ABSTRACT

Purpose: To explore the perspectives of Canadian physiotherapists with global health experience on the ideal competencies for Canadian physiotherapists working in resource-poor countries. Method: A qualitative interpretive methodology was used, and the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada, 2009 (ECP), was employed as a starting point for investigation and analysis. Semi-structured one-on-one interviews (60–90 minutes) were conducted with 17 Canadian physiotherapists who have worked in resource-poor countries. Descriptive and thematic analyses were conducted collaboratively. Results: The seven ECP roles—Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Manager, Advocate, Scholarly Practitioner, and Professional—were all viewed as important for Canadian physiotherapists working in resource-poor countries. Two roles, Communicator and Manager, have additional competencies that participants felt were important. Three novel roles—Global Health Learner, Critical Thinker, and Respectful Guest—were created to describe other competencies related to global health deemed crucial by participants. Conclusions: This is the first study to examine competencies required by Canadian physiotherapists working in resource-poor countries. In addition to the ECP roles, supplementary competencies are recommended for engagement in resource-poor countries. These findings align with ideas in current global health and international development literature. Future research should examine the relevance of these findings to resource-poor settings within Canada.

Key Words: world health, developing countries, competency-based education, qualitative research

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Analyser ce que les physiothérapeutes du Canada qui ont de l'expérience en santé dans le monde pensent des compétences idéales des physiothérapeutes canadiens œuvrant dans des pays pauvres en ressources. Méthode : À partir d'une méthodologie d'interprétation qualitative et en nous fondant sur le Profil des compétences essentielles des physiothérapeutes au Canada, 2009 (CEP) comme point de départ de l'étude et de l'analyse, nous avons procédé à des entrevues personnelles et structurées (60 à 90 minutes) auprès de 17 physiothérapeutes du Canada qui ont travaillé dans des pays pauvres en ressources. Des analyses descriptives et thématiques ont été réalisées en collaboration. Résultats : Les sept rôles reliés aux CEP—expert, communicateur, collaborateur, gestionnaire, promoteur, érudit et professionnel—ont tous été considérés comme importants pour les physiothérapeutes canadiens qui travaillent dans des pays pauvres en ressources. Deux rôles, soit ceux de communicateur et de gestionnaire, comportent des compétences supplémentaires que les participants ont jugées importantes. Trois rôles nouveaux—apprenant en santé dans le monde, penseur critique et invité respectueux—ont été créés de façon à décrire d'autres compétences liées à la santé dans le monde jugées cruciales par les participants. Conclusions : Il s'agit de la première étude qui porte sur les compétences dont ont besoin les physiothérapeutes canadiens travaillant dans des pays pauvres en ressources. Outre les rôles reliés aux CEP, d'autres compétences sont recommandées pour travailler dans des pays pauvres en ressources. Ces constatations concordent avec les concepts que véhiculent des publications courantes sur la santé dans le monde et le développement international. Des recherches futures devraient porter sur la pertinence des constatations pour les contextes pauvres en ressources au Canada.

Mots clés : santé dans le monde, pays en développement, spécialité de la physiothérapie, formation basée sur les compétences, recherche qualitative

Physiotherapists from resource-rich countries are increasingly engaging in paid or volunteer work in resource-poor countries, consistent with a larger trend among health professionals toward involvement in global health work.1–4 Disability is widespread in resource-poor countries,5 and rehabilitation professionals, and specifically physiotherapists, have a unique and important role to play in global health by virtue of their expertise in maximizing function related to disability.1,5

The growing interest in global health work, however, has been paralleled by critical questioning of the effectiveness of current approaches, which has highlighted differences in the contexts, challenges, and shortcomings that may exist in global health efforts.6–8 Potential negative impacts include a lack of sustainability7 and the disruption of local cultures and systems.7,9 Differences in the contexts that arise in global health settings have also been highlighted, including the challenges of working with limited resources1,7,9 and communication barriers due to language differences.1,6

