Abstract

Frequency modulations (FMs) are prevalent in human speech, and are important acoustic cues for the categorical discrimination of phonetic contrasts. For bats, FM sweeps are also important for communication and are often the only component in echolocation calls. Auditory neurons tuned to the direction and rate of FM might underlie the encoding of rapid frequency transitions. In the mustached bat, we have discovered a population of such FM selective cells in an area interposed between the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC) and the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL). We believe this area to be the ventral extent of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv). To describe FM selectivity of neurons in the ICXv and to compare it to other midbrain nuclei, up- and down-sweeping linear FM stimuli were presented at different modulation rates. Extracellular recordings were made from 171 single units in the ICC, ICXv, and NLL of 10 mustached bats. In the ICXv, there was a much higher degree of FM selectivity than in ICC or NLL and a consistent preference for upward over downward FM sweeps. Anterograde and retrograde transport was examined following focal injections of wheatgerm agglutinin-horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP) into ICXv. The main targets of anterograde transport were the deep layers of the superior colliculus and the suprageniculate division of the medial geniculate body. The primary site of retrograde transport was the nucleus of the central acoustic tract in the brainstem. Thus, the ICXv appears to be a part of the central acoustic tract, an extralemniscal pathway linking the auditory brainstem directly to a multimodal nucleus of the thalamus.

Indexing terms: central acoustic tract, external nucleus of the inferior colliculus, suprageniculate nucleus, superior colliculus, lateral inhibition, temporal processing

Rapid frequency modulations (FMs) are prominent components of the communication sounds of many species. Parnell’s mustached bat (Pteronotus parnelli) is a good example, with an extensive repertoire of communication sounds rich in multiharmonic frequency modulations. A study in which several hundred nonbiosonar vocalizations of Pteronotus were analyzed revealed 16 simple and 13 composite “syllable” groups (Kanwal et al., 1994). Some syllables consist primarily of FM sounds. FM depth (i.e., bandwidth) and rate are parameters that distinguish one syllable from another. This bat also emits an echolocation call with prominent FM components. The FM component of the echolocation call is utilized for target ranging (Cahlander et al., 1965), and characterization of target fine structure.

Speech also contains rapid FMs, called formant transitions, that are important cues for the perception of certain phonemes. Formant transitions can differ in direction (up vs. down) and rate (rapid vs. slow) of frequency change. For example, the phonemes /ba/ and /da/ differ only in the direction of one formant transition, whereas /ba/ and /wa/ differ in only the rate of their formant transitions (Kent and Read, 1992).

FM sweeps in bat echolocation sounds are very rapid, typically under 10 ms (Fig. 1). Even the longest FM components of mustached bat communication sounds are under 50 ms. The rapidity of frequency change in such signals presents a spectrotemporal encoding challenge for the auditory system. Auditory neurons known as an FM-processing or FM-selective cells are well suited to discriminate between rapid FMs that vary in direction or rate of frequency change. Many studies have documented various types of FM-selective neurons that prefer different directions and rates of frequency change (Whitfield and Evans, 1965; Suga, 1965a, 1968; Nelson et al., 1966; Erulkar et al., 1968; Suga and Schlegel, 1973; Møller, 1974; Mendelson and Cynader, 1985; Phillips et al., 1985; Poon et al., 1990, 1991; Heil et al., 1992b; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Mendelson et al., 1993; Fuzessery, 1994; Tian and Rauschecker, 1994; Fuzessery and Hall, 1996; Heil and Irvine, 1998). Thus, these neurons may be important for encoding and discriminating FM in communication and echolocation sounds.

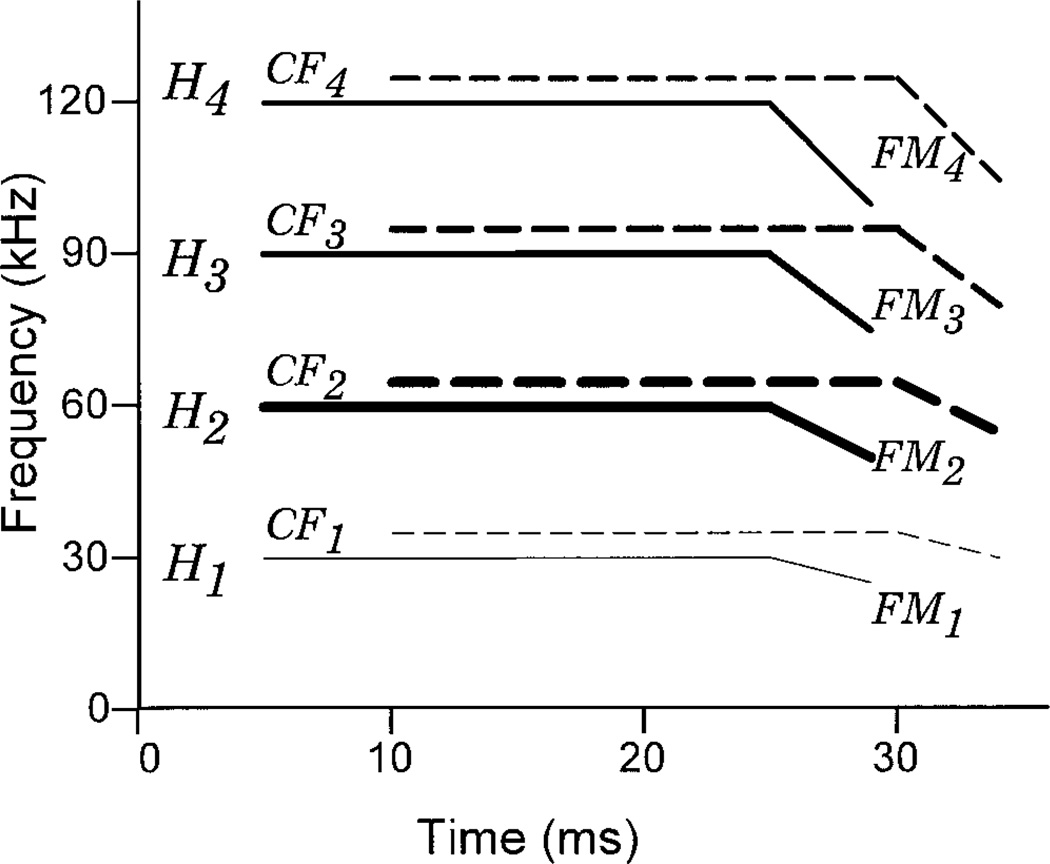

Fig. 1.

Spectrograph (idealized) of the mustached bat biosonar signal. Each sonar pulse is composed of four harmonics (H1–H4CF) composed of two main components, an initial constant frequency (CF) followed by a downward-sweeping frequency modulation (FM). H2 at about 60 kHz is dominant, followed by H3, H4, and finally the weak fundamental H1 at about 30 kHz. Duration of the components is shown for signals produced in the “search” phase of target pursuit. A Doppler-shifted, delayed echo is also shown for a single ideal target about 85 cm from the bat (dashed lines).

In a previous article (Gordon and O’Neill, 1998) we described a population of FM-selective neurons in the mustached bat located in the ventral part of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv). A mechanism for creating FM rate selectivity involving inhibitory sidebands was described. Sideband inhibition has been implicated in a number of previous studies as important for FM direction selectivity (Suga, 1965b, 1973; Watanabe, 1972; Suga and Schlegel, 1973; Heil et al., 1992a; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Fuzessery, 1994; Fuzessery and Hall, 1996). We extended these results to show that the relative time delay between excitatory and inhibitory (sideband) synaptic inputs to a neuron can create spectrotemporal filter properties selective for FM rate. The filter suppresses responses to certain “unfavorable” rates of FM because these rates activate inhibition and excitation simultaneously. The filter passes responses to other “preferred” FM rates because these rates desynchronize inhibitory and excitatory inputs, rendering the inhibition ineffective.

In this article, FM direction and rate selectivity, along with some basic response properties, are described for ICXv units. To highlight the special adaptations of ICXv cells, FM selectivity is also described in cells of the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL) and central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC). The anatomical connectivity of the ICXv is also discussed, implicating it as part of an extralemniscal auditory pathway known as the “central acoustic tract” (CAT).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation

We recorded from wild-caught Jamaican or Puerto Rican Parnell’s mustached bats (Pteronotus parnelli parnelli, P. p. portoricensis). Both male and female bats were studied. The bats were housed in a large temperature- and humidity-controlled flight room and fed fortified meal-worms. All husbandry and experimental procedures were approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources (AAALAC Assurance A-3292-01).

Single-unit recording

Surgery to mount a restraining post on the skull and to access the recording sites in the brain was done under methoxyflurane anesthesia, by using techniques described previously (O’Neill, 1985). Recordings were performed on awake animals painlessly restrained in a custom stereotactic device (Schuller et al., 1986). Action potentials were recorded extracellularly from single units in the ICXv, the ICC, and NLL. Fine parylene-C-coated tungsten electrodes (Micro-Probe, Garden Grove, CA) with impedance of 1–3 M ohms and tip exposures of 12–15 µm were used for recording. A sharpened tungsten wire contacting the dura over the cerebral cortex served as an indifferent electrode. A time-amplitude window discriminator (BAK Electronics, Germantown, MD) was used to digitize unit potentials. Data were collected only if spike amplitudes were at least 3 times greater than background activity. Discrimination of single units from multi-units or evoked potentials was based on uniformity of spike shape and size. Discrimination of single units from fibers was based on spike shape and duration: units tend to have biphasic spikes of approximately 1 ms duration, whereas fibers tend to have monophasic spikes of shorter duration.

Stimulus generation and presentation

Pure tones were generated by a sine-wave generator (Wavetek 111, San Diego, CA) and then shaped and gated with a programmable electronic switch (Wilsonics BSIT, San Diego, CA) into tone bursts with linear rise-fall times of 0.5 ms. Duration of search stimulus tone bursts was 30 ms. All stimuli were presented at a repetition rate of 5/second through a 3.75-cm diameter electrostatic transducer (Polaroid, Cambridge, MA). The speaker was placed 17.5 cm from the bat’s head, contralateral to the recording site and 25° from the midline in the horizontal plane, along the acoustic axis of the pinna at 60 kHz. The frequency response of the transducer was calibrated at the position of the bat’s head with a one-quarter inch Brüel & Kjær 4135 microphone and measuring amplifier (B & K 2610), and was essentially flat over the band of frequencies used most often in our study (50–75 kHz).

FM stimuli were generated by applying a linear voltage ramp to the voltage-controlled generator (VCG) input of the waveform generator. As with pure tones, FM stimuli had rise-fall times of 0.5 ms. We used 12 kHz bandwidth FM stimuli, similar to the bandwidth of the second harmonic FM component in the bat’s sonar pulse (Fig. 1). To generate FM sweeps with different modulation rates, the stimulus duration was varied. Duration varied from 1 ms for a sweep rate of 12 kHz/ms, to 95 ms for a sweep rate of 0.18 kHz/ms.

Experimental procedure

The best excitatory frequency (BEF) was determined at minimum threshold (MT) for each unit. MT was defined as the intensity eliciting a barely noticeable response as determined audio-visually. Peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) were collected over 50 repetitions of each stimulus. Rate-intensity functions were determined with a series of 30-ms-long tones incrementing in 10-dB steps from MT to MT + 60 dB. Rate-intensity functions were considered nonmonotonic if the response peaked and then fell by 25% or more as the amplitude increased (cf. Park and Pollak, 1994). Spontaneous activity was assessed by collecting PSTHs while the stimulus was muted (maximally attenuated to −127 dB). Response latency was estimated for each unit by visual examination of a PSTH for a 30-ms pure tone stimulus at BEF and MT + 20dB. Because most units in ICXv and NLL were phasic, the delay of the peak of the response from stimulus onset (modal bin of PSTH) was taken as the response latency. The excitatory response area was approximated by measuring its quality factor, or Q20dB, defined as the BEF divided by the tuning curve bandwidth at a level of MT+20dB.

