Abstract

A central goal of systems biology is to elucidate the structural and functional architecture of the cell. To this end, large and complex networks of molecular interactions are being rapidly generated for humans and model organisms. A recent focus of bioinformatics research has been to integrate these networks with each other and with diverse molecular profiles to identify sets of molecules and interactions that participate in a common biological function— i.e. ‘modules’. Here, we classify such integrative approaches into four broad categories, describe their bioinformatic principles and review their applications.

Introduction

Cellular organization is thought to be fundamentally modular1,2. At the molecular level, modules have been variously described as groups of genes, gene products, or metabolites that are functionally coordinated, physically interacting and/or co-regulated1-7. For example, a pioneering perspective1 on modular cell biology described a module as a distinct group of interacting molecules driving a common biological process— for example., the ribosome is a module that synthesizes proteins. Modules, in essence, are functional building blocks of the cell1-7.

In an effort to develop a complete map of biological modules underlying cellular architecture and function, large networks of inter-molecular interactions are being measured systematically for humans and many model species8-16. Such networks include physical associations underlying protein-protein, protein-DNA or metabolic pathways, as well as functional associations, including epistatic and synthetic lethal relationships between genes, correlated expression between genes, or correlated biochemical activities among other types of molecules (Supplementary Table 1). Numerous approaches have been advanced to mine such networks for identifying biological modules, including methods for clustering interactions and those based on topological features of the network such as degree and betweenness centrality (as reviewed5-7; see glossary). These approaches are based on the premise that modular structures such as protein complexes, signaling cascades, or transcriptional regulatory circuits display characteristic patterns of interaction5-7.

Module discovery in biological networks has been extremely powerful for elucidating molecular machineries underlying physiological and disease phenotypes5-7,17-19. Nonetheless, many challenges confound the interpretation of biological networks and their embedded modular structures. A first challenge relates to the sheer complexity of the problem at hand-it is not yet completely clear how to transform data for thousands of molecular interactions into functionally coherent models of cellular machinery. Second, technological biases in high-throughput approaches20-22 can compromise signal accuracy. For example, experimental artifacts, variability in coverage across datasets, sampling bias towards well-studied processes, limitations in screening power and inherent sensitivities in various assays can yield false positives and false negatives in interaction data23-26. Third, individual high-throughput experiments measuring a subset or type of interactions (e.g., protein-protein or protein-DNA), simply cannot expose the full interaction landscape of a cell. Finally, as molecular networks are commonly assembled in single, static experimental conditions, they grossly overlook the inherently dynamic nature of molecular interactions, which can be massively rewired during physiological or environmental shifts10,27,28. Hence, current network models reveal only partial and static snapshots of the cell.

A key strategy to address these challenges is data integration. In recent years, a rich collection of integrative methods has emerged for identification of network modules of high quality, broad coverage, and context-specific dynamics. Here, we review these integrative approaches, highlighting their logical underpinnings and biological applications. We classify integrative module discovery methods into four broad categories: identification of ‘active modules’ through integration of networks and molecular profiles, identification of ‘conserved modules’ across multiple species, identification of ‘differential modules’ across different conditions, and identification of ‘composite modules’ through integration of different interaction types. Together, these four categories encompass a wide spectrum of network integration strategies and available data types. An illustrative poster29 titled ‘Integrative Systems Biology’ was previously published and is recommended as an accompanying guide.

Identification of ‘active modules’

One of the most successful integrative approaches has been to overlay networks with molecular profiles to identify ‘active modules’. Molecular profiles of transcriptomic, genomic, proteomic, epigenomic and other cellular information are rapidly populating public databases (Supplementary Table 1). As these profiles capture dynamic and process-specific information correlated with cellular or disease states, they naturally complement interaction data, which are primarily derived under a single experimental condition. Computational integration of network and ‘omics’ profiles has thus become a popular strategy for extracting context-dependent active modules, which mark regions of the network showing striking changes in molecular activity (e.g., transcriptomic expression) or phenotypic signatures (e.g., mutational abundance) associated with a given cellular response4,30-38 (Figure 1; these regions have alternatively been described as network hotspots39,40 or responsive subnetworks41-43).

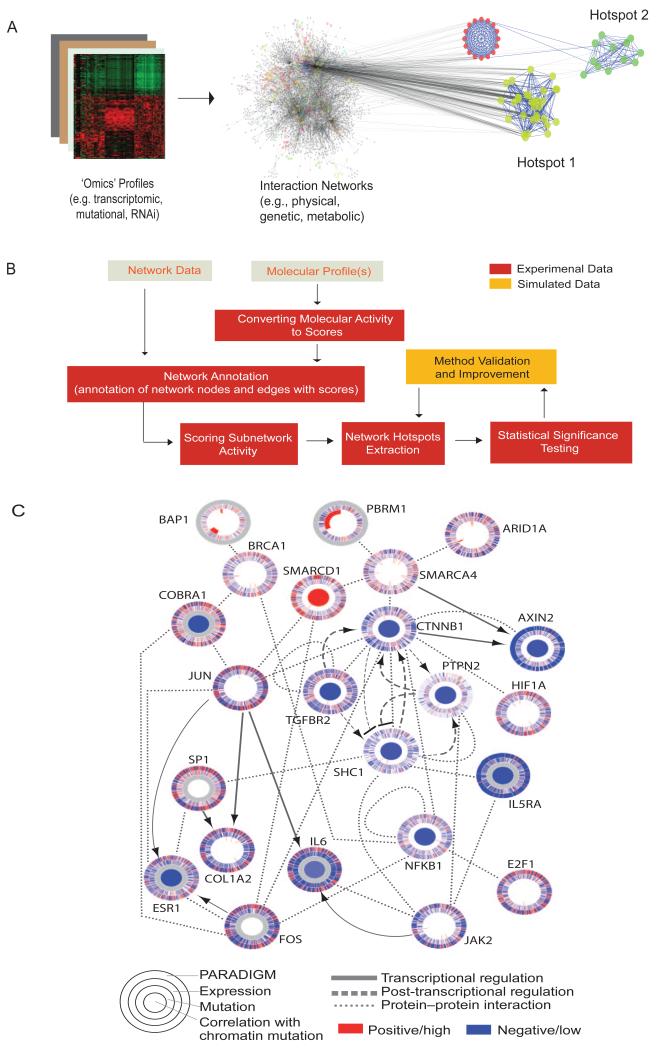

Figure 1. Identifying ‘network hotspots’.

(A) Schematic representation of active modules inferred through integration of biological networks and cellular state profiles. (B) Common procedural workflow involved in active module identification. Panel C shows regulatory interactions of clear renal cell carcinoma cancer genes70 that were identified by integrating mutation, copy number and mRNA expression data, with pathway information catalogued in public databases using the PARADIGM algorithm. In particular the network identified roles for chromatin remodelers in this cancer. Each gene is depicted as a set of concentric rings representing various levels of biological information, and where each ‘spoke’ in a ring pertains to a single patient sample. From periphery inwards, the rings indicate ‘PARADIGM’-inferred levels of gene activity, mRNA expression levels, mutational abundance and correlation of gene expression or activity to mutation events. Reproduced with permission from Nature 2013.

A large number of computational techniques have been developed that automate large-scale identification of active modules in an unbiased manner. Several of these methods have been packaged as publicly-available application tools (Table 1). These methods generally fall into three classes, as follows. Given the rapid emergence of integrative methodologies, some effort has been made to compare their accuracy (precision), sensitivity (recall) or computational efficiency within individual method classes44-46. However, unbiased comparisons across different methods’ classes using uniform data metrics will need to be undertaken comprehensively47.

Table 1. Some recent bioinformatics tools for module extraction through network integration.

