ABSTRACT

Purpose: To investigate the use of constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) in Canadian neurological occupational and physical therapy. Method: An online survey was completed by occupational and physical therapists practising in Canadian adult neurological rehabilitation. We measured participants' practices, perceptions, and opinions in relation to their use of CIMT in clinical practice. Results: A total of 338 surveys were returned for a 13% response rate; 92% of respondents knew of CIMT, and 43% reported using it. The majority (88%) of respondents using CIMT employed a non-traditional protocol. Self-rating of level of CIMT knowledge was found to be a significant predictor of CIMT use (p≤0.001). Commonly identified barriers to use included “patients having cognitive challenges that prohibit use of this treatment” and “lack of knowledge regarding treatment.” Conclusions: Although the majority of respondents knew about CIMT, less than half reported using it. Barriers to CIMT use include lack of knowledge about the treatment and institutional resources to support its use. Identifying and addressing barriers to CIMT use—for example, by using continuing professional education to remediate knowledge gaps or developing new protocols that require fewer institutional resources—can help improve the feasibility of CIMT, and thus promote its clinical application.

Key Words: constraint-induced movement therapy, rehabilitation, stroke, surveys, upper extremity

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Étudier l'utilisation de la thérapie par le mouvement par contrainte induite (TMCI) en ergothérapie et en physiothérapie neurologiques au Canada. Méthode : Des ergothérapeutes et des physiothérapeutes pratiquant dans le secteur de la réadaptation neurologique des adultes au Canada ont répondu à un questionnaire en ligne. Nous avons mesuré les pratiques des participants, leurs perceptions et leurs opinions au sujet de leur utilisation de la TMCI en pratique clinique. Résultats : Au total, 338 questionnaires ont été renvoyés, ce qui donne un taux de réponse de 13 %; 92 % des répondants connaissaient la TMCI et 43 % ont déclaré l'utiliser. Les répondants utilisant la TMCI suivaient en majorité (88 %) un protocole non traditionnel. On a constaté que l'autoévaluation du niveau de connaissance de la TMCI constituait un prédicteur important de l'utilisation de la thérapie (p≤0,001). Les obstacles à l'utilisation mentionnés couramment incluaient « le fait que des patients ont des problèmes de cognition qui empêchent d'utiliser le traitement » et « le manque de connaissance du traitement ». Conclusions : Même si la majorité des répondants connaissait la TMCI, moins de la moitié a déclaré l'utiliser. Les obstacles à l'utilisation de la TMCI comprennent le manque de connaissance du traitement et de ressources institutionnelles pour en appuyer l'utilisation. La détermination et l'élimination des obstacles à l'utilisation de la TMCI—par exemple, en recourant à l'enseignement supérieur professionnel continu pour corriger les lacunes des connaissances et en créant de nouveaux protocoles qui nécessitent moins de ressources institutionnelles—peuvent aider à améliorer la faisabilité de la TMCI et en promouvoir ainsi l'application clinique.

Mots clés : Thérapie par le mouvement par contrainte induite, réadaptation, accident vasculaire cérébral, sondage, membre supérieur

Stroke is the leading cause of neurology-related disability and death in North America, affecting approximately 50,000 Canadian and 795,000 American adults each year.1,2 Recovery of upper-extremity (UE) function is a major problem for survivors of stroke, only 5% of whom regain full function.3

Constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is one intervention that has been shown to facilitate UE functional recovery in a particular subset of patients after stroke. Derived from basic studies in animals, CIMT combines repetitive task practice (RTP) with shaping,4 during which participants engage in meaningful functional activities with measurable progressions for which they receive positive feedback as the activities become increasingly more difficult; behavioural re-training (e.g., behavioural contract, problem solving to address barriers to affected limb use); and restraint of the unaffected UE.4,5 Several CIMT protocols have been developed, including a “traditional” or massed practice approach, a “non-traditional” or distributed practice approach,4,6–9 and variations on these two approaches.10,11 Traditional CIMT involves six hours a day of RTP combined with restraint of the unaffected UE for 90% of waking hours over 10 consecutive weekdays (therapy sessions do not occur on weekends).4,6 Conversely, modified CIMT, a non-traditional protocol, takes place over a 10-week period, involving RTP for 30 minutes/day, 3×/week, combined with 5 hours/day of unaffected UE restraint.7,8 Regardless of the specific protocol used, the client is generally required to have a degree of movement in the affected UE that, at a minimum, includes 10° of active wrist extension with a 10° extension of the thumb and at least two fingers.6,7 The need for this level of function and the corresponding capacity for active engagement with the treatment limits the number of people for whom CIMT is an appropriate intervention.12

Despite evidence of CIMT's effectiveness in people who meet the criteria for treatment,6,7,13–15 questions abound regarding its clinical feasibility.16–18 Prior articles have highlighted the fact that, even though CIMT is recommended for treating UE hemiparesis in national stroke care guidelines,19 it is not being implemented as standard practice for stroke care.20,21 The authors identify several barriers to the implementation of CIMT, including resource intensity and therapist- or patient-related factors. In a study examining therapists' opinions of CIMT, Page and colleagues reported that 74% of occupational and physical therapist respondents (n=85) believed that their institutions lacked the resources necessary to provide traditional CIMT.16 Our research team's observations suggest that CIMT is not routinely used in clinical practice and that when it is used, not all CIMT components are implemented.

Given the lack of studies examining the use of CIMT, empirical knowledge is needed about clinicians' perceptions, actual application, and perceived barriers to implementation. This knowledge would inform research on the clinical feasibility of CIMT and educational initiatives to facilitate its translation into clinical practice. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to explore usage patterns of CIMT among occupational and physical therapists practising in adult neurological rehabilitation in terms of frequency of use, parameters of treatment, and barriers to use. We also examined respondent characteristics to identify factors related to CIMT use.

Methods

Our study employed a non-experimental, quantitative research design using an online survey (Opinio version 6.5.1, ObjectPlanet Inc., Oslo, Norway). The study received approval from the Capital District Health Authority Research Ethics Board.

