Abstract

Background and purpose

Internal fixation (IF) in femoral neck fractures has high reoperation rates and some predictors of failure are known, such as age, quality of reduction, and implant positioning. Finding new predictors of failure is an ongoing process, and in this study we evaluated the importance of low bone mineral density (BMD).

Patients and methods

140 consecutive patients (105 females, median age 80) treated with IF had a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan of the hip performed median 80 days after treatment. The patients’ radiographs were evaluated for fracture displacement, implant positioning, and quality of reduction. From a questionnaire completed during admission, 2 variables for comorbidity and walking disability were chosen.

Primary outcome was low hip BMD (amount of mineral matter per square centimeter of hip bone) compared to hip failure (resection, arthroplasty, or new hip fracture). A stratified Cox regression model on fracture displacement was applied and adjusted for age, sex, quality of reduction, implant positioning, comorbidity, and walking disability.

Results

49 patients had a T-score below –2.5 (standard deviation from the young normal reference mean) and 70 patients had a failure. The failure rate after 2 years was 22% (95% CI: 12–39) for the undisplaced fractures and 66% (CI: 56–76) for the displaced fractures. Cox regression showed no association between low hip BMD and failure. For the covariates, only implant positioning showed an association with failure.

Interpretation

We found no statistically significant association between low hip BMD and fixation failure in femoral neck fracture patients treated with IF.

Internal fixation (IF) for femoral neck fracture has many advantages such as minimal blood loss, short operating time, and low infection rate (Rogmark and Johnell 2006). The trend is, however, to treat displaced fractures with hemiarthroplasty due to a high reoperation rate of IF in comparison to arthroplasty (40% vs. 11%), and also due to better functional outcome (Parker and Gurusamy 2006). The high reoperation rate is mainly due to early failure of fixation.

There are several factors that can lead to an increased risk of failure. The most important is fracture displacement, which leads to 11% failure in undisplaced fractures and 40% failure in displaced fractures (Parker and Gurusamy 2006, Gjertsen et al. 2011). There is an increased risk of non-union with older age (Parker et al. 2007), poor quality of reduction (Schep et al. 2004, Heetveld et al. 2007), and poor implant positioning (Schep et al. 2004). Low BMD may be another predictor of failure. Low BMD is a well-defined risk factor for hip fracture (Kanis et al. 2008) and experimentally, several studies have shown that low BMD affects the strength of osteosynthesis (Sjostedt et al. 1994, Bonnaire et al. 2005). In addition, low BMD appears to delay fracture healing but the association between low BMD and failure in clinical studies is more uncertain (Giannoudis et al. 2007).

Karlsson et al. (1996) and Heetveld et al. (2005) found no association between low BMD and failure, but the known predictors of failure were not adjusted for in these studies. The only study that used all the known potential confounders in the analysis was Spangler et al. (2001). However, this study was retrospective and used the osteoporosis diagnosis from a register. We evaluated the effects of low BMD on failure of femoral neck fractures treated with IF while adjusting for known predictors of failure.

Patients and methods

Patients

In the period January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2006, a prospective consecutive study on systematic tertiary prevention of osteoporotic fractures (prevention of new fracture after low-energy fracture) was conducted at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Odense University Hospital (Ryg 2009). This study included all hip fracture patients over 45 years of age and was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans. It was approved by the Danish Data Protection Board (entry no. 2010-41-5194).

The exclusion criteria were (1) cognitive impairment: the patient could not understand the information given by the enrolling person; (2) serious illness: the enrolling person assessed whether the patient could benefit from osteoporosis treatment (i.e. sufficient length of expected survival to experience treatment effect); (3) high-energy fracture; and (4) pathological fracture.

