Abstract

Prophylaxis of the first bleeding from esophageal varices became a clinical option more than 20 years ago, and gained a large diffusion in the following years. It is based on the use of nonselective beta-blockers, which decreases portal pressure, or on the eradication of esophageal varices by endoscopic band ligation of varices. In patients with medium or large varices either of these treatments is indicated. In patients with small varices only medical treatment is feasible, and in patients with medium and large varices with contraindication or side-effects due to beta-blockers, only endoscopic band ligation may be used. In this review the rationale and the results of the prophylaxis of bleeding from esophageal varices are discussed.

Keywords: beta-blockers, band ligation, portal hypertension

Abbreviation: RWM, red wale marks

In historical terms, prophylaxis of the first variceal bleeding came last within the context of varices management, over the last decade on the past century. This was after the treatment of acute variceal bleeding, which was initially defined in the ‘50s, and the prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding, which started to be effectively treated in the ‘70s. Being the last management step, researchers and doctors were able to take advantage of the pathophysiological investigations which were previously performed in portal hypertension, and of the experience accumulated for purposes of slightly different but still related clinical indications.

Natural history of growth of esophageal varices

The median time from the occurrence of cirrhosis to the development of esophageal varices is difficult to determine, due to the uncertainty in the time of onset of cirrhosis. However, in patients with established cirrhosis without varices, a roughly linear course of occurrence of varices was observed, with an incidence around 9% per year.1 A higher Child-Pugh score was not a risk factor for the occurrence of varices,2 confirming the linearity of the course, but the observation of worsening liver function3 or low platelet count and prolongation of prothrombin time were predictors of occurrence of varices. After the occurrence of varices, an aggravation was more frequent in patients with alcoholic etiology or with more advanced liver disease.1

It was suggested4 that the presence of a patent para-umbilical vein, being a collateral circulation that does not feed the esophageal varices, may bear a protective role on variceal occurrence and rupture. The observation5 that in a prospective study the rate of formation of esophageal varices in patients without varices at the beginning of follow-up was not influenced by the presence or absence of a patent para-umbilical vein contrast with this hypothesis, and is consistent with the concept that abdominal collaterals are a hint of a more advanced step in the natural history of the disease, and they tend to progress in agreement.

Patients without oesophageal varices (pre-primary prevention)

The prevention of the formation of oesophageal varices would be clinically relevant, since it would abolish the risk of variceal bleeding from the beginning, by treating patients who have not yet developed this complication. A strategy for prevention would also be reasonable, since the formation of varices is a very frequent event in the course of the disease.

Because of the difficulties in performing long-term intervention studies in patients without a clinically relevant condition, to date, only one trial has been performed on the prevention of varices formation.6 This was a multicentre double-blind study in 213 patients with documented cirrhosis, portal hypertension defined as HVPG ≥ 6 mmHg, without oesophageal or gastric varices on endoscopy, aimed at comparing the occurrence of varices in patients treated with a nonselective beta-blocker (timolol) versus placebo. Patients randomized to timolol showed a significant decrease in HVPG, but the percentage of patients who did not reach the primary end-point (formation of varices or variceal bleeding) was nearly identical in the two groups.

This disappointing conclusion was interpreted as suggesting that in these patients, the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to portal hypertension (hyperdynamic circulation and increase in portal inflow) were weakly operating, and that non-selective beta-blockers might have been ineffective because of the lack of the target on which they are meant to operate. An alternative explanation is that the effect might have been too small to be demonstrated, in relation to the study size and the length of follow-up. Indeed, during the study, nearly half of the patients were withdrawn from treatment or decreased the dose, and 20% were non compliant. No further trial has assessed this issue, and it is unlikely that this might be done in the near future. According to the available evidence, all clinical practice guidelines7,8 agree that beta-blockers cannot be recommended to prevent the formation of oesophageal varices.

Risk of bleeding in relation to the characteristics of esophageal varices

After the formation of varices, their risk of bleeding is variable, and is related to several factors, including the size and the features of the varices, and the severity of the underlying liver dysfunction. According to the ‘explosive theory’ of variceal rupture,9 varices rupture because the wall tension overwhelms the resistance of the variceal tissue, and the wall tension progressively increases in relation to the increase in variceal size and transmural pressure, and the decrease in wall thickness. In agreement with such theory, the most utilized and documented predictive index of first variceal bleeding, the NIEC index,10 which was proposed within the context of a multicentre study and then validated in several different settings, contains a semi-quantitative classification of variceal size, the presence of red wale marks (i.e. the expression of a very thin wall), and the Child-Pugh class, which is considered a surrogate marker of portal pressure (i.e. the transmural pressure within a varix, which cannot be easily measured in the general population).