Participants and survey distribution

A total of 588 occupational therapists and 1,968 physical therapists who are licensed to practise in Canada and who practise in adult neurological rehabilitation were invited to participate. Neurological practice was defined as engagement in treating people with stroke, traumatic or acquired brain injury, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, or dystonia. All participants were members of the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT) or the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA).

We recruited occupational therapists directly via email with a link to the online survey. A list of email addresses of occupational therapists who self-identified as being involved in neurological practice and who had agreed to be contacted for research was purchased from CAOT. Physical therapists were recruited through a national email newsletter distributed by CPA to all its members (approximately 10,600), which included a brief description of the study and a link to the online survey and invited physical therapists who self-identified as practising in neurological rehabilitation to participate. At the time of survey distribution, 1,968 CPA members were actively involved in this area of practice. Follow-up reminders were sent to both occupational and physical therapists at 2 and 3 weeks after the initial invitation in the manner outlined above, and participants had 3 months to complete the survey. Respondents provided informed consent by completing and returning the survey.

Survey development and composition

Survey questions related to two broad categories: (1) respondent profile and (2) CIMT usage pattern. Survey content complied with three criteria: (1) questions were relevant to the study's purpose; (2) the wording was not leading (i.e., it did not provide the “correct” response for subsequent questions); and (3) completion time was <15 minutes.

Five “content experts” (3 occupational and 2 physical therapists) involved in neurological rehabilitation services in Canada, including CIMT, independently assessed the content and face validity of the penultimate draft of the survey. Their feedback was used to refine the final survey items.

The final version of the survey contained 48 questions. The majority of these were “close-ended” with a list of response choices; seven included “other, please specify” as an option to allow for a written answer. Three questions relating to the respondents knowledge of CIMT, experience with CIMT, and perceived effectiveness of CIMT used a five-point Likert-type scale. For example, level of CIMT knowledge was coded as follows: 1=not very knowledgeable, 2=minimally knowledgeable, 3=moderately knowledgeable, 4=knowledgeable, and 5=very knowledgeable. Ten questions required a typed response (e.g., “Based on your knowledge of CIMT, please list what the key components of CIMT are:”). For analysis of this question in particular, two researchers independently reviewed the responses and grouped them according to the themes that emerged (e.g., inclusion criteria, treatment duration and schedule, type of treatment). A third researcher resolved any discrepancies. The frequencies of responses per theme were tallied. Three categories described the components of CIMT: (1) restraint, (2) RTP, and (3) behaviour/shaping; a fourth category, “identified no components,” was used for blank responses and those that did not meet criteria for the three key component categories. Respondents also identified their practice location as “rural” or “urban,” and population size of practice location was determined from the first three digits of the postal code corresponding to the practice location. Finally, a free-response question at the end of the survey invited participants to comment on their clinical use of CIMT.

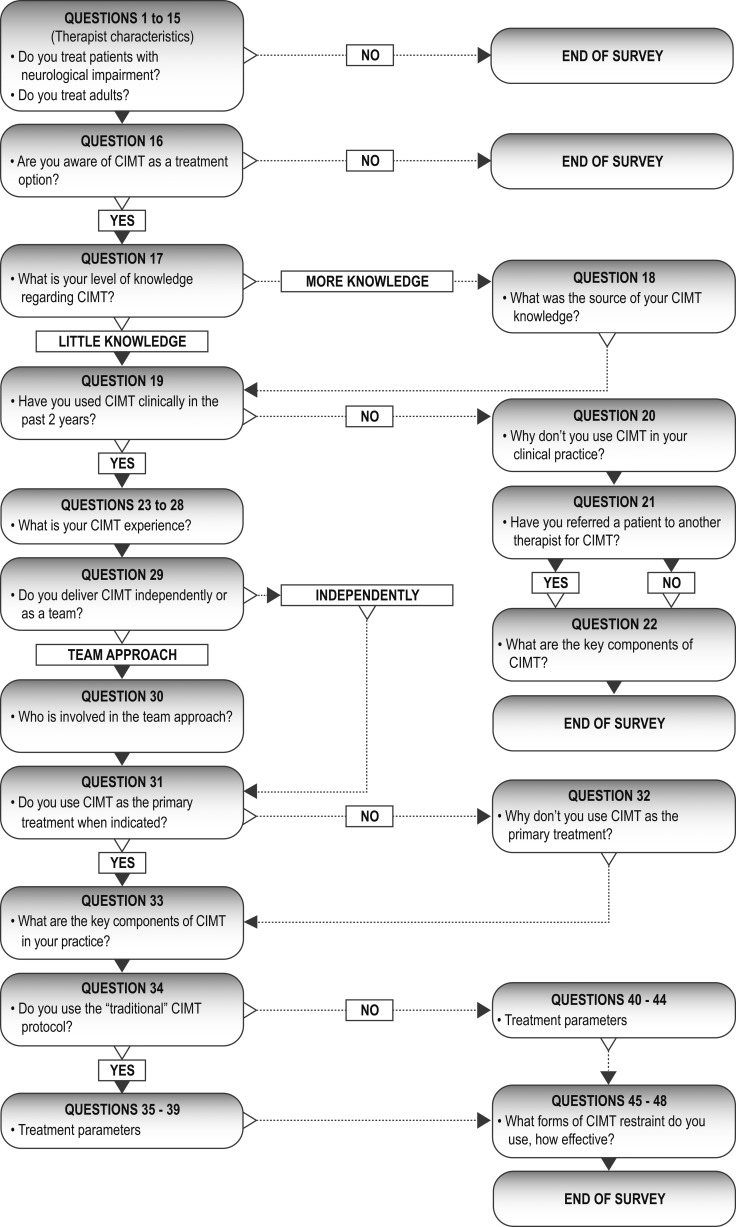

Depending on the responses to questions about CIMT usage patterns (e.g., “Are you aware of CIMT as a treatment option for upper limb hemiparesis?”), participants branched into different arms of the survey (see Figure 1). This funnelling pattern screened participants so that responses to certain survey questions came from only those who practiced in neurological rehabilitation and who had used CIMT clinically in the past two years. Participants who used CIMT were asked for characteristics of the protocol they employ. Responses from those participants who reported not using CIMT were also collected to identify barriers to CIMT use in this group. The survey was structured in such a way that participants responded to a maximum of 37 questions each. For further description of the survey, see Appendix 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of survey framework designed to identify participants who met the inclusion criteria and had used CIMT clinically in the past two years and to further classify respondents according to their use of CIMT.

