Abstract

Purpose

High-quality supportive care is an essential component of comprehensive cancer care. We implemented a patient-centered quality of cancer care survey to examine and identify predictors of quality of supportive care for bowel problems, pain, fatigue, depression, and other symptoms among 1,109 patients with colorectal cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients with new diagnosis of colorectal cancer at any Veterans Health Administration medical center nationwide in 2008 were ascertained through the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry and sent questionnaires assessing a variety of aspects of patient-centered cancer care. We received questionnaires from 63% of eligible patients (N = 1,109). Descriptive analyses characterizing patient experiences with supportive care and binary logistic regression models were used to examine predictors of receipt of help wanted for each of the five symptom categories.

Results

There were significant gaps in patient-centered quality of supportive care, beginning with symptom assessment. In multivariable modeling, the impact of clinical factors and patient race on odds of receiving wanted help varied by symptom. Coordination of care quality predicted receipt of wanted help for all symptoms, independent of patient demographic or clinical characteristics.

Conclusion

This study revealed substantial gaps in patient-centered quality of care, difficult to characterize through quality measurement relying on medical record review alone. It established the feasibility of collecting patient-reported quality measures. Improving quality measurement of supportive care and implementing patient-reported outcomes in quality-measurement systems are high priorities for improving the processes and outcomes of care for patients with cancer.

INTRODUCTION

In the past 10 years, there has been increasing evidence that supportive care for symptoms can greatly improve the quality of life and well-being of patients with cancer,1 reduce hospitalization rates,2 and improve overall survival.3,4 This evidence suggests that high-quality supportive care is an essential component of comprehensive cancer care. Consequently, quality-of-care measurement systems that lack valid measures of supportive care fail to provide the information needed to evaluate and improve a crucial component of cancer care. Unfortunately, most measurement systems fall short on assessment of interpersonal and technical quality of supportive care because they rely on data capture from medical records, a strategy that does not work well for supportive care processes for several reasons: (1) the variation and complexity of supportive care make it difficult to capture from medical records; (2) symptoms are subjective, and unlike indicators that rely on process-based measures like laboratory values or other test results, assessment relies on patient report; (3) cancer providers vary widely in their approach to symptom assessment and their way of recording symptoms once assessed5; (4) physicians tend to under-report the extent and severity of symptoms6,7; and (5) even when a single care setting or system implements standardized practices, they are not commonly implemented on a widespread basis. Consequently, there are few valid and reliable supportive care quality indicators that can be derived solely from medical record data.5,8 Furthermore, current recommendations and guidelines for supportive care specify several interpersonal processes of care, including rapid and comprehensive assessment and clear communication and information, as essential to quality of care.1,9–13 These interpersonal quality-of-care processes are also difficult to assess from medical record data alone, indicating that measuring patients' self-reported experiences of interpersonal quality of care is critical to comprehensive measurement of the quality of cancer care.14,15

This study attempts to address this gap in assessment of quality of supportive care through implementation of a patient-centered quality of colorectal cancer care (PCQ) questionnaire among patients treated in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) care system. We described patient reports on the quality of supportive care they received for bowel problems, pain, fatigue, depression, and other symptoms. We then examined the relationship between patient demographic and clinical characteristics, care coordination, and quality of patient-centered supportive care.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was part of a project testing a patient-reported outcomes quality measurement tool—the PCQ. The PCQ assessed a variety of aspects of patient-centered quality of care.16–18 It was approved by the institutional review boards of the Minneapolis and Durham Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Centers and the University of Minnesota.

Participants

Figure 1 depicts the flow of study participants. Living patients who received a new diagnosis of invasive colorectal cancer at any VHA medical center in 2008 were ascertained from the VA Central Cancer Registry. These 2,090 patients were mailed the self-administered PCQ, study information, and $10 incentive in late 2009. Among these, 262 reported that their diagnosis occurred before 2008, and 41 had died. Only 38 were women, reflecting their distribution in the population of veterans with colorectal cancer. Because the numbers were not sufficient to estimate sex differences, nor could the findings be generalized to care for women, they were eliminated from the sample. Of the remaining 1,749 eligible patients, 1,109 (63%) returned the PSQ.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram. CRC, colorectal cancer; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Data Sources

