Abstract

Post-gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) women are recommended weight loss to manage increased cardio-metabolic risks. We investigated the effects of lowering diet glycaemic index (GI) on fasting blood glucose (FBG), serum lipids, body weight and composition of post-GDM women with varying fasting insulin levels (INS). Seventy-seven Asian, non-diabetic women with previous GDM (aged 20–40 years, mean BMI: 26.4±4.6 kg m−2) were recruited. At baseline, 20 subjects with INS <2 μIU ml−1 and 18 with INS ⩾2 μIU ml−1 received conventional dietary recommendations (CHDR) only. CHDR emphasised energy and fat intake restriction and encouraged increase in dietary fibre intakes. Twenty-four subjects with INS <2 μIU ml−1 and 15 with INS ⩾2 μIU ml−1, in addition to CHDR, received low-GI education (LGI). Changes in FBG, serum lipids, body weight and body composition were evaluated. Subjects with INS <2 μIU ml−1 had similar outcomes with both diets. After 1 year, subjects with INS ⩾2 μIU ml−1 who received LGI education had reductions in FBG and triglycerides. Subjects who received CHDR observed increase in both FBG and triglycerides (P<0.05). Among all subjects, diet GI was lower and dietary fibre intakes were higher in LGI compared with CHDR subjects (all P<0.05). Thus, in Asian post-GDM women with normal/higher INS, adding low-GI education to CHDR improved management of FBG and triglycerides.

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, glycaemic index, type 2 diabetes mellitus, prevention, fasting insulin, diet

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) increases the risk for metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus.1 To attenuate these risks, lifestyle intervention including components of diet, exercise and behavioural changes is recommended to post-GDM women to enable a moderate body weight loss of 7–10%.1 However, when compared with subjects with similar metabolic risks and glucose tolerance states, women with previous GDM achieve lower weight loss in response to standard recommendations and regain the weight lost rapidly.2 Subjects with hyperinsulinaemia, a condition commonly accompanying GDM, have a greater weight loss when on low-glycaemic-index (GI) diets.3, 4 Therefore, we analysed the effect of dietary GI on fasting blood glucose (FBG), serum lipids, body weight and body fat of post-GDM subjects with varying fasting serum insulin levels (INS) during weight loss.

Materials and methods

Seventy-seven post-GDM subjects, aged 20–40 years (mean±s.d.=30.5±9 years), without a current diagnosis of diabetes were recruited. The mean body mass index of the subjects at baseline was 26.4±4.6 kg m−2. Subjects were screened at a minimum of 2 months postpartum and the median duration since the last GDM delivery to the time of screening was 4 months (interquartile range 2). Mean parity among subjects was 2.0±1.1. Forty-four of the subjects had INS <2 μIU ml−1, which was below the detectable limits of the automated IMMULITE 2000 Systems, which was used for INS assay. The rest of the subjects had INS ⩾2 μIU ml−1 (range 2.43–28.6 μIU ml−1, with a median of 5.7 μIU ml−1). A fasting insulin value of 2 μIU ml−1 was chosen to be the cutoff to analyse the differential dietary effects, as it was approximately the natural median INS value for our subjects.

Twenty subjects with INS <2 μIU ml−1 (low INS) and 18 with INS ⩾2 μIU ml−1 (normal/high INS) were randomized to a group that only received conventional dietary recommendations (CHDR). CHDR education emphasised restriction of energy and fat intake and encouraged increase in dietary fibre intakes. Twenty-four subjects with INS <2 μIU ml−1 (low INS) and 15 with INS ⩾2 μIU ml−1 (normal/high INS) received low-GI education in addition to CHDR (LGI). A detailed account of the educational intervention used in this study has been published earlier.5 In brief, nutrition education was provided once at the baseline and take-home reference booklets were provided. Quarterly follow-up visits were scheduled. Fortnightly reminders reinforcing concepts of healthy living and motivating subjects to comply with the intervention were sent using email or short messaging services. Compliance was monitored through assessments of dietary intake, physical activity and nutrition knowledge assessment pertaining to the group-specific concepts. Frequency of subject contact was kept similar between groups. Subjects' self-reported and calculated adherence to dietary prescription was monitored. Low-GI education taught subjects to choose low-GI options for high-GI staples like bread, rice and so on. A 1500-kcal sample menu used in the two diet groups is presented in Table 1. The differences in FBG, serum lipids, body weight and body fat changes between the two dietary intervention groups among subjects differing in baseline INS were studied.

