Abstract

In the context of oncology, dynamic PET imaging coupled with standard graphical linear analysis has been previously employed to enable quantitative estimation of tracer kinetic parameters of physiological interest at the voxel level, thus, enabling quantitative PET parametric imaging. However, dynamic PET acquisition protocols have been confined to the limited axial field-of-view (~15–20cm) of a single bed position and have not been translated to the whole-body clinical imaging domain. On the contrary, standardized uptake value (SUV) PET imaging, considered as the routine approach in clinical oncology, commonly involves multi-bed acquisitions, but is performed statically, thus not allowing for dynamic tracking of the tracer distribution. Here, we pursue a transition to dynamic whole body PET parametric imaging, by presenting, within a unified framework, clinically feasible multi-bed dynamic PET acquisition protocols and parametric imaging methods. In a companion study, we presented a novel clinically feasible dynamic (4D) multi-bed PET acquisition protocol as well as the concept of whole body PET parametric imaging employing Patlak ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to estimate the quantitative parameters of tracer uptake rate Ki and total blood distribution volume V. In the present study, we propose an advanced hybrid linear regression framework, driven by Patlak kinetic voxel correlations, to achieve superior trade-off between contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) and mean squared error (MSE) than provided by OLS for the final Ki parametric images, enabling task-based performance optimization. Overall, whether the observer's task is to detect a tumor or quantitatively assess treatment response, the proposed statistical estimation framework can be adapted to satisfy the specific task performance criteria, by adjusting the Patlak correlation-coefficient (WR) reference value. The multi-bed dynamic acquisition protocol, as optimized in the preceding companion study, was employed along with extensive Monte Carlo simulations and an initial clinical FDG patient dataset to validate and demonstrate the potential of the proposed statistical estimation methods. Both simulated and clinical results suggest that hybrid regression in the context of whole-body Patlak Ki imaging considerably reduces MSE without compromising high CNR. Alternatively, for a given CNR, hybrid regression enables larger reductions than OLS in the number of dynamic frames per bed, allowing for even shorter acquisitions of ~30min, thus further contributing to the clinical adoption of the proposed framework. Compared to the SUV approach, whole body parametric imaging can provide better tumor quantification, and can act as a complement to SUV, for the task of tumor detection.

1. Introduction

Quantitative PET imaging of parameters of physiological interest is critical for assessment of treatment response in clinical oncology (Castell and Cook 2008). The standardized uptake value (SUV), a surrogate of metabolic activity, has been established as the standard clinical approach in oncology to image the PET tracer uptake, such as 18F-deoxyglucose (FDG), over multiple bed positions across the whole body (Wahl and Buchanan 2002, Facey et al 2007, Castell and Cook 2008). SUV imaging commonly involves static multi-bed acquisitions (one for each bed) usually performed after one hour post injection when the tracer uptake in the tissues of interest is adequate (Dahlbom et al 1992, Kubota et al 2001, Hustinx et al 2002, Townsend 2008). As a result, SUV protocols are relatively simple for easy clinical adoption as they do not require tracking of the tracer activity distribution in the blood plasma (input function) and the tissues (tissue time activity curves - TACs) during the first hour after injection. However, SUV values not only depend on plasma activity but also on the actual time of scan at each bed, which may differ between PET clinics or protocols. Therefore the SUV is a semi-quantitative metric for the estimation of glucose metabolic rate or the glucose influx rate constant Ki (Leskinen-Kallio et al 1992, Hamberg et al 1994, Keyes 1995, Weber et al 1999, Huang 2000, Adams et al 2010).

In the past, alternative estimation methods have been proposed to provide more quantitative estimates of Ki by accounting for the input function while retaining the simplicity of acquiring a single scan per bed. The tracer retention method by Hunter et al (1996) recommends the division of the measured activity at a given time (usually 45min to 1hr post-injection) with the total integral of the input function to that time. However, this approach assumes negligible presence of non-metabolized uptake, degrading quantitative accuracy for earlier scan times and/or for less FDG-avid tumors, and also leading to time-dependence of the metric. In addition, the autoradiographic method, first introduced by Sokoloff et al (1977) and later expanded for human brain FDG studied by Huang et al (1980), proposed the estimation of Ki again from a single static scan per bed and a complete input function, employing a two-tissue kinetic compartment model and requiring the usage of pre-determined set of kinetic parameter values. The new estimates of Ki are considered more quantitative as they exhibit better correlation with Ki estimates as derived from a dynamic study and using a kinetic two-tissue compartmental model; i.e. the Patlak method (Burger et al 2011). However, as we further explain in our companion study (Karakatsanis et al 2013b) this correlation is also time-dependent, while both methods make strong assumptions which can lead to significant quantification errors particularly in low activity levels.

On the contrary, dynamic PET imaging acquires measurements of the tracer activity concentration in the blood plasma (input function) and the tissue (time activity curves, TACs) across multiple dynamic frames and in conjunction with tracer kinetic modeling allows for time-independent and, thus, more quantitative estimation of parameters of physiological interest, including Ki and metabolic rate of glucose (Wong and Hicks 1994, Sadato et al 1998, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss et al 2001). Furthermore, fast linear graphical analysis methods (Patlak et al 1983, Patlak and Blasberg 1985, Zhou et al 2010) can be employed to utilize the 4D acquired data and efficiently estimate, at the voxel level, tracer kinetic macro-parameters, ultimately providing quantitative PET parametric images. However, parametric imaging has been confined to the small axial field-of-view (FOV) of single-bed (~15–20cm) acquisitions, therefore, limiting its current applications scope to the research setting, without translating to the clinical whole-body PET domain.

Overall, in the current work and a companion study (Karakatsanis et al 2013b), we pursue a transition from single- to multi-bed PET parametric imaging by presenting a novel imaging framework equipped with a clinically feasible and optimized multi-bed dynamic acquisition protocol as well as with enhanced indirect parameter estimation methods to enable task-based imaging capabilities. In this study, particularly, by focusing on the specifics of parameter estimation, our aim is to provide a more clinically adaptable imaging solution capable of achieving enhanced trade-off between contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) (related to more reliable tumor detection) and the mean squared error (MSE) in the parameter voxel estimates (related to quantitative assessment of treatment response).

In the companion study, we developed an optimal 4D multi-bed PET data acquisition protocol and validated both through simulation and patient FDG datasets to demonstrate clinical feasibility. Patlak linear graphical analysis modeling was employed at the voxel level, coupled with input function estimation from the images, to estimate by ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, two kinetic macro-parameters: the tracer uptake rate Ki (slope) and the total blood distribution volume V (intercept) (Patlak et al 1983, Patlak and Blasberg 1985, Zhou et al 2010). Results demonstrated superior CNR for Ki images in tumor regions with notable background concentration, such as the liver, where SUV performed poorly.

Ordinary least squares regression has been the standard parameter estimation method for Patlak imaging in PET and is the method with the minimum variance among all linear unbiased estimation methods. However, as we demonstrate in section 3.1, under certain statistical conditions, which may arise in highly noisy PET data, the variance of the OLS estimates may increase significantly, resulting in higher MSE. Ridge regression, a biased estimation method originally introduced by Hoerl and Kennard (1970), has been proposed in the past as a promising ROI-based (O'Sullivan et al 1999, Byrtek et al 2005) and voxel-wise (Zhou et al 2001, 2003) parameter estimation method, in the context of dynamic brain PET imaging, to reduce the variance and the MSE in the estimates at the expense of a small bias.

In the current study we move beyond standard OLS regression and evaluate an extended set of advanced ridge regression (RR) schemes, in the context of whole-body PET parametric imaging. This is an important direction of research in the present context due to the relatively high noise levels in the voxel estimates induced by (i) the high statistical noise present in the short dynamic PET frames (45sec) and (ii) the small number of dynamic frames per bed. Subsequently we utilize the quantitative metric of Patlak correlation-coefficient at each voxel to develop a hybrid regression method which selectively combines OLS and RR to achieve superior trade-off between the CNR and the MSE in the Ki images.

2. Dynamic whole-body PET imaging

2.1. Patlak quantitative imaging

As elaborated in the companion study (Karakatsanis et al 2013b), the SUV metric, routinely employed for the quantification of the tracer (e.g. FDG) uptake in clinical PET, can be considered as a semi-quantitative surrogate of metabolic activity and may result in erroneous estimation of the metabolic rate of glucose in clinical FDG studies (Sadato et al 1998, Zasadny and Wahl 1993, Kim et al 1994, Hamberg et al 1994, Keyes 1994, Kim and Gupta 1996, Weber et al 1999, Huang 2000, Adams et al 2010). In fact SUV is only related to the amount of injected dose (Dose) and the lean body mass (LBM):

| (1) |

where, C(t) is the measured tracer concentration, decay corrected with respect to the injection time.

Dynamic PET imaging, on the other hand, allows for acquisition of the tracer activity concentration at different time frames. Subsequently, fast linear graphical analysis methods, such as Patlak, can utilize the 4D measurements to provide quantitative parametric images. Patlak method assumes for the underlying tracer kinetics a 2-tissue-compartment kinetic model (figure 1) with an irreversible metabolic compartment (k4~0), which is the standard kinetic model for FDG tracer.