Demographic characteristics, listed in Table 1, were measured via self-report with commonly used questionnaire items, but when incomplete, they were supplemented with information from the VA Central Cancer Registry. Four-level cancer stage at diagnosis, according to the TNM system accepted by the American Joint Committee on Cancer, was ascertained from the cancer registry. Charlson comorbidity score19 was calculated using International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision) codes ascertained from the VA Central Cancer Registry. All other data came from the PCQ. Receipt of cancer treatment was assessed though patient self-report.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (N = 1,109)

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | Valid Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| < 65 | 470 | 42.4 |

| 65-79 | 466 | 42.0 |

| ≥ 80 | 173 | 15.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 147 | 13.5 |

| Hispanic | 59 | 5.4 |

| Non-Hispanic white and other | 884 | 81.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 579 | 52.2 |

| Unmarried (any reason) | 530 | 47.8 |

| Employment status | ||

| Retired | 674 | 62.1 |

| Disabled | 171 | 15.8 |

| Unemployed | 66 | 6.1 |

| Working full or part time | 169 | 15.6 |

| Homemaker | 2 | 0.2 |

| Student | 3 | 0.3 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 158 | 14.7 |

| High school graduate or GED | 399 | 37.1 |

| More than high school degree | 519 | 48.2 |

| Gross yearly income | ||

| < $20,000 | 615 | 62.1 |

| > $20,00 | 375 | 37.9 |

| Disease stage | ||

| I | 390 | 35.2 |

| II | 278 | 25.1 |

| III | 226 | 20.4 |

| IV | 185 | 16.7 |

| Unknown | 30 | 2.7 |

| Treatment | ||

| Received chemotherapy | 447 | 40.3 |

| Underwent surgery | 893 | 80.5 |

| Received radiation therapy | 184 | 16.6 |

Abbreviation: GED, general equivalency degree.

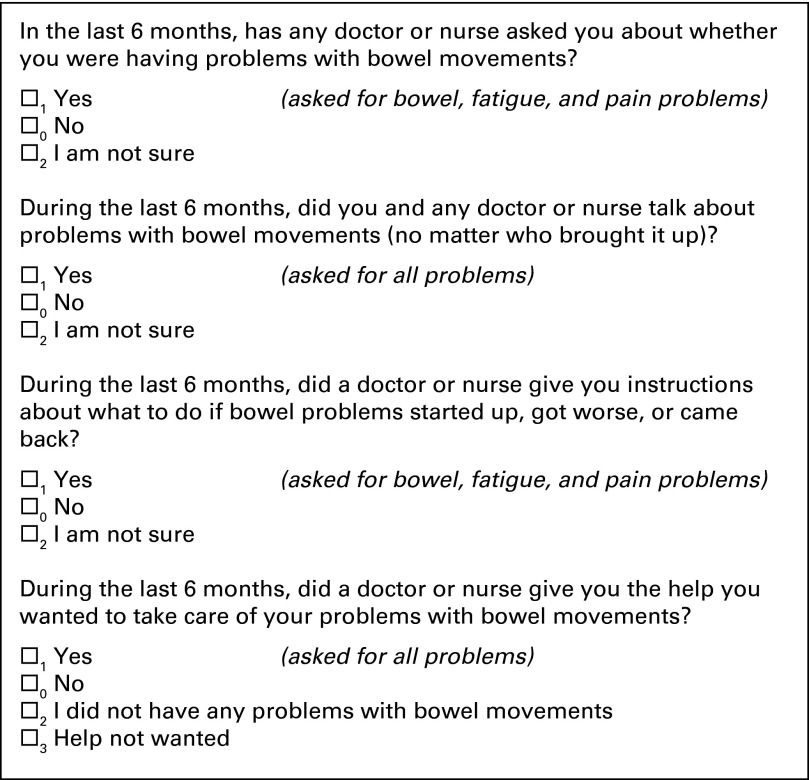

Measures of supportive care were designed to assess the interpersonal processes of care that would ideally occur for all patients regardless of symptom status. Measures were refined on the basis of results from two rounds of cognitive testing (n = 12) and one pilot test (n = 60). Cognitive testing involves conducting in-depth, semistructured interviews to investigate whether respondents understand the question correctly and if they can provide accurate answers. This insures that a question successfully captures the scientific intent of the question and, at the same time, makes sense to respondents.20,21 Figure 2 displays these items as they appeared on the questionnaire. For bowel problems, fatigue, and pain, patients were asked: whether a nurse or physician had asked them about the symptom; whether they talked about the symptom with any physician or nurse, no matter who brought it up; whether they were given information on what to do should the symptom occur, recur, or get worse; and whether they got the help they wanted for the symptom. To reduce respondent burden, patients were asked two of the items for depression and “other” symptoms: whether they talked about the symptom with any physician or nurse, and whether they received the help they wanted for the symptom. Questions appeared in order of the expected flow of patient care: being asked, discussing, and being given information about symptom. Patients who reported undergoing a colostomy or ileostomy skipped questions about bowel problems.

