Abstract

Celiac disease is a chronic immune-mediated multisystem disorder that may affect several organs. Liver abnormalities are common extraintestinal manifestations of celiac disease. Isolated hypertransaminasemia, with mild or nonspecific histologic changes in the liver biopsy, also known as “celiac hepatitis”, is the most frequent presentation of liver injury in celiac disease. Both, histologic changes and liver enzymes reverse to normal after treatment with a gluten-free diet in most patients. Celiac disease may also be associated with severe forms of liver disease and/or coexist with other chronic liver disorders (i.e., autoimmune liver diseases). The mechanisms underlying liver injury in celiac disease are poorly understood. Predisposition to autoimmunity by shared genetic factors (i.e., HLA genes) as well as the systemic effects of abnormal intestinal permeability, cytokines, autoantibodies, and/or other yet undefined biologic mediators induced by gluten exposure in susceptible persons may play a pathogenic role. The aims of this article are 1) to review the spectrum of liver injury related to celiac disease and 2) to understand the clinical implications of celiac disease in patients with chronic liver disorders.

Keywords: autoimmune, hepatitis, cirrhosis, serology, liver

Celiac disease (CD) is a multisystem chronic immune-mediated disorder that affects around 1% of the general population worldwide.1 CD is a permanent intolerance to the grain proteins collectively called “gluten” (present in wheat, barley, and rye) that causes damage to the mucosa of the small intestine and revert to normal in most patients after the exclusion of gluten from the diet. 2 Besides the hallmark of small-intestine injury, CD may affect other organs such as the liver. A wide spectrum of liver abnormalities has been described as either caused by CD or merely associated with CD.3 CD itself may injure the liver but also may modify the clinical impact of chronic liver diseases when they coexist. The aims of this article are 1) to review the spectrum of liver injury related to celiac disease with particular emphasis on “celiac hepatitis” and 2) to understand the clinical implications of the diagnosis of celiac disease in patients with chronic liver disorders.

Celiac hepatitis

Definition

Celiac hepatitis can be defined by the presence of liver injury (abnormal liver tests and/or histological changes in the liver biopsy) in patients with confirmed CD that resolves after treatment with a gluten-free diet (Table 1). The clinical spectrum of liver disease in CD ranges from mild asymptomatic alteration of liver tests to severe liver failure.4, 5

Table 1.

Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Celiac hepatitis

| • Confirmation of celiac disease by a combination of serologic tests, intestinal biopsy, and clinical response to a gluten-free diet |

| • Abnormal liver tests and/or histological changes in the liver responsive to gluten exclusion |

| • Absence of other chronic liver disease |

Prevalence

Hypertransaminasemia is frequent in untreated CD (sometimes as the sole manifestation), affecting 40% of adults and 60% of children at the time of diagnosis. 4, 6, 7 Conversely, clinical or serological evidence of CD is present in as many of the 9% of persons with chronic unexplained hypertransaminasemia. 8, 9 Celiac patients have both a 2-fold to 6-fold increased risk of later liver disease and 8-fold increased risk of death from liver cirrhosis than the general population.10, 11 Thus, it is possible that a proportion of patients with advanced “cryptogenic” cirrhosis have in fact a chronic liver damage due to unrecognized CD. CD needs to be investigated in all patients with unexplained hypertransaminasemia and/or advanced liver disease.3, 8 The risk of CD is elevated in persons who have a family history of CD, the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) DQ2 or DQ8 alleles, type 1 diabetes mellitus, unexplained iron-deficiency anemia, premature osteoporosis, osteomalacia, autoimmune thyroid disease, Down syndrome, and Turner syndrome. 2, 12

Pathogenesis

The mechanisms underlying celiac hepatitis are poorly understood. Gliadin (a component of gluten) binds to the chemokine receptor (CXCR3) to induce a MyD88-dependent zonulin release that leads to intestinal barrier impairment and increased intestinal permeability in CD. 13 Intestinal permeability (as determined by a lactosemannitol ratio) was quantitatively higher in patients with CD and hypertransaminasemia than in those with CD and normal liver tests.14 Both, intestinal permeability and aminotransferase elevations normalized with the removal of gluten from the diet14; this suggests that dysregulation of the innate and adaptive immune response that is induced by gluten ingestion in genetically-susceptible persons may contribute to celiac hepatitis. Intestinal inflammation and barrier impairment may facilitate the entry to the portal circulation (and then to the liver) of toxins, antigens, cytokines and/or other mediators of liver injury. 6, 9, 15 The biology of these potential mediators of liver injury as well as the possible pathogenic role of celiac-specific autoantibodies remains to be proven,16 however, as liver injury is not commonly seen in other intestinal disorders associated with inflammation and increased intestinal permeability, genetically-driven susceptibility to the toxic effect of gluten exposure or other so far unknown gluten-induced mediators (specific for CD) may play a key role in the pathogenesis of the liver injury associated with CD.

