Abstract

The formation of signalling boundaries is one of the strategies employed by the Notch (N) pathway to give rise to two distinct signalling populations of cells. Unravelling the mechanisms involved in the regulation of these signalling boundaries is essential to understanding the role of N during development and diseases. The function of N in the segmentation of the Drosophila leg provides a good system to pursue these mechanisms at the molecular level. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of the N ligands, Serrate (Ser) and Delta (Dl) generates a signalling boundary that allows the directional activation of N in the distalmost part of the segment, the presumptive joint. A negative feedback loop between odd-skipped-related genes and the N pathway maintains this signalling boundary throughout development in the true joints. However, the mechanisms controlling N signalling boundaries in the tarsal joints are unknown. Here we show that the non-canonical tarsal-less (tal) gene (also known as pri), which encodes for four small related peptides, is expressed in the N-activated region and required for joint development in the tarsi. during pupal development. This function of tal is both temporally and functionally separate from the tal-mediated tarsal intercalation during mid-third instar that we reported previously. In the pupal function described here, N signalling activates tal expression and reciprocally Tal peptides feedback on N by repressing the transcription of Dl in the tarsal joints. This Tal-induced repression of Dl is mediated by the post-transcriptional activation of the Shavenbaby transcription factor, in a similar manner as it has been recently described in the embryo. Thus, a negative feedback loop involving Tal regulates the formation and maintenance of a Dl+/Dl− boundary in the tarsal segments highlighting an ancient mechanism for the regulation of N signalling based on the action of small cell signalling peptides.

Keywords: Notch signalling, leg segmentation, tarsus, joints, Tarsal-less, Shavenbaby, small ORFs, small peptides

Introduction

The organisation of cells in complex tri-dimensional structures relies to a great degree on efficient communication between cells. Cell-cell interactions coordinate patterns of cell division, survival, migration and differentiation, giving rise to the formation of the final organ. Despite the vast variety of cell types and cell communication events, only a small number of cell signalling pathways have been characterised. One of these is the Notch (N) pathway, which consists of a single transmembrane receptor , N, that is activated by binding to the transmembrane DSL ligands (named after Delta (Dl), and Serrate (Ser) and LAG-2) from the neighbouring cells (Bray, 2006; Fleming et al., 1997). Upon binding the N receptor undergoes two consecutively proteolytic cleaves by the ADAM-metalloprotease and γ-secretase complexes respectively, releasing the N intracellular domain (Nicd)(Bray, 2006; Fortini, 2009). Consequently, the Nicd translocates into the nucleus where it binds to the CSL (named after CBF1, Su(H) and LAG-1) transcriptional complex and activates the transcription of target genes (Bailey and Posakony, 1995; Bray, 2006; Lecourtois and Schweisguth, 1995).

The fundamental role of the N pathway in different developmental processes from lateral inhibition to formation of patterning boundaries is to control cell fate choices between neighbouring cells (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 1999; Bray, 2006). N-mediated cell fate determination relies on the differential expression of ligand and receptor in opposing cells. This differential distribution, between ligand in the signal cell and receptor in the responsive cell, is accomplished by a negative feedback loop by N signalling that represses ligand expression in the responsive cell (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 1999; Fortini, 2009). Reciprocally, ligand expressing cells lose their own ability to respond to Notch, by transcriptional or post-transcriptional repression of N (Becam et al., 2010; Fortini, 2009; Miller et al., 2009). Thus, feedback loops amplify and reinforce the differential distribution of the ligand and the receptor giving rise to different cell fates within a population of competent cells. It appears that these feedback loop mechanisms controlling N signalling differ depending on the developmental context (Heitzler et al., 1996; Huppert et al., 1997). Therefore, unravelling these mechanisms is key to understanding how N signalling regulates these developmental processes, and hence diseases where N signalling is deregulated, such as cancer (Rizzo et al., 2008; Roy et al., 2007; Stylianou et al., 2006; Weng et al., 2004).

The legs of Drosophila are a good system in which to study N signalling as the genetic cascade controlling leg development and the subsequent morphogenesis is well understood (Fristrom and Fristrom, 1993; Galindo and Couso, 2000; Kojima, 2004; Manjon et al., 2007; Mirth and Akam, 2002). Drosophila legs are composed of segments separated by flexible specialized structures called joints (Fig. 1A) (Fristrom and Fristrom, 1993). There are two types of joints according to their structure and function (Bishop et al., 1999; Fristrom and Fristrom, 1993; Mirth and Akam, 2002; Tajiri et al., 2010): the true joints, which correspond to the coxa, trochanter, femur and tibia segments and pretarsus, are attached by muscles and each one has a unique morphology (Fig. 1E); the joints of the tarsal segments have an identical ball and socket structure and do not develop muscle attachments (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1. Tal is required for joint development in the tarsal segments.

A- Pupal leg (4h after puparium formation (APF)) showing stripes of tal mRNA expression in the tarsus (arrowheads). The leg is starting to evert; distal to the right.

B- tal mRNA localisation in a pupal leg at 6h APF. tal is expressed in the distal part of the tarsal (t1-t4) segments (arrowheads) near the joint constrictions.

C- Distal part of a tal-lacZ pupal leg (8h APF) showing strong tal expression in the distalmost part of the tarsal segments.

D- D′′- Everted pupal leg (8h APF) showing tal mRNA (green, arrowhead) and bib-lacZ (red) expression patterns. bib-lacZ and tal mRNA are expressed adjacent to each other in the distalmost part of the tarsal segments. (D′) red channel showing bib-lacZ expression. (D′′) tal mRNA expression (arrowhead).

E- Leg of a wild-type fly, showing the true segments (Coxa (Co), Trochanter (Tr), Femur (Fe), Tibia (Tb) and Pretasus (c)), and the tarsal segments (Ta).

F- Distalmost part of a wild-type leg showing the tarsal segments (t1-t5) separated by naked joint tissue. Inset denotes the stereotypical ball and socket tarsal joint (arrowhead). Proximal to the top, distal to the bottom.

G- Tarsal region of a bab-Gal4;UAS-dstal leg. The tarsal segments are misshapen, lacking joints (arrowheads).

H- tal null clone induced between 96-120h AEL that runs along the ventral part of the tarsi marked with forked (blue). Note that every tarsal segment is still present.

I- High magnification of H. In the tal null homozygous clone the joints do not form (arrowheads). However, some forked mutant bristles lacking tal can form part of remaining joint structures, revealing the non-autonomous nature of tal function (arrows).

J- bab-Gal;UAS-tal tarsi showing ectopic joint structures (arrows) adjacent to the proper joint (arrowheads).

Leg segmentation and subsequent joint development are controlled by the spatially regulated activation of the N signalling pathway and its ligands (Bishop et al., 1999; de Celis et al., 1998; Rauskolb and Irvine, 1999). During leg development a complex regulatory gene network of proximodistal (PD) patterning genes induces the activation of Ser and Dl expression in the distalmost region of each segment just proximal to the presumptive joint region (Rauskolb, 2001; Shirai et al., 2007; St Pierre et al., 2002). Different regulators such as Fringe and the PCP (Planar Cell Polarity) and Ras pathways are involved in restricting Ser and Dl signalling to the distal side of the Dl and Ser expression domains, generating a signalling boundary (Bishop et al., 1999; de Celis et al., 1998; Galindo et al., 2005; Shirai et al., 2007). The activation of downstream genes, such as activator protein-2 (AP-2), Enhancer of Split complex (E(spl)), disconnected and big brain (bib) in these distal cells initiates the joint developmental programme (Bishop et al., 1999; de Celis et al., 1998; Kerber et al., 2001). Maintaining the spatial asymmetry between ligand expression and N activation is vital for leg segmentation, as ectopic expression of ligands in the N responsive region represses joint formation through post-transcriptional down regulation of N (Bishop et al., 1999; Rauskolb and Irvine, 1999).

It has been shown that sharp N signalling boundaries in the true joints are maintained by a negative feedback loop between the N signalling pathway and the “odd-skipped (odd)-related” drumstick (drm)-lines-bowl genes cassette (Greenberg and Hatini, 2009). In cells expressing Dl, the Lines protein is active and nuclear leading to the destabilisation of the Bowl protein and its subsequent degradation (Greenberg and Hatini, 2009; Hatini et al., 2005). In the adjacent joint cells, N signalling activates the expression of drm, and as a result the Drm protein binds to Lines thus preventing Bowl degradation; consequently, Bowl can accumulate in the nucleus where it represses Dl expression (Greenberg and Hatini, 2009). This elegant mechanism reinforces a Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary and ensures its maintenance through joint development. Although AP-2 contributes also to the repression of DSL ligands in the true joints, possibly in parallel to the Drm-Lines-Bowl mechanism, and in the tarsal joints (Ciechanska et al., 2007), it appears that there must be other, currently unknown, factors contributing to the generation and maintenance of the Dl+/Dl− boundary in the tarsal segments in an analogous way to the drm-lines-bowl cassette at work in true segments (Ciechanska et al., 2007).