Significant-area-search methods

The first class of methods, themed SigArSearch (Significant-Area-Search)31,33,48 was previously reviewed43. Many of these methods33,41,44,48-56 descend from an early formulation, JActiveModules48, (also implemented as an application tool through the network analysis/visualization platform, Cytoscape57; Table 1), which was the first to frame the active modules search task as an optimization problem. SigArSearch methods invoke three common procedural steps for module discovery (Figure 1). First, network nodes (molecules), and/or edges (interactions) are annotated with scores quantifying molecular activity, where activity is measured via molecular profiles such as gene expression levels- the most common data choice in such applications. Next, a scoring function is formulated to compute an aggregate score for each subnetwork, reflecting overall activity of member nodes/interactions. Subsequently, a search strategy is devised to identify subnetworks with high scores, which mark active modules.

Scoring and search of active modules present a range of computational considerations and implementations43. Different scoring functions have assumed scores on network nodes48, or edges41,58 or both59; or constrained scores by topology56 or signal content44; or prioritized by high-scoring ‘seed’ nodes60, including using strategies for computational color coding of ‘seed’ paths51,55. Active module search has proven to be a computationally difficult problem48. Hence, so-called heuristic solutions (e.g. based on greedy52,61-63, simulated annealing48 or genetic64 algorithms; Box 1) that optimize computing time by recovering high-scoring subnetworks without necessarily seeking the maximally-scoring (globally optimal) subnetworks have been widely applied. Nevertheless, exact methods that guarantee the detection of maximally scoring subnetworks, albeit at higher computational expense, have been programmed to run in fast time-scales44,45,65,66.

Box 1: Common bioinformatics themes applied in integrative module-finding approaches.

Simulated Annealing (SA) A probabilistic heuristic that attempts global optimization of a function in a large search space (analogous to a physical system) and aims to bring the system from an arbitrary initial state to an optimized state using minimum energy. SA was the first heuristic to be applied for hotspots searching. In one SA framework48, sub-networks were expanded through iterative addition of active nodes (showing significant molecular activity) until no further gain in sub-network score was possible. A node was randomly selected per iteration Ti and its state toggled between active or inactive. The toggle was retained if sub-network score increased as a result of the addition, or else, accepted according to the probability function where η reflects the score of the highest-ranking component of a sub-network at a given iteration i.

Greedy methods Greedy algorithms create decisions that locally optimize an iterative step. For example, in one greedy-based scheme52, sub-networks were iteratively expanded from high-degree nodes until (i) aggregate sub-network score fell below a predefined threshold, or (ii) sub-network size was saturated. Alternately, nodes only within a fixed radius of the seed node were aggregated62. In a greedy variant of SA, the number of negative scoring nodes admitted per iteration (inactive) was limited61.

Genetic Algorithms (GA) GA mimic natural selection among members of a population to iteratively compute various combinations of solutions, selecting those with the best fitness (scores). In one GA-based hotspot detection method64, node fitness was estimated based on both, molecular activity and network topology.

Exact Approaches- Exact methods extract maximally scoring as well as highly scoring sub-networks in optimum timeframes44,45,65,66. One such method44 allowed fast recovery of modules by transforming the sub-network search task into a well-known prize-collecting Steiner trees (PCST) problem and solving it using integer linear programming (ILP).

Network propagation (network smoothing) NP methods propagate network flow from select nodes to identify sub-networks accumulating the maximum ‘flow’ (or influence from neighboring nodes). In one such method67, an ‘influence graph’ was generated by releasing flow from cancer genes (source node) along interaction edges, where weight (w) of an edge between a pair of nodes gi and gk was given by the relationship w(g↓i, g↓k) = min(influence (g↓i, g↓k), influence (g↓k, g↓i)). To identify cancer hotspots, the influence graph was decomposed into sub-graphs of connected maximum coverage which tends to be a polynomial-hard problem. An alternate model of ‘enhanced influence’ was devised to reduce this complexity through enhancing the measure of network connectivity (influence) by multiplying edge weights (w) with the number of mutations associated per interacting gene pair.

Co-clustering methods These methods allow simultaneous clustering of interaction data and conditional profiles to identify co-regulated or correlated modules. In a bi-clustering method, cMonkey69, p-values of correlated expression (rik), sequence similarity (sik) and network connectivity (qik) were measured and aggregate p-value was defined as joint membership probability (πik). Using SA, nodes with high membership values πik≈1 were iteratively aggregated; those with low values πik ≈0 were dropped; while those with intermediate values were added with decreasing probability per iteration (heat gradient) to identify hotspots.

Diffusion-flow and network-propagation methods

The second group of methods for active module identification emulates the related concepts of diffusion flow and network propagation36,37,45,67-72. Analogous to fluid or heat flow through a system of pipes, network ‘flow’ is ‘diffused’ from nodes implicated in molecular profiles, such as differentially-expressed or known disease genes. The flow reaches outwards along network edges to subsequently identify active modules as subnetworks accumulating maximum flow.

Recently, a series of bioinformatics tools including HotNet67, PARADIGM70, MEMo73 and Multi-Dendrix37 (Table 1) have incorporated propagation-based methods for network mapping of cancer mutations. These methods have proven particularly valuable for discovering mutational hotspots in human cancers67,70-74, and additionally discriminating ‘driver’ oncogenic pathways from ‘passenger’ mutations37 For example, in one implementation of the application tool HotNet67, significantly mutated pathways in glioblastomas and adenocarcinomas were identified through network-propagation of associated cancer mutation profiles. Here, diffusion flow was run on a human protein-protein network seeded from known cancer genes to map their global neighborhood of interaction. This operation translates to computing the net ‘influence’ of cancer genes on all remaining genes in the network (Box 1). The resulting ‘influence network’ (representing the full set of network connectivities surrounding cancer seed genes) was subsequently partitioned into weighted subnetworks, thresholded either by number of patients in which they were mutated, or by average number of somatic mutations associated per interacting gene pair in a given subnetwork, as informed by tumor sequence profiles. The highest weighted sub-networks marked significantly mutated cancer pathways. Such strategies have become increasingly popular and data-rich due to easy availability of genome sequence and other ‘omics profiles in public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas75 (TCGA; http://cancergenome.nih.gov/).

Additionally, a number of propagation-based tools such as RegMod45, ResponseNet76 and NetWalker77 (Table 1) permit functional network analysis informed by transcriptomic data. For example, a network-optimization framework dubbed ResponseNet traces information flow from upstream response regulators through signaling and regulatory pathways embedded in integrated protein networks for providing pathway-based explanations for downstream transcriptional changes captured in gene expression profiles.

Network propagation methods are particularly suitable for annotation, ranking, or clustering of genes (such as disease genes) based on affiliations formed by network connectivity. In these situations, the precise architecture of a network may hold less concern. Rather, the primary motivation behind network propagation is to take advantage of the general functional proximity of genes to one another. Hence the phrase ‘network smoothing’ has come to describe such strategies.

Clustering-based methods

The third group of methods employs simultaneous clustering of network interactions and the conditions under which these interactions are active, in a concept termed ‘bi-clustering’46. Clustering based on network connectivity alone has proven instrumental in defining basic principles of modular network organization7,78,79. Bi-clustering algorithms further expand these capabilities by evaluating both network connectivity as well as the correlation of performance across multiple biological datasets36,46,80,81. A quantitative assessment of bi-clustering methods was recently presented46. Many (bi)clustering methods have been adapted as application tools (Table 1) such as SANDY82, SAMBA83 and cMonkey69 (Box 1), that permit multiplexed data analysis by interpreting global network topology and statistics in contexts of transcriptional regulatory information, differential expression profiles across multiple conditions and/or other biomedical evidences (phenotypic, sequence-based, literature, and/or clinical information).

Modules derived through such a broad spectrum of data, covering multiple levels of biological regulation, are providing increasingly comprehensive interpretation of biological systems. For example, methods have also been developed for identifying active modules within metabolic networks, in which omics or regulatory data are used to constrain the allowable metabolic fluxes through the reactions in the network. High-flux reactions (edges) are clustered together and reported as active modules. We refer the reader to recent reviews84,85 on integrative methods for modeling of metabolic networks through omics-based constraints. A version of the application tool, COBRA (constraint-based reconstruction and analysis; Table 1) permits omics-constrained analysis of genome-scale metabolic networks to predict feasible metabolic phenotypes and relevant modules under a given set of conditions86.

