Abstract

Purpose

Preclinical models suggest that the use of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) therapy with antiestrogens may prevent or delay the development of endocrine therapy resistance. We therefore performed a feasibility study to evaluate the safety of letrozole plus bevacizumab in patients with hormone receptor–positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC).

Methods

Patients with locally advanced breast cancer or MBC were treated with the aromatase inhibitor (AI) letrozole (2.5 mg orally daily) and the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab (15 mg/kg intravenously every 3 weeks). The primary end point was safety, defined by grade 4 toxicity using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0. Secondary end points included response rate, clinical benefit rate, and progression-free survival (PFS). Prior nonsteroidal AIs (NSAIs) were permitted in the absence of progressive disease.

Results

Forty-three patients were treated. After a median of 13 cycles (range, 1 to 71 cycles), select treatment-related toxicities included hypertension (58%; grades 2 and 3 in 19% and 26%), proteinuria (67%; grades 2 and 3 in 14% and 19%), headache (51%; grades 2 and 3 in 16% and 7%), fatigue (74%; grades 2 and 3 in 19% and 2%), and joint pain (63%; grades 2 and 3 in 19% and 0%). Eighty-four percent of patients had at least stable disease on an NSAI, confounding efficacy results. Partial responses were seen in 9% of patients and stable disease ≥ 24 weeks was noted in 67%. Median PFS was 17.1 months.

Conclusion

Combination letrozole and bevacizumab was feasible with expected bevacizumab-related events of hypertension, headache, and proteinuria. Phase III proof-of-efficacy trials of endocrine therapy plus bevacizumab are in progress (Cancer and Leukemia Group B 40503).

INTRODUCTION

Two-thirds of breast cancers express the estrogen receptor, and endocrine therapy with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) is widely used as treatment for patients with both early and advanced-stage hormone receptor–positive disease.1–6 Despite advances in hormonal therapy, some women will develop recurrent breast cancer and will ultimately die of endocrine-resistant disease.7,8 Recent insights into the complex interactions between the estrogen receptor and other signal transduction pathways have suggested potential mechanisms of endocrine therapy resistance.9,10 There is emerging evidence to support the role of angiogenesis as another mechanism for resistance to endocrine therapy.

Estrogen directly modulates angiogenesis under both physiologic and pathologic conditions. The cyclical neovascularization of the female reproductive tract in premenopausal women is one of the few active sites of angiogenesis in adult organisms under normal conditions and suggests a potent angiogenic effect of estradiol.11 In preclinical models, estradiol stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and migration in human umbilical vein endothelial cell cultures.12 In addition, endothelial cell growth is inhibited by antiestrogen therapy with tamoxifen and fulvestrant.13 Estrogen-induced angiogenesis is mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein that plays a critical role in the growth of blood vessels.14 Estradiol increases VEGF expression in the rat uterus, leading to increased vascular permeability and uterine edema.15

Estradiol has a similar effect on angiogenesis in breast cancer models. Estrogen increases VEGF in MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines,16 whereas reduction of estrogen with AIs reduced VEGF in a carcinogen-induced, hormone-dependent mouse model.17 The most compelling evidence for the relationship between angiogenesis and endocrine regulation derives from xenograft data, in which castration in a male mouse model of androgen-dependent breast cancer led to tumor shrinkage and vascular regression.18 However, endocrine resistance emerged in this tumor model and was heralded by a wave of neovascularization and tumor regrowth. On a molecular level, castration initially causes a reduction in VEGF mRNA levels that parallels tumor and vascular regression. At the time of tumor regrowth, VEGF mRNA levels simultaneously rebound. Interestingly, castration in this model led to endothelial cell apoptosis before tumor cell apoptosis, supporting a direct effect of endocrine therapy on tumor vasculature.

In patients with breast cancer, retrospective studies indicate that high VEGF levels in breast tumor tissue are associated with decreased responsiveness to endocrine therapy in both the adjuvant and metastatic settings.19,20 Therefore, we hypothesized that anti-VEGF therapy may delay or prevent the onset of endocrine therapy resistance in patients with hormone-sensitive breast cancer.

Bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF, has modest single-agent activity in patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC)21 and, in combination with weekly paclitaxel, prolongs progression-free survival (PFS) in the first-line setting.22 We report a feasibility study of bevacizumab plus endocrine therapy with letrozole, a nonsteroidal AI (NSAI), in patients with hormone receptor–positive MBC.

METHODS

Patient Eligibility

Forty-three patients with MBC were enrolled at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the University of California San Francisco Comprehensive Cancer Center from September 2004 through March 2006. Patients with histologically confirmed breast carcinoma were eligible if they had ER- and/or progesterone receptor–positive, unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease and had received two or fewer chemotherapy regimens for treatment of advanced-stage disease. Any number of prior endocrine therapies was allowed. Eligible patients were either postmenopausal or received ovarian suppression. Patients may have had stable or responding disease on prior NSAI therapy.

Additional eligibility criteria included measurable or nonmeasurable disease, as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)23; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤ 2; and adequate hepatic, renal, and hematologic function. Exclusion criteria included ≤ 3 weeks of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, or investigational therapy or ≤ 2 weeks of hormonal therapy before initiating study treatment (except for those already receiving an NSAI). Prior therapy with a steroidal AI (eg, exemestane) was not permitted unless it was administered in the adjuvant setting and ≥ 12 months had elapsed since last treatment. All patients had baseline computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, and those with CNS disease, including brain metastases or history of stroke, were ineligible. Prior treatment with VEGF or VEGF receptor (VEGFR) inhibitors, major surgery ≤ 28 days before treatment, and baseline proteinuria at more than 500 mg/24 hours were additional exclusion criteria. Patients with clinically significant cardiovascular disease (eg, uncontrolled hypertension, myocardial infarction, unstable angina), history of arterial thrombotic events ≤ 6 months before study entry, or current use of anticoagulation drugs were excluded. The institutional review boards of the participating centers approved this protocol. All patients gave written informed consent.

Study Design and Treatment

This was a nonrandomized open-label feasibility trial conducted at two institutions. The primary objective was to determine the safety of letrozole plus bevacizumab in the treatment of MBC. Secondary end points included response rate, clinical benefit rate (complete response + partial response [PR] + stable disease [SD] ≥ 24 weeks), PFS, and duration of response.

Letrozole 2.5 mg was administered orally on a continuous daily schedule. Bevacizumab 15 mg/kg was administered intravenously every 3 weeks, with a treatment window of ± 5 days. For patients already receiving NSAIs on study entry, letrozole was required by study and bevacizumab was added on enrollment. Bisphosphonate use was permitted during study therapy. Proteinuria was monitored by either dipstick urinalysis or urine protein to creatinine ratio every 3 weeks before bevacizumab administration. If a dipstick urinalysis was the chosen method and the urine protein increased by one point (eg, from 0 to 1+), a 24-hour urine sample was required to quantitate the amount of protein in 24 hours. Grade 3 proteinuria was defined as either a 24-hour urine with ≥ 3.5 g of protein or a protein to creatinine ratio ≥ 3.5.

Patients were treated until disease progression or unacceptable adverse events. There were no dose modifications of letrozole or bevacizumab during this study. For grade 3 or 4 bevacizumab-related toxicities, bevacizumab was held until symptoms resolved to grade ≤ 1, but letrozole was continued. Patients with grade 3 hypertension controlled by oral medications were allowed to continue bevacizumab.

Patient Evaluation

Patients were evaluated for toxicity at the time of each 3-week treatment cycle, according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0 (NCI-CTC v3.0). Radiographic response was evaluated every 12 weeks with radiographic scans that were reviewed at each site by a designated study radiologist, according to RECIST criteria.