Here we show that the non-canonical tarsal-less (tal) gene (also known as polished rice) is the crucial factor for the establishment and maintenance of a Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary in the tarsal joints. tal produces a single polycistronic transcript that encodes for several small related peptides required for the development of embryonic ectodermal structures, such as the denticle belts and trachea and also for leg tarsal development (Galindo et al., 2007; Kondo et al., 2007; Pueyo and Couso, 2008). Interestingly, the 11 amino acid long Tal peptides act non-autonomously in each developmental context explored, indicating that Tal peptides could be a new type of cell signal (Kondo et al., 2007; Pueyo and Couso, 2008). A recent study on the function of Tal during denticle formation has revealed that Tal peptides are able to switch the Shavenbaby (Svb) transcription factor, a master protein involved in denticle formation, from a repressor to an activator (Kondo et al., 2010; Payre, 2004). This change in behaviour of Svb is associated with a change in its nuclear distribution; the Svb repressor form is localised in nuclear foci, whereas the Svb activator appears diffused throughout the nuclei. Tal triggers Svb activation by the induction of a post-translational modification of Svb, giving rise to an amino-terminal end (Nt) truncated Svb short form which is similar to the germline Svb short variant OvoB. Although Tal peptides control the activation of Svb and denticle formation, it is important to note that other Tal functions during embryonic development are independent of Svb (Kondo et al., 2010).

In this report we show that tal is expressed in the N responsive region of the tarsal joints and is required for their development. Dl signalling activates tal expression in adjacent cells and subsequently Tal peptides repress Dl expression in these cells, generating a sharp signalling boundary. Tal mediated repression of Dl is achieved through the post-transcriptional activation of the Svb transcription factor. Therefore, a negative feedback loop involving Tal regulates the formation and maintenance of a Dl+/Dl− border. Thus, our work highlights a new mechanism for the regulation of N signalling, based on the action of small cell signalling peptides.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks and genetics

Drosophila stocks were raised at 25°C on standard cornmeal/agar/yeast medium. The following fly strains have been used: tal-lacZ, talS18 FRT82B (Galindo et al., 2007), UAS-dstal (this work); svbP107-lacZ, y svbR9 FRT19A, UAS-ovoB, UAS-svb, UAS-ovoD (Delon et al., 2003); UAS-Svb-GFP (Kondo et al., 2010); Nts, Df(3)Dl Bx12, UAS-Nintra, UAS-Necd and UAS-Dl (Bishop et al., 1999); bibE1-lacZ, Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ (Furriols and Bray, 2001) and E(spl)mβ1.5-lacZ (Cooper et al., 2000). The following Gal4 lines dpp-Gal4, omb-Gal4, bab-Gal4, ptc-Gal4, Dll-Gal4 were used for ectopic expression (Brand and Perrimon, 1993) and their expression patterns described in Galindo et al., 2007 and Pueyo and Couso 2008. Several lines carrying FRT chromosomes have been used: w hsFLP122 Ubi-RFP FRT19A; y w f36a hsFLP122 ;M(3) f+(w+)FRT82B/TM6B (G.Bellido); w hsFLP122;M(3) Ubi-GFP FRT82B/TM6B.

For induction of clones we have utilized the FRT/FLP system (Xu and Rubin, 1993). For talS18 loss of function clones, larvae were heatshocked for 45min at 37°C between 96-120h after egg laying (AEL). svbR9 loss of function clones where induced as above between 48-72h AEL. Gain of function flip-out clones were generated by crossing different UAS lines to y w hsFLP122; Act5>y+>Gal4; UAS-GFP cassette and heatshocking the offspring for 20min at 37°C at 96-110h AEL.

The Nts temperature-sensitive allele was crossed to null alleles and then shifted from the permissive temperature 18°C to the restrictive temperature 25°C at 96-110h AEL to give rise to individuals with almost total loss of function in the tarsi (Bishop et al., 1999).

Generation and expression of double stranded tal construct (dstal)

A 400pb fragment corresponding to the 5′UTR of the tal transcript was amplified by PCR using the following primers: dstalF 5′CACCTGCAGATCACCAGCTAAAAGAAA3′ and dstalR 5′CGTATGCCGTGTATTGACCAAAAATAC3′. The PCR fragment was cloned between the attL1 and attL2 recombination sites in the pENTR-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Subsequently, in vitro recombination using the LR clonase (Invitrogen) was induced between the pENTR-dstal-TOPO vector and the pRISE-ftz vector with two inverted sequences flanked by the attR1 and attR2 recombination sites separated by the ftz intron (Kondo et al., 2006). Selection of the colonies with the appropriate pRISE-dstal vector was performed as described in Kondo et al., 2006. The efficiency of the dstal construct in knocking down tal expression was tested in S2R+ cells by monitoring the Tal1A-GFP expression in S2R+ cells transfected with the pRISE-dstal construct (Suppl. Fig. 1F,G; Galindo et al., 2007). Transgenic flies carrying the pRISE-dstal construct were generated following standard procedures (Vanedis injection Service).

To knock down tal function in flies we expressed the UAS-dstal constructs together with the UAS-Dicer constructs as Dicer over-expression makes more efficient the production of small double-stranded RNAs.

Immunocytochemisty, in situ hybridisation and microscopy

Pupae at the appropriate stage were collected and dissected as described in Bishop et al., 1999. Standard procedures for immunohistochemistry were followed and the following antibodies were used: mouse anti-AP2 (Kerber et al., 2001), mouse anti-Dl (DSHB), rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (Cappel). For detection of the Svb-GFP with have used rabbit anti-GFP (Molecular Probes) and we have amplified the signal using tyramide signal amplification system (Perkin Elmer) (Kondo et al., 2010). Secondary antibodies conjugated to different fluorophores were used to 1:100 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). DAPI (Invitrogen) has been used to label nuclei. Standard protocol for in situ hybridisation was followed with minor changes (Galindo et al., 2005). For the fluorescent in situ hybridisation and antibody assays we followed the standard in situ protocol with the following changes. The proteinase K treatment step was avoided and replaced by a hot hybridisation step at 72°C in Hybrix solution. After hybridisation washes we proceed with the standard immuno-staining protocol. The DIG-labelled probe was detected with anti-DIG antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Roche) followed by tyramide signal amplification reaction (Perkin Elmer). The labelled Dl riboprobe was synthesised by digesting Dl LD21369 pOT2 construct (DGRC) with EcoRI restriction enzyme and using it as a template for the Sp6 promoter RNA synthesis with DIG labelled ribonucleotides (Roche). For the svb riboprobe, Svb LD47350 pOT2 construct (DGRC) digested with EcoRI restriction enzyme was used as a template for Sp6 RNA production and labelled as above. Images were acquired with a Leica DRBM microscope and a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope, and processed with QWin, LMS and Photoshop software.

Results

1- Tarsal-less is required non-autonomously for tarsal joint development.

We have previously shown that tal has a role in the determination of the presumptive tarsal region in early third instar larvae (Galindo et al., 2007; Pueyo and Couso, 2008). At this time, a single domain of tal expression is intercalated between the expression domains of the dachsund (dac) and Bar (B) genes. Next Tal represses B and dac through the activation of the Rotund (Rn) and Spineless (Ss) transcription factors, thus generating a new territory of presumptive tarsal cells defined by the presence of Rn and Ss and the absence of Dac and B. (Pueyo and Couso, 2008). We have identified a new role for tal in later stages of leg development. During early pupal development, both tal mRNA and tal-lacZ reporter are expressed in stripes of cells in the distal part of each tarsal segment (Fig.1 A-C). These stripes of cells correspond to the joint region because tal expression is distally adjacent to the expression of the N target gene bib (Fig. 1D-D′′), which identifies the proximal side of the presumptive (de Celis et al., 1998; Galindo et al. 2005).

To characterise Tal function during joint development without disrupting its earlier function we have performed mosaic analysis. In legs with tal loss of function clones induced after tarsal intercalation, all the tarsal segments are present indicating that tarsal intercalation has proceeded normally (Fig. 1H-I). However, these clones are not phenotypically normal, as no joint structures are formed in the middle of large clones covering the distal part of the tarsal segments (Fig. 1I). Joint loss is prefigured in the developing pupal legs by the loss of bib-lacZ reporter which is a marker of joint cell fate (Fig. 2A-A′,B-B′) (de Celis et al., 1998; Shirai et al., 2007). As in other developmental contexts tal acts non-autonomously, some tal mutant cells develop joint structures (Fig. 1E). Similarly, bib-lacZ expression can be observed in tal mutant cells, which are up to 3-4 cell diameters away from the tal-expressing cells, but it is lost in tal mutant cells located further away (Fig. 2B-B′). These observations are in agreement with the non-autonomous range of action of Tal peptides in other developmental processes (Kondo et al., 2007; Pueyo and Couso, 2008).

Figure 2. Tal regulates N target genes non-autonomously in the tarsal joint.

A- A′- Expression of the joint marker bib-lacZ (red) in the tarsal region covered by Bab protein (green) in a pupal leg (6h APF) (A). bib-lacZ expression is limited to a single row of cells in the distal part of the tarsal segments (A′).

B- B′- Distal part of a bib-lacZ pupal leg (5h APF) containing Minute+ GFP−, tal− null clones. GFP expression labels the tal+ tissue. bib-lacZ expression (red) is absent in the middle of a large tal mutant clone (brackets). Note that tal acts non-autonomously in bib-lacZ regulation (arrowhead) (B). Expression of bib-lacZ (B′).

C- C′- A bib-lacZ (red) pupal leg (5h APF) expressing UAS-dstal in the tarsi using the bab-Gal4 driver (green) (C). Strong reduction of the bib-lacZ reporter is observed (arrows) (C′).