Figure 1.

A graph for the compartment model of 18F-FDG tracer uptake. Cp(t), C1(t) and C2(t) are the tracer concentration in plasma, free (reversible) and metabolized (irreversible, k4 ~ 0) compartments respectively.

According to Patlak graphical analysis and assuming the kinetic model of figure 1, the tracer metabolic rate Ki and the total blood distribution volume V are estimated by applying linear regression methods to the Patlak model defined in equation 2, for t ≥ t*(t* is the time after which relative equilibrium is attained between the vascular space and reversible tissue compartment) (Patlak et al 1983, Patlak and Blasberg 1985):

| (2) |

2.2. Design of 4D multi-bed acquisition

One of the major challenges associated with whole body PET parametric imaging is the multi-bed acquisition of dynamic PET data. In our companion study we optimized a clinically feasible multi-bed acquisition protocol and applied it on a GE Discovery RX LYSO PET/CT scanner, located at Johns Hopkins PET center.

The proposed protocol has a total length of 48min and is implemented in two subsequent time phases (Karakatsanis et al 2013b):

an initial 6-min single-bed dynamic scan over the cardiac region comprised of 24 frames with the following time sequence: (12 frames) × (10sec) + (12 frames) × (20sec), in order to later extract, the early tracer dynamics in the blood plasma, followed by

a sequence of 6 whole-body scans (passes), each lasting approximately 6min and comprised of seven beds, each scanned for 45sec, to capture the late dynamics of the tracer in both the blood plasma and the tissues.

The input function was derived from the 24 dynamic cardiac frames of the early phase and the 6 subsequent passes over the cardiac bed of the later phase. A left-ventricle (LV) ROI was drawn in each frame and the mean values were extracted. Later, the input function was estimated at the remaining dynamic frames by linear interpolation. In figure 2, the acquisition frame sequence of the second phase is presented. Further details and discussions about the implementation challenges of the protocol as well as a description of the optimization process can be found in the companion study (Karakatsanis et al 2013b).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the acquisition time sequence for the later 6 whole-body passes (second phase of the protocol). Each row describes the acquisition of a particular whole-body pass over time (only 3 of the 6 passes are shown). The time is running row-wise. Note that every pass consists of 7 bed frames. Each column corresponds to one bed position. The earlier dynamic scan is performed on bed 3, for the first 6min after injection, and is not shown here.

3. Statistical parameter estimation methods

The 4D acquisition over multiple beds in a clinically feasible time is only one aspect of the presented whole body PET parametric imaging framework. An equally important task is the efficient task-based utilization of the acquired 4D data to provide whole body parametric images of clinical value. For this purpose, in this study we focus on the development and evaluation of advanced linear regression methods, which utilize the 4D acquired data and their Patlak correlation information to perform task-based parameter estimation at the voxel level.

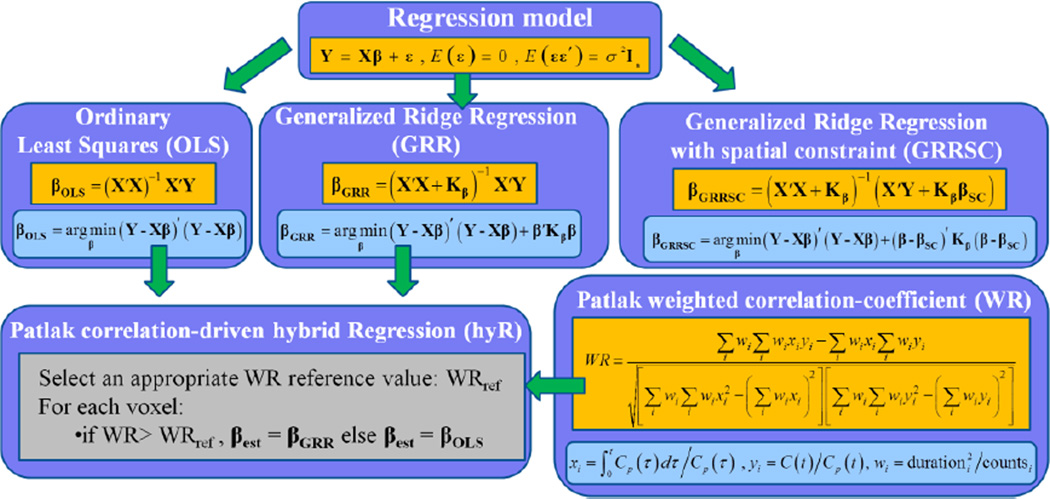

Initially, the standard Patlak linear regression model is introduced followed by a description of the OLS regression method and its limitations (section 3.1). Then, a set of generalized and simplified RR methods are presented (section 3.2). Subsequently, the concept of Patlak weighted correlation coefficient, as calculated for each voxel TAC, is defined (section 3.3) followed by the presentation of our proposed hybrid regression algorithm (section 3.4). Finally, a set of spatially constrained ridge regression estimation methods are included and compared against the previous methods (section 3.5). The proposed parameter estimation methods of this section are summarized in figure 3.

Figure 3.

An overview of the Patlak linear regression model and the relevant parameter estimation methods examined in this study. Hybrid regression is implemented by efficiently selecting between OLS and GRR regression techniques based on weighted Patlak correlation-coefficient WR at each voxel.

3.1. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS)

Let us formulate Patlak linear eq. (2) in the bi-linear form:

| (3) |

By considering (2) and (3), we can arrive at the standard model for linear regression:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where X is an n×m independent variable matrix, n denotes the number of dynamic frames, each acquired at time ti, i =1,…n at each bed position and m is the number of unknown regression parameters, Y is an n×1 vector of known predictor variables, β is a m×1 vector of unknown regression parameters, ε is an n×1 vector of noise following the normal distribution, σ2 is the error variance and In is an n×n identity matrix. In the present context, m=2 (the Patlak slope and intercept parameters), and according to the acquisition protocol described in section 2, n = 6.

The conventional estimator for regression parameter vector β is the OLS estimator vector βOLS, which minimizes the residual sum of squares RSS or φ, given by:

| (6) |

| (7) |

The OLS estimator is the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE), because its expected value is equal to the true regression parameter vector β, and achieves minimum variance among all linear unbiased estimators when ε is normally distributed. Hoerl and Kennard (1970a, b) emphasized on the mean squared error (MSE) of the OLS estimates. They demonstrated a substantial increase in the MSE, with increasing multi-collinearity in the regression problem, i.e. when the columns or rows of X′X become increasingly correlated (see Appendix A) (Marquardt and Snee 1975). Since OLS estimates are unbiased, increase of MSE (MSE=Variance+Bias2) is attributed to higher variance.

In the following section we present ridge regression, a biased estimation method, to reduce the variance in the voxel estimates of parametric (Ki) images. Our aim is to efficiently address the outlined limitations of OLS in an effort to ultimately reduce the large MSE often associated with Ki images.

3.2. Ridge Regression

Hoerl and Kennard first introduced ridge regression (RR) to circumvent the problem of potentially large MSE in OLS estimates. They proposed adding relatively small positive quantities, the ridge parameters, to the diagonal elements of the X′X matrix. Simplified ridge regression (SRR) involves a single ridge parameter h added to all m diagonal elements. On the contrary, if independent ridge parameters hi are added to each of the diagonal elements of X′X, the generalized ridge regression (GRR) is applied. The ridge regression solutions for SRR and GRR schemes, as well as the objective functions they minimize, are presented in Table I (Hoerl and Kennard 1970a, b).

Table I.

Ridge Regression Solutions and Minimization Problems

| Optimal solutions | Minimization of objective function |

|---|---|

| (8) | βSRR = (X′X + hIm)−1 X′Y, h > 0 (10) |

| (9) | βGRR = (X′X + Hβ)−1 X′Y (11) |

The subscript β in the notation of the mxm ridge parameter matrix Hβ suggests derivation of the optimal ridge parameters from the original space of regression parameters β. Later, a methodology is presented to optimize the ridge parameters in GRR from a transformed space. In the case of SRR, such transformation is not required.

By combining (6) with (10) and (11), it is obvious that ridge regression estimators are linear transforms of the OLS estimators.

| (12) |

| (13) |

Note that when the ridge parameters are zero, βSRR = βGRR = βOLS. Hoerl and Kennard (1970a, b) showed that βSRR has shorter squared length than βOLS for h ≠ 0, i.e.

| (14) |

The MSE or, equivalently, the expected squared distance of βSRR from the true parameters β is:

| (15) |

The first term, , expresses the total variance of the elements of βSRR, while the second term, , can be considered as the squared bias introduced when βSRR is used instead of βOLS. Ridge parameter h is a free parameter and can be optimized to minimize MSE. Total variance decreases, while squared bias increases with h. Hoerl and Kennard (1970a, b) have demonstrated that there exists h > 0, such that:

| (16) |

Thus, there exist admissible values of ridge parameters h > 0 such that the MSE of βSRR is smaller than the MSE of the OLS estimator βOLS. The same conclusions holds for the GRR scheme as well.

