Abstract

Small double stranded RNAs (dsRNA) are a new class of molecules which regulate gene expression. Accumulating data suggest that some dsRNA can function as tumor suppressors. Here we report further evidence on the potential of dsRNA mediated p21 induction. Using the human renal cell carcinoma cell line A498, we found that dsRNA targeting the p21 promoter significantly induced the expression of p21 mRNA and protein levels. As a result, dsP21 transfected cells had a significant decrease in cell viability with a concomitant G1 arrest. We also observed a significant increase in apoptosis. These findings were associated with a significant decrease in survivin mRNA and protein levels. This is the first report that demonstrates dsRNA mediated gene activation in renal cell carcinoma and suggests that forced over-expression of p21 may lead to an increase in apoptosis through a survivin dependent mechanism.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, RNAa, saRNA, p21WAF1/CIP1, apoptosis, survivin/Birc5

INTRODUCTION

Small double stranded RNAs (dsRNA) are a new class of molecules which have potent effects on gene expression. They are mainly known for their ability to down-regulate gene expression by targeting specific mRNA sequences for degradation, an action which has been coined RNA interference (RNAi) 1, 2. More recently, dsRNAs have also been shown to up-regulate gene expression by targeting promoters of genes of interest in a sequence specific fashion, a phenomenon termed RNA activation (RNAa) 3. Potential therapeutic options for dsRNA are broad 4, 5. One active area of research is in the treatment of various cancers. Authors have proposed that RNAi could be used to abrogate the effects of a gain of function mutation or overexpressed gene,6 while RNAa could be used to increase the expression of tumor suppressor genes 7.

Tumorigenesis is dysregulation of the balance between cellular proliferation and programmed cell death, usually in the form of apoptosis. Cellular proliferation is under the control of the cell cycle and its various critical checkpoints that are regulated by cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) as well as cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKIs).8 The ability of CDKIs to negatively regulate progression through the cell cycle lead to their consideration as potential tumor suppressors. The p21WAF1/CIP1 (p21) gene is a CDKI with multiple actions. Induction of p21 predominantly leads to G1 and G29 as well as S-phase arrest 10. p21 may also have contradictory effects on apoptosis. While it may act in normal settings to prevent programmed cell death, there are also many studies showing that forced expression may increase apoptosis 11.

Interestingly, recent data suggests that p21 may have specific effects in renal cell carcinoma, with higher levels of p21 being associated with improved outcome in patients with localized disease.12 Although, recent reports have confirmed the potential tumor suppressor effect of dsRNA mediated p21 gene activation in different cancer cell lines, 3, 7, 13, 14 none of these reports have investigated the action of dsRNA gene activation in renal cell carcinoma. Furthermore, while two of these studies have shown an increase in both early and late apoptotic cells following dsP21 transfection, 7, 15 the mechanism by which p21 leads to apoptosis is not well defined.

SurvivinBirc5 (survivin) is a human inhibitor of apoptosis. Increased survivin levels have been associated with worse prognosis in multiple cancers 16–18. In addition, RNAi has been used to decrease survivin levels and induce apoptosis 19. p21 prevents phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma proteins leading to an accumulation of hypophosphorylated pRB-E2F complex, which may suppress survivin gene expression 20. Hence, one potential mechanism whereby forced expression of p21 leads to an increase in apoptosis would be through a survivin dependent pathway.

Therefore, the aims of this study were twofold: to examine the effect of RNAa in renal cell carcinoma, and to study the effects of dsP21 mediated p21 gene activation on apoptosis and survivin expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Double-Stranded RNA

The design of dsRNA was performed as previously described.3 Synthesis of dsRNA was performed by a commercial biotechnology company (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California). A dsRNA (dsP21) targeting the p21 promoter at position -322 relative to the transcription start site (CCA ACU CAU UCU CCA AGU A[dT][dT]) and a control dsRNA (dsCON) lacking significant homology with any other human sequences (ACU ACU GAG UGA CAG UAG A[dT][dT]) were used in this study.

