Abstract

Objective:

Maraviroc, a chemokine co-receptor type 5 (CCR5) antagonist, has demonstrated comparable efficacy and safety to efavirenz, each in combination with zidovudine/lamivudine, over 96 weeks in the Maraviroc vs. Efavirenz Regimens as Initial Therapy (MERIT) study. Here we report 5-year findings.

Design:

A randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase IIb/III study with an open-label extension phase.

Methods:

Treatment-naive patients with CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection (Trofile) received maraviroc 300 mg twice daily or efavirenz 600 mg once daily, and zidovudine/lamivudine 300 mg/150 mg twice daily. After the last patient's week 96 visit, the study was unblinded and patients could enter a nominal 3-year open-label phase. Endpoints at the 5-year nominal visit (week 240) included proportion of patients (CCR5 tropism re-confirmed by enhanced sensitivity Trofile) with viral load (plasma HIV-1 RNA) below 50 and 400 copies/ml, and change from baseline in CD4+ cell count, as well as safety.

Results:

The proportion of patients maintaining viral load below 50 copies/ml was similar between treatment arms throughout the study and at week 240 (maraviroc 50.8% vs. efavirenz 45.9%). Maraviroc-treated patients had a greater increase from baseline in mean CD4+ cell count than efavirenz-treated patients at week 240 (293 vs. 271 cells/μl, respectively). Fewer patients on maraviroc vs. efavirenz experienced treatment-related adverse events (68.9 vs. 81.7%) and discontinued as a result of any adverse event (10.6 vs. 21.3%).

Conclusion:

Maraviroc maintained similar long-term antiviral efficacy to efavirenz over 5 years in treatment-naive patients with CCR5-tropic HIV-1. Maraviroc was generally well tolerated with no unexpected safety findings or evidence of long-term safety concerns.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, efavirenz, HIV-1, long term, maraviroc, randomized controlled trial, treatment-naive

Introduction

Maraviroc (MVC) is a first-in-class chemokine co-receptor type 5 (CCR5) antagonist that binds selectively to the CCR5 receptor on host cells, thereby preventing entry of HIV-1 [1]. It is approved for twice-daily (b.i.d.) use in combination with other antiretroviral drugs in patients with CCR5-tropic (R5) HIV-1 [2,3].

The efficacy and safety of once-daily (q.d.) or b.i.d. treatment with MVC vs. efavirenz (EFV), each in combination with fixed-dose zidovudine/lamivudine (ZDV/3TC), was evaluated in the Maraviroc vs. Efavirenz Regimens as Initial Therapy (MERIT) study in treatment-naive patients with R5 HIV-1. The MVC q.d. arm of this study was discontinued following a planned interim analysis, conducted after 205 patients had completed 16 weeks of therapy, for not meeting prespecified efficacy criteria [4]. Efficacy analysis at 48 weeks demonstrated that MVC b.i.d. was not noninferior to EFV for the primary endpoint of viral load below 50 copies/ml (65.3 vs. 69.3%), with a predefined noninferiority margin of 10%. In a post-hoc re-analysis that included 614 patients with confirmed R5 virus at screening, as determined using a more sensitive tropism assay [5], the lower bound of the one-sided 97.5% confidence interval (CI) for the difference between treatment arms was above 10% for this endpoint [4]. Similar efficacy results were obtained at 96 weeks [6]. Furthermore, patients receiving MVC also had a greater increase in CD4+ cell count compared with EFV at both 48 and 96 weeks, and MVC was safe and well tolerated [4,6]. In a separate study, MVC has been shown to be well tolerated, and also to have durable efficacy in treatment-experienced patients with R5 HIV-1 [7,8].

As durability of virologic response is a critical factor in the long-term success of an antiretroviral treatment regimen, it is important to evaluate long-term efficacy outcomes in clinical studies. Long-term data also play an important role in establishing confidence in the safety of new antiretroviral therapies. Long-term clinical safety follow-up is especially warranted in the study of new agents in a class, and for MVC in particular, based on some initial concerns regarding its novel mechanism of action and the potential untoward, downstream immunologic consequences of its blocking of CCR5. As CCR5 is an important part of the human chemokine system, it was important to ensure that there was no increase in malignancies or infections with MVC treatment [7,9–13]. Furthermore, the development of another CCR5 antagonist, aplaviroc, was discontinued due to hepatotoxicity in early clinical studies [9]. With this in mind, the MERIT study was designed to include an open-label extension following unblinding after the last patient's 96-week visit. Here we report findings from the open-label phase of the MERIT study extending to 240 weeks (nominal 5-year visit).

Methods

Study design and treatment

The MERIT study was approved by the institutional review boards/independent ethics committees of each participating site. The study was conducted in compliance with the principles originating or derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with all International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and local regulatory requirements, and is listed on www.clinicaltrials.gov with identifier NCT00098293. All patients provided written informed consent. The first patient entered the study in November 2004 and recruitment was completed in April 2006.