Table 1. Sample menu for the diet groups (∼1500 kcal).

| Meal | Timing (hours) | Sample menu low GI | Sample menu high GIa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | 0700 | Whole-grain bread—3 slices with baked beans Coffee/tea with 1/2 cup low-fat milk +1 tsp sugar | Tuna whole-meal bread sandwiches—3 slices of bread Tea (1 tsp sugar) |

| Morning snack | 1000 | 1 apple (medium size) | 1 slice watermelon (portion size to fit a small cup) |

| Lunch | 1230 | Noodles 1and1/2 cup with chicken or fish (1 match box size) (or) chappati (6′ dia, 2 nos)/+1/2 cup dhal Egg—1 medium Green vegetables salad—1 cup Orange—1 | White rice—1and1/2 cup Egg—1 medium Baked/steamed fish—1 piece Green vegetables salad—1 cup Banana—1 small |

| Afternoon snack | 1600 | 3 oatmeal biscuits/high calcium cream crackers Low-fat yoghurt—1 small tub | 3 Marie biscuits Tea (with 1 tsp sugar) |

| Dinner | 2000 | Parboiled/basmati rice—1 cup baked chicken/fish 1 piece (matchbox size) (or) spaghetti with meat sauce (1 cup) Salad—1 cup (use lettuce, cucumber, tomato, chick peas, peas, beans and lemon juice) | White rice—1 cup Baked chicken/fish—1 piece (matchbox size) Egg 1 medium Vegetable/salad—1cup (lettuce, cucumber, carrot, potato) |

Used for the conventional dietary recommendations (CHDR) group.

The study was approved by the Ethics and Review Committees of the institutions involved. Baseline INS was analysed using IMMULITE 2000 System (Siemens, Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL, USA). This insulin-automated assay had a coefficient of variation of 3%. Low INS samples were placed in the same category when the test results were duplicated. Blood glucose was measured using Cobas Integra 700 model (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) using the enzymatic reference Hexokinase/G6PD method. Serum lipids were measured using standard enzymatic colorimetric method and low-density lipoprotein was calculated. Body weight was measured in light clothing without footwear using digital weighing scales (Model: BWB-800A, Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Body fat was measured using the dual-emission X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA, Model: Delphi, Hologic Systems; Bedford, MA, USA). Dietary analysis was performed using a Malaysian diet intake calculator.6

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (version 19, Somers, NY, USA). The statistical significance standard was set at 5%. Data normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilks test. If data points were not normally distributed, statistical analysis was attempted on the natural logarithm of the values to improve the symmetry and homoscedasticity of the distribution. If the transformation was not successful, statistical analysis was carried out using non-parametric tests.

Effect size (ES) statistics were computed to study the magnitude of changes. ES values are typically computed to compare the effects of different treatments.7 ES provides a measure to assess the magnitude of difference between groups that cannot be obtained solely by focusing on P-values.8 P-values are dependent on both the magnitude of difference between groups and the sample size. Therefore, with other factors held constant, increasing the sample size increases the probability of finding a statistically significant difference.8 ES reported in this study was calculated as the ‘standardized' mean difference: that is, as a ratio between the mean change and s.d.of change.8 Individual ES values were calculated for changes in outcomes for each of the two diet groups and compared. ES values between 0.2–0.5, 0.5–0.8 and >0.8 were taken to denote ‘small', ‘moderate' and ‘large' changes in outcomes.7

