ABSTRACT

Purpose: To explore the perspectives of leading advocates regarding the attributes required for excelling in the advocate role as described within the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada (2009). Methods: We used a descriptive qualitative design involving in-depth, semi-structured interviews conducted with leading Canadian advocates within the physiotherapy profession. Transcribed interviews were coded and analyzed using thematic analysis. Results: The 17 participants identified eight attributes necessary for excelling in the role of advocate: collaboration, communication, scholarly practice, management, professionalism, passion, perseverance, and humility. The first five attributes correspond to roles within the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada. Participants identified the attributes of collaboration, communication, and scholarly practice as the most important for successful advocacy. Participants also noted that the eight identified attributes must be used together and tailored to meet the needs of the advocacy setting. Conclusions: Identifying these eight attributes is an important first step in understanding how competence in the advocate role can be developed among physiotherapy students and practitioners. Most importantly, this study contributes to the knowledge base that helps physiotherapists to excel in advocating for their clients and the profession.

Key Words: competency-based education, patient advocacy, professional competence

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif: Étudier les points de vue des principaux défenseurs au sujet des qualités requises pour exceller dans le rôle de défenseur décrit dans le Profil des compétences essentielles des physiothérapeutes au Canada (2009). Méthodes: Nous avons utilisé un contexte qualitatif descriptif comportant des entrevues semi-structurées détaillées réalisées auprès de défenseurs canadiens de premier plan de la profession. Nous avons codé les entrevues transcrites et les avons analysées en appliquant une analyse thématique. Résultats: Les 17 participants ont défini huit qualités nécessaires pour exceller dans le rôle de défenseur: collaboration, communication, pratique savante, gestion, professionnalisme, passion, persévérance et humilité. Les cinq premières qualités correspondent aux rôles décrits dans le Profil des compétences essentielles des physiothérapeutes au Canada. Les participants ont considéré la collaboration, la communication et la pratique savante comme les qualités les plus importantes pour réussir comme défenseur. Ils ont aussi signalé que les huit qualités définies doivent servir ensemble et être personnalisées de façon à répondre aux besoins du contexte de défense. Conclusion: La détermination de ces huit qualités constitue une première étape importante pour comprendre comment les étudiants en physiothérapie et les praticiens peuvent devenir défenseurs compétents. Le plus important: cette étude contribue à la base de savoir qui aide les physiothérapeutes à exceller dans la défense de leurs clients et de la profession.

Mots clés : spécialité de la physiothérapie, compétence professionnelle; éducation basée sur les compétences; défense des patients

The Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada (ECP) was released in October 2009 by the National Physiotherapy Advisory Group and was based on the long-standing Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) framework developed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.1,2 The ECP was developed to describe the seven essential competencies required of physiotherapists as they begin their professional practice and throughout their careers. The competencies are organized into seven roles: the central, integrative role of expert and the roles of collaborator, communicator, manager, scholarly practitioner, professional, and advocate.1 The advocate role is further described as follows: “physiotherapists responsibly use their knowledge and expertise to promote the health and well-being of individual clients, communities, populations and the profession.”1(p.5) The importance of advocacy in the physiotherapy profession is highlighted by its inclusion in the ECP. In addition, several provincial regulatory bodies have indicated the importance of physiotherapists advocating for the needs of their clients and on behalf of the profession.3,4 Despite the importance of this role, however, little is known about how it might be understood and developed within physiotherapy.