Study design has been reported in detail elsewhere [4,6]. Briefly, in this randomized, double-blind, active-comparator multicenter, phase IIb/III study, treatment-naive patients (aged at least 16 years) with R5 HIV-1, as determined using the original Trofile assay (Monogram Biosciences, South San Francisco, California, USA), and with plasma viral load (HIV-1 RNA) above 2000 copies/ml, received MVC 300 mg q.d., MVC 300 mg b.i.d., or EFV 600 mg q.d., each in combination with ZDV/3TC 300 mg/150 mg b.i.d. Key exclusion criteria included prior treatment with EFV, ZDV, 3TC, or any antiretroviral for more than 14 days at any time, and evidence of resistance to EFV, ZDV, or 3TC, as indicated by the presence of at least one nucleoside-associated mutations conferring resistance to ZDV (including M41L, D67N, K70R, L210W, T215Y/F, and K219Q/E/N) or phenotypic resistance to ZDV, multinucleoside resistant genotype (including the Q151M complex and codon 67–69 inserts), at least one mutation conferring resistance to 3TC (including M184V/I, E44D, V118I) or phenotypic resistance to 3TC, or at least one mutation responsible for EFV resistance (including K103N, Y181C/I, Y188C/L/H, G190A/S, V106A, L100I, A98G, K101E, V108I, P225H, and M230L) or phenotypic resistance to EFV. Furthermore, patients with underlying medical conditions that could lead to reduced tolerability to study treatment [creatinine >3× the upper limit of normal (ULN), creatinine clearance <50 ml/min, bilirubin >2× ULN, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >3× ULN, liver cirrhosis, absolute neutrophil count ≤750 cells/μl, platelet count ≤50 000 cells/μl, and hemoglobin ≤7 g/dl] were excluded. Additionally, patients with any safety, behavioral, clinical, or administrative reasons that, in the investigator's judgment, would potentially compromise study compliance or the ability to evaluate safety/efficacy were excluded.

Following a planned analysis at week 16, the MVC q.d. arm was discontinued for not meeting prespecified efficacy criteria, and the study continued with two treatment arms. The sponsor was unblinded at the 48-week analysis time point, but the investigators and patients remained blinded until the 96-week analysis. The study was then fully unblinded following the last patient's 96-week visit, and patients were enrolled in a nominal 3-year open-label phase. Efficacy and safety data from the 240-week (nominal 5-year) study duration are presented for the MVC b.i.d. and EFV treatment arms in this paper.

Study assessments and statistical analysis

Blood samples (10 ml) were collected throughout the study, including at 12-weekly visits during the open-label phase, and were analyzed by a central laboratory (Covance) for plasma viral load and immunological status. Key efficacy endpoints were the proportion of patients achieving plasma viral load less than 50 and less than 400 copies/ml, and change from baseline in CD4+ cell count, as reported previously [4]. Five-year efficacy analyses of the MVC b.i.d. and EFV q.d. arms were based on the cohort of patients who received at least one dose of study medication and who were confirmed as having R5 HIV-1 infection following re-testing of screening samples using the enhanced sensitivity Trofile assay (Trofile-ES), which had replaced the original assay [5]. Efficacy data were summarized by treatment arm and by visit time point. For binary endpoints (plasma HIV-1 RNA less than 50 and less than 400 copies/ml), patients with missing data were treated as nonresponders, whereas for continuous data (CD4+ cell count change from baseline), a last observation carried forward paradigm was used. Both means and medians (and associated measures of variation) were calculated for CD4+ analyses. Prespecified subgroup analyses by screening viral load, baseline CD4+ cell count, geographic location (northern vs. southern hemisphere), and virus subtype (clade) were performed. Additional subgroup analyses were conducted based on age, sex, and race.

Safety assessments included adverse-event monitoring, laboratory evaluations, and vital signs measurement. Additionally, a retrospective identification of the following sponsor-defined long-term survival and selected endpoints was conducted: hepatic failure, myocardial infarction/cardiac ischemia, malignancies, category C AIDS-defining events, serious infectious events, and rhabdomyolysis.

Due to staggered study entry, some patients reached their week 96 visit prior to the last patient and thus had the opportunity for an open-label treatment period that was longer than the nominal 3 years. For safety analysis, all available data were included, and variables were summarized descriptively by treatment arm.

Results

Study population

Patient disposition and reasons for discontinuation through 96 weeks have been reported in detail previously [4] and are summarized in Fig. 1. In summary, of 917 patients randomized (MVC q.d. n = 177; MVC b.i.d. n = 368; EFV n = 372), 895 patients overall entered the double-blind treatment period (MVC q.d. n = 174; MVC b.i.d. n = 360; EFV n = 361). All patients treated in the MVC b.i.d. and EFV arms (n = 721 in total) were included in the safety analysis reported in this study. A total of 614 patients (MVC b.i.d. n = 311; EFV q.d. n = 303) were confirmed to have R5 HIV-1 virus only when re-tested with the more sensitive Trofile-ES assay [5], and were included in the efficacy analysis.