In Appendix B we present transformation of the regression problem to an orthogonal space where new parameters α are now to be estimated. Furthermore, we demonstrate the relationship between the calculated ridge parameters in the original space, Hβ, and the transformed space Hα. Moreover, we derive the theoretical MSE for ridge regression and show how the set of ridge parameters are optimized, utilizing the transformed parameters, to achieve minimum MSE. A collection of methods, as obtained from the literature, to optimize the ridge parameters are summarized at the end of section 3.

3.3. Kinetic correlations based clustering

The weighted Patlak correlation coefficient (WR) of the kinetics at each voxel is calculated in order to quantify the goodness of fit of the tracer kinetics to the Patlak model. In reference to (2), xi and yi, i = 1,…, n = 6 are set as follows:

| (17) |

We can then calculate the kinetic WR at each voxel from the following equation (Zasadny and Wahl 1996):

| (18) |

The derived kinetic correlation image is utilized to group all voxels into two clusters by comparing their associated WR value with a user-defined WR reference value. Thus, two clusters of image voxels are shaped, each characterized by a certain degree of Patlak correlation: the high (hWR) and low (lWR) kinetic correlation clusters.

Voxels belonging to the hWR cluster are more likely to be associated with high uptake rate regions, such as tumors and the myocardium, or, overall, regions with sufficient count statistics and smooth TACs. On the contrary, the lWR cluster is expected to include voxels with insufficient Patlak correlation corresponding to noisy TACs due to low count statistics, such as tumor background regions.

The performance of the WR based hybrid regression method, presented in the following section, relies on the selection of an “appropriate” WR reference/threshold value to best match the two produced clusters with the statistical properties described above. However, each oncology patient may be characterized by tumors of different contrast environment and thus different statistical properties. By definition, WR can accept values between −1 and +1. Thus, we propose a range of WR reference values [0.6, 0.95] to cover a range of possible correlation coefficients that may be associated with common tumor contrast environments. Later, a quantitative criteria can be selected to determine which specific reference value achieves best performance. The selection of the quantitative metric can be task-dependent, thus, potentially allowing for task-based optimization, as we discuss in the next section.

3.4 Hybrid regression

In the companion study (Karakatsanis et al 2013b) we presented a WR-driven method, also applied here, wherein WR-based thresholding was performed on OLS parametric images. By contrast, here we propose hybridizing the estimation process based on the WR reference value. Thus, we selectively apply OLS estimation, followed by post smoothing (Gaussian, FWHM=3mm), to the lWR cluster, while, for the hWR cluster, ridge regression without post smoothing is employed (as justified next).

In the lWR cluster the reconstructed PET images exhibit positive bias (overestimation), partially induced by the non-negativity constraint of the OSEM algorithm in regions with low count statistics (Rahmim et al 2005, Walker et al 2011). Overestimation in individual dynamic frames will likely bias Ki in parametric images. In addition, the low count statistics induce higher noise levels in the parameter estimates. By comparing RR and OLS parametric images, we have systematically observed that although the estimator vector of the two Patlak parameter estimates (slope and intercept) in OLS is larger in total length, the vector element corresponding to the slope is systematically smaller in the background regions (lWR cluster). As a result, OLS is associated with smaller positive bias than RR in the lWR cluster. On the other hand, in tumor regions (hWR cluster) RR is observed to induce lower variance and lower total MSE at the expense of a small bias relative to OLS.

Therefore, for the lWR cluster we propose applying OLS estimation to limit the positive bias, followed by post-smoothing to reduce the noise in the background. On the contrary, in the hWR cluster, where the quality of the kinetic statistics is sufficient and quantification is more crucial, we apply generalized ridge regression without post-smoothing to achieve lower MSE in the estimates of the tumor regions. The flow chart of the proposed hybrid regression algorithm is illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 4.

A flow chart describing the proposed algorithm of hybrid regression. Initially the kinetic correlation-coefficient WR image is calculated and WR clustering is performed. Subsequently, the WR at each voxel is compared against a user-defined threshold and, if it is higher, GRR is applied at the particular voxel TAC, otherwise OLS followed by post-smoothing. The result, hybrid regression is compared against standalone smoothed OLS or GRR. In this flow-chart WR reference was 0.85.

Hybrid regression utilizes the available kinetic correlation information to selectively apply parameter estimation methods to appropriate contrast environments in order to ultimately achieve a better trade-off between diagnostic value (CNR) and quantification (MSE) in the parametric images. As we discussed in the previous section, we propose examining an initial range of WR reference values [0.6 0.95] and then choose the value that produces images with the best quantitative performance. Depending on the observer task, the WR reference value may be selected to emphasize maximized CNR, for enhanced diagnosis, or minimized MSE, for better quantification. Thus, the free nature of the WR reference value enables task-oriented performance optimization through hybrid regression.

3.5. Ridge Regression with spatial constraint

In the current section we present an alternative ridge regression scheme equipped with a spatial constraint (RRSC) in order to limit the additional bias induced by regular ridge regression RR (Zhou et al 2003). Let us consider the two-dimensional parameter space β = (β1, β2) = (Ki,V). In the case of RR, the larger the values of the ridge parameters hi employed, the closest the end point of the RR estimate vector is to the origin β0 = (0,0) and the shortest its length. Essentially RR constraints the estimates towards the origin. On the contrary, RRSC constraints the estimates towards a prior estimate βSC, the spatial constraint. The objective functions and the minimizing solutions are presented in Table II. The equivalent RRSC objective functions and optimal solutions in the transformed parameter space α can easily be derived, as in the case of RR. Also, βGRRSC can be expressed with respect to Hα, as follows:

| (23) |

Table II.

Ridge Regression With Spatial Constraint Solutions and Minimization Problems

| Optimal solutions | Minimization of objective function |

|---|---|

| (19) | βSRRSC = (X′X + hIm)−1 (X′Y + hβSC), h > 0 (21) |

| (20) | βGRRSC = (X′X + Hβ)−1 (X′Y + HββSC) (22) |

In appendix C we demonstrate that MSEGRRSC < MSEGRR provided our spatial constraint is a “good” estimate of the unknown true parameters. In addition, we show that both MSEGRR and MSEGRRSC, when calculated after optimizing the ridge parameters, are theoretically smaller than MSEOLS, suggesting an advantage of ridge regression over OLS in terms of MSE. A collection of methods to estimate the optimal ridge parameters from the actual data is presented in the right column of Table III.

Table III.

Optimization of Ridge Parameters in RR and RRSC Schemes

| Ridge Regression (RR) | Ridge Regression with spatial constraint (RRSC) |

|---|---|

|

(theoretical) (Hoerl and Kennard 1970a and b) |

(theoretical) (Zhou et al 2003) |

|

(Hoerl and Kennard 1970a and b) |

(Zhou et al 2013, Karakatsanis et al 2012b, 2013b) |

|

(Hoerl and Kennard 1970a and b) |

(Karakatsanis et al 2012b, 2013b) |

|

(Hoerl et al 1975) |

(Karakatsanis et al 2012b, 2013b) |

|

(Lawless and Wang 1976) |

(Karakatsanis et al 2012b, 2013b) |

|

(Kibria et al 2003) |

(Karakatsanis et al 2012b, 2013b) |

|

(Karakatsanis et al 2012b, 2013b) |

|

|

where GGCV_SRR (h) = X(X′X + nhIm)−1 X′ (Golub et al 1979) |

where GGCV_SRRSC(h) = X(X′X + nhIm)−1 (X′ + nhImβSC) (Karakatsanis et al 2012b, 2013b) |

In our study we construct our prior image βSC by applying kinetic correlation driven post smoothing (Gaussian, FWHM=3mm) on the initial OLS estimated image βOLS, using WR=0.85 as a reference threshold. We also implemented a mixed GRRSC_GRR regression scheme, which utilizes the GRR optimal ridge parameters (B15) within the GRRSC framework (22) to reduce the penalty term in the objective function (20) and avoid the strong enforcement of potentially “bad priors” (appendix C).

3.6. Optimization of the ridge parameters

In previous sections we demonstrated that ridge parameters are free and can be used to minimize the theoretical MSE. In the left column of table III, we summarize the methods to optimize the ridge parameters in theory and from data, as proposed in the literature (Hoerl and Kennard 1970a and b, Allen 1971, Lawless and Wang 1976, Golub et al 1979, Kibria 2003). Also, in the right column we propose an equivalent collection of methods for RRSC. The parameters αi, i =1,2 and the variance σ2 are defined in appendices B and C.