Results and Discussion

The baseline characteristics of subjects randomized to the two diet groups in each INS stratum were comparable (see Table 2). A comparison of the outcome changes in the diet groups among subjects with low and normal/high INS levels is shown in Table 2. Among subjects with low INS, there were no significant differences in outcomes between the diet groups. After 1 year, normal/high INS subjects in the LGI group had a 2.2% reduction from baseline in FBG (−0.12±0.27 mmol l−1), whereas CHDR subjects had a 3.8% (0.17±0.32 mmol l−1) increase (P=0.025, see Table 2). In addition, normal/high INS subjects in the LGI group had a 12% reduction in triglycerides, whereas, in contrast, a 20% increase in triglycerides was noted in the CHDR group (−0.26±0.55 vs 0.19±0.54 mmol l−1, P=0.041, see Table 2). Changes in other serum lipids were not significantly different between the diet groups (see Table 2).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics and outcome changes in diet groups among subjects differing in fasting insulin levels (mean± s.d.).

| Outcome |

INS<2 μIU ml−1 |

INS⩾2 μIU ml−1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGI (n=24) | CHDR (n=20) | P-value | LGI (n=15) | CHDR (n=18) | P-value | |

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 31.2±4.2 | 31.0±3.8 | 0.892 | 31.5±5.2 | 31.8±5.1 | 0.863 |

| Parity | 2.1±1.1 | 2.0±1.2 | 0.721 | 2.1±1.2 | 2.2±1.21.0 | 0.801 ` |

| Duration postpartum (months) | 4.3±1.3 | 7.2±10.1 | 0.170 | 4.5±1.8 | 4.4±1.4 | 0.801 |

| Weight (kg) | ||||||

| Baseline | 61.7±10.2 | 57.9±10.1 | 0.221 | 71.1±11.3 | 72.1±10.6 | 0.807 |

| Change | −0.6±4.3 | −0.2±2.7 | 0.673 | −1.7±3.8 | −0.2±2.9 | 0.361 |

| Total body fat (kg) | ||||||

| Baseline | 23.2±6.8 | 22.3±6.7 | 0.673 | 28.6±7.2 | 29.8±7.1 | 0.643 |

| Change | 1.2±2.7 | 1.2±2.6 | 0.692 | 0.4±2.7 | 1.3±2.4 | 0.368 |

| Trunk fat (kg) | ||||||

| Baseline | 10.0±3.4 | 9.7±3.5 | 0.777 | 13.1±3.9 | 14.3±4.3 | 0.433 |

| Change | 0.75±2.1 | 0.6±1.5 | 0.798 | 0.2±1.5 | 0.7±1.4 | 0.252 |

| FBG (mmol l−1) | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.5±0.4 | 4.7±0.5 | 0.151 | 5.0±0.5 | 4.9±0.6 | 0.553 |

| Change | 0.48±1.2 | 0.18±0.32 | 0.155 | −0.12±0.27 | 0.17±0.32 | 0.025 |

| Total-cholesterol (mmol l−1) | ||||||

| Baseline | 5.0±0.98 | 5.3±0.81 | 0.366 | 5.2±0.7 | 5.2±0.77 | 0.808 |

| Change | −0.09±0.85 | −0.18±0.58 | 0.704 | −0.11±0.73 | −0.11±0.76 | 0.536 |

| Triglyceride (mmol l−1) | ||||||

| Baseline | 0.7±0.2 | 0.93±2.8 | 0.121 | 1.3±0.5 | 1.1±0.5 | 0.180 |

| Change | 0.16±0.43 | −0.08±0.34 | 0.075 | −0.26±0.55 | 0.19±0.54 | 0.041 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol l−1) | ||||||

| Baseline | 1.5±0.4 | 1.5±0.5 | 0.744 | 1.2±0.3 | 1.3±0.2 | 0.206 |

| Change | 0.04±0.3 | 0.04±0.2 | 0.978 | 0.1±0.18 | 0.01±0.31 | 0.283 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol l−1) | ||||||