D- D′- Ectopic joints in a bab-Gal4;UAS-tal pupal leg (6h APF) showing Bab (green) and bib-lacZ (red) patterns of expression (D). A duplicated row of bib-lacZ expressing cells is observed (arrowhead: endogenous; arrow: ectopic) (D′).

E- E′- tal gain of function clones (green) induce ectopic expression (arrow) of the bib-lacZ reporter (red) in the distal part of the first tarsal segment (E). bib-lacZ expression (E′).

To further prove the essential role of Tal peptides in tarsal joint development we have expressed a tal construct that produces double stranded tal RNA, which efficiently knocks out tal expression in the tarsus using the Dll-Gal4(not shown;(Calleja et al., 1996)) and bab-Gal4 (Cabrera et al., 2002) drivers (Suppl. Fig. 1A-A′′, D, E). In these UAS-dstal RNAi flies, the tarsal segments are misshapen and lack joint structures and they also exhibit necrotic tissue and ectopic bristles (Fig. 1G and Suppl. Fig. 1C). In addition, a significant reduction of bib-lacZ expression can be observed in tarsal segments in the bab-Gal4;UAS-dstal pupal legs (Fig. 2C-C′). Altogether these results show that tal is required for tarsal joint development.

To define the role of tal in joint development further, we mis-expressed tal in the tarsal region. Ectopic tal expression throughout the tarsi produces extra joint structures proximal to the endogenous ones (Fig. 1J and Suppl. Table 1). In pupal bab-Gal4;UAS-tal legs, a proximal ectopic stripe of cells expressing bib-lacZ or AP-2 can be observed (Fig. 2D-D′; Suppl. Fig. 2A-A′′,B-B′′). Induction of ectopic joints is not a consequence of the early role of tal in regulating B and dac genes since the expression patterns of these genes are not affected (Suppl. Fig. 2 G-G′′,H-H′′). Similarly, tal gain of function clones are only able to activate bib-lacZ ectopically proximal to the joint, in a non-autonomous manner (Fig. 2E-E′). Thus, Tal-mediated induction of ectopic joints seems to require a factor(s) located in the cells proximal to the endogenous joint.

2- Tal function requires N signalling during tarsal joint formation

The formation of the joints depends on a complex gene interaction network that ensures N signalling activation in the distalmost part of the segment (Bishop et al., 1999; de Celis et al., 1998; Galindo et al., 2005; Shirai et al., 2007). Given that tal is expressed and required in the N responsive domain, and that tal induces ectopic joints in the region proximal to the endogenous joints where N ligands are expressed (Bishop et al., 1999; de Celis et al., 1998; Rauskolb and Irvine, 1999), we have searched for genetic interactions between tal and N signalling during joint formation.

To test whether tal is a downstream target of N signalling in tarsal joints first we used Nts thermosensitive mutants shifted to the restrictive temperature before tarsal segmentation takes place at the end of third larval instar. The tarsal joints do not form in these Nts mutants (Suppl. Fig. 1B; Bishop et al., 1999) and this is correlated with the loss of bib-lacZ expression (Fig. 3A-A′). Similarly, tal-lacZ expression is lost from the Nts mutant tarsal joints (Fig. 3B-B′) indicating that N signalling is required for tal expression. Next, we ectopically expressed a N dominant negative form (Necd) that knocks out N signalling, using the omb-Gal4 driver, which is expressed in the dorsal part of the pupal legs. As a result, these flies have deformed legs with incomplete joints (not shown) and tal-lacZ expression is lost or reduced in the dorsal part of the pupal legs (Fig. 3C-C′). Thirdly, we activated the N pathway by ectopically expressing the constitutively active form of Notch (Nicd) or its ligand Dl. Ectopic expression of Dl or Nicd using the ptc-Gal4 driver or in flip-out clones induced ectopic tal-lacZ expression (Fig. 3D-D′; Suppl. Fig. 3A-A′) and flies with shorter legs and ectopic joints (not shown). Importantly, N-mediated activation of tal expression is limited to this developmental stage since ectopic expression of Nicd or Dl in mid third instar leg discs does not induce ectopic tal-lacZ expression (Suppl. Fig. 3B-B′, C-C′). Altogether these results indicate that N signalling activates tal expression during joint development.

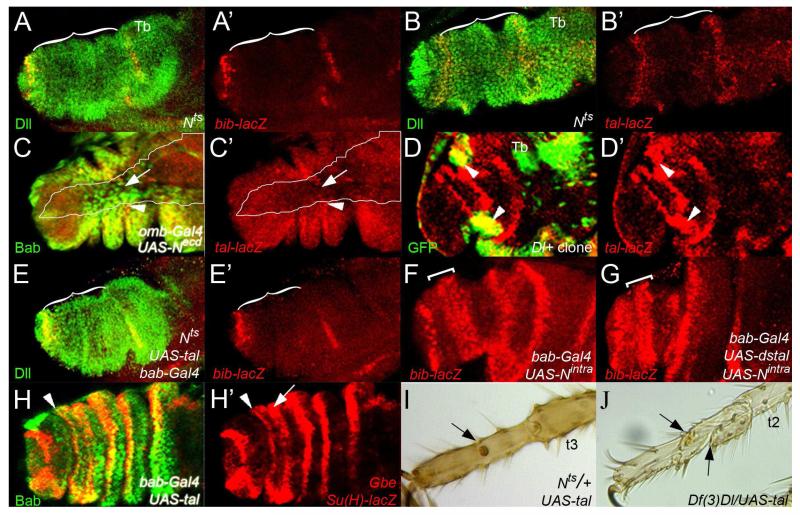

Figure 3. N signalling functions upstream and downstream of Tal in joint development.

A- A′- Distal part of a Nts mutant pupal leg (4h APF) shifted to the restrictive Ta at late third instar, showing the unaffected expression of the Dll gene (green), that is not regulated by N, and bib-lacZ (red). No bib-lacZ expression is detected in the tarsus (brackets). (A′) red channel.

B- B′- Nts mutant pupal leg (6h APF) treated as in A) showing tal-lacZ (red) and Dll (green) expression patterns (B). tal-lacZ expression is missing in the tarsus (brackets) (B′).

C- C - Ectopic expression of a dominant negative N form (Necd) using omb-Gal4 driver in a pupal leg (6h APF) showing tal-lacZ (red) and Bab (green). Note that only Bab is expressed in the dorsal part of the disc (arrow) and tal-lacZ expression is repressed from this domain and only detected in the lateral parts (arrowhead) outside of omb-Gal4 domain (outline) (C). tal-lacZ expression (C′).

D- D′- tal-lacZ (red) pupal leg (4h APF) containing Dl gain of function clones (green). Ectopic expression of tal-lacZ is observed in the Dl-expressing clones (arrowheads) (D). tal-lacZ expression (D′).

E- E′- Overexpression of tal in a Nts mutant background pupal leg (4h APF) showing Dll (green) and bib-lacZ (red) expression patterns (E). bib-lacZ expression is lost in the tarsal segments (brackets) (E′).

F- F′- Pupal leg (5h APF) expressing Nintra in the tarsal region. Nintra expands bib-lacZ expression in the tarsus (bracket).

G- Ectopic co-expression of Nintra and UAS-dstal in the tarsi of a pupal leg (5h APF). bib-lacZ still appears expanded in the tarsus (bracket).

H- H′- A 6h APF bab-Gal4;UAS-tal pupal leg showing the expression of an enhancer regulated directly by Nintra (Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ) (red) and Bab (green). Ectopic expression of Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ is observed in t4 in a row of cells (arrow) more proximal to the endogenous pattern (arrowhead); compare with Figs. 2D-E (H). Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ expression (H′).

I- Distal part of a bab-Gal4;UAS-tal leg in a Nts heterozygous background. No ectopic joint structures are detected. Instead some tarsus display defective joints (arrow).

J- Tarsi of a leg over-expressing tal in a heterozygous background for Dl (Df(3)DlBX12/+). As in I), no ectopic joint tissue is observed and some tarsal joints are defective, leading to tarsal segment fusions (arrows).

However, further genetic tests reveal a more complex scenario. Firstly, the ectopic joint phenotype produced by over-expression of UAS-driven Tal peptides in the tarsi is suppressed by N or Dl haplo-insufficiency (Fig. 3 I, J). Since tal expression in these experiments is regulated by the bab-Gal4 driver and thus does not depend on N, the observed phenotypic suppression must be due to a post-transcriptional interaction between Tal peptides and the N pathway. Secondly, UAS-driven expression of tal does not rescue the Nts mutant phenotype and does not restore bib-lacZ expression (Fig. 3E-E′;compare with A-A′), suggesting that Tal peptides are unable to induce joints in the absence of N. Finally, the phenotype caused by ectopic expression of the Nicd is epistatic over the loss of joint markers induced by ectopic expression of the UAS-dstal RNAi construct (Fig. 2C-C′; Fig. 3F, G). Thus, although N signalling is required for the activation of tal expression, these results suggest that N signalling also acts downstream of tal. One possible explanation is that Tal peptides interact with the product of a gene regulated by N in a feed-forward mechanism; however, it may be also possible that Tal function feeds back on the N pathway.