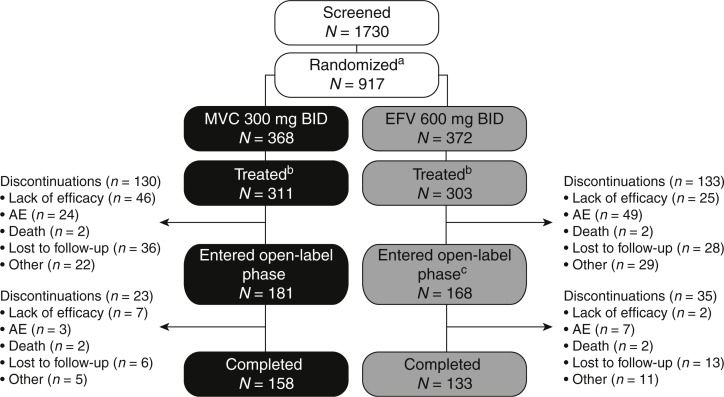

Fig. 1.

Study disposition.

aOf the 917 randomized patients, 177 patients were included in the MVC q.d. arm, which was subsequently discontinued; bpatients with confirmed R5 HIV-1 treated in the double-blind phase; ctwo patients who completed double-blind EFV treatment did not enter the open-label phase. AE, adverse event; b.i.d., twice daily; EFV, efavirenz; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MVC, maraviroc; q.d., once daily; R5, chemokine co-receptor type 5.

In the MVC treatment arm, 181 patients completed 96 weeks of blinded treatment and entered the open-label phase. In the EFV treatment arm, 170 patients completed 96 weeks of blinded therapy, and 168 entered the open-label phase. Of those who entered the open-label phase, 23 and 35 patients in the MVC and EFV treatment arms, respectively, discontinued the study prior to the nominal 5-year visit. Consistent with observations at the 48 and 96-week analyses [4,6], more patients receiving MVC discontinued due to lack of efficacy, whereas more in the EFV treatment arm discontinued due to adverse events (Fig. 1). Reasons for virologic failure in patients receiving MVC will be the subject of a separate study. Additionally, at the week 240 time point, a higher proportion of EFV-treated patients [24/35 (69%) vs. 11/23 (48%) for the MVC group] defaulted or discontinued due to other reasons, including protocol violations (Fig. 1). This was not apparent at the week 48 and 96 time points when patients and investigators remained blinded to treatment [4,6].

Baseline demographics and characteristics of the study population were comparable between the MVC b.i.d. and EFV treatment arms: approximately 71% of patients were men and 53% were white. The mean age of patients in the MVC arm was 36.4 years (range 20–69 years), compared with 37.3 years (range 18–77 years) in the EFV arm. Mean plasma viral load was 4.9 and 4.8 log10 copies/ml at baseline for the MVC and EFV arms, respectively. The MVC treatment arm had a slightly lower mean baseline CD4+ cell count (261 cells/μl) than the EFV arm (277 cells/μl). Previous medical history, including history of nervous system or psychiatric disorders, was similar across both treatment arms.

The total duration of therapy (overall sum of each patient's duration of treatment) was 1243.3 years (median of 5.1 years per patient) in the MVC b.i.d. arm and 1204.1 years (median of 3.9 years) in the EFV q.d. arm.

