Abstract

Objectives

Most critically ill adults have impaired decision-making capacity and are unable to consent to research. Yet, little is known about how Institutional Review Boards interpret the Common Rule’s call for safeguards in research involving incapacitated adults. We aimed to examine Institutional Review Board practices on surrogate consent and other safeguards to protect incapacitated adults in research.

Design, Settings, and Participants

A cross-sectional survey of 104 Institutional Review Boards from a random sample of U.S. institutions engaged in adult human subject research (response rate, 68%) in 2007 and 2008.

Interventions

None.

Measurements

Institutional Review Board acceptance of surrogate consent, research risks, and other safeguards in research involving incapacitated adults.

Main Results

Institutional Review Boards reported that, in the previous year, they sometimes (49%), frequently (33%), or very frequently (2%) reviewed studies involving patients in the intensive care unit. Six Institutional Review Boards (6%) do not accept surrogate consent for research from any persons, and 22% of Institutional Review Boards accept only an authorized proxy, spouse, or parent as surrogates, excluding adult children and other family. Institutional Review Boards vary in their limits on research risks in studies involving incapacitated adults: 15% disallow any research regardless of risk in studies without direct benefit, whereas 39% allow only minimal risks. When there was potential benefit, fewer Institutional Review Boards limit the risk at minimal (11%; p < .001). Even in populations at high risk for impaired decision making, many Institutional Review Boards rarely or never required procedures to determine capacity (13%–21%). Institutional Review Boards also varied in their use of independent monitors, research proxies, and advanced research directives.

Conclusions

Much variability exists in Institutional Review Board surrogate consent practices and limits on risks in studies involving incapacitated adults. This variability may have adverse consequences for needed research involving incapacitated adults. Clarification of current regulations is needed to provide guidance.

Keywords: research ethics, third-party consent, research ethics committee, informed consent, proxy

In the United States, the Belmont Report identified three ethical principles that underlie the Common Rule and guide Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) in their efforts to protect human subjects in research: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice (1). Respect for persons requires that informed consent be obtained for research participation and that special protections are given to protect persons with diminished autonomy. It is now recognized that many older adults with acute illnesses may be incapacitated and unable to consent to research. During acute illness, 26% to 67% of elderly patients, 32% of patients with acute myocardial infarction, and 14% of patients with diabetes have impaired cognition (2–7). Delirium and dementia, common contributors to decisional impairment among hospitalized patients, are more common among the elderly (8–11). As the population ages, the number of U.S. adults with dementia is expected to increase to 13.2 million by 2050 (12), and the number of potentially incapacitated adult patients in the hospital will likely increase. In the intensive care unit (ICU), most of the patients are impaired in their decision-making and unable to consent to research. Yet, the issue of how IRBs should best guide research that involves incapacitated adults is unclear.

The Common Rule allows for informed consent for research from the subject or the subject’s legally authorized representative, but it leaves the definition of surrogate to applicable state laws (13, 14). Unfortunately, most states have no laws regarding surrogate consent for research, and reliance on health care proxies is problematic because most elderly individuals do not have a legally authorized representative for medical decision-making (15–17). Federal regulations also dictate that in research involving decisionally impaired adults, “additional safeguards” should be included to protect this vulnerable population (18). However, the regulations are silent about the nature of these safeguards.

A number of national, state, and international bodies, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Bioethics Advisory Commission, have proposed guidelines for research involving incapacitated individuals. These guidelines describe six possible safeguards: assessment for competence to consent, demonstration that research cannot be performed without enrolling incapacitated adults, use of surrogate decision-makers with evidence of the patient’s previous preferences depending on research risk, institutional assessment of the research risk and benefit to ensure that they are appropriate, a requirement for assent or dissent from participants, and a requirement for independent consent and participation monitors to ensure that research participation is consistent with the patient’s preferences (19). However, there is debate about the specifics, necessity, and implementation of these safeguards. The resulting confusion has led to a working group convened by the Office of Human Research Protection to make recommendations with regard to research involving decisionally impaired adults (Subcommittee for the Inclusion of Individuals with Impaired Decision-Making in Research) (20).

Consequently, it is not clear how IRBs handle research involving incapacitated adults. In this study, we examined the variability of IRB practices with regard to surrogate consent and other safeguards implemented to protect incapacitated adults, including ICU patients, in research. Understanding the scope of IRB practices with this population is especially timely and important given the increasing age of the population and the current discussions of how best to protect this group of vulnerable individuals.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Population