Cell Culture and Transfection

The human kidney cancer cell line A-498 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was grown in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). The cell line was incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The day before transfection, cells were plated in growth medium without antibiotics in 6-well plates at a density of 30%. dsRNAs were transfected at a concentration of 50 nmol/L using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 24 hours after transfection the media was changed to antibiotic containing media. Treatments with dsRNA proceeded for 72 hours prior to cell harvest.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Using one microgram of RNA, cDNA synthesis was performed with the Reverse Transcription System with oligo (dT) primers (Promega, Madison, WI). cDNA amplification was performed by PCR using the p21 gene specific primers GCCCAGTGGACAGCGAGCAG (sense) and GCCGGCGTTTGGAGTGGTAGA (antisense). Reaction conditions included an initial denaturation step (94°C for 2 min), 26 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 20 s), annealing (58°C for 20 s), and extension (72°C for 30 s) and was followed by a final incubation at 72°C for 5 min. Amplification of GAPDH was used as an endogenous control for equal RNA loading.

Real-Time PCR was performed using the 7500 Fast Real-Time System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in conjunction with gene specific TaqMan assay kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for p21, birc5, and GAPDH. GAPDH was used as an endogenous control to normalize expression. Each sample was analyzed in quadruplicate. Relative expression and standard error were calculated by the supplied Fast 7500 Real-Time System software.

Protein isolation and Western blotting analysis

Attached cells were washed with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed by adding an extraction buffer (M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent, Pierce Biotechnology, and Rockford, IL). The resulting cell lysate was collected and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined in the supernatant fraction with protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

For Western blot analysis, protein (40 ug) was denatured under reducing conditions. Protein was separated on 7.5–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels with pre-stained protein molecular weight standards. The separated proteins were then electroblotted on 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes by voltage gradient transfer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Blots were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and washed twice with 1.0% PBS; 0.1% Tween buffer. Antibodies used in detection were anti-p21/KIP1 (C-19, 1:1000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-birc5 (D-8, 1:500) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-GAPDH mouse monoclonal (MAB-374, 1:5000) (Chemicon International-Millipore, Billerica, MA). GAPDH was used as a protein loading control. Immunodetection was followed by incubation with an anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Antigen–antibody complexes were visualized by chemi-luminescence (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was investigated using the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). 24 hours after transfection, attached cells were trypsinized and then subcultured in 96-well plates containing the transfection mixture at a concentration of 1×105 cells/ml following dilution with antibiotic containing medium. Incubation occurred for 72 hours. At end of the incubation, 20 μl of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution was added to each well. After one hour, the absorbance at 490 nm was measured on an ELISA reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc, Winooski, VT).

Analysis of DNA content by flow cytometry

Media containing the floating cell population was collected from transfected A498 cells. Subsequently, the attached cells at a concentration 1×106 cells/ml were trypsinized and combined with the detached cells. The samples were centrifuged at 2,500×g and 4°C for 5 min and washed in PBS. The pellet was gently re-suspended in 1ml of cold saline GM solution (6.1 mM glucose, 1.5 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 0.9 mM KH2PO4, 0.5 mM EDTA). The cells were fixed with 5 ml of 70% cold (−20°C) ethanol overnight. Cells were then washed once at 1500×g for 5 min in PBS with 5mM EDTA and resuspended in 1 ml of propidium iodide (PI) staining solution (30 μg/ml PI, 300μg/ml RNAse A in 1x PBS). Cells were stained for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark and subsequently filtered through 30μM nylon mesh. Analysis was performed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). 10,000 events were collected and PI intensity was analyzed using the FL2 channel for relative DNA content. Forward and side scatter gates and a doublet discrimination plot were set to include whole and individual cell populations respectively. The resulting data was analyzed to determine cell cycle distribution.

Annexin V Apoptosis Assay

Media containing the floating cell population was collected from transfected A-498 cells. Subsequently, the attached cells at a concentration 1×105 cells/ml were trypsinized and combined with the floating cells. The samples were centrifuged at 2,500×g and 4°C for 5 min and washed in PBS. Annexin V-FITC and PI staining were then carried out using the Apoptosis Detection Kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA). The cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope using a dual filter for FITC and rhodamine. Cells undergoing early apoptosis were FITC + PI −. Cells undergoing late apoptosis were FITC+ PI+. A minimum of 100 cells were counted for each group.