Efficacy

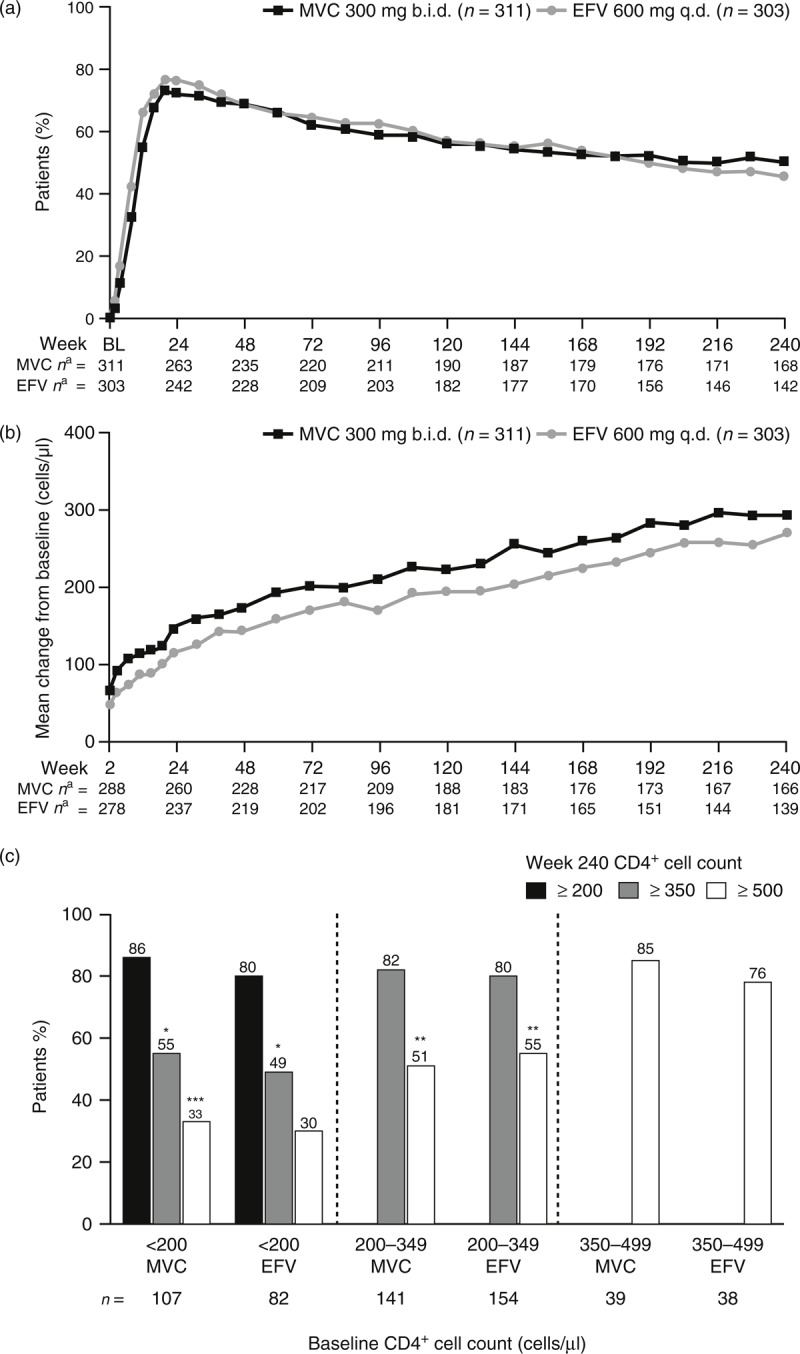

The proportions of patients with plasma viral load less than 50 copies/ml were similar throughout the study, as shown in Fig. 2a. Similar proportions of MVC and EFV recipients had plasma viral load less than 50 copies/ml at week 240 [50.8% (95% CI 45.1%, 56.5%) vs. 45.9% (95% CI 40.2%, 51.7%), respectively]. Similar results were obtained for the proportion of patients with plasma viral load below 400 copies/ml, with 52.4% (95% CI 46.7%, 58.1%) and 46.2% (95% CI 40.5%, 52.0%) of patients achieving this endpoint in the MVC and EFV treatment arms, respectively, at week 240. Subgroup analyses indicated that broadly similar proportions of patients in the various subgroups receiving MVC or EFV maintained HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/ml at week 240 (Table 1), with any differences generally mirroring the small numerical advantage seen for MVC in the overall population.

Fig. 2.

Virologic and immunologic response.

These are shown by (a) proportion of patients with HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/ml by visit, (b) mean change in CD4+ cell count by visit, and (c) shift in CD4+ cell count category from baseline to week 240 by baseline category. aNumber of patients with available data at each time point; missing data = failure for viral load and missing data imputed using last observation carried forward for CD4+ cell count. ∗Patients also included in the at least 200 cells/μl results; ∗∗patients also included in the at least 350 cells/μl results; ∗∗∗patients also included in the at least 200 and the at least 350 cells/μl results. b.i.d., twice daily; BL, baseline; EFV, efavirenz; MVC, maraviroc; q.d., once daily.

Table 1.

Proportion of patients with viral load less than 50 copies/ml at week 240 (subgroup analyses).

| MVC 300 mg b.i.d. | EFV 600 mg q.d. | |

| Total, n (%) | 158/311 (50.8) | 139/303 (45.9) |

| Screening viral load, n (%) | ||

| <100 000 copies/ml | 93/177 (52.5) | 88/183 (48.1) |

| ≥100 000 copies/ml | 65/134 (48.5) | 51/120 (42.5) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||

| Northern hemisphere | 92/164 (56.1) | 62/162 (38.3) |

| Southern hemisphere | 66/147 (44.9) | 77/141 (54.6) |

| Baseline CD4+ cell counta, n (%) | ||

| 50–100 cells/μl | 12/16 (75.0) | 2/11 (18.2) |

| 101–200 cells/μl | 38/90 (42.2) | 29/70 (41.4) |

| 201–350 cells/μl | 71/138 (51.5) | 77/161 (47.8) |

| 351–500 cells/μl | 25/41 (61.0) | 21/39 (53.9) |

| >500 cells/μl | 11/19 (57.9) | 9/18 (50.0) |

| Cladea, n (%) | ||

| Clade B | 101/176 (57.4) | 74/166 (44.6) |

| Clade C | 43/105 (41.0) | 48/99 (48.5) |

| Other | 14/29 (48.3) | 16/36 (44.4) |

| Ageb, n (%) | ||

| <45 years | 121/252 (48.0) | 108/244 (44.3) |

| 45–64 years | 36/57 (63.2) | 28/55 (50.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 119/220 (54.1) | 107/213 (50.2) |

| Female | 39/91 (42.9) | 32/90 (35.6) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 99/167 (59.3) | 76/161 (47.2) |

| Black | 45/114 (39.5) | 48/118 (40.7) |

| Other | 13/26 (50.0) | 14/21 (66.7) |

| Asian | 1/4 (25.0) | 1/3 (33.3) |

Data not shown for the following subgroups due to the low number of patients in these groups. b.i.d., twice daily; EFV, efavirenz; MVC, maraviroc; q.d., once daily.

aBaseline CD4+ cell count <50 copies/ml (n = 10) or missing (n = 1).

bClade undetermined (n = 3).

cAge ≥65 years (n = 6). Age, sex, and race subgroup analyses were not protocol-prespecified analyses.