Fig 2.

Measures of patient-centered quality of supportive care.

Coordination of overall cancer care was measured using four items from a measure designed by the Picker Institute and used in prior studies of quality of patient-centered colorectal cancer care.22,23 These items measured how often a health care provider was familiar with a patient's medical history, was aware of changes in treatment that other providers recommended, and had all the information he or she needed to make decisions about treatment, as well as how often the patient knew who to ask when he or she had questions about health problems.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated item response frequencies for all items and scales. We then examined the proportionate drop-off in the flow of care from being asked about the symptom through receiving (or not) the help wanted for the symptom.

We next examined the proportion of patients who reported getting the help they wanted for each set of symptoms, excluding patients who reported they did not want or need help for the symptom. We then developed five binary logistic regression models to estimate the relationship between patient demographic factors, clinical characteristics, and quality of overall cancer care coordination and patient report that wanted help was received for bowel problems, pain, fatigue, depression, and other symptoms, respectively.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 lists patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Only 16% of patients were employed. Approximately 14% of patients were black, 5% were Hispanic, 3% were women, and more than half reported an income less than $20,000. This race distribution is similar to the VHA patient population (12% black, 6% Hispanic).24 A majority (80%) had undergone surgery, 40% had received chemotherapy, and 17% had received radiation treatment in the last year. Sixty percent had stage I or II, 20% had stage III, and 17% had stage IV disease.

Patient Reports on Quality of Supportive Care

Figure 3 illustrates both the percent of all patients reporting they experienced each process of supportive care as well as the drop-off in processes of care across the expected flow of patient care.

Fig 3.

Trajectory of supportive care; proportion of all respondents who responded yes to questions about care for symptoms.

Asked about symptoms.

Most patients reported that they were asked about bowel movements (73%) and pain (69%). Half (53%) reported they were asked about fatigue.

Discussion of symptoms.

Approximately half of patients had a discussion about pain (55%), fatigue (51%), and other symptoms (51%). More patients reported discussions of bowel problems (66%), and fewer reported discussions of depressive symptoms (33%). More patients reported they were asked about a symptom than reported having had a discussion of the symptom, no matter who brought it up. In cognitive testing, patients explained that they may have been asked about a symptom but did not go on to discuss the symptom. Among those who reported they were not ever asked about the symptom by a physician or nurse, 12%, 10%, and 8% reported they discussed bowel problems, fatigue, or pain symptoms anyway, respectively.

Instructions about symptoms.

When asked whether they received instructions about what to do if symptoms started up, got worse, or came back, 54%, 46%, and 28% reported receiving this information from a physician or nurse for bowel problems, pain, or fatigue, respectively.

Receiving wanted help for symptoms.

Table 2 lists the proportion of patients who reported getting the help they wanted for symptoms, excluding patients who reported not wanting or needing help for the respective symptoms. The percentage of patients who reported not needing or wanting help was 41% for pain, 33% for bowel problems and fatigue, 31% for depression, and 19% for other symptoms. Excluding patients who reported not wanting or needing help, 71%, 66%, 41%, 52%, and 38% reported receiving wanted help with bowel problems, pain, fatigue, other symptoms, or depression, respectively.

Table 2.

Overall Patient-Centered Quality of Care for Symptoms

| During the Last 6 Months, Did a Physician or Nurse Give You the Help You Wanted to Take Care of Your… | No |

Yes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Bowel problems? | 149 | 29 | 358 | 71 |

| Pain | 210 | 34 | 404 | 66 |

| Fatigue | 408 | 59 | 280 | 41 |

| Other problems (eg, nausea, sore tongue) | 369 | 48 | 396 | 52 |

| Depression (mood or emotions) | 403 | 62 | 242 | 38 |

NOTE. Patients who reported not wanting or needing help were excluded from analysis.