Given this increased attention to the complexities of global health work, several authors have suggested approaches to address these concerns. Suchdev and colleagues7 developed a framework of seven guiding principles for short-term medical trips: having a clearly defined mission, collaborating with local communities, educating relevant parties, committing to the interests of local communities, working effectively as a team, building capacity for sustainability, and periodically evaluating program outcomes. Pinto and Upshur6 have argued that the unique challenges of global health work require an understanding of four ethical principles—humility, introspection, solidarity, and social justice—that encompass concepts such as recognizing personal limitations, reflecting on one's motivations, and understanding how global health work differs from health work in one's home country.6 The WEIGHT Guidelines8 on best practices for global health training have also attracted attention for their comprehensive, if daunting, articulation of 33 areas to enhance global health engagement, including recommendations for multiple stakeholders such as the sending institutions, trainees, and sponsors. While these frameworks can provide a conceptual basis for promoting global health work, the development of competencies can help to facilitate translation of these ideas to practice.

Within health care, competency has been defined as the foundation of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that professionals carry with them throughout their careers and that have been created to better serve societal needs and promote effective practice.10–13 Global health competencies have been explored by authors from different fields within health care.14–16 In medicine, both Battat and colleagues14 and the Global Health Education Consortium15 have recently attempted to consolidate the literature on global health competencies for medical students. Both of their frameworks emphasize the importance of knowledge about global health issues (e.g., the social and economic determinants of health and health care in resource-poor settings) as well as behaviours and skills (e.g., cross-cultural communication skills and the ability to perform a physical examination without technological support).14,15 Cole and colleagues16 developed global health competencies for Canadian public health practitioners that include knowledge of politics, determinants of health, cultural differences, and ethical issues related to global health. These competencies also articulate the importance of skills and attitudes such as critical self-reflection and cross-cultural communication skills in global health work.

Global health competencies have not yet been established in physiotherapy. However, the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada, 200912 (ECP), was developed to guide physiotherapy practice within Canada. The ECP has defined seven roles for physiotherapists: Expert, Communicator, Collaborator, Manager, Advocate, Scholarly Practitioner, and Professional.12 Each role is described through key competencies.12 The ECP seeks to reflect “the diversity of physiotherapy practice and helps support evolution of the profession in relation to the changing nature of practice environments.”12(p.4) The global health setting may be considered one such “practice environment,” given Canadian physiotherapists' growing interest in resource-poor countries. However, the relevance of the seven ECP roles or other competencies for physiotherapists in global health has yet to be explored. The purpose of our study, therefore, was to explore the perspectives of Canadian physiotherapists with global health experience on the ideal competencies for Canadian physiotherapists working in resource-poor countries.

Methods

Our study used qualitative methods within an interpretivist, constructivist paradigm.17 The study received ethics approval from the University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

Participants

Participants were sought who (1) had worked in Canada as a physiotherapist for a minimum of 1 year; (2) had a minimum of 6 months' cumulative working experience (paid or unpaid) as a physiotherapist in one or more resource-poor countries over the course of one or multiple visits; and (3) spoke English. For the purposes of this study, we use the term resource-poor country to refer to countries classified as part of the low-income or lower-middle-income groups, based on the World Bank's calculation of 2010 per capita gross national income.18 Working experience as a physiotherapist was not limited to clinical practice but was open to various roles a physiotherapist might play, including educator, consultant, manager, or any combination of roles.