According to this index (Table 1), one year risk of bleeding may vary from 6 to 76%, according to the characteristics of the varices and of the patient. Different predictive indexes,11 or modifications of the NIEC index,12 albeit more precise in their predictive ability, have not gain the popularity of the original index.

Table 1.

Estimated risk of a first variceal bleeding according to the parameters included in the NIEC index (Ref. 10). RWM = red wale marks.

| Child-Pugh A |

Child-Pugh B |

Child-Pugh C |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | Small | Medium | Large | Small | Medium | Large | |

| RWM 0 | 6 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 26 | 20 | 30 | 42 |

| RWM 1+ | 8 | 12 | 19 | 15 | 23 | 33 | 28 | 38 | 54 |

| RWM 2+ | 12 | 16 | 24 | 20 | 30 | 42 | 36 | 48 | 64 |

| RWM 3+ | 16 | 23 | 34 | 28 | 40 | 52 | 44 | 60 | 76 |

In consideration of the large spectrum of bleeding risk in patients with varices, it is apparent that any clear-cut separation between small (or low-risk) varices, and large (or high-risk) varices is arbitrary, and should be based on reasonably simple criteria. Generally, varices are considered small if the largest varix is small than 5 mm (i.e. the opening size of an endoscopic biopsy forceps), or F1 according to the Japanese classification (linear varices occupying less than 1/3 of the oesophageal radius), or varices occupying less than 25% of the oesophageal lumen according to the ILCP classification.

Usually, patients with small varices have an HVPG lower than that of patients with large varices, and the difference has been reported to be significant only in some series.13,14 Overall risk of a first variceal bleeding in untreated patients is around half that of patients with large varices but it is not negligible (approximately 10% at two years).10,11,15,16 Non-selective beta-blockers decrease portal pressure in patients with small varices to the same extent as they do in patients with large varices.17 Thus, patients with small varices are quantitatively rather than qualitatively different from patients with large varices, and represent an earlier stage of the same pathophysiological condition.

Prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in patients with small varices

Treating patients with small varices may be useful if the increase in size of the varices, which is associated with an increased risk of bleeding, can be delayed. This way, a decrease in bleeding risk should ensue. In addition, treating patients from the stage of small varices may have the additional benefit of abolishing the need for endoscopic surveillance of small varices, which is required to recognize a worsening of the varices, and the consequent change in treatment strategy. Since surveillance strategies generally imply an annual follow-up examination, and compliance to surveillance is often sub-optimal, starting treatment from small varices may be helpful in decreasing the risk of bleeding over the period of time between worsening of the varices and endoscopic proof of such worsening.

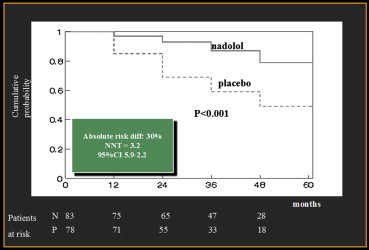

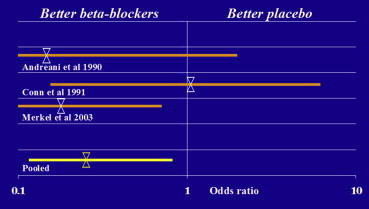

For these reasons, a few years ago we performed a randomized controlled trial aiming at assessing whether treatment with the beta-blocker nadolol in patients with cirrhosis and small esophageal varices delays variceal growth into large oesophageal varices and decreases the risk of bleeding.17 Eighty-three patients were randomized to nadolol and 78 to placebo; patients were followed for up to 60 months (Figure 1). Patients randomized to nadolol showed a decreased risk of variceal growth, a decreased risk of variceal bleeding but no significant decrease in mortality. It was concluded that in patients with small esophageal varices it is reasonable to start prophylaxis with non-selective beta-blockers. The lack of an effect on mortality was attributed to the sample size of the study, as very few patients in either arm died of variceal bleeding. No further trial has been performed to date. The only comparative data can be obtained by subgroup analyses of patients with small varices included in two trials of patients with large and small varices (mostly with large varices) treated with propranolol or placebo.18,19 A meta-analysis of such data is reported in Figure 2. In consideration of the limited amount of available data, practice guidelines are cautious, and suggests that such patients may (or should) be treated with beta-blockers although further studies are required to confirm their benefit.

Figure 1.

