Abstract

The Medical Home Clinic for Special Needs Children (MHCL) at Arkansas Children’s Hospital provides comprehensive care oversight for children with medical complexity (CMC). The objective of this study is to evaluate parent perceptions of health care delivery outcomes after 12 months of enrollment in the MHCL. This is a prospective cohort study of parents of MHCL patients, who completed surveys at initial and 12 months visits. Surveys assessed parent health, child health and function, family stress, and overall satisfaction, using previously validated measures and scales. Paired analyses examined differences in measures between baseline and 12 months. 120 of 174 eligible parents completed the follow-up survey at 12 months. Respondents were 63% white/Caucasian, 90% biological parent, and 48% with family income <$20K. From baseline to 12 months, a greater number of respondents reported having a care plan (53% vs 85%, p<.001); fewer respondents needed help with care coordination (78% vs 31%, p<.001). No changes were seen in reports of having emotional needs met. Parents reported a decline in the physical subscale of the SF-12 Health-Related Quality of Life measure (49.1 vs 46.4, p<.01), with those parents with ≥1 additional child with special needs reporting a marked decline (49.2 vs 42.5, p<.001). No other changes in family impact were found. We conclude that comprehensive care oversight may improve care coordination for parents of CMC, but no association with improved parent health was found. Future studies should identify the factors that influence parental burden and tailor clinical interventions to address such factors.

Keywords: Children with Special Health Care Needs, Children with Medical Complexity, Medically Complex Children, Chronic Disease Management, Family Impact

Introduction

Children with medical complexity (CMC) are an important subset of children with special health care needs (CSHCN), increasingly recognized for their substantial impact on the health care system (Cohen, Kuo, et al., 2011). As the highest resource utilizers of all children (Neff, Sharp, Muldoon, Graham, & Myers, 2004), CMC are clinically recognized by at least one chronic condition that results in high family-identified service need, medical equipment to address functional difficulties, multiple subspecialist involvement, and elevated health service use (Berry, Agrawal, et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2010; J. B. Gordon et al., 2007; Kelly, Golnik, & Cady, 2008; Tanios, Lyle, & Casey, 2009). Many CMC have neurodevelopmental delays, growth and nutritional/feeding problems, and technology dependence (Berry, Agrawal, et al., 2011). CMC account for increasing proportions of hospitalized children (Burns et al.; Simon et al.) and consume a disproportionate amount of health care resources compared to all children (Berry, Hall, et al., 2011; Neff et al., 2004).

The emotional, social, physical, and economic impact on families of CMC is substantial, due to the need for multiple subspecialty visits, medical equipment needs, and therapies to address neurodevelopmental concerns (Berry, Hall, et al., 2011; Srivastava, Stone, & Murphy, 2005). Families of CMC report high rates of employment loss, financial strain, and hours devoted to caregiving and care coordination (Kuo, Cohen, Agrawal, Berry, & Casey, 2011). Families report the medical care system is fragmented and difficult to navigate (Ghose, 2003; Ray, 2002). Primary care providers report difficulties in being able to provide needed services (Kuo, Robbins, Burns, & Casey, 2011). Comprehensive care models for CMC, frequently based in tertiary care centers, can provide multidisciplinary services, care coordination, and specific medical expertise for CMC (Berman et al., 2005; Berry, Agrawal, et al., 2011; J. B. Gordon et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2008; Klitzner, Rabbitt, & Chang, 2010). Although research is scant (Cohen, Jovcevska, Kuo, & Mahant, 2011), emerging evidence suggests substantial reductions in inpatient hospitalization rates, with concomitant reductions in overall health care costs (Casey et al., 2011; J. B. Gordon et al., 2007). However, little research has directly examined the effect of comprehensive care models on families. A full understanding of how tertiary care center-based comprehensive care addresses CMC family needs allows such programs to gauge the full impact of this innovative model of service delivery.

In 2006, Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH) created the Medical Home Clinic for Special Needs Children (MHCL), offering multidisciplinary care oversight and tertiary care center-based care coordination for CMC (Tanios et al., 2009). By complementing existing care that is provided by primary and tertiary care services, the MHCL aims to help CMC and families experience comprehensive care consistent with the medical home concept as defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics (Casey et al., 2011; Pediatrics, 2002). Many MHCL patients have technology dependence, functional limitations, and severe neurodevelopmental disabilities that are static in nature. Prior analyses demonstrated a reduction in hospitalizations and overall health care costs after 12 months of enrollment in the MHCL (Casey et al., 2011). Despite the financial impact of the MHCL, the potential changes in parental perspectives on health care delivery and outcomes have not previously been described. The objective of this study was to evaluate parent-reported outcomes after 12 months of the child’s enrollment in the MHCL, which would allow multiple points of contact to enable sufficient experience with the MHCL. This study examined parent health, child health and functioning, family stress, and overall satisfaction with clinical services. We hypothesized that parents would report decreased stress, improved health, and improved family functioning after 12 months of enrollment.