| Baseline | 3.2±1.0 | 3.3±0.7 | 0.496 | 3.4±0.8 | 3.3±0.7 | 0.726 |

| Change | −0.23±0.66 | −0.18±0.41 | 0.796 | −0.1±0.54 | −0.21±0.57 | 0.573 |

| TC:HDL cholesterol | ||||||

| Baseline | 3.4±0.8 | 3.8±1.2 | 0.185 | 4.5±1.3 | 4.0±1.0 | 0.186 |

| Change | −0.14±0.43 | −0.26±0.37 | 0.360 | −0.52±0.87 | −0.1±0.60 | 0.113 |

| LDL:HDL cholesterol | ||||||

| Baseline | 2.2±0.75 | 2.4±0.96 | 0.279 | 3.0±1.1 | 2.6±0.79 | 0.241 |

| Change | −0.2±0.38 | −0.22±0.3 | 0.929 | −0.38±0.71 | −0.16±0.55 | 0.326 |

Abbreviations: CHDR, conventional healthy dietary recommendation group; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; INS, fasting insulin; LGI, low glycaemic index group; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Baseline variables were not significantly different between the diet groups among subjects in both insulin strata.

P-values shown are calculated from independent tests for difference between the diet groups, within individual insulin groupings.

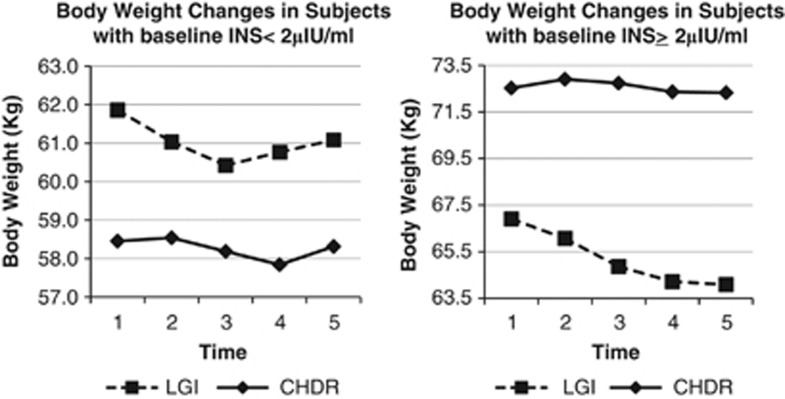

Among subjects with baseline INS ⩾2 μIU ml−1, weight loss (LGI vs CHDR: −1.7±3.8 vs −0.16±2.9 kg, ES=0.47 vs 0.08, P=0.361) and changes in total body fat (g) (LGI vs CHDR: 0.37±2.7 kg, ES=0.14 vs 1.5±2.8 kg, ES=0.53; P=0.37) were not significantly different. These observations suggest beneficial effects of low-GI diets in the management of body weight and composition among normal/high INS subjects, although it is emphasised that the study is not statistically powered to evaluate these outcomes. However, these observations are consistent with the 6 months finding from the CALERIE study, which reported that women with postprandial hyperinsulinaemia lost more weight on low-GI diets after 6 months on intervention.4 The observations from this study are also in agreement with the findings of Ebbeling et al.,9 who showed that subjects with higher insulin levels (⩾57.5 μIU ml−1 at 30 min after a 75-g dose of oral glucose) lost significantly higher amounts of body weight and body fat loss when on low-glycaemic-load diets as compared with conventional low-fat diets. Also, weight regain that is commonly observed after weight loss in trials of duration >6 months was absent among these normal/high-INS Asian subjects in the LGI arm of the current study (see Figure 1). A similar observation was noted among hyperinsulinaemic obese young adults (aged 18–35 years) studied in Boston.9

Figure 1.

Changes in body weight among subjects with varying baseline fasting insulin levels (estimated marginal means, kg). Legend: panel on the left plots weight changes in subjects with baseline fasting insulin <2 μIU ml−1. Panel on the right plots weight changes in subjects with baseline fasting insulin ⩾2 μIU ml−1. Dotted line shows weight changes in LGI. Smooth line shows weight changes in CHDR. Time points 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 refer to body weight at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after intervention.