RESULTS

A dsRNA targeting the p21 promoter induces p21 expression in kidney cancer cells

72 hours after transfection with dsP21, mRNA and protein expression were evaluated. As shown in Figure 1A, transfection with dsP21 compared with mock and dsCON transfections readily induced the expression of the target gene p21. Furthermore, Figure 1B shows that a statistically significant (p<0.001) 6-fold induction in p21 mRNA expression occurs. The increase in p21 message was further evaluated by Western blot analysis. As can be seen in Figure 1C, the elevated levels of p21 protein strongly correlated to the increase in p21 mRNA expression.

Figure 1.

A depiction of the p21 promoter and target site is shown in part A. dsP21 induces p21 expression in renal cell carcinoma A498 cell line. Cells were plated in 6-well plates and transfected with 50 nM dsRNAs for 72 hrs. mRNA was isolated for semi-quantitative (B) and quantitative analysis (C). In part C, p21 mRNA expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and are presented as the mean +/− standard error of three independent experiments (p<.0001 Mock, dsCON vs dsP21). In addition, p21 protein levels were detected by Western blot analysis using an anti-p21 antibody (D). GAPDH levels were detected as an endogenous control.

Transfection with dsP21 inhibits kidney cancer cell proliferation

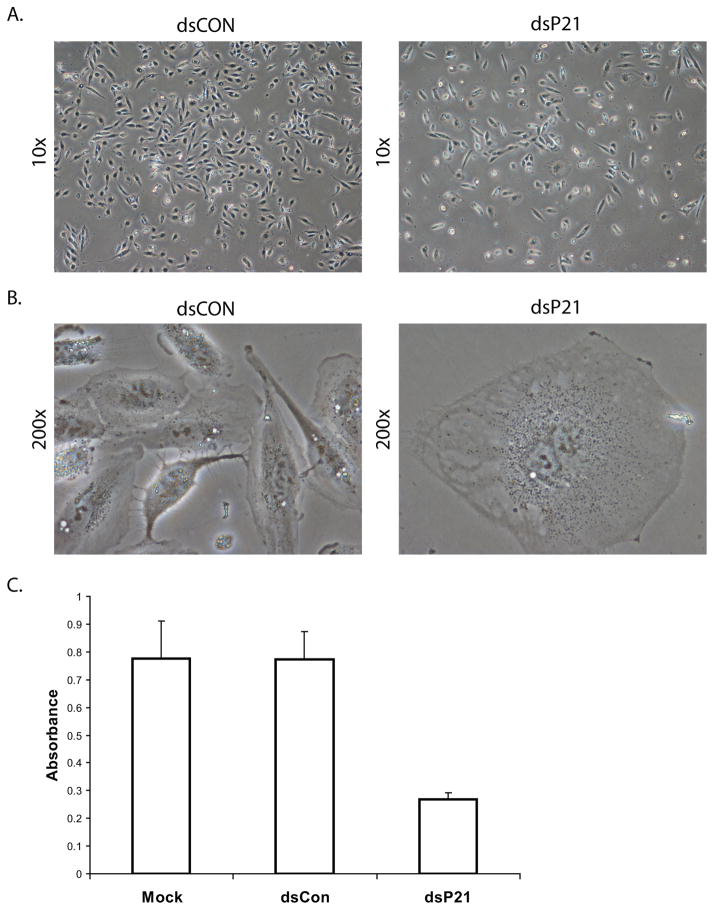

Following transfection with dsP21, a dramatic decrease in growth rate occurs so that by three days plate density is approximately 50%, compared with 100% in the mock and dsCON transfected groups. These results are shown in Figure 2A. In addition, a distinct phenotypic change occurs with the dsP21 transfected cells assuming an enlarged and flattened cellular morphology consistent with a senescent phenotype, shown in Figure 2B. Further quantitation was performed using the MTT assay. As shown in Figure 2C, at 72 hours, transfection with dsP21 was associated with a statistically significant (p=0.0004) 4-fold decrease in cell viability compared to mock or dsCON transfections.