A numerically greater proportion of week 96 responders (plasma viral load less than 50 copies/ml) maintained their response at week 240 in the MVC b.i.d. arm (n = 152/182, 83.5%; 95% CI 77.3%, 88.6%) vs. the EFV arm (n = 136/187, 72.7%; 95% CI 65.8%, 79.0%). A similar proportion of week 96 nonresponders went on to respond at week 240 in the MVC b.i.d. arm (n = 6/20, 30.0%) and EFV q.d. arm (n = 3/9, 33.3%).

At all time points throughout the study, patients receiving MVC had a higher mean increase in CD4+ cell count from baseline compared to those receiving EFV (Fig. 2b). At week 48, patients receiving MVC had a greater increase (mean and median) in CD4+ cell count from baseline [mean 173, SD 132; median 158, interquartile range (IQR) 87, 241 cells/μl], than patients in the EFV treatment arm(mean 144, SD 124, median 132, IQR 67, 207 cells/μl). Results were qualitatively the same at week 96 (MVC: mean 212, SD 152; median 188, IQR 106, 288 cells/μl and EFV: mean 170, SD 150; median 155, IQR 64, 257 cells/μl). At week 240, values were mean 293, SD 230; median 245, IQR 130, 415 cells/μl in the MVC treatment arm and mean 271, SD 230; median 245, IQR 102, 402 cells/μl in the EFV treatment arm. Shifts in CD4+ cell count category from baseline to week 240 are presented by baseline CD4+ cell count category in Fig. 2c. The MVC b.i.d. treatment arm tended to have a higher percentage of patients with shifts to higher categories than the EFV q.d. treatment arm, regardless of baseline category.

Safety

The overall proportion of patients experiencing adverse events throughout the study was comparable for the MVC (95.3%) and EFV (96.1%) treatment arms; however, fewer patients receiving MVC had adverse events that were considered to be treatment-related by the investigator (68.9 vs. 81.7%) (Table 2). Similarly, only 10.6% of MVC-treated patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events, compared with 21.3% of EFV-treated patients. The incidence of serious adverse eventss was 21.4% in the MVC arm and 22.7% in the EFV arm. Among patients receiving MVC, grade 3 and 4 adverse eventss occurred in 27.5 and 12.2%, respectively, and among patients receiving EFV, in 29.4 and 12.5%, respectively. There were eight deaths (2.2%) in the MVC arm and nine deaths (2.5%) in the EFV arm. Overall, the incidence of malignancies and Center for Disease Control (CDC) category C events was low (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of AEs, serious AEs, and CDC category C events.

| Patients, n (%) | MVC 300 mg b.i.d. (n = 360) | EFV 600 mg q.d. (n = 361) |

| All causality | ||

| AEs | 343 (95.3) | 347 (96.1) |

| Serious AEs | 77 (21.4) | 82 (22.7) |

| Grade 3 AEsa | 99 (27.5) | 106 (29.4) |

| Grade 4 AEsa | 44 (12.2) | 45 (12.5) |

| Discontinuations due to AEs | 38 (10.6) | 77 (21.3) |

| Treatment-related | ||

| AEs | 248 (68.9) | 295 (81.7) |

| Serious AEs | 12 (3.3) | 16 (4.4) |

| Discontinuations due to AEs | 19 (5.3) | 51 (14.1) |

| Dose reduced or temporary discontinuation due to AEs | 6 (1.7) | 9 (2.5) |

| Patients with CDC category C events | 11 (3.1) | 14 (3.9) |

| Infections and infestations | 9 (2.5) | 9 (2.5) |

| Neoplasms | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.4) |

AE, adverse event; b.i.d., twice daily; CDC, Center for Disease Control; EFV, efavirenz; MVC, maraviroc; q.d., once daily.

aFor Grade 3/ 4 AEs; if the same patient in a given treatment had more than one occurrence in the same preferred term event category, only the most severe (grade 4) occurrence was taken. If the same patient had two different preferred term events, one classified as grade 3 and one as grade 4, they were presented in both rows.

Nausea (MVC 38.6% vs. EFV 36.6%) was the most common adverse event in both treatment arms. Other commonly reported adverse events (≥20% of patients, either arm) included dizziness (MVC 17.2% vs. EFV 32.1%) and headache (MVC 30.3% vs. EFV 29.1%). The most commonly treatment-related adverse events (≥10% of patients, either arm) were nausea (MVC 30.8% vs. EFV 28.5%), headache (MVC 19.4% vs. EFV 18.0%), dizziness (MVC 11.9% vs. EFV 28.0%), fatigue (MVC 10.6% vs. EFV 9.1%), diarrhea (MVC 8.9% vs. EFV 14.7%), vomiting (MVC 7.8% vs. EFV 10.5%), and abnormal dreams (MVC 5.8% vs. EFV 12.5%). Dizziness, rash and pregnancy each led to the discontinuation of eight patients (2.2%) in the EFV treatment arm. Pregnancy also led to the discontinuation of eight patients (2.2%) in the MVC arm. No other adverse event resulted in the discontinuation of at least 2% of patients in this arm.