Statistical Considerations

The primary end point of this trial was safety. Toxicity rate was defined as the proportion of patients with grade 4 toxicities, excluding grade 4 thrombosis/embolism. A Simon optimal two-stage design was used.24 A 5% grade 4 toxicity rate was considered safe, and a 20% grade 4 toxicity rate was considered not safe. This design allows early study termination for excessive toxicity, because a Simon two-stage design with an efficacy end point would allow early termination for inefficacy. The probabilities of type I and type II errors were set at 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. Nineteen patients were accrued to the first stage, and if two or fewer patients experienced grade 4 toxicity, 24 patients would enroll on the second stage. If fewer than five of the 43 patients experienced grade 4 toxicities (excluding grade 4 thrombosis/embolism), this regimen would be considered worthy of further testing. Patients with MBC are at increased risk for thromboembolic events on the basis of their underlying diagnosis of breast cancer alone; therefore, these events were excluded from the statistical primary end point of grade 4 toxicity. However, if more than four patients had experienced grade 4 thrombosis/embolism at any point during this trial, further patient accrual would have been suspended.

Toxicities were summarized using NCI-CTC v3.0, and the maximum grade per patient was used as the summary measure. There were several secondary end points. Overall response rate and clinical benefit rate were calculated with exact 95% CIs. PFS and time to treatment failure were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methods. PFS was defined as being from start of therapy to progression of disease or last date of follow-up. Time to treatment failure was defined as being from start of therapy to toxicity, progression of disease, or last date of follow-up.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

Forty-three patients were enrolled and treated on study (Table 1). All patients were evaluable for toxicity and response. Table 2 summarizes systemic therapy for these 43 study participants before study enrollment. Thirteen patients (30%) had undergone ovarian suppression or oophorectomy for either adjuvant or metastatic disease.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 43)

| Characteristic | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 50 | |

| Range | 32-77 | |

| ECOG performance status, grade | ||

| Median | 0 | |

| Range | 0-1 | |

| Hormone receptor status | ||

| ER positive | 43 | 100 |

| PR positive | 32 | 74 |

| HER2 positive (IHC 3+ or FISH amplified) | 2 | 5 |

| Sites of metastases | ||

| Bone only | 11 | 26 |

| Chest wall/soft tissue/lymph nodes | 19 | 44 |

| Visceral (lung or liver) | 23 | 53 |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IHC, immunohistochemistry; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization.

Table 2.

Prior Systemic Therapy (N = 43)

| Treatment for Metastatic Disease | No. of Patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Any prior endocrine therapy | 40 | 93 |

| Prior NSAI leading to enrollment onto study* | 36 | 84 |

| Any prior chemotherapy | 3 | 7 |

| Adjuvant therapy | 30 | 70 |

| Chemotherapy | 29 | 67 |

| Endocrine therapy | 24 | 56 |

| Tamoxifen | 23 | 53 |

| Aromatase inhibitor | 1 | 2 |

Abbreviation: NSAI, nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor.

Median time on NSAI prior to study enrollment was 15 weeks (range, 1 to 216 weeks).

Adverse Events

After a median of 13 cycles (range, 1 to 71 cycles), the most common drug-related toxicities included fatigue (74%; grades 2 and 3, 19% and 2%), proteinuria (67%; grades 2 and 3, 14% and 19%), joint pain (63%; grades 2 and 3, 19% and 0%), hypertension (58%; grades 2 and 3, 19% and 26%), and headache (51%; grades 2 and 3, 16% and 7%) (Table 3). Hot flashes were reported in 30% of patients (grades 2 and 3, 9% and 0%). Hemorrhage was rare (grades 2 and 3, 2% and 2%).

Table 3.

Select Drug-Related Toxicities (N = 43)

| Adverse Event | All Grades |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | No. of Patients | % | |

| Hyponatremia | 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Hypertension | 25 | 58 | 8 | 19 | 11 | 26 | 0 | |

| Fatigue | 32 | 74 | 8 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Joint pain | 27 | 63 | 8 | 19 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Headache | 22 | 51 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 7 | 0 | |

| Proteinuria | 29 | 67 | 6 | 14 | 8 | 19 | 0 | |

| Vomiting | 12 | 28 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 0 | |

| Depression | 5 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| Diarrhea | 17 | 40 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 0 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 9 | 21 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | |

| Hot flashes | 13 | 30 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Osteonecrosis | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Epistaxis | 12 | 28 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