Other health disciplines, including medicine, nursing, and occupational therapy also identify the advocate role as a core competency within their own professions.2,5,6 The literature on the advocate role in these professions focuses primarily on describing teaching strategies for the development of this role among professional students and practitioners, such as student advocacy initiatives, service-based learning, and collaborating with community organizations.7–9 There is debate in the nursing literature about whether the advocate role should be taught through formal education or learned through practical experience.10,11 Dhillon and colleagues found that, among occupational therapists, the advocate role is developed mainly through observation, experience, and reflective practice rather than through formal education.12 Across health care disciplines, the advocate role is central, but general approaches to developing advocacy remain variable. In 2008, Flynn and Verma broadened the literature on health advocacy by investigating specific attributes that are fundamental for health advocacy among medical students.13 They found that the health advocate role is often lost among the competing responsibilities of medical practitioners; by identifying key attributes necessary for success in this role, however, educators may be better able to build a curriculum that effectively develops and evaluates advocacy competency among medical students.13

There has been little research in physiotherapy on which attributes are important for excelling in the role of advocate, how competence in these attributes should be evaluated, and how the advocate role should be developed among professional students and practitioners. As a first step toward addressing these gaps, our goal in this study was to explore what attributes leading Canadian advocates within the physiotherapy profession consider crucial for excelling in the advocate role.

Methods

Participants

Our study used a descriptive qualitative design to allow participants to share their views on the advocate role through interviews that preserved both their words and their intended meanings.14 The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto. We recruited English-speaking participants who self-identified as meeting the following inclusion criteria: (a) Has volunteered or worked in Canada for at least 1 year as an advocate; (b) is viewed as a “leading advocate,” defined as an individual who (i) is considered a leader in promoting the health and well-being of clients, and/or communities, and/or populations, and/or the profession, and (ii) is passionate, vocal, and driven toward mobilizing change in the health care system and/or empowering others to pursue their health-related goals; and (c) has knowledge of the workings of physiotherapy departments in Canadian universities.

In addition to these criteria, we sought diversity across a range of experiences relevant to the research question. First, we aimed to recruit at least one participant from each of the following regions in Canada: Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island), Quebec, Ontario, Prairies (Manitoba, Saskatchewan), and Western Canada (Alberta, British Columbia); we also purposively sought participants with advocacy experience in rural parts of Canada. Second, we sought to recruit at least one participant with experience in each of the advocacy levels identified in the ECP: advocacy for individuals, communities, populations, and the profession. Third, we sought to recruit at least one participant each with experience in four main areas of physiotherapy: clinical practice, education, research, and policy.

Sampling and recruitment

We recruited participants via a combination of purposive and snowball sampling techniques. After generating a list of potential participants from known contacts of the research team, members of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA) Leadership Division, recipients of the Enid Graham Memorial Lecture award (CPA's top award), and keynote speakers from past CPA conferences, we sent a recruitment letter by email. Interested participants who responded were then contacted to schedule a time and date for an interview. A follow-up letter was sent by email to those who did not respond to the recruitment letter after one week. We also asked participants to refer other potential participants to the study (snowball sampling).

Data collection

The research team created an interview guide based on the goals of the study and pilot tested it with two participants who met the inclusion criteria for the study but were not included in the final sample. As a result of the pilot testing, we revised the original interview guide and created a final version (see Box 1). Participants chose whether their interview would be conducted face-to-face, by video (Skype), or by telephone. Before each interview, participants received a consent form via email. For face-to-face interviews, participants returned a signed copy of the consent form on the day of the interview; for Skype and telephone interviews, verbal consent was documented on the day of the interview. In-depth, semi-structured one-on-one interviews, each 30–60 minutes in duration, were conducted with each participant by one of two researchers (KK, EH). All interviews were audio recorded for transcription purposes.

Box 1. Components of the Interview Guide.

Section I: Demographic information

Professional designation

Age

Years of practice

- Areas of practice

- Clinical practice

- Education

- Research

- Policy

- Experience in advocacy

- Individual level

- Community level

- Population level

- Professional level

- Regional representation

- Atlantic Canada

- Quebec

- Ontario

- Prairies

- Western Canada

- Rural Canada

Section II: Experiences in advocacy

- Clinical practice

- What is your experience in clinical practice?

- How does advocacy play out in your clinical practice setting?

- What attributes have enabled you to be a successful advocate in this setting?

- Education

- What is your experience in education?