Clinical manifestations

Nonspecific symptoms such as malaise or fatigue are common; however, most patients with celiac hepatitis have no symptoms or signs of liver disease.4, 8 The physical examination is normal in most patients.4, 6-8 Dermatitis herpetiformis may be the only physical clue of CD. The presence of hepatomegaly suggests the coexistence of CD with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.4 Palmar erythema, jaundice, ascites, and splenomegaly may be present when patients with CD have cirrhosis. 5 Other signs of severe hepatic decompensation (e.g., encephalopathy, coagulopathy, or portal hypertension) are extremely rare and may suggest either an alternative diagnosis or the coexistence with other chronic liver disease.3, 4 Mild to moderate (less than 5 times the upper limit of normal) levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and/or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are the most common abnormality. 4, 6, 7, 9 The ratio AST to ALT is usually less than 1.3 Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is uncommon in the absence of cirrhosis.4, 5 Alkaline phosphatase (ALK) may be abnormal in 4% to 20% of the cases and may reflect metabolic bone disease.6 Severe elevations of “hepatic” ALK (up to 5 times the upper limit of normal) with minimal or no elevations of aminotransferases or bilirubin are unusual in celiac hepatitis and may be indicative of infiltrative disorders of the liver (e.g., lymphoma associated with CD) or a primary cholestatic liver disorder. Serum albumin and the prothrombin time are important markers of hepatic synthetic function, but are not specific for liver disease, intestinal inflammation and severe malabsorption may alone be the cause of hypoalbuminemia and prolonged prothrombin time (vitamin K deficiency), that otherwise suggest cirrhosis.12 The ultrasound findings on the liver vary according to the degree of liver injury, from normal to coarse echo texture. 5 A combination of ultrasound signs that have variable positive predictor values, may raise the suspicion of unrecognized CD: dilated small bowel loops, enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, nonocclusive intussusception, increased peristalsis, abnormal jejunum folds, and increased fasting gallbladder volume.17, 18

Histologic findings

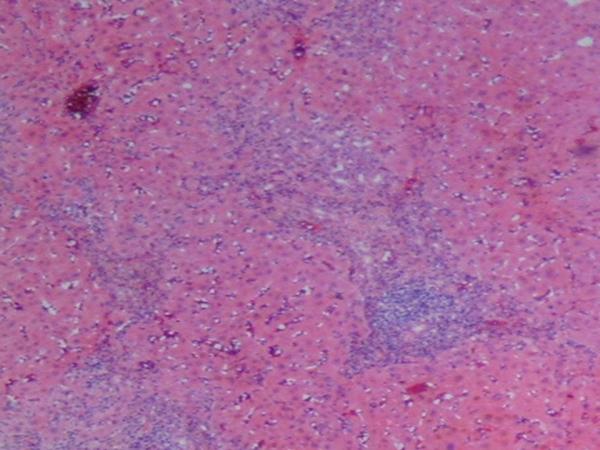

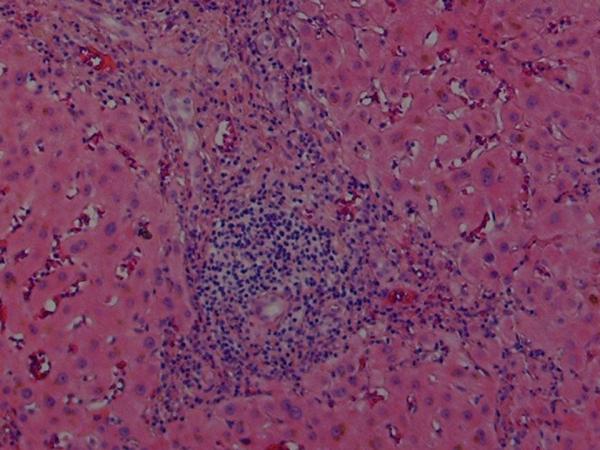

Liver architecture is usually abnormal in celiac hepatitis, but generally the changes are mild and/or nonspecific. 19, 20 Extensive fibrosis and cirrhosis may be late histological changes.5 There is not a pathognomonic histologic finding for celiac hepatitis but the reversible nature of abnormalities after compliance with a GFD is quite characteristic (Table 2). During the pathologic interpretation of the liver biopsy, it is very useful to routinely look for specific findings of other liver disorders that have the potential to be associated with CD and may otherwise remain unrecognized.19, 20 (Figure 1)

Table 2.