Applications of active modules

Active modules have been identified using a wide array of interaction types (e.g. protein-protein, regulatory and metabolic; Supplementary Table 1A) and ‘omics’ profiles (e.g., gene-expression, mutation status, RNAi phenotypes and other cellular state data; Supplementary Table 1b), any combination of which may be applied within a single module-finding application.

A great many applications have related to interpretation of omics profiles in context of protein-protein interaction networks34,39,48,50,62,67,70,72-74,81,87. For example, a recent study72 established a comprehensive network view of molecular pathways altered in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccCRC) by analyzing a diverse cohort of TCGA-derived omics data including gene-expression, genome mutation, and methylation profiles in conjunction with human protein-protein interactions. The methods HotNet and Paradigm were used to identify cancer-relevant active modules (Figure 1c), highlighting PI3K pathways and SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complexes. Moreover, aberrant remodeling of cellular metabolism was found to recurrently affect tumor stage and severity. Similarly, employing the application program ResponseNet, yeast networks of protein-protein, metabolic and protein-DNA interactions were analysed simultaneously with mRNA-profiling data to discover pathways responding to alpha-synuclein toxicity88.

Another study applied the JActiveModule method to detect protein-protein pathways showing dysregulated expression in human breast cancer62. Compared with individual cancer gene markers, these expression-based modules showed greater accuracy in distinguishing metastatic from non-metastatic breast cancers, demonstrating the superior power of module-based biomarkers for disease prognosis. Alternatively, co-clustering of RNAi data with protein-protein networks identified HCV-responsive modules in humans, establishing the role of human ESCRT-III complex as an infection-permissive host factor81. Other discoveries of omics-derived modules using protein interaction knowledge have spanned a variety of model organisms, including metabolism in yeast48, drug response in Mycobacterium tuberculosis50, aging in Drosophila89, aging56 and embyogeneisis in C. elegans34, and cellular responses to inflammation87, HIV infection61, or TNF-mediated stress90 in humans.

Another prominent group of applications relates to integration of omics profiles with protein-DNA interaction networks for identification of active regulatory pathways4,82,91. For example, co-clustering of protein-DNA interactions and multi-condition gene-expression profiles in yeast demonstrated widespread dynamic remodeling of transcription networks in response to diverse environmental stimuli82. It further showed that while a few transcriptional complexes act as constant “hubs” of transcription (see glossary), most appear transiently under particular conditions. In another study, differentially expressed arsenic responsive pathways were extracted through overlay of transcriptional profiles on yeast protein-DNA networks using the jActiveModule platform91. It was found that transcriptional data recognized important transcriptional complexes in regulatory networks but not in metabolic networks, while phenotypic profiles (of arsenic sensitivity) mapped more cohesively onto metabolic networks.

Active module finding has also been applied to metabolic networks50,91-93. Constrain-based methods for analyzing metabolic networks, including the widely exploited flux balance analysis (FBA) method, predict steady state distributions of metabolic fluxes based on various physio-chemical constrains such as rates of cellular growth and bioenergetics94. A recent variation on these methods adopts an integrative framework, whereby metabolic flux predictions are guided by omics or regulatory information (as reviewed84,85). For example, a genome-scale reconstruction of a human metabolic network (curated from literature evidences) was constrained using quantitative measures of gene- and protein- expression to predict tissue-specific metabolic uptake and release92. The study revealed a central role for post-transcriptional regulation in directing tissue-specific metabolic behaviors and associated metabolic diseases.

Discovery of active modules has paved the way for exciting diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. For example, active modules showing characteristic patterns of gene expression correlated with specific disease phenotypes can yield valuable biomarkers for disease classification62,95,96. Module-based biomarkers achieve greater predictive power and reproducibility over single gene markers, as demonstrated for the classification of numerous human disorders including Alzheimer’s97, diabetes36,98-100 and several forms of cancers including breast cancers45,55,62,99,101,102, ovarian cancer73,103,104, glioblastomas67,70,73,74, and others39,72,95,105,106. Because active modules can reveal pathway-centric insights reinforced by multiple lines of evidence, they naturally provide mechanistic explanations for complex traits and multi-genic diseases like cancer. Moreover, active modules can assist in discovery of drug-target pathways50,107 and predicting patient outcomes, such as response to chemotherapy55.

Identification of ‘conserved modules’

Biological networks undergo significant rewiring through evolutionary time, concomitant with gains, losses, or modifications in gene functions108-111. Therefore, network modules showing conservation over large evolutionary distances are likely to reflect well preserved ‘core’ functions maintained by natural selection. Discovery of such ‘conserved modules’ can address fundamental questions about biological regulation while predicting evolutionary principles shaping network architectures. Some publicly available tools for finding conserved modules are summarized in Table 1.

Conserved interactions

In one of the most fundamental approach to identifying conservation at the network level, individual interactions have been observed to occur between orthologous gene-pairs in two species, corresponding to conserved protein-protein (interologs)112 or conserved regulatory (regulogs)113 interactions. In one interesting extension of this idea, a network of co-expressed gene pairs in humans, flies, worms and yeasts was derived and, then a clustering algorithm used to extract conserved modules underlying cell cycle regulation and other core cellular processes3.

Beyond conservation of individual interactions, comparison of modules across species may reveal high overall consistency in structure and function despite lack of one-to-one correspondence at the level of individual molecules or interactions. Hence, a group of approaches have been developed to align complex network structures, paralleling advances in computational solutions for cross-species sequence comparison114. These network alignment approaches can be organized as follows:

Pairwise network alignments

Computational methods for network alignment have greatly advanced evolutionary comparisons of network modules. For example, local network alignment tools like PathBlast115 and NetworkBlast116 permit parallel comparisons of simple pathways (also known as linear paths) or subnetworks (also known as modules), respectively. These methods employ a common heuristic workflow whereby a merged representation of two networks, denoted the ‘network alignment graph’, is searched for conserved paths or subnetworks based on a probabilistic log-likelihood model of interaction densities.

Parallel alignment of multiple networks

Network alignment has been progressively scaled for analysis of multiple (more than two) networks. For instance, fast computation of conserved modules across as many as ten species was achieved in one study117 by redefining the alignment graph in NetworkBlast and treating multiple networks as separate layers linked via common orthology (see glossary). Orthology, as in the above methods, is commonly defined based on sequence homology. However, each gene/protein may potentially harbor multiple orthologs and paralogs due to gene duplication events in any of the multiple species being compared. The resulting many-to-many correspondences between putative orthologs can introduce high computational complexity in network alignment methods, which can scale exponentially with the addition of each new species and corresponding network. To address this scalability issue when aligning graphs from multiple species, global alignment methods such as those implemented in a recent study118 and network alignment tools such as IsoRank119 and Graemlin120 allow for functional orthologs based on similar neighborhood topologies across species (i.e., the overall arrangement of interactions surrounding a gene or protein or molecule).

Network alignment incorporating evolutionary dynamics

An important question in network evolution pertains to how evolutionary dynamics of genome modification shape network architecture over time121-123. Network alignment methods for scoring module conservation such as MaWish124 and others are increasingly incorporating evolutionary rates of gene deletion, insertion or/and duplication for accurate representation of the network evolution model. One study125 additionally accounted for the phylogenetic history of genes, through reconstruction of a conserved ancestral PPI network (CAPPI) from multiple species and its subsequent projection on the individual networks to identify conserved subnetworks across fly, worm and humans.

Applications of conserved modules

Conservation-based studies have provided fascinating insights into network evolution. For example, the identification of conserved metabolic genes and reactions across Archea, Bacteria and Eukaryotes, followed by species clustering and simulations in the presence and absence of oxygen, evidenced that the emergence of all three domains of Life predated widespread availability of atmospheric oxygen, and that adaptability to oxygen was coupled with increased network-complexity, and concurrently, increased biological complexity126.