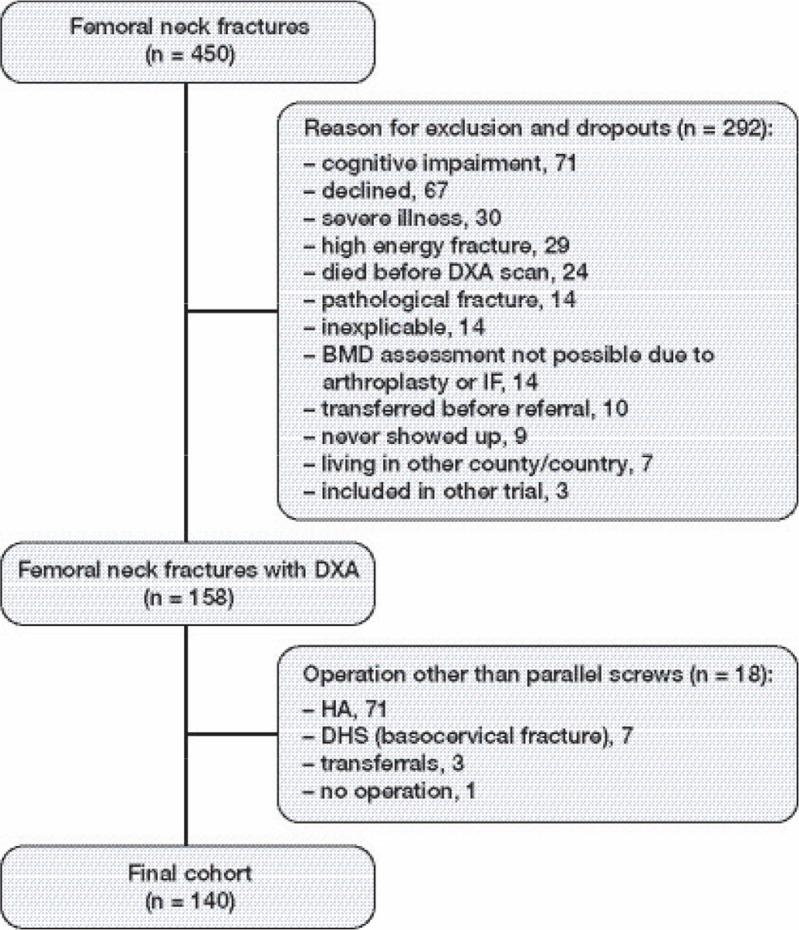

In that study, 450 consecutive femoral neck fracture patients were treated and therefore eligible for a DXA scan. Of these, 292 patients were excluded mainly due to cognitive impairment or severe illness, or because they declined to participate. Thus, 158 femoral neck fracture patients with DXA scan were eligible for inclusion in this study, with information on age (dichotomous variable divided at 70 years), sex, BMD, and 20 variables from a questionnaire. 18 other patients were treated with an implant other than standard IF (Uppsala screws), so the final cohort consisted of 140 patients (Figure 1). The median age of the patients was 80 years and 105 patients were female (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient enrollment. DXA: Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; BMD: bone mineral density; HA: hemiarthroplasty; DHS: dynamic hip screw.

Table 1.

Key patient demographics for 140 patients

| No failure | Failure | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 70 | 70 | 140 |

| Age (IQR) | 82 (73–86) | 79 (70–84) | 80 (70–85) |

| Sex M / F | 21 / 49 | 14 / 56 | 35 /105 |

| Undisplaced fracture | 32 | 10 | 42 |

| Displaced fracture | 38 | 60 | 98 |

| Total hip T-score > –2.5 | 45 | 46 | 91 |

| Total hip T-score ≤ –2.5 | 25 | 24 | 49 |

All radiographs from the total cohort were evaluated by the first author to ensure correct fracture diagnosis. Any discrepancy between the primary report and the review was discussed with at least 1 of the other authors, and a final consensus opinion was obtained.