Methods

This is a pre-post cohort study of parent/family (henceforth referred to as parent) caregivers of children enrolled at a tertiary care center-based, comprehensive care, outpatient service for CMC.

Medical Home Clinic for Special Needs Children (MHCL)

The MHCL was started in August 2006 at ACH to address the needs of infants and children with multiple specialty care needs and frequent hospitalizations. This outpatient service provides team-based care and care coordination to ensure necessary medical, nutritional, and developmental care. Providers include pediatricians, nurses, nutritionist, speech therapist, social workers, and child psychologist. The team composition was influenced by the high prevalence of nutritional and feeding disorders. Eligibility criteria include a referral from primary care provider or specialist, ≥2 serious chronic conditions, and ongoing management by ≥2 pediatric subspecialists. Each patient is assigned a nurse coordinator who is available for telephone consultation during daytime hours, coordinates appointment, discusses acute care issues, and maintains an updated care plan. As children from throughout the state of Arkansas receive care at the MHCL, all children continue seeing their community-based primary care provider (PCP) for preventive care and immunizations, with varying levels of co-management with the MHCL. A previously published report (Berry, Agrawal, et al., 2011) and additional chart review found overall patient characteristics of 59% male, 73% preterm infants, a mean of 3.4 (sd 2.0) specialists seen, 64% with technology assistance such as gastrostomy tube or tracheostomy, and 2.6 (sd 2.4) hospitalizations in the past year. MHCL service eligibility criteria and patient characteristics are generally similar to comprehensive care services for CMC at other children’s hospitals, specifically by number of chronic conditions, involvement with multiple specialists, the presence of complex chronic conditions, and technology assistance; MHCL children tend to be younger due to many direct referrals from the neonatal intensive care units (Berry, Agrawal, et al., 2011).

Study subjects and enrollment

Parents of MHCL patients were prospectively approached for potential study enrollment at the initial MHCL visit. Eligibility criteria included (1) the child being home from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) ≥6 months, to avoid potential NICU-related readmissions and to allow sufficient post-NICU experience with the MHCL; (2) not seen previously by a MHCL attending in other ACH clinics. Clinic staff identified eligible study participants through initial patient appointments. Upon family arrival in the clinic, a research associate explained the study and enabled parents to provide informed consent. The research associate then conducted an in-person interview in the clinic while the family was not seeing a provider. Parents were given the option of being sent home with the survey and a self addressed stamped envelope. The 12-month follow-up survey contained scales and questions used in the initial survey, with additional questions examining MHCL care experience. Families with a twelve-month follow-up appointment were approached for the follow-up survey upon clinic arrival. If there was no timely scheduled appointment, the family received a letter in the mail reminding them of the study, accompanied by a written copy of the survey that parents were asked to complete and mail back in a self-addressed stamped envelope. Up to six follow-up phone calls were made by study staff if the survey was not returned within three weeks. Compensation at the time of both surveys included a stuffed animal for the child and a tote bag to the parent.

Because multiple outcome measures were assessed, a single generic sample size calculation was conducted. A sample size of at least 100 study subjects with completed pre and post data was calculated to be sensitive to a 0.40 standard deviation unit change (improvement or worsening) in outcomes at alpha=.05, power=.80. Thus, study subjects were enrolled prospectively at initial visit until at least 100 study subjects completed the 12-month follow-up. At that time enrollment was closed, with 12-month follow-up surveys continuing. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Study Variables