Grade 3 proteinuria, seen in 19% of patients (n = 8), developed after a median of 24.5 months (range, 4 to 38 months) of therapy. Three of these patients discontinued study therapy because of proteinuria at 5, 12, and 26 months. Three patients receiving angiotensin receptor blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors remain on study with improvement of their proteinuria. Two patients were removed from the study for disease progression. All eight patients with grade 3 proteinuria had hypertension (grades 2 and 3, 12.5% and 87.5%). No patients with grade 3 proteinuria experienced hypoalbuminemia or grade 4 proteinuria (nephrotic syndrome). Five patients received bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid [ZA], three patients; pamidronate, two patients). Three patients who discontinued bevacizumab had improvement of proteinuria to grade 1 in 3, 3, and 5 months.

One patient required a dose delay of letrozole because of drug-related toxicity (grade 2 joint pain). Fifteen patients had delays of bevacizumab for drug-related toxicities, including proteinuria (n = 10), hypertension (n = 4), and fatigue (n = 4). Two patients developed osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) while receiving protocol therapy and ZA, requiring delays in bevacizumab dosing. Ten months after beginning ZA, one patient developed ONJ 5 months after tooth extraction, despite discontinuation of ZA before the procedure. The second patient developed spontaneous ONJ after 34 months of ZA treatment.

There were four potentially treatment-related serious adverse events. Grade 3 hypertension led to the hospitalization of two patients; one patient experienced grade 4 hyponatremia due to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, which may have been exacerbated by the use of a diuretic to manage bevacizumab-related hypertension. One patient with known gastric varices secondary to pseudocirrhosis and portal hypertension was hospitalized with hematemesis; she underwent endoscopy with variceal banding, received blood product support, and continued on study on recovery. This patient eventually developed grade 3 thrombocytopenia and was taken off study.

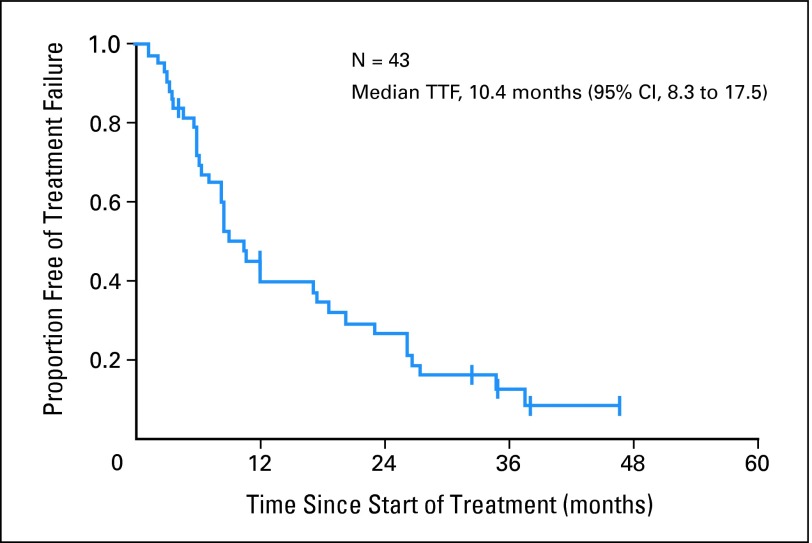

Nine patients discontinued therapy because of drug-related toxicities: grade 3 hypertension (n = 3), grade 3 proteinuria (n = 3), grade 3 headache (n = 1), grade 4 hyponatremia (n = 1), and grade 3 thrombocytopenia associated with portal hypertension (n = 1). Three patients withdrew from protocol therapy for other reasons: one had definitive surgery with mastectomy after 17 cycles of study therapy for an initially unresectable locally advanced breast cancer at the time of study entry, and two withdrew informed consent. The median time to treatment failure was 10.4 months (95% CI, 8.3 to 17.5 months) (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of time to treatment failure (TTF).