FM selectivity was examined in each unit by presenting a series of FM sweeps, centered on the BEF, at 8 sweep rates (in most cases) in both upward and downward directions. The amplitude of the FM sweeps was fixed at MT+20dB. A quantitative index to describe FM directional selectivity (DS) was calculated with the equation: DS = (U−D)/(U+D), where U and D are the responses to upward and downward FM sweeps at a given rate (Heil et al., 1992b; Phillips et al., 1985; Tian and Rauschecker, 1994). FM directional selectivity was considered to exist if the number of spikes (for 50 stimulus repetitions) was at least twice as large in one direction as the other (DS ≥ 0.33).

The pattern of FM rate preference exhibited by each unit across the 8 sweep rates used in this study was classified according to a scheme similar to that of Tian and Rauschecker (1998). Units were classified as low-pass (LP), high-pass (HP), band-pass (BP), all-pass (AP), band-reject (BR), all-reject (AR), and complex (CX). Units were considered LP or HP for a given sweep direction if the response was greatest at slower or faster rates, respectively, and fell below 75% of the maximum response at the opposite end of the rate spectrum. BP units showed a peak of response at an intermediate rate, flanked by decline below 75% of the maximum. AP units fired well to all rates and never showed a decline below 75% of the maximal response. BR units had a dip in response at intermediate rates that was below 75% of the maximal response on either side of the dip. For AR units, spike counts at all rates in a given direction were less than 10% of the maximal response seen for the opposite direction of FM. CX units had heterogeneous patterns that did not fall into any of the above categories.

Duration selectivity was examined in about one-third of isolated units. For each of these units, a series of pure tones at BEF and MT + 20dB was presented at various durations, matching the durations of FM stimuli used in this study. For most units, tones with the following durations were presented in this order: 1, 3, 5, 15, 65 ms.

Inhibitory sideband frequencies were revealed with a forward masking paradigm involving pairs of brief (2 ms) pure tones, both at MT + 20dB (in most cases). One goal of this experiment was to mimic FM responses of units by using tone pairs (Gordon and O’Neill, 1998). The duration of these tones was a compromise, approximating the essentially instantaneous duration of individual frequencies in a FM sweep, while also providing a tonal stimulus of sufficient duration to elicit good activity at BEF. The second tone (probe) was kept at the unit’s BEF while the frequency of the first tone (masker), as well as the delay between tones, was varied. A masker frequency was considered inhibitory if it caused a decrement in response to the probe tone of at least 50%. Best inhibitory frequency (BIF) was defined as the frequency of the masker that maximally suppressed response to the probe.

Histology

Stereotactically reconstructed unit locations were verified histologically in 6 of the 10 bats. A focal iontophoretic injection of WGA-HRP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, 4% sol. in pH 7.4 phosphate- buffered saline) was made at a selected site by passing 1.5 µA DC current for 1.5 minutes (Transkinetics/Midgard, St. Louis, MO) through a micropipette with a tip diameter of 8–10 µm. After a 24-hour survival time, the bat was given an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg), and then perfused intracardially with 1.25% glutaraldehyde/1% paraformaldehyde fixative. The brain was cryoprotected, frozen and cut in the transverse plane into sections 30- or 50-µm-thick.

Of the six bats examined histologically, three bats had a single injection made in the ICXv, making them particularly useful for examining the anatomical connections of this area. For one of these three bats, two interleaved sets of brain sections were reacted with diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich). One set of sections was counter-stained with cresyl violet and another set with cytochrome oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich). For the other two bats, two interleaved sets of brain sections were collected; one set was reacted with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, Sigma-Aldrich), the other with DAB. The set of sections reacted with TMB was counterstained with safranin-O, and the set reacted with DAB was counterstained with cytochrome oxidase. One of these two bats also had a third set of sections reacted with TMB only (no counterstain). The sections were mounted onto subbed slides, cleared and cover-slipped with Permount (VWR Scientific, West Chester, PA). Sections were viewed with a Nikon Labophot microscope, camera lucida drawings were made of selected sections, and photomicrographs were taken in both bright-field and polarized light illumination to visualize TMB reaction product. Cresyl violet-stained archival sections taken at similar levels in the brains of other bats were examined to help clarify the cytoarchitectural details of the ICXv not readily visible in the lightly counterstained WGA-HRP sections of the experimental bats.

RESULTS

Single units isolated along penetrations descending through the anterolateral division (ALD) of ICC had BEFs that declined progressively starting from about 62 kHz near the surface. Physiologically, the ICC-ICXv boundary was marked by an abrupt shift in BEF from 40–50 kHz back to about 62 kHz. ICXv spans roughly 300 to 400 µm in the rostrocaudal and mediolateral dimensions, and 200–300 µm in the dorsoventral dimension.

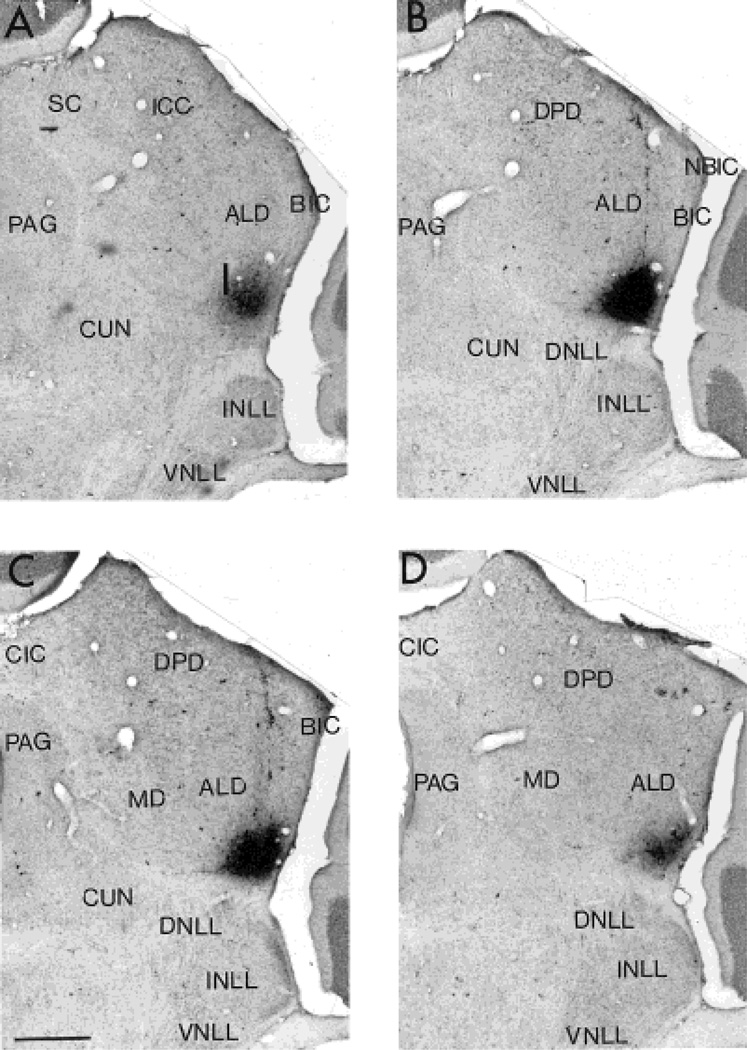

Based upon stereotactic reconstruction of electrode penetrations and WGA-HRP injection sites (Fig. 2), the region we distinguish physiologically as ICXv was located in the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICX), beneath the ALD of the central nucleus of Pteronotus’ IC. The above-mentioned abrupt transition in BEF was localized anatomically to the ALD/ICX border. Figure 3 shows the relationship of ICXv to the surrounding midbrain structures. ICXv neurons were significantly larger than those in the overlying ALD (t[348] = −1.673, P ≤ 0.03, one-tailed), and were much less densely packed. The remaining ICX (or lateral nucleus) extends rostrally beneath and lateral to the rostral pole of the ICC. The ICXv is separated from the underlying dorsal (DNLL) and intermediate (INLL) nuclei of the lateral lemniscus by the dense plexus of lemniscal fibers at the base of the IC.

Fig. 2.

Serial transverse sections of the rostral half of auditory midbrain showing the location of ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv) and its relationship to the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC anterolateral division, ALD) and the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL; intermediate nucleus, INLL; dorsal nucleus, DNLL; single focal wheatgerm agglutinin-horseradish peroxidase [WGA-HRP] injection, diaminobenzidine [DAB] reaction, cresyl violet counterstain). Sections (50-µm-thick) are arranged from rostral (A) to caudal (D) at intervals of 100 µm. Trajectories of some electrode penetrations are visible as labeled tracks above the injection site in B and C. For abbreviations in this and subsequent figures, see list. Scale bar = 500 µm.

Fig. 3.

A–D: Nissl-stained transverse sections of the rostral half of mustached bat auditory midbrain taken at the same level as those shown in Figure 2, showing the location and cytoarchitecture of the ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv). Approximate boundaries defining the surrounding divisions of the inferior colliculus (IC) and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL) are shown. Sections (60-µm-thick) are arranged from rostral (A) to caudal (D) at intervals of 120 µm. Scale bar = 200 µm.

Sixty single units were recorded from the ICXv. Response properties of ICXv units were very uniform, but often differed significantly from ICC and NLL units. The following sections and Table 1 describe these differences.

TABLE 1.

Unit Response Properties Compared Across Three Midbrain Regions: ICXv, ICC, and NLL1

| ICXv | ICC | NLL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BEF2 (kHz) | |||

| Mean ± S.E.M.5 | 62.3 ± 0.8 | 56.7 ± 2.3 | 68.3 ± 2.5 |

| Median/IQR3 | 62.5/1.6 | 58.8/13.2 | 62.9/36.4 |

| N | 60 | 22 | 89 |

| Latency (ms) | |||

| Mean ± S.E.M. | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 5.3 ± 0.1 |

| Median/IQR | 6.0/1.0 | 9.5/3.9 | 5.0/1.5 |

| N | 60 | 22 | 89 |

| Spont. rate (spikes/second) | |||

| Mean ± S.E.M. | 3.9 ± 0.83 | 10.4 ± 3.29 | 17.7 ± 2.56 |

| Median/IQR | 0.6/3.8 | 3.8/11.8 | 9.4/20.6 |

| N | 50 | 19 | 67 |

| Q20 dB | |||

| Mean ± S.E.M. | 26.3 ± 3.2 | 28.5 ± 7.3 | 16.9 ± 2.0 |

| Median/IQR | 21.1/26.0 | 13.4/31.5 | 9.9/15.6 |

| N | 58 | 20 | 83 |

| Nonmonotonic4 | 29/60 (48.3%) | 12/22 (54.5%) | 45/89 (50.6%) |

| Inhibitory sidebands4 | 30/60 (50.0%) | 2/22 (9.1%) | 1/89 (1.1%) |

ICXv, ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus; ICC, central nucleus of the inferior colliculus; NLL, nuclei of the lateral lemniscus.

BEF, best excitatory frequency.

IQR, interquartile range.

Number of units/total sample (percent of total).

S.E.M., standard error of the mean.