Course of the risk of growth of esophageal varices in patients treated with nadolol or placebo (from Ref. 17).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of beta-blockers versus. placebo in the prophylaxis of first variceal bleeding in patients with small esophageal varices.

Prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in patients with medium or large varices

Based on RCT and meta-analyses dating back over 20 years ago, it was clearly established that beta-blockers are effective in preventing the first variceal bleeding and decreasing the risk of death from bleeding.20 Over the same years, several trials assessed the use of endoscopic sclerotherapy within the same setting, with conflicting results; the observation of a relevant ‘quality effect’ (i.e. the beneficial effect was limited to trials of low quality) eventually led to the abandonment of this procedure in the prophylaxis setting.21

In the subsequent years, the endoscopic armamentarium was improved with the development of endoscopic band ligation, and it soon became apparent that this procedure was safer, more effective, and less prone to individual variations. A few trials showed that it was more effective than no treatment.22,23 A series of meta-analyses (Table 2) of the numerous trials comparing it to non-selective beta-blockers showed a better effect of endoscopic treatment,24–27 no difference in survival, and a tendency to a quality effect. Side-effects were more frequent but less severe with medical treatment. A series of potential bias sources were highlighted: i) the only trial showing significant improvement in outcome with band ligation had a very high rate of bleeding with beta-blockers but a very low dose of propranolol was given, suggesting sub-optimal medical treatment28; ii) a trial was interrupted at the time of the largest difference in bleeding in order to maximize the differences in outcome29; iii) in some trials follow-up was too short for a fair comparison between treatments28,30; iv) in one trial, only preliminary results were provided, and no full report was available several years from initial publication.30

Table 2.

A series of recent meta-analyses of endoscopic band ligation versus. nonselective beta-blockers in primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. Relative risk below 1.00 indicates advantage of endoscopic band ligation. Difference is statistically significant when CI does not cross the value of 1.

| Author | No. of pts. | RR bleeding | CI for bleeding | RR mortality | CI mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tripathi 2007 | 734 | 0.63 | 0.43–0.92 | 0.71 | 0.38–1.32 |

| Gluud 2007 | 1167 | 0.59 | 0.41–0.77 | 1.02 | 0.75–1.39 |

| Gluud 2007 (a) | 324 | 0.86 | 0.55–1.35 | 1.22 | 0.84–1.78 |

| Burroughs 2010 | 1364 | 0.50 | 0.37–0.67 | 0.94 | 0.70–1.28 |

| Li 2011 | 1023 | 0.79 | 0.61–1.02 | 1.06 | 0.86–1.30 |

Limited to trials with adequate bias control.

Recently, it has been suggested to replace the traditional NSBB, propranolol or nadolol, with carvedilol, an NSBB which has a partial anti-alpha-2 adrenergic activity, which may be helpful in decreasing the enhanced intrahepatic venous vasoconstriction. Indeed, carvedilol was shown to be more effective in decreasing HVPG than propranolol,31 and to decrease HVPG in patients nonresponder to propranolol,32 although there are also some contrasting observations.33 A single trial compared carvedilol to endoscopic band ligation in primary prophylaxis,34 and showed a lower incidence of variceal bleeding in patients receiving carvedilol. Further studies are required to completely define this issue.

Only a few studies have investigated the possible advantage of the association of NSBB and band ligation in comparison to either treatment alone in the primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding.35–37 A single study, the smallest in size36 was favorable to the association, while two did not show any difference in the rate of esophageal bleeding, overall gastrointestinal bleeding, or death. The lack of advantage of the association in this indication contrasts with the results obtained in the prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding.38,39 This may be related to the different risk of bleeding in the two settings. Indeed, the combination of two effective treatments in the setting of primary prophylaxis, where the treatment is intended to prevent an event with a relatively low incidence, may have no benefit because the addition of the side-effects of the two treatments eventually balances out any possible therapeutic improvement.

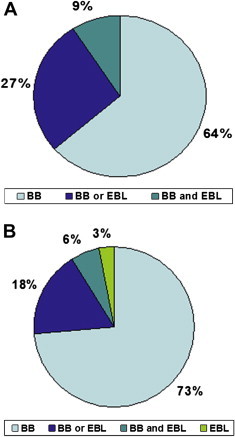

At the consensus workshop of Baveno V7 it was concluded that either non-selective beta-blockers or band ligation are recommended for the prevention of a first variceal bleeding of medium or large varices, and the choice should be based on local resources and expertise, patients' characteristics and preference, side-effects and contraindications. In addition, a survey reported at the same workshop concluded that among the faculty members of the conference, two/third considered NSBB the best approach, and three quarters used NSBB as first option in their practice (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Preference between nonselective beta-blockers and endoscopic band ligation in the survey of the expert panel participating to the Baveno V consensus conference (2010). Panel A: answers to the question: “what do you consider the best approach for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding?”; panel B: answers to the question: “In your current clinical practice for primary prophylaxis, which is the first option?”.