Efficacy

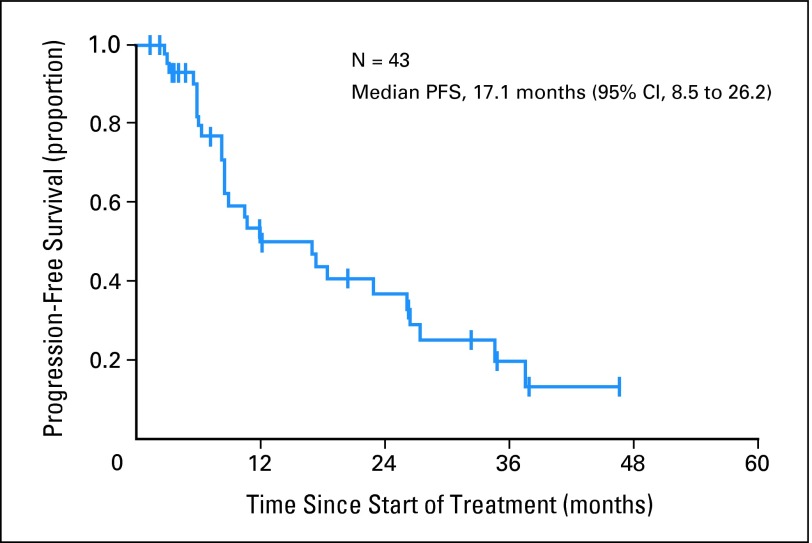

Efficacy was a secondary end point of the study. Bevacizumab was added to ongoing NSAI therapy in 84% of patients (median duration of prior AI therapy, 15 weeks; range, 1 to 216 weeks). All 43 patients were evaluable for response. Four patients had PR as best response on treatment, and there were no complete responses, for a response rate of 9% (95% CI, 3% to 22%). Twenty-nine patients had SD for ≥ 24 weeks. Therefore, the clinical benefit rate (PR + SD ≥ 24 weeks) was 77% (95% CI, 61% to 88%). Six patients had SD for less than 24 weeks but discontinued study therapy for reasons other than disease progression. The remaining four patients had progressive disease as best response. Four patients with SD remained on study therapy at 38, 41, 44, and 53+ months. The median PFS was 17.1 months (95% CI, 8.5 to 26.2 months; Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of progression-free survival (PFS).

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the results of our trial, treatment with letrozole plus bevacizumab is feasible in postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor–positive MBC. The most common treatment-related adverse events were hypertension, proteinuria, fatigue, and joint pain. An additional clinically significant toxicity was ONJ; patients who experienced ONJ were also receiving ZA.

Bevacizumab-associated adverse events are well described and include arterial thrombosis, wound-healing complications, GI perforation, bleeding, hypertension, and proteinuria.25 A recent meta-analysis of randomized, controlled bevacizumab-containing trials reported hypertension in 3% to 36% of patients and proteinuria in 21% to 63% of patients.26 Of these bevacizumab-treated patients, nephrotic-range proteinuria (NCI-CTC grade 3, > 3.5 g/24 hours) was noted in 1% to 2% of patients, and grade 3 hypertension was detected in 12%. The degree of proteinuria was dependent on the administered dose of bevacizumab, with higher doses, such as those used in this trial, associated with a greater degree of proteinuria.

In our study, grade 3 proteinuria and hypertension were seen in 19% and 26% of patients, respectively. Grades 2 and 3 hypertension (rates of 28% each) were observed in a neoadjuvant pilot trial of letrozole and bevacizumab in 22 patients with early-stage, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer,27 and two patients discontinued bevacizumab because of uncontrolled hypertension. However, unlike in this study, proteinuria was rare, with grade 1 toxicity occurring in 8% of patients. The higher rate of grade 3 proteinuria in our study could be attributed to duration of therapy and combined toxicity from NSAIs and/or bisphosphonates. Patients on this study received a median of 13 cycles (range, 1 to 71 cycles), with a median time to treatment failure of 10.4 months. Patients in the small neoadjuvant study received ≤ 24 weeks of treatment on the basis of in-breast tumor response. In a second trial, bevacizumab was added to current hormone treatment for 21 patients with progressive hormone receptor–positive MBC in an attempt to overcome endocrine resistance, with only 38% receiving letrozole as endocrine therapy.28 After a median of 12 weeks, grades 2 and 3 hypertension occurred in 19% and 5% of patients, respectively, and grades 1 and 2 proteinuria occurred in 19% and 5%, respectively.