4. Simulation Studies

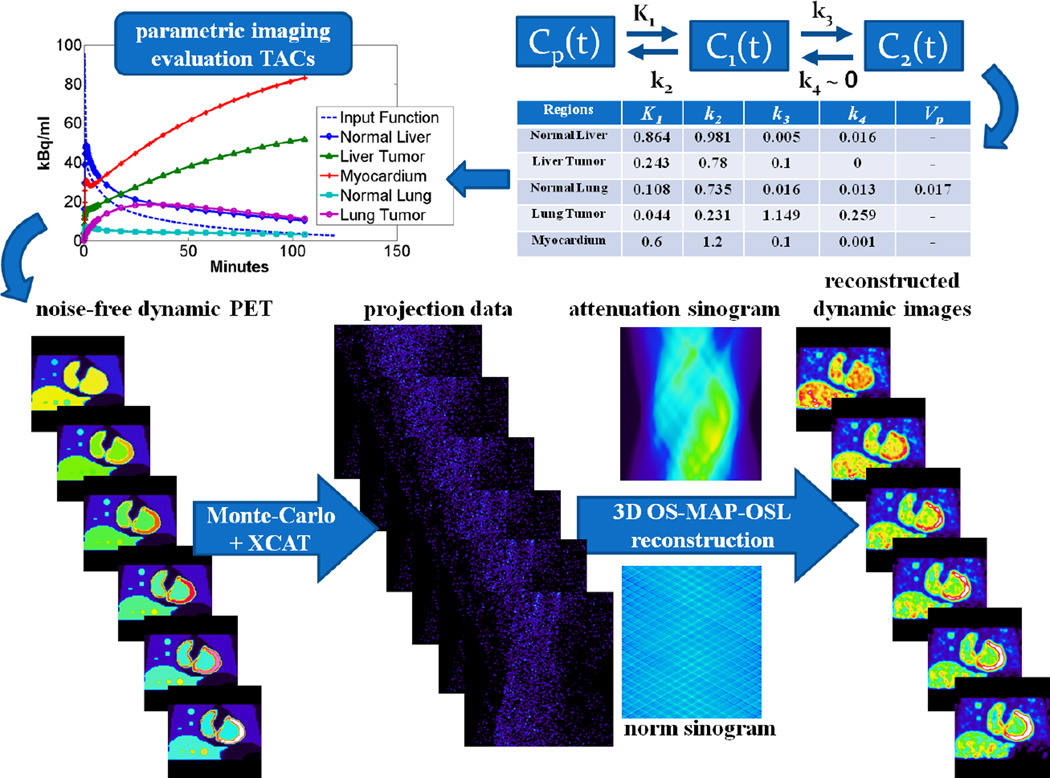

4.1. Production of simulated data

A series of realistic Monte Carlo (MC) simulations were performed to evaluate the parameter estimation methods presented in the preceding section. The Geant4 Application for Tomography Emission (GATE) MC simulation platform was employed to build a model of the GE Discovery RX PET/CT scanner and produce simulated PET projection data. GATE has benefited from the well-validated physics process models of Geant4 toolkit to develop a customized platform capable of simulating nuclear medicine detector systems and acquisition protocols (Jan et al 2011, Karakatsanis et al 2006, 2009, Sakellios et al 2006, Gonias et al 2007). In addition, the highly detailed XCAT human torso voxelized phantom was used for the modeling of the dynamic activity and attenuation distribution (Segars et al 2010).

A representative set of kinetic parameter values (table in figure 7), obtained from an up-to-date literature review (Torizuka et al 1995, Sugawara et al 1999, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss et al 2001 and 2004 and 2006, Okazumi et al 2009, Strauss et al 2007 and 2008, Qiao et al 2007), were applied to the standard 2-tissue compartment FDG kinetic model (figure 1) to generate realistic TACs later assigned to the voxels of appropriate XCAT phantom regions. Thus, XCAT dynamic activity distributions were produced at time frames corresponding to the dynamic cardiac bed frames, according to the proposed multi-bed acquisition protocol (figure 2). Later, the produced dynamic cardiac activity distributions together with the cardiac attenuation map were passed to the MC GATE simulation. Therefore, the total number of simulated events were determined by the noise-free TACs assigned to each voxel.

Figure 7.

Quantitative analysis for a major subset of proposed parametric imaging methods: Plots of CNR vs iterations for a large (15mm diameter) (a) liver tumor and (b) lung tumor. WR driven post-smoothed OLS is not shown, because it exhibits same performance as GRRSC.

Subsequently, the simulated list-mode PET data generated by GATE were binned into a dynamic series of 3D sinograms, each of them resampled based on the bootstrap method and the noise properties of the Poisson distribution to produce multiple noise realizations (Efron and Tibshirani 1993, Haynor and Woods 1989). Then, all generated sinograms were reconstructed to produce dynamic PET images employing the OS-MAP-OSL algorithm implemented in STIR v2.2, an open-source software toolkit (Thielemans et al 2006), though the Bayesian beta parameter was set to 0, thus effectively rendering the OS-EM algorithm. For this study and scanner, a total of 21 subsets and 15 full iterations have been selected. Finally, the correction factors to account for non-uniform detector response and attenuation were calculated and incorporated into the sensitivity image of the OSEM algorithm to correct for those effects within the reconstruction. The flow chart of the process followed to produce the 4D simulated PET data is presented in figure 5.

Figure 5.

A flow chart illustrating the process to generate realistic 4D simulation data.

Moreover, in the current study two groups of tumors were modeled, one for the liver and one for the lung, all located within the same bed position, to compare the statistical estimation performance for a wider range of contrast environments. Each group consists of three spherical tumors with different diameters. Thus, a total of six spherical tumors were simulated: liver1, liver2, liver3, lung1, lung2 and lung3. Indices 1, 2 and 3 correspond to 15mm, 10mm and 5mm diameter respectively. The same kinetic parameters were used for all tumors of the same group. Based on the reported set of kinetic parameter values, lung regions were assigned overall low-uptake kinetics both in tumors and their background, while liver tumors and their background were both associated with relatively higher uptake rates.

4.2. Quantitative analysis

The statistical estimation methods presented in section 3 were comparatively evaluated based on the quantitative metrics of MSE and CNR for specific tumor ROIs drawn in the final Ki parametric images. In this section we present the definitions of the ROI quantitative metrics employed in this study (Table IV).

Table IV.

Definitions of ROI Quantitative Metrics

| ROI quantitative metrics | ||

|---|---|---|

| (24) | (25) | (26) |

| CNR = (Tumor_ROImean/Bkgrd_ROImean−1) / Bkgrd_ROINSD (27) | ||

where denotes the ith voxel from rth noise realization, μi denotes the reference true ith voxel, n is the number of voxels in the ROI and R is the number of noise realizations.

For the simulated data, where the true Ki is known for each voxel of the tumor and its background region, the normalized bias (NBias) of each region can be determined by first calculating NBiasr for noise realization r and, subsequently, averaging over all R noise realizations. In addition, for the calculation of the normalized standard deviation NSD of a simulated ROI, first the NSDi of each voxel i was calculated over all R noise realizations, followed by an averaging over all n voxels of the ROI. However, for the clinical data where only a single realization was available (R=1), a spatial NSD of an ROI was calculated from the following equation, where and fi denotes the ith voxel intensity:

| (28) |

Similarly, the normalized MSEi (NMSEi) was first calculated over multiple realizations for each ith voxel and, later, was averaged over all voxels of an ROI to yield the NMSE for that ROI. The overall NBias, NSD and NMSE metrics for each simulated image were defined as the weighted average of individual ROIs metrics. The sizes of the ROIs were employed as weights. Finally, the metric of contrast to noise ratio CNR has been applied to evaluate the tumor detectability in both simulated and clinical parametric images.

5. Results

5.1. Evaluation of proposed statistical parameter estimation methods

5.1.1. Simulation results

The set of parametric Ki images, produced by the proposed methods, is compared against the true parametric image, as derived from OLS estimation on true noise-free PET dynamic frames. A WR reference value of 0.85 has been selected to determine the hWR and lWR clusters. This WR reference was found to provide the highest CNR in simulated lung tumors for hybrid regression (hyR), which includes GRR in the hWR and OLS followed by post-smoothing in the lWR regions, as motivated in section 3.4.

In figure 6, a collection of parametric images, as estimated from our set of parametric imaging methods, is presented and compared against the true parametric (Ki) image as well as the respective SUV image. The first row comparatively illustrates the Ki images for the major methods examined in this study (OLS, hyR and GRRSC) vs. true Ki and SUV. The middle and bottom rows present Ki images derived by different RR and RRSC methods respectively. Qualitative inspection of the images suggests better CNR for parametric imaging over SUV in tumor regions exhibiting high SUV both in tumor and background, such as the liver tumor.

Figure 6.

Image comparison between our proposed parametric Ki imaging methods, the true Ki image and the SUV (GATE simulation data reconstructed with STIR OSEM algorithm, 21 subsets, 5 iterations).

The quantitative analysis of the simulated data for the liver tumor are presented in figure 7. The charts present the CNR of a large (15mm diameter) (7a) liver and (7b) lung tumor region as a function of the OSEM sub-iterations of the dynamic PET frames for the major ridge regression methods (GRR, GRRSC and hybrid regression hyR) proposed in the current paper against OLS and SUV. The rest of the ridge regression methods (with and withour spatial constraint) resulted in CNR levels lower than hyR and GRRSC and, therefore are not shown to improve clarity of the charts in figure 7 as well as to better illustrate the performance of the major subset of parametric imaging methods proposed here. In both liver and lung tumor regions, hyR and GRRSC both achieve the highest CNR performance among all Patlak imaging methods (figure 7a).