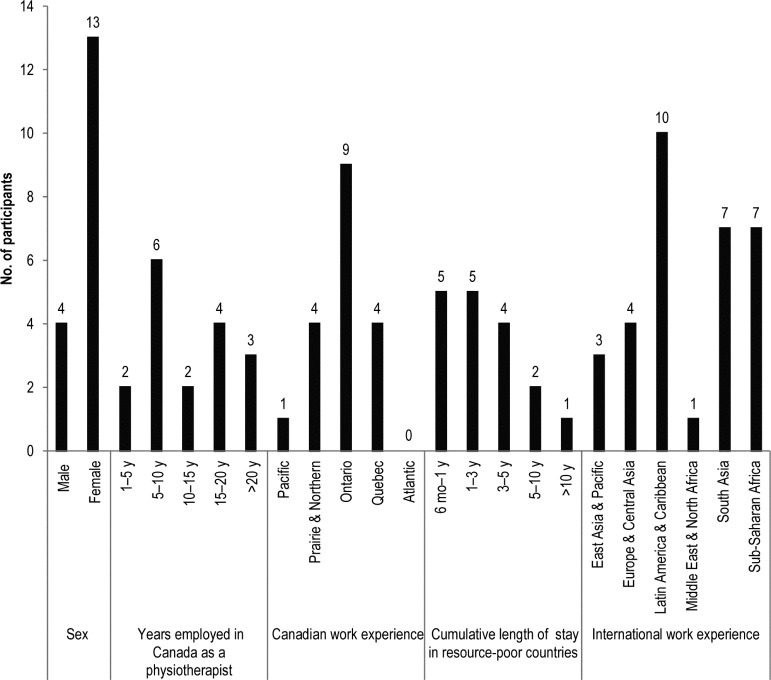

In addition to these criteria, we sought diversity across several areas deemed relevant to our inquiry: (1) sex (at least four male and four female participants); (2) international experience (the resource-poor countries where participants worked included at least three of the six following regions: Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, and South Asia);18 and (3) Canadian experience (the regions where participants worked as a physiotherapist included at least three of the following five regions in Canada: Pacific, Prairie and Northern, Ontario, Quebec, and Atlantic).19 All participants provided informed consent. Participant demographics are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant demographics.

Note: The number of participants in the Canadian Work Experience and International Work Experience categories is greater than 17 because some participants have experience in more than one region.

Recruitment

Our recruitment strategy had three phases. In Phase 1, we sent recruitment messages via the Canadian Physiotherapy Association's International Health Division (IHD) electronic newsletter and the University of Toronto's International Centre for Disability and Rehabilitation (ICDR) discussion list. Interested physiotherapists contacted the research team and were sent an information letter, consent form, and the Quick Reference ECP.20 Phase 2 was initiated after the first six participants were recruited; in this phase, we deliberately sought participants with characteristics not yet reflected in our sample by adding specific sampling criteria to the recruitment message and resending it through the IHD and ICDR mechanisms. In Phase 3, which was implemented after 12 participants had been recruited, the research team sent targeted recruitment messages via their professional networks to achieve the planned sample size and diversity.

The sample size was initially set at 12–15 participants, due to the study's time constraints, but was increased to 17 participants because our recruitment strategies worked well and we had identified emerging findings that would benefit from further exploration.

Data collection

Data was collected using semi-structured, one-on-one interviews lasting 60 to 90 minutes. Members of the research team conducted interviews by telephone, via Skype, or in person. The interview guide, which we developed collaboratively based on the ECP and global health literature, contained open-ended questions related to participants' experiences, the ideal competencies for working in resource-poor countries, the relevance of each of the ECP roles, and whether any of the ECP roles were not considered important. The interview guide was piloted with one physiotherapist and subsequently revised for enhanced clarity and flow. Each interview was audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and quality checked. To organize the data, we uploaded the transcripts to a qualitative software package, NVivo (QSR International [Americas] Inc., Burlington, MA).