The incidence of clinically significant laboratory abnormalities (including grade 3 and 4 abnormalities) was similar for the MVC and EFV treatment arms: grade 3 or 4 adverse events of increased ALT were observed in eight patients in the MVC arm (2.2%) and five patients in the EFV arm (1.4%), and led to discontinuation of four patients in each arm. Four patients in the MVC treatment arm, and three patients in the EFV q.d. treatment arm met the criteria for Hy's law (bilirubin >2× ULN and ALT >3× ULN or AST >3× ULN) [14].

Incidences and exposure-adjusted rates of long-term survival and selected endpoints, defined based on identified potential safety issues and theoretical concerns related to the mechanism of action of MVC b.i.d., are presented in Table 3. Importantly, there was no evidence of an increased incidence of malignancies, serious infectious events, or category C AIDS-defining events with MVC vs. EFV. No patient in either the MVC b.i.d. or EFV treatment arm experienced hepatic failure; however, one patient in the discontinued MVC q.d. group developed hepatic failure that required a liver transplant. This was considered most likely to be due to hepatotoxicity by concomitantly administered isoniazid and/or co-trimoxazole, but a contributing role for MVC could not be excluded [15].

Table 3.

Summary of retrospectively identified long-term safety and other selected endpoints.

| MVC 300 mg b.i.d. (n = 360) PY = 1243.3 | EFV 600 mg q.d. (n = 361) PY = 1204.1 | |||||||

| Total events | n (%) | Raw ratea | Exposure-adjusted rateb | Total events | n (%) | Raw ratea | Exposure-adjusted rateb | |

| Any event | 50 | 38 (10.6) | 4.0 | 3.3 | 62 | 45 (12.5) | 5.1 | 4.0 |

| Hepatic failure | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| MI/cardiac ischemia | 6 | 5 (1.4) | 0.5 | 0.4 | 6 | 6 (1.7) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Malignancies | 8 | 7 (1.9) | 0.6 | 0.6 | 14 | 13 (3.6) | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| CDC category C events | 12 | 11 (3.1) | 1.0 | 0.9 | 16 | 14 (3.9) | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Infections reported as serious AEs | 28 | 24 (6.7) | 2.3 | 2.0 | 35 | 25 (6.9) | 2.9 | 2.2 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

AE, adverse event; b.i.d., twice daily; CDC, Center for Disease Control; EFV, efavirenz; MI, myocardial infarction; MVC, maraviroc; PY, patient-years; q.d., once daily.

aTotal number of events/100 PY.

bEvents/100 PY based on time to first event.

Discussion

These data from the phase IIb/III MERIT study demonstrate that MVC b.i.d. has comparable long-term efficacy to EFV q.d. throughout 5 years of follow-up, and extend and reinforce the efficacy and safety results from this study at the 48 and 96 weeks time points [4,6].

This is the first report of the long-term safety of MVC in treatment-naive patients. Although the immunologic response in patients receiving EFV in the MERIT study is consistent with what was seen in other long-term studies with EFV (increase of 225–295 cells/μl after 3–4 years), the proportion of patients with HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/ml was relatively lower [16–18]. For example, in the randomized, controlled phase III STARTMRK (raltegravir versus efavirenz, each with tenofovir/emtricitabine) study of raltegravir compared with EFV, each in combination with tenofovir/emtricitabine, 68% of patients receiving EFV in the STARTMRK study had HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/ml at week 156 [18]. Similarly, in a study comparing rilpivirine with EFV, 61% of patients receiving EFV had HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/ml at week 192 [19]. The differences observed across studies are likely to be attributable to procedural and population differences (e.g. statistical analysis methods, and patient race and sex), as well as the different backbone nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

In both treatment-naive and experienced R5 HIV-1-infected patients, treatment with MVC consistently resulted in a greater CD4+ cell response than comparator [4,6,7,20]. These findings are consistent with a meta-analysis of CCR5 antagonist studies, indicating that patients taking a CCR5 antagonist gain more CD4+ cells than those not taking a CCR5 antagonist, independent of degree of virologic suppression [21]. The MERIT data reported in this study also demonstrated that the greater CD4+ cell increases seen in MVC-treated patients compared with EFV-treated patients at weeks 48 and 96 were maintained over longer-term follow-up out to 240 weeks, and were, therefore, unlikely to be due to short-term cell redistribution. The clinical significance of this difference is unknown.

Hypothetical concerns have been raised regarding the potential immunologic consequences of blocking the human CCR5 co-receptor [13]. These concerns were further reinforced by reports of an increased frequency of malignancies observed in patients receiving vicriviroc [11,12], another investigational CCR5 antagonist, and by reports of deleterious outcomes in patients with the CCR5 delta 32 mutation following infections with certain viruses, including West Nile and yellow fever [22–24]. On the contrary, the CCR5 delta 32 deletion has been associated with a reduced incidence of rheumatoid arthritis and delayed progression of hepatitis C [25,26]. Additionally, in HIV-infected individuals, the delta 32 deletion has been associated with reduced HIV disease progression and reduced risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and certain opportunistic infections [27–30]. The 5-year data presented here, together with the 2 and 5-year follow-up data from treatment-experienced patients in the Maraviroc versus Optimal Therapy in Viremic Antiretroviral Treatment-Experienced Patients (MOTIVATE) studies [7,8], do not reveal any excess of infections (either CDC category or other infections) or malignancies, thereby providing long-term data of blocking the CCR5 receptor.