Data analysis

Responses were treated as categorical variables. Because of the funnelling nature of the survey, the number of respondents was different for each question; we therefore report adjusted relative frequencies (%) and number of respondents who answered the question (n) throughout. For some questions, the adjusted relative frequencies do not sum to 100% because respondents could choose multiple responses. Throughout, we have grouped occupational and physical therapist responses for analysis. The rationale underlying this grouped approach is that, first, essential competencies for both professions include an expectation that therapists practice in an evidence-informed manner, including incorporating relevant and current knowledge into their practice22,23; and, second, although differences exist between professions related to specific areas of practice, the assessment and treatment of UE dysfunction post-stroke is a shared area of practice.24–26 The grouped approach is appropriate because it is reasonable to think that both occupational and physical therapist respondents have the potential to know about CIMT and the ability to use it in their practice.

To investigate practice setting size and CIMT use, we matched postal code data to the corresponding geographic region using householder counts and map information available from Canada Post (http://www.postescanada.ca/cpo/mc/business/tools/hcm/default.jsf?LOCALE=en); populations of these regions was then obtained from 2011 Statistics Canada data.27

To investigate therapist-related factors and CIMT use, we applied a binary logistic regression using a forward stepwise (Wald) model (SPSS version 19, IBM Canada Ltd., Markham, ON). The predictor variables chosen were number of years in practice, practice location, primary practice setting, and level of CIMT knowledge. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p<0.05. To examine variables that did not prove to be predictors of CIMT use through regression analysis, we cross-tabulated each variable against CIMT use. Using row percentages of the categories within each variable, we calculated the odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs28 of CIMT use between groups. For primary practice setting, we compared the odds of using CIMT for each setting category to the odds of using CIMT in an in-patient acute general setting. We defined the stages of stroke rehabilitation as follows: acute, 0–3 weeks; sub-acute, 3 weeks to 3 months; and chronic, >3 months post-stroke.

Results

Participants

Our total response rate was 13.2% (338 responses out of a possible 2,556). Of the 338 respondents, 39.9% (135/588, response rate of 23%) practised as occupational therapists and the remaining 60.1% (229/1,968, response rate of 10.3%) practised as physical therapists. The therapists were 89.5% (229) women and represented all provinces and territories except the Northwest Territories and Nunavut; the majority (51.9%) practised in Ontario. Respondent characteristics are described in Table 1. Nearly two-thirds (65.9%, 208) reported a bachelor's degree as their highest level of education. While respondents worked in both in- and outpatient settings, the greatest number (22.1%, 208) reported working primarily in general outpatient rehabilitation. Of all neurological diagnoses, stroke was the most commonly treated (88.6%, 236). Most respondents (75%, 136) practised in areas with a population greater than 55,000 people.

Table 1.

Distribution of Respondent Characteristics Relating to Therapist- and Therapy-Specific Factors

| Characteristics | Absolute frequency, no. | Adjusted relative frequency, % |

|---|---|---|

| Years practising (n=225) | ||

| 0–5 | 25 | 11.1 |

| 6–10 | 31 | 13.8 |

| 11–15 | 27 | 12.0 |

| 16–20 | 45 | 20.0 |

| 21–25+ | 97 | 43.1 |

| Practice location (n=213) | ||

| Urban | 170 | 79.8 |

| Rural | 43 | 20.2 |

| Primary practice setting (n=208) | ||

| In-patient acute general | 23 | 11.1 |

| In-patient rehabilitation general | 30 | 14.4 |

| Outpatient rehabilitation general | 46 | 22.1 |

| Private practice | 29 | 13.9 |

| In-patient stroke unit (acute/rehabilitation) | 30 | 14.4 |

| Other* | 50 | 24.0 |

| Treatment approach/intervention for upper limb hemiparesis (n=204) | ||

| Stretching | 181 | 88.7 |

| Strengthening | 175 | 85.8 |

| Motor learning/repetitive task practice | 166 | 81.4 |

| Modalities† | 158 | 77.5 |

| Imagery/mirror therapy | 150 | 73.5 |

| NDT/Bobath | 141 | 69.1 |

| Sensory re-training | 82 | 40.2 |

| CIMT | 78 | 38.2 |

| Bilateral movement therapy | 65 | 31.9 |

| PNF† | 61 | 29.9 |

| Other | 15 | 7.4 |

| Level of CIMT knowledge (n=185) | ||

| 1 – Not knowledgeable | 10 | 5.4 |

| 2 – Minimally knowledgeable | 38 | 20.5 |

| 3 – Moderately knowledgeable | 72 | 38.9 |

| 4 – Knowledgeable | 48 | 25.9 |

| 5 – Very knowledgeable | 17 | 9.2 |

| Level of CIMT experience (n=78) | ||

| 1 – Little experience | 9 | 11.5 |

| 2 – Minimally experienced | 22 | 28.2 |

| 3 – Moderately experienced | 28 | 35.9 |

| 4 – Experienced | 13 | 16.7 |

| 5 – Very experienced | 6 | 7.7 |

Includes skilled nursing/restorative care facility, community setting, home care and other.

Includes biofeedback, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, virtual reality, robotics, and serial casting.

NDT=neurodevelopmental treatment; CIMT=constraint-induced movement therapy; PNF=proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation.