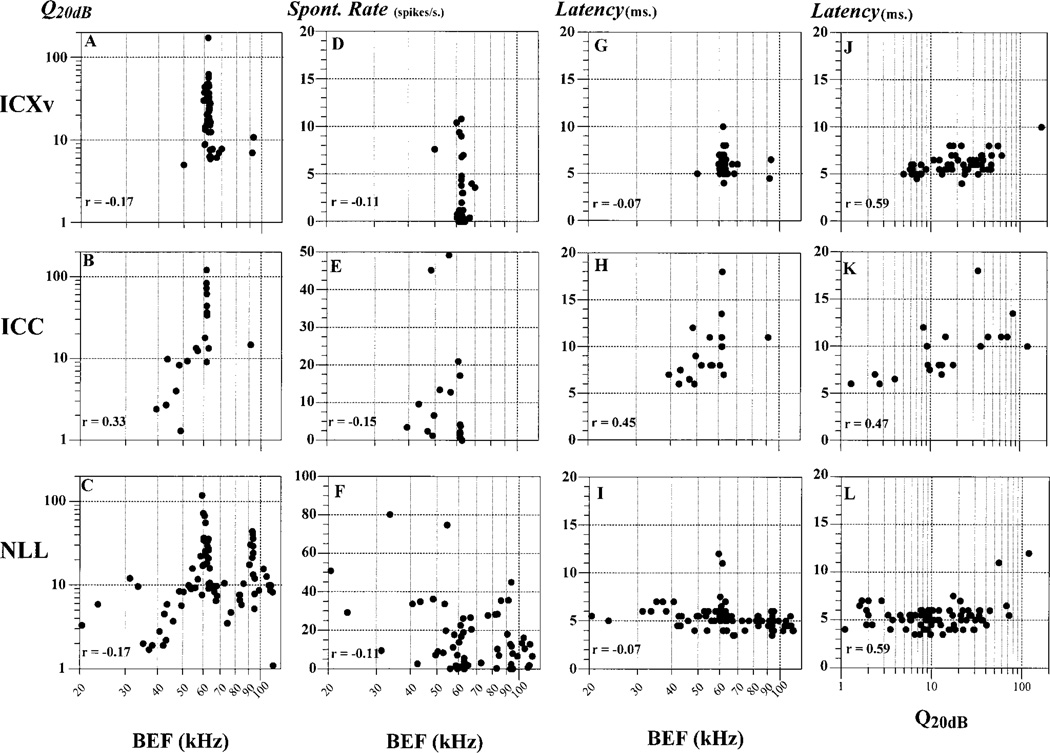

BEFs and spectral tuning properties

BEFs of units recorded in ICXv clustered at 62.3 ± 0.8 kHz (mean ± standard error; Table 1). This frequency approximates the second harmonic of the mustached bat’s biosonar signal (cf. Fig. 1), and is disproportionately represented in the auditory pathway. In the ICC, most of the units recorded were isolated in the ALD. Of 22 ICC units sampled, 9 had BEFs between 60 and 62 kHz, 11 had BEFs between 39 and 60 kHz, and 2 had BEFs of 62.7 and 91.2 kHz. Units recorded in the NLL had BEFs spanning most of the audible spectrum for the species. Based on stereotactic reconstruction, the 89 NLL units recorded were fairly evenly sampled from all three lemniscal nuclei: 22 in DNLL, 35 in INLL, and 32 in ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus (VNLL). For the purposes of this study, these units were considered collectively as “NLL units.”

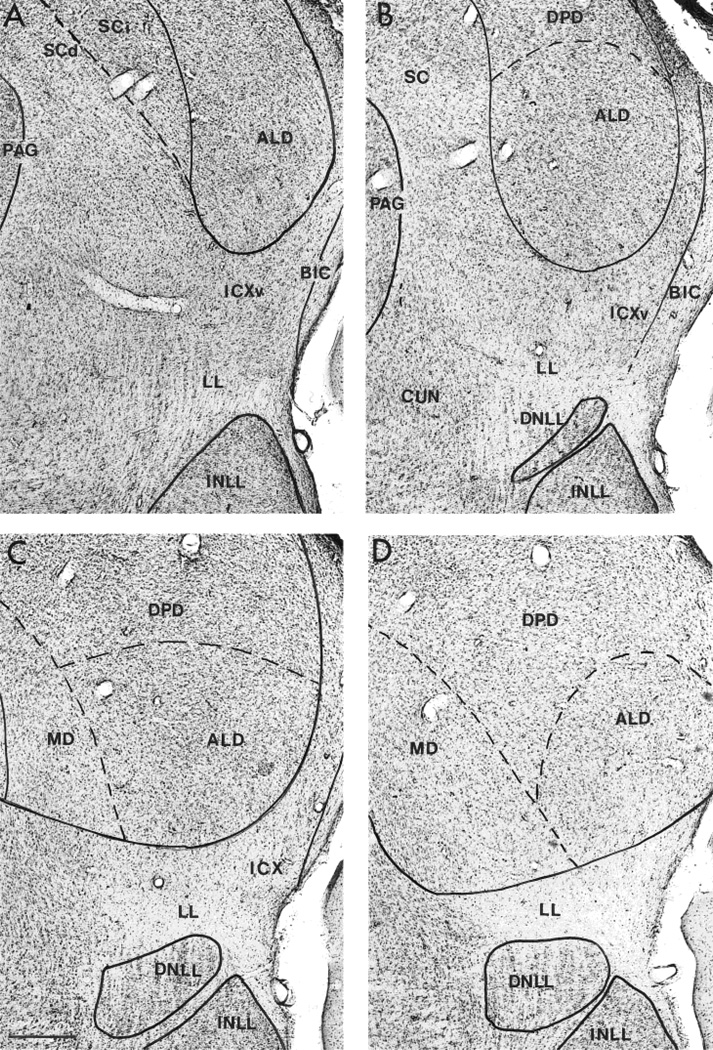

Frequency tuning curve shapes in the three areas were compared from Q20dB values (Table 1). Nonparametric comparisons of the medians showed that frequency tuning curves in the NLL were significantly broader (median Q20dB = 9.9) than in ICXv (median Q20dB = 21.1, t[139] = 3.816, P = 0.0002), but not significantly different from ICC (median Q20dB = 13.4, t[101] = −0.565, P = 0.57). No significant difference was found between ICXv and ICC (t[76] = 1.205, P = 0.23). Figure 4A–C shows the relationship between Q20dB and BEF for the three areas. Units with BEFs close to the first, second, and third harmonics of the biosonar signal (Fig. 1) were the most sharply tuned (highest Q20dB values). Q20dB values were highest at about 62 kHz (second harmonic), whereas they were particularly low (< 20) in the intervening ranges of nonbiosonar frequencies, especially between 35 and 50 kHz. ICXv units with BEFs near 62 kHz had Q20dB values mainly in the range between 10 and 100, overlapping those in the ICC (ALD) and NLL.

Fig. 4.

Basic response properties of ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv; top row), central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC; middle row), and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL; bottom row) units. Tuning curve sharpness (Q20dB; A–C), spontaneous rate (D–F), and first-spike latency (G–I) are plotted against unit best excitatory frequency (BEF). The relationship between latency and tuning sharpness (Q20dB) is shown in the rightmost column (J–L).

Spontaneous activity

Spontaneous activity was relatively high in NLL units, very low in ICXv, and intermediate in ICC (Table 1). Statistical comparison showed that spontaneous activity in both ICXv and ICC was significantly lower than in NLL (Duncan’s multiple range test, P ≤ 0.05). There was no clear relationship between spontaneous rate and BEF in any of the three areas (Fig. 4D–F).

Latency

Mean latency in ICXv (Table 1) was slightly, but significantly, longer than NLL (analysis of variance, ANOVA, F(1, 147) = 14.3347, P < 0.0002), and much shorter than ICC (F(1, 80) = 67.0321, P < 0.0001). NLL units showed a high degree of consistency for this parameter, clustering around 5 ms across all BEFs (Fig. 4I). ICXv latencies were similarly clustered between 5 and 8 ms. By contrast, ICC units showed the biggest range of latencies, as well as a stronger dependency of latency on BEF (Fig. 4H), corroborating the findings of previous studies showing an expanded latency representation in the ICC (Harris et al., 1987; Langner et al., 1987; Horikawa and Murata, 1988; Park and Pollak, 1993; Haplea et al., 1994; Saitoh and Suga, 1995; Hattori and Suga, 1997; Walton et al., 1998).

In ICC, latency showed a positive, fairly strong correlation with tuning curve sharpness (Q20dB; Fig. 4K). By contrast, ICXv and NLL units showed little variation in latency over a range of Q20dB values spanning more than two orders of magnitude.

Discharge patterns for tones and FM sweeps

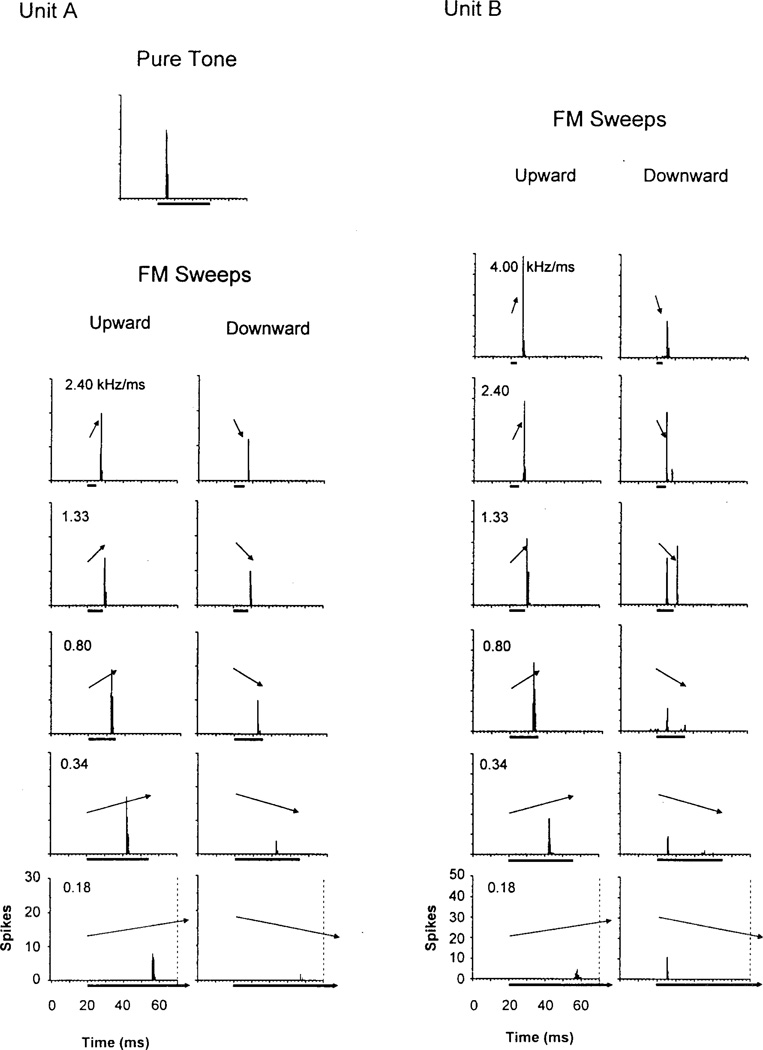

For tonal (BEF) stimuli, the temporal discharge patterns of most ICXv units were phasic (Fig. 5, top). Discharge patterns in the ICC and NLL were also predominantly phasic, but there were many tonic responses as well (particularly in DNLL and INLL). To FM sweeps, the great majority of ICXv units (47/59, 79.7%) responded with a brief, phasic-on response. The latency of this response increased as FM rate slowed and the stimulus duration lengthened (Fig. 5, Unit A). This suggests that the response was time-locked to the BEF within the FM sweep (cf. Bodenhamer et al., 1979). The remaining units (12/59, 20.3%; seven from one bat) showed a “binary” phasic response pattern, consisting of an initial phasic response time-locked to the onset transient of the sweep, and a later response time-locked to the BEF within the FM sweep. This binary response pattern was often observed only for one direction of FM (Fig. 5, Unit B, FM Sweeps, Downward). Only 3/20 ICC and 1/78 NLL units tested with FM stimuli showed a binary pattern.

Fig. 5.

Peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) for two selected units of the ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv) units from two different bats. Each PSTH represents the response to 50 repetitions of the stimulus. For the unit in A, response to a pure tone best excitatory frequency (BEF) stimulus (minimum threshold [MT] +20 dB) is shown, along with responses to a representative subset of frequency modulated (FM) stimuli. For the unit in B, only responses to FM stimuli are given. The left column displays responses to upward FM and the right column displays responses to downward FM, the rate of FM decreasing from top to bottom. Above each PSTH is a representation of the FM stimulus indicating direction and rate of FM. Below each PSTH is a bar denoting stimulus duration. Both units showed phasic response patterns to BEF tones and FM sweeps. Unit A responds to FM sweeps with a single phasic response time-locked to the BEF centered within the FM sweep. The latency shift of the response seen with longer FM stimuli is attributable to the change in timing of BEF relative to the start of the sweep. Unit A was selective for upward FM, particularly at slower rates. Unit B exhibits the less common “binary” phasic response pattern, consisting of an initial response time-locked to the onset of the sweep, and a later response time-locked to the BEF within the FM sweep, which occurs only for downward FM in this unit. The “BEF” response disappears at slower rates of downward FM, whereas the “onset” response persists.