Concerns regarding the safety of CCR5 antagonists as a class were also raised following reports of hepatotoxicity with aplaviroc [10], another investigational CCR5 antagonist, which led to the termination of its further clinical development. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that CCR5 deficiency exacerbated T-cell-mediated hepatitis in mice, further increasing concerns that hepatotoxicity may be a class effect of CCR5 antagonists [31]. However, the long-term follow-up of patients participating in the MERIT and MOTIVATE studies [7] indicates no increased risk of hepatotoxicity in patients receiving MVC over time [15]. In this study, safety data for the open-label period, and for the overall 5-year study period, were broadly comparable to the blinded period.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that, in treatment-naive patients with confirmed R5 HIV-1 infection, patients receiving MVC maintained similar virologic responses to those receiving EFV throughout the 5-year study. Additionally, patients receiving MVC had improved immunologic responses, and this advantage was maintained through week 240. Reassuringly, the data confirmed the long-term safety of MVC and did not reveal any new or emerging safety concerns.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support was provided by Lynsey Stevenson of Complete Medical Communications Limited. We thank Simon Portsmouth for his input in data interpretation and review.

All authors were involved in study conception or design, or acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. E.v.d.R. was responsible for the preparation and revision of this manuscript. All authors participated in revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version for publication.

Source of funding: This study was conducted by Pfizer Inc, and was sponsored by ViiV Healthcare.

Conflicts of interest

D.C. has acted as a consultant to, and received grant support from, Pfizer Inc and ViiV Healthcare. M.B. has received speaker fees and conference sponsorship from Abbott Laboratories and Merck Sharp & Dohme. E.D. has received nongrant research support from Achillion Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman-La Roche, Idenix Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Novelos, Pfizer Inc, Sangamo Biosciences, TaiMed Biologics, Tobira Therapeutics, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and consultancy fees, honorarium or speaker fees from Gilead Sciences, Janssen, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. N.C. has acted as a consultant to, and received grant support from Tibotec/Janssen, Gilead Sciences, and ViiV Healthcare. S.W. has received speaker/consultancy/grant fees from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. A.L. has received speaker/consultancy fees from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and ViiV Healthcare, and research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and ViiV Healthcare. M.S. has acted as a consultant to, and received grant support from, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer Inc, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and ViiV Healthcare.

J.H., R.B., and G.M. are employees of, and hold stock/stock options in, Pfizer Inc. E.v.d.R., currently an independent consultant with the Research Network, was an employee of Pfizer Global Research and Development at the time that this study was conducted, and holds stock in Pfizer Inc. P.I. declares that she has no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Correspondence to David A. Cooper Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia. Tel: +61 2 9385 0900; fax: +61 2 9385 0920; e-mail: dcooper@kirby.unsw.edu.au