Additionally, comparative analyses of conserved modules can supplement sequence-matching techniques for function prediction114,127-130, based on the premise that interaction partners of orthologous genes or proteins are likely to be functionally conserved as well. This was illustrated in the proof-of-principle application of NetworkBlast, where 4,645 previously uncharacterized protein functions were predicted based on their conserved interaction neighborhoods inferred based on pairwise alignment of protein-protein networks across yeast, worm, and fly116.

Evolutionary conservation can also support predictions of drug-action mechanisms: when a given drug is shown to target elements of a module that is conserved across two evolutionary distant model organisms, the probability that the same drug also targets the corresponding conserved module in humans increases131. Furthermore, identification of evolutionarily diverged modules in pathogenic species can uncover pathogen-specific drug targets that are absent in humans132.

‘Differential’ network modules

Molecular interactions can change dramatically in response to cellular cues, developmental stages, environmental stresses, pharmacological treatments and disease states32,101,130,133,134. Yet the inherently dynamic wiring of molecular networks remains under-explored at the systems level, as interaction data are typically measured under single conditions (e.g., standard laboratory growth media). Therefore, a number of so-called ‘differential’ network analyses (Figure 2) have adopted an experimental approach whereby biological networks are measured and compared across conditions to identify interactions and modules that are differentially present, absent or modified.

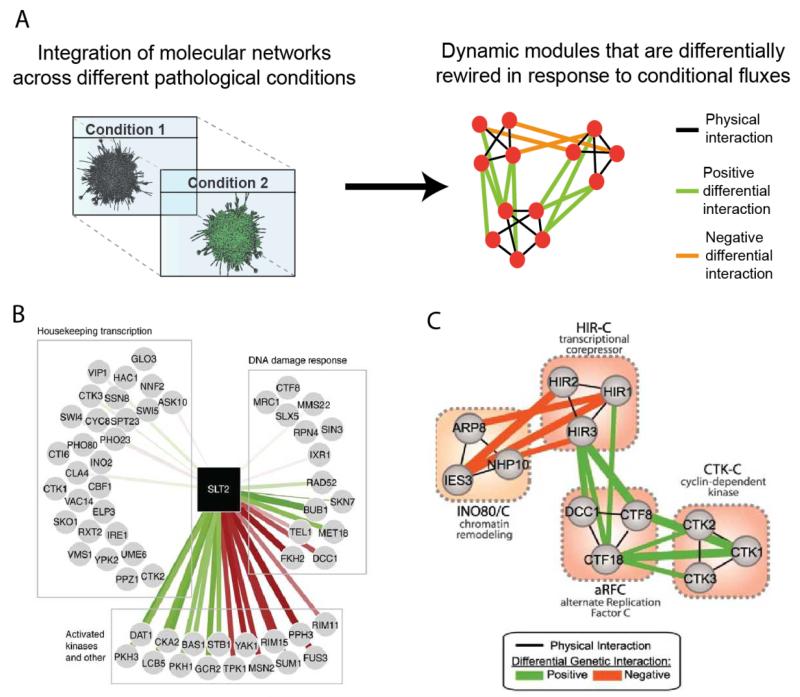

Figure 2. Differential analysis of molecular networks across conditions.

(A) Schematic representation of a differential mapping approach to identify dynamically rewired modules. Molecular networks are assembled under multiple static conditions and these static networks are subtracted across a pair of conditions to deduce differentially enriched interactions and modules. As illustrated, differential genetic modules may be further projected on protein-protein interactions to display functional (genetic) interrelations within and among protein complexes. (B) Differential rewiring of the Serine/threonine MAP kinase SLT2 protein-protein interactions before and after methyl methanesulfonate -induced DNA damage in yeast. Red and green edges indicate positive and negative differential interactions (i.e., corresponding pairwise-deletion phenotypes associated with these interactions are deemed favorable or detrimental for survival respectively). Adapted from Molecular systems biology (2012) (C) Differential genetic interactions can co-cluster between protein complexes (pathways). The network shows cross-pathway genetic interactions bridging distinct protein complexes (pathways) functioning in DNA damage response in S. cerevisiae27 Adapted from Science.

Principles of differential network analyses

Analogous to ‘differential’ expression analyses, differential network analysis involves pair-wise subtraction of interactions mapped in different experimental conditions130. The subtractive process filters out ubiquitous interactions (so-called ‘housekeeping’ interactions130) that are redundant to all static conditions of interest. By selectively extracting interactions relevant to the studied condition or phenotype, this reduces the typical complexity of static networks. Most notably, differential networks tap interaction spaces that are inaccessible to static networks, as individual interactions that may be too weak (in magnitude of interaction strength) to capture in either static condition can be solely identified based on significance of their differential measure27,130. Such differential interactions once identified, may be further organized into modules using a number of hierarchical or graph clustering methods47,135 or various Cytoscape57-based network analysis tools136,137.

Applications

Physical networks assembled from quantitative protein-DNA and protein-protein binding data under different conditions were some of the first to be analyzed in a differential mode. For example, utilizing standard ChIP-based assays for protein-DNA interactions in vivo (Supplementary Table 1), alterations in Transcription Factor-promoter binding following amino acid starvation10 or chemical induction of DNA-damage138 were mapped in yeast, providing insights into dynamic regulation of stress response pathways. Similar comparisons of protein–protein interactions following epidermal growth factor (EGF) treatment in yeast have shed light on EGF-dependent signaling139. A recent study140 exploring tissue-specific effects on network wiring demonstrated a profound role of tissue-regulated alternate splicing on dynamic remodeling of protein-protein networks. Using a luminescence-based mammalian interactome mapping approach (LUMIER) for measuring physical binding between experimentally chosen ‘bait’ (seed) and ‘prey’ (target) proteins, the authors mapped protein-protein interactions between normally functioning ‘prey’ proteins and several neurally-regulated ‘bait proteins’ that were genetically engineered to include or exclude specific exons with the purpose of exploring exon-dependent effects on network wiring in human cells. The study found that almost a third of neurally-regulated exons that were tested significantly modulated protein-protein interactions, and that overall, tissue-dependent exons participated in more protein-protein interactions than other proteins.

Differential analysis has also been performed across functional networks (i.e., as opposed to physical networks, see Supplementary Table 1). For instance, we applied an approach termed differential epistasis mapping (dE-MAP) to compare genetic networks induced by different types of DNA damaging agents27,141. In another example, gene co-expression networks from transcriptomic profiles of normal or prostate cancer samples were compared to identify subnetworks induced in prostate cancer142. Differential, but not static networks, in this study successfully recognized known prostate cancer-specific interactions for RAD50 and TRF2.

Similarly, metabolic networks assembled from correlated activities of liver metabolites were differentially compared between normal and diabetic conditions to identify functional regulators of diabetic dyslipidemias in humans143. It is likely that continued advances in differential network mapping and analysis will shed light on tissue-specific, spatio-temporal and dosage-dependent rewiring of biological networks.

Discovery of ‘composite functional’ modules

Rationale for composite modules

Different types of biological interactions provide distinct, yet complementary, insights into cellular structure and function. For instance, protein-protein, regulatory and metabolic networks each reflect a different aspect of the physical architecture of a cell (Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, ‘genetic’ interactions, which quantify epistatic effects of one gene on the phenotype expressed by another, reveal functional relationships between gene pairs. A key opportunity lies in reconciling these complementary network views of the cell into cohesive models. Powerful integrative approaches aimed at identifying composite functional modules composed of multiple types of biological interactions are providing considerable advances in this direction.