Methods

Data for follow-up

Information on operation date, reoperation, death, and type of operation was retrieved retrospectively from the county-based patient administration system and radiographs. All the patients were treated with closed reduction and IF using 2 Uppsala screws, regardless of fracture displacement or age. All patients were primarily operated or supervised by a senior registrar. Postoperatively, full weight bearing exercises from day 1 were encouraged and similar drugs for thrombosis prophylaxis and antibiotics were administered. Routine clinical and radiographic fracture follow-up was performed after 4 months. Failure was defined as any procedure that led to major reoperation with change/loss of IF or new fracture, although isolated removal of IF was not classified as failure. A new fracture was defined as subtrochanteric at the level of an IF implant or a femoral neck fracture more than 1 year after removal of IF. Of the 140 patients analyzed, 68 had failure as defined above, and by extracting the equivalent data from the Danish National Registry of Patients (NRP), 2 other patients with reoperations were located in another county. The NRP search included all diagnoses and procedures that might have led to loss of a hip implant or to a new hip fracture.

BMD

Ryg (2009) conducted a questionnaire during patient admission, and eligible patients were referred for a DXA scan, which was performed median 80 (IQR: 60–101) days after treatment. This led to exclusion of 24 patients due to death, and 9 patients failed to attend. The contralateral hip was used for the DXA scan and 14 patients had to be excluded due to an already existing arthroplasty or IF implant in that hip (Figure 1). The DXA scanner was a Hologic Discovery and NHANES III was used as reference material (Looker et al. 1998). Low BMD level using total hip and neck BMD was defined as a T-score of ≤ –2.5 (Kanis et al. 2008). 49 patients had a total hip BMD score of less than –2.5 (Table 1). Data from the spine measurements were not included because our aim was to investigate low BMD in relation to failure where the IF was inserted. Prior to the primary surgical treatment, 31 patients were treated with calcium and vitamin D and all patients were discharged with a prescription for calcium and vitamin D. No other osteoporosis treatments were administered during the period between the operation and the DXA scan, and bisphosphonate, strontium, or PTH was given after diagnosis of osteoporosis.

Radiographs

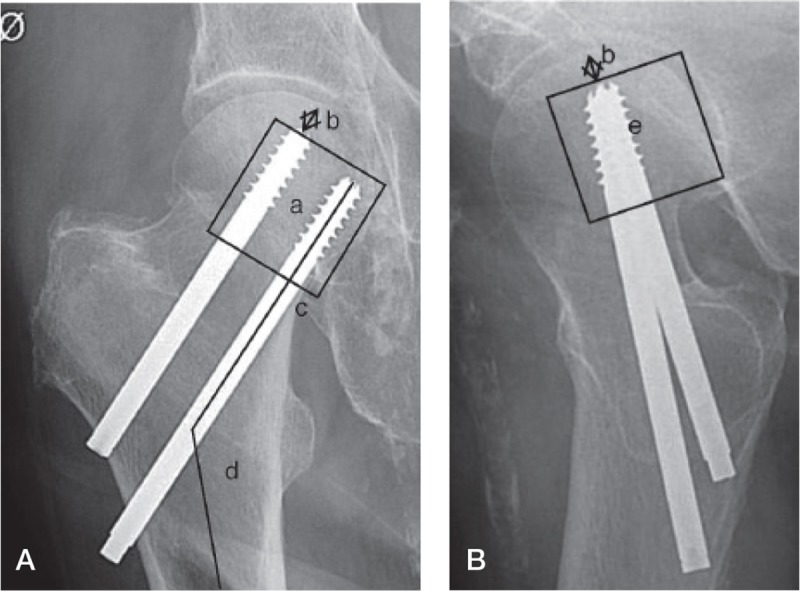

All images were evaluated before the statistical analysis for fracture displacement, implant positioning, and quality of reduction. Fracture displacement was assessed using the simplified undisplaced vs. displaced version of the Garden criteria (Parker 1993), due to low reliability of the 4-grade system (Van Embden et al. 2012). The implant positioning was assessed according to a modified version by Schep et al. (2004) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Assessment of implant positioning. A. Anterior-posterior view. B. Axial view.

a: position of screws in the central/caudal segment;

b: distance of screw tip to the articular margin;

c: position of the lowest screw directly above calcar;

d: angle of screws;

e: position of screws in the central/posterior segment.