Histologic findings in the livers of patients with celiac disease

| • Periportal inflammation |

| • Mononuclear infiltration on the parenchyma |

| • Bile duct obstruction |

| • Hyperplasia of Kupffer cells |

| • Steatosis |

| • Fibrosis (all stages) |

| • Cirrhosis |

Figure 1.

Histologic findings in the liver of a patient with celiac disease and hypertransaminasemia; liver tests returned to normal after 6 months of strict adherence to a gluten-free diet, no follow-up liver biopsy was seem necessary

(A) Low-magnification showing periportal inflammation and mononuclear infiltration on the parenchyma (hematoxylin and eosin)

(B) High-magnification showing the portal triad with extensive mononuclear infiltration. Note the sparing of the biliary ducts (hematoxylin and eosin)

Treatment

Strict GFD is the treatment of choice for celiac hepatitis. Liver tests and histologic changes are expected to revert to normal in most patients with celiac hepatitis after 6-12 months of good adherence to the GFD (Table 3). 4, 6, 7, 19, 21

Table 3.

Prevalence of abnormal liver chemistry test and the effect of a gluten-free diet in patients with celiac disease

| Reference | Cases | Female (n, %) | Age (range) yrs | Abnormal liver test (n, %) | Response to GFD (n, %) | Time on GFD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bardella4 | 158 | 127, 80% | 18-68 | 67, 42% | 60/67, 90% | 6 months |

| Hagander6 | 74 | 43, 58% | 14-73 | 29/53, 55% | N/A* | N/A |

| Bonamico7 | 65 | 43, 66% | 0.5-18 | 37, 60% | N/A | N/A |

| Jacobsen19 | 132 | 64, 48% | 25-86 | 62, 47% | 24/32, 75% | 2 years |

| Dickey21 | 129 | 88, 68% | 17-88 | 17, 13% | 15/17, 88% | 6-12 months |

Transaminase levels fell significantly 2.5-8 wks after starting a GFD

Clinical approach in patients with CD and possible liver injury

Liver tests (especially transaminases) should be routinely checked in all patients with CD at diagnosis.3 The subsequent clinical approach is based on the pattern of the serum liver chemistry abnormalities, the clinical history, and physical findings.

CD and Hypertransaminasemia

The presence of both normal physical examination and hypertransaminasemia < 5 times the upper limit of normal (especially if the ratio AST to ALT is <1) in patients with confirmed CD, strongly suggest celiac hepatitis and no further evaluation to exclude other causes of liver injury is necessary before the evaluation of response to a GFD.3 Liver enzymes should be re-checked after 6-12 months of a strict GFD.3, 21 If the abnormal liver tests return to normal after gluten exclusion, a diagnosis of celiac hepatitis is confirmed, thus, no further investigation is needed and only follow-up is recommended (possibly by physical examination and testing liver tests once a year). The patient will require extended investigation for a concurrent liver disease including specific laboratory and imaging studies (also consider a liver biopsy) to exclude coexistent viral, autoimmune, and metabolic chronic liver disease if: i) persistent hypertransaminasemia after 1 year on strict adherence to a GFD, and ii) transaminases levels >5 times upper limit of normal, physical signs that suggest chronic liver disorder, and/or AST to ALT ratio >1. We favored this “treat-first then re-evaluate” approach instead of initial extensive (and expensive) investigation for other causes of liver disease, because the prevalence of hypertransaminasemia in patients with untreated CD is much higher than the prevalence of the coexistence of primary liver disorder and CD.4, 6, 22