Baseline dietary intakes were similar between groups among all subjects. Among subjects with both INS levels, reported dietary intakes varied significantly only in terms of diet GI and dietary fibre content after intervention (see Table 3). In all subjects, estimated diet GI was lower and reported dietary fibre intakes were higher in LGI as compared with CHDR subjects (all P<0.05). In subjects with low INS, calculated diet GI means±s.d. in the LGI and CHDR groups were 59±4 and 65±4, respectively (P<0.001). Their estimated dietary fibre intakes were 12±3 vs 16±4 g, respectively (P=0.004). Among subjects with normal/high INS mean (s.d.) calculated diet GI means (s.d.) in the LGI and CHDR groups were 56±4 and 62±6, respectively (P<0.021). Their estimated dietary fibre intakes were 13±5 vs 17±4 g, respectively (P=0.045).

Table 3. Dietary intake among subjects after the intervention (mean±s.d.)a.

| Dietary intake |

INS<2 μIU ml−1 |

INS⩾2 μIU ml−1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGI | CHDR | P-value | LGI | CHDR | P-value | |

| Energy (kcal) | 1706±351 | 1595±298 | 0.298 | 1554±292 | 1595±442 | 0.927 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 221±46 | 221±55 | 0.975 | 186±62 | 208±48 | 0.331 |

| Protein (g) | 68±15 | 60±13 | 0.086 | 70±11 | 67±28 | 0.259 |

| Fat (g) | 59±17 | 51±11 | 0.093 | 50±10 | 55±20 | 0.977 |

| Dietary fibre (g) | 17±4 | 13±3 | 0.004 | 17±4 | 13±5 | 0.048 |

| Glycaemic index | 59±4 | 65±4 | <0.001 | 56±4 | 62±6 | 0.021 |

| Glycaemic load | 130±29 | 145±41 | 0.195 | 113±38 | 128±28 | 0.244 |

Abbreviations: CHDR, conventional healthy dietary recommendation group; LGI, low glycaemic index group.

Baseline dietary intakes were not significantly different between the diet groups for subjects in both insulin strata.

P-values shown are calculated from independent tests for difference between the diet groups, within individual insulin groupings.

The values shown are an average of the dietary data obtained using 3-day food records, during the quarterly visits during the 1-year trial period.

We acknowledge that 2 μIU ml−1 is very low as a cutoff to suggest fasting hyperinsulinaemia. As published earlier by this research group, data on the normal fasting insulin range for young healthy Malaysian women are currently unavailable.10 A small Malaysian study found a median fasting insulin level of 4.7 μIU ml−1 with a central 95% range of 2.1–12.1 μIU ml−1 among 30 healthy volunteers (including 12 females).11 This preliminary study also observed that the range for fasting insulin in their group of Malaysian subjects was lower than the 95% CI of 6–29 μIU ml−1 typically reported.11 Our study did demonstrate similarly low fasting INS levels as reported in a small pilot study among Austrian GDM women (n=10), at 3 months postpartum.12 This study reported a median fasting insulin level of 1.63 μIU ml−1.12 Furthermore, lactation is associated with lower levels of INS at 6–9 weeks postpartum.13 However, in this study, only 12 out of 77 subjects (<16%), recruited at a median of 4 months postpartum, were reportedly breastfeeding.

This study demonstrated significant lowering of FBG and TG in post-GDM women with baseline fasting insulin >2 μIU ml−1 who received iso-caloric LGI diets in comparison with those on conventional low-fat diets. These observations are corroborated by earlier findings that suggest that dietary GI may have varying effects depending on individual metabolic phenotypes.14 As FBG is considered to be the strongest predictor of development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with previous GDM,15 a reduction in FBG by lowering dietary GI may translate to added clinical benefits of lowering diabetes risk among these women with normal or higher insulin levels. Moreover, triglycerides increase cardiovascular disease risk to a higher extent in women than in men.16, 17 Therefore, LGI diets may also be considered cardio-protective to post-GDM women with normal to higher insulin levels.

The favourable anthropometric and glycaemic responses to low GI intervention seen in those with higher insulin levels, in comparison with subjects with low baseline insulin levels, could possibly be explained by the exaggerated glycaemic responses to increase in diet GI among high/normal INS subjects as compared with the low INS subjects. Asian subjects known to demonstrate insulin resistance at much lower body weight and waist circumference18 could have exaggerated postprandial glycaemic response to carbohydrate foods even while presenting fasting insulin levels that are typically considered as being ‘normal'.