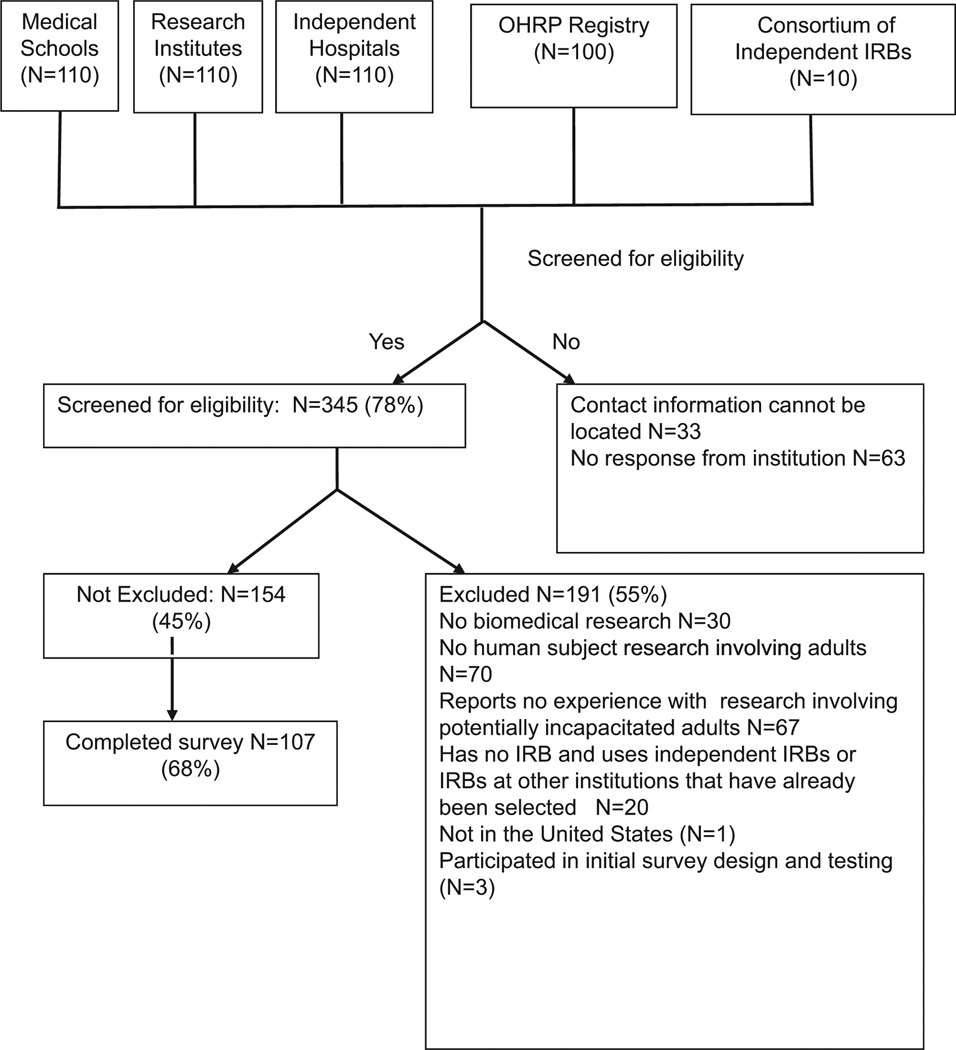

IRBs (n = 440) were randomly selected from three sources for screening (Fig. 1): medical schools (n = 110), research institutions (n = 110), and hospitals (n = 110) that received NIH funding in 2005 (http://report.nih.gov/award/HistoricRankInfo.cfm); institutions with IRBs registered under the Office of Human Research Protection (n = 100) (http://ohrp.cit.nih.gov/search/); and members of the Consortium of Independent IRBs (n = 10). The IRB chairpersons of 345 institutions (78%) were successfully contacted and screened. In institutions with multiple IRB chairpersons, only one was enrolled. If the IRB chair was not available or did not feel qualified to complete the survey, then that person was asked to refer us to another available knowledgeable IRB member.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) selected and enrolled for survey. OHRP, Office of Human Research Protection.

Institutions that do not conduct biomedical or adult human subject research or that have no experience with research involving potentially incapacitated adults were excluded (Fig. 1). Institutions located outside of the United States were excluded. Twenty institutions had no IRB but used either an independent IRB or an IRB at another institution that already had been selected for the study.

Survey Development and Administration

The structured survey was developed after a review of literature and a focus group of four IRB members from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. The survey was evaluated for clarity and for face and content validity by three of the investigators (MNG, GW, JHS) and tested on two randomly selected IRB chairpersons. After the first two respondents, some questions were revised for clarity and an additional question about who the IRB would accept as surrogate for research decision making was added. No subsequent changes to the survey were made. Trained research personnel administered the surveys by telephone according to a written script. Nine respondents completed an online survey via SurveyMonkey.com. There was no difference between online and telephone participants in their institutions’ academic status, region of the United States, NIH funding, respondents’ years of service with IRB or experience with studies involving incapacitated patients, or frequency of unsure answers (p ≥ .2). The study was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine IRB.

To determine how well the respondents’ answers reflected their institutional policies, we acquired IRB guidelines through internet searches and personal requests for 36 of 104 (35%) participating institutions. Only 30 guidelines mentioned procedures regarding cognitively impaired adults, such as the acceptability of surrogate consent, hierarchy of acceptable surrogates, permissibility of studies with no direct benefit, and other safeguards that may be used to protect incapacitated adults. Among the 300 survey questions whose answers can be found in the IRB guidelines, only nine (3%) differed from the written IRB protocol. One response referred to the acceptability of surrogate consent for research, two responses referred to accepted procedures to determine capacity to consent, four responses referred to who may serve as acceptable surrogates, and two responses referred to the permissibility of minimal risk studies with no benefit.

IRB Acceptance of Surrogate Consent for Research

We asked each IRB respondent, “In your best judgment, if the research involves incapacitated adults AND requires informed consent, would your IRB accept permission from the patient’s surrogate or proxy to enroll the patient in lieu of the patient’s consent at least some of the time?”

Risk-Benefit Ratio Allowed by IRB in Studies Involving Incapacitated Adults

Respondents were presented with different risk-to-benefit ratios in research that would require informed consent or a waiver of informed consent and were asked whether their IRB would permit research studies to include incapacitated subjects. They were asked about minimal risk, minor increase over minimal risk, or more than minor increase over minimal risk studies with and without potential direct benefit.

The Common Rule defines minimal risk as the level of risk at which “the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the research are not greater in and of themselves than those ordinarily encountered in daily life or during the performance of routine physical or psychological examinations or tests” (14). However, minor increase and more than minor increase over minimal risk are not explicitly defined by the Common Rule. The National Human Research Protections Advisory Committee attempted to clarify research risk in pediatric research and referred to minor increase over minimal risk as “a bit more than (minimal risk) and also commensurate with the risks of interventions or procedures having been experienced or expected to be experienced in the lives of children with a specific disorder or condition” (21). An excellent discussion of the federal regulations and interpretation of research risks in adults and children and the informed consent process is available (22).

Given the lack of clear definitions on risk categories, IRBs may vary in their opinions about what constitutes minimal risk (23). Thus, we asked the IRBs to categorize the risk of the following procedures in research involving critical care patients in the ICU: collection of a 10-mL tube of blood for protein analysis, collection of a 10-mL tube of blood for a genetic epidemiology study, one computed tomography scan of the chest, and treatment with a drug with a 3.5% chance of serious bleeding. We explained that the genetic study involved testing for common polymorphisms in genes that may predict increased risk for common diseases such as diabetes. Respondents could answer minimal risk, minor increase over minimal risk, or more than minor increase over minimal risk.

Safeguards Used in Studies Involving Incapacitated Adults

Participants were asked how frequently their IRBs used certain safeguards in studies involving incapacitated adults (19). The safeguards are placed into three main domains: 1) assessment of the capacity to consent to research, 2) safeguards to protect the incapacitated subject in research, and 3) safeguards to protect subjects who are likely to lose decision-making capacity during the course of the study.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± 1 sd or median (25%–75%), depending on normality. Exploratory analyses between groups were performed using Fisher’s exact tests, analysis of variance, or Wilcoxon rank-sum as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p < .05. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.13; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of the 345 institutions screened for the study, 157 were eligible and 107 completed the survey, for a response rate of 68%. Participation in the survey did not differ significantly with the type of institution (medical school, research institute, hospitals, independent IRBs) or NIH funding (p > .1). Three IRBs, including Mount Sinai, participated in the initial design of the survey, and their surveys were not included in the final analysis. The results presented are from the remaining 104 IRBs.

