Abstract

Background and Aims

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) requires rapid diagnosis and the initiation of antibiotics. Diagnosis of SBP is usually based on cytobacteriological examination of ascitic fluid. These tests require good laboratory facilities and reporting time of few hours to 1–2 day. However, the 24 h laboratory facilities not widely available in country like India. We evaluated the diagnostic utility of reagent strip (Multistix 10 SG®) for rapid diagnosis of SBP.

Material and methods

The study was prospectively carried out on patients of cirrhosis with ascites. Bedside leukocyte esterase reagent strip testing was performed on ascitic fluid. Cell count as determined by colorimetric scale of reagent strip was compared with counting chamber method. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy were calculated.

Result

Out of 100 patients with cirrhotic ascites, [72 males: 28 female; mean age 44.34 (SD 13.03) years] 18 patients were diagnosed to have SBP by counting chamber method as compared to 14 patients detected to have SBP by reagent strip test ≥++ positive. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of reagent strip ≥++ positive were 77.77%, 95.12%, 77.77%, 95.12% and 92% respectively compared to counting chamber method.

Conclusion

Reagent strip to diagnose SBP is very specific but less sensitive as compared to counting chamber method. This can be performed rapidly, easily and efficiently even in remote area of developing countries. This bedside test could be a useful tool for the diagnosis of SBP in country like India.

Keywords: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, leukocyte esterase dipstick test, Multistix 10 SG® reagent strips

Abbreviations: SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; AF, ascitic fluid; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte; LERS, leukocyte esterase reagent strips; PPV, positive predictive values; NPV, negative predictive values; SAAG, serum-ascites albumin gradient

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a potentially life-threatening complication of liver cirrhosis with ascites.1 The prevalence of SBP in hospitalized patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites is up to 30%. The in-hospital mortality rate is also very high (30%–50%).2

SBP requires timely diagnosis that is usually based on total and differential leukocyte count of ascitic fluid (AF). A polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) cell count in AF >250/mm3, irrespective of the AF culture, is the diagnostic criterion of SBP.1 The urgent leukocyte count of the AF is warranted for the initiation of appropriate antibiotics.2,3 However, 24 h laboratory facilities are not available in many hospitals. This is particularly true in developing country like India. Therefore, alternative methods for rapid diagnosis of SBP are an obvious requirement.4,5 Use of reagent strip testing for leukocyte esterase has been described in order to reduce the time from paracentesis to a provisional diagnosis of SBP from a few hours to a few minutes.5,6 The reagent strips detecting leukocyte esterase activity in biological fluids have been validated for the diagnosis of urinary tract infections, meningitis, and pleural infections.7–9

Aim of the study was to determine the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPV), negative predictive values (NPV), and accuracy of leukocyte esterase reagent strips (LERS) for the diagnosis of SBP in cirrhotic patients with ascites.

Materials and methods

This study was prospectively conducted at the Department of Internal Medicine, Rabindra Nath Tagore (RNT) Medical College, Udaipur, India from April 2005 to June 2007. The local ethics committee of the RNT medical college, Udaipur approved the study and informed consent was obtained from each patient.

A total of one hundred liver cirrhotic patients with ascites, who were hospitalized, were included in this study. The patients of ascites were admitted with the following indications: a) large or tense ascites; b) mild to moderate ascites associated with other complications of CLD such as coagulopathy, encephalopathy, hypotension, shock, past or present history of gastrointestinal bleeding, dyselectrolytemia and renal impairment; c) on treatment worsening of ascites; d) for investigation of cause of CLD; and f) for the purpose of monitoring of serum and urine electrolyte and education regarding dietary salt restriction. Patients with low SAAG and hemorrhagic ascites and those who were receiving any antibiotics were excluded. All patients were tested for complete blood count, liver function tests, alpha-fetoprotein, renal function tests, prothrombin time, serum electrolytes, urine routine microscopic examination and culture, chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasonography and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Appropriate tests for viral hepatitis, autoimmune liver disease, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis were performed. Diagnosis of cirrhosis was established by clinical, laboratory, endoscopic and/or ultrasonographic findings.