Moreover, in the case of the liver tumor, characterized by high uptake and high background activity levels, all major Patlak methods performed better compared to SUV. On the contrary, for the lung tumor region, where the target and background activity levels were low, SUV imaging resulted in higher CNR levels (figure 7b). We attribute this CNR discrepancy in the parametric images between liver and lung tumor to the fact that the latter is associated in our simulations with relatively lower uptake and background activity. As we further discuss in section 6.1, the higher levels of noise, due to the low activity, in the short dynamic PET frames, relative to SUV images, propagates to the parametric images through the voxel-wise estimation process. In addition, as we have concluded in a recent study (Karakatsanis et al 2013c) the conventional Patlak model tends to underestimate Ki and thus reduce tumor contrast when the tumor region is characterized by considerably reversible kinetics, i.e. non-negligible k4 parameter, as is the case with our simulated lung tumor (see table in figure 5). However, even in such low contrast and highly noisy imaging environments, GRRSC and hyR methods outperform the rest of parameter estimation methods and approach SUV in terms of CNR performance.

The effect of kinetic correlation driven thresholding on the parametric images for OLS, GRR and GRRSC methods is illustrated in figures 8a and 8b. As we observe from the images, and quantitatively confirm from the CNR analysis, there is a range of WR reference (threshold) values [0.8–0.9] for which the CNR is maximized, while for higher WR, contrast and quantification are deteriorated. All three methods exhibit similar trends as a function of WR reference, with GRRSC achieving the highest CNR.

Figure 8.

(a) Simulated images illustrating the effect of kinetic WR driven thresholding on PET parametric imaging and (b) quantitative analysis of a large (15mm diameter) liver tumor (liver1) CNR in parametric images produced by OLS, GRR and GRRSC estimation methods for various WR reference (threshold) levels, against CNR in SUV. The latter CNR is independent of the threshold, but is plotted for comparisons.

The total acquisition time of whole body PET parametric imaging can be significantly reduced by omitting one or two of the late six total dynamic frames at each bed. The effect of limited number of frames on the measured liver tumor CNR of the final parametric images, with respect to SUV, is presented qualitatively and quantitatively in figures 9a and 9b, respectively. The image quality is affected as we gradually omit the last frames (i.e. shorten total scan duration), however, the quantitative CNR analysis suggests that we can afford skipping the last two whole body scans and still achieve higher CNR than SUV when hybrid regression, OLS or GRRSC regression is applied.

Figure 9.

(a) The effect of utilizing 6, 5, 4 or just 3 dynamic frames per bed for three different estimation methods in whole body PET parametric imaging (simulated data) and (b): Quantitative analysis of this effect on a medium-sized (10mm diameter) liver tumor (liver2) CNR in parametric imaging, against SUV. SUV CNR is independent of the number of dynamic frames and is plotted only for comparisons. Note that OLS, GRR and GRRSC GRR plots almost coincide with each other implying very similar CNR performance with respect to number of frames.

In order to quantitatively assess the accuracy in the Ki estimates of PET parametric images, we plotted, for a set of regions of interest (ROIs), the CNR in the liver tumor against the ensemble RMSE for a range of full OSEM iterations (figure 10a) and a range of passes per bed (figure 10b). For comparative evaluation we repeated this process for a range of parametric imaging methods including OLS, post-smoothed OLS (smOLS), GRR, GRRSC and hybrid regression (hyR).

Figure 10.

(a) Quantitative analysis of 1/CNR vs. ensemble RMSE for the 15mm diameter liver tumor for a range of full OSEM iterations and (b) for a range of passes per bed for different parametric images. WR-driven post-smoothing of OLS performance is not shown, because it is very similar with GRRSC in all cases. For both diagrams, proximity to the origin (i.e. high CNR and low RMSE) of a point or curve is a metric of good performance. In (a) the 1/CNR values increase with increasing number of iterations, while in (b) it decreases with increasing number of passes.

The results in figure 10a evidently suggest that our proposed hybrid regression method achieves the best CNR vs. MSE performance among all statistical estimation methods examined for the liver tumor. Furthermore, as the results of figure 10b demonstrate, hybrid regression retains this superiority even when the first 5 passes per bed are utilized. However, when only the first 4 passes are acquired, hybrid regression performs equivalently to GRRSC, but better than the rest of the methods. In addition, both figures 10a and 10b suggest relatively high sensitivity of MSE in hybrid regression to the kinetic WR threshold applied for the clustering. A WR threshold between 0.6 and 0.8 provides the best result depending on the tumor ROI.

5.1.2. Clinical results

A clinical whole body FDG PET study involving six patients was conducted at the Johns Hopkins PET center to demonstrate clinical feasibility and provide validation of the proposed methods in clinical environments. All patients were scanned according to our proposed 4D whole body acquisition protocol, followed by a conventional SUV scan 60min post injection. The input function was derived from the cardiac bed frames of the protocol, as described in section 2.2.

Our enhanced statistical estimation methods were applied on the OSEM reconstructed images to produce whole body PET parametric Ki images, as illustrated in figure 11a for one of the patients. OLS, hybrid regression and GRRSC exhibited higher contrast to noise ratio (CNR) than SUV in a high-uptake lung tumor region. Also the liver background signal is effectively removed in most of the parametric Ki images. The quantitative CNR results in figure 11b indicate superior performance of certain parametric imaging methods over SUV and, more particularly, designate hybrid regression as the parameter estimation method delivering the highest CNR in the clinical data.

Figure 11.

(a): A collection of clinical whole body PET parametric Ki images, as obtained with GE Discovery RX scanner from one of the patients examined, compared against SUV image. The lung tumor is visible in the upper left part of all images. (b): Lung tumor ROI contrast-to-noise (CNR) analysis for a collection of patient Patlak methods against SUV, as measured from the patient images presented in right section

Apart from hybrid regression, we have observed enhanced CNR performance for most of the RRSC schemes, and more particularly for the mixed GRRSC_GRR scheme. As we discuss in appendix C, the RRSC estimators tend to be associated with very large values of ridge parameters, resulting in strong enforcement of the prior (constraint). However the prior derived from noisy data may be characterized by low CNR or high MSE as a result of post-smoothing operations. Therefore, RRSC in whole body PET can result in images very similar to the prior/constraint, i.e. post-smoothed conventional Patlak in our case. However, for the mixed GRRSC_GRR scheme, smaller ridge parameter values are selected, and thus, a milder enforcement of the prior takes place.

Figure 12 demonstrates the effects of kinetic correlation driven thresholding (left), for a number of WR threshold levels, as well as (right) that of the removal of later dynamic frames from the estimation process. In figure 12a we observe significant CNR enhancement, even by simple visual inspection, in tumors with well defined boundaries, when correlation based thresholding is applied in OLS, RR and GRRSC schemes. Moreover, in figure 12b contrast and quantification are maintained at sufficient levels in the OLS, hyR and GRRSC parametric images, when removing the last one or two dynamic frames, allowing for shorter acquisition times of 30min.

Figure 12.

Clinical demonstration of the effect of (a) kinetic correlation driven thresholding and (b) reduction of later dynamic frames on clinical whole body PET parametric imaging

6. Discussion

6.1 Effect of contrast environments on parametric estimation performance

In the current study, a range of different time activity curves for tumors and their background regions were examined. As a result, a range of different CNR environments were produced both for the PET dynamic frames and the resulting parametric Ki images. These environments can be grouped into three characteristic classes commonly observed in oncology FDG PET studies:

high uptake rate tumors surrounded by high, but constant background activity,

low-uptake rate tumors surrounded by low uptake background, and

high uptake rate tumors surrounded by low uptake background.

Examples of these three classes include (a) simulated liver tumor in section 4.1 and 5.1, figures 5, 6, 8 and 9), (b) simulated lung tumor also in section 4.1, and (c) the large lung tumor observed in one of the clinical FDG data in section 5.2, figures 11 and 12.

In particular, for the tumor-to-background (TBR) contrasts of the first class (e.g. simulated liver tumor region), most of the parametric imaging methods examined, including their major subset of OLS, GRR, GRRSC and hyR, achieve higher CNR than SUV. The high, but constant activity in the background of those regions is considerably decreased in nearly all Ki images, which is the very strength behind the proposed methodology, resulting in a significant increase of the tumor contrast and subsequently CNR relative to SUV for all the methods of the major subset above. In this environment, the noise in the background may still be significant due to the voxel-wise parameter estimation process, however it is outweighed by the contrast enhancing ability of parametric imaging. Hybrid regression was also quantified to outperform its statistical counterparts, for reasons explained in section 3.4.

Additionally, for the TBR contrasts of the second class, the high noise levels induced by the low count statistics of both the tumor and background regions results in high noise which is further amplified by the short length of the dynamic acquisition frames compared to later SUV frame at each bed position. Then the noise is propagated through the voxel-wise parameter estimation process to the parametric images leading to a decrease of CNR in Ki images relative to SUV. In addition, as we have demonstrated in a recent study (Karakatsanis et al 2013c), the conventional Patlak model (Patlak et al 1983) tends to underestimate Ki in tumor regions exhibiting reversible kinetics, i.e. non-negligible k4, as is the case with our simulated lung tumor (section 4.1). Consequently, k4 reversibility in tumors impacts their Patlak Ki tumor to background contrast. However, hybrid regression and GRRSC are still able to achieve, despite the highly noisy and low contrast environment, not only the highest CNR among the rest of parametric imaging methods, but also approach SUV CNR performance.