To test whether Tal function involves direct interaction with the N signalling pathway and not a downstream gene product, we have used reporters activated by direct binding of Nintra and Suppressor of Hairless (Su(H)) to their regulatory sequences. The grainyhead Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ reporter is expressed in the joint regions (Suppl. Fig. 2E;Furriols and Bray, 2001) and is activated ectopically by over-expression of tal in the tarsi (Fig. 3H-H′) in a similar manner to bib-lacZ (Fig. 2 D-D′). In addition, tal gain of function clones also induce ectopic E(spl)mβ-lacZ expression non-autonomously proximal to the endogenous tarsal joint expression (Suppl. Fig. 2C, F-F′;Cooper et al., 2000). Reciprocally, E(spl)mβ-lacZ expression is lost in tal mutant clones in a non-autonomous manner (Suppl. Fig. 2C, D-D′). Thus, these observations indicate that Tal peptides act upstream of the direct transcriptional targets of N and therefore directly on the N pathway itself.

Altogether these genetic interactions suggest that N signalling is acting at two different levels in relation to tal function. On the one hand, N signalling is upstream of the tal gene to activate its transcription. On the other hand, N signalling is essential for the joint promoting function of the Tal peptides. Thus, we surmise that Tal peptides act as feedback regulators of the N signalling pathway in the formation of tarsal joints.

3- Tal regulates N signalling by establishing a Dl+/Dl− boundary

To understand the mechanism by which Tal peptides signal back onto the N pathway, we compared the expression patterns of tal-lacZ to those of different components of the Notch pathway. The ligand Dl is expressed at low levels in the proximal and medial parts of the leg segments, with a stripe of high level of expression just proximal to distalmost region, where little or no Dl expression can be detected (Bishop et al. 1999). This pattern forms a sharp Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary that triggers N activation in the Dl-negative cells (Fig. 4A-A′′). tal-lacZ is expressed a few rows of cells further away from the Dl expressing domain (Fig. 4A-A′′); given the signalling function of Tal peptides, this suggests that a negative feedback loop between Tal and Dl may exist.

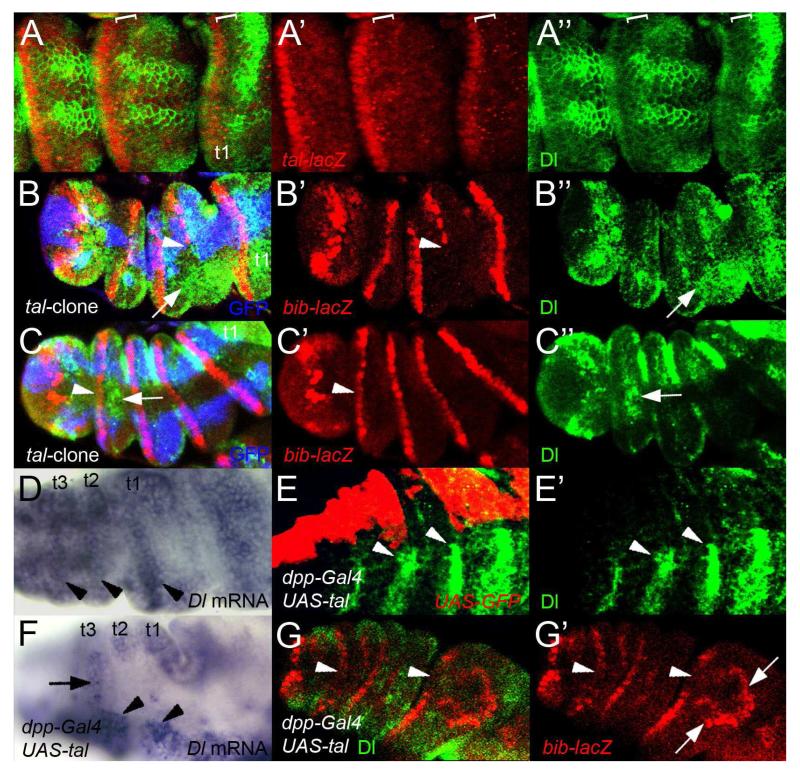

Figure 4. Tal represses Dl transcription in the N-responsive region to form a signalling border.

A- A′′- Patterns of expression of Dl (green) and tal-lacZ (red) in the distal part of a pupal leg (6h APF) Note that Dl and tal-lacZ patterns of expression do not overlap (brackets) (A). tal-lacZ expression in the distalmost part of the segment (A′). Dl distribution showing a sharp boundary with non-Dl-expressing cells at the distal part of the segment (brackets) (A′′).

B- B′′- 6h APF pupal leg showing a large Minute+ tal- mutant clone of around 10-15 cells wide (marked by lack of GFP, blue) and stained for bib-lacZ (red) and Dl expression (green) (B). bib-lacZ is lost in the larger area of the clone. Arrowhead denotes the edge of bib-lacZ expression. (B′) Dl distribution in this area does not form a boundary and it appears more distally (arrow) (B′′)

C- C′′- Average Minute + tal− mutant clone in a 6h APF pupal leg labelled as in B). bib-lacZ expression is normal in the tal mutant clone (arrowhead) (C′). Dl is localized proximally forming a clear boundary (arrow; compare with B′′) (C′′).

D- Dl mRNA distribution in a 5h APF pupal leg. Dl is highly expressed near the distal part of the segment (arrowheads), but is absent or at low concentration in the distalmost part.

E- E′- Pupal leg (6h APF) over-expressing UAS-tal and UAS-GFP driven by dpp-Gal4, showing the GFP distribution in the dpp pattern (red) and Dl protein (green) (E). Dl protein (green) is only detected outside of the tal over-expressing domain (arrowheads) (E′).

F- in situ hybridisation using a Dl riboprobe in a dpp-Gal4;UAS-tal pupal leg 5h APF. Dl transcription is repressed in tal over-expressing cells (arrow). Dl expression is detected outside the dpp pattern (arrowheads).

G- G′- Ectopic expression of tal in a 5h APF pupal leg with dpp-Gal4 driver represses Dl (green) and bib-lacZ (red) in the dorsal part of the disc (arrowheads) but induces ectopic expression domains of bib-lacZ at the edges of the dpp-Gal4 domain (arrows) (G). Expression of bib-lacZ (G′).

Several results support this hypothesis. First of all, in large tal loss of function clones in which bib-lacZ expression is lost, Dl expressing cells are ectopically found in the distalmost part of the segment (Fig. 4B-B′). However, Dl and bib-lacZ expression are not affected in smaller tal mutant clones, indicating that Tal represses Dl expression non-autonomously (Fig. 4C-C′′). Secondly, ectopic expression of tal with the dpp-Gal4 driver represses Dl expression (Fig. 4E-E′). This repression inhibits the formation of the joints in the dpp region which is corroborated by the loss of joint markers (Fig. 4G-G′). However, in some instances Tal-mediated repression of Dl also allows the creation of new Dl+/Dl− signalling boundaries that activate N signalling at the edges of the dpp expression domain and induce the expression of bib-lacZ proximally to the endogenous joint territory (Fig.4G-G′). Finally, this regulation of Dl is at the level of transcription as Dl mRNA is down-regulated in dpp-Gal;UAS-tal pupal legs (Fig.4 D, F). Thus the Tal peptides in the joint region repress Dl transcription, generating a signalling border which is essential for the activation of N downstream targets.

4- Tal-mediated activation of the transcription factor Svb represses Dl expression

tal is a non-canonical gene that encodes four small related peptides which behave genetically as cell signals but their mechanisms of action are still not well understood. Recently, Kondo and colleagues have demonstrated that Tal peptides trigger a functional switch in the Svb transcription factor during embryonic epidermal differentiation. In the absence of Tal, Svb protein acts a repressor of denticle formation, but in the presence of Tal, Svb protein is converted into an activator. We have explored whether the role of Tal in the transcriptional regulation of Dl is mediated by Svb. We observe that the svb mRNA is expressed in the presumptive joint regions in late third instar (not shown) and pupal legs (Fig. 5A). Similarly, a svbPL107 (svb-lacZ) enhancer trap, which reproduces the endogenous svb pattern during embryogenesis (Bourbon et al., 2002), is also expressed in stripes of cells mostly distal to the Dl expression domain in pupal legs (Fig. 5H-H′′). Crucially, expression of a Svb-GFP construct in the tarsus shows that Svb-GFP is localized throughout the nucleus in the distal part of the segments near bib-lacZ expression whereas it is localized in nuclear puncta structures in more proximal parts (Fig. 5G-G′′). This result suggests that, as has been observed in the embryo, Svb post-transcriptional activation takes place where Tal peptides are present. These results indicate that Svb may indeed be the effector of tal function for the transcriptional repression of Dl in the tarsi. Supporting this view, escapers of the svb hypomorphic allele, svbP107, show incomplete joint formation in some tarsal segments (Fig. 5B). To further explore this hypothesis we have performed mosaic analysis using a svbR9 null allele. Quantification of the number of svb mutant clones running through joints between true segments and between the tarsi shows that the number of svb clones crossing the tarsal joints is lower than expected (Suppl. Table 2). From these tarsal joint-crossing svbR9 clones, those being two or more rows of bristles wide (>25%) produced an autonomous loss of joint tissue (Fig. 5C) (Suppl. Table 2). Thus, we conclude that svb is expressed and required for tarsal joint development.

Figure 5. Tal regulates N signalling through the Svb transcription factor.

A- Distribution of svb mRNA in a 4h APF pupal leg. svb is detected in stripes in the tarsal segments.

B- Tarsal joints of a svb107 mutant escaper displaying an incomplete joint (arrowhead).

C- A svbR9 mutant clone marked with yellow in the tarsal segments (outlined in red). The cells lacking svb do not form autonomously the joint fold (arrowhead).