Hence, even though a 15% difference in dietary GI between the groups (about 9 units based on baseline GI), thought to have clinical significance,19 could not be achieved after 12 months of intervention, significant differences in FBG and TG were seen among subjects with high/normal INS levels. Nevertheless, it is also interesting to observe that much smaller differences in the GI (among the quintiles compared in observational studies), than the 10 GI unit difference thought to be of clinical significance,19, 20 show significant reductions in cardio-metabolic risks.21, 22, 23, 24 Differences in dietary GI as low as five units have shown significant trends for improvements in high-density lipoprotein and hs-CRP.23, 25 Lower trends for fasting insulin are seen at around seven units,22 and lower insulin resistance at three unit differences in GI24 in a few of these observational studies. Furthermore, shorter Asian trials of 6 months duration, achieving a difference in GI of ≈6 units between groups, have also documented significant beneficial effects in terms of reductions in waist circumference, FBG and glycaemic control in diabetic subjects or those with impaired fasting glucose.26, 27 Longer trials lasting until a year have found favourable changes in cardio-metabolic risks in the low GI/GL groups when the difference in GI established between the groups was comparable to the six-unit difference documented in the current study.28, 29 A decrease in triglycerides was documented when a seven-unit difference in GI was established among obese young adults.28 Similarly, improvements in insulin sensitivity have been documented when a six-unit GI difference was established between two groups of PCOS women.29 The findings from this study therefore extend the application of an existing body of evidence that indicates that low-GI diets may have added benefits in cardio-metabolic risk management in hyperinsulinaemic subjects4, 9, 30 among normal and hyperinsulinaemic Asian subjects.

These findings lend credence to translational research with practical approaches to lowering dietary GI, when the ‘free-living conditions' of the subjects may hamper the achievement of marked diet GI reduction seen in controlled clinical trials. Further investigation of the interaction between insulin levels and response to diet GI is necessary. Such an effort may also help clarify the inconclusive associations reported between GI and risk for chronic diseases.

The small sample size limits generalisation of the results to other populations. Furthermore, INS <2 μIU ml−1 was not quantifiable by the assay used. Hence, caution is needed while interpreting these data. Also, the current trial monitored fasting insulin levels and not postprandial insulin, which could have demonstrated more apparently the exaggerated insulin response typical in early pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nevertheless, an increase in fasting insulin concentration is also associated with hyperinsulinaemia.31

Conclusion

Thus, in Asian women with a history of GDM, having normal or higher fasting INS, adding low-GI education to conventional dietary guidelines improved management of FBG and triglycerides. More research on the interaction between insulin levels and response to diet GI is necessary.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by an internal research grant (IMU199/2009) from International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, de Leiva A, Dunger DB, Hadden DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-conference on gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:S251–S260. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratner RE, Christophi CA, Metzger BE, Dabelea D, Bennett PH, Pi-Sunyer X, et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4774–4779. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sichieri R, Moura AS, Genelhu V, Hu F, Willett WC. An 18-mo randomized trial of a low-glycemic-index diet and weight change in Brazilian women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:707–713. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittas AG, Das SK, Hajduk CL, Golden J, Saltzman E, Stark PC, et al. A low-glycemic load diet facilitates greater weight loss in overweight adults with high insulin secretion but not in overweight adults with low insulin secretion in the CALERIE trial. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2939–2941. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyam S, Arshad F, Ghani RA, Wahab NA, Safii NS, Yusof BNM, et al. Lowering dietary glycaemic index through nutrition education among malaysian women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Mal J Nutr. 2013;19:9–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyam S, Kock Wai TNG, Arshad F. Adding glycaemic index and glycaemic load functionality to DietPLUS, a Malaysian food composition database and diet intake calculator. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2012;21:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Johri S, Saxena AM. Diabetes mellitus: the pandemic of 21st century! Asian J Exp Sci. 2009;23:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:917–928. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbeling CB, Leidig MM, Feldman HA, Lovesky MM, Ludwig DS. Effects of a low-glycemic load vs low-fat diet in obese young adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2092–2102. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.19.2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyam S, Arshad F, Abdul Ghani R,A, Wahab N, Safii NS, Barakatun Nisak MY, et al. Low glycaemic index diets improve glucose tolerance and body weight in women with previous history of gestational diabetes: a six months randomized trial. Nutr J. 2013;12:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi A, Tariq A. Preliminary human fasting plasma insulin values by using immulite kit. Int Med J Malaysia (Online) 2011;1 [Google Scholar]