Modes and applications

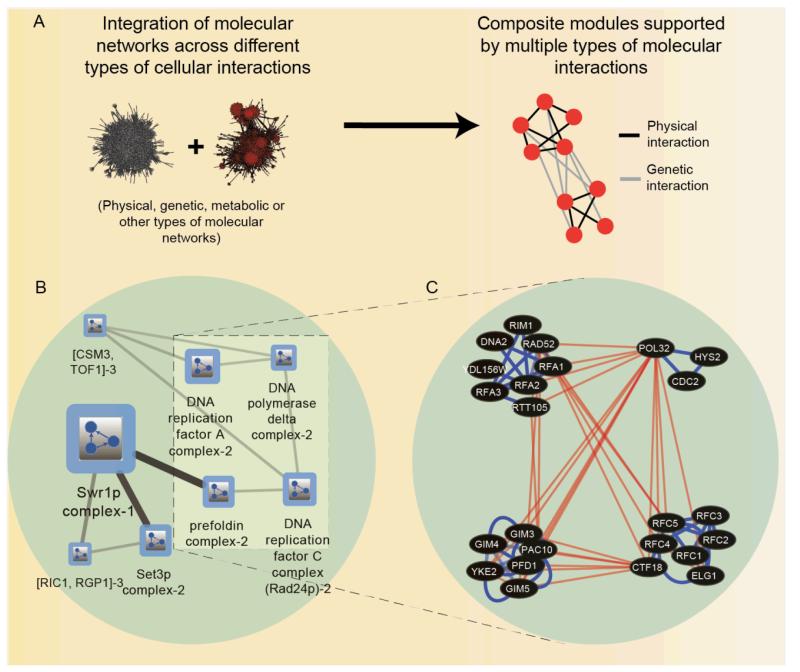

One class of approaches maps ‘composite modules’ that are jointly supported by physical and genetic interactions144 (Figure 3). A common theme in these approaches13,129,145-147, implemented in the application PanGia148 (Table 1), involves identification of overlapping clusters of physical and genetic interactions as ‘composite modules’ implicating genes acting ‘within’ a pathway. Clusters of genetic interactions bridging two different composite modules reflect inter-module dependencies running ‘between’ synergistic, compensatory or redundant pathways145. Integrative analysis of composite physical-genetic modules can reveal physical mechanisms underlying mutational phenotypes associated with genetic screens, or conversely, predict genetic dependencies between protein complexes mapped in physical binding assays. Module maps elucidating global physical-genetic interrelations have been assembled in a number of studies exploring Hsp90 signaling149, chromosomal biology13,146, RNA processing150, secretory pathways151, DNA damage response27, or global biological processes145,152.

Figure 3. Integrating networks across interaction types.

(A) Schematic view of composite functional modules identified through computational integration of genetic and physical networks. (B) A hierarchical module map extracted from network information obtained from ref 130 using the Cytoscape57 based application tool, Pangia148 illustrating intra-modular and inter-modular relationships in a joint network of protein-protein interactions and genetic interactions in yeast. Modules are determined based on physical and genetic interaction densities. Functional modules are represented as boxes, while edges between boxes represent the density of inter-module genetic interactions, i.e. connecting genes across the two modules (C) Magnified internal view of four network modules revealing their physical interactions and distinct ‘within-pathway’ and ‘between-pathway’ genetic interactions, where blue and red edges symbolize protein-protein and genetic interactions respectively. Networks were produced using data from 130 and the cytoscape tool.

Integrative strategies have similarly uncovered ‘composite modules’ in signaling and regulatory networks, primarily through combined evaluation of protein-DNA (transcription factor (TF)-target) and protein-protein interactions 11,59,153,154, or by additionally including genetic interactions152. In early work along these lines, composite ‘motifs’ comprised of regulatory and protein-protein interactions among 2, 3 or 4 proteins were mapped and classified into distinct feed-forward loops, interacting transcriptional hubs and other logical circuits153. Such simple ‘motifs’ were thought to combine with recurrent patterns to organize higher-order network ‘themes’ or complex functional modules associated with specific biological responses152. In other work along these lines154, yeast protein-protein and protein-DNA interaction networks were combined to identify 72 co-regulated protein complexes. Such coregulated complexes depict dense protein clusters (in protein-protein networks) whose members are jointly regulated by a common set of transcription factors (in corresponding protein-DNA networks). At the network level, these TF-protein co-complexes were visualized along with their regulatory relationships to the other (non-transcriptional) modules they regulate. Evolutionary comparison of these co-regulated complexes suggested the possibility that protein complexes may evolve with slower dynamics than protein-DNA transcriptional relationships. Related studies exploring co-regulated complexes in yeast have revealed cross-pathway communication between hyperosmotic, heat shock and oxidative stress response systems59, and elucidated signaling networks active during pheromone response53.

Protein-DNA interactions have also been combined with metabolic networks to understand the effects of transcriptional regulation on biochemical output84,85,91,155-157. For instance, a method called PROM (probabilistic regulation of metabolism) was developed to facilitate automated and quantitative integration of regulatory interactions and other high-throughput data for constraint-based modeling of metabolic networks157. The method was applied for genome-scale analysis of an integrative metabolic-regulatory network model for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, incorporating information from over 2,000 TF-gene promoter interactions regulating 3,300 metabolic reactions, 1,300 expression profiles, and 1,905 deletion phenotypes from E. coli and M. tuberculosis. The method enabled powerful prediction of microbial growth phenotypes under various environmental perturbations and aided in identification of novel gene functions. Furthermore, the study isolated several transcription factor hubs (see glossary) regulating multiple target proteins in the pathogen-interactome as a strategy for uncovering promising anti-microbial drug-targets.