D- Leg of a fly over-expressing UAS-svb in the tarsi is completely wild-type.

E- Leg over-expressing both UAS-tal and UAS-svb using the bab-Gal4 driver. Apart from an abnormal joint in t1 (arrow) only attempts of joints can be observed in the rest of the tarsus (arrowhead).

F- Distal part of a leg over-expressing an active Svb form (ovo-B) in the tarsi. The tarsal region is reduced and all joints are completely absent.

G- G′′- Distribution of a GFP-tagged Svb protein (Svb-GFP) (red) in a tarsal segment of a pupal leg using the bab-Gal4 driver, which is expressed evenly throughout the tarsus. Expression of the bib-lacZ (green) indicates the proximal part of the joint region. (G). Svb-GFP is differentially distributed throughout the segment. In the joint region (thin brackets) Svb-GFP is strongly detected in entire nuclei (arrows) whereas in the proximal (non-joint) part of the segment (thick brackets), Svb-GFP is only detected in puncta (arrowheads) (G′). bib-lacZ expression (G′′).

H- H′′- A 5h APF pupal leg showing svb-lacZ (red; arrowhead) and Dl (green; arrow) patterns of expression. Note that these adjacent expression domains are slightly overlapping (H). svb-lacZ reporter is expressed in the distal part of the tarsal segments (arrowheads) (H′). Dl protein distribution (arrow) (H′′).

I- A bab-Gal4;UAS-tal;UAS-svb pupal leg (5h APF) showing a strong reduction of bib-lacZ expression in the tarsi (brackets).

J- A pupal leg (5h APF) over-expressing ovo-B in the tarsi. The bib-lacZ pattern of expression is completely lost or very reduced (brackets).

K- in situ hybridisation showing the Dl transcript pattern in a dpp-Gal4;UAS-ovoB pupal leg (4h APF). Dl expression is reduced in the dorsal part of the disc (arrow) but stripes of Dl are observed outside the dpp-Gal4 domain (arrowheads).

L- L′′- A 5h APF pupal leg expressing ectopically ovo-B using the dpp-Gal4 driver (white outline) showing Dl protein distribution (green) and bib-lacZ expression (red). Arrow denotes the dorsal side of the disc where Dl is reduced and bib-lacZ expression is absent; the arrowhead marks the lateral side where bib-lacZ and Dl are present (L). Dl protein expression (L′). bib-lacZ expression (L′′).

We have undertaken ectopic expression experiments to demonstrate that Dl repression induced by Tal peptides in the tarsal joint is mediated by Svb activation. Ectopic expression of svb using the bab-Gal4 driver does not produce phenotypes in the leg (Fig. 5D) which suggest that the encoded Svb protein requires post-transcriptional activation. However, ectopic co-expression of svb with tal produces loss of joints in the tarsi (Fig. 5E) and a significant reduction of bib-lacZ expression in pupal legs (Fig. 5I). This result might seem contradictory with the previous finding of a joint-promoting function for tal, and in particular, with ectopic joints in bab-Gal4;UAS-tal legs (Fig. 1F; 2D-D′). A possible interpretation is that Tal and Svb are actually repressing N signalling. Corroborating this hypothesis, ectopic expression of a Svb constitutively active form (OvoB) with bab-Gal4 driver produces shorter tarsi lacking all joints (Fig. 5F), in which bib-lacZ expression is highly reduced or absent in pupal legs (Fig. 5J). Similarly, reduction of bib-lacZ expression and Dl protein distribution is observed in dpp-Gal4;UAS-tal;UAS-svb (not shown) and dpp-Gal4;UAS-ovoB (Fig. 5L-L′′) pupal legs leading to loss of joint tissue (Suppl. Fig. 3D, E). Finally, this repression of Dl expression is at the level of transcription as Dl mRNA is downregulated in dpp-Gal4;UAS-ovoB pupal legs (Fig. 5K). Therefore, Tal-mediated activation of Svb promotes the repression of Dl in the tarsal joint region.

Thus, Tal peptides appear to promote N signalling by generating a sharp signalling boundary through the transcriptional repression of Dl in the presumptive joint region. This repression is mediated by the activation of the Svb transcription factor and allows directional N signalling activation and the formation of the tarsal joints (Fig. 6). Hence in our model, for Tal and Svb to promote joint formation, Tal and Svb must overlap and either overlap or abut high Dl expression. This model explains our experimental data in which perturbations of svb and tal functions disrupt N signalling and joint formation. Complete depletion of tal or svb function in the tarsal joints (as in tal or svb loss of function clones or by ectopic expression of UAS-dstal construct; Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5) results in the expansion of Dl into the joint region and precludes the formation of Dl+/Dl− sharp boundaries, leading to a loss of tarsal joints. Ectopic expression of activated Svb (by means of ovo-B expression or tal and svb co-expression; Fig. 5) represses Dl and hence also eliminates Dl+/Dl− signalling boundaries and joint structures. Finally, when UAS-tal is ectopically expressed in the tarsi, ectopic joints only arise in the region where endogenous Svb is present but out of reach of the endogenous Tal source, and yet overlapping the stripe of high Dl: these three conditions are only met in a narrow stripe proximal to the endogenous presumptive joint (Fig. 6). Consequently, repression of Dl is achieved in this region and new Dl+/Dl− boundaries and ectopic joints form proximally to the endogenous joint region (Figs. 1J, 2D-E and 4G).

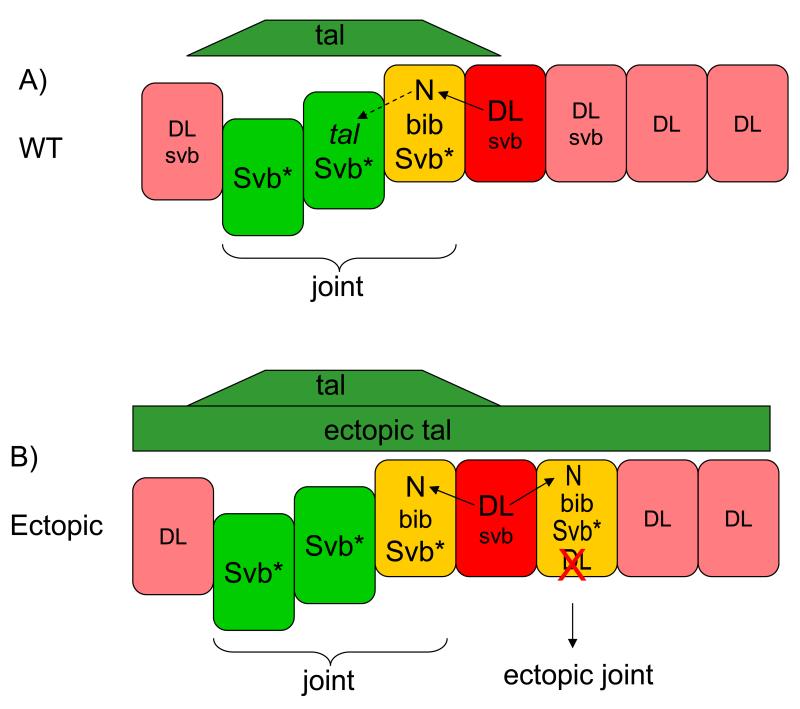

Figure 6. Diagram depicting a model for the interactions between Tal and N during tarsal joint development.

Schematic representation of the Tal-mediated mechanism controlling the formation of the N signalling boundary in the distal part of a tarsal segment in pupal legs (the orientation of the represented tarsal segments is as in other figure panels, distal to the left and proximal to the right). A negative feedback between N and Tal signalling regulates the formation and maintenance of N-signalling boundary. Joints (endogenous or ectopic) only arise if a) both tal and svb expression overlap (green) and b) this tal-svb overlap in turn abuts or overlaps high Dl expression (red; overlaps in yellow). These overlaps leads to the generation of a sharp Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary. A) By the end of third larval instar, Dl (red) and svb are expressed in slightly overlapping patterns in the distal part of the segment. At the onset of puparation, cells high levels of Dl and activate N signalling in the adjacent cells (black arrow). N signalling activates (directly or indirectly) tal gene expression in the distalmost part of the joint region (black dashed arrow). Non-autonomous Tal signalling (green) triggers the post-transcriptional activation the Svb transcription factor (Svb*) across the presumptive joint region (bracket). Subsequently, this Tal-mediated activation of Svb results in the direct or indirect transcriptional repression of Dl in the presumptive joint cells (yellow), generating a sharp Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary that leads to the activation of bib and other joint-promoting genes. Loss of tal or svb function results in the loss of this boundary, and hence, of joints. B) UAS-tal-mediated ectopic joints only arise in the region where endogenous Svb is present but out of reach of the endogenous Tal source, and yet overlapping or abutting the distal stripe of high Dl: these three conditions are only met in a narrow stripe proximal to the endogenous presumptive joint. Activation of Svb in this territory represses Dl and leads to the generation of a new Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary and the formation of an extra joint (arrows). Co-over-expression of UAS-svb plus UAS-tal, or expression of the Svb-activated form ovo-B throughout the segment eliminates Dl expression and precludes the formation of Dl+/Dl− signalling borders and joints.