Figure 2.

p21 promoter-targeted RNAa inhibits cell proliferation and survival. A. Cells were plated in 6-well plate format and transfected with 50 nM dsRNA. On day 3 following transfection, cells were photographed at low power 10x (A) and at high power 200x (B). Cells were also plated in 96-well plates and transfected with 50 nM dsRNA. Cell proliferation was determined on day 3 as described in Materials and Methods and plotted as the mean +/− standard error in three independent experiments (C). A statistically significant 4-fold decrease in cell viability was observed (p=.0003 Mock vs dsP21, p<.0001 dsCON vs dsP21).

Transfection with dsP21 induces G1 phase arrest and apoptosis in kidney cancer cells

The effect of p21 activation following transfection with dsP21 was examined by determining the relative DNA content of PI stained cells using flow cytometry analysis (FCA). The results of FCA can be found in Figure 3A–B. This revealed a statistically significant increase in the G1 population in dsP21 transfected A498 cells compared with mock and dsCON transfections (76% vs. 65%, p=0.01). Furthermore, a decrease in the S-phase fraction was seen (10% vs. 18%, p=0.001). No change was seen in the G2/M phase population (15% vs. 15%, p=0.43). Transfection with dsP21 also caused an increase in the sub-G0/G1 population (11% vs. 0.8%, p=0.0001) suggestive of an increase in apoptosis. Subsequently, this increase in apoptosis after dsP21 transfection was confirmed by Annexin V staining. An increase in both early apoptosis (9% vs. 1%, p<0.001) and late apoptosis (12% vs. 1%, p<0.001) were seen. A representative sample set is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Effect of p21 saRNA on the cell cycle distribution of kidney cancer cells. A498 cells were treated with mock, dsCON, and dsP21 for 72 hrs. The DNA content of PI stained cells was determined by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. Part A shows a histogram from a representative example of each of the different transfection groups. In part B the percentages of cells in the G0/G1, S, G2/M phases were calculated and are plotted as the mean +/− standard error of three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

dsP21 treatment in A498 renal cell carcinoma cell line induced apoptosis which was detected by double-staining method with FITC-conjugated Annexin V and PI using fluorescence microscopy. Annexin V stained cells indicates early apoptosis, whereas Annexin V and PI stained cells indicate late apoptosis. Representative slides from three independent experiements are shown for mock transfection (A,D), dsCon transfection (B,E), and dsP21 transfection (C,F). In part G a statistically significant 9 and 12 fold increase in staining were seen in the dsP21 transfected groups (p<.0001 Mock, dsCON vs dsP21).

Following transfection with dsP21 a decrease in survivin expression is seen

The effect of p21 activation on survivin message and protein were examined by real time PCR and Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 5, transfection with dsP21 compared with mock was associated with a nearly 8-fold decrease in survivin message which was statistically significant (p<0.02). Although a decrease in survivin levels was also seen with dsCON transfection compared to mock, this was not statistically significant (p=0.51). The decrease in survivin message was further evaluated by Western blot analysis. As can be seen in Figure 5B, forced activation of p21 strongly correlated to a decrease in survivin protein compared with both mock and dsCON transfection.

Figure 5.

dsP21 transfection is associated with a decrease in survivin expression in renal cell carcinoma A498 cell line. Cells were plated in 6-well plates and transfected with 50 nM dsRNAs for 72 hrs. mRNA was isolated for quantitative analysis (A). Survivin mRNA expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and are presented as the mean +/− standard error of three independent experiments. An 8-fold reduction in survivin message was seen following dsP21 transfection (p<.01 Mock, dsCON vs dsP21) In addition, survivin protein levels were detected by Western blot analysis using an anti-survivin antibody (B). GAPDH levels were detected as an endogenous control.

DISCUSSION

Small dsRNA mediated gene regulation is a promising new area for the treatment of many diseases and is currently in clinical trials in diseases of the eye and lung in the form of RNAi 21. However, while the specificity and high efficacy of RNAi are advantageous, this method is somewhat limited as a therapeutic to disease states with gain of function mutations or increase in copy number. In this regard, RNAa offers options for the many tumors with dysregulated tumor suppressor genes. Two studies have confirmed that RNAa can be used in bladder cancer cell lines to disrupt tumor phenotype and growth rate 7, 15. The purpose of this study was to examine whether these findings were applicable to other types of cancer, in particular renal cell carcinoma, and to expand upon the mechanism by which increased p21 expression leads to cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis.