1 point was given if: (1) the positions of the screws were within the central or caudal segment of the femoral head on the anterior-posterior view; (2) the distance between the tip of the screws and the articular margin of the femoral head was less than 10 mm; (3) the positioning of the lowest screw was directly over the calcar in anterior-posterior view: (4) the angle of the screws and the femur was more than 130 degrees; (5) the positions of the screws were within the central or dorsal part on the axial view.

A score of 4 points (maximum 5) was considered to be adequate implant positioning. For the analysis, the positioning variable is therefore dichotomous (adequate or inadequate). In the original study by Schep et al. (2004), the score consisted of 6 points; a final point was given if the screw position in the axial view was placed near the posterior cortex. The guideline in our department was to align the screws in the center, and the score was therefore limited to the above-mentioned 5 points.

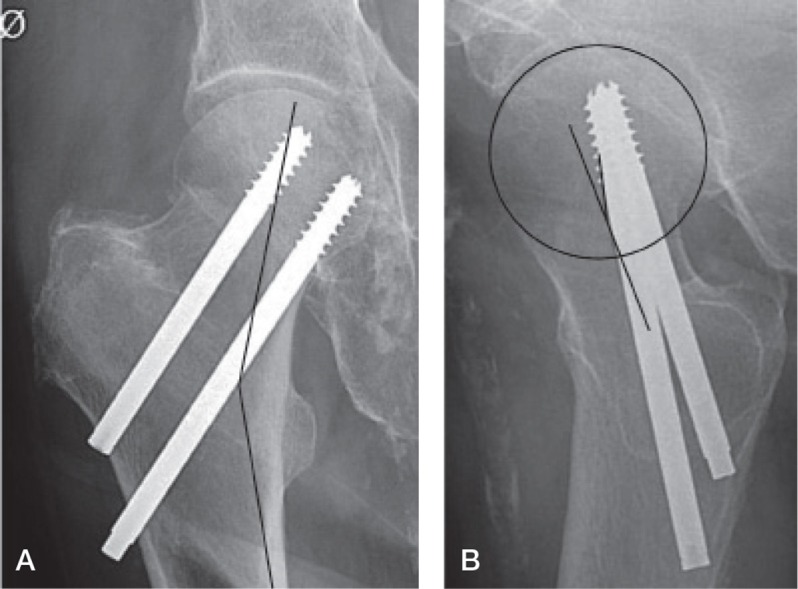

A modified Garden’s alignment index (Frandsen 1979) was used to assess the quality of reduction (Figure 3). On the AP view, the central axis of the medial group of trabeculae in the capital fragment and the line of the medial femoral cortex was used to determine an angle. On the axial view, the anterior or posterior angulation of the head was measured from the angle between a line drawn from the midpoint of the fracture surface of the distal fragment to the center of the femoral head and a line through the central axis of the neck of the femur. In order for the reduction to be acceptable, the anterior-posterior angle should be between 150 and 189 degrees and the axial angle should be less than 20 degrees. Frandsen (1979) used 2 axial angle cutpoints (15 and 25 degrees) whereas we used one cutpoint (20 degrees), which was a predictor of failure in the study by Palm et al. (2009). For the current analysis, the variable was therefore dichotomous—with adequate or inadequate fracture reduction.

Figure 3.

A. Modified Garden’s alignment index, anterior-posterior angle through capital trabeculae and medial femoral cortex. B. Modified Garden’s alignment index, axial angulation of the femoral head center and midline of the femoral neck.

Predictors of failure

2 possible predictors of failure were chosen from the questionnaire. For comorbidity, alcohol was considered to be the best variable; Duckworth et al. (2011) showed that it is an important risk factor for fixation failure in patients less than 60 years of age. We defined excessive alcohol consumption as greater than 21 units per week for men and greater than 14 units per week for women (1 unit = 15 mL or 12 g of alcohol). Walking disability is a risk factor for not returning home (Vochteloo et al. 2012), and it was assessed from a yes/no question regarding the use of walking aids.