Baseline characteristics of the respondents and their institutions are detailed in Table 1. Respondents tended to be experienced IRB members and were mostly chairpersons and directors with a median of 7 yrs of experience (25%–75% with 5–13 yrs). Most were at academic medical centers (75%) or community-based nonacademic hospitals (12%). Institutions from 36 states plus Washington, DC and Puerto Rico participated.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of respondents and their institutions (n = 104)

| Characteristics of respondents | |

| Female, No. (%) | 38 (37%) |

| Age (mean ± sd) | 52 ± 10 |

| Title within IRB, No. (%) | |

| Chairperson | 63 (61%) |

| Vice-Chair | 3 (3%) |

| Administrative director | 19 (18%) |

| Administrator | 13 (13%) |

| IRB member/Officer | 6 (3%) |

| Othera | 3 (3%) |

| Occupation,b No. (%) | |

| Physician | 38 (39%) |

| Administrator/IRB Coordinator | 39 (38%) |

| Professor/Researcher | 12 (12%) |

| Nurse | 11 (11%) |

| Bioethicist | 4 (4%) |

| Pharmacist | 3 (3%) |

| Lawyer | 3 (3%) |

| Sociologist | 2 (2%) |

| Psychologist | 5 (5%) |

| Years on the IRB median (25%–75%) | 7 (5–13) |

| Characteristics of Institutions | |

| Type of Institution, No. (%) | |

| Academic medical school or center | 78 (75%) |

| Community-based hospital | 12 (12%) |

| Independent IRB | 6 (6%) |

| Research Institute | 4 (4%) |

| Government agency | 1 (1%) |

| Non-Medical School University | 3 (3%) |

| Medical care provided at institution, No. (%) | 92 (88%) |

| Region of United States, No. (%) | |

| Northeast | 36 (35%) |

| South | 31 (30%) |

| Midwest | 16 (16%) |

| West | 9 (9%) |

| National Institutes of Health funding ($), median (25%–75%) $26,317,646 ($2,423,436–$83,884,687) | |

| Number of active protocols reviewed in past yearc | |

| <500 | 41 (39%) |

| 500–1000 | 25 (24%) |

| >1000 | 36 (35%) |

| Number of different sites IRB overseesc | |

| <10 | 68 (65%) |

| 11–99 | 27 (26%) |

| 100–499 | 5 (5%) |

| 500–1000 | 1 (1%) |

| >1000 | 3 (3%) |

IRB, Institutional Review Board.

Other self-reported titles include Chief Executive Officer of National Physicians Cooperative using IRB of record, Regulatory Compliance Coordinator, and Research Ethics and Compliance Consultant;

total adds up to more than 100% because multiple answers were allowed;

two respondent did not know answer.

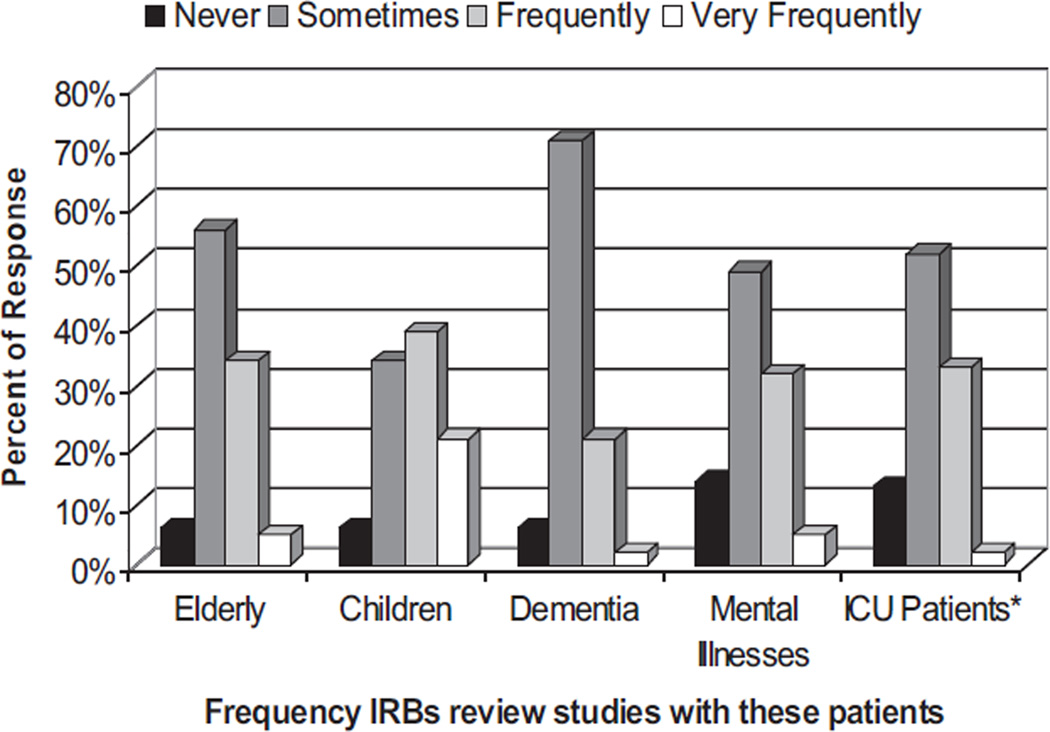

IRBs commonly reviewed studies involving populations at high risk for impaired decision making (Fig. 2). When asked how often they reviewed studies involving patients in the ICU in the past year, IRBs reported reviewing such studies sometimes (52%), frequently (33%), or very frequently (2%).

Figure 2.

Frequency with which Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) reviewed studies involving the patient populations at risk for impaired decision making. ICU, intensive care unit.

Surrogate Consent for Research

Six IRBs (6%) do not accept surrogate consent for research involving incapacitated adults (Table 2). Most IRBs would accept an authorized proxy (80%) defined as health care proxy, guardian, or power of attorney, spouse (83%), or parents (78%) as surrogates. Only 68% of IRBs would accept adult children as surrogates for research consent.