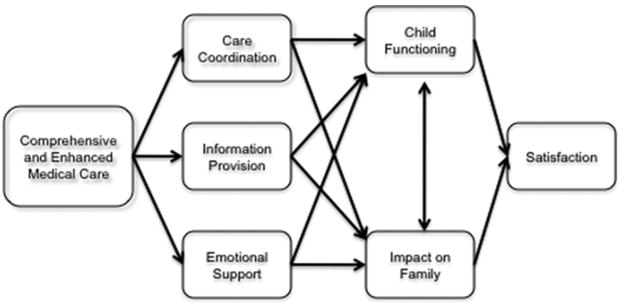

A framework for health care delivery in the MHCL [Figure 1] was developed from existing health care frameworks for chronic care and CSHCN (Antonelli, Stille, & Freeman, 2005; Bodenheimer, Wagner, & Grumbach, 2002; Perrin et al., 2007). Our framework specifies essential components of comprehensive and enhanced medical care, particularly care coordination, provision of information, and emotional support. The components were felt to lead to significant improvements in parent perceptions of child and family health and functioning. Successful family outcomes then result in higher family satisfaction with health care. Study outcome variables and the analytic framework were organized accordingly.

Figure 1.

Framework for health care delivery in the medical home clinic.

Health Care Delivery variables were defined by questions on experiences with care coordination, a written care plan, receipt of specific information related to the child’s condition, and experiences with support on emotional needs. Study questions were adapted from prior surveys developed by New England SERVE that were specifically designed to measure health care experiences of families of CSHCN.

Parent Outcomes were measured by previously validated scales, each scored according to previously cited literature, including:

Functional Status RII Measure (child functioning) (Kromer, Prihoda, Hidalgo, & Wood, 2000; Stein & Jessop, 1990): The 14-item short-version scale measures a child’s capacity to perform age-appropriate roles and tasks in a variety of domains such as communication, mobility, mood, energy, sleeping, and eating.

Family Support Scale (FSS) (Black et al., 2011; Burke & Alverson, 2010; Nolan, Orlando, & Liptak, 2007; Pediatrics, 2011): The six-item version examines parental satisfaction with support received from people, such as spouse, friends, and child care workers.

Impact on Family Scale (J. Gordon, 2009; Huang, Kogan, Yu, & Strickland, 2005; Witt, Gottlieb, Hampton, & Litzelman, 2009): The 15-item scale used for ease of administration within the broader survey measures the effect of the child’s chronic illness on the family. The parent rates each item on a 4-point Likert scale that ranges from (1) ‘strongly agree’ to (4) ‘strongly disagree’. The Social subscale examines items related to travel and mobility; the Personal subscale examines items related to personal time and stress level.

SF-12 (Health-Related Quality of Life) (Malouin & Merten, 2010; Peikes, Dale, Lundquist, Genevro, & Meyers, 2011): A 12-item scale that measures parents’ health status. The physical subscale examines physical abilities and regular daily activities; the mental health subscale examines emotional feelings and sense of energy level. Higher scores represent better health status.

Satisfaction was measured by questions regarding the parent’s satisfaction with doctors/nurses and primary care received. The 12-month follow-up survey also examined experiences and overall satisfaction with the MHCL.

Descriptive variables include parent gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, family income, and having another child with special needs.

Analytic plan

Descriptive data were provided for respondents at 12 months unless otherwise noted. Study outcomes were tested with a pre-post research design, examining changes in study scale ratings from enrollment to 12 months. In paired tests, each caregiver acts as his or her own control, thus no additional adjustment is needed for any confounding variables. Paired analyses included t-tests for continuous variables and McNemar test for categorical data. Additional descriptive analyses were performed for variables that were obtained solely at the 12 month visit. Family outcomes analyses were stratified to examine specific subgroups of interest: hospitalized in the prior six months; number of specialists seen in the prior six months (dichotomized at the median); presence of another child with special health care needs in the household; and medical equipment need.