Primary covariate was BMD compared to failure of IF from date of surgery to date of extraction from the Danish National Registry of Patients (November 9, 2010), reoperation, or death (whatever came first). Secondary covariates were possible predictors of failure: displacement of fracture, implant positioning, quality of reduction, age, sex, comorbidity, and walking disability.

Statistics

In order to minimize mass significance, the 2 most likely predictors of failure from the questionnaire were chosen for the analysis. Data were set as survival data, and group comparison with log rank tests and Kaplan-Meier graphs showed major variation in relation to fracture displacement. In order to establish that there was a potentially minor influence of low BMD and the other covariates, the Cox regression was stratified on fracture displacement. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated statistically (goodness of fit) and graphically using log(-log) Kaplan-Meier survival plot against survival time. One variable (implant positioning) did not satisfy the proportional hazards assumption and was used as a time-dependent variable (multiplied by the logarithm of analysis time) as described by Kleinbaum and Klein (2011). The extended (time-dependent implant positioning) stratified (fracture displacement) Cox regression model was also adjusted for age, sex, quality of reduction, alcohol, and walking disability. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined. The statistical software program STATA 11 was used.

Results

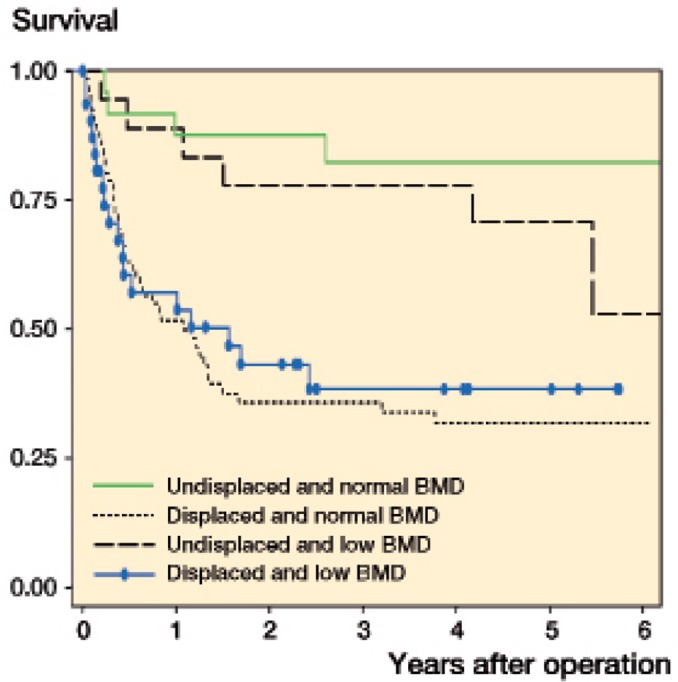

The failure rate was 22% (CI: 12–39) for undisplaced fractures and 66% (CI: 56–76) for displaced fractures after 2 years. The overall failure rate from fracture displacement and total hip BMD level was similar irrespective of whether or not the patient had low BMD (Figure 4). The median time to failure was 158 days (IQR: 79–425) and the median time from the DXA scan to failure was 86 days (IQR: 4–280).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier hip survival according to fracture displacement and total hip BMD.

The preliminary log rank tests stratified for fracture displacement showed statistical significance only for implant positioning. The extended Cox regression was stratified on fracture displacement (so no results are shown for fracture displacement), and showed the same result, with no association between low hip BMD and failure (Table 2). There were no statistically significant associations between any covariate and failure, apart from implant positioning (HR = 66, CI: 4–1240). The analysis was also done with femoral neck BMD instead of total hip BMD and gave the same result (HR = 1.1, CI: 0.7–1.9). A subgroup analysis of the undisplaced fractures revealed no statistically significant association between low BMD and failure risk in the Cox regression analysis (HR = 6.2, CI: 0.5–73) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Results from the extended stratified Cox regression a

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low total hip BMD | 0.8 | 0.5–1.5 | 0.5 |

| Implant positioning | 66 | 4–1,240 | 0.005 |

| Quality of reduction | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 | 0.4 |

| Sex | 1.5 | 0.8–2.9 | 0.2 |

| Age | 1.6 | 0.8–3.3 | 0.2 |

| Alcohol | 1.6 | 0.6–4.3 | 0.4 |

| Walking disability | 1.0 | 0.6–1.8 | 0.9 |

a n = 115 due to lack of one or more covariates.