One possible explanation for the onset response in these 16 binary units was that at stimulus onset, the initial frequency of the FM sweep was already within the excitatory response area. Binary unit excitatory response areas were relatively wide, Q20dB values averaging 9.2, much lower than the average Q value for the entire sample of units. Consequently, for 12 of the 16 binary units, the initial frequency of the FM sweep was within or just outside the border of the excitatory area at stimulus onset. Even though the initial frequency of the FM sweep was thereby near threshold for these units, the rapid amplitude modulation created by the 0.5 ms onset transient was apparently enough to elicit a response. By contrast, for the majority of more sharply tuned units showing a unitary BEF response, the initial frequency of the FM stimulus was well outside the excitatory area at stimulus onset. In this case, when the FM stimulus swept into the excitatory area, perhaps the “effective” rise-time of excitatory stimulation was longer than 0.5 ms, and hence less likely to elicit a response. Thus, a response was only elicited as the FM sweep approached BEF.

This idea was partially tested in four units by presenting BEF-centered FM stimuli with twice the original bandwidth. These units showed binary responses to 12kHz FM sweeps, but the onset response disappeared with 24-kHz FM sweeps. These sweeps started well outside the excitatory tuning curves. The FM selectivity of these units, as revealed by the BEF response, remained unchanged with the greater bandwidth stimulus.

A reasonable argument could be made to consider only the BEF response and ignore the onset response of binary units, because the vast majority of units in this study only showed a BEF response to FM stimuli. Whereas the onset responses are relatively easy to subtract out of the analysis for slower rates of FM where the two components of the response are clearly separate, it becomes difficult for faster FM stimuli where the two components coalesce (e.g., Fig. 5, unit B). We therefore chose to sum both responses for these 16 binary units to quantify their response to FM stimuli.

Inhibitory sidebands

ICXv neurons were strikingly different from both ICC and NLL in a number of other respects. The first difference involved the proportion of units with low-threshold inhibitory sidebands. Sidebands were found in half of the ICXv units, but only in a few ICC and NLL units (Table 1). As mentioned, inhibitory sidebands are a likely neuronal mechanism responsible for the high degree of FM selectivity seen in the ICXv (Gordon and O’Neill, 1998). Of the 35 inhibitory sidebands found in 30 ICXv units (some units had two sidebands), 29 were on the high frequency side of BEF. Units with high-side inhibitory sidebands are typically directionally selective for upward FM sweeps. The predominance of high-side inhibition in ICXv agrees with the upward FM preference exhibited by this population (see next section).

FM selectivity

All units (except one in ICC) showed good responses to pure tones at BEF. In general, responses to FM sweeps were about equal to pure tones (cf. Fig. 5A, Pure tone vs. FM sweeps, Upward). We use the term “FM selective” to indicate a unit that responds selectively to a certain direction or particular rates of FM, but also shows a pure tone response. Thus, at preferred FM rates, a FM selective unit responds about the same to FM signals sweeping in the preferred direction as it does to BEF tones (e.g., Fig. 5A, FM Sweeps Upward). For unfavorable FM rates, the response to FM sweeps is less than that to BEF tones (Fig. 5A, FM Sweeps Downward).

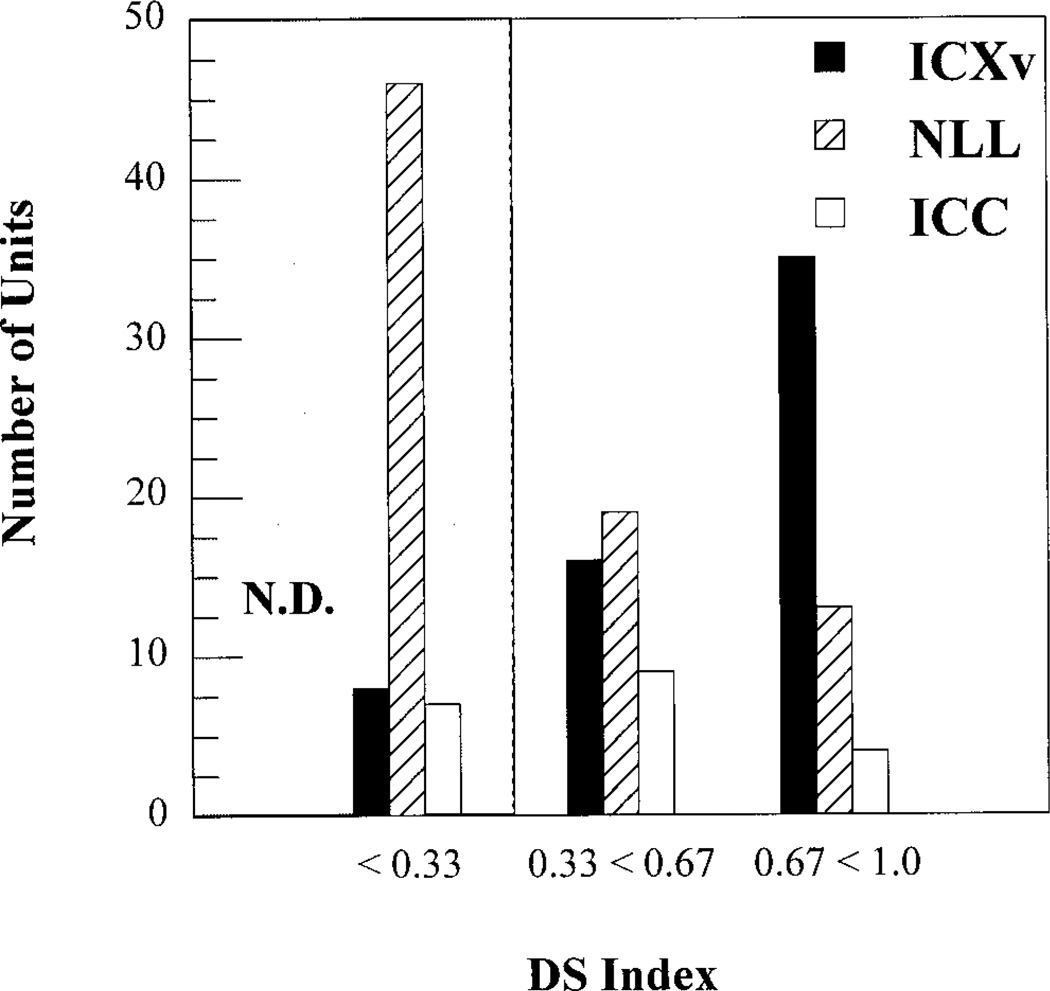

The FM selectivity of ICXv differed from ICC and NLL in a number of ways. First, the ICXv showed significantly greater directional selectivity (Fig. 6). Responses to FM sweeps were recorded in 59 of 60 ICXv units sampled. Fifty-one of these units (86.4%) were directionally selective (DS index > 0.3, i.e., two or more times greater response in one direction than the other). Moreover, there was a consistent preference for upward FM in this population: 47 units (79.7%) tested with FM preferred upward sweeps. The proportion of upward FM- preferring units was higher in the ICC and the NLL as well, but to a lesser extent than ICXv. Responses to FM sweeps were recorded in 20 of 22 ICC units. Thirteen (65%) showed significant FM directionality, and 10 (50%) preferred upward FM. Responses to FM sweeps were recorded in 78 of 89 NLL units. Thirty-four of these (43.6%) showed FM directionality and 26 (33.3%) preferred upward FM.

Fig. 6.

Frequency modulation (FM) directional selectivity indexes (DS) for units in ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv; n = 59), central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC; n = 20), and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL; n = 78). DS was calculated for each unit at that rate of FM that elicited maximal directionality. Units with DS < 0.33 were considered nondirectional (N.D.). ICXv had a higher proportion of directional units than ICC or NLL. ICXv also had the largest proportion of units with a DS value of 1.0 (indicating response to only one FM direction), and had the smallest proportion of nondirectional units, which predominated in ICC and particularly in NLL.

Second, ICXv stood out not only for its high proportion of FM selective units, but also for the degree of directional selectivity exhibited by individual units. Figure 6 displays the DS indices for units in ICXv, ICC, and NLL calculated for the rate of FM eliciting maximum directionality in each unit. Thirty-five of the 59 ICXv units tested were highly directional, with DS indices greater than 0.67, and nearly one-third (19/59, 32.2%) of ICXv units tested were fully directional (DS = 1). This means that these units responded in only one direction for at least one, and perhaps more rates. Only 1/20 (5%) ICC units and 4/78 (5.1%) NLL units tested with FM stimuli had a DS of 1.0. A much higher proportion of units were nondirectional (DS ≤ 0.33) in both ICC (7/22, 24%) and NLL (44/78, 56.4%). By contrast, only 8/59 (13.6%) ICXv units were nondirectional. Statistical analysis showed that DS indices in ICXv were significantly different from those in both the ICC and the NLL (P ≤ 0.05, Duncan’s multiple range test). By contrast, there was no significant difference between ICC and NLL.

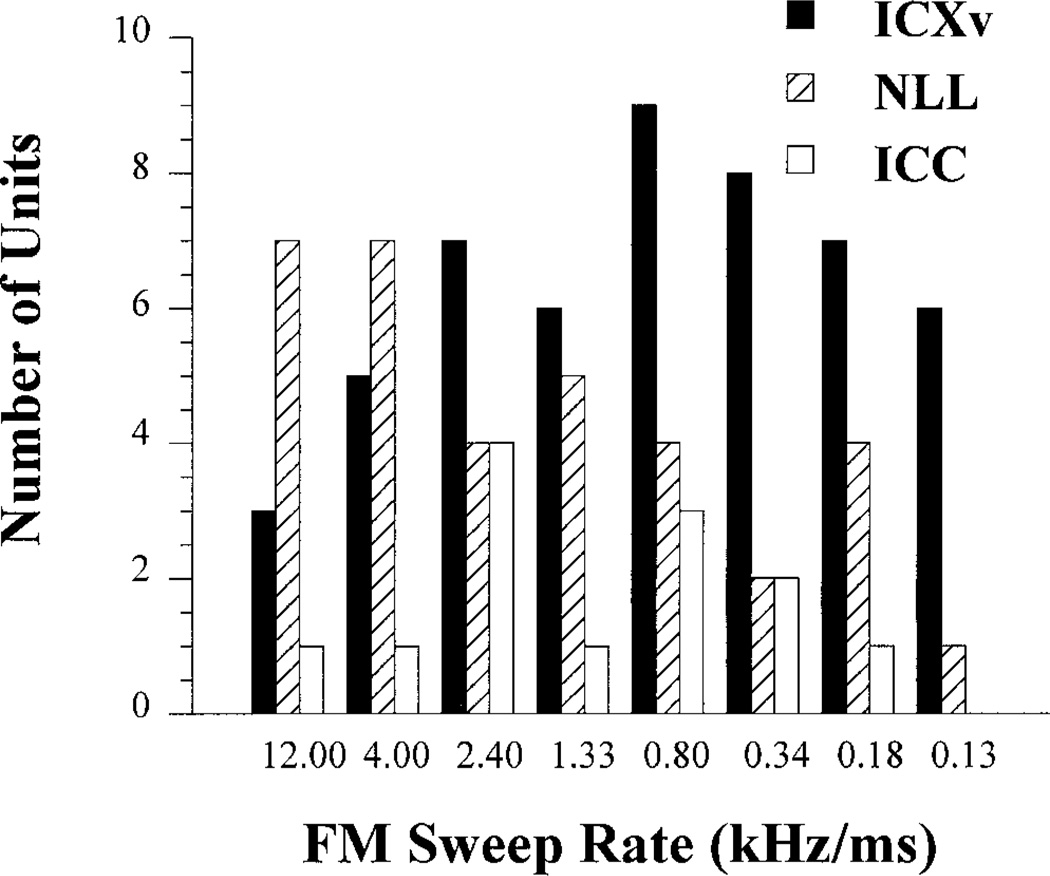

Third, ICXv units were notable for the wider range of FM rates over which they exhibited FM directionality compared to ICC and NLL units. Figure 7 shows the distribution of FM sweep rates eliciting maximum directionality in each area studied. Rates eliciting maximum directionality in ICXv units spanned a wide range, but emphasized slower rates between 0.13 and 0.80 kHz/ms. By contrast, maximum directionality was elicited by faster sweep rates in NLL, and by intermediate rates in the tested range in ICC.