CIMT usage

Some 92% of respondents (202) were aware of CIMT as a treatment option for UE hemiparesis; however, only 42.9% (182) said they had used CIMT in the last two years, and only 19.4% (72) used CIMT as a primary treatment (when indicated) for UE hemiparesis. CIMT was most commonly used in the chronic (74.0%, 77) and sub-acute (59.7%) stages of rehabilitation (vs. 7.8% in the acute stage) and was most often used for people with stroke (89.7%, 78). When asked to rate their level of experience with CIMT on a 5-point scale (1=little experience, 5=very experienced), most therapists (35.9%, 78) chose 3 (see Table 1).

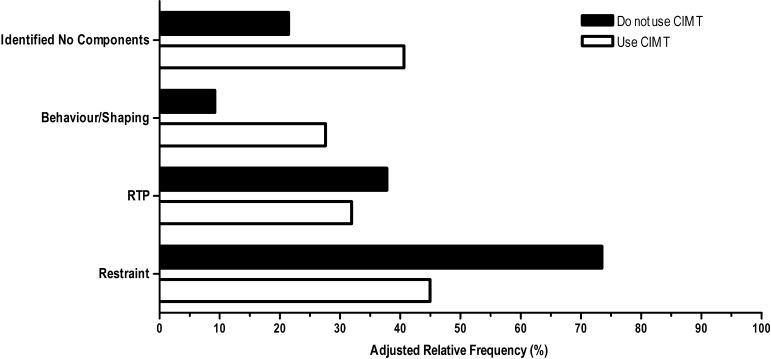

When asked to name the key components of CIMT, the majority of therapists using CIMT (88.4%, 69) did not name all three components (see Figure 2). Overall, however, this group did identify all three components more frequently than those who reported not using CIMT (11.6% of users vs. 9.2% of non-users). Surprisingly, 40.6% of CIMT users (vs. 21.4% of non-users) were unable to identify any of the key components. Common responses for CIMT components that were not categorized as behaviour/shaping, RTP, or restraint included treatment duration and schedule (12 users, 27 non-users), inclusion criteria (5 users, 24 non-users), and type of treatment (7 users, 14 non-users). A complete list of responses is available in Appendix 2.

Figure 2.

Frequency of respondents identifying key components of CIMT who do (n=69) and do not (n=98) use CIMT. “Identified no components” refers to respondents who did not identify any of the key components of CIMT. RTP=Repetitive Task Practice.

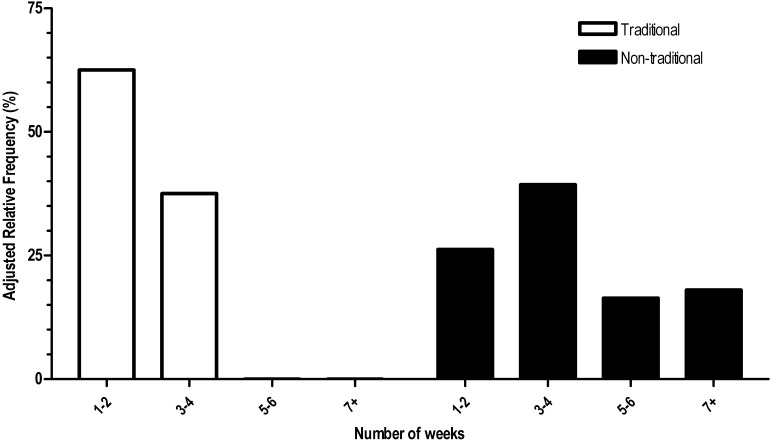

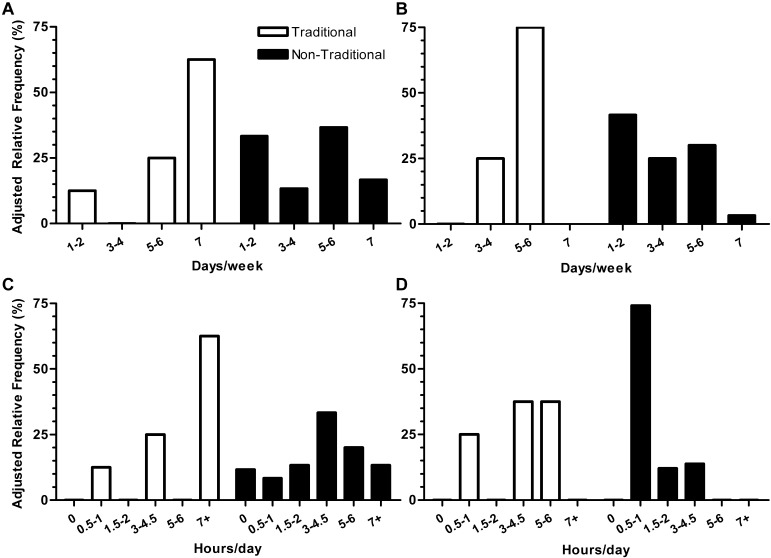

The majority of CIMT users reported using a non-traditional approach (88.4%, 69) rather than a traditional approach (11.6%, 69) (see Figures 3 and 4). The most commonly reported approach involved using CIMT for fewer hours per day over a longer duration than the traditional approach (see Figures 3 and 4B). There was considerable variability in the parameters reported for the delivery of non-traditional CIMT; for instance, hours of restraint per day varied from 0 to >7 (see Figure 3C), while days of RTP/shaping per week ranged from 1 to 7 (see Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

Total duration (weeks) of traditional (n=8) vs. non-traditional (n=61) use of CIMT.

Figure 4.

Parameters for use of traditional vs. non-traditional CIMT respectively, including: (A) days/week of restraint (n=8, n=60); (B) days/week of RTP/shaping (n=8, n=60); (C) hours/day of restraint (n=8, n=60); (D) hours/day of RTP/shaping (n=8, n=58). RTP=Repetitive Task Practice.