CD and elevated alkaline phosphatase

The first step is to demonstrate the possible origin of the alkaline phosphatase elevation (liver or bone) by measuring gamma glutamyltransferase or 5-nucleotidase levels. If any of those enzymes is abnormal, the patient will require investigation for concurrent liver or systemic disease with secondary infiltration of the liver, especially if intrahepatic cholestasis is present. A very rare cause of obstructive jaundice in patients with CD is biliary tract obstruction secondary to lymphoma.23 If both enzymes are normal, elevated bone alkaline phosphatase is more likely as CD can cause metabolic osteopathy.2 In case of suspicion of osteopathy, measurement of parathormone, calcium, and 25 (OH)-vitamin D are recommended. 12 All patients with recent diagnosis of CD should undergo dual energy x-ray absorptiometry as low bone mass density and osteoporosis have a high prevalence in this population.12 Thyroid dysfunction (more prevalent in CD) may increase the bone fraction of alkaline phosphatase enzyme, thus, the determination of thyroid stimulant hormone maybe useful.12

Role of liver biopsy

Liver biopsy is not recommended in most cases with isolated hypertransaminasemia and CD because of the nonspecific nature of the findings and the high rate of complete response to a GFD.4, 14 Liver biopsy may be useful in the case of: i) Abnormal ALK secondary to intrahepatic cholestasis, ii) persistent hypertransaminasemia after 1-year on strict GFD, iii) coexistent liver disorder in which the liver biopsy has therapeutic or prognostic significance, iv) clinical, serological, or imaging suspicious of coexistent liver disease or malignancy (i.e., liver infiltration by lymphoma). 3

Selected liver disorders associated with celiac disease

Autoimmune Liver Disease

Prevalence

There is good evidence that primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) are associated with CD at a rate greater than that caused by chance alone.3,24, 25 The evidence of association between primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and CD is more tenuous, but has been reported in a small number of case reports.26 The prevalence of CD in patients with PBC or PBC in patients with CD has been extensively studied and varies widely but overall the available evidence strongly support that PBC is associated with CD and vise versa. (Tables 4 and 5) 27, 28,29-31,22, 32-34 CD is present in 4%-6% of patients with both type 1 and type 2 AIH.3, 24, 25, 27

Table 4.

Selected studies on screening of celiac disease in primary biliary cirrhosis

Table 5.

Selected studies on the prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis in patients with celiac disease

Pathogenetic mechanisms

Clinical features common to PBC and CD include an association with other autoimmune diseases, genetic and environmental risk factors, and familial occurrence.2, 35 PBC and CD are both associated with HLA genes, but the genotypes are not the same.35 However, the association may represent a shared susceptibility of biliary and small intestine epithelium to immune-mediated damage.29 CD and PSC share one HLA gene at-risk: DQ2. The presence of HLA-DQ2 is associated with more rapid progression of the liver disease in PSC. 36 Homozygosity for DQ2 is associated with a 5-fold increase in risk for CD and, in some studies, with clinical severity and high-risk of severe complications.37, 38

Effect of gluten-free diet on autoimmune liver disease

Severe steatorrhea and other symptoms attributable to CD improved with GFD in patients with autoimmune liver disease; however, the liver blood tests or liver-related symptoms were not affected despite good adherence to GFD as suggested by the disappearance of the endomysial antibody in serum. 25, 28 Large prospective studies are needed to further evaluate the effect (if any) of gluten exclusion in the rate of histologic remission, liver transplantation, and liver-related mortality in patients with both CD and autoimmune liver disease.

Viral Hepatitis

The prevalence of CD in patients with chronic hepatitis C has been reported to be around 1.2%. 39 A well-defined route of transmission for hepatitis C was found in most patients having both CD and hepatitis C in a recent study, this suggest a spurious association of hepatitis C and CD.40 Thus, clear association of CD and chronic hepatitis C is lacking. However, hepatitis C treatment with interferon-α and/or ribavirin may activate silent or latent CD, usually after 2-5 months after the onset of antiviral therapy.3 Thus, CD should be investigated in patients with hepatitis C and unexplained diarrhea, marked weight loss, and/or celiac serology seroconversion after treatment with antivirals. 41, 42 The rate of hepatitis B vaccine non-response in children and adult patients with CD was 54% and 68%, respectively.43, 44 Gluten intake may interfere with the humoral response to the hepatitis B vaccine, as the rate of seroconversion correlated with the amount of gluten ingestion and >95% of patients vaccinated after treatment with a gluten-free diet may respond irrespective of the HLA-DQ2 haplotype.45 However, HLA-DQ2 itself may be important factor of non-response in some patients.43, 46