Another possible explanation for the higher rates of bevacizumab-associated hypertension and proteinuria seen in this trial is that letrozole may be a contributing factor. Randomized studies of single-agent letrozole do not suggest increased rates of hypertension when compared with tamoxifen, but an interaction between letrozole and bevacizumab cannot be excluded.6,29,30 Recently, germline polymorphisms in the VEGF and VEGFR-2 genes were analyzed in a phase III trial of paclitaxel plus bevacizumab in MBC (E2100). In this trial, 14.8% and 3.5% of patients in the bevacizumab-containing arm experienced grade 3 or 4 hypertension and proteinuria, respectively (NCI-CTC, v2.0).22 Two variant VEGF genotypes (VEGF-1498 TT and VEGF-634 CC) were associated with lower rates of grades 3 and 4 hypertension in the bevacizumab-containing arm (P = .022 and P = .005, respectively).31 Of particular interest, bevacizumab-treated patients who experienced grades 3 and 4 hypertension were a subgroup with longer median survival compared with bevacizumab-treated patients with no hypertension (38.7 v 25.3 months, respectively; P = .002). Therefore, it is possible that host-related variability in study participants may contribute to differing rates of toxicity and efficacy for patients receiving VEGF-targeted therapy.

The pathogenesis of bevacizumab-associated hypertension and renal toxicity is poorly understood; however, one clinical study has suggested an association between the occurrence of these adverse events.32 VEGF under physiologic conditions stimulates the production of nitric oxide and prostacyclin by endothelial cells, and these proteins serve as mediators of vasodilation.33 Therefore, decreased nitric oxide or prostacyclin levels may cause increased peripheral vascular resistance and increased blood pressure. VEGF is important for maintaining glomerular endothelial health. Recent data suggest that inhibition of local VEGF in glomerular podocytes leads to renal thrombotic microangiopathy with proteinuria.34 These nephrotoxic effects appear reversible in the majority of patients on discontinuation of therapy. The transient nature of these changes is similar to the clinical course of proteinuria and hypertension in patients with preeclampsia. Preeclamptic patients have elevated levels of a soluble form of VEGFR-1 (sVEGFR-1) that is released from the placenta. sVEGFR-1 forms complexes with VEGF and placental growth factor. Preeclampsia usually resolves with delivery of the sVEGFR-1–rich placenta.35 In our study, bevacizumab-induced proteinuria improved shortly after the discontinuation of study therapy.

The appropriate management of hypertension and proteinuria will be important for the feasibility of bevacizumab-containing treatment paradigms. Physicians should remain cautious about adverse events reported with combination anti-VEGF therapies, because some toxicity may be potentiated by antiangiogenic effects. For example, ONJ was reported in two patients treated with letrozole plus bevacizumab and ZA in our study. Although ONJ is well described in bisphosphonate-treated patients,36 it is unclear whether bevacizumab may cause or exacerbate this toxicity through impaired wound healing.37,38 The patients who developed ONJ discontinued ZA but remained on protocol therapy with letrozole and bevacizumab. One of these patients has had stable ONJ despite continued protocol therapy for 53+ months. An ongoing prospective registry study of bisphosphonate-treated patients will provide a more definitive setting to evaluate a potential interaction between bevacizumab and bisphosphonate therapy.

It is impossible to discern the efficacy of letrozole plus bevacizumab from these data because eligible patients were permitted to have had SD from prior treatment with an NSAI. Nevertheless, the PFS of this study (17.1 months) compares favorably with the 9-month PFS in postmenopausal women with MBC treated with letrozole in the first-line setting.6

Supported by preclinical data and the feasibility of combination letrozole plus bevacizumab, the hypothesis that anti-VEGF therapy can delay resistance to endocrine therapy is being tested in an ongoing proof-of-efficacy phase III Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) –led multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial (CALGB 40503). This study is enrolling patients with hormone receptor–positive MBC to first-line endocrine therapy (letrozole or tamoxifen) with or without bevacizumab. Although the primary end point is PFS, secondary end points will address toxicity. A pharmacogenomic assessment will explore variants in the VEGF gene that may predict response to therapy and toxicity. Other ongoing studies include trials of fulvestrant plus bevacizumab and endocrine therapy plus VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors.39

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Jodi Spiegel Fisher Foundation, Novartis, and Genentech. Support for third-party manuscript formatting and copyediting provided by Genentech.