Table 3.

Results from a subgroup-based Cox regression analysis of the undisplaced fractures a

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low total hip BMD | 6 | 0.5–74 | 0.1 |

| Implant positioning | 22 | 2–292 | 0.02 |

| Sex | 6 | 0.3–112 | 0.2 |

| Age | 0.3 | 0.1–2.4 | 0.3 |

| Alcohol | 0.5 | 0.1–3.8 | 0.5 |

| Walking disability | 0.1 | 0.1–1.0 | 0.05 |

a n = 37 due to lack of one or more covariates.

Discussion

We found no association between low hip BMD and fixation failure. As in previous studies, the most important predictors of failure were fracture displacement and implant positioning. The lack of effect of other known predictors (age, sex, and quality of reduction) of fixation failure may be due to the effect of sample size; Parker et al. (2007) showed that a large sample size is needed to see an effect of gender on fixation failure.

To our knowledge, only 3 other clinical studies have investigated the effect of BMD on failure of internal-fixed femoral neck fractures. Karlsson et al. (1996) investigated changes of BMD in 47 femoral neck fractures, and as a secondary outcome they found no association between BMD and late segmental collapse or pseudoarthrosis. However, no information was given regarding displacement, implant positioning, or quality of reduction. Heetveld et al. (2005) DXA-scanned displaced femoral neck fracture patients and they found similar BMD in patients with fixation failure and in the group without failure. The study had data on age, sex, implant positioning, and quality of reduction but there was no adjustment for them. The only study with all known potential confounders in their analysis was that of Spangler et al. (2001) who found that patients with a registered ICD-9-CM code for osteoporosis had a hazard ratio of 8 for revision surgery. However, they may have underestimated the prevalence of osteoporosis in their patients (9%); other studies have shown osteoporosis percentages as high as 82% in this patient group (McLellan et al. 2003). There was also a possible bias in the study by Spangler et al. (2001) due to the fact that the osteoporosis diagnoses could have been based on low spine BMD.

Heetveld et al. (2005) reported preoperative BMD measurements whereas we used BMD measurements taken 80 days (IQR: 60–101) after surgery. It is difficult to conclude which approach is best, because neither study showed a definite link between failure and BMD value, and our study had a median time from the DXA scan to failure of 86 days (IQR: 4–280). Karlsson et al. (1996) performed DXA scans immediately after the fracture, and at 4 months and 12 months, but they did not have information regarding other factors which may predict failure. When comparing the results in the literature with our findings, factors that influence the hip BMD measurement must also be taken into account. BMD of the hip is not constant, and declines in the elderly population by approximately 0.5% per year (Cauley et al. 2005). In patients with a hip fracture, the decline 1 year after the fracture is greater and hip BMD ranges from 2% to 7% (Karlsson et al. 1996, Fox et al. 2000). Such a decline in hip BMD has also been seen in patients with tibial fractures (Van der Wiel et al. 1994) and Achilles rupture (Therbo et al. 2003), and is probably due to inactivity. Other factors such as exercise and the use of bone-preserving drugs can also influence the decline in hip BMD (Anastasilakis et al. 2009, Howe et al. 2011). There is also a side-dependent difference when measuring total hip BMD which has been estimated to 6% (Schwarz et al. 2011).

In hip fracture patients, only 1 study has investigated the difference in BMD between the injured side and the uninjured side (Karlsson et al. 1996). For femoral neck fracture patients, there was a difference of 20–29% after 4 months and of 1–6% after 12 months. The reliability of these measurements must be questioned, however, because the regions measured were small and the measured values had high standard deviations. Another study measured the effect after removal of an intramedullary nail and showed that the difference was only 6% for trochanter BMD (Kroger et al. 2002). Even though there might be a difference between the injured hip and the uninjured hip, it is probably not as large as measured by Karlsson et al. (1996).