Paracentesis was performed under strict aseptic condition at admission and during the hospital stay for treatment of ascites or with clinical signs of SBP. Immediately after the paracentesis, AF was tested using LERS (Multistix 10 SG®, Bayer Diagnostics, Illinois). The LERS was immersed in 5 mL of AF placed on a dry and clean container as described by the manufacturer for identification of leukocyte esterase. After 2 min, the LERS was read comparing the color of the leukocyte reagent strip area with the colorimetric scale depicted on the bottle. The strips had a colorimetric 5-grade scale. A correlation between leukocyte and a 5-grade scale was suggested by the manufacturer, as follows: grade 0, 0 leukocyte/mm3; grade trace, 15 leukocyte/mm3; grade + (small), 70 leukocyte/mm3; grade ++ (moderate), 125 leukocyte/mm3; and grade +++ (large), 500 leukocyte/mm3. Two different cut-offs, grade ++ or grade +++ were tested. Laboratory analysis of the AF was performed without delay in all patients. For testing a standard sterile technique was used and included total and differential cell counts, Gram stain, total protein and albumin levels. Leukocytes cell count in AF was done by counting chamber methods using microscopy, and percentage of PMN was determined using methylene blue stain on a concentrated smear of AF collected in EDTA. Cultures of AF were done at bedside using blood culture bottles. Ten milliliter of AF was inoculated into each bottle. The diagnosis of SBP was based on a PMN cell count >250/mm3 in AF, irrespective of AF culture result, and an absence of intra-abdominal sources of infection, inflammation or tuberculosis.

After paracentesis, suspected SBP was treated with intravenous cefotaxime initially empirically and later according to the culture sensitivity patterns. Appropriate treatments for etiology and complications of cirrhosis were done. Patients were discharged on primary or secondary prophylaxis for SBP according to clinical profile of patient.

Data are presented as means ± SD for quantitative variables and as frequencies for qualitative variables. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy were calculated.

Results

One hundred patients of cirrhotic ascites were enrolled (72 were males and 28 were females), mean (SD) age was 44.34 (±13.03) years. Of the 100 patients, there were 73 (73%) with Child class C and 27 (27%) with Child class B. The etiology of cirrhosis was alcohol in 42 (42%), chronic B hepatitis in 22 (22%), chronic C hepatitis in 12 (12%), and other causes in 24 (24%).

Eighteen patients (18%) were diagnosed to have SBP by counting chamber method as compared to 12 (12%) detected to have SBP by LERS test +++ positive. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of LERS+++ positive were 66.66%, 100%, 100%, 93.18% and 94% respectively compared to cell count by manual counting chamber method. When we considered LERS test ≥++ as cut-off, 14 patients (14%) detected to have SBP. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of LERS ≥++ positive were 77.77%, 95.12%, 77.77%, 95.12% and 92% respectively compared to cell count by manual counting chamber method (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Final diagnosis of ascitic fluid samples and Multistix 10 SG® RS test result.

| Diagnosis | Reagent strip result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (0 leukocytes/mm3) | Trace (15 leukocytes/mm3) | + (70 leukocytes/mm3) | ≥++ (125 leukocytes/mm3) | +++ (500 leukocytes/mm3) | |

| Cirrhotic ascites (non-SBP) | 60 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| SBP culture (+) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| SBP culture (−) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 10 |

| SBP (total) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 12 |

SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; RS: reagent strip.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and accuracy of Multistix 10 SG® RS, using two different cut-off.