Predictors of receiving wanted help.

We examined the bivariate relationship between receiving wanted help for each of the five symptom categories (bowel problems, pain, fatigue, depression, and other symptoms) and patient age, race, ethnicity, education, employment, income, marital status, region, stage of disease, comorbidities, undergoing surgery, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy in the past year, and quality of coordination of cancer care. Education, income, marital status, region, comorbidities, and having undergone radiation treatment in the past year were nonsignificant in bivariable and multivariable analyses for all symptom types and were dropped from the analyses. Table 3 lists the results of multivariable binary logistic regression analyses. All the predictor variables in Table 3 are the same for each of the dependent variables, with the exception of symptom burden, which is specific to the dependent variable. For each independent variable, the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI are presented, and statistically significant coefficients (P ≤ .05) are indicated.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Model Analysis Predicting Patient Report of Receipt of Wanted Help for Bowel Problems, Pain, Fatigue, Depression, and Other Symptoms

| Characteristic | Bowel Problems (n = 505) |

Pain (n = 565) |

Fatigue (n = 623) |

Depression (n = 588) |

Other Physical Symptoms (n = 661) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| < 65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| 65-79 | 0.88 | 0.58 to 1.34 | 0.93 | 0.62 to 1.39 | 0.90 | 0.63 to 1.29 | 0.54* | 0.38 to 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.66 to 1.27 |

| ≥ 80 | 0.87 | 0.48 to 1.56 | 0.69 | 0.38 to 1.23 | 0.76 | 0.44 to 1.30 | 0.50* | 0.28 to 0.90 | 1.08 | 0.64 to 1.82 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 0.62† | 0.38 to 1.03 | 0.73 | 0.45 to 1.18 | 0.47* | 0.31 to 0.72 | 0.67† | 0.44 to 1.01 | 1.03 | 0.70 to 1.53 |

| Disease stage | ||||||||||

| IV | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| I | 0.43* | 0.23 to 0.82 | 0.31* | 0.17 to 0.57 | 0.29* | 0.17 to 0.50 | 0.54* | 0.32 to 0.90 | 0.42* | 0.25 to 0.69 |

| II | 0.72 | 0.37 to 1.42 | 0.56* | 0.30 to 1.05 | 0.48* | 0.29 to 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.39 to 1.11 | 0.42* | 0.26 to 0.68 |

| III | 0.58 | 0.30 to 1.14 | 0.44* | 0.23 to 0.84 | 0.41* | 0.25 to 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.38 to 1.06 | 0.44* | 0.27 to 0.73 |

| Treatment | ||||||||||

| Surgery in last year | 0.71 | 0.43 to 1.18 | 0.55* | 0.33 to 0.91 | 0.57* | 0.37 to 0.86 | 1.13 | 0.73 to 1.75 | 0.61* | 0.40 to 0.92 |

| Chemotherapy in last year | 2.93* | 1.80 to 4.77 | 2.32* | 1.47 to 3.64 | 1.29 | 0.86 to 1.92 | 1.31 | 0.87 to 1.97 | 2.11* | 1.44 to 3.10 |

| Coordination of care | 1.71* | 1.38 to 2.12 | 1.79* | 1.46 to 2.20 | 1.55* | 1.29 to 1.85 | 1.11 | 0.94 to 1.31 | 1.29* | 1.10 to 1.52 |

NOTE. Patients who reported not wanting or needing help were excluded from analysis.

Statistically significant coefficient (P ≤ .05).

Borderline statistical significance (P < .06).

Demographic factors.

In the multivariable models listed in Table 3, non-Hispanic white patients were less likely than minority race/ethnicity patients to report receiving help for fatigue (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.72), bowel problems (OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.37 to 1.03), and depression (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.44 to 1.01), although this effect was only statistically significant for fatigue (P ≤ .01) and was of borderline statistical significance for bowel problems and depression (P < .06). Older patients were less likely to report receiving the help they wanted for depression (age 65 to 79 years: OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.79; age > 80 years: OR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.28 to 0.90) than patients younger than age 65 years. There was insufficient statistical power to examine differences between nonwhite groups.

Clinical factors.