Data analysis

Our approach to analysis drew on thematic content analysis17 and Jackson's collaborative approach21 to interpretation. Codes for the coding framework were first determined deductively, using the roles of the ECP;22 additional codes were derived inductively from key ideas that recurred in the transcripts.22 We established detailed descriptions of each code, piloted a draft coding framework on four transcripts, and modified the code definitions where necessary.17

Each transcript was coded separately by two investigators. Data assigned to each code were grouped together using NVivo, and a descriptive summary was created for each code to highlight the main ideas. All summary reports were discussed in collaborative analysis meetings, during which key ideas from the data were organized into themes. As part of this process, we compared the ECP roles with the findings in the data, as a result of which we expanded some pre-existing ECP competencies and created new roles. In addition, we generated schematic diagrams throughout the process to visually represent the results of the study until final results were achieved, which encouraged us to develop conceptual clarity and coherence with respect to the findings.23

Results

Participants identified 10 roles as important for Canadian physiotherapists working in resource-poor countries (see Figure 2), including all seven roles in the ECP. Five of these seven roles—Expert, Collaborator, Advocate, Scholarly Practitioner, and Professional—were described as having similar key competencies to those described in the ECP when applied to global health settings; additional key competencies were described for two of the ECP roles, Communicator and Manager. In addition to these roles, participants identified several other competencies they believed to be important that were not captured by the ECP roles. We therefore created three new roles: Respectful Guest, Global Health Learner, and Critical Thinker.

Figure 2.

Perspectives of Canadian physiotherapists regarding roles for working in resource-poor countries (developed based on the CanMEDS Diagram).13(p.2–3)

Dark petals=Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada, 2009 (ECP) role; light petals=new role; gradient petals=ECP role with additional competencies.

Perspectives on the ECP roles for working in resource-poor countries

Participants' perspectives on the ECP roles in global health settings largely confirmed the importance of the key competencies which describe these roles. Participants commented that the roles Communicator and Manager may need to be expanded to consider other circumstances that are different, or more emphasized, in resource-poor countries. Discussion points related to aspects of these roles that are most important to consider in resource-poor countries are summarized below.

Expert

Discussion of the Expert role related primarily to three topics. First, participants identified the importance of having clinical expertise; many recommended having several years of clinical experience before engaging in global health work. Because of the diverse contexts in which a physiotherapist might work, participants considered general physiotherapy knowledge to be more important than specialized knowledge. Second, participants identified the role of Expert in terms of being able to integrate the other ECP roles. Third, questions about the Expert role prompted several participants to challenge the assumption that one is an “expert” in global health settings. As one participant commented,

Going in thinking you are the expert, you are the saviour, you can make everything better in one week. It's very dangerous because then, coming in with that kind of attitude means that the community that you're going to has to rely on you. And that's very dangerous, because that doesn't match the sustainability issue.

(Participant 15)

Collaborator

Comments about the Collaborator role often overlapped with comments on the Communicator role, since participants viewed communication as a key strategy for facilitating collaboration. Participants emphasized the importance of competencies related to collaboration as they facilitate the building of important relationships with local individuals and communities.

Advocate

Most participants perceived competencies related to advocating on behalf of the profession and for individuals with disabilities as important in resource-poor countries, and emphasized teaching advocacy skills to local people and communities to encourage sustainability. Participants expressed a need to be flexible and advocate on behalf of the communities' interests rather than their own personal beliefs.

Scholarly Practitioner

Most participants agreed that engaging in reflective practice and lifelong learning, key tenets of the Scholarly Practitioner role, is essential for work in resource-poor countries. As one participant reflected, “We learn so much from our experience.… As much as we bring to the international population something positive, we also take something positive back home” (Participant 6). Some participants also commented on the concept of best practice, suggesting that understandings of best practice in Canada may not be relevant or appropriate in other settings and should be approached carefully.

Professional

Many participants noted the paucity of formal legal or ethical regulations guiding the physiotherapy profession in some resource-poor countries but emphasized that maintaining moral standards is fundamental to physiotherapy practice. Several participants stated that ethical practice should be intuitive for physiotherapists, believing it to be a basic tenet of being a health professional in any setting. Participants considered it important to “treat patients and counterparts there with exactly the same level of legal and ethical requirements that we would here” (Participant 16).