When asked about their level of knowledge related to CIMT, 38.9% of respondents (185) said they were moderately knowledgeable (rating of 3 on a 5-point Likert-type scale). More than half (60.7%, 173) reported obtaining their knowledge from research publications; other sources of knowledge are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Source of Knowledge Compared across Respondents' Reported Levels of CIMT Knowledge

| Level of knowledge; no. (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of knowledge | 2 (n=36) | 3 (n=70) | 4 (n=48) | 5 (n=17) | Total no. of responses |

| University education | 10 (27.8) | 26 (37.1) | 9 (18.8) | 5 (29.4) | 50 |

| Colleagues | 12 (33.3) | 36 (51.4) | 28 (58.3) | 10 (58.8) | 86 |

| Conferences | 7 (19.4) | 32 (45.7) | 28 (58.3) | 9 (52.9) | 76 |

| In-service | 12 (33.3) | 32 (45.7) | 26 (54.2) | 7 (41.2) | 77 |

| Courses/seminars | 12 (33.3) | 22 (31.4) | 24 (50) | 12 (70.6) | 70 |

| Workshops | 4 (11.1) | 13 (18.6) | 19 (39.6) | 8 (47.1) | 44 |

| Newspaper/news channel/magazines | 5 (13.9) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (4.2) | 1 (5.9) | 11 |

| Professional organization publication | 13 (36.1) | 29 (41.4) | 24 (50) | 7 (41.2) | 73 |

| Research publications | 12 (33.3) | 44 (62.9) | 34 (70.8) | 15 (88.2) | 105 |

| Best practice guidelines/evidence-based reviews | 6 (16.7) | 27 (38.6) | 28 (58.3) | 13 (76.5) | 74 |

| Stroke survivor/family member | 1 (2.8) | 6 (8.6) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (5.9) | 9 |

| Publicly accessible resources* | 4 (11.1) | 22 (31.4) | 14 (29.2) | 6 (35.3) | 46 |

Examples of publicly accessible resources include StrokeEngine (http://strokengine.ca/).

Note: Respondents with a knowledge level of 1 were not asked to complete this question.

Therapist-related factors and CIMT use

Self-reported level of CIMT knowledge predicted CIMT use (Wald=27.2, p≤0.001). A rating of 2 (minimally knowledgeable) or 3 (moderately knowledgeable) predicted less CIMT use (18.5, p≤0.001, and 7.9, p=0.005, respectively) relative to a rating of 5 (very knowledgeable). The odds of using CIMT were 31.3 (95% CI, 6.5–14.3) times as high for a very knowledgeable respondent compared to a minimally knowledgeable respondent, and 6.9 (95% CI, 1.8–26.3) times as high as for a respondent with moderate knowledge. CIMT use did not differ between respondents with knowledge self-ratings of 4 and 5, however. Respondents with very little knowledge of CIMT (rating of 1) were non-users of CIMT, as they did not report using it in the past 2 years.

We compared the odds of CIMT use within each non-significant variable from the regression analysis and found that primary practice setting influenced the odds of a therapist's use of CIMT. Compared to an in-patient acute general setting, the odds of using CIMT increased 4.9 (95% CI, 1.2–21.0) times for respondents working in in-patient general rehabilitation, 6.1 (95% CI, 1.5–25.9) times for those in a dedicated stroke unit (acute or rehabilitation), and 8.0 (95% CI, 2.0–31.4) times for those working in outpatient general rehabilitation; all increases are statistically significant (p<0.05). The odds of using CIMT were not significantly higher for those working in private practice.

CIMT effectiveness and barriers to use

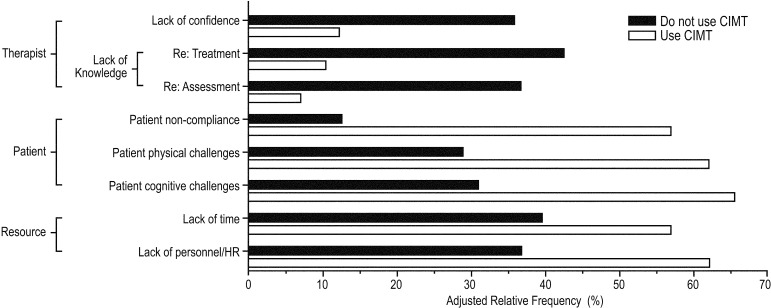

The majority of respondents (51.2%, 59) believed CIMT to be a moderately effective (3) or effective (4) UE therapy for people with stroke. Respondents identified various patient-, therapist-, and resource-related barriers to CIMT use (see Figure 5). Non-users of CIMT most commonly identified lack of knowledge as a barrier to use (42.3%, 104), while for CIMT users, the most commonly reported barrier (17.2%, 58) was a belief that their patients had cognitive challenges that might prohibit CIMT. Importantly, these data demonstrate differences in perceived barriers to use between those who use CIMT and those who do not; CIMT users primarily identified patient- or resource-related barriers, including lack of time, while non-users reported therapist-related factors, including lack of knowledge of and confidence related to CIMT treatment.

Figure 5.

Most selected barriers to CIMT use (users of CIMT, n=58; non-users of CIMT, n=104). HR=Human Resources.

Discussion

Although evidence shows CIMT to be an effective therapy for UE hemiparesis in patients who meet the criteria for treatment and although the majority of respondents know about CIMT, less than half reported using it. Based on our findings, discrepancies between awareness of CIMT and clinical use of this therapy suggest that both lack of knowledge and lack of resources are barriers to the implementation and use of CIMT in clinical practice.

CIMT use and parameters

Respondents most often reported using CIMT for fewer hours per day for a longer duration (i.e., using a non-traditional protocol), which suggests that more intense (i.e., traditional) protocols may be perceived as less clinically feasible. The treatment parameters reported by therapists who use non-traditional CIMT (see Figures 3 and 4) indicate variability in its delivery, which may reflect the integration of studies examining CIMT across the continuum from traditional to non-traditional protocols, resulting in limited consensus to the most effective and feasible protocol.13,14,29 While useful in determining overall effectiveness, this approach becomes problematic when therapists try to implement a specific CIMT protocol clinically. The variability we observed suggests that many therapists opt to develop their own method by integrating different evidence-based protocols. The discrepancy between CIMT treatment parameters reported in the research literature and those noted in our study suggests a problem in translating CIMT knowledge from research to clinical practice, although this conclusion should be considered in the context of the current sample. In light of these results, we must also consider the notion that CIMT protocols in their current form do not reflect the constraints of clinical practice and that these constraints should be taken into account as protocols are further studied and modified—that is, that clinical practice should drive research.