Patients with stage I to III disease were less likely to report receiving the help they wanted for pain, fatigue, depression, and other symptoms than were patients with stage IV disease. Patients who had surgery in the past year were less likely to report receiving the help they needed for pain (OR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.91), fatigue (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.37 to 0.86), and other symptoms (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.92). In contrast, patients who had undergone chemotherapy in the past year were significantly more likely to report receiving the help they wanted for bowel problems (OR, 2.93; 95% CI, 1.80 to 4.77), pain (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.47 to 3.64), and other problems (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.44 to 3.10).

Coordination of overall cancer care.

Higher scores on the coordination of care scale were associated with significantly higher odds of receiving needed help with bowel problems (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.38 to 2.12), pain (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.46 to 2.20), fatigue (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.29 to 1.85), and other symptoms (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.52) and higher but not statistically significant odds of receiving help for depressive symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Our findings revealed substantial gaps in patient-centered processes of care for symptoms among patients with colorectal cancer. Symptom assessment served as a gateway to receipt of other supportive care processes. Few patients reported having a discussion of symptoms unless they also reported that they were specifically asked about symptoms. This is consistent with other findings indicating that patients who are not directly asked about symptoms are often hesitant to mention them.25 When patients reported they were asked about symptoms, most reported receiving the help they wanted for the symptoms, suggesting that strategies that create consistent symptom assessment may create important gains in quality of supportive care.26,27

Improving symptom assessment is necessary but not sufficient. A substantial minority of patients who reported being asked about and/or discussing their symptoms with a physician or nurse also reported not getting the help they wanted for symptoms. The reasons for this are unclear. Effective quality improvement efforts will be dependent on a more detailed understanding of the causes of these gaps in care, making this an important priority for future research. Furthermore, although there were gaps in care for all symptoms, the gaps in care for depression were especially notable. Only one third of patients reported discussing mood despite psychosocial guidelines recommending screening for distress.9,28–33

Non-Hispanic white patients were less likely than others to report getting the help they wanted for fatigue, bowel problems, and depression symptoms in this sample of VA patients, although the bowel and depression symptom effects only achieved borderline statistical significance (P < .06). This finding is inconsistent with those of a large number of studies finding a minority disadvantage both inside34 and outside of the VA.35–43 The cause of this difference is unknown. Speculatively, it could be the result of different expectations for symptom control among white and nonwhite patients. It is also possible that VA efforts to reduce racial disparities and minority disadvantage in care44 have resulted in cancer providers paying more attention to symptoms in their nonwhite compared with white patients.

Advanced stage of disease was the most consistent clinical predictor of patients' receiving the help they wanted for all symptom categories. This finding suggests that suffering among patients with nonmetastatic cancer may be overlooked.

Patients who received chemotherapy in the past year were more likely to report receiving wanted help for all symptoms other than depression, independent of all other variables. Conversely, patients who had undergone surgery in the past year had lower odds of reporting receiving the help they wanted for pain and other physical symptoms. Although it is possible that oncology practices in the VA provided better symptom management than surgical practices, these findings deserve further examination.

Coordination of cancer care consistently predicted receipt of wanted help. This finding reinforces the importance of coordination of care for the timeliness45 and quality of cancer care46,47 and adds weight to the growing emphasis on policies and practices that improve coordination of care for patients with cancer.48–50

This study had several strengths. A large, national population of patients receiving care in an integrated health care system was included. Response rates were unassociated with patient sociodemographic characteristics. Measures were created on the basis of evidence regarding questions that were most salient to patient-centered care. To ensure applicability to this patient population, the measures also underwent careful and thorough cognitive and pilot testing.

This study also had potential limitations. The study was cross-sectional, so the causal direction of predictive analyses cannot be definitively established. Our response rate was consistent with those of other outpatient surveys of patients with cancer,47,51–54 but response may have been associated with our outcomes of interest; patients who were either very satisfied or very unsatisfied with care may have been more likely to respond. Patient self-report, although the gold standard for patient-reported outcomes and assessment of patient-centered care, is subject to recall bias. This bias may be affected by current symptom level and could cause either over- or underestimates of gaps in care.55–58 VA health care delivery may not be generalizable to other health care systems. Previous estimates of the quality of cancer care in the VA demonstrate that it is the same or better than care received by fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries.59 Therefore, our assessment of the quality of supportive cancer care likely represents a best-case scenario for US health care. However, the small number of women and their resulting exclusion from these analyses prohibit generalizability to female cancer survivors.