Liver Transplantation and Celiac Disease

The prevalence of CD in patients with end-stage liver disease whom underwent liver transplantation has been reported to be between 3%-4.3%.5, 47 In a small number of patients listed for liver transplantation because end-stage liver disease, the strict adherence for 6 months to a GFD improved patient symptoms, liver chemistries, and indirect markers of hepatic synthetic function to a level that make liver transplant unnecesary.5 However, the beneficial effect of a GFD in patients with end-stage liver disease requires further clarification by large, controlled, prospective randomized trials. Both, celiac serology (EMA and tTGA) and CD-associated symptoms may disappear or improve after liver transplantation without gluten exclusion in patients with autoimmune liver disorders and coexistent CD; however the risk of severe complications such as lymphoma is a concern. 47 The post-transplantation suppression of tTGA and EMA antibodies suggest that negative celiac serology after liver transplantation cannot exclude a diagnosis of CD and support the need of pre-transplantation screening in patients with end-stage autoimmune liver disease (especially if HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 positive).48

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

The prevalence of CD in patients with NAFLD has been reported to be around 3%.49 The gluten-free diet may improve liver tests in patients with NAFLD, but it effect (if any) in the long-term outcome of NAFLD is unknown.49

Diagnosis of celiac disease in patients with chronic liver disorders

Serologic tests

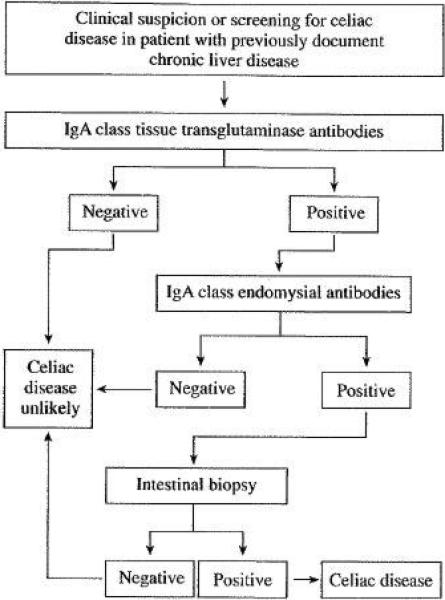

The most sensitive antibody tests for the diagnosis of CD are of the IgA class2, however, the interpretation of celiac serologic tests in patients with chronic liver disorders deserves special attention because their accuracy is significantly lower than in the general population. The anti-gliadin antibody is not longer recommended for the diagnosis of CD because low diagnostic accuracy and the availability of new generation tests. 12 The clinical utility of anti-gliadin antibodies in patients with chronic liver disease is especially poor because of frequent false positive result (~20%) secondary to increased permeability of the gut to food antigens (including gluten). 50 Tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTGA) tests are the most frequent used antibodies for the diagnosis of CD and may use tissue transglutaminase antigen derived form guinea pig or human (generated from human erythrocytes or recombinantly).12 Although still useful in patients with chronic liver disease, the rate of false positive result is higher than in the general population, especially for guinea pig substrate.51,52 There is a positive correlation between false positive result and the degree of liver fibrosis. 53 Therefore, a cautious interpretation of the tTGA result is necessary especially in patients with advanced liver fibrosis.51, 53, 54 Finally, the endomysial antibody (EMA) is detected by indirect immunofluorescence assay in both monkey esophagus and/or umbilical cord. 12 This antibody is less sensitive than the tTGA IgA but appears to have a very high specificity for CD (>99%) even in the presence of advanced chronic liver disease. 51, 53, 54 Thus, EMA is the serologic test with higher specificity for the diagnosis of CD in patients with chronic liver disease, however, as tTGA have a better sensitivity than EMA, which is technically challenging to perform, a sequential testing paradigm using subsequent EMA test for every positive tTGA result may increase the overall diagnostic accuracy in patients with chronic liver disease (Figure 2). While is expected that GFD normalizes CD serology2, a recent study demonstrated that immunosuppression and/or liver transplantation in the absence of gluten withdrawal normalizes both tTGA and EMA in patients with autoimmune liver diseases and pretransplantation positive celiac serology (either tTGA or EMA). This suppression of antibody response is important when testing for CD after organ transplantation.47 The accuracy of celiac serologic tests is also affected by: 1) the increased prevalence of selective IgA deficiency in CD that makes IgA class-based tests unreliable, 2) the degree of intestinal damage (lower sensitivity with lesser degrees of villous atrophy), and 3) the onset of a gluten-free diet prior to serologic screening. 2, 12

Figure 2.