| Variable | RS ≥++ (%) | RS = +++ (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 77.77 | 66.66 |

| Specificity | 95.12 | 100.0 |

| PPV | 77.77 | 100 |

| NPV | 95.12 | 93.18 |

| Accuracy | 92 | 94 |

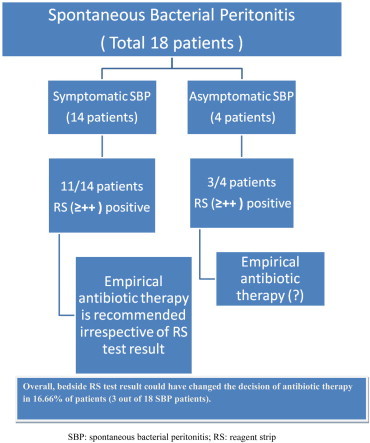

Out of 18 patients of SBP, 14 patients were symptomatic (fever, abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness and others). LERS test result ≥++ was positive in 11 of 14 symptomatic SBP patients. Empiric antibiotic was started in all symptomatic patients immediately after paracentesis. The remaining 4 patients had no clinical feature suggestive of SBP. LERS test result ≥++ was positive in 3 out of 4 these asymptomatic SBP patients (Figure 1). The sensitivity of LERS test (≥++ as cut-off) in symptomatic and asymptomatic SBP was 78.57% and 75% respectively.

Figure 1.

Reagent strip test result and early antibiotic treatment in SBP.

The mean (SD) cell count in patients with grade +++ change was 1805 (1167) leukocyte/mm3 and that in those with grade ++ change was 743 (517) leukocyte/mm3. Culture of AF was positive in 4 (22.22%) cases and negative in 14 (77.77%) cases. The bacterium isolated from cultures of AF was Escherichia coli.

Discussion

Rapid diagnosis and treatment are very important in the management of SBP, a potentially dangerous complication of cirrhosis. The yield of bacterial culture is usually low (up to 40%) in these groups of patients, and that test results may be delayed for several days. Therefore, a polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) cell count in AF >250/mm3, irrespective of the AF culture, is the diagnostic criterion of SBP.1 The manual cell count of AF is standard method. However, the AF manual cell count has a few problems. It is not always available in all hospitals, especially on an emergency basis. Reporting usually requires few hours and sometimes 1–2 days. Sometimes, there is formation of the leukocyte clump in AF precludes the laboratory analysis of AF even in a tertiary care hospital. In our study, repeat AF samples were required on six occasions. Unfortunately, we do not have data regarding the categorical reason of repeat AF sample demand by the laboratory.

Recently, reagent strips have emerged as an attractive means for rapid diagnosis of SBP. These tests have the ability to detect esterase activity of PMN cells.10 These cells release leukocyte esterase into the extracellular milieu reacts with an ester releasing 3-hydroxy-5-phenyl-pyrrole which causes a color change in the azo dye in the reagent strip.

Numerous independent studies have evaluated the diagnostic value of LERS (Multistix®, Combur®, Nephur®, UriScan® and Aution® strips) in settings involving SBP. The published studies have shown widely variable results in term of sensitivity specificity, PPV and NPV. Compared with the manual PMN count (‘gold standard’), LERS were found to have sensitivity ranging from 45 to 100%, specificity ranging from 81 to 100%, PPV value ranging from 42 to 100% and NPV ranging from 87 to 100%.4–6,11–24 Similarly, the published studies in which Multistix reagent strips were used have also shown widely variable test results (Table 3).4,12–14,17–20,24 In an only study from India, authors have shown the Multistix strip's sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of 97%, 89%, 87% and 83% respectively using a cut-off of grade 2. However, when using a cut-off of grade 3, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were 92%, 100%, 100% and 98% respectively.24 Our study showed less sensitivity but high specificity and NPV (Table 2). The result of our study was nearly similar to studies published by Butani et al and Ribeiro et al.14,20 Our study expands previous findings of the potential utility of the LERS test as a simple, rapid and inexpensive means for testing in settings involving SBP. If we compare two cut-offs (≥++ and +++) used by us, both had performed fairly well for the diagnosis of SBP. Notably, the selection of a cut-off point +++ yielded 100% specificity and 100% PPV for the diagnosis of SBP. By contrast, results of an LERS test ≥++ yielded 77.77% sensitivity and 95.12% NPV, which excluded SBP in these individuals. It may be better to use the cut-off of ≥++ with a higher sensitivity and higher NPV, even at the cost of some false positives.

