construction of the tetrahydropyran ring. The formation of each new stereocenter on the tetrahydropyran ring was effected by utilizing the central C21 hydroxyl group as a stereo-chemical handle. This stereocenter was formed by a direct Zn/prophenol-catalyzed aldol26 addition between ynone 5 and aldehyde 4 to generate a β-hydroxyynone 6 in 78% yield and 99% ee. In a relay of stereochemical information, the C21 stereocenter directs the reduction of β-hydroxyynone 6 with DIBAL-H to furnish a 17:1 mixture of diastereomers favoring the syn 1,3-diol.27,28 The resulting propargylic alcohol can be selectively protected as a TBDPS ether affording 7 in 90% yield over the 2 steps.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of Alkyne Fragment

An efficient way to establish the C22 quaternary stereocenter utilizes the C21 hydroxyl group in a diastereoselective transacetalization reaction.19 To achieve this objective, acetonide 7 was treated with TFA and an excess of benzaldehyde in CHCl3 for an extended period of time (18 h). As a result, the formation of the desired acetal occurred in good yield with 5:1 chemoselectivity and 10:1 diastereoselectivity. Further, the undesired isomers could be separated by column chromatography and recycled to provide additional product. After two cycles, the desired acetal, containing the newly formed C22 quaternary stereocenter, could be isolated in 93% yield.

Continuing with the synthesis of 2, oxidation of the primary neopentylic alcohol was accomplished using TPAP/NMO29 to furnish aldehyde 8 in 76%. Removal of the silyl groups with TBAF generated lactol 9 in excellent yield. Gratifyingly, Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of lactol 9 spontaneously formed the desired tetrahydropyran ring as a single diastereomer in 91% yield. The excellent diastereoselectivity of this transformation reasonably arose from the reversible nature of the conjugate addition, which allowed for the formation of the thermodynamic product, the cis-2,6-substituted tetrahydropyran. Direct reduction of the tert-butyl ester with DIBAL-H delivered aldehyde 10 in 83% with no issues of overreduction.

The synthesis of the side chain 15 (Scheme 2, B) commenced with the carbocupration of propargyl alcohol and isoamylmagnesium bromide to generate allylic alcohol 12 in 78% yield. In contrast to previous syntheses, which required multiple steps to access this same compound, this approach demonstrates the benefits of alkyne building blocks. Transesterification of known ester 13 with allylic alcohol 12 provided α-hydroxy allylic ester 14.19 The secondary alcohol was subsequently converted to its TBS ether and the phosphonium salt was obtained by nucleophilic substitution of the alkylbromide with triphenylphosphine.

With phosphonium salt 15 in hand, the Wittig olefination with aldehyde 10 proceeded uneventfully in high yield as a single geometric isomer. Interestingly, removal of the benzylidene acetal turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. The acetal was resistant to hydrolysis with a variety of Brønsted acids, which included HCl, CSA, and TsOH. On the other hand, LiBF4 cleanly facilitated the removal of the benzylidene acetal,30 along with the inconsequential cleavage of the TBS ether, providing the target fragment alkyne 2 in 80% yield.

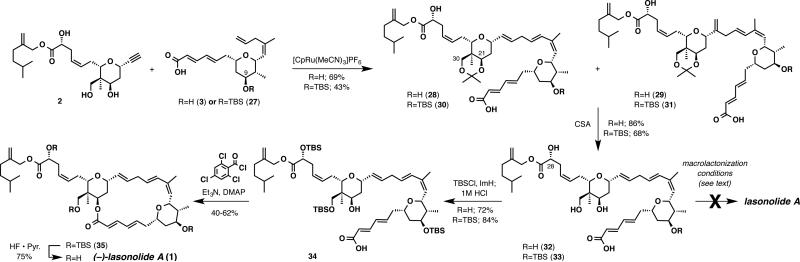

The synthesis of alkene 3 was pursued as illustrated in Scheme 3. Initial efforts were dedicated to establishing the absolute stereochemistry of the fragment by an enzymatic dynamic kinetic asymmetric reduction.31 After extensive screening it was found that β-ketoester 18, readily available from a Blaise reaction between α-bromo ester 17 and allyl cyanide 16, could be reduced to the corresponding β-hydroxyester (19) as a 4:1 mixture of syn:anti diastereomers (75%). The enantiomeric excess of the major syn diastereomer was measured to be >95% by chiral GC analysis. It is worth noting that careful control of the reaction pH (4.5) proved to be essential in order to avoid the undesired olefin isomerization.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Alkene Fragment

β-Hydroxyester 19 was converted to ynone 21 in three straightforward steps, which included TIPS protection of the secondary alcohol, conversion of the ethyl ester into a Weinreb amide and formation of the ynone by addition of 1-propynylmagnesium bromide.32 (S)-CBS catalyzed reduction of ynone 21 afforded the syn-syn-stereotriad (22) in 71% yield and in >20:1 diastereoselectivity. The use of freshly distilled catecholborane in nitroethane as solvent33 was critical to ensure high diastereoselectivity and yield for this transformation. Additionally, at this stage, the all syn isomer could be isolated from the undesired stereoisomers generated from the enzymatic reduction.