- Farhan S, Handisurya A, Todoric J, Tura A, Pacini G, Wagner O, et al. Fetuin-A characteristics during and after pregnancy: result from a case control pilot study. Int J Endocrinol. 2012;2012:896736. doi: 10.1155/2012/896736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EP, Hedderson MM, Chiang V, Crites Y, Walton D, Azevedo RA, et al. Lactation intensity and postpartum maternal glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in women with recent GDM: the SWIFT cohort. Diabetes Care. 35:50–56. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Rosenberg L, Singer M, Hu FB, Djousse L, Cupples LA, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and cereal fiber intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in US black women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2304–2309. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1862–1868. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensvold I, Tverdal A, Urdal P, Graff-Iversen S. Non-fasting serum triglyceride concentration and mortality from coronary heart disease and any cause in middle aged Norwegian women. BMJ. 1993;307:1318–1322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokanson JE, Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride level is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level: a metaanalysis of population-based prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1996;3:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the national heart, lung, and blood institute/american heart association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:e13–e18. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff LM, Frost GS, Hamilton G, Thomas EL, Dhillo WS, Dornhorst A, et al. Carbohydrate-induced manipulation of insulin sensitivity independently of intramyocellular lipids. Br J Nutr. 2003;89:365–374. doi: 10.1079/BJN2002789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay AW, Petocz P, McMillan-Price J, Flood VM, Prvan T, Mitchell P, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risks- a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:627–637. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. New Engl J Med. 2001;345:790–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano Y, Kawakubo K, Lee JS, Tang AC, Sugiyama M, Mori K. Correlation between dietary glycemic index and cardiovascular disease risk factors among Japanese women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1472–1478. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Manson JE, Buring JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Ridker PM. Relation between a diet with a high glycemic load and plasma concentrations of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:492–498. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toeller M, Buyken AE, Heitkamp G, Cathelineau G, Ferriss B, Michel G, et al. Nutrient intakes as predictors of body weight in European people with type 1 diabetes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1815–1822. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Holmes MD, Hu FB, Hankinson SE, et al. Dietary glycemic load assessed by food-frequency questionnaire in relation to plasma high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and fasting plasma triacylglycerols in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:560–566. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusof BNM.A Randomized Control Trial of Low Glycemic Index against Conventional Carbohydrate Exchange Diet on Glycemic Control and Metabolic Parameters in Type 2 Diabetes Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur; 2008. p407 [Google Scholar]

- Amano Y, Sugiyama M, Lee JS, Kawakubo K, Mori K, Tang AC, et al. Glycemic index-based nutritional education improves blood glucose control in Japanese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1874–1876. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbeling CB, Leidig MM, Sinclair KB, Seger-Shippee LG, Feldman HA, Ludwig DS. Effects of an ad libitum low-glycemic load diet on cardiovascular disease risk factors in obese young adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:976–982. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann SE, McCann WE, Hong CC, Marshall JR, Edge SB, Trevisan M, et al. Dietary patterns related to glycemic index and load and risk of premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer in the Western New York Exposure and Breast Cancer Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:465–471. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulian G, Rusu E, Dragomir A, Posea M. Metabolic effects of low glycaemic index diets. Nutr J. 2009;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan-Pidhainy X. Postprandial Metabolic Responses to Macronutrient in Healthy, Hyperinsulinemic and Type 2 Diabetic Subjects. Graduate Department of Nutritional Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto: Toronto; 2011. [Google Scholar]