Fig. 7.

Frequency modulation (FM) rates at which maximum directionality was expressed in FM selective units in ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv; n = 51), central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC; n = 13), and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL; n = 34). In ICXv, maximum FM directionality occurred at the slower FM rates more so than at the faster rates, with a peak at 0.8 kHz/ms. FM directionality peaked at faster rates for both ICC (2.4 kHz/ms) and NLL (12.0 and 4.0 kHz/ms).

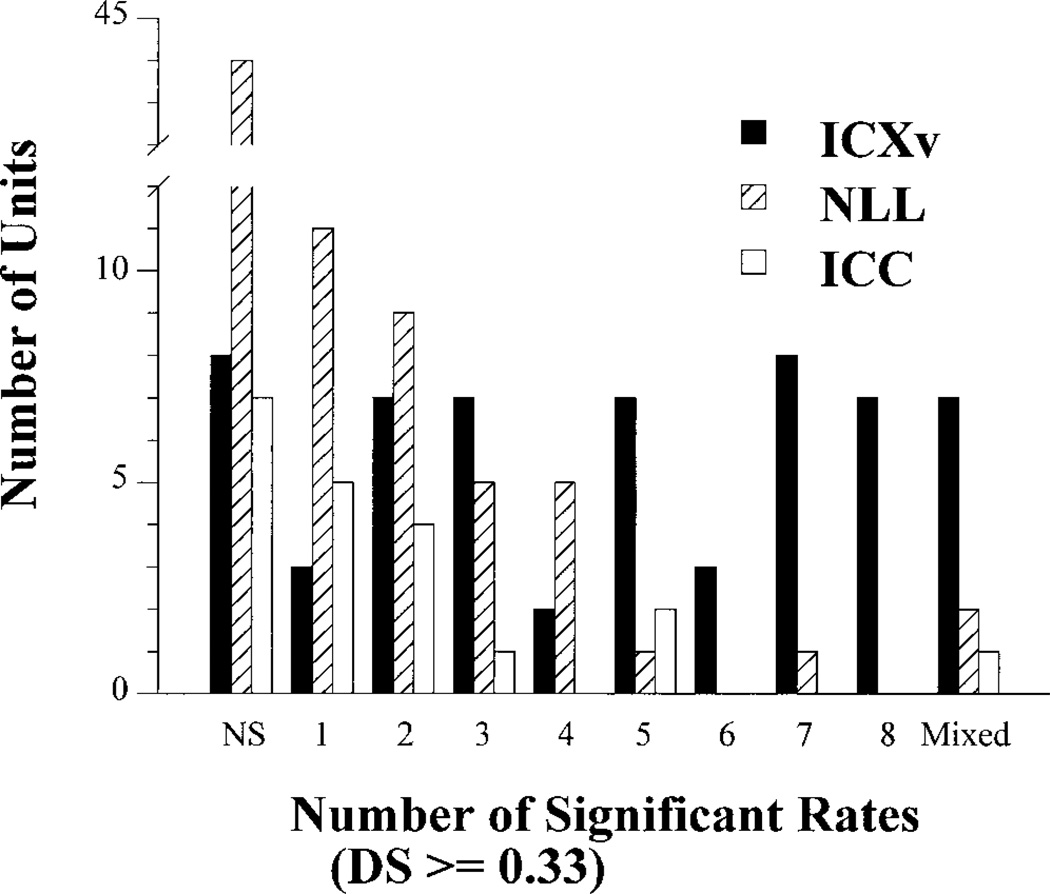

Figure 8 summarizes the number of FM sweep rates (out of the 8 rates presented) at which significant directionality was expressed in individual units of the three populations. These data show that the degree of directionality in ICXv units was less affected by rate changes than in either ICC or NLL units. Of the 59 ICXv units tested, 25 (42.4%) were directional at five or more FM rates (Fig. 8, filled bars). Only 2/20 (10%) ICC (Fig. 8, unfilled bars) and 2/78 (2.6%) NLL units (Fig. 8, crosshatched bars) were directional over this many rates.

Fig. 8.

The number of frequency modulation (FM) rates that elicited directionality (DS ≥ 0.33, 2:1 or greater) in units from external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv; n = 59), central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC; n = 20), and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL; n = 78). Units classified “NS” were nondirectional; units classified “Mixed” preferred upward FM at certain rates and downward FM at other rates. Remaining categories contain units preferring a single direction of FM. ICXv had a high proportion of units (42.4 %) with 5 to 8 rates eliciting directionality. On the other hand, most ICC and NLL units were directional at only three rates or less.

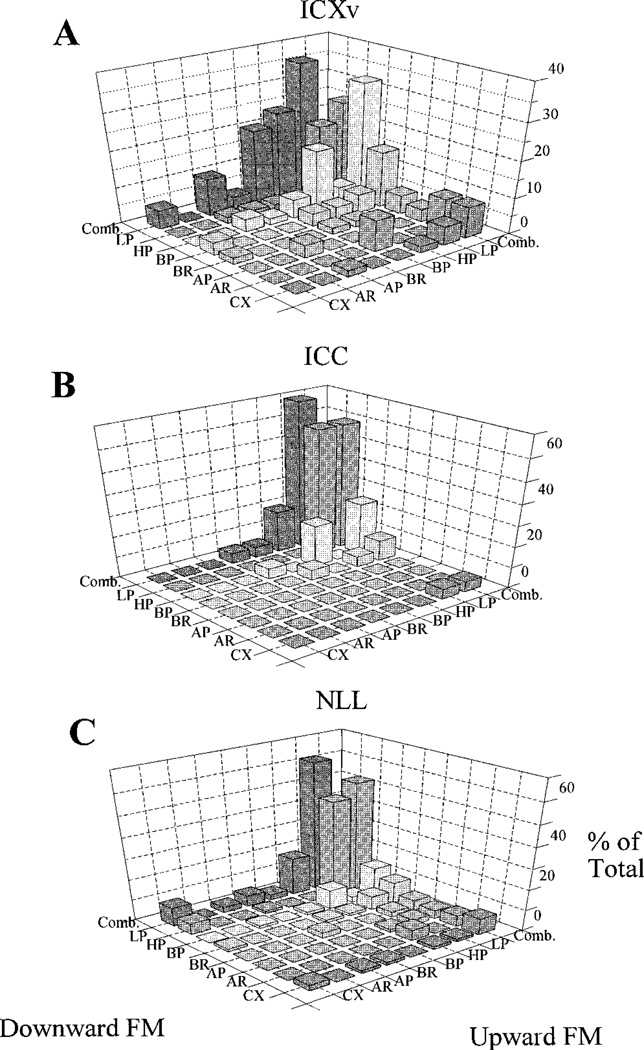

Finally, ICXv differed from ICC and NLL with regard to FM rate selectivity. Figure 9 summarizes the selectivity of units in the three areas to FM rate by categorizing each unit into a FM rate selectivity pattern (see Materials and Methods). Classification was done for both upward and downward FM stimuli for each unit. The largest FM rate preference category in each of the three areas was LP/LP (low pass down/low pass up, Fig. 9). The HP/HP (high pass/high pass) group was the second largest category. HP/HP selectivity was most pronounced in ICXv (Fig. 9A), where that category was almost as large (10/58 units, 17.2%) as the LP/LP category (12/58, 20.7%). Furthermore, if responses to downward FM are examined separately from upward responses (“Comb.” category on Upward FM axis), HP units constituted the largest unidirectional category in ICXv (19/58 units, 32.8%). By contrast, in both ICC (Fig. 9B) and NLL (Fig. 9C), LP units made up by far the largest unidirectional category for both downward and upward FM.

Fig. 9.

Patterns of frequency modulation (FM) rate selectivity seen in units from three midbrain nuclei for both upward and downward FM. A: Ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv), n = 58. B: Central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC), n = 20. C: Nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL), n = 77. Units were categorized as low-pass (LP), high-pass (HP), band-pass (BP), band-reject (BR), all-pass (AP), all-reject (AR), complex (CX; see Materials and Methods section for category criteria). The Comb. category collapsed all categories of a given FM direction, providing category totals for the opposite direction. Responses to the fastest FM rate (12.0 kHz/ms) were excluded when determining a unit’s category (see text). The LP/LP category was the largest for all three regions, probably because of a bias instilled by the confounding of FM rate and duration selectivity (see text). The second largest category in all three regions was HP/HP. This was most pronounced for ICXv, in which the HP/HP category was almost as large as the LP/LP category. For downward FM categories collapsed across all upward categories (Comb. category on Upward FM axis), HP was the largest category for ICXv units. Note that there is no category located in the rear corners of these graphs, and hence no obscured data columns there.

Because the bandwidth of our FM stimulus was kept constant, stimulus duration covaried with FM rate, faster rates being shorter. Thus, distinguishing FM rate selectivity from duration selectivity was problematic. The fastest FM stimulus (12 kHz/ms) was only 1 ms long. With rise-fall times of only 0.5 ms, such stimuli had very little spectral energy in the excitatory response area of a given unit. Therefore, such brief stimuli had little chance of eliciting much response compared to longer stimuli. Consequently, we excluded this rate from calculation of FM rate selectivity categories to avoid biasing the results toward longer/slower stimuli. Even with this exclusion, the range of FM rates used to determine rate preference categories still included a rather short duration (3 ms) stimulus.

In order to help disambiguate FM rate preference from duration preference, duration selectivity was tested directly in 55 units (33 in ICXv). Duration selectivity was tested with a set of BEF tones with durations of 1, 3, 5, 15, and 65 ms. (in most cases). Forty-seven of the 55 units (85.5%) tested for duration selectivity showed a 25% or more increase in response with increasing stimulus duration. It is thus likely that a majority of units falling into the LP/LP category show a greater response to the slower FM rates because these stimuli are simply longer in duration than faster FM stimuli. On the other hand, the high proportion of HP units in ICXv is likely a true reflection of preference for faster FM rates. Overall, only 12/55 units (21.8%) tested for duration selectivity showed a 25% or greater decline in response magnitude with increasing stimulus duration. Of the 10 ICXv units falling into the HP/HP category, six were tested for duration selectivity and only one showed a 25% or greater decline in response magnitude at longer durations.