Treatment of patients with contraindication or side-effects due to beta-blockers

Contraindications to beta-blockers in patients with portal hypertension are the same as in patients with different diseases. The major contraindications are reported in Table 3. To rule out possible contraindications, history, physical examination and standard ECG are sufficient.

Table 3.

Contraindications to nonselective beta-blockers in portal hypertension.

|

In patients with contraindication, therapeutic options are limited. The use of long-acting nitrates alone has been suggested, based on the observation that in a single trial they were shown to be of similar efficacy as non-selective beta-blockers in patients without contraindications.40 However, in a trial especially designed to address this point, isosorbide mononitrate was not better than placebo in preventing bleeding or death after a follow-up of 2 years.41

Band ligation appears to be a suitable option, since it has been shown to be at least as effective as non-selective beta-blockers in several trials. The usefulness in patients with contraindications or side-effects due to beta-blockers is not so clearly demonstrated, as in patients who cannot be treated with the first line treatment, a lower efficacy is expected also with another treatment, because of co-morbidity, lower compliance, and further, poorly defined factors. Indeed, in a randomized trial of ligation versus no treatment in patients unable to take beta-blockers, Triantos42 showed disappointing results (5/25 bleeds in the treatment arm versus 2/27 in the no treatment arm), which determined premature interruption of the trial. However, it should be observed that the difference in bleeding rate in this study was not statistically significant. At odds with the above results, Dell'Era et al43 reported similar bleeding rates in patients with contraindications/intolerance to beta-blockers treated with band ligation compared to patients who were non-responders to beta-blockers and had been switched to band ligation. Combining these pieces of evidence, the Baveno V consensus conference concluded that these patients should be treated with band ligation.

Conclusions

-

•

The prevention of the first bleeding is a cornerstone in the treatment of portal hypertension.

-

•

Based on the patients' conditions and the features of the varices, there is a role for both pharmacological and endoscopic treatment.

-

•

It is expected that patients will receive the best treatment in centers where both treatments are available with the same level of expertise.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgments

This review is based on the Dr. S. R. Naik Memorial Oration given on March 23rd, 2013, at the 21st Annual Conference of Indian National Association for Study of the Liver (INASL) held in Hyderabad, India.