Finally, for the third type of contrast environments, most of the Ki imaging methods perform similarly to SUV imaging. A small subset of regression schemes, such as GCV methods, SRR HK and SRR GM, even though they achieved high CNR levels, they did not outperform SUV, possibly because the associated ridge parameters (Table III) induced a relatively higher variance for the particular contrast environment and also because SUV CNR is already quite high. However, even in that case, GRRSC and hybrid regression may provide higher CNR relative to SUV. In addition, hybrid regression can also result in reduction of MSE for the same CNR, relative to GRRSC, owing to its capability of combining ridge regression and post-smoothed OLS to suppress noise in the background and improve CNR vs. MSE trade-off (section 5.1.1).

Therefore, we propose, as complementary to SUV, the application of OLS, as also suggested in the companion paper (Karakatsanis et al 2013b), or task-based hybrid Ki imaging, as shown in the current study, to ensure maximum performance in all possible tumor contrast environments observed in clinical FDG PET oncology studies.

As a future prospect, we are currently preparing a larger and more systematic clinical survey of patient whole body parametric imaging exams at our PET center to enable observer studies in order to assess the impact of each of the proposed parametric imaging methods both in treatment management and lesion detectability.

6.2 Selection of the Patlak kinetic correlation-coefficient (WR) reference value

The flow chart of the algorithm for WR-driven hybrid regression (section 3.5, figure 4) as well as the quantitative CNR vs. MSE analysis (figure 10a) of the simulated data demonstrate the significance in selecting an appropriate WR reference value to classify the voxels of a parametric image into the lWR and hWR clusters. By definition (section 3.4), WR can accept values between −1 and +1, with this study focusing on the positive range of correlations (0,1) as the Patlak model expects. By selecting very high WR reference values close to 1 (e.g. >0.95), the criteria for a voxel TAC to be considered highly correlated with Patlak linear kinetics becomes very strict. Consequently, it becomes more likely to treat a voxel as if it belongs to a low activity background region, whereas it actually belongs to a high uptake rate tumor region. On the other hand, setting WR reference value to very low values (e.g. <0.6) makes the criteria of Patlak goodness-to-fit very mild.

Therefore, an appropriate region of WR reference values should be initially defined such as to minimize the mismatch between the actual statistical quality of a reconstructed voxel TAC and our expectation of this quality after the binary classification of the voxel TACs in lWR and hWR clusters. For the wide range of dynamic contrast environments (section 6.1) examined in this and the companion study (Karakatsanis et al 2013b), we concluded that an initial range of WR reference values [0.6 0.95] is appropriate, as it includes most of the possible WR values capable of appropriately separating tumor from background regions. Later, one can determine the specific WR reference value which maximizes the performance according to a task-based quantitative metric. For example, if the observer's task is to enhance the diagnostic value, the specific WR reference producing hybrid Ki images of highest CNR should be selected, while if the task is treatment response assessment, WR value yielding the minimum MSE in hybrid Ki images should be chosen. In fact, the free nature of WR reference value provides WR-based methods with task-based performance optimization capabilities.

6.3 Direct vs. indirect whole-body parametric imaging

The current study involves indirect estimation of parametric images from OSEM reconstructed dynamic whole-body FDG images acquired over a period of 30–45m post injection employing the standard Patlak linear model. We are investigating (Karakatsanis et al 2013a) an extension of the proposed framework to the direct 4D parametric image reconstruction domain (Wang et al 2008, Tsoumpas et al 2008a and b, Rahmim et al 2009, Tang et al 2010, Wang and Qi 2010) to directly estimate parametric images from dynamic sinogram data to further limit the noise induced by the limited scan time of each bed.

By integrating kinetic parameter estimation within the OSEM iterative reconstruction framework, direct 4D parametric image reconstruction is going to allow for (i) more accurate modeling of the Poisson noise characteristics into the parameter estimation process, (ii) more efficient utilization of all available 4D PET data, (iii) acceleration the generation of parametric images and (iv) an efficient solution to the problem of parameter estimation in overlapped slices between adjacent beds. On the other hand, the current indirect parametric imaging framework, proposes a more easily adoptable approach for clinical applications.

7. Summary and Conclusions

In the current study, within the context of whole-body PET parametric imaging, a) we have evaluated a set of advanced ridge regression methods with and without spatial constraint and b) proposed a novel hybrid regression approach to achieve superior trade-off between diagnostic CNR and quantitative MSE performance in the final parametric images. Our aim has been to carefully assess a proposed paradigm shift towards dynamic whole-body PET imaging, potentially allowing for quantitative whole-body assessment of patient response to treatments over short and long time periods without compromising high CNR in suspected tumor regions. Whether the observer's task is to maximize CNR (e.g. diagnostic reliability) or to minimize MSE (e.g. quantification in treatment response monitoring), we present a generalized whole body PET parametric imaging framework, equipped with appropriate acquisition protocols and statistical enhancement tools, that enables it to address both tasks challenges simultaneously and, thus, contribute to its integration in the routine clinical PET environment, as a competitive alternative or complement to SUV.

Our first clinical demonstration of dynamic whole-body FDG PET imaging, as illustrated in figures 11 and 12, shows the clinical feasibility of the proposed method and suggests enhanced tumor-to-background contrast for the parametric images with respect to conventional SUV images. Hybrid regression provides the highest CNR by efficiently handling the noise in the background regions. In addition, the quantitative analysis in figures 7 and 10 indicates hybrid regression as the method with the best CNR vs. MSE trade-off performance. Hybrid regression outperforms SUV and a range of kinetic parameter estimation methods, because it efficiently utilizes kinetic correlation based clustering to determine which regression method is the most appropriate at each voxel TAC. Moreover, even though GRRSC approaches the CNR levels of hybrid regression, it cannot match its low MSE performance for a given CNR level.

Overall, we have demonstrated that the performance of the variety of statistical kinetic modeling methods investigated with respect to conventional SUV imaging was especially enhanced for tumor contrast environments with high background (e.g. liver tumors). In other contrast environments, performance of the statistical regression methods applied to dynamic whole-body imaging did not collectively exceed SUV imaging. However, hybrid regression outperformed the other statistical techniques, and even SUV imaging in some low-background environments. Overall, the proposed methodology promises to provide powerful and complementary information to SUV imaging, and potentials of enhanced performance. Finally, we note that the current prospects of PET technology aiming at larger axial FOVs and faster acquisitions can serve as an even stronger driving force for a wide adoption of the proposed parametric imaging framework into routine clinical PET imaging protocols.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr William P. Segars and the openGATE collaboration for providing us with the XCAT phantom and the GATE software, respectively. Furthermore, we would also like to acknowledge Dr Abdel K Tahari, Dr Joyce Mhlanga and John Crandall for assisting us in recruiting patients for our clinical studies, as well as Hassan Mohy-ud-Din for discussions regarding parameter estimation methods. This work was supported by the NIH grant 1S10RR023623.

Appendix A

Limitations of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS)

Hoerl and Kennard (1970a, b) demonstrated the limitations of OLS by emphasizing on the properties of the eigenvalues ofX′X. Consider L1 the distance of βOLS from its expected value β. Then:

| (A1) |

In fact, the expected squared distance of βOLS from β is the definition for the total mean squared error (MSE) of βOLS. If the eigenvalues (m = 2 in this work) of X′X are λmax = λ1 ≥ λ2 = λmin > 0, then the average and the variance of the squared distance of βOLS from β is given, respectively, by

| (A2) |

| (A3) |

Equivalently, the expected squared length of βOLS is:

| (A4) |

Thus, when multi-collinearity is present, i.e. when λmin ≪ 1, the lower bounds for the mean and variance of the squared distance of βOLS from β, as well as for the length of βOLS, becomes very high.

Appendix B

Ridge Regression (RR)

B.1 Transformation of the regression problem to an orthogonal space

The linear regression problem, as defined in equation (5), can be transformed to a new space where diagonalization is achieved. Suppose an orthogonal matrix D (D′ = D−1) such that X′X = DΛD′, or D′X′XD = Λ, where Λ = diag (λ1, λ 2) are the eigenvalues of X′X. Let Z = XD and α = D′β be the transformed regression matrix and transformed regression parameter vector respectively. Now Z′Z = Λ is a diagonal matrix. The orthogonal form of the regression problem is (Hoerl and Kennard 1970a, b):

| (B1) |

The formulation of the problem in the transformed domain has special advantages for straightforward optimization of the ridge parameters (B.2). The estimators for OLS, SRR and GRR schemes in the orthogonal space (αOLS, αSRR, αGRR) as well as the objective functions are presented in table V.

Table V.