To assess respondents' knowledge about CIMT, we asked them to list its key components. Predictably, non-users of CIMT could not list all three components; more unexpectedly, however, the majority of CIMT users were also unable to identify all three components—for instance, less than 32% were able to identify the RTP and shaping/behavioural components of CIMT. Shaping in conjunction with RTP is considered one of the core components of treatment, and consequently, a critical part of any CIMT protocol.30,31 Thus, when CIMT is used clinically, therapists may not be implementing the treatment components that have been shown empirically to be effective including the use of shaping (e.g.,4–7). This inability to identify CIMT's fundamental components implies a lack of crucial knowledge of the therapy, at least among respondents to our current study. This finding reveals knowledge barriers not only among therapists who do not use CIMT but also among those who do. Continuing clinical education may be a means to target and reduce knowledge-related barriers for both users and non-users with the goal of delivering CIMT protocols in their evidence-based forms.

Therapist-related factors and CIMT use

Level of knowledge

Among respondents in our study, level of CIMT knowledge was a significant predictor of its use. Therapists who reported being very knowledgeable about CIMT had greater odds of using it in their clinical practice than those who reported minimal or moderate knowledge. The inability to distinguish CIMT use between very knowledgeable and knowledgeable therapists supports our conclusion that having only some knowledge of CIMT (i.e., minimal or moderate knowledge) is not sufficient to implement CIMT in clinical practice, at least within this sample of respondents. Notably, most respondents (59.4%, 130) reported having only some knowledge about CIMT, which may explain the discrepancy between the number of people who know about CIMT and the number who actually use it clinically. As highlighted below and in Figure 5, non-users of CIMT reported lack of knowledge as the primary barrier to CIMT use. Interestingly, while a similar number of respondents across all knowledge levels identified non-empirical sources of knowledge, a higher percentage of “very knowledgeable or knowledgeable” respondents than of those with minimal or moderate knowledge identified more research-based sources of knowledge (Table 2). The latter group tended to rely more on their entry-level education or on non-empirical sources of information. While these findings are specific to our small sample of therapists, they parallel prior observations on barriers to CIMT use and therapists' knowledge.20,21,32

Practice setting

Our findings show that therapists in our sample rarely use CIMT for their clients with acute stroke. Rather, they most often employ CIMT in in- and outpatient rehabilitation settings, likely because their clients in these settings are in the sub-acute to chronic stage of rehabilitation—the predominant patient groups in which CIMT's effectiveness has been examined in the literature.6,8,33 Moreover, there is a tendency for patients in the acute stage of recovery to be excluded from treatment because they do not meet the criteria for CIMT. Excluding these patients also helps to explain our findings: if fewer patients are eligible for treatment, therapists may be less likely to focus on CIMT, instead investing their time in interventions more appropriate to the acute stage of stroke recovery. While there is evidence that some forms of CIMT are effective in the acute phase, Brunner and colleagues suggest that CIMT not be used before 4 weeks post-stroke, since rapid improvement appears to occur during the first month of standard rehabilitation.12

Barriers to CIMT use

Therapists who use CIMT and those who do not reported different types of barriers to CIMT use: non-users more frequently identified therapist-related barriers (see Figure 5), while CIMT users more frequently identified barriers related to their patients (e.g., physical/cognitive challenges) and institutions (e.g., lack of resources). Given their lack of experience using CIMT, one might expect that non-users would be unaware of patient barriers and thus would not report them; the finding that non-users identified therapist-related factors as barriers to CIMT use supports the notion that increasing CIMT knowledge through training and education may increase clinical use of CIMT. Conversely, the fact that users of CIMT tended not to report barriers related to themselves (knowledge and confidence), and instead cited external barriers (related to their patients and institutional resources), suggests that in the absence of increased funding for in- and outpatient stroke rehabilitation, CIMT protocols may need further adaptation within the constraints of clinical practice.34 Specifically, researchers need to engage clinicians in conversations about evidence-based treatments to better align research with what is feasible in a clinical setting.

In regards to patient and institutional barriers, our findings indicate not only that a lack of resources can prevent CIMT use but also that patient non-compliance and physical and cognitive characteristics may be major barriers to implementing CIMT (see Figure 5, patient-related factors). Similarly, Page and colleagues have suggested that, when offered the traditional CIMT protocol, many patients with stroke do not participate, preferring a less intensive CIMT protocol.16 It is important to note that in identifying barriers to CIMT use, we did not distinguish between traditional and non-traditional protocols; our conclusions on the feasibility of traditional CIMT are drawn from the frequency with which therapists report using it relative to non-traditional CIMT. Therapists who report patient and institutional barriers to CIMT use may be doing so in the context of either a traditional or a non-traditional approach. Regardless of the protocol, the fact that CIMT users identified patient and institutional barriers suggests a need to further develop a CIMT protocol that is both effective and clinically feasible. It should also be noted that if therapists primarily treat people who do not meet the criteria for CIMT, they will not report using it, even though they may be knowledgeable and able to implement it.

Given regional differences in delivery of health care (e.g., publicly vs. privately funded services), barriers to CIMT use—specifically, patient and institutional barriers (e.g., patient populations and resources available to therapists)—may vary from those identified in our study. Irrespective of these differences, however, previous articles commenting on barriers to CIMT implementation in multiple countries17,20,21 have consistently identified therapist knowledge as a barrier to CIMT use. The results obtained from our sample of therapists reinforce prior observations that increasing therapists' knowledge of CIMT can contribute to more frequent use in clinical practice.