Table 2.

Limits to acceptable surrogates for research consent (n = 104)

| Acceptable Surrogates for Research Decision Making |

Yes, N (%) | No, N (%) | Unsure, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate accepted | 98 (94%) | 6 (6%) | — |

| Individuals allowed to consent to Research for incapacitated adults (n = 104)a | |||

| Authorized representative | 83 (80%) | 11 (11%) | 8 (8%) |

| Spouse | 86 (83%) | 15 (14%) | 1 (1%) |

| Parent | 81 (78%) | 14 (13%) | 7 (7%) |

| Adult children | 71 (68%) | 18 (18%) | 12 (12%) |

| Adult sibling | 57 (55%) | 33 (32%) | 12 (12%) |

| Adult grandchildren | 35 (34%) | 42 (40%) | 25 (24%) |

| Other adult family | 32 (31%) | 48 (46%) | 22 (21%) |

| Friend | 15 (14%) | 76 (73%) | 11 (11%) |

Two respondents report accepting surrogate consent but information on who can serve as surrogate is missing from the earliest surveys. Percentages do not add up to 100% because of rounding and the two respondents missing these responses.

There was considerable variability in surrogate consent practices between and within individual states; one or more IRBs from 16 states reported that surrogate consent is either not accepted or limited to health care proxies, spouse, or parents only (Supplemental Fig. 1 [see Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/A166]). At the time of the survey, only two states had laws regarding surrogate consent for research (California and Kansas). New Jersey passed a statute in 2008 after this survey was completed (24). Forty-two states have laws pertaining to surrogate decision making for medical treatment in the absence of a health care proxy and list adult children and other family as acceptable surrogates (24, 25). IRB acceptance of surrogate consent for research did not significantly depend on state surrogacy laws on health care decision making: 19 of 21 IRBs (86%) from states without surrogacy laws accepted surrogate consent for research vs. 80 of 83 IRBs (96%) from states with such laws (p = .1). Additionally, acceptance of adult children as surrogates for research did not differ between IRBs in states with (69%) and without (71%) surrogacy laws (p > .9). Although California has a law regarding surrogate consent for both medical treatment and research (26), one IRB did not accept surrogate consent and another restricted acceptable surrogate to the proxy or spouse only. It is not clear whether this reflects the lack of knowledge of the IRB about the law or the continuing unease of some IRBs after the controversy stemming from an Office of Human Research Protection investigation of this issue in California (27).

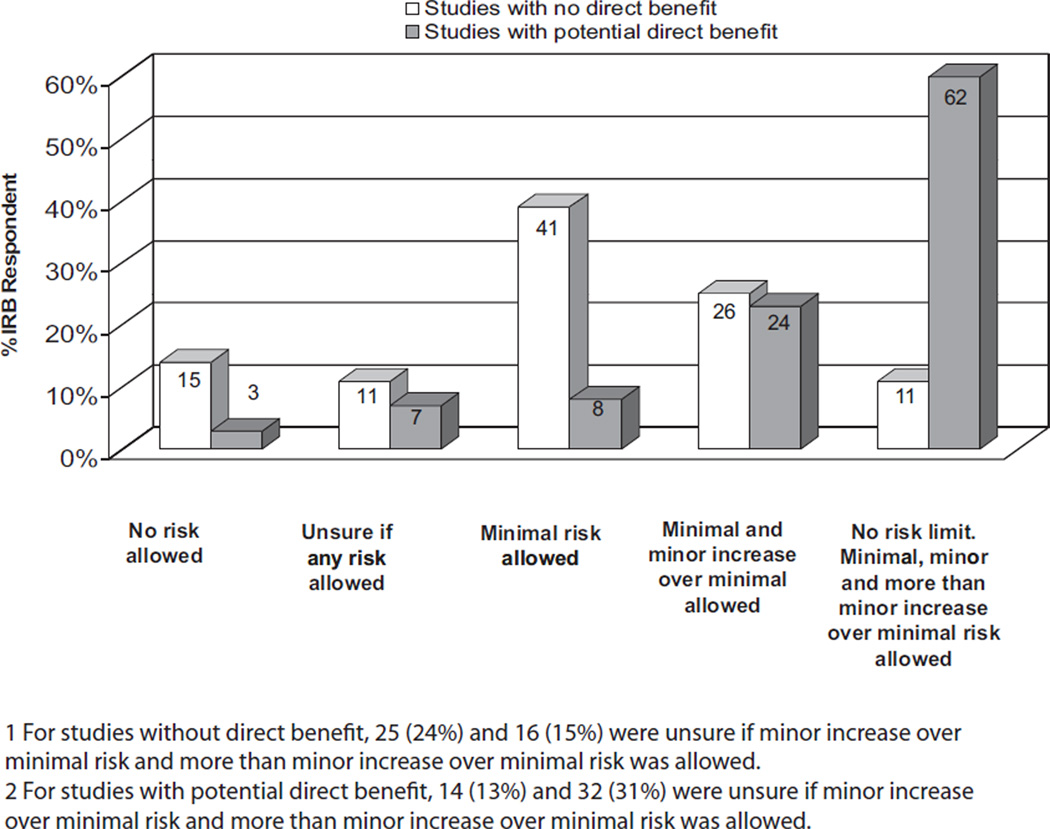

Risk-to-Benefit Ratio Allowed in Research Involving Incapacitated Adults

IRBs vary in what risk-to-benefit ratios are allowed in studies involving incapacitated adults (Fig. 3). For studies with no direct benefit, 14% of IRBs would not allow studies of any risk to involve incapacitated adults, whereas 11% were unsure if any study risk would be allowed. Forty-one (39%) IRBs would allow only minimal risk studies and 25% would allow a minimal and minor increase over minimal risk studies. Eleven (11%) have no limits on allowable research risks (Fig. 3), whereas in studies with potential for direct benefit, significantly more IRBs have no limits on acceptable risks (60%; p < .001).

Figure 3.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) responses on whether studies with different risk-benefit ratio would be allowed by the IRB if the study involves incapacitated adults.