Suggested approach to the diagnosis of celiac disease in patients with chronic liver disease

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping

The alleles that codify for HLA-DQ2 are present in >90% of patients with CD, and those for HLA-DQ8 in the remaining cases. 12 Thus, the absence of CD-associated HLA genes DQ2 or DQ8 makes CD very unlikely. The prevalence of both tTGA and EMA was higher in patients with both end-stage autoimmune liver disease and the HLADQ2 or DQ8 alleles than in those patients without those HLA-genotypes, suggesting that HLA status may be useful to predict risk of CD in patients with end-stage autoimmune liver disease.47 HLA-genotyping may be also useful in patients with non-concordant results among serology and intestinal biopsy or those with a questionable diagnosis.2

Intestinal Biopsy

Intestinal biopsy is the gold standard for CD diagnosis. 12 Positive serology needs to be confirmed by intestinal biopsy showing the classic histologic features of increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, crypt hyperplasia, and villous atrophy (summarized in the Marsh classification).55 Subsequently, the patient should have a positive response to a gluten-free diet.2 Response to a gluten-free diet in subjects without both supportive serologic test and biopsy is not an indicator of CD as clinical response to a GFD can be observed in other gastrointestinal disorders such as diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome.56

Conclusions

Celiac disease interacts with the liver by either cause injury itself or by modulates the impact of other disorders of the liver when they coexist. The liver injury in CD has a wide spectrum ranging from asymptomatic elevation of liver chemistries to severe liver failure. Celiac hepatitis is the most common “hepatic” presentation of CD and gluten exclusion is the treatment of choice. The prevalence of CD is higher in patients with several chronic liver disorders than the prevalence found in the general population but an association has been clearly demonstrated epidemiologically in a few primarily immune-mediated liver disorders. Clinicians need to be aware of these associations of CD to improve detection rate of CD in patients with those liver diseases. The diagnosis of CD in patients with chronic liver disorders is complicated by the low diagnostic accuracy of most serologic tests than in subjects without liver disease. Larger, prospective, and probably multicenter, randomized trials are needed to clarify the effect of a GFD in the long-term outcome of liver disorders that may coexist with CD.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award/Training Grant in Gastrointestinal Allergy and Immunology (T32 AI-07047) (to ART) and the NIH grants DK-57892 and DK-070031 (to JAM).