Previous results have shown that dsRNA mediated gene activation takes place between 48 and 72 hours after transfection and that upregulation of target genes last for almost 2 weeks 3. Furthermore, prior experiments demonstrate that the effects of dsRNA activation are not related to dsRNA protein kinase activation or a non-specific interferon response 3. However, a differential susceptibility to RNAa by cell line and target gene of interest has been observed 3. The present study showed for the first time that RNAa is successful in human renal cell carcinoma. More specifically, the A498 kidney cancer cell line is susceptible to a dsP21 mediated increase in p21 mRNA and protein expression. In fact, the 6-fold induction in p21 mRNA expression is quite robust in comparison with results of other RNAa experiments.

Furthermore, transfection with dsP21 and subsequent induction of p21 protein expression led to a significant decrease in A498 cell viability and the assumption of a senescent phenotype. Similar results have been shown for ectopic expression of p21 or induction of p21 by different mechanisms 22–27. Concomitantly, results of flow cytometry showed that dsP21 transfection caused a G1 arrest, with a significant decrease in S-phase. This is a somewhat expected result given the role of p21 as a CDKI, and in particular CKD4, which is a main regulator of cell cycle progression through G1. However, these findings highlight the potent effects that can be mediated through RNAa of tumor suppressor genes.

Although previously observed, the findings of a significant number of floating cells as well as cells which assume a senescent phenotype continues to be a somewhat unexpected result of forced p21 expression. The role of p21 in apoptosis is controversial, with many studies showing the contradictory findings of both promotion and inhibition of apoptosis 11. What seems clear is that the effects of p21 vary depending on cell line 28, 29, p53 status30, and cause of p21 activation 31. In general, direct targeting of p21 activation has been shown to induce apoptosis. In this study, Annexin V staining was used to show an increase in both early and late apoptosis.

One potential pathway for p21 mediated apoptosis is through a survivin dependent mechanism. Regulation of survivin is under the control of the RB/E2F family of proteins, which in turn are controlled by p21 32. The known abnormalities in the A498 cell line involve the hypoxia inducible factor pathway, and there are no known mutations in the Rb or E2F genes. Through quantitative PCR and Western blot analysis, we showed that following transfection with dsP21 there is a statistically significant decrease in both survivin message and protein. This association will need to be explored in future studies in order to determine causality.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Veterans Affairs Merit Review, Veterans Affairs Research Enhancement Award Program (REAP), and NIH grants: RO1CA111470, RO1CA101844, RO1CA 130860 and T32DK007790 (PI: Rajvir Dahiya).