- How does advocacy play out within an education setting?

- What attributes have enabled you to be a successful advocate in this setting?

- Research

- What is your experience in research?

- How does advocacy play out in a research setting?

- What attributes have enabled you to be a successful advocate in this setting?

- Policy

- What is your experience in policy?

- How does advocacy play out in a policy setting?

- What attributes have enabled you to be a successful advocate in this setting?

Data analysis

The data analysis process was adapted from the thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke.15 Following the interviews, the audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by members of the research team who were not involved in conducting the interviews (MM, JY); transcriptions were then quality checked by the interviewer to ensure accuracy and completeness. Quality-checked transcripts were uploaded to a password protected website. Each member of the research team read several transcripts and identified recurrent ideas in the data. These insights were used to develop a preliminary coding scheme, which was pilot tested on a sample of transcripts. A final coding scheme was established based on dialogue among members of the research team following the initial application of the preliminary coding scheme. Each transcript was coded by two team members. Once coded, transcripts were uploaded to the qualitative analysis software NVivo 10 (QSR International, Burlington, Massachusetts) and a node report that identified and aggregated all coded data for a given code was generated for each code.16 The node report for each code was summarized by a member of the research team, who then met to discuss each of these summaries. During these discussions, the team identified themes within and across codes to address the research question.

Results

Participants

The 13 women and 4 men recruited to the study were all physiotherapists; one was retired. They had practised for an average of 27 (range 5–43) years. The participants satisfied the sampling criteria of regional representation, levels of advocacy, and areas of practice (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n=17)

| Characteristic | No (%) of participants |

|---|---|

| Geographic region* | |

| Atlantic Canada | 2 (12) |

| Quebec | 5 (29) |

| Ontario | 10 (59) |

| Prairies | 3 (18) |

| Western Canada | 4 (24) |

| Rural Canada | 5 (29) |

| Level of advocacy* | |

| Individual | 17 (100) |

| Community | 12 (71) |

| Population | 11 (65) |

| Professional | 15 (88) |

| Area of practice* | |

| Clinical practice | 17 (100) |

| Education | 14 (82) |

| Research | 13 (76) |

| Policy | 10 (59) |

Participants were asked to select all that applied. For geographic region, participants were asked to select regions they were from or in which they had experience. Therefore, percentages add to >100%.

Attributes deemed crucial for advocacy

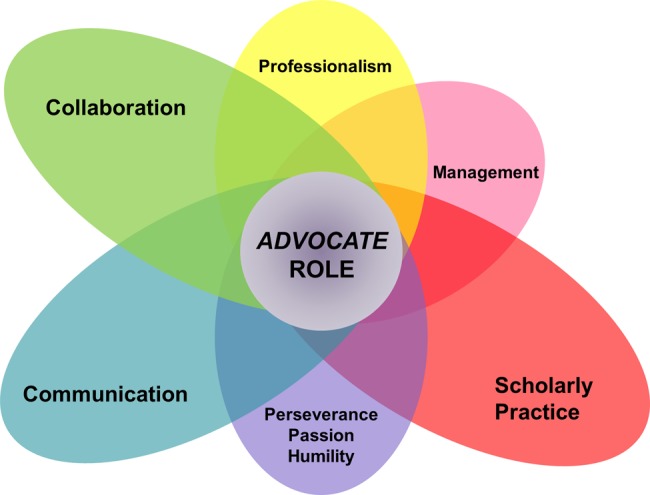

Participants were asked to discuss their experiences with advocacy and consider the attributes necessary for successful advocacy within the physiotherapy profession. Participants told us that to be successful in the advocate role, physiotherapists must be able to draw on, integrate, and execute eight key attributes (illustrated in Figure 1 using a graphical representation based on the CanMEDS framework2). Five of the attributes identified are existing ECP roles: collaboration, communication, scholarly practice, management, and professionalism. The three additional attributes are passion, perseverance, and humility.

Figure 1.