Abbreviations

- ALK

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CD

celiac disease

- EMA

endomysial antibodies

- GFD

gluten-free diet

- tTGA

tissue transglutaminase antibodies

Footnotes

Authors declare no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Catassi C. The world map of celiac disease. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2005;35:37–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1731–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. The liver in celiac disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:1650–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardella MT, Fraquelli M, Quatrini M, Molteni N, Bianchi P, Conte D. Prevalence of hypertransaminasemia in adult celiac patients and effect of gluten-free diet. Hepatology. 1995;22:833–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaukinen K, Halme L, Collin P, Farkkila M, Maki M, Vehmanen P, Partanen J, Hockerstedt K. Celiac disease in patients with severe liver disease: gluten-free diet may reverse hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:881–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagander B, Berg NO, Brandt L, Norden A, Sjolund K, Stenstam M. Hepatic injury in adult coeliac disease. Lancet. 1977;2:270–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonamico M, Pitzalis G, Culasso F, Vania A, Monti S, Benedetti C, Mariani P, Signoretti A. [Hepatic damage in celiac disease in children]. Minerva Pediatr. 1986;38:959–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardella MT, Vecchi M, Conte D, Del Ninno E, Fraquelli M, Pacchetti S, Minola E, Landoni M, Cesana BM, De Franchis R. Chronic unexplained hypertransaminasemia may be caused by occult celiac disease. Hepatology. 1999;29:654–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volta U, De Franceschi L, Lari F, Molinaro N, Zoli M, Bianchi FB. Coeliac disease hidden by cryptogenic hypertransaminasaemia. Lancet. 1998;352:26–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludvigsson JF, Elfstrom P, Broome U, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Celiac disease and risk of liver disease: a general population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:63–69. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters U, Askling J, Gridley G, Ekbom A, Linet M. Causes of death in patients with celiac disease in a population-based Swedish cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1566–72. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.13.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1981–2002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lammers KM, Lu R, Brownley J, Lu B, Gerard C, Thomas K, Rallabhandi P, Shea-Donohue T, Tamiz A, Alkan S, Netzel-Arnett S, Antalis T, Vogel SN, Fasano A. Gliadin induces an increase in intestinal permeability and zonulin release by binding to the chemokine receptor CXCR3. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:194–204. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novacek G, Miehsler W, Wrba F, Ferenci P, Penner E, Vogelsang H. Prevalence and clinical importance of hypertransaminasaemia in coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:283–8. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199903000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelaez-Luna M, Schmulson M, Robles-Diaz G. Intestinal involvement is not sufficient to explain hypertransaminasemia in celiac disease? Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:937–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korponay-Szabo IR, Halttunen T, Szalai Z, Laurila K, Kiraly R, Kovacs JB, Fesus L, Maki M. In vivo targeting of intestinal and extraintestinal transglutaminase 2 by coeliac autoantibodies. Gut. 2004;53:641–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraquelli M, Colli A, Colucci A, Bardella MT, Trovato C, Pometta R, Pagliarulo M, Conte D. Accuracy of ultrasonography in predicting celiac disease. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:169–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rettenbacher T, Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, Huber S, Gritzmann N. Adult celiac disease: US signs. Radiology. 1999;211:389–94. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma39389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen MB, Fausa O, Elgjo K, Schrumpf E. Hepatic lesions in adult coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:656–62. doi: 10.3109/00365529008997589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollock DJ. The liver in coeliac disease. Histopathology. 1977;1:421–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1977.tb01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dickey W, McMillan SA, Collins JS, Watson RG, McLoughlin JC, Love AH. Liver abnormalities associated with celiac sprue. How common are they, what is their significance, and what do we do about them? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:290–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawson A, West J, Aithal GP, Logan RF. Autoimmune cholestatic liver disease in people with coeliac disease: a population-based study of their association. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:401–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buess M, Steuerwald M, Wegmann W, Rothen M. Obstructive jaundice caused by enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in a patient with celiac sprue. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1110–3. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1453-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volta U, De Franceschi L, Molinaro N, Cassani F, Muratori L, Lenzi M, Bianchi FB, Czaja AJ. Frequency and significance of anti-gliadin and anti-endomysial antibodies in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2190–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1026650118759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villalta D, Girolami D, Bidoli E, Bizzaro N, Tampoia M, Liguori M, Pradella M, Tonutti E, Tozzoli R. High prevalence of celiac disease in autoimmune hepatitis detected by anti-tissue tranglutaminase autoantibodies. J Clin Lab Anal. 2005;19:6–10. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hay JE, Wiesner RH, Shorter RG, LaRusso NF, Baldus WP. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and celiac disease. A novel association. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:713–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-9-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volta U, Rodrigo L, Granito A, Petrolini N, Muratori P, Muratori L, Linares A, Veronesi L, Fuentes D, Zauli D, Bianchi FB. Celiac disease in autoimmune cholestatic liver disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2609–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickey W, McMillan SA, Callender ME. High prevalence of celiac sprue among patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:328–9. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199707000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kingham JG, Parker DR. The association between primary biliary cirrhosis and coeliac disease: a study of relative prevalences. Gut. 1998;42:120–2. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.1.