Presented in part at the 41st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 13-17, 2005, Orlando, FL; San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 8-11, 2005, San Antonio, TX; and 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 2-6, 2006, Atlanta, GA.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00305825.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Tiffany A. Traina, Roche (C), Genentech (C); Michelle E. Melisko, Genentech (C); John W. Park, Genentech (C); Andrew D. Seidman, Genentech (C); Diana Lake, Novartis (C), Genentech (C); Chau Dang, Genentech (C); Clifford A. Hudis, Genentech (C); Maura N. Dickler, Genentech (C), Roche (C), Novartis (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Tiffany A. Traina, Roche, Genentech; Michelle E. Melisko, Novartis, Genentech, Roche; John W. Park, Roche, Novartis, Genentech; Andrew D. Seidman, Genentech; Monica Fornier, Genentech; Diana Lake, Novartis, Genentech; Chau Dang, Genentech, Roche; Maria Theodoulou, Genentech; Clifford A. Hudis, Roche; Maura N. Dickler, Roche Research Funding: Hope S. Rugo, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech; Andrew D. Seidman, Genentech; Chau Dang, Genentech; Maria Theodoulou, Genentech; Maura N. Dickler, Genentech, Novartis Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Tiffany A. Traina, Hope S. Rugo, Clifford A. Hudis, Maura N. Dickler

Financial support: Clifford A. Hudis

Administrative support: Matthew Paulson, Jill Grothusen, Larry Norton, Clifford A. Hudis

Provision of study materials or patients: Hope S. Rugo, Michelle E. Melisko, John W. Park, Andrew D. Seidman, Monica Fornier, Diana Lake, Chau Dang, Mark Robson, Maria Theodoulou, Clifford A. Hudis, Maura N. Dickler

Collection and assembly of data: Tiffany A. Traina, Hope S. Rugo, James F. Caravelli, Sujata Patil, Stephanie Geneus, Matthew Paulson, Jill Grothusen, Chau Dang, Clifford A. Hudis, Maura N. Dickler

Data analysis and interpretation: Tiffany A. Traina, Hope S. Rugo, Sujata Patil, Benjamin Yeh, Carlos D. Flombaum, Larry Norton, Clifford A. Hudis, Maura N. Dickler

Manuscript writing: Tiffany A. Traina, Hope S. Rugo, Sujata Patil, Carlos D. Flombaum, Clifford A. Hudis, Maura N. Dickler

Final approval of manuscript: Tiffany A. Traina, Hope S. Rugo, James F. Caravelli, Sujata Patil, Benjamin Yeh, Michelle E. Melisko, John W. Park, Stephanie Geneus, Matthew Paulson, Jill Grothusen, Andrew D. Seidman, Monica Fornier, Diana Lake, Chau Dang, Mark Robson, Maria Theodoulou, Carlos D. Flombaum, Larry Norton, Clifford A. Hudis, Maura N. Dickler