OLS and Ridge Regression After Orthogonalization

| Optimal solutions | Minimization problem |

|---|---|

| (B2) | αOLS = (Z′Z)−1 Z′Y (B5) |

| (B3) | αSRR = (Z′Z + hIp)−1 Z′Y, h > 0 (B6) |

| (B4) | αGRR = (Z′Z + Hα)−1 Z′Y, Hα = diag(h1α, h2α), hiα > 0 (B7) |

By substituting Z = XD in eq. (B7), we derive:

| (B8) |

Now, βGRR can be expressed with respect to Hα:

| (B9) |

By considering Hβ = DHαD′, eq. (B2) can be rewritten:

| (B10) |

Hence, in GRR we can calculate the ridge parameters Hα in the orthogonal space and transform them back to the original space, as follows: Hβ = DHαD′. Note, while Hα is diagonal, this is not necessarily true for Hβ. However, when all elements of the diagonal matrix Hα are equal to h (hiα = h, i = 1, 2), GRR is reduced to SRR. Then, Hβ = DHαD′ = Hα, i.e. both matrices are diagonal and the orthogonal transformation is obsolete. To summarize:

| (B11) |

B.2 Theoretical and practical approaches in optimizing the ridge parameters hi for RR scheme

The MSE of the parameter vectors βSRR and βGRR are equal to the MSE of αSRR and αGRR, respectively, because orthogonal transformations maintain distances. Thus:

| (B12) |

| (B13) |

In the case of GRR, the optimal ridge parameters, minimizing MSE, are determined as follows:

| (B14) |

We emphasize that this expression is only valid, and derivable as such, in the abovementioned transformed space (though invoked in some works, without justification, in the original space). However, the optimal values hiα as indicated by equation (B14), depend on the regression error variance σ2 and the true regression parameters αi, which are both unknowns. Therefore, Hoerl and Kennard (1970a, b), in the context of generalized ridge regression, proposed the following equation to estimate the optimal ridge parameters from the actual data:

| (B15) |

where αOLSi is the ith element of αOLS = D′βOLS, the unbiased OLS estimator of α = D′β, while σ̂2 is the unbiased OLS estimate of the regression error, derived by dividing the RSS by the statistical degrees of freedom n−m (m = 2):

| (B16) |

Also, in the context of SRR, a collection of methods to optimize the single ridge parameter have been proposed which we have presented in the left column of Table III (Hoerl et al 1975, Allen 1971, Lawless and Wang 1976, Golub et al 1979, Kibria 2003).

Appendix C

Ridge Regression with spatial constraint (RRSC)

C.1 Comparing MSE of ridge regression with and without spatial constraint

The MSE for the SRRSC and GRRSC schemes are presented below:

| (C1) |

| (C2) |

From equations (B12), (B13), (C1) and (C2) we conclude that, if our spatial constraint αSC is selected such that , i = 1,2, i.e. if αSC is a “good prior”, for a given Hα :

| (C3) |

C.2 Optimizing ridge parameters hi in the RRSC scheme

The optimal ridge parameters minimizing MSE are determined as follows:

| (C4) |

By substituting the optimal GRR and GRRSC ridge parameters (B14) and (C4) into the corresponding MSE equations (B13) and (C2), we arrive at:

| (C5) |

| (C6) |

demonstrating an advantage of ridge regression over OLS in terms of MSE. A collection of methods in RRSC framework to estimate the optimal ridge parameters from the data is demonstrated in the right column of Table III. Note that the denominator can be very small when the constraint/prior is very similar to the OLS estimate. In this case, the proposed ridge parameters and the penalty terms in equations (19) and (20) are increasing, forcing the RRSC estimators to become very similar to the prior estimates. Consequently, if the selected prior is inappropriate, RRSC schemes may not perform better than RR schemes. This is the motivation for our proposed GRRSC_GRR technique (end of section 3.5), wherein the optimal ridge parameters (B14) for the GRR scheme are substituted into the GRRSC framework, which according to C3, should provided an attractive alternative to the GRR framework.

Contributor Information

Nicolas A. Karakatsanis, Email: nkarakatsanis@jhmi.edu.

Arman Rahmim, Email: arahmim1@jhmi.edu.

References

- Adams M, Turkington T, Wilson J, Wong T. A systematic review of the factors affecting accuracy of SUV measurements. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2010;vol. 195(no. 2):310–320. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D. Mean Square Error of Prediction as a Criterion for Selecting Variables Technometrics. 1971;Vol. 13(No. 3):469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Burger I, Burger C, Berthold T, Buck A. Simplified quantification of FDG metabolism in tumors using the autoradiographic method is less dependent on the acquisition time than SUV. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2011;38:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrtek M, O'Sullivan F, Muzi M, Spence AM. An Adaptation of Ridge Regression for Improved Estimation of Kinetic Model Parameters From PET Studies. IEEE Trans. on Nucl. Science. 2005;Vol. 52(No. 1) [Google Scholar]

- Castell F, Cook G. Quantitative techniques in 18-FDG PET scanning in oncology. British Journal of Cancer. 2008;vol. 98(no. 10):1597–1601. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlbom M, Hoffman E, Hoh C, Schiepers C, Rosenqvist G, Hawkins R, Phelps M. Whole-body positron emission tomography: Part i. methods and performance characteristics. J of Nucl. Med. 1992;vol. 33(no. 6):1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Georgoulias V, Eisenhut M, Herth F, Koukouraki S, Macke H, Haberkorn U, Strauss L. Quantitative assessment of SSTR2 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer using 68 Ga-DOTATOC PET and comparison with 18 F-FDG, PET. Eur J Nucl. Med. and Mol. Imaging. 2006;vol. 33(no. 7):823–830. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-0063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss L, Burger C. Quantitative PET studies in pretreated melanoma patients: a comparison of 6-[18F] fluoro-L-dopa with 18F-FDG and 15O-water using compartment and noncompartment analysis. J Nucl. Med. 2001;vol. 42(no. 2):248–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss L, Burger C, Ruhl A, Irngartinger G, Stremmel W, Rudi J. Prognostic aspects of 18F-FDG PET kinetics in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma receiving FOLFOX chemotherapy. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;vol. 45(no. 9):1480–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss L, Schwarzbach M, Burger C, Heichel T, Willeke F, Mechtersheimer G, Lehnert T. Dynamic PET 18F-FDG studies in patients with primary and recurrent soft-tissue sarcomas: impact on diagnosis and correlation with grading. J. of Nucl. Med. 2001;vol. 42(no. 5):713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss L, Schwarzbach M, Burger C, Heichel T, Willeke F, Mechtersheimer G, Lehnert T. Dynamic PET 18F-FDG studies in patients with primary and recurrent soft-tissue sarcomas: impact on diagnosis and correlation with grading. J Nucl. Med. 2001;Vol. 42(No. 5):713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the Bootstrap, CRC ed. New York: Chapman Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Facey K, Bradbury I, Laking G, Payne E. Overview of the clinical effectiveness of positron emission tomography imaging in selected cancers. Health Technology Assessment. 2007;Vol. 11(No. 44) doi: 10.3310/hta11440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli G, Indovina L, Calcagni ML, Mansi L, Giordano A. The quantification with FDG as seen by a physician. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2013;40:720–730. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub G, Heath M, Wahba G. Generalized Cross-Validation as a Method for Choosing a Good Ridge Parameter. Technometrics. 1979;Vol. 21(Issue 2) [Google Scholar]