Eight attributes required for success in the advocate role: five that parallel roles from the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada and three additional attributes. Larger petals indicate the attributes identified by participants as most important to the advocate role.

ECP roles

Of the five identified attributes that correspond with ECP roles, collaboration, communication, and scholarly practice were identified by participants as particularly important for success in advocacy.

Collaboration

Participants suggested that collaboration is an essential attribute for advocacy, in which success relies on collaborating with multiple people in various ways. Participant 9 noted the importance of collaborating with others to increase the strength of one's message: “The greater number of people you represent, the greater argument you're going to have.” Participant 10 highlighted the importance of understanding the roles of other health care professionals so as to collaborate and best meet the needs of clients:

Have a good understanding of what a physio's role is and the type of advocacy we can have for our patients … have an understanding of … when other professionals can help fulfill that need, then we can help fill the void that way and liaise with other professions to figure out what will be best for that patient.

Participants also suggested that effective collaboration requires strong communication skills and strategic partnership building. Participant 3 noted the importance of “joining with those individuals that are going about the approach in exactly the same way … people who share the same values around how to move forward in the advocacy agenda versus aligning with just anybody.”

Communication

Closely related to collaboration is the attribute of communication. Many participants highlighted the relationship between collaboration and exceptional communication skills. Participant 2 noted the importance of communicating “with leaders who are in the moment, who have accountability for driving that strategy.” Participants noted that knowing one's audience and tailoring one's communication style accordingly is critical:

You have to know the lay of the land and the language of those who you are talking to … it's getting your language right and between all those groups making sure you have a consistent message.

(Participant 4)

Some participants emphasized the importance of speaking out, while others discussed the importance of being a good listener. Being a good listener was described as crucial to understanding the needs of others and as an important first step in empowering clients to advocate for themselves. Participant 4 emphasized that physiotherapists need to “teach [clients] how to get out there and do it for themselves, advocate for themselves, because that is a skill that they can take lifelong.”

Scholarly practice

Along with collaboration and communication, participants identified the attribute of scholarly practice as an essential skill for successful advocacy. Participants highlighted the need to understand the context in which one is advocating: “[One must have a] knowledge of the people that you're working with … what their mandate is and what their mission is” (Participant 5). Participants suggested that, before speaking out, one needs to have sufficient data and research to support the argument. Participant 11 stated, “If you can't demonstrate that there's a need, then nobody is going to listen to you”; Participant 2 said, “[We must] do the research, and have the findings, and then advocate that patients get the kind of treatment … [that] we have found from our research to be effective.”

Management and professionalism

The attributes of management and professionalism were also viewed as important for advocacy but to a lesser extent than collaboration, communication, and scholarly practice. Participants identified the importance of understanding aspects of practice in relation to management and how these factors affect one's ability to advocate for clients. Participant 3 emphasized the importance of being aware of this issue:

[There are] financial and funding factors and service delivery model factors that impact [physiotherapists'] ability to work with … and advocate on behalf of their patients. And I think bringing an awareness around how [these] factors impact their ability to manage their practices effectively and advocate for themselves … is critical to their understanding.

Participants also recognized the importance of professionalism and engaging in roles beyond that of clinician. They saw professionalism as a commitment to acting in the client's best interests. Participant 15 broadly described professionalism in advocacy as

showing a commitment not as much to your profession and not necessarily a commitment to providing a service to get paid, but showing a commitment to improving the quality of health care that Canadians are receiving.

Additional attributes

In addition to the five ECP competencies identified by participants as necessary attributes for success in the advocate role, participants identified three additional attributes: passion, perseverance, and humility (see Figure 1).

Passion

Participants saw passion as an essential part of advocacy. Participant 2 identified passion as “the number one thing about advocacy … [when you feel] passionate enough about whatever the issue, then advocacy becomes a lot easier.” However, not all participants agreed on the importance of strong emotions. Participant 4 warned that while passion is an important component of advocacy, emotions need to be kept in check: “There's a place for passion in an advocacy argument … there's no place for anger.”