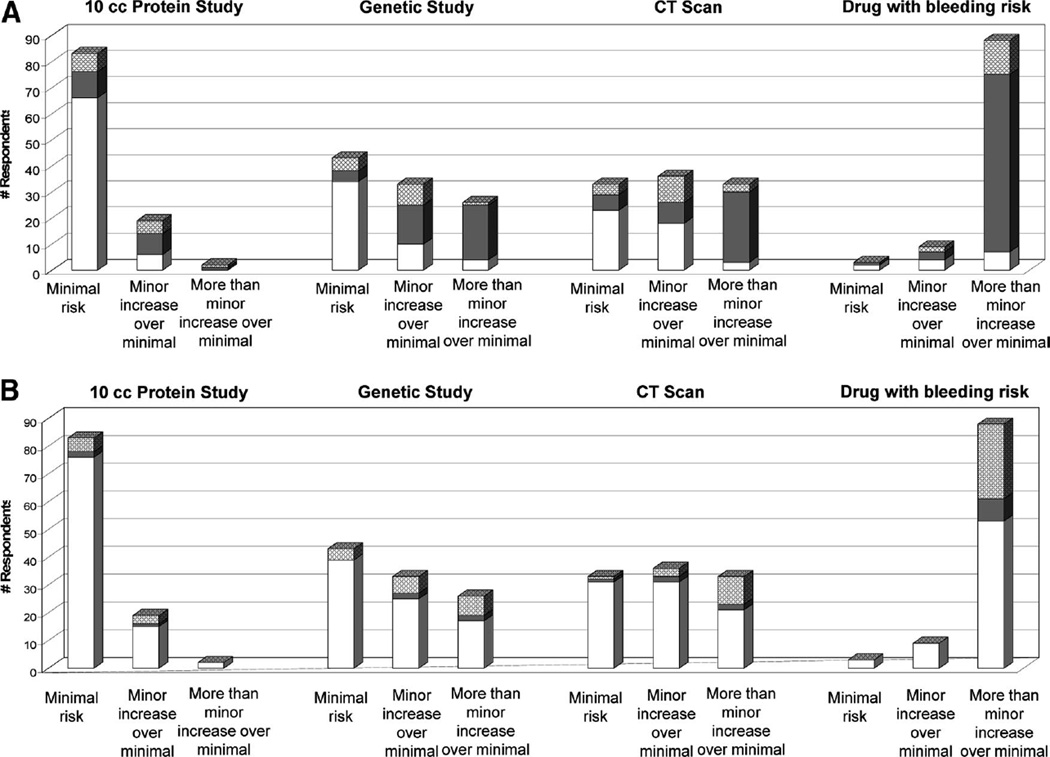

Because IRBs might have different interpretations of risk for study procedures, respondents were asked to categorize the risks of certain study procedures involving ICU patients. Most IRBs agreed that 10 mL of blood for protein analysis constitutes minimal risk (80%) whereas a drug with 3.5% chance of serious bleeding constitutes more than a minor increase over minimal risk (85%). But there is great variability in IRB responses to the genetic epidemiology study and the chest computed tomography study. The genetic study was considered by 39% of IRBs to be minimal risk, by 34% to be minor increase over minimal risk, and by 24% to be more than minor increase over minimal risk. Findings were similarly varied for the computed tomography scan study: 31% of IRB believed the computed tomography scan to be minimal risk, 35% considered it minor increase over minimal risk, and 32% considered it more than minor increase over minimal risk. Based on the IRB categorization of the risk of the genetic epidemiology and their responses on whether that level of risk was allowed, 40% of IRBs would not allow such studies to include incapacitated adults if there is no direct benefit (Fig. 4A). Fewer IRBs disallow such studies if there is potential direct benefit (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Respondents’ categorization of risk for study procedures and their responses as to whether this risk level is permitted in studies involving subjects who are incapacitated in studies without potential direct benefit (A) and with direct benefit (B). Institutional Review Board representatives were asked to categorize the risk of the following procedures: 10 mL blood for protein analysis study, 10 mL blood for genetic epidemiology study, one chest computed tomography (CT) scan, and administration of a drug with a 3% risk of severe bleeding. Each bar represents the number of respondents who categorize each study procedure as minimal risk, minor increase over minimal risk, or more than minor increase over minimal risk. Within each bar are their responses on whether their Institutional Review Board (IRB) would (white) or would not (gray) permit that risk level in studies involving incapacitated adults when there is no potential benefit (A) and when there is potential direct benefit (B). Cross-hatching indicates those who replied “unsure.” Two respondents were unable to categorize study risks for the gene study, CT scan, and drug study, resulting in two missing values.

Safeguards Used in Studies Involving Incapacitated Adults

IRBs were asked how often they require procedures to determine the ability to consent in studies involving different populations (Table 3). Many IRBs rarely or never require determination of the capacity of elderly research participants to consent (46%). Even in the ICU, where many patients are incapacitated, 21% of IRBs rarely or never require determination of consent capacity. The most common procedure used to determine capacity is asking subjects questions during the consent procedure (63% use this always or very frequently). Few IRBs use cognitive testing and independent monitors frequently or always (25% and 11%, respectively).

Table 3.

Frequency of certain IRB practices with research involving incapacitated adults

| Determination of Capacity to Consent to Research N (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Very Frequently |

Always | Unsure/Do Not Know |

|

| In your experience, how often would your IRB require procedures to determine ability to consent in studies involving: | ||||||

| Elderly | 18 (17%) | 30 (29%) | 33 (32%) | 13 (13%) | 7 (7%) | 3 (3%) |

| Dementia patients | 4 (4%) | 9 (9%) | 14 (13%) | 17 (16%) | 58 (56%) | 2 (2%) |

| Mental illness | 5 (5%) | 11 (11%) | 23 (22%) | 24 (23%) | 34 (33%) | 7 (7%) |

| Patients in the intensive care unit | 9 (9%) | 12 (12%) | 28 (27%) | 29 (28%) | 29 (28%) | 2 (2%) |

| Normal, healthy individuals | 65 (63%) | 22 (21%) | 7 (7%) | 2 (2%) | 8 (8%) | 0 |

| In your experience in the past year, how often were the following procedures used to determine the ability of potential subjects to consent to research? | ||||||

| Asking the treatment team about the subject’s ability to consent | 7 (7%) | 13 (13%) | 22 (21%) | 29 (28%) | 19 (18%) | 14 (13%) |

| Asking the subject questions to determine their understanding | 3 (3%) | 6 (6%) | 27 (26%) | 27 (26%) | 38 (37%) | 3 (3%) |