Connections of ICXv

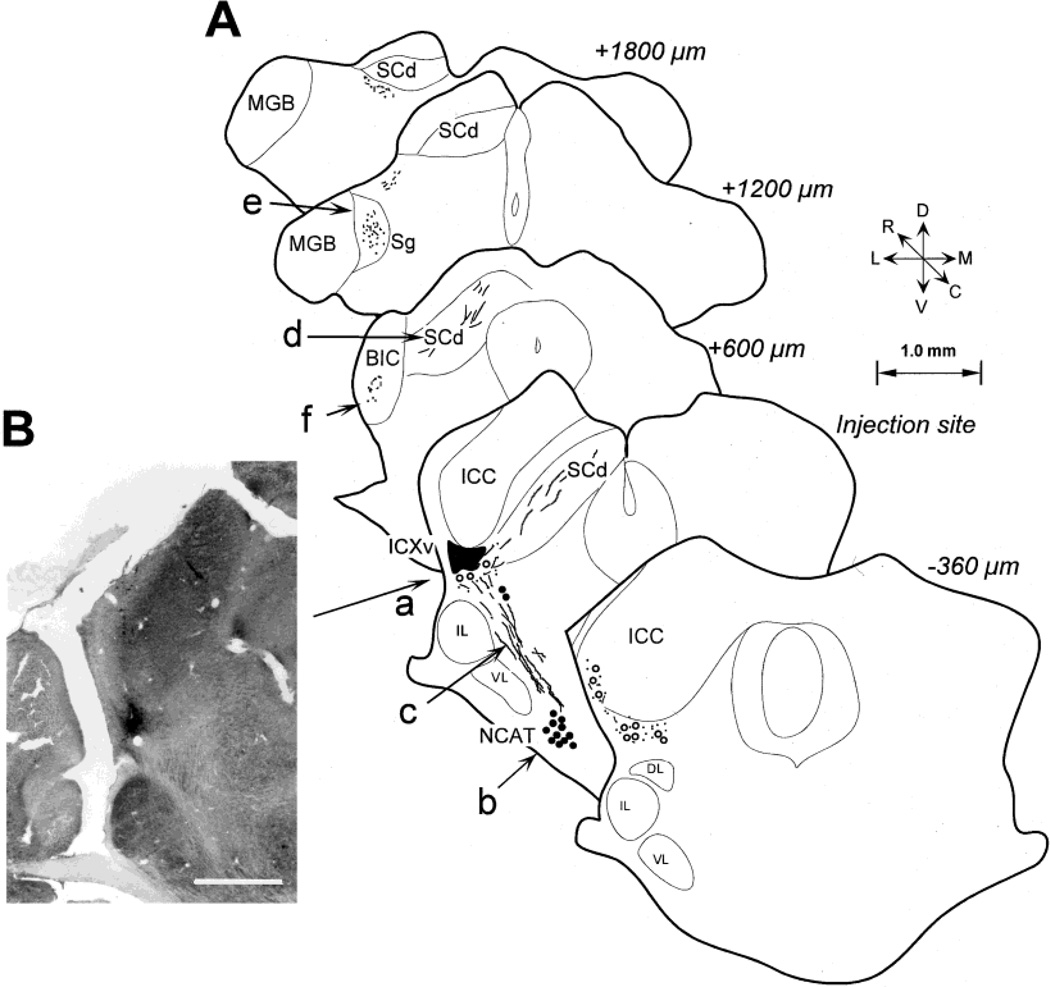

To trace the connectivity of the ICXv, focal injections of WGA-HRP were made in four bats. The tip of the micropipette was brought to the stereotaxic coordinates of previously isolated ICXv units, guided by the characteristic unit responses and the typical evoked response for this area (directional preference for upward FM sweeps, BEF ~ 62 kHz). Injections were deliberately kept quite small (about 250 µm diameter) and were well confined within the coordinates of the ICXv (e.g., Fig. 8A). A small amount of WGA-HRP may have spread into the DNLL in one case. In no case did we find evidence of labeled endings or cells in the ICC or bulk loading of tracer in labeled fibers, either of which would have indicated uptake by fibers of passage in the vicinity of the injection site.

Three bats had only one injection of WGA-HRP into the ICXv, which made them particularly useful for examining the anatomical connections of this area. Figure 10A shows the pattern of connections based on axonal transport of WGA-HRP from a single injection in the ICXv of one such bat (Fig. 10Aa, B), from which 16/60 units were recorded. There was virtually no labeling in the ICC or the NLL, which made it clear that ICXv is not directly connected to the lemniscal auditory pathway. The main target of retrograde transport was the ipsilateral nucleus of the central acoustic tract (NCAT) lying at the base of the VNLL (Fig. 10A, b). The labeled cells in the NCAT were relatively large, particularly by comparison to the dorsally adjacent cells of the VNLL. The fiber tract connecting NCAT to ICXv was strongly labeled (Fig. 10Ac). This tract lies medial to the lateral lemniscus, running somewhat closer to the rostral extent of the lateral lemniscus than the caudal extent. As predicted from the results of Casseday et al. (1989), the trajectories of some of the labeled fibers from NCAT bypassed the region of the ICXv, turning dorsomedially toward the superior colliculus (Fig. 10A). These fibers appeared to give off collaterals that projected to the ICXv, although we could not reconstruct the path of individual axons completely enough to verify this possibility.

Fig. 10.

A: Drawings depicting the connections of the ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv) determined from focal wheatgerm agglutinin-horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP) injection (filled area a) in one bat. B: Photomicrograph of diaminobenzidine (DAB)-reacted WGA-HRP-stained section (CytOx counterstained) showing the size of the injection site. In A, labeling is shown on five transverse brain sections. The rostrocaudal distance between the sections is 360 µm for the two most caudal sections, and about 600 µm between the remaining rostral sections. Large filled circles represent cell bodies labeled by retrograde transport; lines and small dots represent labeled fibers or terminals, respectively. Open circles are labeled cells in the immediate vicinity of the injection site. a: Injection site in the ICXv indicated by filled area (reconstructed from DAB-stained section shown in A). b: Retrogradely labeled cell bodies in the nucleus of the central acoustic tract (NCAT; tetramethylbenzidine [TMB] reaction). c: Labeled fibers coursing medial to the lateral lemniscus. d: Fibers in the deep superior colliculus (SCd). e: Fine punctate labeling in the suprageniculate nucleus (Sg) of the medial geniculate body. f: Transport of tracer to Sg was via fibers running along the ventral half of brachium of the inferior colliculus (BIC). D, dorsal; m, medial; c, caudal; v, ventral; l, lateral; r, rostral. Scale bar in B = 500 µm.

The primary targets of anterograde transport were the deep layers of the superior colliculus (SCd) and the suprageniculate nucleus (Sg) of the dorsal division of the medial geniculate body (MGB), both ipsilaterally. There was extensive labeling of fibers in SCd, some of which showed a branching pattern (Fig. 10Ad). Terminal fields of label were not clearly visible in SCd in this material, and it is therefore not certain that the entering fibers terminate on SCd cells. Sg was identified by the relatively large and sparsely packed cell bodies typical of this nucleus. A fine, but clearly circumscribed, cloud of labeling was observed under polarized light, suggesting the presence of terminals confined to the Sg (Fig. 10Ae). The fibers connecting ICXv with Sg ran in the ventral half of the brachium of the inferior colliculus (BIC; Fig. 10Af).

DISCUSSION

The ICXv in the mustached bat differs from ICC and NLL in terms of basic response properties, cytoarchitecture, and connectivity. ICXv units generally had low spontaneous activity, sharp tuning (Q20dB values between 17 and 80), and relatively short first-spike latencies (5–7 ms.). Cells in ICXv are larger and less densely packed than those in the ICC. ICXv units were most clearly distinguished by their responsiveness to FM sweeps and by connectivity patterns that identify them with the extralemniscal auditory pathway.

FM processing in ICXv

Our results clearly show that ICXv units are highly selective to FM sounds. The vast majority of units in ICXv were directionally selective for FM, most preferring upward over downward sweeps (Fig. 5). Compared to ICC or NLL, ICXv had a higher proportion of FM selective units and a greater degree of FM selectivity. ICXv units showed much higher directional selectivity than ICC or NLL, with over 30% of units showing a DS value of one, the highest rating for this index (Fig. 6). More ICXv units preserved directional selectivity at slower rates of FM than was found in NLL or ICC (Fig. 7). The number of modulation rates over which ICXv units exhibited FM directionality was much higher than in ICC or NLL (Fig. 8). ICXv also contained a higher proportion of units showing high-pass rate selectivity, particularly for downward FM (Fig. 9).

The higher prevalence of low-threshold inhibitory sidebands in ICXv units (50%; Table 1) is also suggestive of an area specialized for FM processing. Such sidebands have been identified as a neuronal mechanism responsible for creating FM directional selectivity (Suga, 1965a; Watanabe, 1972; Suga and Schlegel, 1973; Britt and Starr, 1976; Heil et al., 1992c; Shannon-Hartman et al., 1992; Fuzessery, 1994; Fuzessery and Hall, 1996; Gordon and O’Neill, 1998). Furthermore, the location of the sidebands in ICXv reflected the consistent preference for upward FM in this population. Of the 30 units with sidebands, 29 had high-side inhibitory areas, but only six had low-side inhibition (five units had both). High-side inhibitory sidebands are associated with upward FM preference in units because they selectively inhibit response to downward FM.

Although the relationship of inhibitory sidebands relative to BEF determines a unit’s FM direction selectivity, we have shown previously that the timing of inhibitory sideband inputs relative to BEF inputs can influence selectivity to FM rate (Gordon and O’Neill, 1998). Of the ICXv units tested with the two-tone forward masking paradigm, the majority had best inhibitory delays greater than 1 ms, implying that these units had inhibitory sideband inputs with latencies longer than BEF inputs. According to our model for FM selectivity, cells with inhibitory sideband inputs delayed relative to excitatory inputs respond well to faster rates of FM, but are suppressed by slower rates (HP rate preference pattern). This model is supported by the fact that there are more HP units in ICXv than in ICC and NLL (Fig. 9) where few inhibitory sidebands were found. Furthermore, the HP pattern was most evident with downward FM. This is correlated with the observation that the majority of identified inhibitory sidebands were found only on the high-side of BEF, thereby affecting FM rate selectivity only for downward FM.

As suggested above, a consequence of FM direction and rate selectivity both being created by inhibitory sidebands is that these response properties are interrelated and should ideally be considered together. The FM rate selectivity of a unit can influence the details of FM directionality of that unit, i.e., at which FM rates is directionality strongest. Although this relationship between FM rate and direction selectivity may be clearest at the single unit level, it can be seen at the population level to some degree. The relatively large proportion of units in ICXv with HP rate preference patterns (Fig. 9A) suggests that FM directionality should be more evident at slower FM rates (which are presumably more effective at eliciting inhibition in HP units) in this population. Indeed, Figure 7 shows that a greater number of ICXv units exhibited directionality at the four slowest rates as compared to the four fastest rates used.

Other characteristics of ICXv units suggest this region is well suited to encode the spectrotemporal features of rapid FM sounds. ICXv units had short integration times, responding well to tones only 2 or 3 ms in duration. They also had low spontaneous activity, which at suprathreshold intensities translates into a high signal-to-noise ratio, thus reducing ambiguity in temporal coding. Most ICXv units were phasic, often responding with only a single spike to each stimulus (particularly for FM). The response latency of such units was reliably time-locked to the onset of BEF (low jitter). All these properties suggest a nucleus capable of accurate temporal coding (Bodenhamer et al., 1979; Covey and Casseday, 1991).

Identification of ICXv

In our work, ICXv was primarily defined functionally, based upon the characteristic response properties of its cells contrasted against those in the neighboring ICC and NLL. WGA-HRP injections into the center of this physiologically defined area showed it to be confined not to the ICC, but rather in the ventral part of ICX. The lateral subcollicular region has not been well defined in any bat species. Wenstrup et al. (1994), in an HRP study of the projections of the IC to the MGB in Pteronotus, defined a similar region ventral to the ALD as the “pericollicular tegmentum.” They noted that the HRP labeling was continuous between the pericollicular tegmentum and adjacent ICX, and was similar in form in these two areas. Thus, the pericollicular tegmentum may be part of ICX.

Given its proximity to the lemniscal nuclei, we also considered the possibility that the ICXv corresponds to the “rostral cell group” or “anterior division” of DNLL described in several studies. In the big brown bat Eptesicus fuscus, Covey (1993) found major differences between the rostral and caudal DNLL, and named the rostral area the “dorsal paralemniscal zone” (DPL). The DPL contained primarily monaural units with low spontaneous rates and phasic firing patterns, whereas the caudal DNLL contained primarily binaural units with more sustained firing patterns. The rostral cell group of DNLL projects primarily to the ipsilateral superior colliculus, whereas the caudal cell group projects bilaterally to ICC (tree shrew: Casseday et al., 1979; cat: Henkel, 1983; big brown bat: Covey and Casseday, 1986; Zhang et al., 1987; mustached bat: Covey et al., 1987; rat: Tanaka et al., 1985).

Although we did not test for binaural responses, inputs to the ICXv appear to be monaural, in that they derive from the ipsilateral NCAT (Fig. 10), which in turn receives input from the contralateral cochlear nucleus (Casseday et al., 1989). Like DPL, the ICXv projects to the superior colliculus. Lastly, the ICXv also resembles DPL in that most cells respond phasically and have low spontaneous activity (Fig. 2).