Combined application of integrative approaches

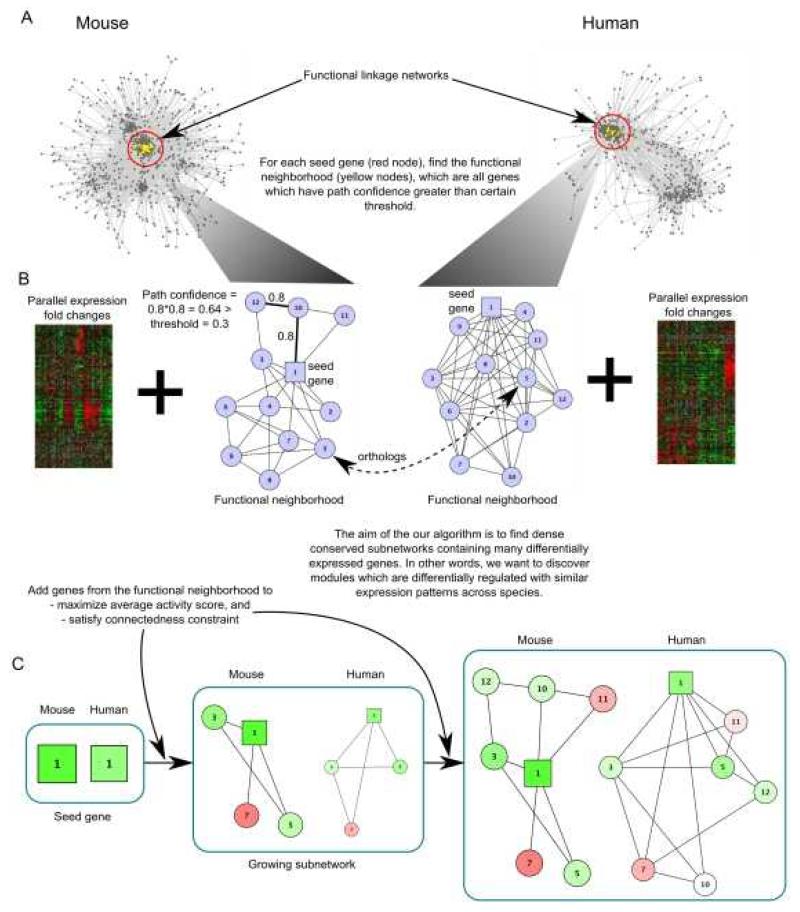

Given the above four integrative approaches, a very recent trend has been to chain together more than one of these to create network analysis pipelines of increasing sophistication and complexity. For example, network module-finding methods based on integration across molecular profiles and network types (e.g., for finding active modules or composite modules) have been extended across species for extracting co-functional modules that are also conserved. A multi-species and scalable framework, neXus (Network-cross(X)-species-Search)158, was developed for discovering conserved functional modules derived through parallel expression profiling in multiple species (Figure 4). Specifically, a clustering based approach was used to extract sub-networks from functional linkage networks (incorporating a wide array of interaction and omics information) derived independently in mouse and human. Sub-networks were seeded from differentially expressed orthologues, and simultaneously expanded in both species. Using programmatic constrains to threshold candidate sub-networks by network connectivity and molecular activity, conserved active sub-networks were nominated, which showed significant differential activity in stem cells relative to differential cells and shared similar patterns of gene expression across mouse and human. An extended version of the cMonkey framework designed for simultaneous (over sequential) data-integration across multiple species159 (Table 1), further expands the scope of such analyses by allowing parallel evaluation of protein-protein interactions, transcriptomic data, sequence profiles, metabolic and signaling pathway models and comparative genomics from multiple species to infer conserved co-regulated modules.

Figure 4. Identification of conserved functional modules by integration of data across multiple species.

(A) Functional linkage networks are assembled from multiple lines of evidence (e.g., protein-protein and genetic interactions, gene expression, protein localization, phenotype, and sequence data) and integrated with differential gene-expression profiles, in this example derived from human and mouse tissues (stem cell and differentiated cells). Candidate seed genes (red) are defined as differentially expressed othologues). The functional neighborhood (yellow) of each seed gene is marked by genes whose path confidence (the product of linkage weights along the path) from the seed gene meets a specified threshold. (B) A search for modules seeks densely connected subnetworks of genes sharing similar patterns of expression in both species. (C) In this search, subnetworks are grown simultaneously in both species starting from the seed genes (red) and expanded through iterative addition of genes satisfying both of two criteria: first, the genes must be in the same functional neighborhood, and second, the genes must maximize a differential expression activity score. Differentially expressed genes are colored green (up) or red (down)

Another recent study160 mapped global genetic networks in the fission yeast S. pombe and compared them with integrated maps of existing genetic and protein-protein networks (composite modules) in the divergent budding yeast S. cerevisiae, with the aim of identifying conserved functional modules. The authors demonstrated a hierarchical model for evolution of genetic interactions: interactions among genes whose products were in the same protein complex showed the highest degree of conservation, those involved within the same biological process showed lower but still significant conservation, whereas those participating in different biological processes were poorly conserved. Conservation of cross-pathway interactions between distinct biological processes was observed on a larger scale. Together, these observations reveal functional and evolutionary design principles underlying modular organization of cellular networks.

With continued progress in integrative bioinformatics pipelines and expansion in data handling capabilities, potentially a very large combination of data types, conditions, species, time points and cell states should be amenable to joint evaluation for in-depth network analysis.

Perspective

The past decade has witnessed explosive growth in data on biological networks9-14,16,161,162 albeit with inherent limitations24, and largely from a static perspective130. The integrative approaches reviewed here substantially increase the scope, scale and depth of network analyses, by permitting joint interpretation of ensembles of biomedical information. While these strategies have greatly refined high-throughput data analysis by tackling several of its prevalent challenges such as variability in accuracy, coverage and context-specificity, even greater power for mining biological knowledge remains to be achieved by implementing a combination of such approaches. Such combination strategies encompassing multiple algorithms, data types, conditions and species contexts are likely to maximize performance, relevance and scope of module-assisted network analysis. Along these lines, for example, although it has not yet been attempted, it would be conceivable to analyze differential networks (Approach 3) across multiple species (Approach 2) to detect conserved dynamic modules and process-specific pathways. Another challenging direction would be to study the evolution of composite modules, as it is becoming increasingly clear that different network types exhibit specific evolutionary dynamics, with for example regulatory interactions evolving faster than genetic, protein and metabolic networks 163.

Module-based biomarkers derived through integrative network analyses also provide superior predictive performance in disease classification, especially when compared with single-gene disease markers that have been routinely annotated through genome wide association studies (GWAS)38,62,71,72,164,165. Future work on integrative network analyses will provide greater clues into pathway structures and highlight network-level dynamics underlying biological responses.

Supplementary Material

Online ‘at-a-glance’ summary.

Bioinformatics approaches for integrating molecular networks across various types of interaction data, omics profiles, conditions or species have demonstrated significant power for detection and interpretation of biological modules.

Module-discovery approaches are broadly classified into four categories: identification of ‘Active Modules’ through integration of networks and molecular profiles, identification of ‘Conserved Modules’ across multiple species, identification of ‘Differential Modules’ across different conditions, and identification of ‘Composite Modules’ through integration of different interaction types.

Active Modules mark regions of a network that are most active during a given cellular or disease response and can identify important biomarkers, disease mechanism and therapeutic targets.

Conserved Modules are revealed through alignment or comparison of networks across multiple species. Such modules reflect biologically important pathways that have been conserved over long evolutionary periods.

Differential Modules are identified through differential analyses of experimentally mapped interactions across multiple conditions.

Composite Modules are detected through simultaneous integration of diverse types of molecular interactions.

Such integrative approaches reviewed here substantially increase the scope, scale and depth of bioinformatics analysis, by permitting joint interpretation of ensembles of distinct biological information.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge NIH grants P41 GM103504 and P50 GM085764 in support of this work.

Glossary

- Epistasis

The phenomenon whereby one gene affects the phenotype (e.g., growth) of another gene

- Synthetic lethality

An extreme case of negative genetic epistasis in which mutation of two genes in combination, but not individually, causes a lethal phenotype

- Network topology

Overall arrangement of nodes and edges in a given network

- Network connectivity

Measure of network proximity between any two molecules (nodes), defined by the number of interactions (edges) separating them

- Degree

Number of interactions (edges) that a molecule (node) has in a network

- Betweenness centrality

A statistical intuition of how ‘central’ the status of a given molecule (node) or interaction (edge) is within a network, which is inferred by the fraction of shortest paths between all pairs of nodes that pass through a particular node or edge. The distribution of node betweenness centrality is thought to follow a power law

- Hubs

Molecules with highest number of interactions (degree) in a network

- Metabolic Flux

The flow of chemicals through any metabolic reaction (e.g., an enzymatic reaction). Constrain-based methods (e.g., flux balance analysis; FBA), optimize flux predictions in genome-scale metabolic networks using various constrains, most recently, including omics-information.

- Orthology

The evolutionary phenomenon whereby two genes with homologous sequences, descending from a common ancestor, are separated by a speciation event. Such genes are denoted as orthologues.

Biographies

Biography

Dr. Trey Ideker is Professor and Chief of Genetics at the UCSD School of Medicine. He received Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from MIT in Computer Science and his Ph.D. from University of Washington in Molecular Biology. Ideker is a pioneer in using genome-scale measurements to construct network models of the cell. His recent research includes mapping of networks governing the response to DNA damage and methods for network-based diagnosis of disease. Among Ideker’s accolades are the 2009 ISCB Overton Prize and features in the Scientist, Technology Review, New York Times, San Diego Union Tribune, and Forbes.

Dr. Mitra is a postdoctoral scholar in the laboratory of Dr. Trey Ideker at UCSD, Dept. of Medicine. Her research entails development and application of network-based approaches for systematic elucidation of biological and disease regulation. Her primary focus lies in delineating the network basis of cellular stress-response systems, particularly those relating to autophagy and aging. This work involves high-throughput experimental and computational pipelines for assembling large-scale maps of dynamic cellular networks. Dr. Mitra received her PhD in Genetics from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY in 2007. Her graduate work explored chromosomal genetics and stem cell therapies for application against human cancers.