Results

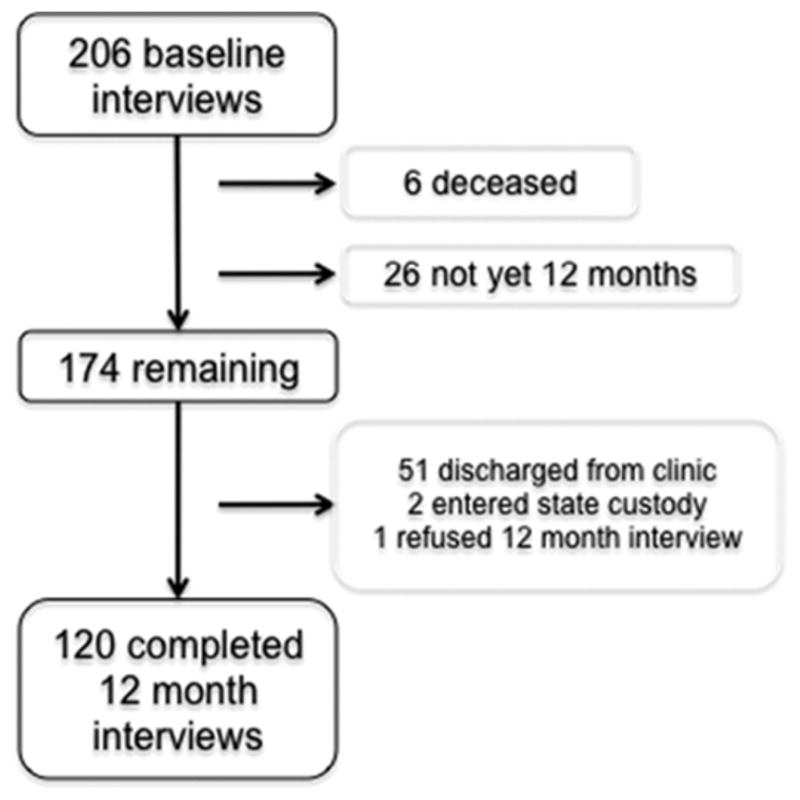

Of 654 patients who came for an initial visit to the MHCL between October 2007 and April 2011, the parents of 276 were potentially eligible for study enrollment. There were three refusals, 21 who did not complete the baseline interview, and 46 parents who were missed due to research staff unavailability, leaving 206 (75%) completing baseline interviews. Study subject follow-up can be found in Figure 2. Six patients died before the 12-month follow-up and 26 were not yet 12 months at the time of this analysis, leaving 174 parents of children eligible for follow-up. Of that group, 38 children did not attend a 12 month follow-up visit and could not be reached at home after repeated attempts, 13 were discharged from the clinic due to being judged not to require ongoing services, 2 children were removed from parental custody, and 1 parent refused further study involvement, leaving 120 parents completing 12 month interviews (69.0% of parents eligible for follow-up).

Figure 2.

Study enrollment.

Demographics of parent respondents at the 12-month visit can be found in Table 1. Almost all respondents (90%) were the biological parent. Most parents (84%) were female; 63% were white/Caucasian. About half of parents were married (53%) and high school graduates (51%). At 12 months, 36% were employed; this was higher than at baseline (31%), but the increase followed a non-significant trend by paired analysis (p=.22). Half of respondents reported income <$20,000/year and one-fourth reported having another child with special health care needs, with the range between 1 and 5 additional children. Parents reported that their children saw a median of 5 other specialists (interquartile range 3, 7) in the past six months. At follow-up, 41% of parents reported their child had been hospitalized at least once in the prior 6 months, a decrease from 60% at baseline (p<.001). Over two-thirds of parents (71%) reported their child depended on medical equipment for activities of daily living.

Table 1.

Demographics of Parent Respondents at 12 Month Visit (n=120).

| % | |

|---|---|

| Female gender | 84% |

| White/Caucasian | 63% |

| Married | 53% |

| Biological parent | 90% |

| High school graduate | 51% |

| Currently employed | 36% |

| Income <$20,000/year | 48% |

| Has another child with special needs | 25% |

Health Care Delivery outcomes are found in Table 2. The proportion of parents who reported needing help with care coordination declined from 78% at baseline to 31% at 12 months (p<.001). The proportion of parents needing help specifically with school care coordination declined from 81% to 42% (p<.001). The proportion of parents who reported their child had a written care plan rose from 53% to 85% (p<.001). No changes were seen in parents reporting having received information regarding family support or information on current research. No changes were seen in families reporting that the medical team helped understand the child’s emotional needs or show concern about the impact of the health condition on the family.

Table 2.

Health Care Delivery Outcomes (n=120).

| Baseline (se), % | 12 month (se), % | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Need help with care coordination | 78.3% (4.6) | 31.3% (5.2) | <.001 |

| Child has a written care plan | 52.9% (4.6) | 84.9% (3.3) | <.001 |

| Receive info about family support | 45.7% (5.2) | 55.3% (5.2) | .14 |

| Receive info about current research | 37.5% (4.8) | 33.7% (4.7) | .52 |

| Care team helps with understanding child’s emotional needs | 54.8% (5.2) | 49.4% (5.2) | .46 |

| Care team shows concern about impact of health on family | 62.7% (4.5) | 62.7% (4.5) | 1 |

Parent Outcomes are found in Table 3. Non-significant trends were found between baseline and 12 month ratings of the Child Functioning (76.2 versus 76.6, p=.76), including all stratified analyses. Parents reported a marginally significant trend in the Impact on Family Social subscale (23.2 versus 26.0, p=.06). No difference was seen on the Personal subscale. In stratified analyses, the rise in the Social subscale was notable for marginally significant trends for children with medical equipment use (22.9 versus 26.3, p=.09), parents without any other children with special needs (23.6 versus 27.2, p<.06), and children who saw at least 4 specialists in the past year (22.8 versus 26.7, p=.07).