An equivalent of a trans hydro-alkylation under development in our laboratories was envisioned to access the C12–C13 (Z)-trisubstituted alkene. The sequence began with a Ru-catalyzed hydrosilylation34 of propargylic alcohol 22 to generate the desired trisubstituted (Z)-vinylsilane 23 with high levels of geometric selectivity (>15:1), in 86% yield. Formation of the substituted tetrahydropyran ring was effected through a simultaneous Hoveyda-Grubbs 2nd generation catalyzed cross metathesis/oxa-Michael sequence between alkene 23 and crotonaldehyde.35 The reaction proceeded with high diastereoselectivity (dr >20:1) and the desired cis-2,6-substituted tetrahydropyran (24) was isolated in 63% yield.36

Elaboration of the aldehyde into an (E, E)-dienoate moiety was envisioned using a Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination. Initial attempts using KHMDS as a base provided the desired dienoate accompanied with extensive epimerization at C7 (dr=1:1), presumably arising from a retro Michael/Michael reaction. Changing the base to LDA reduced the epimerization and 25 was obtained as a 85:15 mixture of diastereomers at C7. Gratifyingly, it was found that the use of LiOH and 4Å molecular sieves20 was superior in minimizing substrate epimerization and the desired dienoate could be obtained as a 10:1 mixture of diastereomers.37 The Pdcatalyzed sp2-sp3 Hiyama coupling38-40 between the vinyl silane 25 and allyl acetate delivered 1,4-diene 26 in 85% yield. Finally, saponification of the ethyl ester with lithium hydroxide furnished the desired alkene fragment (3).

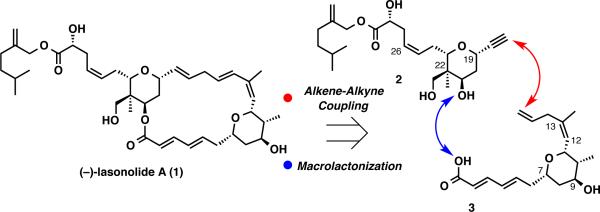

Having both alkene 3 and alkyne 2 in hand, the key alkene-alkyne coupling was explored. Insights from model studies, employing the [CpRu(MeCN)3]PF6 catalyst, suggested that there was a significant solvent effect associated with both reactivity and the linear to branched selectivity. Reactions run in chlorinated solvents (CH2Cl2 and dichloroethane) typically showed little to no evidence of alkene-alkyne coupling. When DMF was used as solvent the desired coupling reaction proceeded, however poor linear to branched product ratios were observed. Acetone was found to be the optimal solvent generally delivering the products in good yield with reasonable linear to branched ratios. In this way, an approximately 2:1 linear:branched product was obtained as an acetonide between the C21 and C30 hydroxyl groups in 69% yield (82% brsm). Formation of the acetonide was determined to precede the alkenealkyne coupling event and most likely results from the Lewis acidity of the cationic ruthenium catalyst. The excellent chemoselectivity of this process is illustrated by the tolerance of the dense array of functionality on alkyne 2 and alkene 3 under the reaction conditions, which is a testament to the mildness of the Rucatalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling reaction.

Efforts to increase the linear to branched selectivity24,25 by varying the reaction conditions proved ineffective. However, a positive effect was observed by incorporating a TBS protecting group on the C9 hydroxyl group, which increased the linear to branched selectivity to 3:1 in 43% yield.

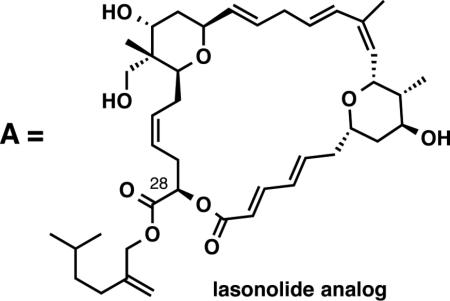

Completion of lasonolide A was accomplished from both 28 and 30 and each reaction sequence is presented in Scheme 4.41,42 Hydrolysis of the acetonide with CSA in methanol afforded the corresponding triol 32 and tetraol 33. Unfortunately, lasonolide A was never observed from the direct macrolactionization of tetraol 32 utilizing several macrolactonization reagents (i.e. Yamaguchi and Mukaiyama) under various reaction conditions. These reactions generally resulted in the decomposition of the starting seco acid. Interestingly, use of the Shiina reagent led to the selective formation of a macrolide,43 arising from a cyclization of the carboxylic acid onto the C28 hydroxyl group, albeit in a low unoptimized 10% yield.44 The identity of this macro-lactone was verified by an independent synthesis.