Dr. Anne-Ruxandra Carvunis is a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, San Diego, where she conducts research in systems biology and evolutionary biology under the supervision of Professor Trey Ideker. She received a Bachelor’s degree in Biology, a Magistere title in Biology/Biochemistry, and a Master’s degree in Neuroscience from the Universite Paris VI and the Ecole Normale Superieure de Paris. She also holds a Master’s degree in Interdisciplinary Approaches to Life Sciences from the Universite Paris VII and the Ecole Normale Superieure de Paris. She received a PhD in Bioinformatics in 2011 from the University of Grenoble, France.

Mr. Sanath Kumar Ramesh received his Master’s degree in computer science from University of California San Diego. His research work in the laboratory of Prof. Trey Ideker focused on developing bioinformatics tools for functional analysis of biological networks using heterogeneous data driven models. His current interests involve solving data-storage and other computational challenges faced in high-throughput network analyses as well as in creating network visualization platforms.

References

- 1.Hartwell LH, Hopfield JJ, Leibler S, Murray AW. From molecular to modular cell biology. Nature. 1999;402:C47–52. doi: 10.1038/35011540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alon U. Biological networks: the tinkerer as an engineer. Science. 2003;301:1866–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1089072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuart JM, Segal E, Koller D, Kim SK. A gene-coexpression network for global discovery of conserved genetic modules. Science. 2003;302:249–55. doi: 10.1126/science.1087447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal E, et al. Module networks: identifying regulatory modules and their condition-specific regulators from gene expression data. Nat Genet. 2003;34:166–76. doi: 10.1038/ng1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-baseda approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–13. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spirin V, Mirny LA. Protein complexes and functional modules in molecular networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12123–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2032324100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito T, et al. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4569–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stelzl U, et al. A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome. Cell. 2005;122:957–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harbison CT, et al. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravasi T, et al. An atlas of combinatorial transcriptional regulation in mouse and man. Cell. 2010;140:744–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costanzo M, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins SR, et al. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature. 2007;446:806–10. doi: 10.1038/nature05649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rual JF, et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, et al. High-quality binary protein interaction map of the yeast interactome network. Science. 2008;322:104–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1158684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muers M. Systems biology: Plant networks. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:586. doi: 10.1038/nrg3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milo R, et al. Network motifs: simple building blocks of complex networks. Science. 2002;298:824–7. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5594.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ideker T, Sharan R. Protein networks in disease. Genome Res. 2008;18:644–52. doi: 10.1101/gr.071852.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyuturk M. Algorithmic and analytical methods in network biology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:277–92. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fields S. High-throughput two-hybrid analysis. The promise and the peril. FEBS J. 2005;272:5391–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phizicky EM, Fields S. Protein-protein interactions: methods for detection and analysis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:94–123. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.94-123.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Hur A, Noble WS. Kernel methods for predicting protein-protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i38–46. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang H, Jedynak BM, Bader JS. Where have all the interactions gone? Estimating the coverage of two-hybrid protein interaction maps. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkatesan K, et al. An empirical framework for binary interactome mapping. Nat Methods. 2009;6:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1280. A critical discussion of biases in high-throughput data analyses that contribute to false positives and negative interpretations.

- 25.Cusick ME, et al. Literature-curated protein interaction datasets. Nat Methods. 2009;6:39–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards AM, et al. Too many roads not taken. Nature. 2011;470:163–5. doi: 10.1038/470163a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandyopadhyay S, et al. Rewiring of genetic networks in response to DNA damage. Science. 2010;330:1385–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1195618. Study outlining a recent bioinformatics approach for quantitative and differential analysis of genetic networks, applied to the mapping of DNA-damage response pathways in yeast.

- 28.Califano A. Rewiring makes the difference. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7 doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandyopadhyay T.I.a.S. Integrative systems biology. Nature genetics. 2010;42 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenssen TK, Laegreid A, Komorowski J, Hovig E. A literature network of human genes for high-throughput analysis of gene expression. Nat Genet. 2001;28:21–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jansen R, Greenbaum D, Gerstein M. Relating whole-genome expression data with protein-protein interactions. Genome Res. 2002;12:37–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.205602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Lichtenberg U, Jensen LJ, Brunak S, Bork P. Dynamic complex formation during the yeast cell cycle. Science. 2005;307:724–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1105103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segal E, Wang H, Koller D. Discovering molecular pathways from protein interaction and gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl 1):i264–71. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunsalus KC, et al. Predictive models of molecular machines involved in Caenorhabditis elegans early embryogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:861–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen LJ, Jensen TS, de Lichtenberg U, Brunak S, Bork P. Co-evolution of transcriptional and post-translational cell-cycle regulation. Nature. 2006;443:594–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R, et al. Personal omics profiling reveals dynamic molecular and medical phenotypes. Cell. 2012;148:1293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leiserson MD, Blokh D, Sharan R, Raphael BJ. Simultaneous identification of multiple driver pathways in cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1003054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nibbe RK, Koyuturk M, Chance MR. An integrative -omics approach to identify functional sub-networks in human colorectal cancer. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Begley TJ, Rosenbach AS, Ideker T, Samson LD. Hot spots for modulating toxicity identified by genomic phenotyping and localization mapping. Mol Cell. 2004;16:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo Z, et al. Edge-based scoring and searching method for identifying condition-responsive protein-protein interaction sub-network. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2121–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu J, Chen Y, Li S, Li Y. Identification of responsive gene modules by network-based gene clustering and extending: application to inflammation and angiogenesis. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:47. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Z, Zhao X, Chen L. Identifying responsive functional modules from protein-protein interaction network. Mol Cells. 2009;27:271–7. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dittrich MT, Klau GW, Rosenwald A, Dandekar T, Muller T. Identifying functional modules in protein-protein interaction networks: an integrated exact approach. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:i223–31. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qiu YQ, Zhang S, Zhang XS, Chen L. Detecting disease associated modules and prioritizing active genes based on high throughput data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prelic A, et al. A systematic comparison and evaluation of biclustering methods for gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1122–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharan R, Ulitsky I, Shamir R. Network-based prediction of protein function. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:88. doi: 10.1038/msb4100129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ideker T, Ozier O, Schwikowski B, Siegel AF. Discovering regulatory and signalling circuits in molecular interaction networks. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(Suppl 1):S233–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sohler F, Hanisch D, Zimmer R. New methods for joint analysis of biological networks and expression data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1517–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cabusora L, Sutton E, Fulmer A, Forst CV. Differential networkexpression during drug and stress response. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2898–905. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott J, Ideker T, Karp RM, Sharan R. Efficient algorithms for detecting signaling pathways in protein interaction networks. J Comput Biol. 2006;13:133–44. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2006.13.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nacu S, Critchley-Thorne R, Lee P, Holmes S. Gene expression network analysis and applications to immunology. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:850–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang SS, Fraenkel E. Integrating proteomic, transcriptional, and interactome data reveals hidden components of signaling and regulatory networks. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra40. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chowdhury SA, Koyutürk M. Identification of coordinately dysregulated subnetworks in complex phenotypes. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2010:133–44. doi: 10.1142/9789814295291_0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dao P, et al. Optimally discriminative subnetwork markers predict response to chemotherapy. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:i205–13. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fortney K, Kotlyar M, Jurisica I. Inferring the functions of longevity genes with modular subnetwork biomarkers of Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ulitsky I, Shamir R. Identifying functional modules using expression profiles and confidence-scored protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1158–64. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang YC, Chen BS. Integrated cellular network of transcription regulations and protein-protein interactions. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breitling R, Amtmann A, Herzyk P. Graph-based iterative Group Analysis enhances microarray interpretation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajagopalan D, Agarwal P. Inferring pathways from gene lists using a literature-derived network of biological relationships. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:788–93. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chuang HY, Lee E, Liu YT, Lee D, Ideker T. Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:140. doi: 10.1038/msb4100180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hwang T, Park T. Identification of differentially expressed subnetworks based on multivariate ANOVA. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klammer M, Godl K, Tebbe A, Schaab C. Identifying differentially regulated subnetworks from phosphoproteomic data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:351. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao XM, Wang RS, Chen L, Aihara K. Uncovering signal transduction networks from high-throughput data by integer linear programming. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e48. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Backes C, et al. An integer linear programming approach for finding deregulated subgraphs in regulatory networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vandin F, Upfal E, Raphael BJ. Algorithms for detecting significantly mutated pathways in cancer. J Comput Biol. 2011;18:507–22. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2010.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Komurov K, White MA, Ram PT. Use of data-biased random walks on graphs for the retrieval of context-specific networks from genomic data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reiss DJ, Baliga NS, Bonneau R. Integrated biclustering of heterogeneous genome-wide datasets for the inference of global regulatory networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vaske CJ, et al. Inference of patient-specific pathway activities from multi-dimensional cancer genomics data using PARADIGM. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i237–45. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Integrate d genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v474/n7353/full/nature10166.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. A genome-scale effort for mapping significantly mutated pathways in human cancer through network projection of mutational profiles, leading to the identification of novel disease mechanisms.