Table 3.

Parent Outcomes (n=120).

| Baseline (se) | 12 month (se) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Status RII (Child Functioning) Scale | 76.2 (1.6) | 76.6 (1.3) | .76 |

| Impact on Family: Social | 23.2 (.48) | 26.0 (1.5) | .06 |

| Impact on Family: Personal | 14.6 (.34) | 14.7 (.39) | .84 |

| Parent Support Scale | 3.6 (.09) | 4.4 (.50) | .13 |

| SF-12 Health-Related Quality of Life, physical subscale | 49.1 (.93) | 46.4 (1.1) | <.01 |

| SF-12 Health-Related Quality of Life, mental subscale | 45.4 (.97) | 45.5 (.93) | .92 |

Scores on Parent Support Scale increased, but not significantly (3.6 versus 4.4, p=.13). Among subgroups with non-significant trends were children who were not hospitalized (3.5 versus 4.8, p=.13), no other children with special needs in household (3.7 versus 4.7, p=.13), and no equipment needs (3.6 versus 6.0, p=.16). Parents reported a significant decrease in the SF-12 physical subscale (49.1 versus 46.4, p<.01) but no changes in the mental subscale (45.4 versus 45.5, p=.92). The decrease on the physical subscale was particularly strong for parents with children who had medical equipment need (49.2 versus 46.1, p<.01) and even more so for parents who had another child with special needs (49.2 versus 42.5, p<.001).

Satisfaction measures can be found in Table 4. Parents reported overall high levels of satisfaction with choices of doctors and nurses, with an increase between baseline and 12 months that was marginally significant (90.0% versus 96.7%, p=.06). The increase in satisfaction with primary care was not significant (70.8% versus 76.7%, p=.26).

Table 4.

Parent Reported Satisfaction (n=120).

| Baseline | 12 month | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied with overall choice of doctors/nurses | 90.0% (3.0) | 96.7% (1.6) | .06 |

| Satisfied with primary care received | 70.8% (4.2) | 76.7 (3.9) | .26 |

At the 12-month follow-up, 97% of parents rated the MHCL staff as usually/always available when they had concerns about the child’s medical condition and 87% responded that MHCL staff usually/always showed concern about the impact of the child’s health condition on the family. Most parents (87%) reported usually/always receiving specific information needed from MHCL staff, and 94% responded feeling like a partner in the care of the child. Relatively fewer parents (68%) responded that MHCL staff helped the family member understand the child’s emotional needs.

Discussion

The presence of a complex and chronic health condition can have profound negative impact on the economic and social health of families (Kuo, Cohen, et al., 2011). We have previously reported significant reductions in overall health care costs for Medicaid-enrolled children in the MHCL, specifically by reducing inpatient utilization even with modest increases in outpatient utilization (Casey et al., 2011). Our current study found that after twelve months of enrollment in the MHCL, families reported high satisfaction with MHCL services and significant improvements in receipt of care coordination. We found less improvement in the domain of information receipt, although the proportions of families at 12 months reporting a written care plan (85%) and receiving specific information needed from MHCL staff (87%) were high. Given prior findings of reduced inpatient admissions and overall costs for enrolled children (Casey et al., 2011), we suggest that care coordination and information receipt are the likely pathways for potential cost savings for this group of vulnerable children. System of care navigation, which care coordination and information receipt directly address, has been described as the biggest concern for parents of children with special health care needs (Ray, 2002).

Despite enhanced care coordination, health care accessibility, and improved information receipt, only half of parents reported help with understanding the child’s emotional needs, and no changes were found on meeting family emotional needs over 12 months. Our service has a social worker routinely address family needs at each visit; in more recent years, a pediatric psychologist has also been available for consultation during visits. However, we also found limited impact on parent-reported child and family functioning. Improvement on the Impact on Family Social subscale was seen only in the subgroups of parents who have children seeing multiple specialists, having equipment needs, and having no other child with special needs. The findings suggest modest respite is difficult to come by if there are other CSHCN in the household that may present competing demands.