References

- 1.Dorr P, Westby M, Dobbs S, Griffin P, Irvine B, Macartney M, et al. Maraviroc (UK-427857), a potent, orally bioavailable, and selective small-molecule inhibitor of chemokine receptor CCR5 with broad-spectrum antihuman immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:4721–4732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ViiV Healthcare Celsentri (maraviroc) summary of product characteristics. http://www.viivhealthcare.com/products/selzentry-celsentri.aspx# [Accessed 3 April 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ViiV Healthcare Selzentry (maraviroc) prescribing information. http://www.viivhealthcare.com/∼/media/Files/G/GlaxoSmithKline-Plc/pdfs/us_selzentry.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper DA, Heera J, Goodrich J, Tawadrous M, Saag M, DeJesus E, et al. Maraviroc versus efavirenz, both in combination with zidovudine-lamivudine, for the treatment of antiretroviral-naive subjects with CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:803–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkin TJ, Goetz MB, Leduc R, Skowron G, Su Z, Chan ES, et al. Reanalysis of coreceptor tropism in HIV-1-infected adults using a phenotypic assay with enhanced sensitivity. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:925–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sierra-Madero J, Di Perri G, Wood R, Saag M, Frank I, Craig C, et al. Efficacy and safety of maraviroc versus efavirenz, both with zidovudine/lamivudine: 96-week results from the MERIT study. HIV Clin Trials 2010; 11:125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy WD, Gulick RM, Mayer H, Fätkenheuer G, Nelson M, Heera J, et al. Two-year safety and virologic efficacy of maraviroc in treatment-experienced patients with CCR5-tropic HIV-1 infection: 96-week combined analysis of MOTIVATE 1 and 2. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 55:558–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulick R, Fätkenheuer G, Burnside R, Hardy D, Nelson M, Portsmouth S, et al. Five-year safety evaluation of maraviroc in HIV-1-infected, treatment-experienced patients. Poster TUPE029 presented at the XIX International AIDS Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 22–27 July 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasmuth JC, Rockstroh JK, Hardy WD. Drug safety evaluation of maraviroc for the treatment of HIV infection. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2012; 11:161–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols WG, Steel HM, Bonny T, Adkison K, Curtis L, Millard J, et al. Hepatotoxicity observed in clinical trials of aplaviroc (GW873140). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52:858–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulick RM, Su Z, Flexner C, Hughes MD, Skolnik PR, Wilkin TJ, et al. Phase 2 study of the safety and efficacy of vicriviroc, a CCR5 inhibitor, in HIV-1-infected, treatment-experienced patients: AIDS clinical trials group 5211. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:304–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsibris AM, Paredes R, Chadburn A, Su Z, Henrich TJ, Krambrink A, et al. Lymphoma diagnosis and plasma Epstein-Barr virus load during vicriviroc therapy: results of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5211. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:642–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry J. FDA/FCHR collaborative public meeting on long-term safety concerns associated with CCR5 antagonist development. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4283b1-02-03-FDA-draftreport.pdf [Accessed 3 April 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temple R. Hy's law: predicting serious hepatotoxicity. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006; 15:241–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayoub A, Alston S, Goodrich J, Heera J, Hoepelman AI, Lalezari J, et al. Hepatic safety and tolerability in the maraviroc clinical development program. AIDS 2010; 24:2743–2750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkin A, Pozniak AL, Morales-Ramirez J, Lupo SH, Santoscoy M, Grinsztejn B, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of rilpivirine (RPV, TMC278) in HIV type 1-infected antiretroviral-naive patients: week 192 results from a phase IIb randomized trial. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2012; 28:437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arribas JR, Pozniak AL, Gallant JE, DeJesus E, Gazzard B, Campo RE, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz compared with zidovudine/lamivudine and efavirenz in treatment-naive patients: 144-week analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47:74–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockstroh JK, Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Saag MS, Lazzarin A, Wan H, et al. Long-term treatment with raltegravir or efavirenz combined with tenofovir/emtricitabine for treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients: 156-week results from STARTMRK. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:807–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassetti I, Madruga JV, Suleiman JM, Etzel A, Zhong L, Cheng AK, et al. The safety and efficacy of tenofovir DF in combination with lamivudine and efavirenz through 6 years in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients. HIV Clin Trials 2007; 8:164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulick RM, Lalezari J, Goodrich J, Clumeck N, DeJesus E, Horban A, et al. Maraviroc for previously treated patients with R5 HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1429–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkin TJ, Ribaudo HR, Tenorio AR, Gulick RM. The relationship of CCR5 antagonists to CD4+ T-cell gain: a meta-regression of recent clinical trials in treatment-experienced HIV-infected patients. HIV Clin Trials 2010; 11:351–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glass WG, McDermott DH, Lim JK, Lekhong S, Yu SF, Frank WA, et al. CCR5 deficiency increases risk of symptomatic West Nile virus infection. J Exp Med 2006; 203:35–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim JK, Louie CY, Glaser C, Jean C, Johnson B, McDermott DH, et al. Genetic deficiency of chemokine receptor CCR5 is a strong risk factor for symptomatic West Nile virus infection: a meta-analysis of 4 cohorts in the US epidemic. J Infect Dis 2008; 197:262–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pulendran B, Miller J, Querec TD, Akondy R, Moseley N, Laur O, et al. Case of yellow fever vaccine-associated viscerotropic disease with prolonged viremia, robust adaptive immune responses, and polymorphisms in CCR5 and RANTES genes. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:500–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pokorny V, McQueen F, Yeoman S, Merriman M, Merriman A, Harrison A, et al. Evidence for negative association of the chemokine receptor CCR5 d32 polymorphism with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64:487–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goulding C, McManus R, Murphy A, MacDonald G, Barrett S, Crowe J, et al. The CCR5-delta32 mutation: impact on disease outcome in individuals with hepatitis C infection from a single source. Gut 2005; 54:1157–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Roda Husman AM, Koot M, Cornelissen M, Keet IP, Brouwer M, Broersen SM, et al. Association between CCR5 genotype and the clinical course of HIV-1 infection. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127:882–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dean M, Jacobson LP, McFarlane G, Margolick JB, Jenkins FJ, Howard OM, et al. Reduced risk of AIDS lymphoma in individuals heterozygous for the CCR5-delta32 mutation. Cancer Res 1999; 59:3561–3564 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer L, Magierowska M, Hubert JB, Mayaux MJ, Misrahi M, Le Chenadec J, et al. CCR5 delta32 deletion and reduced risk of toxoplasmosis in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. The SEROCO-HEMOCO-SEROGEST Study Groups. J Infect Dis 1999; 180:920–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashton LJ, Stewart GJ, Biti R, Law M, Cooper DA, Kaldor JM. Heterozygosity for CCR5-Delta32 but not CCR2b-64I protects against certain intracellular pathogens. HIV Med 2002; 3:91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreno C, Gustot T, Nicaise C, Quertinmont E, Nagy N, Parmentier M, et al. CCR5 deficiency exacerbates T-cell-mediated hepatitis in mice. Hepatology 2005; 42:854–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]