- 73.Ciriello G, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Mutual exclusivity analysis identifies oncogenic network modules. Genome Res. 2012;22:398–406. doi: 10.1101/gr.125567.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miller CA, Settle SH, Sulman EP, Aldape KD, Milosavljevic A. Discovering functional modules by identifying recurrent and mutually exclusive mutational patterns in tumors. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:34. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Network TC. Corrigendum: Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2013;494:506. doi: 10.1038/nature11903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lan A, et al. ResponseNet: revealing signaling and regulatory networks linking genetic and transcriptomic screening data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W424–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Komurov K, Dursun S, Erdin S, Ram PT. NetWalker: a contextual network analysis tool for functional genomics. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rives AW, Galitski T. Modular organization of cellular networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1128–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237338100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ravasz E, Barabasi AL. Hierarchical organization in complex networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2003;67:026112. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.67.026112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hanisch D, Zien A, Zimmer R, Lengauer T. Co-clustering of biological networks and gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(Suppl 1):S145–54. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gonzalez O, Zimmer R. Contextual analysis of RNAi-based functional screens using interaction networks. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2707–13. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luscombe NM, et al. Genomic analysis of regulatory network dynamics reveals large topological changes. Nature. 2004;431:308–12. doi: 10.1038/nature02782. This article presents an omics-based mapping of stress-response pathways in yeast protein networks, revealing key regulatory insights into network dynamics.

- 83.Tanay A, Sharan R, Kupiec M, Shamir R. Revealing modularity and organization in the yeast molecular network by integrated analysis of highly heterogeneous genomewide data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2981–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308661100. This study develops and integrates a widely cited approach for module-discovery allowing simultaneous interpretation of a diverse array of biological information.

- 84.Blazier AS, Papin JA. Integration of expression data in genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions. Front Physiol. 2012;3:299. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lewis NE, Nagarajan H, Palsson BO. Constraining the metabolic genotype-phenotype relationship using a phylogeny of in silico methods. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:291–305. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schellenberger J, et al. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: the COBRA Toolbox v2.0. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1290–307. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Calvano SE, et al. A network-based analysis of systemic inflammation in humans. Nature. 2005;437:1032–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yeger-Lotem E, et al. Bridging high-throughput genetic and transcriptional data reveals cellular responses to alpha-synuclein toxicity. Nat Genet. 2009;41:316–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xue H, et al. A modular network model of aging. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:147. doi: 10.1038/msb4100189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bandyopadhyay S, Kelley R, Ideker T. Discovering regulated networks during HIV-1 latency and reactivation. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2006:354–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Haugen AC, et al. Integrating phenotypic and expression profiles to map arsenic-response networks. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R95. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shlomi T, Cabili MN, Herrgard MJ, Palsson BO, Ruppin E. Network-based prediction of human tissue-specific metabolism. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1003–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Colijn C, et al. Interpreting expression data with metabolic flux models: predicting Mycobacterium tuberculosis mycolic acid production. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Price ND, Reed JL, Palsson BO. Genome-scale models of microbial cells: evaluating the consequences of constraints. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:886–97. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chowdhury SA, Nibbe RK, Chance MR, Koyuturk M. Subnetwork state functions define dysregulated subnetworks in cancer. J Comput Biol. 2011;18:263–81. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2010.0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Anastassiou D. Computational analysis of the synergy among multiple interacting genes. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:83. doi: 10.1038/msb4100124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ma X, Lee H, Wang L, Sun F. CGI: a new approach for prioritizing genes by combining gene expression and protein-protein interaction data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:215–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li W, et al. Dynamical systems for discovering protein complexes and functional modules from biological networks. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2007;4:233–50. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2007.070210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang P, Li X, Wu M, Kwoh CK, Ng SK. Inferring gene-phenotype associations via global protein complex network propagation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tu Z, et al. Integrating siRNA and protein-protein interaction data to identify an expanded insulin signaling network. Genome Res. 2009;19:1057–67. doi: 10.1101/gr.087890.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Taylor IW, et al. Dynamic modularity in protein interaction networks predicts breast cancer outcome. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1522. An omics-based strategy for identifying breast cancer pathways, demonstrating the power of integrative network analysis for disease prognosis.

- 102.Zhang X, et al. The expanded human disease network combining protein-protein interaction information. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:783–8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bapat SA, Krishnan A, Ghanate AD, Kusumbe AP, Kalra RS. Gene expression: protein interaction systems network modeling identifies transformation-associated molecules and pathways in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4809–19. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang KX, Ouellette BF. CAERUS: predicting CAncER oUtcomeS using relationship between protein structural information, protein networks, gene expression data, and mutation data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1001114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ma H, Schadt EE, Kaplan LM, Zhao H. COSINE: COndition-SpecIfic sub-NEtwork identification using a global optimization method. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1290–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ahn J, Yoon Y, Park C, Shin E, Park S. Integrative gene network construction for predicting a set of complementary prostate cancer genes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1846–53. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wu Z, Zhao XM, Chen L. A systems biology approach to identify effective cocktail drugs. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4(Suppl 2):S7. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-S2-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vespignani A. Evolution thinks modular. Nat Genet. 2003;35:118–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1003-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mazurie A, Bonchev D, Schwikowski B, Buck GA. Evolution of metabolic network organization. BMC Syst Biol. 2010;4:59. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Odom DT, et al. Tissue-specific transcriptional regulation has diverged significantly between human and mouse. Nat Genet. 2007;39:730–2. doi: 10.1038/ng2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wuchty S, Oltvai ZN, Barabasi AL. Evolutionary conservation of motif constituents in the yeast protein interaction network. Nat Genet. 2003;35:176–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Matthews LR, et al. Identification of potential interaction networks using sequence-based searches for conserved protein-protein interactions or #x201C;interologs#x201D; Genome Res. 2001;11:2120–6. doi: 10.1101/gr.205301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yu H, et al. Annotation transfer between genomes: protein-protein interologs and protein-DNA regulogs. Genome Res. 2004;14:1107–18. doi: 10.1101/gr.1774904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sharan R, Ideker T. Modeling cellular machinery through biological network comparison. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:427–33. doi: 10.1038/nbt1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kelley BP, et al. PathBLAST: a tool for alignment of protein interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W83–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sharan R, et al. Conserved patterns of protein interaction in multiple species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1974–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409522102. This study highlights a method for pair-wise alignment of sub-networks to facilitate efficient comparisons of diverse interactomes.

- 117.Kalaev M, Bafna V, Sharan R. Fast and accurate alignment of multiple protein networks. J Comput Biol. 2009;16:989–99. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2009.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bandyopadhyay S, Sharan R, Ideker T. Systematic identification of functional orthologs based on protein network comparison. Genome Res. 2006;16:428–35. doi: 10.1101/gr.4526006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]