Communicator with additional key competency “communication skills for differences in language and culture”

All participants stressed the importance of competencies related to communication in their global health experiences. In addition to those competencies outlined in the Communicator role in the ECP, participants identified a need to manage the challenges associated with communication, including differences in language, through engaging translators, using non-verbal communication, or learning the local language. Participants also described the importance of understanding and adapting to the differences in cultural aspects of communication.

Manager with additional key competency “creativity and resourcefulness”

Most participants identified the importance of managing time, resources, individual practice, and support personnel. With respect to managing resources, participants emphasized the need to be creative and resourceful, a competency not currently described in the ECP, based on the lack of access to or difficulty in accessing human and physical resources. As one participant explained, “I did splinting using … cast material, a clothes hanger, guitar strings, and elastic that I got from the tailor down the road” (Participant 11).

Perspectives on new roles for working in resource-poor countries

In addition to the importance of the ECP roles, our participants identified several ideal competencies as essential for work in resource-poor countries that are not encompassed by these roles. Three new roles, Global Health Learner, Critical Thinker, and Respectful Guest, were created to comprise these competencies, as described below.

Global Health Learner

Every participant stressed the importance of having knowledge and continually learning about subjects relevant to global health. Participants perceived two key competencies required for this role: (1) knowledge about major concepts of global health and international development and (2) knowledge about the local setting. Awareness of major concepts such as sustainability, capacity building, the history of colonialism, and core concepts in postcolonial theory was deemed highly important by many participants. Often, participants emphasized the importance of sustainable development such as, for example, encouraging local involvement and ownership and decreasing reliance on foreign assistance.

Participants also stressed the importance of having knowledge about the local setting, including the area's culture, history, social norms, belief systems, health and educational systems, and safety concerns. They described the importance of understanding how local culture is shaped by the history of that community: “There are a few hundred years of history there … but it plays out on a daily basis” (Participant 10). Participants also identified that a lack of basic knowledge of the country's belief systems and health care systems compromises effective work.

Including these competencies within the new role of Global Health Learner, rather than under the role of Expert, serves to emphasize the heightened importance of these competencies within global health settings, as stressed by our participants.

Critical Thinker

Most participants identified the role of the Critical Thinker in two capacities: (1) engaging in critical reflection of a personal nature and (2) engaging in critical reflection on major global health and international development debates. In relation to personal critical reflection, participants spoke about being aware of one's positionality in the resource-poor country, referring to the inherent power differentials that exist based on the privilege that accompanies being from a resource-rich country. One participant, commenting on the extent of this power differential, emphasized the trust that the local community appeared to have for foreign health professionals: “People would give me scalpels if I said, ‘Listen, I think I'm going to do a heart transplant’” (Participant 13). Participants also identified a need to reflect on one's motivations for working in resource-poor countries; they saw interrogating one's assumptions about entering into this work as both crucial and potentially difficult to achieve.

In relation to debates in the field of global health and international development, participants described critical thinking as understanding the factors that influence sustainability; understanding the potential harms of foreign involvement; and questioning the goals, values, and roles of partners in the field. Many participants spoke about sustainability in terms of ensuring that the work being done can continue once foreign health professionals have returned to their home countries. They described how educating and training local people could result in more sustainable outcomes; however, they also commented that true sustainability is extremely challenging to achieve.

Respectful Guest

The Respectful Guest role involves being committed to the best interests of the host community through respect, open-mindedness, flexibility, and humility. Participants described the need to be open-minded to the country's culture and to understand “that their whole value system, their whole way of seeing the world can be different from what yours is” (Participant 11). Many participants emphasized humility, explaining that being humble and recognizing that one is not an expert in someone else's culture are essential attitudes when working in resource-poor countries. One participant offered this example of the importance of respecting local communities:

We didn't have Martians come in the 1930s telling us, “You should be doing this and you should be doing that to your [people with disabilities].” We were treating them with the means that we had at that time and with the values that we had at that time and so on. And we're coming in from our rich countries and sort of imposing a standard, a set of values … and we sort of take for granted that that's where people should be at.