Our study has several limitations. First, the size of our sample resulted in low statistical power and potential for bias in the data. Although 338 therapists responded, not all completed every question. The low number of respondents was problematic for questions near the end of the survey (due in part to the funnelling nature of the survey) and those with multiple levels. Further, because we specifically targeted therapists practising in neurological rehabilitation, our sample may not be representative of the Canadian occupational therapy (OT)/physical therapy (PT) population as a whole. Our results and subsequent discussion should therefore be framed in the context of our sample. For instance, relatively wide CIs reflect the possible variability of the results, which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the applicability of the findings to the larger OT/PT population. Furthermore, the low response rate suggests a possible self-selection bias. Finally, because so few respondents (n=8) reported using traditional CIMT, we were unable to investigate whether certain factors could predict the type of CIMT protocol used.

Conclusion

Although research has shown CIMT to be an effective therapy for UE hemiparesis in post-stroke patients who meet the criteria for treatment, a discrepancy exists between the high level of awareness of CIMT and its low clinical use in our sample of occupational and physical therapists. Our findings regarding lack of knowledge about CIMT among practising therapists in our sample underscore the need for continuing education. Of equal importance, the number of therapists reporting patient and institutional barriers suggests a need to further modify current CIMT protocols to ensure that they fit with clinical practice while remaining effective. Therapists' perceptions of CIMT can inform recommendations for educational initiatives and the development of clinical guidelines. Furthermore, these results can guide future research, which should focus on achieving a balance between the clinical feasibility of CIMT and its effectiveness. This objective may be accomplished by investigating treatment dosage to find a quantity that is clinically feasible while eliciting optimal rehabilitation outcomes.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

Many people experience UE impairment following a stroke, and few regain full function. There is evidence that CIMT is effective in improving UE function after stroke; however, it is not known whether or how CIMT is being implemented in stroke rehabilitation. Although a few studies subjectively report barriers to CIMT use,16,20,21 no empirical studies have examined CIMT use, specifically clinicians' perceptions, actual clinical use, and perceived barriers to implementation.

What this study adds

This study is the first to report data from practising therapists relating to their use and perception of CIMT in clinical practice. Although awareness of CIMT was high among the sample of therapists, many do not use it clinically. Lack of knowledge about CIMT was the most commonly reported barrier to its implementation among therapists who do not use CIMT. Institutional resources and patient barriers were frequently cited by all respondents but particularly by therapists who report using CIMT. These data underscore the need for (1) educational initiatives to improve knowledge related to CIMT and (2) increased consultation between researchers and clinicians to optimize CIMT protocols for clinical practice. Both of these initiatives have the potential to improve clinical use of CIMT.

Appendix 1

Survey content followed three criteria:

the questions were relevant to the study's purpose;

the wording would not be leading (i.e., provide the ‘correct’ response for subsequent questions); and

the time to complete the survey would be less than 15 minutes.

Questions related to two broad categories:

Profile of respondents: the following information was collected to fully describe the sample population and to explore relationships between therapist-related factors and use of CIMT.

gender

profession (OT/PT)

percentage of practice treating adult neurological patients

number of years as OT/PT

number of years practicing in neurological OT/PT

practice setting (in-patient acute, outpatient rehabilitation, etc.)

practice location (urban vs. rural+3 digits of postal code)

province/territory

hours/week working as an OT/PT

level of education

interventions used to treat UL hemiparesis

Patterns of CIMT use: the following information was collected to assess the utilization pattern of CIMT among therapists working in neurological rehabilitation and to elucidate: i) their understanding of the components of CIMT and ii) the manner in which CIMT is delivered clinically.

awareness of CIMT as a treatment

level of knowledge regarding CIMT

source of CIMT knowledge

use of CIMT in clinical practice

knowledge regarding the components of CIMT

indications for use of CIMT

neurological conditions for which respondent uses CIMT

individuals involved in treatment delivery

parameters used when delivering CIMT (frequency, time)

effectiveness of CIMT in clinical practice

barriers to CIMT use

Appendix 2

List of responses (by theme) provided by CIMT users and non-users when asked to identify the key components of CIMT (see methods and results for details):