The present study had some limitations. The CIs of our results were generally large, and the sample size should therefore have been greater. Secondly, there was a selection bias since patients with severe comorbidity and dementia were excluded and the median time to the DXA scan was 80 days. The 30-day mortality was therefore 0% in this cohort and 6% after 1 year. At the same time, this bias is also a strength, because we had very few censored data due to death. Finally, there could have been a measuring bias concerning implant positioning and quality of reduction since we modified both measurements slightly and did not validate them. We do not, however, believe that the alterations influenced the validity of the scoring system.

There were also strengths; this was a population-based study with a well-defined cohort and external validity could be assessed easily. Secondly, low bone quality was measured with a DXA scanner—the gold standard. Thirdly, the department had a strict guideline regarding the use of IF for all femoral neck fractures. Finally, extraction of data from the Danish National Registry of Patients allowed us to find 2 additional patients with failure, which would not normally be possible.

Low bone BMD may be a factor in IF failure. Although not statistically significant, the subgroup analysis for undisplaced fractures (Table 3) showed a hazard ratio of 6 for low BMD as compared to 0.8 for the whole group (Table 2). For undisplaced femoral neck fractures, there should be a normal blood supply and good bone contact between the bone fragments. Compared to displaced fractures, the major reason for failure might lie in the stability. Osteoporosis appears to affect the anchorage of screws (Sjostedt et al. 1994, Bonnaire et al. 2005) and could therefore be a reason for lower stability in the undisplaced fracture, and hence failure.

In conclusion, we found that low hip BMD is not statistically significantly associated with fixation failure (HR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.46–1.47; p < 0.506) in femoral neck fracture patients treated with IF.

Acknowledgments

BV: conception and design, acquisition of data, radiographic measurements, drafting of article, and analysis and interpretation of results. JR: conception and design, acquisition of data, and revision of article. JL: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of results, and revision of article. OO and SO: conception and design, and revision of article.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Anastasilakis AD, Toulis KA, Goulis DG, Polyzos SA, Delaroudis S, Giomisi A, et al. Efficacy and safety of denosumab in postmenopausal women with osteopenia or osteoporosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis . Horm Metab Res. 2009;41:10, 721–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnaire F, Zenker H, Lill C, Weber AT, Linke B. Treatment strategies for proximal femur fractures in osteoporotic patients . Osteoporos Int (Suppl 2) 2005;16:S93–S102. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley JA, Lui LY, Stone KL, Hillier TA, Zmuda JM, Hochberg M, et al. Longitudinal study of changes in hip bone mineral density in Caucasian and African-American women . J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2, 183–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AD, Bennet SJ, Aderinto J, Keating JF. Fixation of intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck in young patients: risk factors for failure . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93:6, 811–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B6.26432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox KM, Magaziner J, Hawkes WG, Yu-Yahiro J, Hebel JR, Zimmerman SI, et al. Loss of bone density and lean body mass after hip fracture . Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:1, 31–5. doi: 10.1007/s001980050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen PA. Osteosynthesis of displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A comparison between Smith-Petersen Osteosynthesis and sliding-nail-plate osteosynthesis—a radiological study . Acta Orthop Scand. 1979;50:4, 443–9. doi: 10.3109/17453677908989788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoudis P, Tzioupis C, Almalki T, Buckley R. Fracture healing in osteoporotic fractures: is it really different? A basic science perspective . Injury (Suppl 1) 2007;38:S90–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjertsen JE, Fevang JM, Matre K, Vinje T, Engesaeter LB. Clinical outcome after undisplaced femoral neck fractures. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:3, 268–74. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.588857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heetveld MJ, Raaymakers EL, van Eck-Smit BL, van Walsum AD, Luitse JS. Internal fixation for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. Does bone density affect clinical outcome? . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005;87:3, 367–73. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.87b3.15715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heetveld MJ, Raaymakers EL, Luitse JS, Gouma DJ. Rating of internal fixation and clinical outcome in displaced femoral neck fractures: a prospective multicenter study . Clin Orthop. 2007;454:207–13. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238867.15228.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe TE, Shea B, Dawson LJ, Downie F, Murray A, Ross C, et al. Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. CD000333. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ, 3rd,, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis . Bone. 2008;42:3, 467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M, Nilsson JA, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Johnell O, Obrant KJ. Changes of bone mineral mass and soft tissue composition after hip fracture . Bone. 1996;18:1, 19–22. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival analysis: A self-learning text. Springer. 2011. Third ed.