Scheme 4.

Completion of the Synthesis of (–)-Lasonolide A

To circumvent this difficulty, a different macrolactonization precursor was designed. Protection of the least sterically hindered alcohols of both 32 and 33 as their TBS ethers, and in situ hydrolysis of the resulting TBS ester with HCl, delivered seco acid 34 in good yield. To our delight, when seco acid 34 was subjected to the Yamaguchi macrolactonization protocol, TBS protected lasonolide A (35) was generated in 40-62%.42 At this stage, the linear and branched isomers, generated from the alkene-alkyne coupling, were separable by column chromatography allowing for the isolation of pure TBS protected lasonolide A (35). Finally, global deprotection of the silyl groups with HF • Pyr15,16 furnished the target molecule (–)-lasonolide A (1) in 75% yield.

The synthetic (–)-lasonolide A along with the isomeric macrolactone analog, generated from this work, were screened against a variety of cancer cell lines.45 IC50 values for the DU145, HCT116 and MCF7 cell lines with our synthetic lasonolide A were consistent with the values previously reported from the NCI 60-cell panel screen. Biological testing also revealed that lasonolide A inhibits A2058, Adr-Res, BXPC3, H460, SK-BR-3, and KPL-4 cell lines at nM concentrations. The isomeric lasonolide analog A43 was significantly less active than lasonolide A in terms of its application to a broad range of cancer cell lines. Interestingly, it did exhibit nM activity against the HCT116 cell line with IC50 values equal to that of lasonolide A.

In conclusion, a concise synthesis of (–)-lasonolide A was completed in only 16 linear steps and 34 total steps (1.6% overall yield from allyl cyanide (16)) from commercially available starting materials, drastically reducing the step count compared to the previously known routes. This atom and step economical approach stems from the key role of alkynes as building blocks and intermediates. Furthermore, it features a key ruthenium catalyzed alkene-alkyne coupling leading to the less common linear product as the major isomer, which is the first demonstration of an intermolecular transformation of this type that favors the linear product in such a complex setting.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NIH (GM33049) for generous support to our programs. C.E.S., K.L.H., and A.H. are the recipients of NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards (GM101747, GM086093, and GM077840, respectively). We also thank Johnson-Matthey for generous gifts of palladium and ruthenium salts. We would like to thank Ranier Kalkofen for performing preliminary experiments. Finally, we are grateful to Codexis, Inc. for the generous donation of enzymes and Genentech (Gail Phillips, Vishal Verma and John Flygare) for screening the synthetic (–)-lasonolide A and lasonolide analog.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and analytical data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Horton PA, Koehn FE, Longley RE, McConnell OJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:6–015-6016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AE, Chen Y, Winder PL, Pitts TP, Pomponi SA, Longley RE. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:1–351–1355. doi: 10.1021/np040028e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alley MC, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Hursey ML, Czerwinski MJ, Fine DL, Abbott BJ, Mayo JG, Shoemaker RH, Boyd MR. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5–89–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prommier et al have indicated that lasonolide A is a reversible inducer of chromosome condensation at all phases of the cell cycle. However, they have not been able to identify the cellular target of lasonolide A. Zhang Y-W, Ghosh AK, Pommier Y. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:4–424-4435. doi: 10.4161/cc.22768.