| Using a standardized validated test of cognitive function | 11 (11%) | 25 (24%) | 41 (39%) | 19 (18%) | 6 (6%) | 2 (2%) |

| Assessment by an independent third party not involved with the subject or investigative team | 14 (13%) | 41 (39%) | 31 (30%) | 9 (9%) | 2 (2%) | 7 (7%) |

| Procedures to protect incapacitated subjects in studies,a N (%) | ||||||

| In research requiring consent that will involve incapacitated adult patients, how often would your IRB require the investigator to indicate the scientific justification for including incapacitated adults in the study? | 1 (1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 93 (95%) | 0 |

| In such studies, how often would your IRB ask for evidence of the patient’s previous preference for research? | 27 (28%) | 19 (19%) | 16 (16%) | 9 (9%) | 8 (8%) | 19 (19%) |

| In such studies, how often would your IRB ask for assent or dissent from patient? | 5 (5%) | 8 (8%) | 16 (16%) | 20 (20%) | 41 (42%) | 8 (8%) |

| In studies involving incapacitated adult patients who require consent, how often would your IRB ask an independent monitor to provide assurance that research participation is consistent with the patient’s interest? | 14 (14%) | 36 (37%) | 28 (29%) | 7 (7%) | 5 (5%) | 8 (8%) |

| In the event that surrogate’s permission for research was accepted and an incapacitated research subject improves, how often would your IRB ask the investigator to consent the patient once decision making capacity returns? | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 6 (6%) | 12 (12%) | 68 (69%) | 6 (6%) |

| Frequency with which procedures are used with patients who are initially competent but who are likely to lose capacity to make decisions during the course of the study,a N (%) | ||||||

| In your best judgment of these situations, how often would your IRB ask the investigators to obtain permission from the patient at the beginning of the study when they are competent to continue in the study if they were to lose their decision-making capacity in the future? | 11 (11%) | 10 (10%) | 11 (11%) | 9 (9%) | 42 (40%) | 21 (20%) |

| In your best judgment, how often would your IRB ask the patient to designate a research surrogate or equivalent to make future research decisions for them in the event that they become incapacitated? | 12 (12%) | 10 (10%) | 19 (18%) | 18 (17%) | 28 (27%) | 17 (16%) |

| In your best judgment, how often would your IRB ask for patients to have an advanced directive or an equivalent on research in the event that they become incapacitated? | 25 (24%) | 22 (21%) | 12 (12%) | 14 (13%) | 11 (11%) | 20 (19%) |

IRB, Institutional Review Board.

Limited to the 98 respondents whose institutions allow surrogate consent for research involving incapacitated adults.

Among the 98 IRBs that do accept surrogate consent for research, most always or very frequently require investigators to justify the inclusion of incapacitated individuals (97%) and to ask for assent or dissent from the subject (62%). In the ICU, a patient may be incapacitated temporarily and 81% of IRBs do ask investigators to reconsent the subject if decision-making capacity returns. IRBs rarely or never ask for evidence of a subject’s previous preference for research (47%) or an independent monitor (51%).

In studies of progressive disorders in which the subject may lose capacity for decision making during the course of the study, such as dementia, 49% of IRBs would very frequently or always obtain permission from the patient to continue in the study if they lose capacity. Other procedures such as the assignment of a research surrogate and the development of an advance directive for research are used variably.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found tremendous variability in IRB practices with regard to surrogate consent and other safeguards to guide research involving incapacitated adults. Local review is an important aspect of IRB function. However, this wide variability suggests a need to define the “common practice” to help set the standards by which local IRBs can judge the adequacy or stringency of their existing practices, to inform the debate when there may be areas of controversy or disagreement, and to guide IRBs in the development of future policies.

Our evaluation of the scope of current IRB practices highlights major areas in the IRB approach on research involving incapacitated adults that should be reconsidered. In our study, 6% of IRBs surveyed would not accept surrogate consent for research, whereas many others limit who may serve as acceptable surrogate, often excluding adult children. These IRB practices do not reflect the views of patients. In previous studies, 68% to 96% of individuals reported that they would want society to accept surrogate consent for research in the event that they were unable to make decisions (28–31). Up to 72% of married and 96% of unmarried elderly individuals prefer their adult children to be their surrogates (17). All IRBs should accept surrogate consent for research involving incapacitated adults and, in the absence of a health care proxy, family including adult children should be accepted as surrogates for the patient.

The Common Rule allows for informed consent for research from the subject or the subject’s surrogate but relegates the definition of surrogate to applicable state laws (13, 32). Few states have laws on surrogate decision making for research. Most have laws on surrogate decision making for medical treatment, although many are limited to certain types of decisions relevant to life-sustaining procedures or to special populations such as patients with terminal illnesses or permanent coma (24). IRBs may not think that these laws can be extrapolated to research decision making. The presence of state surrogacy laws did not increase IRB acceptance of surrogate consent for research or acceptance of adult children as surrogates. Federal clarification of this issue will be needed before IRBs consistently accept surrogate consent for research. The Common Rule should be clarified to indicate that research involving incapacitated adults can occur after obtaining informed consent from the patient’s surrogate, and it should define the hierarchy of acceptable surrogates to include health care proxies, spouses, adult children, and other involved family members. The Subcommittee for the Inclusion of Individuals with Impaired Decision-Making in Research also called for similar clarification. Additionally, this subcommittee called for the Department of Health and Human Services to promote the passage of state laws to enable surrogate consent for research and to clarify how state laws on surrogate decision making for medical treatment may be extended to research (33). But, as the results from California IRBs in this survey suggest, the adoption of laws on surrogate decision-making for research may not be enough. Action at the local IRB level is needed to facilitate the acceptance of surrogate consent for research. In addition, any clarification of federal regulations should be published in leading journals in the areas of neurology, critical care medicine, psychiatry, and geriatrics with a commentary discussing possible implications for clinical studies in their field. This will inform the investigators rapidly and allow for more constructive dialog between IRB members and the scientific community on how to apply the federal regulations to ensure adequate protection for this vulnerable population.