(Participant 12)

Discussion

Physiotherapy beyond our borders

Our study is the first to investigate ideal competencies for physiotherapists from resource-rich countries working in resource-poor countries, as well as provide a uniquely Canadian standpoint through its engagement with the ECP. Overall, the experienced Canadian physiotherapists in our sample believed that the seven roles of the ECP have continued importance for work in resource-poor countries, which suggests that these roles may be fundamental to physiotherapy practice regardless of location. However, participants also identified important concepts that did not fit within this framework, which led us to create new competencies and roles. The need for additional competencies for global health work is consistent with other health fields,14,16,24 where supplementary global health competencies have also been identified. This insight points to the significance of key global health issues that may be salient regardless of profession.

Furthermore, the concepts related to critical thinking, self-reflection, and humility that emerged in this study may be equally relevant for settings within Canada. Understanding the history of colonialism in Canada is crucial for working with Canada's Aboriginal communities.25 Given Canada's cultural diversity, understanding, open-mindedness, and adaptability are imperative when dealing with any patient or community whose cultural orientations differ from one's own. Furthermore, there are many resource-poor settings in Canada that face similar challenges related to the social and economic determinants of health as the resource-poor countries described in this study.

Rethinking the essential roles for physiotherapists

This study highlights the importance of understanding cultural differences to improve communication and develop productive relationships when working in resource-poor countries. Cultural competency describes the ability to understand culture and behave in ways that allow an individual to respectfully interact within a culture.26,27 Cultural competency in global health is well described in various health fields.24,26 Lattanzi and Pechak27 identified the importance of cultural training for physiotherapy and occupational therapy students engaging in international internships, which was said to help students and faculty “recognize and negotiate through cultural misalignments in a successful manner.”27(p.107) Dupre and Goldgood26 have also argued that competence in cross-cultural communication can minimize communication problems. Despite the multicultural nature of Canada, the ECP does not specifically discuss competency related to culture.12 The ECP does describe related concepts, such as “sensitivity to the uniqueness of others”12(p.9) (Communicator) and respect for the individuality and autonomy of clients (Professional),12 but our participants emphasized the importance of understanding cultural differences to a much greater extent than is articulated in the ECP.

Beyond knowledge, toward reflexivity

Global health competencies for other professions, similarly, have also identified the importance of knowledge about major global health concepts.14–16 Knowledge about local settings, which our participants identified as important, has also been identified in medical global health competencies as the need to appreciate differences and contrasts in health systems, expectations, and settings.14 In addition, similar to our Global Health Learner role, Cole and colleagues16 identified a need to “educate oneself about global health issues on an ongoing basis,”16(p.396) emphasizing the need for continued learning about these topics. However, participants in our study were adamant that global health competencies extend beyond acquiring knowledge to critical thinking and engaging with key global health debates.

Critical thinking has previously been identified as important for global health work. Global health competencies for public health describe the need to “recognize the interaction between political and economic history, power, participation and engagement globally”16(p.396) and to show commitment to sustainable development.16 Similarly, Pinto and Upshur6 have emphasized the importance of understanding power relations and oppression created through history to more fully understand global health issues.

Critical reflection of a personal nature shares similarities to Pinto and Upshur's6 principle of introspection, which includes examining one's motivations for involvement, what one has to offer, and one's background and the related implications for power relations. Similarly, global health competencies for public health include the ability to “critically self-reflect upon one's own social location and appropriately respond to others in their diverse locations.”16(p.396) For physicians, Like and colleagues24 identified the importance of having an awareness of “how one's own cultural values, assumptions, and beliefs influence the provision of clinical care and are shaped by social relationships and the contexts in which we work and live.”24(p.291) These ideas reflect the concept of reflexivity, or being able to recognize what it is about each of us as individuals that has informed our thinking, values, and assumptions.28