Discussion

A distinct role for non-canonical Tal peptides in the generation of patterning and signalling boundaries that allow the specification of new territories of cells in a growing tissue is starting to emerge. The molecular mechanisms employed by Tal peptides seem to vary depending on the developmental context. During development of the tarsal joints, the N signalling pathway activates tal expression in each presumptive joint region. Subsequently, Tal peptides activate the transcription factor Svb, which represses Dl expression to define a sharp Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary. Thus, a negative feedback loop between Tal and the N pathway produces a spatial asymmetry in the distribution of the ligand Dl, which is essential for the directional activation of N signalling in the joint region. Importantly, Tal peptides act non-autonomously maintaining this border allowing the recruitment of cells into the presumptive joint region as the expression of Dl retracts out of range from the Tal domain of action. During tarsal intercalation at mid-third instar, tal expression is activated at the border of the B and dac expression domains (Pueyo and Couso, 2008). Next, tal is involved in a negative feedback loop, by which Tal peptides activate the expression of the transcription factors, Rn and Ss, that in turn repress B and dac expression and promote tarsal development (Pueyo and Couso, 2008). Again, the non-autonomous nature of Tal signalling allows the expansion of the new intercalated territory from a single row of cells to a territory comprising three tarsal segments (Pueyo and Couso, 2008). Interestingly, several pieces of evidence suggest that tal function in tarsal intercalation is independent of Svb. Firstly, svb is not expressed in the presumptive tarsus in mid third instar leg discs (not shown). Secondly, svb loss of function precludes the development of tarsal joints but not of tarsal segments themselves (see below). Thus, Tal peptides are involved in distinct negative feedback loops in the formation of patterning and signalling boundaries.

1- Regulation of N signalling during tarsal joint development

By late third larval instar, the different presumptive tarsal segment regions have been specified by the gene regulatory network of PD genes, including tal (Campbell, 2005; De Celis Ibeas and Bray, 2003; Galindo and Couso, 2000; Kojima et al., 2000; Pueyo and Couso, 2008; Pueyo et al., 2000). A concentric ring of Dl-expressing cells appear in the distal part of each tarsal segment (Bishop et al., 1999; de Celis et al., 1998; Rauskolb and Irvine, 1999). In addition, other factors such as Fringe, the Ras and PCP pathways and the Dve transcription factor counteract N activity in the cells proximal to the Ser/Dl rings of expression and restrict the ability to respond to N signalling to the cells distal to the Ser/Dl expression domains ((Bishop et al., 1999; Ciechanska et al., 2007; de Celis et al., 1998; Galindo et al., 2005; Shirai et al., 2007). However, a sharp Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary must be generated for downstream gene activation and joint determination to occur. The AP-2 transcription factor and other unknown factors are involved in repressing Ser and Dl in the tarsal joint region (Ciechanska et al., 2007). During puparium formation, this signalling boundary must be maintained as the leg expands and undergoes morphogenetic changes (Fristrom and Fristrom, 1993; Greenberg and Hatini, 2010; Mirth and Akam, 2002). tal expression is precisely activated by N signalling in the presumptive joint region at the onset of puparation (Figs. 1 and 3). Although it is not known whether N mediated activation of tal expression is direct or indirect, we have found two putative Su(H) binding sites (Bailey and Posakony, 1995), one at 0.6Kb upstream of the start of tal transcription, and the other at 1.5Kb downstream of the tal transcript, suggesting that the regulation of tal by N could be direct (unpubl. obs.). Clonal analysis and ectopic expression studies show that tal is required for joint development (Figs.1 and 2), and that tal is involved in a negative feedback loop with N signalling by which Tal peptides repress Dl expression in the joint region (Fig. 4). This repression is implemented by Svb, either directly acting as a transcriptional repressor on the Dl gene, or indirectly by activating another repressor, such as the AP-2 gene. Therefore, Tal is a factor that maintains the Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary in tarsal joints.

Denticle formation in embryogenesis relies on Tal triggering a post-translational modification of the Svb transcription factor (Kondo et al., 2010). Upon this modification Svb switches from a repressor, which is localized in nuclear foci, to an activator, which is evenly distributed in the nucleus (Kondo et al., 2010). Similarly, svb is expressed in the joint region in every segment from third larval instar and our results indicate that svb is required for tarsal joint formation (Fig. 5). Our functional analyses suggest that Tal-mediated activation of Svb regulates the N signalling border in the tarsal segments in correlation with Svb-GFP being evenly distributed in the nuclei of the distalmost cells of each segment where tal is functional. However, there exist some differences between the role of Svb in denticles and in tarsal joints. For instance, ectopic expression of Svb does not affect tarsal segmentation. This supports the view that endogenous tal expression controls the activation of Svb only in the joint region, and Svb does not play a role in joint formation in the absence of Tal.

These findings together with the similarities found in the tal and svb mutant phenotypes in other developmental contexts (Delon et al., 2003; and unpubl. obs.) suggest that most, if not all, of the Svb functions, in which Svb post-transcriptional activation is required, maybe regulated by Tal peptides. Conversely, there exist roles of Tal that are independent of Svb, such as in the trachea and tarsal intercalation (Kondo et al., 2010; Pueyo and Couso, 2008), indicating that Tal peptides have an alternative and yet unknown mode of action.

Two distinct negative feedback mechanisms are involved in the segmentation of the Drosophila leg. In the true joints, a negative feedback cascade involving the regulation of the degradation of Bowl and N signalling permits the formation and maintenance of the Dl+/Dl− signalling boundary (Greenberg and Hatini, 2009). In the tarsal joints, activation of tal expression by N signalling in the joint region promotes Svb activation and repression of Dl. However, there exist other regulators, such as AP-2 and other odd-related genes (sister of odd and bowl (sob) and odd) that may also be involved in either of these two mechanisms refining the Dl+/Dl− signalling boundaries (Ciechanska et al., 2007; Greenberg and Hatini, 2009; Hao et al., 2003).

2-Conservation of a tal-Svb-Notch regulatory pathway

The available comparative evidence suggests that Tal regulation of N signalling is ancestral for arthropods. Expression and functional analyses of N, Ser and Dl have shown that N is involved in the segmentation of legs of spiders (Prpic and Damen, 2009) and basal insects such as the cockroach Periplaneta americana (Turchyn et al., 2011). In addition, the N target genes such as AP-2, and odd-related genes are also expressed in all the segments in spiders indicating conservation in the segmentation mechanisms across arthropods (Prpic and Damen, 2009). In the beetle Tribolium castaneum, the tal homologue, mille-pates(mlpt), is expressed in three stripes in the developing leg, one in each of the three larval leg segment, all of which will give rise to true joints (Savard et al., 2006). mlpt RNAi embryos seem to display slightly shorter and deformed legs, possibly as a result of fusion of leg segments (Savard et al., 2006). Furthermore, stripes of tal expression can be observed near the leg joints in Periplaneta and in the cricket Grillus bimaculatus (Chesebro and Couso, 2009). Although further work into the role of tal and odd-related genes in leg segmentation in basal insects and other arthropods is needed, these comparative data support the hypothesis that both the Odd-related gene cassette and Tal signalling regulate the formation of N signalling boundaries in the leg joints in most basal arthropods. In more derived insects, such as Drosophila the Odd-related gene cassette and Tal mechanisms may have specialized into the formation of joints of either true or tarsal segments respectively.

The tal expression observed in leg joints in Coleoptera (Tribolium), Orthoptera (Gryllus) and Dyctioptera (Periplaneta) suggests that tal joint function and its relationship with svb predates the association of tal and svb in the development of denticle patterns in Dipterans, which must have been co-opted a posteriori. This conclusion would also push the functional link between tal and svb in regulating N signalling back almost 400myr. However, this functional connection may extend back even further in time. The vertebrate Svb homologues MOVO1 and 2 share some functional similarities with their Drosophila counterpart. They are expressed in epidermal hair cells and in reproductive systems and their knockout mutants fail to form these structures properly (Dai et al., 1998; Li et al., 2002a; Li et al., 2002b). In addition, N signalling has two distinct roles during epidermal hair development, an early role acting as a switch between different epidermal cell lineages and a later one in the terminal differentiation of the hair cells (Blanpain et al., 2006; Pan et al., 2004; Vauclair et al., 2005). Interestingly, the MOVO2 transcription factor regulates terminal differentiation of keratinocytes by repressing directly the expression of the Notch 1 receptor (Wells et al., 2009). These findings reveal a functionally analogous feedback loop involving Svb/Ovo and N in Drosophila and vertebrates. Finding the tal homologue in vertebrates and exploring its role in hair development and N regulation would therefore seem a worthwhile quest. Reducing N signalling using small molecules has been shown as a promising avenue of research for treating diseases where mis-regulation of N is involved, such as in leukaemias and breast cancer (Moellering et al., 2009; Rizzo et al., 2008; Weng et al., 2004). Testing a putative role for small peptides in regulating N signalling in human cells could also open new therapeutic avenues for these diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Expression of a dstal construct knocks down tal function and mimics N loss of function phenotypes in joints.

A- A′′- bab-Gal4 expression (green) in a pupal leg (3h APF) mimics Bab protein (red) distribution (A). Bab protein (A′). Expression of the bab-Gal4 driver revealed by UAS-GFP (A′′).

B- Distal part of the leg of a thermosensitive Nts mutant shifted to restrictive temperature at third instar larvae. Tarsal joints do not develop (arrowhead).

C- Tarsi of a fly expressing a tal double stranded RNAi fragment in the Dll-Gal4 expression pattern. Tarsal segments are fused as no joint structures are formed (arrowheads).

D- Wild-type pupal leg (4h APF) showing stripes of tal mRNA expression in the tarsus (arrows).