The variability of surrogate consent practices is only one potential limitation to research involving incapacitated individuals. Our survey found additional IRB limitation based on whether the study confers potential benefit to the subject. In our study, 14% of surveyed IRBs would not allow any risk in studies without direct benefit. Additionally, 39% of IRBs would cap the allowable risk at the minimal level in studies without direct benefit. This cap on research risks in incapacitated adults is more restrictive than what is considered acceptable in pediatric research. The Common Rule allows for pediatric clinical research with minor increase over minimal risk and no direct benefit if it is “likely to yield generalizeable knowledge” or “a reasonable opportunity to further the understanding, prevention, or alleviation of a serious problem affecting the health and welfare of children” (34). It is difficult to see why cognitively impaired adults should be seen as more vulnerable than children and in need of greater restrictions on allowable risk-to-benefit ratios, especially when the condition being studied contributed to the cognitive impairment. Although IRB assessment of research risks and benefits is a legitimate and common safeguard used to protect research subjects, the NIH, the National Human Research Protections Advisory Committee, the National Bioethics Advisory Commission, and the Subcommittee for the Inclusion of Individuals with Impaired Decision-Making in Research agree that incapacitated adults can be adequately protected without placing a risk ceiling on research without direct benefit (19, 33, 35, 36). IRBs should allow minimal risk and minor increase over minimal risk research to involve incapacitated adults, even without benefit. As in the case of pediatric research, IRBs should weigh research risks in critical care studies in the context of the knowledge gained. Because the acute illness likely contributed to the cognitive impairment seen in the ICU, no understanding about critical illnesses can be gained without including incapacitated patients in research. For studies with more than minor increase over minimal risks and no direct benefit, there should be a greater burden on the investigator to demonstrate that any knowledge gained will reasonably lead to a better understanding of how to prevent or treat critically ill patients. Additional safeguards may also be required.

However, our study showed that many of the safeguards recommended by the NIH, the National Bioethics Advisory Commission, and other national, state, and international bodies are variably to rarely used by the IRBs. Implementation may be limited by practical challenges such as the difficulty in obtaining advance research directives (28). Additionally, there may be concerns about the impact of these safeguards on the feasibility of clinical studies on severe conditions. More than 50% of experienced dementia researchers believe that independent monitors would make dementia studies much less feasible or not feasible while providing only slight to no increase in additional protection for incapacitated patients (37). Other procedures such as obtaining assent or dissent and reconsent of patients are more practical and are not thought to impede the feasibility of research on the cognitively impaired. A reasonable approach is for IRBs to adopt safeguards such as regular screening for the capacity for consent and obtaining assent or dissent and reconsent as frequently as possible. However, studies with more than a minor increase over minimal risk and no potential benefit would require additional safeguards such as independent monitors and an advanced research directive, even if they may be more difficult to implement. The Subcommittee for the Inclusion of Individuals with Impaired Decision-Making in Research reasonably suggests that more stringent evaluation of the appropriateness of the surrogate and their decision-making process may be warranted in riskier research without potential direct benefit.

The limits on research risks revealed by this study may severely restrict and bias needed research in critical illnesses as well as other conditions that can affect a patient’s decision-making capacity. In a multicenter study investigating the genetic risk for acute strokes, investigators preferentially enrolled less severely affected, cognitively intact patients because the IRBs at 40% of the sites did not allow the use of surrogate consent to enroll incapacitated patients (38). The exclusion of severely sick patients will result in selection bias. Any knowledge gained from the research will be less applicable to those with more severe disease who may be most in need of scientific advancement.

Obviously, a key factor will be the IRB assessment of research risk in studies of incapacitated adults. However, the assessment of risk and benefit is an unclear area in IRB practice, with little guidance from current regulations. Similar to previous reports (39, 40), we found great variability in how IRBs assess risks in research. Greater involvement of the critical care community in the IRB process will be important to familiarize IRB members with the special risks and concerns of the critical care community.

Central IRBs were developed by National Cancer Institute to review multicenter phase III cancer trials to allow for IRB reviews on the national level, followed by a facilitated review on the local level (41). A central specialized IRB is most appropriate for large multicenter ICU studies, but much critical care research is conducted at a single institution and will need to be reviewed locally. In addition, the issue of research consent in decisionally impaired adults reaches far beyond the critically ill. Many hospitalized elderly patients, patients from chronic care facilities, and nonhospitalized patients with neurologic and psychiatric conditions may be decisionally impaired. It is unrealistic to expect that all studies that may involve incapacitated adults will be reviewed by special boards. All IRBs should have a common understanding of practices surrounding surrogate consent in research and the safeguards used in research involving incapacitated individuals. It is hoped that this study will help toward that goal.

There are several limitations to this study. We decided to survey U.S. institutions only because other countries are guided by different regulations. As is true of any survey, IRB responses may not reflect their actual practices or the practices across the institution. Particularly in large institutions, there may be differences in approach and perception between IRB chairs and different boards. However, our analyses of available IRB protocols found little disagreement between the IRB responses and their guidelines, suggesting that the responses do reflect the standard practices of the IRBs. It was beyond the scope of this study to examine specific research protocols evaluated by the participating IRBs. Thus, some variability in the response may reflect differences in the types of studies reviewed. But this is less likely for questions on general IRB practices such as acceptance of surrogate consent for research and who may serve as surrogates. Last, we chose to focus on surrogate consent for research because this is the most common procedure used in research involving decisionally impaired adults. We did not inquire fully about research conducted with a waiver of informed consent or exception from informed consent (42–44). Such research involving incapacitated adults may still occur in institutions that do not accept surrogate consent for research. But these special consent procedures are limited to minimal-risk studies that cannot be performed without a waiver or to the very narrow field of emergency resuscitative research under the Final Rule.

CONCLUSION

This constitutes the first study, to our knowledge, that directly surveys IRBs regarding their practices with regard to surrogate consent for research involving incapacitated patients. Although the majority of IRBs accepted surrogate consent, there was much variability in who may serve as acceptable surrogates, the level of allowable risk in studies without direct benefit, and the use of various practices to safeguard incapacitated adults in research. Such variability may have adverse consequences for needed research involving incapacitated adults.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the hard work and dedication of our research staff, Jaime Glick, Nadine Spring, Jeidy Carrasco, Adam Wright, Daniel Ceusters, John Frederick, MD, and the support of David Adams, MD, Corey Scurlock, MD, the cardiothoracic surgeons, critical care physicians, and nurses at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Supported, in part, by NHLBI HL084060 and HL086667. Dr. Gong received a grant from the National Institutes of Health. She had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.ccmjournal.com).