In the mustached bat, Yang et al. (1996) also found physiological and anatomical differences in the anterior and posterior DNLL. The anterior division represents only a restricted range of frequencies below 62 kHz, and most cells are phasic responders that phase-lock to sinusoidal amplitude modulation only below 100 Hz modulation rates. By contrast, the posterior division represents almost the entire range of audible frequencies, shows more sustained discharge patterns, and phase-locks to SAM up to 400–800 Hz. Each division receives afferent projections from different brainstem auditory centers.

Despite some intriguing similarities in basic response properties between the ICXv and the anterior DNLL division of Pteronotus and DPL in Eptesicus, its location rostral, lateral, and dorsal to the DNLL and paralemniscal zone (Figs. 2, 3) argues that it is not part of DNLL, nor is it homologous to DPL. In fact, the differences in response properties and connectivity clearly outweigh the similarities between the areas. For example, the unit BEFs in ICXv represent only a very narrow band of frequencies around 62 kHz, and even more importantly, the inputs to ICXv arise only from the NCAT (Fig. 10). We therefore ruled out the possibility that ICXv in Pteronotus corresponds either to the anterior division of DNLL or to a homologue of the DPL in Eptesicus.

Metzner (1996) has shown that the paralemniscal tegmentum in the horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus rouxi) receives inputs from NCAT and projects to superior colliculus, as does ICXv. The demonstration of “audio-vocal” neurons in the paralemniscal tegmentum suggests that this region is an interface between auditory inputs and motor outputs related to vocalization.

Brain regions in other mammals with locations similar to ICXv have also been described. These include the “paralemniscal zone in the lateral midbrain tegmentum” (Henkel, 1981), the “subcollicular region” (Henkel, 1983), the “subcollicular tegmentum” (Morest and Oliver, 1984), and the “intercollicular region” (Itoh et al., 1984) in cat. Henkel (1981) showed the paralemniscal zone to be connected to brain regions controlling pinna movements.

The most compelling evidence leading us to label the region of study as part of the ICX was its anatomical connectivity. Regardless of its identity or homology, the ICXv as we defined it was clearly extralemniscal: injection of tracer into ICXv led to virtually no labeling in the ICC or NLL. We did see spread of tracer into what appeared to be the adjoining ICX (Fig. 10A, caudalmost section). The ICXv projected to deep SC, a well-known target of ICX projections (Edwards et al., 1979; Van Buskirk, 1983; Druga and Syka, 1984; Thiele et al., 1996; Thornton and Withington, 1996; King et al., 1998). In their study of gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic projections to the SC in cat, Appel and Behan (1990) noted that in addition to the ICX, an area just ventral to ICX also projected to SC, analogous to our results from the mustached bat ICXv.

Along with the projection to the SC, we found that ICXv also projected ipsilaterally to the Sg nucleus of the MGB via the ventral BIC. Metzner (1996) likewise found that injection of HRP into the horseshoe bat paralemniscal tegmentum resulted in terminal-like labeling in what appeared to be the Sg, although labeling was bilateral and predominantly contralateral.

Further studies in mustached bat are needed to determine whether the region we labeled the ICXv is homologous to any one of the structures mentioned in this section. It is of course possible that the ICXv is unique to the mustached bat, perhaps related to its unusual echolocation behavior. If this brain region is indeed a part of the mustached bat ICX, it will be important to determine in future studies whether the response characteristics of its cells represent the ICX in general, or whether the ICXv is a functionally distinct subdivision of ICX. This may prove difficult, as the remaining ICX in this species is a rather thin layer of cells flanking the ICC. Recording of single units and reliable reconstruction of their location in this structure will be a challenge. The location of ICXv ventral to ICC, in contrast, made recording and identification more feasible.

The central acoustic tract (CAT)

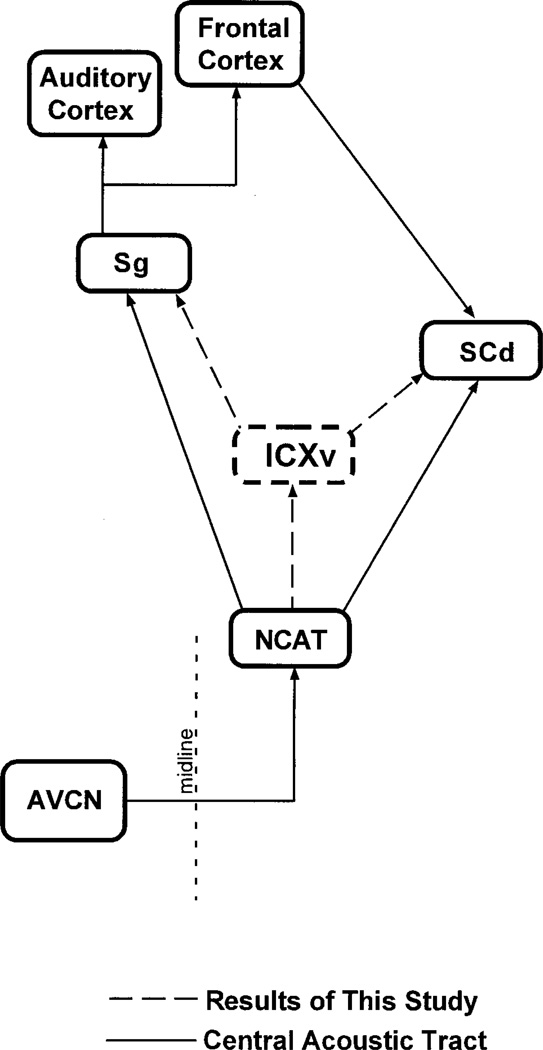

Based on its connectivity, ICXv appears to belong to an extralemniscal pathway known as the central acoustic tract (CAT). This pathway in the auditory system was first noted by Ramon y Cajal (1911) in mouse, and was later named the “central acoustic tract” by Papez (1929), who identified it in human and cat. As described by Casseday et al. (1989) and Kobler et al. (1987) in the mustached bat, the NCAT receives a mostly contralateral projection from the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. From the NCAT, the pathway continues ipsilaterally along fibers medial to the lateral lemniscus and projects to the deep layers of the SC and the Sg nucleus of the thalamus. The Sg in turn projects to auditory and frontal cortex.

Our findings suggest that in addition to the direct projection from NCAT to SC and Sg, there is another indirect projection from NCAT, via ICXv, to SC and Sg (Fig. 11). Such a projection is alluded to in the previous studies of CAT in mustached bat. Injection of WGA-HRP into NCAT resulted in some labeling in the ICX (Casseday et al., 1989). Large injections of tracer in the NCAT apparently resulted in some labeling in the rostral and ventralmost extent of ICC, adjacent to ICX. Casseday and colleagues attributed this labeling to the possible spread of tracer from NCAT to VNLL, which projects to ICC. It may be instead that this labeled region was in fact ICXv, which we found in the same location. Furthermore, injections of tracer into the Sg resulted in retrograde transport to the ICX (Kobler et al., 1987; Casseday et al., 1989).

Fig. 11.

Ascending connections of the central acoustic tract in the mustached bat and the relationship of the ventral division of the external nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICXv) to this pathway. SCd, deep layers of the superior colliculus; Sg, suprageniculate nucleus of the medial geniculate body. The anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) projects mainly to contralateral nucleus of the central acoustic tract (NCAT); all subsequent projections are ipsilateral.

The anterograde labeling pattern we found is essentially identical to that seen following injections of tracer directly into NCAT itself (Casseday et al., 1989). Without further experiments, we cannot rule out the possibility that some or all of the projections to SC and Sg that we found after tracer injections into ICXv are actually due to anterograde projections from retrogradely labeled NCAT. The trajectories of labeled fibers did suggest that at least some of the projections from NCAT to ICXv were via collaterals of NCAT fibers projecting to the SC. It is also possible that fibers of passage picked up tracer at the site of ICXv, but the use of WGA-HRP and the lack of any evidence of bulk filling of fibers in our material argue against this source of error. Furthermore, many lemniscal fibers projecting to ICC course through the region where ICXv is located. If tracer was being picked up by fibers of passage, there should have been at least some labeling in ICC, but we saw virtually none.

Because most research has focused on the dominant lemniscal component of the auditory system, relatively little is known about the extralemniscal pathways. Some progress, however, has been made in describing these smaller pathways. Several of the lateral tegmental pathways described by Morest (1965) in the cat are likely candidates for being the CAT. Calford and Aitkin (1983) also provided evidence for at least four distinct auditory pathways coursing through the thalamus of the cat, and it seems one of the pathways they described may have been the CAT. Injections of HRP into the medial division of MGB (which lies just ventral and medial to Sg) revealed labeled cells in the ICX and ventral ICC, perhaps corresponding to ICXv. Injections of HRP into Sg resulted in labeled cells in deep layers of SC and the interstitial nucleus of brachium of IC, the position of which is similar to that of ICXv.

Function of ICXv and CAT

In the cat, the ICX has been shown to contain both auditory and somatosensory units (Aitkin et al., 1978, 1981). In the barn owl, the avian analogue of the ICX (nucleus mesencephalis lateralis dorsalis, or MLD) contains a map of auditory space (Knudsen and Konishi, 1978). The MLD in turn projects to deep layers of the tectum (SC) in the barn owl, creating a bimodal auditory/ visual space map (Knudsen, 1982). The space map in ICX derives from afferents bringing in binaural information from the ICC and the superiorolivary complex. In the guinea pig, ICX projections have been shown to contribute to the formation of a space map in the SC (Thornton and Withington, 1996). Given its strong association with SC and the existence of a somatosensory component in mammals, the ICX is generally thought to be involved in the coordination of motor reflexes to auditory stimuli (head and pinna movement in response to auditory stimuli).

Behavioral lesion studies in cats (Thompson and Masterton, 1978) suggest that the extralemniscal auditory pathways lying medial to the lateral lemniscus, which probably included the CAT, are crucial for directing the initial reflexive head movement toward an unexpected sound source. By contrast, the lemniscal pathway was shown to be more important for the subsequent fine-tuning of head orientation.

Along with its apparent involvement with processing spatial information, there is accumulating evidence (including the results from this article) that ICX processes complex sounds. Units in cat ICX were found to show good responses to complex broadband sounds such as jangling keys, hand claps, “kissing” sounds, and FM sweeps (Aitkin et al., 1981). Poon et al. (1990) found that the ICX contained the largest proportion (56.5%) of FM-specialized cells in the IC of the rat. A recent study that included cat vocalizations in the stimulus set (Aitkin et al., 1994) found that 82% of cat ICX units responded more strongly to vocalizations than to pure tone or noise stimuli, compared to 27% in ICC. Some ICX units showed clear preference for one vocal stimulus over others. Units in the frontal auditory field of the mustached bat cortex, which is anatomically connected to ICXv via the Sg of the thalamus, have also recently been shown to respond well to mustached bat communication vocalizations (Kanwal et al., 2000).

The uniformly high degree of FM selectivity exhibited by ICXv units in our study suggests that the CAT is at least partially involved in FM processing. Anatomically, this notion is supported by the strong connection from Sg, which receives a projection from ICXv, to the FM-FM cortical field in mustached bat (Olsen, 1986). On the other hand, the other limb of projections from CAT to SC leads to speculation that the CAT is involved in orientation of head and pinnae toward a sound source (Kobler et al., 1987; Casseday et al., 1989). Because both the sonar signals and the communication vocalizations of Pteronotus (Kanwal et al., 1994) have prominent FM components, a dual role is certainly feasible for the CAT in echolocation and in guiding orientation behavior to communication vocalizations of conspecifics.