Developing the capacity for reflexivity can enhance humility, respect, open-mindedness, and flexibility, which dovetails with the new role Respectful Guest. Pinto and Upshur6 previously identified the importance of humility for mitigating the adverse effects of power dynamics between resource-rich and resource-poor countries. They also addressed respect for local interests in terms of solidarity, or the importance of aligning the goals and values of students with those of the local community.6 Similarly, the need to “foster self-determination, empowerment and community participation in [global health] contexts”16(p.396) is a global health competency for public health practitioners that describes the need to work with and toward the goals of the local community.16 Competencies related to having a respectful mindset may address potential negative consequences of visiting health professionals imposing their personal or societal values on the host communities, helping to reduce interference with local communities' autonomy and perhaps also helping to “undermine neo-colonial trends that often permeate relationships between the North and South.”6(p.8)

Future directions for research

Future research should further explore the new proposed roles and competencies to develop greater conceptual depth around these ideas. Given the number of resource-poor settings in Canada,25,29 future research should also examine how the global health competencies proposed here may be relevant domestically as well as internationally. Finally, we note that global health competency frameworks have largely focused on the perspectives of individuals from resource-rich countries, with insufficient attention to individuals from resource-poor countries; future research should therefore adopt an approach that privileges the perspectives of health professionals and others within the resource-poor countries.

Future directions for policy and education

Our findings could be used as an early step toward developing a framework to guide physiotherapists from resource-rich countries working in resource-poor countries. Results may also inform Canadian physiotherapy curricula regarding training in global health for students interested in future practice or research related to global health, international clinical internships, or working in resource-poor environments in Canada. Finally, the findings of this study may also be pertinent to organizations involved in implementing global health work with regard to training and recruitment of physiotherapists for projects in resource-poor countries.

Limitations

Participants in this study played diverse roles when working in resource-poor countries, which may have produced differing perspectives on ideal competencies. A limitation of this study is that we did not purposively sample to include participants with a range of experiences across these roles, and therefore we cannot reflect on how types of international roles may have influenced participants' perspectives.

A further limitation is that participants were given information about the ECP before their interviews, which may have influenced their perceptions of the roles included in the ECP and, therefore, influenced the findings of the study.

Conclusion

The growing involvement of Canadian physiotherapists in resource-poor countries and the critical dialogues regarding global health work have made exploring ideal competencies for working in global health settings increasingly relevant. The results of our analysis suggest that in addition to the roles outlined in the ECP, there are other competencies that need to be considered for engagement in resource-poor countries. The new roles established in this study align with ideas in the literature on global health competencies and guiding principles, but are presented in a context that is applicable to Canadian physiotherapists. We hope this study will spark constructive dialogue on the promotion of health care work in resource-poor countries by Canadian physiotherapists.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

The Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada, 2009 (ECP), exists as a guiding framework for physiotherapists working in Canada. Existing studies have explored frameworks to guide engagement in global health settings for other health professions, but no study has investigated the ideal competencies for physiotherapists from resource-rich countries working in resource-poor countries.

What the present study adds

This is the first study to identify competencies recommended for Canadian physiotherapists working in resource-poor countries. These competencies are encompassed by 10 roles: the 7 ECP roles, with the addition of new competencies to the Communicator and Manager roles, and 3 new roles titled Global Health Learner, Critical Thinker, and Respectful Guest.