Perseverance

Perseverance was commonly identified by participants as important for successful advocacy. Participants stressed that being an advocate is often a long-term endeavour, and perseverance is, therefore, essential to success. Participant 16 noted that those who engage in advocacy “[demonstrate] a great deal of perseverance … They [need] to work and keep working at the process.” Some participants further noted that there is a certain attitudinal change that often must accompany perseverance. Participant 10 described the importance of being “stubborn” and committed to one's advocacy aims:

[Physiotherapists] don't like to brag and … talk about how good we are and … how important a part we are in the team. I think we need to be a bit more stubborn and need to be a bit more boastful on how good we are.

Humility

Lastly, participants identified the role of humility, which Participant 9 described as “[a willingness] to not be in the limelight.” Others recognized that humility involves being able to reflect on whose agenda is being put forward and commit to advocating for an agenda other than one's own:

There are risks associated with [advocating for others] in terms of the degree to which we really understand the needs and priorities of other people. So a great deal of reflexivity … thinking about the ways we might be imposing our own priorities, goals, etcetera on other people [is needed].

(Participant 16)

Discussion

Advocacy attributes among health care professionals

This is the first study to explore the attributes required to excel in the advocate role in physiotherapy. Overall, we found that success in the advocate role requires competence in eight attributes: collaboration, communication, scholarly practice, management, professionalism, passion, perseverance, and humility. While all attributes were deemed important by participants, collaboration, communication, and scholarly practice were seen as most important. The importance of collaboration and communication has also been identified in the nursing literature. In 2010, Hanks found that the most common descriptions of nurse advocacy included competence in collaboration and communication skills.17 In 2008, Flynn and Verma identified six fundamental attributes required for success in the health advocate role within the CanMEDS framework: knowledgeable, altruistic, honest, assertive, resourceful, and up-to-date.13 The authors compared these attributes to the existing roles in the CanMEDS framework and highlighted their alignment with the roles of expert, professional, communicator, collaborator, manager, and scholarly practitioner, respectively.14 Flynn and Verma's findings are consistent with our results, which show that the attributes necessary for success in the advocate role include the other existing roles within the physiotherapy competency framework, the ECP. While we did not set out expecting the key attributes necessary for success in advocacy to be roles already identified in the ECP, the congruence between our findings and an existing fundamental document for the physiotherapy profession is encouraging.

In addition to the roles outlined in the ECP, we identified three additional attributes required for success in the advocate role: passion, perseverance, and humility. The importance of these attributes is echoed in the medicine, nursing, and occupational therapy literature on health advocacy, which have all discussed the importance of concepts related to passion, perseverance, and humility.8,13,17,18 For example, Vaartio and colleagues portrayed the importance of passion in nursing advocacy by indicating the need for whistle-blowing activities that draw attention to patients' rights and needs18 and highlighted the importance of perseverance by describing the advocacy process as an often lengthy endeavour.18 Flynn and Verma have further discussed the importance of humility among medical residents, noting that being honest, knowing one's limits, disclosing errors, and having realistic expectations are desirable behaviours for successful health advocacy.13

A framework for understanding the advocate role

Our results suggest that success in the advocate role requires an ability to integrate and tailor several attributes specific to the advocacy setting. This idea of integration has already been used to describe the expert role in the ECP framework1 demonstrating that expert physiotherapy practice requires drawing on and integrating the other six roles. We propose that, much like the expert role, success in the advocate role requires the ability to draw on and integrate the attributes of collaboration, communication, scholarly practice, management, professionalism, passion, perseverance, and humility (see Figure 1). Flynn and Verma have proposed that the health advocate role incorporates several attributes that correspond to the roles outlined in the CanMEDS framework13; the health advocate role can be seen as a set of building blocks, the foundational blocks being the other CanMEDS roles that would support the top block—the advocate role.13 However, we propose that the advocate role be viewed not as a separate top building block but, instead, as the centrepiece of an integration of fundamental attributes. The integration of each attribute is required for success in advocacy, and some attributes are particularly essential, depending on the advocacy context.