This study revealed substantial gaps in patient-centered quality of care that would be difficult to characterize through medical record review. It also established the feasibility of collecting patient-reported quality assessment measures. Quality measures create the basis for prioritization, accountability, quality improvement, and transparency in the health care system. The lack of routine implementation of such measures leaves health care systems without the information needed to identify patient needs, target resources for improvement, and evaluate the impact of quality improvement activities. These findings provide support for routinely incorporating patient surveys into comprehensive quality-of–cancer care measurement systems and suggest where significant quality improvement efforts are needed.48,60

Acknowledgment

We thank Deborah Finstad, who provided programming and research assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by the Interagency Quality of Cancer Care Committee, Applied Research Branch, National Cancer Institute (NCI), through an interagency agreement with the Veterans Health Administration and by NCI Grant No. 5R25CA116339 (L.L.Z.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) and/or an author's immediate family member(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: S. Yousuf Zafar, Genentech (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Patents: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Michelle van Ryn, Sean M. Phelan, Neeraj K. Arora, David A. Haggstrom, George L. Jackson, S. Yousuf Zafar, Joan M. Griffin, Leah L. Zullig, Dawn Provenzale, Rahul M. Jindal, Steven B. Clauser

Collection and assembly of data: Michelle van Ryn, Sean M. Phelan

Data analysis and interpretation: Michelle van Ryn, Sean M. Phelan, George L. Jackson, S. Yousuf Zafar, Mark W. Yeazel

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Olver IN, editor. The MASCC Textbook of Cancer Supportive Care and Survivorship. Hillerød, Denmark: Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner-Johnston ND, Carson KA, Grossman SA. High outpatient pain intensity scores predict impending hospital admissions in patients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temel JS, Pirl WF, Lynch TJ. Comprehensive symptom management in patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:241–249. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenz KA, Dy SM, Naeim A, et al. Quality measures for supportive cancer care: The Cancer Quality-ASSIST Project. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:943–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laugsand EA, Sprangers MA, Bjordal K, et al. Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: A multicenter European study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sneeuw KC, Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:1130–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dy SM, Lorenz KA, O'Neill SM, et al. Cancer Quality-ASSIST supportive oncology quality indicator set: Feasibility, reliability, and validity testing. Cancer. 2010;116:3267–3275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Distress management. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#distress.

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Adult cancer pain. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#pain.

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Cancer-related fatigue. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#fatigue.

- 12.Ripamonti CI, Santini D, Maranzano E, et al. Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 7):vii139–vii154. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell D, Keller-Olaman S, Oliver TK, et al. A pan-Canadian practice guideline and algorithm: Screening, assessment, and supportive care of adults with cancer-related fatigue. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:e233–e246. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1999. Measuring the Quality of Health Care: A Statement by the National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hewitt M, Simone JV, editors. Enhancing Data Systems to Improve the Quality of Cancer Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Provenzale D, et al. Transportation: A vehicle or roadblock to cancer care for VA patients with colorectal cancer? Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2012;11:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zullig LL, Jackson GL, Provenzale D, et al. Utilization of hospital-based chaplain services among newly diagnosed male Veterans Affairs colorectal cancer patients. J Relig Health. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9653-2. [epub ahead of print on October 11, 2012] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelan SM, Griffin JM, Jackson GL, et al. Stigma, perceived blame, self-blame, and depressive symptoms in men with colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:65–73. doi: 10.1002/pon.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis GB. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design—A Practical “How-To” Guide With Advice. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beaty PC, Willis GB. Research Synthesis: The practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opin Q. 2007;71:287–311. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, et al. Patients' perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6576–6586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hays RD, Eastwood JA, Kotlerman J, et al. Health-related quality of life and patient reports about care outcomes in a multidisciplinary hospital intervention. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:173–178. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Veterans Affairs. 2011 Survey of Veteran Enrollees' Health and Reliance Upon VA. http://www.va.gov/healthpolicyplanning/soe2011/soe2011_report.pdf.