| Theme | Frequency (CIMT users) |

Frequency (non CIMT users) |

|---|---|---|

| Restraint | 31 | 72 |

| RTP | 22 | 37 |

| Shaping/behaviour | 19 | 9 |

| Use affected limb | 22 | 57 |

| Motivation | 13 | 0 |

| Treatment duration & schedule | 12 | 27 |

| Repetition | 11 | 10 |

| Type of restraint | 9 | 13 |

| Safety | 9 | 3 |

| Type of treatment | 7 | 14 |

| Commitment | 7 | 3 |

| Family support | 7 | 1 |

| Education | 6 | 0 |

| Inclusion criteria | 5 | 24 |

| Neuroplasticity | 5 | 8 |

| No knowledge | 4 | 10 |

| UL (upper limb) | 4 | 4 |

| Patient population | 4 | 3 |

| Team approach | 4 | 0 |

| Bimanual movements | 3 | 0 |

| Forced use | 2 | 6 |

| Learned disuse | 2 | 3 |

| Sensory/cognition | 2 | 1 |

| Testing | 2 | 0 |

| FITT | 1 | 0 |

| Consistency | 1 | 0 |

| Team knowledge | 0 | 2 |

| CVA | 0 | 1 |

| Specific training | 0 | 1 |

| Hand dominance | 0 | 1 |

| Motor tasks | 0 | 1 |

Physiotherapy Canada 2014; 66(1);60–71; doi:10.3138/ptc.2012-61

References

- 1.Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Statistics [homepage on the Internet] Ottawa: The Foundation; c2012. [cited 2012 Aug 1]. Available from: http://www.heartandstroke.com/site/c.ikIQLcMWJtE/b.3483991/k.34A8/Statistics.htm#stroke. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2-220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. Medline:22179539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barreca S. Management of the post stroke arm and hand: Treatment recommendations of the 2001 consensus panel. Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario; 2001. p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taub E, Crago JE, Burgio LD, et al. An operant approach to rehabilitation medicine: overcoming learned nonuse by shaping. J Exp Anal Behav. 1994;61(2):281–93. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1994.61-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1994.61-281. Medline:8169577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taub E, Uswatte G, Elbert T. New treatments in neurorehabilitation founded on basic research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(3):228–36. doi: 10.1038/nrn754. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrn754. Medline:11994754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf SL, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, et al. EXCITE Investigators. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006;296(17):2095–104. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2095. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.17.2095. Medline:17077374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page SJ, Levine P, Leonard A, et al. Modified constraint-induced therapy in chronic stroke: results of a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2008;88(3):333–40. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060029. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20060029. Medline:18174447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page SJ, Sisto S, Johnston MV, et al. Modified constraint-induced therapy after subacute stroke: a preliminary study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2002;16(3):290–5. doi: 10.1177/154596830201600307. Medline:12234091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page SJ, Boe S, Levine P. What are the “ingredients” of modified constraint-induced therapy? An evidence-based review, recipe, and recommendations. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2013;31(3):299–309. doi: 10.3233/RNN-120264. Medline:23396369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dromerick AW, Lang CE, Birkenmeier RL, et al. Very Early Constraint-Induced Movement during Stroke Rehabilitation (VECTORS): a single-center RCT. Neurology. 2009;73(3):195–201. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b27. Medline:19458319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin KC, Wu CY, Wei TH, et al. Effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy on reach-to-grasp movements and functional performance after chronic stroke: a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(12):1075–86. doi: 10.1177/0269215507079843. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269215507079843. Medline:18042603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunner IC, Skouen JS, Strand LI. Recovery of upper extremity motor function post stroke with regard to eligibility for constraint-induced movement therapy. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(3):248–57. doi: 10.1310/tsr1803-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1310/tsr1803-248. Medline:21642062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peurala SH, Kantanen MP, Sjögren T, et al. Effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy on activity and participation after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(3):209–23. doi: 10.1177/0269215511420306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269215511420306. Medline:22070990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi YX, Tian JH, Yang KH, et al. Modified constraint-induced movement therapy versus traditional rehabilitation in patients with upper-extremity dysfunction after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(6):972–82. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.036. Medline:21621674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson T, Thalman L, Christie H, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy compared to dose-matched interventions for upper-limb dysfunction in adult survivors of stroke: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Physiother Can. 2012;64(4):397–413. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2011-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2011-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page SJ, Levine P, Sisto S, et al. Stroke patients' and therapists' opinions of constraint-induced movement therapy. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16(1):55–60. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr473oa. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0269215502cr473oa. Medline:11837526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterr A, Szameitat A, Shen S, et al. Application of the CIT concept in the clinical environment: hurdles, practicalities, and clinical benefits. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2006;19(1):48–54. doi: 10.1097/00146965-200603000-00006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00146965-200603000-00006. Medline:16633019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevenson T, Thalman L. A modified constraint-induced movement therapy regimen for individuals with upper extremity hemiplegia. Can J Occup Ther. 2007;74(2):115–24. doi: 10.1177/000841740707400204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000841740707400204. Medline:17458370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, Bayley M, et al. Canadian best practice recommendations for stroke care (Updated 2010) Ottawa: Canadian Stroke Network, Group CSSBPaSW; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker J, Pink MJ. Occupational therapists and the use of constraint-induced movement therapy in neurological practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2009;56(6):436–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00825.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00825.x. Medline:20854555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viana R, Teasell R. Barriers to the implementation of constraint-induced movement therapy into practice. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2012;19(2):104–14. doi: 10.1310/tsr1902-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1310/tsr1902-104. Medline:22436358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.COTO. Essential competencies of practice for occupational therapists in Canada. College of Occupational Therapists of Ontario; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.CPA. Essential competency profile for physiotherapists in Canada. Canadian Physiotherapy Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shearer B, Burnham J, Wall JC, et al. Physical and occupational therapy: what's common and what's not? Int J Rehabil Res. 1995;18(2):168–74. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199506000-00011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004356-199506000-00011. Medline:7665263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Booth J, Hewison A. Role overlap between occupational therapy and physiotherapy during in-patient stroke rehabilitation: an exploratory study. J Interprof Care. 2002;16(1):31–40. doi: 10.1080/13561820220104140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13561820220104140. Medline:11915714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith S, Roberts P, Balmer S. Role overlap and professional boundaries: future implications for physiotherapy and occupational therapy in the NHS: forum. Physiotherapy. 2000;86(8):397–400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9406(05)60828-0. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Statistics Canada. Census profile [homepage on the Internet] Ottawa: Statistics Canada; c2012. [cited 2012 Jul 25]. [updated 2013 May 07]. Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E. [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Sullivan LM, Beiser AS. Introductory applied biostatistics. Toronto: Thomson Brooks/Cole; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corbetta D, Sirtori V, Moja L, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46(4):537–44. Medline:21224785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gauthier LV, Taub E, Perkins C, et al. Remodeling the brain: plastic structural brain changes produced by different motor therapies after stroke. Stroke. 2008;39(5):1520–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.502229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.502229. Medline:18323492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uswatte G, Taub E, Morris D, et al. Contribution of the shaping and restraint components of Constraint-Induced Movement therapy to treatment outcome. NeuroRehabilitation. 2006;21(2):147–56. Medline:16917161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salbach NM, Jaglal SB, Korner-Bitensky N, et al. Practitioner and organizational barriers to evidence-based practice of physical therapists for people with stroke. Phys Ther. 2007;87(10):1284–303. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070040. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20070040. Medline:17684088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page SJ, Sisto SA, Levine P. Modified constraint-induced therapy in chronic stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81(11):870–5. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200211000-00013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002060-200211000-00013. Medline:12394999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medical Advisory Secretariat HQO; Services OHQ, editor. Constraint-induced movement therapy for rehabilitation of arm dysfunction after stroke in adults: an evidence-based analysis. Toronto: Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series; 2011. pp. 1–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]