The remaining authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Protection of human subjects: Belmont Report–Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Fed Regist. 1979;44:23192–23197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:248–253. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer BW, Dunn LB, Appelbaum PS, et al. Assessment of capacity to consent to research among older persons with schizophrenia, Alzheimer disease, or diabetes mellitus: Comparison of a 3-item questionnaire with a comprehensive standardized capacity instrument. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:726–733. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkman CS, Leipzig RM, Greenberg SA, et al. Methodologic issues in conducting research on hospitalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:172–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smithline HA, Mader TJ, Crenshaw BJ. Do patients with acute medical conditions have the capacity to give informed consent for emergency medicine research? Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:776–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickey A, Clinch D, Groarke EP. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in the hospitalized elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:27–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199701)12:1<27::aid-gps446>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black BS, Brandt J, Rabins PV, et al. Predictors of providing informed consent or assent for research participation in assisted living residents. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:83–91. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318157cabd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisani MA, McNicoll L, Inouye SK. Cognitive impairment in the intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:727–737. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(03)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson TN, Raeburn CD, Tran ZV, et al. Postoperative delirium in the elderly: Risk factors and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2009;249:173–178. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, et al. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet. 1998;351:857–861. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raymont V, Bingley W, Buchanan A, et al. Prevalence of mental incapacity in medical inpatients and associated risk factors: Cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2004;364:1421–1427. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer disease in the US population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Federal policy for the protection of human subjects: Notices and rules. CFR 46.116. 1991;56:28016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federal policy for protection of human subjects. Part 46. Title 45. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1991. Subpart D. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SY, Appelbaum PS, Jeste DV, et al. Proxy and surrogate consent in geriatric neuropsychiatric research: update and recommendations. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:797–806. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan TS, Jatoi A. An update on advance directives in the medical record: Findings from 1186 consecutive patients with unresectable exocrine pancreas cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2008;39:100–103. doi: 10.1007/s12029-008-9041-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopp FP. Preferences for surrogate decision makers, informal communication, and advance directives among community-dwelling elders: Results from a national study. Gerontologist. 2000;40:449–457. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraham E, Matthay MA, Dinarello CA, et al. Consensus conference definitions for sepsis, septic shock, acute lung injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome: Time for a reevaluation. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:232–235. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200001000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wendler D, Prasad K. Core safeguards for clinical research with adults who are unable to consent. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:514–523. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-7-200110020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health and Human Services Office for the Human Research Protections Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections (SACHRP): subcommittees. [Accessed March 26, 2010]; Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp/subcommittees.html.

- 21.National Human Research Protections Advisory Committee: Clarifying specific portion of 45 CFR subpart D that governs children’s research. [Accessed June 14, 2010]; Available at: http://ctep.info.nih.gov/investigatorResources/childhood_cancer/docs/nhrpac16.pdf.

- 22.Luce JM. Informed consent for clinical research involving patients with chest disease in the United States. Chest. 2009;135:1061–1068. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah S, Whittle A, Wilfond B, et al. How do institutional review boards apply the federal risk and benefit standards for pediatric research? JAMA. 2004;291:476–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Default Surrogate Consent Statutes American Bar Association Comission on Law and Aging. [Accessed March 31, 2010]; [Accessed August 24, 2010]; Available at: http://new.abanet.org/aging/PublicDocuments/Famcon%20Chart%20-%20Final%202009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn NA, Blumenthal J. Designating health care decision makers for patients without advanced directives: A psychological critique. Georgia Law Rev. 2008;42:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luce JM. California’s new law allowing surrogate consent for clinical research involving subjects with impaired decision-making capacity. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1024–1025. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1745-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tansey B. University of California San Francisco violated patients’ rights: Doctors improperly got consent for study, feds say. San Francisco Chronicle. 2002 Jul 28; Sect A1. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wendler D, Martinez RA, Fairclough D, et al. Views of potential subjects toward proposed regulations for clinical research with adults unable to consent. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:585–591. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlawish J, Rubright J, Casarett D, et al. Older adults’ attitudes toward enrollment of non-competent subjects participating in Alzheimer’s research. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:182–188. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SY, Kim HM, McCallum C, et al. What do people at risk for Alzheimer disease think about surrogate consent for research? Neurology. 2005;65:1395–1401. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183144.61428.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SY, Kim HM, Langa KM, et al. Surrogate consent for dementia research: A national survey of older Americans. Neurology. 2009;72:149–155. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339039.18931.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Federal policy for the protection of human subjects: notices and rules. CFR 46.102(c) 1991;56:28013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections: Recommendations from the Subcommittee for the Inclusion of Individuals with Impaired Decision-Making in Research (SIIIDR) [cited June 15, 2010]; [Accessed August 24, 2010];2009 Available at: http://www.dhhs.gov/ohrp/sachrp/documents/20090715LetterAttach.pdf.

- 34.US Department of Health and Human Services. Federal policy for protection of human subjects. 1991;Title 45(Part 46) 406. [Google Scholar]

- 35.European Parliament and Council of European Unions. [cited March 12, 2009]; [Accessed August 24, 2010]; Available at: http://www.wctn.org.uk/downloads/EU_Directive/Directive.pdf.

- 36.National Human Research Protections Advisory Committee: Report from NHRPAC on Informed Consent and the Decisionally Impaired. [cited April 1, 2009]; [Accessed August 24, 2010];2002 Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/nhrpac/documents/nhrpac10.pdf.

- 37.Stocking CB, Hougham GW, Baron AR, et al. Are the rules for research with subjects with dementia changing? Views from the field. Neurology. 2003;61:1649–1651. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098888.97357.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen DT, Meschia JF, Brott TG, et al. Stroke genetic research and adults with impaired decision-making capacity: A survey of IRB and investigator practices. Stroke. 2008;39:2732–2735. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janofsky J, Starfield B. Assessment of risk in research on children. J Pediatr. 1981;98:842–846. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80865-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Luijn HE, Musschenga AW, Keus RB, et al. Assessment of the risk/benefit ratio of phase II cancer clinical trials by Institutional Review Board (IRB) members. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1307–1313. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christian MC, Goldberg JL, Killen J, et al. A central institutional review board for multi-institutional trials. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1405–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205023461814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laffey JG, Honan D, Hopkins N, et al. Hypercapnic acidosis attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:46–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-394OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Protection of human subjects; informed consent–FDA. Final rule. Fed Regist. 1996;61:51498–51533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.