- 25.Back A. Patient-physician communication in oncology: What does the evidence show? Oncology (Williston Park) 2006;20:67–74. discussion 77–78, 83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruera E. Routine symptom assessment: Good for practice and good for business. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:537–538. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abernethy AP, Wheeler JL, Zafar SY. Detailing of gastrointestinal symptoms in cancer patients with advanced disease: New methodologies, new insights, and a proposed approach. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3:41–49. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32832531ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB. Progress in the implementation of NCCN guidelines for distress management by member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:223–226. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burg MA, Adorno G, Hidalgo J. An analysis of Social Work Oncology Network Listserv postings on the Commission of Cancer's distress screening guidelines. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:636–651. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.721484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Symptom management in cancer—Pain, depression, and fatigue, July 15-17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:9–16. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/djg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells-Di Gregorio S, Porensky EK, Minotti M, et al. The James Supportive Care Screening: Integrating science and practice to meet the NCCN guidelines for distress management at a comprehensive cancer center. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2001–2008. doi: 10.1002/pon.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holland JC. Preliminary guidelines for the treatment of distress. Oncology (Williston Park) 1997;11:109–114. discussion 115-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark PG, Bolte S, Buzaglo J, et al. From distress guidelines to developing models of psychosocial care: Current best practices. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:694–714. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.721488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA health care system: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:654–671. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moy E, Dayton E, Clancy CM. Compiling the evidence: The National Healthcare Disparities Reports. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:376–387. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bickell NA, Paskett ED. Reducing inequalities in cancer outcomes. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013;2013:250–254. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, et al. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisch MJ, Lee JW, Weiss M, et al. Prospective, observational study of pain and analgesic prescribing in medical oncology outpatients with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1980–1988. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Traeger L, Cannon S, Pirl WF, et al. Depression and undertreatment of depression: Potential risks and outcomes in black patients with lung cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2013;31:123–135. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.761320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spencer BA, Insel BJ, Hershman DL, et al. Racial disparities in the use of palliative therapy for ureteral obstruction among elderly patients with advanced prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1303–1311. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer NR, Geiger AM, Felder TM, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in health care receipt among male cancer survivors. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1306–1313. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephenson N, Dalton JA, Carlson J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer pain management. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2009;20:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green CR, Hart-Johnson T, Loeffler DR. Cancer-related chronic pain: Examining quality of life in diverse cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:1994–2003. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fine MJ, Demakis JG. The Veterans Health Administration's promotion of health equity for racial and ethnic minorities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1622–1624. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X, Scarfe A, King K, et al. Timeliness of cancer care from diagnosis to treatment: A comparison between patients with breast, colon, rectal or lung cancer. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:197–204. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aiello Bowles EJ, Tuzzio L, Wiese CJ, et al. Understanding high-quality cancer care: A summary of expert perspectives. Cancer. 2008;112:934–942. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, et al. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor's perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1280–1289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schrag D. Communication and coordination: The keys to quality. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6452–6455. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De P, Ellison LF, Barr RD, et al. Canadian adolescents and young adults with cancer: Opportunity to improve coordination and level of care. CMAJ. 2011;183:E187–E194. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nelson R. PACT Act may improve cancer care for Medicare patients. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/807056.

- 51.Paika V, Almyroudi A, Tomenson B, et al. Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients' quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity. Psychooncology. 2010;19:273–282. doi: 10.1002/pon.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harrison SE, Watson EK, Ward AM, et al. Primary health and supportive care needs of long-term cancer survivors: A questionnaire survey. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2091–2098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corner J, Wagland R, Glaser A, et al. Qualitative analysis of patients' feedback from a PROMs survey of cancer patients in England. BMJ Open. 2013:3. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Catalano PJ, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, et al. Representativeness of participants in the cancer care outcomes research and surveillance consortium relative to the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Med Care. 2013;51:e9–e15. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coughlin S. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans C, Crawford B. Patient self-reports in pharmacoeconomic studies: Their use and impact on study validity. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15:241–256. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199915030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hunger M, Schwarzkopf L, Heier M, et al. Official statistics and claims data records indicate non-response and recall bias within survey-based estimates of health care utilization in the older population. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burgess DJ, Powell AA, Griffin JM, et al. Race and the validity of self-reported cancer screening behaviors: Development of a conceptual model. Prev Med. 2009;48:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Quality of care for older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:727–736. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-11-201106070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lorenz K, Lynn J, Dy S, et al. Cancer care quality measures: Symptoms and end-of-life care. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2006;137:1–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]