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niveloni S, Dezi R, Pedreira S, Podesta A, Cabanne A, Vazquez H, Sugai E, Smecuol E, Doldan I, Valero J, Kogan Z, Boerr L, Maurino E, Terg R, Bai JC. Gluten sensitivity in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:404–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Floreani A, Betterle C, Baragiotta A, Martini S, Venturi C, Basso D, Pittoni M, Chiarelli S, Sategna Guidetti C. Prevalence of coeliac disease in primary biliary cirrhosis and of antimitochondrial antibodies in adult coeliac disease patients in Italy. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34:258–61. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)80145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillett HR, Cauch-Dudek K, Jenny E, Heathcote EJ, Freeman HJ. Prevalence of IgA antibodies to endomysium and tissue transglutaminase in primary biliary cirrhosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14:672–5. doi: 10.1155/2000/934709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bardella MT, Quatrini M, Zuin M, Podda M, Cesarini L, Velio P, Bianchi P, Conte D. Screening patients with celiac disease for primary biliary cirrhosis and vice versa. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1524–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorensen HT, Thulstrup AM, Blomqvist P, Norgaard B, Fonager K, Ekbom A. Risk of primary biliary liver cirrhosis in patients with coeliac disease: Danish and Swedish cohort data. Gut. 1999;44:736–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.5.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1261–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boberg KM, Spurkland A, Rocca G, Egeland T, Saarinen S, Mitchell S, Broome U, Chapman R, Olerup O, Pares A, Rosina F, Schrumpf E. The HLA-DR3,DQ2 heterozygous genotype is associated with an accelerated progression of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:886–90. doi: 10.1080/003655201750313441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray JA, Moore SB, Van Dyke CT, Lahr BD, Dierkhising RA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, 3rd, Kroning CM, El-Yousseff M, Czaja AJ. HLA DQ gene dosage and risk and severity of celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1406–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Toma A, Goerres MS, Meijer JW, Pena AS, Crusius JB, Mulder CJ. Human leukocyte antigen-DQ2 homozygosity and the development of refractory celiac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fine KD, Ogunji F, Saloum Y, Beharry S, Crippin J, Weinstein J. Celiac sprue: another autoimmune syndrome associated with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:138–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thevenot T, Boruchowicz A, Henrion J, Nalet B, Moindrot H. Celiac disease is not associated with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1310–2. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bardella MT, Marino R, Meroni PL. Celiac disease during interferon treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:157–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adinolfi LE, Durante Mangoni E, Andreana A. Interferon and ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis C may activate celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:607–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noh KW, Poland GA, Murray JA. Hepatitis B vaccine nonresponse and celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2289–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park SD, Markowitz J, Pettei M, Weinstein T, Sison CP, Swiss SR, Levine J. Failure to respond to hepatitis B vaccine in children with celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:431–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3180320654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nemes E, Lefler E, Szegedi L, Kapitany A, Kovacs JB, Balogh M, Szabados K, Tumpek J, Sipka S, Korponay-Szabo IR. Gluten intake interferes with the humoral immune response to recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in patients with celiac disease. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1570–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craven DE, Awdeh ZL, Kunches LM, Yunis EJ, Dienstag JL, Werner BG, Polk BF, Syndman DR, Platt R, Crumpacker CS, et al. Nonresponsiveness to hepatitis B vaccine in health care workers. Results of revaccination and genetic typings. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:356–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-3-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubio-Tapia A, Abdulkarim AS, Wiesner RH, Moore SB, Krause PK, Murray JA. Celiac disease autoantibodies in severe autoimmune liver disease and the effect of liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2008;28:467–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dalekos GN, Bogdanos DP, Neuberger J. Celiac disease-related autoantibodies in end-stage autoimmune liver diseases: what is the message? Liver Int. 2008;28:426–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bardella MT, Valenti L, Pagliari C, Peracchi M, Fare M, Fracanzani AL, Fargion S. Searching for coeliac disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:333–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sjoberg K, Lindgren S, Eriksson S. Frequent occurrence of non-specific gliadin antibodies in chronic liver disease. Endomysial but not gliadin antibodies predict coeliac disease in patients with chronic liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:1162–7. doi: 10.3109/00365529709002997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carroccio A, Giannitrapani L, Soresi M, Not T, Iacono G, Di Rosa C, Panfili E, Notarbartolo A, Montalto G. Guinea pig transglutaminase immunolinked assay does not predict coeliac disease in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 2001;49:506–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.4.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bizzaro N, Tampoia M, Villalta D, Platzgummer S, Liguori M, Tozzoli R, Tonutti E. Low specificity of anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2006;20:184–9. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vecchi M, Folli C, Donato MF, Formenti S, Arosio E, de Franchis R. High rate of positive anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in chronic liver disease. Role of liver decompensation and of the antigen source. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:50–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villalta D, Crovatto M, Stella S, Tonutti E, Tozzoli R, Bizzaro N. False positive reactions for IgA and IgG anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in liver cirrhosis are common and method-dependent. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;356:102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (‘celiac sprue’). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wahnschaffe U, Schulzke JD, Zeitz M, Ullrich R. Predictors of clinical response to gluten-free diet in patients diagnosed with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:844–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.03.021. quiz 769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]