E- tal mRNA pattern is lost in the tarsi (brackets) in a bab-Gal4;UAS-dstal pupal leg (4h APF).

F- Expression of the Tal1A peptide (Galindo, Pueyo et al. 2007) tagged with GFP using the act5-Gal4 driver in S2R+cells. Note that Tal1A-GFP is strongly expressed in transfected cells.

G- Co-transfection of the Tal1A-GFP and the UAS-dstal constructs in S2R+cells. Note that Tal1A-GFP expression is strongly reduced.

Supplementary Figure 2. Ectopic expression of tal induces ectopic joints without affecting the proximodistal patterning.

A- A′′- Expression of the AP-2 joint marker (red) in the presumptive tarsal joints (arrowheads) in a 5h APF pupal leg in which the tarsi are labelled with Bab (green) (A) . Expression of AP-2 in joint region (arrowheads) (A′). Bab protein distribution (A′′).

B- B′′- A bab-Gal4;UAS-tal pupal leg (5h APF) labelled as in B. An ectopic stripe of AP-2 expression (arrow) is detected proximally to the endogenous one (arrowhead) (B). AP-2 is expressed in two rows of cells (B′). Bab expression (B′′).

C- Expression of E(spl)mβ-lacZ is in the distal, N-responsive region of the tarsal segments.

D- D′- Distal part of an E(spl)mβ-lacZ pupal leg (6h APF) containing Minute+tal mutant clones induced at 96-120h AEL. GFP (green) expression denotes tal heterozygous cells. Expression of E(spl)mβ-lacZ (red) is loss in large tal mutant clones (arrowheads) (D). E(spl)mβ-lacZ expression (D′).

E- A 6h APF pupal leg expressing the N responsive reporter Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ (red). Note that a Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ stripe is observed in the distal part of each tarsal segment in the presumptive joint region (arrow).

F- F′- Detail of the pupal leg showing that tal gain of function clones (green) activate ectopic E(slp)mβ-lacZ (red) expression non-autonomously (arrowhead) (F). Ectopic E(spl)mβ-lacZ expression (arrowhead) is detected just proximal to the endogenous stripe (arrow) (F′).

G- G′′- Distribution of the proximodistal patterning genes, B (red) and dac (green) in a 4h APF pupal leg (G). Dac is detected strongly in the first and faintly in the second tarsal segments (G′). B expression is confined to the fifth and four tarsal segments (G′′). The gap between B and Dac expression domains is shown (brackets); see also (Pueyo and Couso 2008).

H- H′′-, A bab-Gal4;UAS-tal pupal leg (4h APF) labelled as in G. Ectopic tal expression in the tarsi does not affect Dac and B patterns of expression (H). Dac pattern of expression reaches faintly the second tarsal segment (H). B expression is observed to the fifth and four tarsal segments (H′′).

I- I′′-A 4h APF pupal leg over-expressing ovo-B in the tarsi labelled as above. Miss-expression of ovo-B does not disrupt Dac and B patterns of expression (I). Dac expression (I′). B expression (I′′).

Supplementary Figure 3. N signalling regulates tal expression during puparation and activated svb over-expression inhibits joint formation.

A- A′- Ectopic expression of Dl using the ptc-Gal4 driver in a 6h APF pupal leg denoting tal-lacZ (red) and the ptc patterns of expression (green) (A). Ectopic expression of tal-lacZ in the ptc pattern (arrowhead); arrow points the endogenous tal-lacZ expression in the distal part of the segment (A′).

B- B′- A mid third instar ptc-Gal4;UAS-Nintra leg disc expressing tal-lacZ reporter showing Gal4 domain (green) and tal-lacZ (red). Ectopic activation of N signalling does not affect the tarsal tal-lacZ pattern of expression (arrow) (B). Expression of tal-lacZ (B′).

C- C′- Ectopic expression of Dl using the ptc-Gal4 driver in a mid third instar leg disc showing tal-lacZ (red) and ptc-Gal4 (green) patterns of expression. Expression of tal-lacZ is normal (arrow) (C). tal-lacZ expression (C′).

D- Ectopic expression of both svb and tal using dpp-Gal4 driver produces legs with fused segments lacking joints dorsally. The arrowheads mark the apical bristles of tarsal segments

E- Dpp-Gal4 driven expression of a constitutive active form of Svb, ovo-B, abolishes the formation of joints. Apical bristles at the end of the tarsal segments are labelled by arrowheads.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank D. Stern for sharing unpublished data; F. Payre, P. Mitchell, T. Klein, the Bloomington Stock center, the Drosophila Genomics Resourse Center and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for fly stocks, reagents and antibodies; and R. Ray and C. Alonso for their helpful comments on the manuscript. Finally, we also thank other members of the lab for their help and support. This work has been supported by a Senior Wellcome Trust fellowship awarded to JPC, ref. 087516.

References

- Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–6. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AM, Posakony JW. Suppressor of hairless directly activates transcription of enhancer of split complex genes in response to Notch receptor activity. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2609–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becam I, Fiuza UM, Arias AM, Milan M. A role of receptor Notch in ligand cis-inhibition in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2010;20:554–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SA, Klein T, Arias AM, Couso JP. Composite signalling from Serrate and Delta establishes leg segments in Drosophila through Notch. Development. 1999;126:2993–3003. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.13.2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Canonical notch signaling functions as a commitment switch in the epidermal lineage. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3022–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.1477606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbon H-M, Gonzy-Treboul G, Peronnet F, Alin M-F, Ardourel C, Benassayag C, Cribbs D, Deutsch J, Ferrer P, Haenlin M, Lepesant J-A, Noselli S, Vincent A. A P-insertion screen identifying novel X-linked essential genes in Drosophila. Mechanisms of Development. 2002;110:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxshall GA. The evolution of arthropod limbs. Biological Reviews. 2004;79:253–300. doi: 10.1017/s1464793103006274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusca RC, Brusca GJ. Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera GR, Godt D, Fang PY, Couderc JL, Laski FA. Expression Pattern of Gal4 Enhancer Trap Insertions Into the bric a brac LOcus Genereated by P Element Replacement. Genesis. 2002;34:62–65. doi: 10.1002/gene.10115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleja M, Moreno E, Pelaz S, Morata G. Visualization of gene expression in living adult Drosophila. Science. 1996;274:252–255. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G. Regulation of gene expression in the distal region of the Drosophila leg by the Hox11 homolog, C15. Developmental Biology. 2005;278:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesebro J, Couso JP. Expression and function of tarsal-less and segmentation genes in the American cockroach, Periplaneta americana. Mech Dev. 2009;126:S314. [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanska E, Dansereau DA, Svendsen PC, Heslip TR, Brook WJ. dAP-2 and defective proventriculus regulate Serrate and Delta expression in the tarsus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genome. 2007;50:693–705. doi: 10.1139/g07-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MT, Tyler DM, Furriols M, Chalkiadaki A, Delidakis C, Bray S. Spatially restricted factors cooperate with notch in the regulation of Enhancer of split genes. Dev Biol. 2000;221:390–403. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Schonbaum C, Degenstein L, Bai W, Mahowald A, Fuchs E. The ovo gene required for cuticle formation and oogenesis in flies is involved in hair formation and spermatogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3452–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Celis Ibeas JM, Bray SJ. Bowl is required downstream of Notch for elaboration of distal limb patterning. Development. 2003;130:5943–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.00833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis JF, Tyler DM, de Celis J, Bray SJ. Notch signalling mediates segmentation of the Drosophila leg. Development. 1998;125:4617–4626. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delon I, Chanut-Delalande H, Payre F. The Ovo/Shavenbaby transcription factor specifies actin remodelling during epidermal differentiation in Drosophila. Mechanisms of Development. 2003;120:747–758. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming RJ, Purcell K, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The NOTCH receptor and its ligands. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:437–441. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini ME. Notch signaling: the core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 2009;16:633–47. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristrom DK, Fristrom JW. The metamorphic development of the adult epidermis. In: Bate M, Arias A. Martinez, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Vol. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1993. pp. 843–897. [Google Scholar]