- 5.Ghosh AK, Ren G-B. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:2–559–2565. doi: 10.1021/jo202631e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deba T, Yakushiji F, Mitsuru S, Shishido K. Synlett. 2003;10:1–500–1502. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimura T, Bando T, Shindo M, Shishido K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:9–241–9244. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurjar MK, Kumar P, Rao BV. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8–617–8620. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurjar MK, Chakrabarti A, Rao BV, Kumar P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:6–885–6888. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowakowski M, Hoffmann HMR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:1–001–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck H, Hoffmann HMR. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999;11:2–991–2995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart DJ, Patterson S, Unch JP. Synlett. 2003;9:1–334–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalgrad JE, Rychnovsky SD. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1–589–1591. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawant KB, Ding F, Jenings MP. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:9–39–942. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee E, Song YH, Kang JW, Kim D-S, Jung C-K, Joo JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3–84–385. doi: 10.1021/ja017265d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song HY, Joo JM, Kang JW, Kim D-S, Jung C-K, Kwak HS, Park JH, Lee E, Hong CY, Jeong SW, Jeon K, Park JH. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:8–080–8087. doi: 10.1021/jo034930n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh AK, Gong G. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1–437–1440. doi: 10.1021/ol0701013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghosh AK, Gong G. Chem. Asian J. 2008;3:1–811–1823. doi: 10.1002/asia.200800164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang SH, Kang SY, Kim CM, Choi H.-w., Jun HS, Lee BM, Park CM, Jeong JW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:4–779–4782. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimura T, Yakushiji F, Kondo S, Wu X, Shindo M, Shishido K. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4–75–478. doi: 10.1021/ol0527678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isbrucher RA, Guzman EA, Pitts TP, Wright AE. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2009;331:7–33–739. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wender PA, Verma VA, Paxton TJ, Pillow TH. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:4–0–49. doi: 10.1021/ar700155p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trost BM. Science. 1991;254:1–471-1477. doi: 10.1126/science.1962206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trost BM, Toste FD, Pinkerton AB. Chem. Rev. 2005;101:2–067–2096. doi: 10.1021/cr000666b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trost BM, Frederiksen MU, Rudd MT. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6–630–6666. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trost BM, Fettes A, Shireman BT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2–660–2661. doi: 10.1021/ja038666r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiyooka S,-j., Kuroda H, Shimasaki Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:3–009–3012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohr P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:2–219–2222. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ley SV, Norman J, Griffith WP, Marsden SP. Synthesis. 1994;7:6–39–666. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipshutz BH, Pegram JJ, Morey MC. Synth. Commun. 1982;12:267–277. b For a recent example of benzylidene acetal hydrolysis using LiBF4 in a complex setting see: Araoz R, Servent D, Molgo J, Iorga BH, Fruchart-Gaillard C, Benoit E, Gu Z, Stivala CE, Zakarian A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:10499–10511. doi: 10.1021/ja201254c.

- 31.For examples of enzymatic dynamic kinetic asymmetric reduction of β-ketoesters see: Fauve A, Veschambre H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:5037–5040.Kawai Y, Takanobe K, Ohno A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1995;68:285–288.

- 32.Williams JM, Jobson RB, Yasuda N, Marchesini G, Dolling U-H, Grabowski EJJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5–461–5464. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu C-M, Kim C, Kweon JH. Chem. Commun. 2004;21:2–494–2495. doi: 10.1039/b407387h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trost BM, Ball ZT, Joge T. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:3–415–1418. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garber SB, Kingsbury JS, Gray BL, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8–168-8179. [Google Scholar]

- 36.For an example of a cross metathesis/oxa-Michael addition to from a tetrahydropyran see: Fuwa H, Noto K, Sasaki M. Org. Lett. 2012;12:1636–1639. doi: 10.1021/ol100431m.

- 37.These diastereomers become separable after the macrolactonization.

- 38.Hiyama T, Hatanaka Y. Pure Appl. Chem. 1994;66:1–471–1478. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trost BM, Machacek MR, Ball ZT. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1–895–1898. doi: 10.1021/ol034463w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dey R, Chattopadhyay K, Ranu BC. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:9–461-9464. doi: 10.1021/jo802214m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.For clarity only the major (linear) isomer, from the alkenealkyne coupling, is drawn. In the case where R=H a 2:1 ratio of products is advanced and in the case of R=TBS a 3:1 ratio of products is advanced. The linear and branched isomers become separable after macrolactonization.

- 42.See supporting information for details.

-

43.

- 44.Shiina I, Kubota M, Oshiumi H, Hashizume M. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:1–822-1830. doi: 10.1021/jo030367x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.IC50 values for lasonolide A (1): A2058 (16.6 nM); Adr-Res (414.1 nM); BXPC3 (148.1 nM); DU145 (29.2 nM); HCT116 (9.8 nM); H460 (20.7 nM); MCF7 (47.4 nM); SK-BR-3 (40.2 nM); KPL-4 (39.4 nM). IC50 values for lasonolide analog (ref 43): A2058 (>1000 nM); Adr-Res (>1000 nM); BXPC3 (>1000 nM); DU145 (>1000 nM); HCT116 (12.0 nM); H460 (>1000 nM); MCF7 (>1000 nM); SK-BR-3 (>1000 nM); KPL-4 (>1000 nM).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.