This possibility is supported by recent experiments showing that FM processing regions of auditory cortex previously believed to be devoted entirely to echolocation contain units that respond to communication sounds as well (Ohlemiller et al., 1996; Esser et al., 1997). Consequently, it is reasonable to postulate a functional duality for echolocation and communication sound processing in subcortical regions as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Department of Natural Resources and Environment of Puerto Rico (Permit No. 95-18); the El Verde Field Station of the University of Puerto Rico; and Dr. Armando Rodriguez-Duran for invaluable help with the collection and export of the mustached bats used in our research. The authors thank J.P. Walton, R.D. Frisina, J. Ison, and M.L. Zettel for critical comments on the manuscript, and J. Housel for help with figures. Grant sponsors: PHS/NIH National Institute of Mental Health 1-F31-MH11059 (NRSA to M. Gordon), and National Institute of Deafness and Other Communicative Disorders 1-R01-DC3717 (W.E. O’Neill).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALD

anterolateral division of ICC

- AVCN

anteroventral cochlear nucleus

- BEF

best excitatory frequency

- BIC

brachium of IC

- BIF

best inhibitory frequency

- CAT

central acoustic tract

- CF

constant frequency

- CIC

commissure of the IC

- CUN

cuneiform nucleus

- DAB

diaminobenzidine

- DNLL (DL)

dorsal nucleus of the LL

- DPD (DP)

dorsoposterior division of ICC

- DS

directional selectivity index

- FM

frequency modulation

- H1–H4

four harmonics of the mustached bat sonar pulse

- IC

inferior colliculus

- ICC

central nucleus of IC

- ICX

external (or lateral) nucleus of IC

- ICXv

ventral division of the ICX

- INLL (IL)

intermediate nucleus of the LL

- LL

lateral lemniscus

- MD

medial division of ICC

- MGB

medial geniculate body

- MT

minimum threshold

- NBIC

nucleus of the BIC

- NCAT

nucleus of the CAT

- NLL

nuclei of the lateral lemniscus

- PAG

periaqueductal gray

- PSTH

peristimulus time histogram

- Q20dB

quality factor = BEF ÷ excitatory tuning curve bandwidth 20 dB above MT

- SC

superior colliculus

- SCd

deep layer of the SC

- SCi

intermediate layer of the SC

- Sg

suprageniculate nucleus of the MGB

- TMB

tetramethylbenzidine

- VNLL (VL)

ventral nucleus of the LL

- WGA-HRP

wheatgerm agglutinin-horseradish peroxidase

LITERATURE CITED

- Aitkin L, Tran L, Syka J. The responses of neurons in subdivisions of the inferior colliculus of cats to tonal, noise and vocal stimuli. Exp Brain Res. 1994;98:53–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00229109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Dickhaus H, Schult W, Zimmerman M. External nucleus of inferior colliculus: Auditory and spinal somatosensory afferents and their interactions. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:837–847. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Kenyon CE, Philpott P. The representation of the auditory and somatosensory systems in the external nucleus of the cat inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1981;196:25–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.901960104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appell PP, Behan M. Sources of subcortical GABAergic projections to the superior colliculus in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:143–158. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhamer R, Pollak GD, Marsh DS. Coding of fine frequency information by echoranging neurons in the inferior colliculus of the Mexican free-tailed bat. Brain Res. 1979;171:530–535. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)91057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt R, Starr A. Synaptic events and discharge patterns of cochlear nucleus cells. II. Frequency modulated tones. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:179–194. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahlander DA, McCue JJG, Webster FA. The determination of distance by echolocating bats. Nature. 1965;201:544–546. doi: 10.1038/201544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB, Aitkin LM. Ascending projections to the medial geniculate body of the cat: evidence for multiple, parallel auditory pathways through thalamus. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2365–2380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-11-02365.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casseday JH, Jones DR, Diamond ST. Projections from cortex to tectum in the tree shrew, Tupaia glis . J Comp Neurol. 1979;185:253–292. doi: 10.1002/cne.901850204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casseday JH, Kobler JB, Isbey SF, Covey E. Central acoustic tract in an echolocating bat: an extralemniscal auditory pathway to the thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1989;287:247–259. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey E. Response properties of single units in the dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus and paralemniscal zone of an echolocating bat. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:842–859. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey E, Casseday JH. Connectional basis for frequency representation in the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus of the bat Eptesicus fuscus . J Neurosci. 1986;6:2926–2940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-10-02926.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey E, Casseday JH. The monaural nuclei of the lateral lemniscus in an echolocating bat: parallel pathways for analyzing temporal features of sound. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3456–3470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03456.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey E, Hall WC, Kobler JB. Subcortical connections of the superior colliculus in the mustache bat, Pteronotus parnellii . J Comp Neurol. 1987;263:179–197. doi: 10.1002/cne.902630203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druga R, Syka J. Projections from auditory structures to the superior colliculus in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1984;45:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SB, Ginsburgh CL, Henkel CK, Stein BE. Sources of sub-cortical projections to the superior colliculus in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1979;184:309–329. doi: 10.1002/cne.901840207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erulkar LD, Butler RA, Gerstein GL. Excitation and inhibition in cochlear nucleus. II: frequency-modulated tones. J Neurophysiol. 1968;31:537–548. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser KH, Condon CJ, Suga N, Kanwal JS. Syntax processing by auditory cortical neurons in the FM-FM area of the mustached bat Pteronotus parnellii . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14019–14024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuzessery ZM. Response selectivity for multiple dimensions of frequency sweeps in the pallid bat inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1061–1079. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.3.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuzessery ZM, Hall JC. Role of GABA in shaping frequency tuning and creating FM sweep selectivity in the inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1059–1073. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M, O’Neill WE. Temporal processing across frequency channels by FM selective auditory neurons can account for FM rate selectivity. Hearing Res. 1998;122:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haplea S, Covey E, Casseday JH. Frequency tuning and response latencies at three levels in the brainstem of the echolocating bat, Eptesicus fuscus . J Comp Physiol A. 1994;174:671–683. doi: 10.1007/BF00192716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DM, Goodman DA, Lambert DC, Kotlarz J. Latency of multiunit responses in inferior colliculus. Abstr Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 1987;10:177. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori T, Suga N. The inferior colliculus of the mustached bat has the frequency-vs.-latency coordinates. J Comp Physiol A. 1997;180:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s003590050047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Irvine DR. Functional specialization in auditory cortex: responses to frequency- modulated stimuli in the cat’s posterior auditory field. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:3041–3059. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Langner G, Scheich H. Processing of frequency-modulated stimuli in the chick auditory cortex analogue: evidence for topographic representations and possible mechanisms of rate and directional sensitivity. J Comp Physiol A. 1992a;171:583–600. doi: 10.1007/BF00194107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Rajan R, Irvine DRF. Sensitivity of neurons in cat primary auditory cortex to tones and frequency-modulated stimuli. I: effects of variation of stimulus parameters. Hearing Res. 1992b;63:108–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil P, Rajan R, Irvine DRF. Sensitivity of neurons in cat primary auditory cortex to tones and frequency-modulated stimuli. II: organization of response properties along the “isofrequency” dimension. Hearing Res. 1992c;63:135–156. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90081-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel CK. Afferent sources of a lateral midbrain tegmental zone associated with the pinnae in the cat as mapped by retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase. J Comp Neurol. 1981;203:213–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.902030205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel CK. Evidence of sub-collicular auditory projections to the medial geniculate nucleus in the cat: an autoradiographic and horseradish peroxidase study. Brain Res. 1983;259:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa J, Murata K. Spatial distribution of response latencies in the rat inferior colliculus. Proc Jpn Acad Sci. 1988;64B:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K, Kaneko T, Kudo M, Mizuno N. The intercollicular region in the cat: a possible relay in the parallel somatosensory pathways from the dorsal column nuclei to the posterior complex of the thalamus. Brain Res. 1984;308:166–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90931-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal JS, Matsumura S, Ohlemiller K, Suga N. Analysis of acoustic elements and syntax in communication sounds emitted by mustached bats. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1994;96:1229–1254. doi: 10.1121/1.410273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal JS, Peng JP, Esser K-H. Audio-vocal communication and echolocation in the mustached bat: computing dual functions with single neurons. In: Thomas J, Moss CF, Vater M, editors. Echolocation in bats and dolphins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kent RD, Read C. The acoustic analysis of speech. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- King AJ, Jiang ZD, Moore DR. Auditory brainstem projections to the ferret superior colliculus: anatomical contribution to the neural coding of sound azimuth. J Comp Neurol. 1998;390:342–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI. Auditory and visual maps of space in the optic tectum of the barn owl. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1177–1194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-09-01177.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI, Konishi M. Space and frequency are represented seper-ately in auditory midbrain of the owl. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:870–884. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.4.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobler JB, Isbey SF, Casseday JH. Auditory pathways to the frontal cortex of the mustache bat, Pteronotus parnellii . Science. 1987;236:824–826. doi: 10.1126/science.2437655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langner G, Schreiner C, Merzenich MM. Covariation of latency and temporal resolution in the inferior colliculus of the cat. Hearing Res. 1987;31:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JR, Cynader MS. Sensitivity of cat primary auditory cortex (A1) neurons to the direction and rate of frequency modulation. Brain Res. 1985;327:331–335. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91530-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JR, Schreiner CE, Sutter ML, Grasse KL. Functional topography of cat primary auditory cortex: responses to frequency-modulated sweeps. Exp Brain Res. 1993;94:65–87. doi: 10.1007/BF00230471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzner W. Anatomical basis for audio-vocal integration in echolocating horseshoe bats. J Comp Neurol. 1996;368:252–269. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960429)368:2<252::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller AR. Coding of amplitude and frequency modulated sounds in the cochlear nucleus. Acustica. 1974;31:202–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morest DK. The lateral tegmental system of the midbrain and MGB: a study with Golgi and Nauta methods in cat. J Anat. 1965;99:611–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morest DK, Oliver DL. The neuronal architecture of the inferior colliculus in the cat: defining the functional anatomy of the auditory midbrain. J Comp Neurol. 1984;222:209–236. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PG, Erulkar SD, Bryan JS. Response of units of the inferior colliculus to time-varying acoustic stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 1966;29:834–860. doi: 10.1152/jn.1966.29.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, Kanwal JS, Suga N. Facilitative responses to species-specific calls in cortical FM-FM neurons of the mustached bat. Neuroreport. 1996;7:1749–1755. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199607290-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JF. Processing of biosonar information by the medial geniculate body of the mustached bat, Pteronotus parnellii. St. Louis: Washington University; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill WE. Responses to pure tones and linear FM components of the CF-FM biosonar signal by single units in the inferior colliculus of the mustached bat. J Comp Physiol A. 1985;157:797–815. doi: 10.1007/BF01350077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papez JW. Central acoustic tract in cat and man. Anat Rec. 1929;42:60. [Google Scholar]

- Park TJ, Pollak GD. GABA shapes a topographic organization of response latency in the mustache bat inferior colliculus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:5172–5187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05172.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TJ, Pollak GD. Azimuthal receptive fields are shaped by GABAergic inhibition in the inferior colliculus of the mustache bat. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1080–1102. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.3.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DP, Mendelson JR, Cynader MS, Douglas RM. Responses of single neurones in cat auditory cortex to time-varying stimuli: frequency-modulated tones of narrow excursion. Exp Brain Res. 1985;58:443–454. doi: 10.1007/BF00235862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon PW, Chen X, Hwang JC. Basic determinants for FM responses in the inferior colliculus of rats. Exp Brain Res. 1991;83:598–606. doi: 10.1007/BF00229838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon PWF, Sun X, Kamada T, Jen P-S. Frequency and space representation in the inferior colliculus of the fm bat, Eptesicus fuscus . Exp Brain Res. 1990;79:83–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00228875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon y, Cajal S. Histologie du systeme nerveux de l’homme et des vertebres, tome II. Paris: Maloine; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh I, Suga N. Long delay lines for ranging are created by inhibition in the inferior colliculus of the mustached bat. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1–11. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller G, Radtke-Schuller S, Betz M. A stereotaxic method for small animals using experimentally determined reference profiles. J Neurosci Methods. 1986;18:339–350. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(86)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon-Hartman S, Wong D, Maekawa M. Processing of pure-tone and FM stimuli in the auditory cortex of the FM bat, Myotis lucifugus . Hearing Res. 1992;61:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90049-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N. Analysis of frequency-modulated sounds by auditory neurons of echolocating bats. J Physiol. 1965a;179:26–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga N. Functional properites of auditory neurones in the cortex of echo-locating bats. J Physiol. 1965b;181:671–700. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]