- Furriols M, Bray S. A model Notch response element detects Suppressor of Hairless-dependent molecular switch. Curr Biol. 2001;11:60–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo MI, Bishop SA, Couso JP. Dynamic EGFR-Ras signalling in Drosophila leg development. Developmental Dynamics. 2005;233:1496–1508. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo MI, Couso JP. Intercalation of cell fates during tarsal development in Drosophila. BioEssays. 2000;22:777–780. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9<777::AID-BIES1>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo MI, Pueyo JI, Fouix S, Bishop SA, Couso JP. Peptides encoded by short ORFs control development and define a new eukaryotic gene family. Plos Biology. 2007;5:e106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L, Hatini V. Essential roles for lines in mediating leg and antennal proximodistal patterning and generating a stable Notch signaling interface at segment borders. Developmental Biology. 2009;330:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg L, Hatini V. Systematic expression and loss-of-function analysis defines spatially restricted requirements for DrosophilaRhoGEFs and RhoGAPs in leg morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi D, Engel M. Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hao I, Green RB, Dunaevsky O, Lengyel JA, Rauskolb C. The odd-skipped family of zinc finger genes promotes Drosophila leg segmentation. Dev Biol. 2003;263:282–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatini V, Green RB, Lengyel JA, Bray SJ, DiNardo S. The drumstick/lines/bowl regulatory pathway links antagonistic Hedgehog and Wingless signaling inputs to epidermal cell differentiation. Genes and Development. 2005;19:709–718. doi: 10.1101/gad.1268005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzler P, Bourouis M, Ruel L, Carteret C, Simpson P. Genes of the Enhancer of split and achaete-scute complexes are required for a regulatory loop between Notch and Delta during lateral signalling in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:161–71. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert SS, Jacobsen TL, Muskavitch MA. Feedback regulation is central to Delta-Notch signalling required for Drosophila wing vein morphogenesis. Development. 1997;124:3283–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.17.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber B, Monge I, Mueller M, Mitchell PJ, Cohen SM. The AP-2 transcription factor is required for joint formation and cell survival in Drosophila leg development. Development. 2001;128:1231–1238. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima T. The mechanism of Drosophila leg development along the proximodistal axis. Dev. Growth Differ. 2004;46:115–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima T, Sato M, Saigo K. Formation and specification of distal leg segments in Drosophila by dual Bar homeobox genes, BarH1 and BarH2. Development. 2000;127:769–778. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Hashimoto Y, Kato K, Inagaki S, Hayashi S, Kageyama Y. Small peptide regulators of actin-based cell morphogenesis encoded by a polycistronic mRNA. Nature Cell Biology. 2007;9:660–U87. doi: 10.1038/ncb1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Inagaki S, Yasuda K, Kageyama Y. Rapid construction of Drosophila RNAi transgenes using pRISE, a P-element-mediated transformation vector exploiting an in vitro recombination system. Genes Genet Syst. 2006;81:129–34. doi: 10.1266/ggs.81.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Plaza S, Zanet J, Benrabah E, Valenti P, Hashimoto Y, Kobayashi S, Payre F, Kageyama Y. Small peptides switch the transcriptional activity of Shavenbaby during Drosophila embryogenesis. Science. 2010;329:336–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1188158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecourtois M, Schweisguth F. The neurogenic suppressor of hairless DNA-binding protein mediates the transcriptional activation of the enhancer of split complex genes triggered by Notch signaling. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2598–608. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dai Q, Li L, Nair M, Mackay DR, Dai X. Ovol2, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila ovo: gene structure, chromosomal mapping, and aberrant expression in blind-sterile mice. Genomics. 2002a;80:319–25. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Mackay DR, Dai Q, Li TW, Nair M, Fallahi M, Schonbaum CP, Fantes J, Mahowald AP, Waterman ML, Fuchs E, Dai X. The LEF1/beta -catenin complex activates movo1, a mouse homolog of Drosophila ovo required for epidermal appendage differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002b;99:6064–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092137099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjon C, Sanchez-Herrero E, Suzanne M. Sharp boundaries of Dpp signalling trigger local cell death required for Drosophila leg morphogenesis. Nature Cell Biology. 2007;9:57–U66. doi: 10.1038/ncb1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AC, Lyons EL, Herman TG. cis-Inhibition of Notch by endogenous Delta biases the outcome of lateral inhibition. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1378–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirth C, Akam M. Joint development in the Drosophila leg: cell movements and cell populations. Dev Biol. 2002;246:391–406. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Kung AL, Gilliland DG, Verdine GL, Bradner JE. Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex. Nature. 2009;462:182–U57. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Lin MH, Tian X, Cheng HT, Gridley T, Shen J, Kopan R. gamma-secretase functions through Notch signaling to maintain skin appendages but is not required for their patterning or initial morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;7:731–43. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payre F. Genetic control of epidermis differentiation in Drosophila. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2004;48:207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prpic NM, Damen WG. Notch-mediated segmentation of the appendages is a molecular phylotypic trait of the arthropods. Dev Biol. 2009;326:262–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo JI, Couso JP. The 11-aminoacid long Tarsal-less peptides trigger a cell signal in Drosophila leg development. Developmental Biology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.025. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo JI, Galindo MI, Bishop SA, Couso JP. Proximal-distal leg development in Drosophila requires the apterous gene and the Lim1 homologue dlim1. Development. 2000;127:5391–5402. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C. The establishment of segmentation in the Drosophila leg. Development. 2001;128:4511–4521. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.22.4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Notch-mediated segmentation and growth control of the Drosophila leg. Developmental Biology. 1999;210:339–350. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo P, Osipo C, Foreman K, Golde T, Osborne B, Miele L. Rational targeting of Notch signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:5124–31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M, Pear WS, Aster JC. The multifaceted role of Notch in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savard J, Marques-Souza H, Aranda M, Tautz D. A segmentation gene in Tribollium produces a polycistronic mRNA that codes for multiple conserved peptides. Cell. 2006;126:559–569. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai T, Yorimitsu T, Kiritooshi N, Matsuzaki F, Nakagoshi H. Notch signaling relieves the joint-suppressive activity of Defective proventriculus in the Drosophila leg. Dev Biol. 2007;312:147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass RE. Principles of insect morphology. Cornell University Press; New York: 1993. p. 667. [Google Scholar]

- St Pierre SE, Galindo MI, Couso JP, Thor S. Control of Drosophila imaginal disc development by rotund and roughened eye: differentialy expressed transcripts of the same gene encoding functionally distinct zinc finger proteins. Development. 2002;129:1273–1281. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.5.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou S, Clarke RB, Brennan K. Aberrant activation of notch signaling in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1517–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajiri R, Misaki K, Yonemura S, Hayashi S. Dynamic shape changes of ECM-producing cells drive morphogenesis of ball-and-socket joints in the fly leg. Development. 2010;137:2055–63. doi: 10.1242/dev.047175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchyn N, Couso JP, Hrycaj S, Chesebro J, Popadic A. Embryonic functions of nubbin in hemimetabolous insects. Dev. Biol. 2011;357:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauclair S, Nicolas M, Barrandon Y, Radtke F. Notch1 is essential for postnatal hair follicle development and homeostasis. Dev Biol. 2005;284:184–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J, Lee B, Cai AQ, Karapetyan A, Lee WJ, Rugg E, Sinha S, Nie Q, Dai X. Ovol2 suppresses cell cycling and terminal differentiation of keratinocytes by directly repressing c-Myc and Notch1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29125–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris J. P. t., Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Blacklow SC, Look AT, Aster JC. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Expression of a dstal construct knocks down tal function and mimics N loss of function phenotypes in joints.

A- A′′- bab-Gal4 expression (green) in a pupal leg (3h APF) mimics Bab protein (red) distribution (A). Bab protein (A′). Expression of the bab-Gal4 driver revealed by UAS-GFP (A′′).

B- Distal part of the leg of a thermosensitive Nts mutant shifted to restrictive temperature at third instar larvae. Tarsal joints do not develop (arrowhead).

C- Tarsi of a fly expressing a tal double stranded RNAi fragment in the Dll-Gal4 expression pattern. Tarsal segments are fused as no joint structures are formed (arrowheads).

D- Wild-type pupal leg (4h APF) showing stripes of tal mRNA expression in the tarsus (arrows).

E- tal mRNA pattern is lost in the tarsi (brackets) in a bab-Gal4;UAS-dstal pupal leg (4h APF).

F- Expression of the Tal1A peptide (Galindo, Pueyo et al. 2007) tagged with GFP using the act5-Gal4 driver in S2R+cells. Note that Tal1A-GFP is strongly expressed in transfected cells.

G- Co-transfection of the Tal1A-GFP and the UAS-dstal constructs in S2R+cells. Note that Tal1A-GFP expression is strongly reduced.

Supplementary Figure 2. Ectopic expression of tal induces ectopic joints without affecting the proximodistal patterning.

A- A′′- Expression of the AP-2 joint marker (red) in the presumptive tarsal joints (arrowheads) in a 5h APF pupal leg in which the tarsi are labelled with Bab (green) (A) . Expression of AP-2 in joint region (arrowheads) (A′). Bab protein distribution (A′′).

B- B′′- A bab-Gal4;UAS-tal pupal leg (5h APF) labelled as in B. An ectopic stripe of AP-2 expression (arrow) is detected proximally to the endogenous one (arrowhead) (B). AP-2 is expressed in two rows of cells (B′). Bab expression (B′′).

C- Expression of E(spl)mβ-lacZ is in the distal, N-responsive region of the tarsal segments.

D- D′- Distal part of an E(spl)mβ-lacZ pupal leg (6h APF) containing Minute+tal mutant clones induced at 96-120h AEL. GFP (green) expression denotes tal heterozygous cells. Expression of E(spl)mβ-lacZ (red) is loss in large tal mutant clones (arrowheads) (D). E(spl)mβ-lacZ expression (D′).

E- A 6h APF pupal leg expressing the N responsive reporter Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ (red). Note that a Gbe+Su(H)-lacZ stripe is observed in the distal part of each tarsal segment in the presumptive joint region (arrow).

F- F′- Detail of the pupal leg showing that tal gain of function clones (green) activate ectopic E(slp)mβ-lacZ (red) expression non-autonomously (arrowhead) (F). Ectopic E(spl)mβ-lacZ expression (arrowhead) is detected just proximal to the endogenous stripe (arrow) (F′).

G- G′′- Distribution of the proximodistal patterning genes, B (red) and dac (green) in a 4h APF pupal leg (G). Dac is detected strongly in the first and faintly in the second tarsal segments (G′). B expression is confined to the fifth and four tarsal segments (G′′). The gap between B and Dac expression domains is shown (brackets); see also (Pueyo and Couso 2008).