- Kroger H, Kettunen J, Bowditch M, Joukainen J, Suomalainen O, Alhava E. Bone mineral density after the removal of intramedullary nails: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study . J Orthop Sci. 2002;7:3, 325–30. doi: 10.1007/s007760200055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults . Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:5, 468–89. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C. The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture . Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:12, 1028–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1507-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm H, Gosvig K, Krasheninnikoff M, Jacobsen S, Gebuhr P. A new measurement for posterior tilt predicts reoperation in undisplaced femoral neck fractures: 113 consecutive patients treated by internal fixation and followed for 1 year . Acta Orthop. 2009;80:3, 303–7. doi: 10.3109/17453670902967281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ. Garden grading of intracapsular fractures: meaningful or misleading? . Injury. 1993;24:4, 241–2. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(93)90177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Gurusamy K. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty for intracapsular proximal femoral fractures in adults . Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001708.pub2. CD001708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Raghavan R, Gurusamy K. Incidence of fracture-healing complications after femoral neck fractures . Clin Orthop. 2007;458:175–9. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180325a42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogmark C, Johnell O. Primary arthroplasty is better than internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized studies with 2,289 patients . Acta Orthop. 2006;77:3, 359–67. doi: 10.1080/17453670610046262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryg J. Department of Endocrinology, Odense University Hospital. Institute of Clinical Research, Faculty of Health Science; University of Southern Denmark: 2009. The frail hip—A study on the risk of second hip fracture, prevalence of osteoporosis, and adherence to treatment in patients with recent hip fracture. PhD Thesis; p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- Schep NW, Heintjes RJ, Martens EP, van Dortmont LM, van Vugt AB. Retrospective analysis of factors influencing the operative result after percutaneous osteosynthesis of intracapsular femoral neck fractures . Injury. 2004;35:10, 1003–9. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz P, Jørgensen NR, Jensen LT, Vestergaard P. Bone mineral density difference between right and left hip during ageing. Eur Geriatr Med. 2011;2:2, 82–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sjostedt A, Zetterberg C, Hansson T, Hult E, Ekstrom L. Bone mineral content and fixation strength of femoral neck fractures. A cadaver study . Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65:2, 161–5. doi: 10.3109/17453679408995426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler L, Cummings P, Tencer AF, Mueller BA, Mock C. Biomechanical factors and failure of transcervical hip fracture repair . Injury. 2001;32:3, 223–8. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)00186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therbo M, Petersen MM, Nielsen PK, Lund B. Loss of bone mineral of the hip and proximal tibia following rupture of the Achilles tendon . Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13:3, 194–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.20205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Wiel HE, Lips P, Nauta J, Patka P, Haarman HJ, Teule GJ. Loss of bone in the proximal part of the femur following unstable fractures of the leg. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1994;76:2, 230–6. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Embden D, Rhemrev SJ, Genelin F, Meylaerts SA, Roukema GR. The reliability of a simplified Garden classification for intracapsular hip fractures . Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:4, 405–8. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vochteloo AJ, van Vliet-Koppert ST, Maier AB, Tuinebreijer WE, Roling ML, de Vries MR, et al. Risk factors for failure to return to the pre-fracture place of residence after hip fracture: a prospective longitudinal study of 444 patients . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:6, 823–30. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1469-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]