Physiotherapy Canada 2014; 66(1);15–23; doi:10.3138/ptc.2012-54

References

- 1.Alappat C, Siu G, Penfold A, et al. Role of Canadian physical therapists in global health initiatives: SWOT analysis. Physiother Can. 2007;59(4):272–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.59.4.272. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford E, Biggar JM, Leggett A, et al. Examining international clinical internships for Canadian physical therapy students from 1997 to 2007. Physiother Can. 2010;62(3):261–73. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.3.261. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/physio.62.3.261. Medline:21629605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron D. Working internationally. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2008;28(2):109–16. doi: 10.1080/01942630802031792. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01942630802031792. Medline:18846891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. 2000;32(8):566–72. Medline:11002868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization, the World Bank. World report on disability 2011 [Internet] Geneva: WHO Press; 2011. [cited 2012 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinto AD, Upshur RE. Global health ethics for students. Dev World Bioeth. 2009;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00209.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00209.x. Medline:19302567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suchdev P, Ahrens K, Click E, et al. A model for sustainable short-term international medical trips. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(4):317–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.04.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ambp.2007.04.003. Medline:17660105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crump JA, Sugarman J Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT) Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(6):1178–82. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527. http://dx.doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0527. Medline:21118918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jobe K. Disaster relief in post-earthquake Haiti: unintended consequences of humanitarian volunteerism. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2011;9(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.10.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.10.006. Medline:21130039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S, Paterson M, Medves J. Core competencies for health care professionals: what medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy share. J Allied Health. 2006;35(2):109–15. Medline:16848375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norman GR. Defining competence: a methodological review. In: Newfeld VR, Norman GR, editors. Assessing clinical competence. New York: Springer; 1985. pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Physiotherapy Advisory Group. Essential competency profile for physiotherapists in Canada, 2009 [Internet] National Physiotherapy Advisory Group; 2009. [cited 2012 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.alliancept.org/pdfs/alliance_resources_profile_2009_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank JR, editor. The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, et al. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-10-94. Medline:21176226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada's Resource Group, Global Health Education Consortium Committee. Global health essential core competencies [Internet] San Francisco: Global Health Education Consortium; 2010. [cited 2012 Jul 1]. Available from: http://globalhealtheducation.org/SitePages/Home.aspx/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cole DC, Davison C, Hanson L, et al. Being global in public health practice and research: complementary competencies are needed. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(5):394–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03404183. Medline:22032108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The World Bank. Data & statistics: country groups [Internet] Washington: The World Bank Group; 2011. [cited 2012 Jul 1]. Available from: http://go.worldbank.org/47F97HK2P0/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Government of Canada. Transport Canada: regions [Internet] Ottawa: Transport Canada; 2012. [cited 2012 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/regions.htm/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Physiotherapy Advisory Group. Quick reference: essential competency profile for physiotherapists in Canada, 2009 [Internet] National Physiotherapy Advisory Group; 2009. [cited 2012 Jul 1]. Available from: http://www.manitobaphysio.com/documents/ECQuickReferenceEnglish.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson SF. A participatory group process to analyze qualitative data. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(2):161–70. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/cpr.0.0010. Medline:20208250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott R, Fischer CT, Rennie DL. Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br J Clin Psychol. 1999;38(3):215–29. doi: 10.1348/014466599162782. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/014466599162782. Medline:10532145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Like RC, Steiner RP, Rubel AJ. STFM Core Curriculum Guidelines. Recommended core curriculum guidelines on culturally sensitive and competent health care. Fam Med. 1996;28(4):291–7. Medline:8728526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newbold KB. Problems in search of solutions: health and Canadian aboriginals. J Community Health. 1998;23(1):59–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1018774921637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1018774921637. Medline:9526726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dupre AM, Goodgold S. Development of physical therapy student cultural competency through international community service. J Cult Divers. 2007;14(3):126–34. Medline:18314814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lattanzi JB, Pechak C. A conceptual framework for international service-learning course planning: promoting a foundation for ethical practice in the physical therapy and occupational therapy professions. J Allied Health. 2011;40(2):103–9. Medline:21695371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phelan SK. Constructions of disability: a call for critical reflexivity in occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 2011;78(3):164–72. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2011.78.3.4. http://dx.doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2011.78.3.4. Medline:21699010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasylenki DA. Inner city health. CMAJ. 2001;164(2):214–5. Medline:11332318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]