REFERENCES

- 1.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1081–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: First results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2131–2139. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thurlimann B, et al. Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: Update of study BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:486–492. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1793–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabholtz JM, Buzdar A, Pollak M, et al. Anastrozole is superior to tamoxifen as first-line therapy for advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women: Results of a North American multicenter randomized trial. Arimidex Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3758–3767. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.22.3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mouridsen H, Gershanovich M, Sun Y, et al. Phase III study of letrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women: Analysis of survival and update of efficacy from the International Letrozole Breast Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2101–2109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and a 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewster AM, Hortobagyi GN, Broglio KR, et al. Residual risk of breast cancer recurrence 5 years after adjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1179–1183. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massarweh S, Schiff R. Unraveling the mechanisms of endocrine resistance in breast cancer: New therapeutic opportunities. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1950–1954. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osborne CK, Shou J, Massarweh S, et al. Crosstalk between estrogen receptor and growth factor receptor pathways as a cause for endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:865s–870s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Losordo DW, Isner JM. Estrogen and angiogenesis: A review. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:6–12. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morales DE, McGowan KA, Grant DS, et al. Estrogen promotes angiogenic activity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro and in a murine model. Circulation. 1995;91:755–763. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagliardi AR, Hennig B, Collins DC. Antiestrogens inhibit endothelial cell growth stimulated by angiogenic growth factors. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:1101–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazi AA, Jones JM, Koos RD. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of gene expression in the rat uterus in vivo: Estrogen-induced recruitment of both estrogen receptor alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 to the vascular endothelial growth factor promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2006–2019. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takei H, Lee ES, Jordan VC. In vitro regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by estrogens and antiestrogens in estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2002;9:39–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02967545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura J, Savinov A, Lu Q, et al. Estrogen regulates vascular endothelial growth/permeability factor expression in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a) anthracene-induced rat mammary tumors. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5589–5596. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain RK, Safabakhsh N, Sckell A, et al. Endothelial cell death, angiogenesis, and microvascular function after castration in an androgen-dependent tumor: Role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10820–10825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manders P, Beex LV, Tjan-Heijnen VC, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with the efficacy of endocrine therapy in patients with advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:2125–2132. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linderholm B, Grankvist K, Wilking N, et al. Correlation of vascular endothelial growth factor content with recurrences, survival, and first relapse site in primary node-positive breast carcinoma after adjuvant treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1423–1431. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cobleigh MA, Langmuir VK, Sledge GW, et al. A phase I/II dose-escalation trial of bevacizumab in previously treated metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:117–124. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roodhart JM, Langenberg MH, Witteveen E, et al. The molecular basis of class side effects due to treatment with inhibitors of the VEGF/VEGFR pathway. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2008;3:132–143. doi: 10.2174/157488408784293705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X, Wu S, Dahut WL, et al. Risks of proteinuria and hypertension with bevacizumab, an antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:186–193. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forero-Torres A, Galleshaw J, Jones C, et al. A pilot open-label trial of preoperative (neoadjuvant) letrozole in combination with bevacizumab in postmenopausal women with newly diagnosed operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl):37s. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2010.n.035. abstr 625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falkson C, Rossman JF, Nabell L, et al. A phase II trial investigating if bevacizumab in combination with hormone therapy will reverse acquired estrogen independence in metastatic breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl):59s. abstr 1074. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mouridsen H, Keshaviah A, Coates AS, et al. Cardiovascular adverse events during adjuvant endocrine therapy for early breast cancer using letrozole or tamoxifen: Safety analysis of BIG 1-98 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5715–5722. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buzdar A, Douma J, Davidson N, et al. Phase III, multicenter, double-blind, randomized study of letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, for advanced breast cancer versus megestrol acetate. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3357–3366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider BP, Wang M, Radovich M, et al. Association of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 genetic polymorphisms with outcome in a trial of paclitaxel compared with paclitaxel plus bevacizumab in advanced breast cancer: ECOG 2100. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4672–4678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller KD, Chap LI, Holmes FA, et al. Randomized phase III trial of capecitabine compared with bevacizumab plus capecitabine in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:792–799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, et al. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, et al. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1129–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsatsaris V, Goffin F, Munaut C, et al. Overexpression of the soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor in preeclamptic patients: Pathophysiological consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5555–5563. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estilo CL, Van Poznak CH, Wiliams T, et al. Osteonecrosis of the maxilla and mandible in patients with advanced cancer treated with bisphosphonate therapy. Oncologist. 2008;13:911–920. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Estilo CL, Fornier M, Farooki A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw related to bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4037–4038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McArthur HL, Estilo C, Huryn J, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) among intravenous (IV) bisphosphonate- and/or bevacizumab-treated patients (pts) at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl):523s. abstr 9588. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramaniam DS, Wilkinson M, Liu M, et al. Sorafenib in hormone-receptor positive metastatic breast cancer resistant to aromatase inhibitors. Presented at the 2008 Breast Cancer Symposium; September 5-7, 2008; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]