Table 3.

The Multistix reagent strip: range of results in various studies.4,12–14,17–20,24

| Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade ≥1 (15 leukocytes/mm3) | 64.7–100 | 83–100 | 42–100 | 96–100 |

| Grade ≥2 (70 leukocytes/mm3) | 45.7–100 | 98–99 | 75–99 | 93.3–100 |

| Grade ≥3 (125 leukocytes/mm3) | 45.3–89 | 99.2–100 | 77.2–100 | 94–99 |

PPV: positive predictive values; NPV: negative predictive values.

Two recently published systematic reviews have pointed the heterogeneity in the number of patients included in each study, the AF samples tested and SBP episodes observed, as well as in all measures of LERS performance.25,26 The other limitations of the RS test include the possibility of inter-observer variation in matching of color. There is dichotomy of opinion regarding the use of LERS test in SBP. Because of wide variation in sensitivity and PPV between reported studies, some authors have raised doubt over the use of LERS as a valid surrogate marker of SBP.25 However, because of the consistently excellent NPV (>95% in the majority of the studies) of LERS, others have advocated its place in the ascitic tap diagnostic algorithm specially as a preliminary screening tool for SBP diagnosis.26,27

The reagent strip has several advantages, such as: it is easy to use, there is no need of expertise for matching of color, and very rapid (takes 90–120 s). With use of bedside LERS test early antibiotic therapy can be started in a fair percentage of asymptomatic SBP patients. On the basis of LERS test ≥++ result; we could have started early treatment in 3 out of 4 asymptomatic SBP patients. Despite the lower sensitivity of LERS test in our study, decision of antibiotic therapy could have changed in 16.66% of patients (3 out of 18 SBP patients) (Figure 1).

Furthermore, it is much cheaper than the manual cell count. The cost of one reagent strip is Rs 15–20 Indian rupees (INR) and the cost of manual cell count ranges between Rs 200–350 Indian rupees (INR). In case of urgent reporting (especially at night time or on vacations or on week-ends), cost may be 30–50% higher in comparison to the routine cost.

Our study has a few limitations. Firstly, there was relatively small sample size. Secondly, reading of colorimetric scale was performed by single examiner. Therefore, one cannot deny the possibility of inter-observer variation. Finally, there was absence of a cut-off corresponding to cell count of 250 PMN/mm3.

To summarize, as the laboratory facilities still not widely available in country like India use of this cheap, easy to use and rapid bedside test could be rewarding in fair proportion of SBP patients. In patients of cirrhotic ascites with positive LERS test results, first dose of antibiotic therapy should be started without delay. As the standard ascites analysis remains the gold standard for SBP diagnosis, further management could be planned after result of cytobacteriological examination.

In conclusion, LERS test is a useful tool for the very rapid diagnosis of SBP. Specifically, this test can be performed easily and efficiently even in remote area of developing countries where the facilities to carry out lymphocyte count of AF are scarce. Furthermore, bedside LERS test (≥++ as cut-off) can be used to start early antibiotic therapy in asymptomatic SBP. Hence, it can be rewarding even in a tertiary care center.