Implications for practice

Our findings have numerous implications for physiotherapy education and practice. An understanding of the attributes required for success in the advocate role, as well as the model of the advocate role outlined here, could provide a novel approach to developing and evaluating this role among professional students and practitioners. Our study highlights the fact that the ECP roles should not be considered and targeted independently but, rather, should be integrated in the development of advocacy skills. Furthermore, an evaluation of competence in the advocate role should also complement this new model. Evaluation of competence in the advocate role among professional students and practitioners could focus on measuring the eight attributes outlined above as well as the ability to integrate these attributes and tailor them appropriately to the context.

Our study has several limitations. First, while the research team provided participants with the ECP definition of the advocate role, the term advocacy was not defined, and thus participants' perceptions of advocacy may have differed. Furthermore, the four levels of advocacy identified in the ECP (i.e., advocacy for individuals, communities, populations and the profession) are not defined, and participants' understandings of these terms may also have varied. However, by allowing participants to discuss their experiences in advocacy without providing a strict definition of the term, we were able to collect diverse and rich perspectives on multiple meanings of advocacy. Second, participants had an average of 27 years' experience in practice; the study did not explore the experiences and perspectives of students and recent graduates. Third, only physiotherapists were included in the study to capture the perspectives of key stakeholders in advancing the advocate role within the physiotherapy profession. By including only physiotherapists, however, we excluded the perspectives of other important stakeholders, such as people with disabilities and patient advocacy groups. Exploring the perspectives of these groups is an important area for future research. Finally, we did not recruit participants from Canada's three territories (Nunavut, Yukon, and Northwest Territories), who may hold an important perspective to explore in future research.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of leading Canadian advocates within the physiotherapy profession regarding the attributes deemed necessary to excel in the advocate role. This is the first study to describe attributes necessary for success in the advocate role in the profession of physiotherapy specifically. Eight key attributes were identified as necessary for success in the role of advocate: collaboration, communication, scholarly practice, management, professionalism, passion, perseverance, and humility. Five of these attributes reflect current roles defined in the ECP. It was found that successfully demonstrating the advocate role requires the ability to integrate these attributes and adapt them depending on the advocacy situation. Also, while participants identified collaboration, communication, and scholarly practice as the most important attributes required for success in advocacy, it was noted that different situations may require drawing more heavily on different advocacy attributes.

These findings have several implications for practice and education. Curricula could approach the development of the advocate role in students by developing the other ECP roles and the additional attributes of passion, perseverance, and humility. Evaluation of competence in the advocate role should measure performance in the eight attributes identified, as well as the ability to integrate these attributes in a context-appropriate manner. Exploring the perspectives of patient advocacy groups and other health care professionals may provide a more comprehensive view on how physiotherapists may be able to excel in the advocate role. These efforts may help physiotherapists become more successful advocates for their clients and the profession and, furthermore, increase their profile among health care professionals as effective advocates in Canada's changing health care landscape.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

It is important for physiotherapists to advocate for the needs of their individual patients, communities, populations, and the profession. The significance of advocacy is highlighted by the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada (ECP), released in October 2009, which describes the advocate role as an essential competency for physiotherapists. However, we know little about the attributes required for success in the advocate role.

What this study adds

This study identifies eight attributes viewed as important for excelling in the advocate role. Five of the eight attributes are also part of the ECP: collaboration, communication, scholarly practice, management, and professionalism; the three additional attributes are passion, perseverance, and humility. Identifying these attributes is an important first step in understanding how competence in the advocate role can be developed among physiotherapy students and practitioners and, most importantly, how physiotherapists can excel in advocating for their clients, communities, populations, and the profession.