- Gonias P, Bertsekas N, Karakatsanis N, Saatsakis G, Nikolopoulos D, Tsantilas X, Loudos G, Sakellios N, Gaitanis A, Papaspyrou L, Daskalakis A, Liaparinos P, Cavouras D, Kandarakis I, Panyiotakis G. Validation of a GATE Model for the simulation of the Siemens PET/CT Biograph 6 Scanner. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A. 2007;Vol. 569(Issue 2):368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberg L, Hunter G, Alpert N, Choi N, Babich J, Fischman A. The dose uptake ratio as an index of glucose metabolism: Useful parameter or oversimplification? J. of Nucl. Med. 1994;vol. 35(no. 8):1308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynor DR, Woods SD. Resampling estimates of precision in emission tomography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 1989;vol. 8(no. 4):337–343. doi: 10.1109/42.41486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerl A, Kennard R. Ridge Regression: Biased Estimation for Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics. 1970a;Vol. 12(Issue 1):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerl A, Kennard Ridge Regression: Applications to Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics. 1970a;Vol. 12(Issue 1):69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hoerl A, Kennard R, Baldwin K. Ridge regression:some simulations. 1975;Vol. 4(No. 2):105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. Anatomy of SUV. Nucl. Med. and Biol. 2000;vol. 27(no. 7):643–646. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Phelps ME, Hoffman EJ, Sideris K, Selin C, Kuhl DE. Nonivasive determination of local cerebral metabolic rate of glucose in man. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1980;238:E69–E82. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1980.238.1.E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter GJ, Hamberg LM, Alpert NM, Choi NC, Fischman AJ. Simplified measurement of deoxyglucose utilization rate. J Nucl Med. 1996;Vol. 37(No. 6) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustinx R, Benard F, Alavi A. Whole-body FDG-PET imaging in the management of patients with cancer. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 2002;vol. 32(no. 1):35–46. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2002.29272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan S, et al. GATE V6: a major enhancement of the GATE simulation platform enabling modeling of CT and radiotherapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011;vol. 56:881. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/4/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneta T, Takai Y, Iwata R, Hakamatsuka T, Yasuda H, Nakayama K, Ishikawa Y, Watanuki S, Furumoto S, Funaki Y, Nakata E, Jingu K, Tsujitani M, Masatoshi I, Fukuda H, Takahashi S, Yamada S. Initial evaluation of dynamic human imaging using 18F-FRP170 as a new PET tracer for imaging hypoxia. Ann of Nucl Med. 2007;Vol 21(Issue 2):101–107. doi: 10.1007/BF03033987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Lodge M, Mohy-ud-Din H, Tahari A, Zhou Y, Segars W, Wahl R, Rahmim A. Enhanced Whole-Body PET Parametric Imaging Using Hybrid Regression and Thresholding Driven by Kinetic Correlations; IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. Conf. Record; 2012b. [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Lodge M, Tahari AK, Zhou Y, Wahl RL, Rahmim A. Dynamic whole body PET parametric imaging: I. Concept, acquisition protocol optimization and clinical application. Phys in Med and Biology. 2013b doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/20/7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Lodge M, Wahl RL, Rahmim A. Direct 4D whole-body PET/CT parametric image reconstruction: Concept and comparison vs. indirect parametric imaging. J Nucl Med 2013. 2013a;54(Supplement 2):2133. [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Lodge M, Zhou Y, Mhlanga J, Tahari A, Chaudhry M, Segars W, Wahl R, Rahmim A. Dynamic Multi-Bed FDG PET imaging: Feasibility and optimization; IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. Conf. Record; 2011. pp. 3863–3870. [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Lodge M, Zhou Y, Mhlanga J, Tahari A, Wahl R, Rahmim A. Towards Parametric Whole-Body FDG PET/CT Imaging: Potentials for Enhanced Tumor Detectability. J. Nucl. Med. 2012a;vol. 53(suppl. 1):1236. [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Loudos G, Nikita K. A Methodology for Optimizing the Acquisition Time of a Clinical PET Scan Using GATE; IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. and Med. Imaging Conf. Record; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Sakellios N, Tsantilas X, Dikaios N, Tsoumpas C, Nikita K, Lazaro D, Loudos G, Louizi A, Valais I, Nikolopoulos D, Malamitsi J, Kandarakis I. A Comparative Evaluation of Two Commercial PET Scanners using GATE. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A. 2006;Vol 569(Issue 2):368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Karakatsanis N, Zhou Y, Lodge M, Casey ME, Wahl RL, Rahmim A. Quantitative Whole-Body Parametric PET Imaging Incorporating a Generalized Patlak Model; IEEE Nucl Sci. Symp. and Med. Imaging Conf. Record; 2013c. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes J., Jr SUV: Standard uptake or silly useless value? J. of Nucl. Med. 1995;vol. 36(no. 10):1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibria B. Performance of Some New Ridge Regression Estimators. Comm. in Statistics – Simulation and Computation. 2003;Vol. 32(Issue 2) [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Gupta N. Dependency of standardized uptake values of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose on body size: comparison of body surface area correction and lean body mass correction. Nuclear medicine communications. 1996;vol. 17(no. 10):890. doi: 10.1097/00006231-199610000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Gupta N, Chandramouli B, Alavi A. Standardized uptake values of FDG: body surface area correction is preferable to body weight correction. J. of Nucl. Med. 1994;vol. 35(no. 1):164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota K, Itoh M, Ozaki K, Ono S, Tashiro M, Yamaguchi K, Akaizawa T, Yamada K, Fukuda H. Advantage of delayed wholebody FDG-PET imaging for tumour detection. Eur. J. of Nucl Med and Mol Imaging. 2001;vol. 28(no. 6):696–703. doi: 10.1007/s002590100537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless J, Wang P. A simulation study of ridge and other regression estimators. Comm. In Statistics-Theory and Methods. 1976;Vol. 5(Issue 4) [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen-Kallio S, Nagren K, Lehikoinen P, Ruotsalainen U, Teras M, Joensuu H. Carbon-11-methionine and PET is an effective method to image head and neck cancer k. J. of Nucl. Med. 1992;vol. 33(no. 5):691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt D, Snee R. Ridge Regression in Practice The American Statistician. 1975;Vol. 29(Issue 1) [Google Scholar]

- Okazumi S, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Schwarzbach M, Strauss L. Quantitative, dynamic 18F-FDG-PET for the evaluation of soft tissue sarcomas: relation to differential diagnosis, tumor grading and prediction of prognosis. Hel. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;vol. 12(no. 3):223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan F, Saha A. Use of Ridge Regression for Improved Estimation of Kinetic Constants from PET data. IEEE Trans on Med Imaging. 1999;Vol. 18(No. 2) doi: 10.1109/42.759111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlak C, Blasberg R. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. Generalizations. J. of Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;vol. 5(no. 4):584–590. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patlak C, Blasberg R, Fenstermacher J. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1983;vol. 3(no. 1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H, Bai J, Chen Y, Tian J. Kidney Modeling for FDG Excretion with PET. Int. J. of Biom. Imaging. 2007;vol. 2007:632–634. doi: 10.1155/2007/63234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmim A, Cheng J-C, Blinder S, Camborde M-L, Sossi V. Statistical dynamic image reconstruction in state-of-the -art high-resolution PET. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005;vol. 50:4887–4912. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/20/010. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmim A, Tang J, Zaidi H. Four-dimensional (4D) image reconstruction strategies in dynamic PET: Beyond conventional independent frame reconstruction. Med Phys. 2009;Vol. 36(Issue 38):3654. doi: 10.1118/1.3160108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadato N, Tsuchida T, Nakaumra S, Waki A, Uematsu H, Takahashi N, Hayashi N, Yonekura Y, Ishii Y. Non-invasive estimation of the net influx constant using the standardized uptake value for quantification of FDG uptake of tumours. Eur. J. of Nucl. Med. and Mol. Imaging. 1998;vol. 25(no. 6):559–564. doi: 10.1007/s002590050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakellios N, Rubio JL, Karakatsanis N, Kontaxakis G, Loudos G, Santos A, Nikita KS, Majewski S. GATE simulations for small animal SPECT/PET using voxelized phantoms and rotating-head detectors. IEEE Nucl Sci. Symp and Med. Imag. Conf. 2006;Vol. 4 [Google Scholar]

- Scheffe H. The Analysis of Variance. Chapters 1 and 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Segars W, Sturgeon G, Mendonca S, Grimes J, Tsui B. 4D XCAT phantom for multimodality imaging research. J Medical Physics. 2010;vol. 37:4902. doi: 10.1118/1.3480985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Sakurada O, Shinohara M. The (C-14) deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem. 1977;28:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss L, Klippel S, Pan L, Schonleben K, Haberkorn U, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A. Assessment of quantitative FDG PET data in primary colorectal tumors: which parameters are important with respect to tumor detection? Eur J Nucl. Med. and Mol. Imaging. 2007;vol. 34(no. 6):868–877. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss L, Koczan D, Klippel S, Pan L, Cheng C, Willis S, Haberkorn U, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A Impact of angiogenesis-related gene expression on the tracer kinetics of 18F-FDG in colorectal tumors. J Nucl. Med. 2008;vol. 49(no. 8):1238–1244. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara Y, Zasadny K, Grossman H, Francis I, Clarke M, Wahl R. Germ cell tumor: Differentiation of viable tumor, mature teratoma, and necrotic tissue with FDG PET and kinetic modeling. Radiology. 1999;vol. 211(no. 1):249–256. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99ap16249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Kuwabara H, Wong DF, Rahmim A. Direct 4D reconstruction of parametric images incorporating anato-functional joint entropy. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55(15):4261–4272. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/15/005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thielemans K, Mustafovic S, Tsoumpas C. STIR: software for tomographic image reconstruction release 2. IEEE Nucl. Sci. Symp. Conf. Record. 2006;vol. 4:2174–2176. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/4/867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torizuka T, Tamaki N, Inokuma T, Magata Y, Sasayama S, Yonekura Y, Tanaka A, Yamaoka Y, Yamamoto K, Konishi J. In vivo assessment of glucose metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma with FDG-PET. J. Nucl. Med. 1995;vol. 36(no. 10):1811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend D. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 2008;vol. 38(no. 3):152–166. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoumpas C, Turkheimer F, Thielemans K. A survey of approaches for direct parametric image reconstruction in emission tomography. Med. Phys. 2008a;Vol. 35(Issue 9):3963. doi: 10.1118/1.2966349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoumpas C, Turkheimer F, Thielemans K. Study of the direct and indirect parametric estimation methods of linear models in dynamic positron emission tomography. Med Phys. 2008b;Vol. 35:1299. doi: 10.1118/1.2885369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl R, Buchanan J. Principles and practice of positron emission tomography. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]