Declarations

Ashish Kumar Jha has worked in Department of Medicine, Rabindra Nath Tagore Medical College, Udaipur, India. Mahesh Kumar Goenka has substantially contributed in analysis of data and preparation of manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Rimola A., Garcia-Tsao G., Navasa M. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000;32:142–153. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gines P., Cardenas A., Arroyo V., Rodes J. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1646–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheer T.A., Runyon B.A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis. 2005;23:39–46. doi: 10.1159/000084724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campillo B., Richardet J.P., Dupeyron C. Diagnostic value of two reagent strips (Multistix 8 SG and Combur 2 LN) in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and symptomatic bacterascites. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:446–452. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaya D.R., Lyon T David B., Clarke J. Bedside leucocyte esterase reagent strips with spectrophotometric analysis to rapidly exclude spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a pilot study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:289–295. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328013e991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellote J., Lopez C., Gornals J. Rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis by use of reagent strips. Hepatology. 2003;37:893–896. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel H.D., Livsey S.A., Swann R.A., Bukhari S.S. Can urine dipstick testing for urinary tract infection at point of care reduce laboratory workload? J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:951–954. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.025429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moosa A.A., Quortum H.A., Ibrahim M.D. Rapid diagnosis of bacterial meningitis with reagent strips. Lancet. 1995;345:1290–1291. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90931-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azoulay E., Fartoukh M., Galliot R. Rapid diagnosis of infectious pleural effusions by use of reagent strips. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:914–919. doi: 10.1086/318140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rerknimitr R., Rungsangmanoon W., Kongkam P., Kullavanijaya P. Efficacy of leukocyte esterase dipstick test as a rapid test in diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7183–7187. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i44.7183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanbiervliet G., Rakotoarisoa C., Filippi J. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid urine-screening test (Multistix®8SG) in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1257–1260. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delaunay-Tardy K., Cottier M., Patouillard B., Audigier J.C. Early diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis by Multistix® strips with spectrophotometric reading device: a poor sensitivity. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2003;27:A166. (Abstract, French) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thévenot T., Cadranel J.F., Nguyen-Khac E. Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients by use of two reagent strips. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:579–583. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200406000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butani R.C., Shaffer R.T., Szyjkowski R.D., Weeks B.E., Speights L.G., Kadakia S.C. Rapid diagnosis of infected AF using leukocyte esterase dipstick testing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:532–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sapey T., Mena E., Fort E. Rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with leukocyte esterase reagent strips in a European and in an American center. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapey T., Kabissa D., Fort E., Laurin C., Mendler M.H. Instant diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis using leukocyte esterase reagent strips: Nephur®-Test vs. Multistix®SG. Liver Int. 2005;25:343–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisniewski B., Rautou P.E., Al Sirafi Y. Diagnosis of spontaneous ascites infection in patients with cirrhosis: reagent strips. Presse Med. 2005;27:34. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(05)84098-9. (French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D.K., Suh D.J., Kim G.D. Usefulness of reagent strips for the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Korean J Hepatol. 2005;11:243–249. (Korean) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nousbaum J.B., Cadranel J.F., Nahon P. Diagnostic accuracy of the Multistix®8 SG reagent strip in diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1275–1281. doi: 10.1002/hep.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro T.C., Kondo M., Amaral A.C., Parise E.R., Bragagnolo Junior M.A., Souza A.F. Evaluation of reagent strips for AF leukocyte determination: is it a possible alternative for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis rapid diagnosis? Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:70–74. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702007000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarwar S., Alam A., Izhar M. Bedside diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis using reagent strips. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:418–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim D.Y., Kim J.H., Chon C.Y. Usefulness of urine strip test in the rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2005;25:1197–2101. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braga L.L., Souza M.H., Barbosa A.M., Furtado F.M., Campelo P.A., Araújo Filho A.H. Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients in northeastern Brazil by use of rapid urine-screening test. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006;124:141–144. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802006000300006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balagopal S.K., Sainu A., Thomas V. Evaluation of leucocyte esterase reagent strip test for the rapid bedside diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:74–77. doi: 10.1007/s12664-010-0017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen-Khac E., Cadranel J.F., Thevenot T., Nousbaum J.B. Review article: the utility of reagent strips in the diagnosis of infected ascites in cirrhotic patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koulaouzidis A., Leontiadis G.I., Abdullah M. Leucocyte esterase reagent strips for the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:1055–1060. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328300a363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koulaouzidis A. Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: an update on leucocyte esterase reagent strips. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1091–1094. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i9.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]