References

- 1.Merli M., Nicolini G., Angeloni S. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2003;38:266–272. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zoli M., Merkel C., Magalotti D. Natural history of cirrhotic patients with small esophageal varices: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:503–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calès P., Desmorat H., Vinel J.P. Incidence of large oesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: application to prophylaxis of first bleeding. Gut. 1990;31:1298–1302. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.11.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mostbeck G.H., Wittich G.R., Herold C. Hemodynamic significance of the paraumbilical vein in portal hypertension: assessment by duplex US. Radiology. 1989;170:339–342. doi: 10.1148/radiology.170.2.2643137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berzigotti A., Merkel C., Magalotti D. New abdominal collaterals at ultrasound: a clue of progression of portal hypertension. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groszmann R.J., Garcia-Tsao G., Bosch J. Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2254–2261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Franchis R., Bosch J., Burroughs A.K. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Tsao G., Sanyal A.J., Grace N.D., Carey W., Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conn H.O. The varix volcano connection. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:1333–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North Italian Endoscopic club for the study and treatment of oesophageal varices Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988:983–989. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoli M., Merkel C., Magalotti D., Marchesini G., Gatta A., Pisi E. Evaluation of a new endoscopic index to predict first bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1996;24:1047–1052. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v24.pm0008903373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merkel C., Zoli M., Siringo S. Prognostic indicators of risk of first variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a multicenter study in 711 patients to validate and improve the NIEC index. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2915–2920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gluud C., Henriksen J.H., Nielsen G. Prognostic indicators in alcoholic cirrhotic man. Hepatology. 1988;8:222–227. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuin R., Gatta A., Merkel C. Evaluation of peritoneoscopic and oesophagoscopic findings as indexes of portal hypertension in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1982;14:214–219. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prada A., Bortoli A., Minoli G., Carnovali M., Colombo E., Sangiovanni A. Prediction of esophageal variceal bleeding – evaluation of the Beppu and North Italian Endoscopic Club Scores by an independent group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6:1009–1013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigo G.P., Merighi A., Chahin N.J. A prospective study of the ability of three endoscopic classifications to predict haemorrhage from esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merkel C., Marin R., Angeli P. A placebo-controlled clinical trial of nadolol in the prophylaxis of growth of small esophageal varices in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:476–484. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreani T., Poupon R.E., Balkau B.J. Preventive therapy of first gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: results of a controlled trial comparing propranolol, endoscopic sclerotherapy and placebo. Hepatology. 1990;12:1413–1419. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conn H.O., Grace N.D., Bosch J. Propranolol in the prevention of the first hemorrhage from esophagogastric varices: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. Hepatology. 1991;13:902–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poynard T., Calès P., Pasta L. Beta-adrenergic-antagonist drugs in the prevention of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis and esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1532–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199105303242202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagliaro L., D’Amico G., Soerensen T.I. Prevention of first bleeding in cirrhosis. A meta-analysis of randomized trials of nonsurgical treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:59–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarin S.K., Guptan R.K., Jain A.K., Sundaram K.R. A randomized controlled trial of endoscopic variceal band ligation for primary prophylaxis of varicel bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:337–342. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lay C.S., Tsai Y.T., Teg C.Y. Endoscopic variceal ligation in prophylaxis of first variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with high-risk esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1997;25:1346–1350. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tripathi D., Graham C., Hayes P.C. Variceal band ligation versus beta-blockers for primary prevention of variceal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:835–845. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282748f07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gluud L.L., Klingenberg S., Nikolova D., Gluud C. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2842–2848. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burroughs A.K., Tsochatzis E.A., Triantos C. Primary prevention of variceal haemorrhage: a pharmacological approach. J Hepatol. 2010;52:946–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L., Yu C., Li Y. Endoscopic band ligation versus pharmacological therapy for variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:147–155. doi: 10.1155/2011/346705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarin S.K., Lamba G.S., Kumar M., Misra A., Murthy N.S. Comparison of endoscopic ligation and propranolol for the primary prevention of variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:988–993. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904013401302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jutabha R., Jensen D.M., Martin P., Savides T., Han S.H., Gornbein J. Randomized study comparing banding and propranolol to prevent initial variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotics with high-risk esophageal varices. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:870–881. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De B.K., Ghoshal U.C., Das T., Santra A., Biswas P.K. Endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of oesophageal variceal bleed: preliminary report of a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:220–224. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banares R., Moitinho E., Piqueras B. Carvedilol, a new nonselective beta-blocker with intrinsic anti alpha-1 adrenergic activity, has a greater portal hypotensive effect than propranolol in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;30:79–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reilberger T, Ulbrich G, Ferlitsch A, et al. Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranolol. Gut. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.De B.K., Das D., Sen S. Acute and 7-day portal pressure response to carvedilol and propranolol in cirrhotics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:183–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripathi D., Ferguson J.W., Kochar N. Randomized controlled trial of carvedilol versus variceal band ligation for the prevention of the first variceal bleed. Hepatology. 2009;50:825–833. doi: 10.1002/hep.23045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarin S.K., Wadhawan M., Agarwal S.R., Tyagi P., Sharma B.C. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus propranolol versus endoscopic variceal ligation alone in primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:797–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gheorghe C., Gheorghe L., Iacob S., Iacob R., Popescu I. Primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotics awaiting liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:552–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lo G.H., Chen W.C., Wang H.M., Lee C.C. Controlled trial of ligation plus nadolol versus nadolol alone for the prevention of first variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2010;52:230–237. doi: 10.1002/hep.23617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lo G.H., Lai K.H., Cheng J.S. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus nadolol and sucralfate compared with ligation alone for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: a prospective, randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:461–465. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de la Peña J., Brullet E., Sanchez-Hernández E. Variceal ligation plus nadolol compared with ligation for prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding: a multicenter trial. Hepatology. 2005;41:572–578. doi: 10.1002/hep.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angelico M., Carli L., Piat C., Gentile S., Capocaccia L. Effects of isosorbide-5-mononitrate compared with propranolol on first bleeding and long-term survival in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1632–1639. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Pagan J.C., Villanueva C., Vila M.C. Isosorbide mononitrate in the prevention of first bleed in patients who cannot receive beta-blockers. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:908–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Triantos C., Vlachogiannakos J., Armonis A. Primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotics unable to take beta-blockers: a randomized trial of ligation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1435–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dell'Era A., Sotela J.C., Fabris F.M. Primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients: a cohort study. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:936–943. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]