References

- 1.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–11. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–8. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li LC, Okino ST, Zhao H, Pookot D, Place RF, Urakami S, Enokida H, Dahiya R. Small dsRNAs induce transcriptional activation in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17337–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607015103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bumcrot D, Manoharan M, Koteliansky V, Sah DW. RNAi therapeutics: a potential new class of pharmaceutical drugs. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:711–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dykxhoorn DM, Lieberman J. Running interference: prospects and obstacles to using small interfering RNAs as small molecule drugs. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:377–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aigner A. Gene silencing through RNA interference (RNAi) in vivo: strategies based on the direct application of siRNAs. J Biotechnol. 2006;124:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Place RF, Jia ZJ, Pookot D, Dahiya R, Li LC. Antitumor effect of dsRNA-induced p21(WAF1/CIP1) gene activation in human bladder cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:698–703. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez PL, Jares P, Rey MJ, Campo E, Cardesa A. Cell cycle regulators and their abnormalities in breast cancer. Mol Pathol. 1998;51:305–9. doi: 10.1136/mp.51.6.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niculescu AB, 3rd, Chen X, Smeets M, Hengst L, Prives C, Reed SI. Effects of p21(Cip1/Waf1) at both the G1/S and the G2/M cell cycle transitions: pRb is a critical determinant in blocking DNA replication and in preventing endoreduplication. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:629–43. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogryzko VV, Wong P, Howard BH. WAF1 retards S-phase progression primarily by inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4877–82. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gartel AL, Tyner AL. The role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:639–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss RH, Borowsky AD, Seligson D, Lin PY, Dillard-Telm L, Belldegrun AS, Figlin RA, Pantuck AD. p21 is a prognostic marker for renal cell carcinoma: implications for novel therapeutic approaches. J Urol. 2007;177:63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.073. discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janowski BA, Younger ST, Hardy DB, Ram R, Huffman KE, Corey DR. Activating gene expression in mammalian cells with promoter-targeted duplex RNAs. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:166–73. doi: 10.1038/nchembio860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, Noonan EJ, Dahiya R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang K, Zheng XY, Qin J, Wang YB, Bai Y, Mao QQ, Wan Q, Wu ZM, Xie LP. Up-regulation of p21WAF1/Cip1 by saRNA induces G1-phase arrest and apoptosis in T24 human bladder cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;265:206–14. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodel F, Hoffmann J, Grabenbauer GG, Papadopoulos T, Weiss C, Gunther K, Schick C, Sauer R, Rodel C. High survivin expression is associated with reduced apoptosis in rectal cancer and may predict disease-free survival after preoperative radiochemotherapy and surgical resection. Strahlenther Onkol. 2002;178:426–35. doi: 10.1007/s00066-002-1003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salz W, Eisenberg D, Plescia J, Garlick DS, Weiss RM, Wu XR, Sun TT, Altieri DC. A survivin gene signature predicts aggressive tumor behavior. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3531–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swana HS, Grossman D, Anthony JN, Weiss RM, Altieri DC. Tumor content of the antiapoptosis molecule survivin and recurrence of bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:452–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olie RA, Simoes-Wust AP, Baumann B, Leech SH, Fabbro D, Stahel RA, Zangemeister-Wittke U. A novel antisense oligonucleotide targeting survivin expression induces apoptosis and sensitizes lung cancer cells to chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2805–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sah NK, Khan Z, Khan GJ, Bisen PS. Structural, functional and therapeutic biology of survivin. Cancer Lett. 2006;244:164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akhtar S, Benter IF. Nonviral delivery of synthetic siRNAs in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3623–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI33494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang L, Igarashi M, Leung J, Sugrue MM, Lee SW, Aaronson SA. p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 induces permanent growth arrest with markers of replicative senescence in human tumor cells lacking functional p53. Oncogene. 1999;18:2789–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall MC, Li Y, Pong RC, Ely B, Sagalowsky AI, Hsieh JT. The growth inhibitory effect of p21 adenovirus on human bladder cancer cells. J Urol. 2000;163:1033–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karam JA, Fan J, Stanfield J, Richer E, Benaim EA, Frenkel E, Antich P, Sagalowsky AI, Mason RP, Hsieh JT. The use of histone deacetylase inhibitor FK228 and DNA hypomethylation agent 5-azacytidine in human bladder cancer therapy. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1795–802. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold NB, Arkus N, Gunn J, Korc M. The histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid induces growth inhibition and enhances gemcitabine-induced cell death in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:18–26. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richon VM, Sandhoff TW, Rifkind RA, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor selectively induces p21WAF1 expression and gene-associated histone acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10014–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zupanska A, Adach A, Dziembowska M, Kaminska B. Alternative pathway of transcriptional induction of p21WAF1/Cip1 by cyclosporine A in p53-deficient human glioblastoma cells. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1268–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorospe M, Wang X, Guyton KZ, Holbrook NJ. Protective role of p21(Waf1/Cip1) against prostaglandin A2-mediated apoptosis of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6654–60. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hitomi M, Shu J, Strom D, Hiebert SW, Harter ML, Stacey DW. Prostaglandin A2 blocks the activation of G1 phase cyclin-dependent kinase without altering mitogen-activated protein kinase stimulation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9376–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bissonnette N, Hunting DJ. p21-induced cycle arrest in G1 protects cells from apoptosis induced by UV-irradiation or RNA polymerase II blockage. Oncogene. 1998;16:3461–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fotedar R, Brickner H, Saadatmandi N, Rousselle T, Diederich L, Munshi A, Jung B, Reed JC, Fotedar A. Effect of p21waf1/cip1 transgene on radiation induced apoptosis in T cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:3652–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y, Saavedra HI, Holloway MP, Leone G, Altura RA. Aberrant regulation of survivin by the RB/E2F family of proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40511–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]