Physiotherapy Canada 2014; 66(1);74–80; doi:10.3138/ptc.2013-05

References

- 1.National Physiotherapy Advisory Group. Essential competency profile for physiotherapists in Canada [Internet] Toronto: National Physiotherapy Advisory Group; 2009. [cited 2012 Jul 16]. [updated 2009 Oct]. Available from: http://www.physiotherapy.ca/getmedia/fe802921-67a2-4e25-a135-158d2a9c0014/Essential-Competency-Profile-2009_EN.pdf.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank JR, Danoff D. The CanMEDS initiative: implementing an outcomes-based framework of physician competencies. Med Teach. 2007;29(7):642–7. doi: 10.1080/01421590701746983. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590701746983. Medline:18236250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.College of Physiotherapists of Ontario. Ensuring quality care in practice settings [Internet] Toronto: The College; 2012. [cited 2012 Jul 16]. [updated 2012]. Available from: http://www.collegept.org/(S(tqhgjx55tdokmbmosjdg4q45))/Resources/PracticeScenarios/AdvocacyforQualityPracticeSettings. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nova Scotia College of Physiotherapists. Professional practice standards for physiotherapists [Internet] Dartmouth: The College; 2008. [cited 2012 Nov 26]. [updated 2008 Feb 28]. Available from: http://nsphysio.com/resources/Practice+Standards+for+Physiotherapists+2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Nursing Association. Canadian registered nurse examination competencies June 2010–May 2015 [Internet] Ottawa: The Association; 2011. [cited 2012 Jul 16]. [updated 2011]. Available from: http://www2.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/nursing/rnexam/competencies/default_e.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Profile of practice of occupational therapists in Canada [Internet] Ottawa: The Association; 2012. [cited 2013 Jan 6]. [updated 2012 Oct]. Available from: http://www.caot.ca/pdfs/2012otprofile.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mu L, Shroff F, Dharamsi S. Inspiring health advocacy in family medicine: a qualitative study. [cited 2012 Jul 16];Educ Health [Internet] 2011 Apr;24(1):1–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21710421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dharamsi S, Richards M, Louie D, et al. Enhancing medical students' conceptions of the CanMEDS Health Advocate Role through international service-learning and critical reflection: a phenomenological study. Med Teach. 2010;32(12):977–82. doi: 10.3109/01421590903394579. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01421590903394579. Medline:21090951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hufford L, West DC, Paterniti DA, et al. Community-based advocacy training: applying asset-based community development in resident education. Acad Med. 2009;84(6):765–70. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a426c8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a426c8. Medline:19474556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallik M. Advocacy in nursing--perceptions of practising nurses. J Clin Nurs. 1997;6(4):303–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.1997.tb00319.x. Medline:9274232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foley BJ, Minick MP, Kee CC. How nurses learn advocacy. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(2):181–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00181.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00181.x. Medline:12078544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhillon SK, Wilkins S, Law MC, et al. Advocacy in occupational therapy: exploring clinicians' reasons and experiences of advocacy. Can J Occup Ther. 2010;77(4):241–8. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2010.77.4.6. http://dx.doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2010.77.4.6. Medline:21090065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flynn L, Verma S. Fundamental components of a curriculum for residents in health advocacy. Med Teach. 2008;30(7):e178–83. doi: 10.1080/01421590802139757. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590802139757. Medline:18777416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–40. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G. Medline:10940958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welsh E. Dealing with data: using NVIVO in the qualitative data analysis process. [cited 2012 Jul 16];Forum Qual Soc Res [Internet] 2002 3(2) Art 26. Available from: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/865/1881. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanks RG. The medical-surgical nurse perspective of advocate role. Nurs Forum. 2010;45(2):97–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00170.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00170.x. Medline:20536758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaartio H, Leino-Kilpi H, Salanterä S, et al. Nursing advocacy: how is it defined by patients and nurses, what does it involve and how is it experienced? Scand J Caring Sci. 2006;20(3):282–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00406.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00406.x. Medline:16922982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]