Our findings may be in part due to immutable health factors of this extremely vulnerable population and the natural progression of disease in a population that has experienced increasing rates of survival (Tennant, Pearce, Bythell, & Rankin, 2010). The decline in the caregiver physical scale of the SF-12 is striking, particularly within the subgroup of parents who have additional CSHCN. The decline in physical abilities may reflect ongoing, previously unreported physical stressors that result over time, a lack of respite (Macdonald & Callery, 2008), or the cumulative care burden, including persistent caregiving demands (Raina et al., 2005). “Chronic sorrow” that results from persistent care needs and ongoing reminders of the loss of the “perfect” child can result in a pathologic grief-like state if not properly recognized and addressed (J. Gordon, 2009).

We suggest that care coordination and enhanced information in the medical setting may be insufficient to address the pervasive emotional and physical needs of families of CMC. Medical care is only a portion of the system of care that families depend on in order to maximize the functioning of the child and family (Pediatrics, 2011; Perrin et al., 2007; Ray, 2002; Taylor, Lake, Nysenbaum, Petersen, & Meyers, June 2011), and fundamental misunderstandings exist among some providers on how to address family needs (Leiter, 2004; Liptak & Revell, 1989; MacKean, Thurston, & Scott, 2005). Principles of family-centered care, such as shared decision making, screening tools, and use of community resources (Kuo, Houtrow, et al., 2011) can lead to improved health and functioning of the child with special health care needs (Antonelli et al., 2005; Dunst, Trivette, & Hamby, 2007; Kuhlthau et al., 2010). A short psychosocial family member screening has been shown to increase referrals to community supports in the primary care setting (Garg et al., 2007). Further research should identify mutable factors outside of the clinical setting that can lessen the physical burden on families, meet family emotional needs, and further impact health care costs and utilization. The high satisfaction reported by parents in the MHCL suggests that even as families are pleased with their care experiences, they may also not be cognizant of what additional services may ameliorate their burden further. Such expectations should be explored in future studies.

There are a number of strengths of our study. We have previously demonstrated reduction in inpatient utilization and overall health care costs, and tertiary care center-based comprehensive services have attracted increasing attention for their potential for improving outcomes and achieving cost savings (Agrawal & Antonelli, 2011). We used previously validated scales to assess a range of family outcomes. The use of paired analyses through a pre-post analytic design enables examination of changes in outcomes on the family level, although paired analyses limits findings to the specific group of study subjects. The major limitation of our findings is that it is a study of one service model at a specific children’s hospital, without a control group or random assignment, and subject to study maturation, thus at best should be considered a preliminary study. Our findings could vary by patient population, clinical service, or hospital location. Our findings are parent reported without any external validation of results. The pre-post design of our study could be subject to a regression to the mean artifact, although we have not detected large improvements in health and functioning to suggest such a bias. Our study measures have not be subjected to validity testing when used within a long survey, nor has test-retest reliability been examined in the manner we utilized the study. We have no data on families that dropped out of our study prematurely. Due to exclusion criteria, our study results may not be representative of all patients in our clinic or children with medical complexity who would benefit from a comprehensive care service; specifically, we enrolled older children who remained enrolled in our service after 12 months. However, the study criteria likely identified children with the highest needs and costs whose families are most in need of intervention.

It is important to reiterate that the MHCL by itself does not provide a medical home; rather, our services complements existing services so that the child and family experiences comprehensive care that is consistent with a medical home. We emphasize that the key for families of CMC is to receive overall care that is consistent with the medical home concept, and that the actual locus of care is not the determining factor of whether a child receives a medical home. In the case of the MHCL, children have to be referred to our service by a PCP or a specialist, and almost all PCPs provide consent for MHCL co-authority to provide referral, equipment and ancillary service authorizations, confirming a desire for co-management.

Conclusions

A comprehensive care model for CMC can improve care coordination and information receipt by families. However, we did not find improved parent outcomes, and our findings suggest that parent physical health may continue to worsen over time. Future studies should closely identify family stressors and the mutable factors that can improve parental outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kuo was supported by the Marion B. Lyon New Scientist Award and by grants 8 UL1 TR000039-04 and 8 KL2 TR000063-04 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The funding bodies had no role in design or conduct of the study; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CMC

Children with Medical Complexity

- CSHCN

Children with Special Health Care Needs

Footnotes

The study findings were presented in part at the 2011 Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, Denver, CO.

References

- Agrawal R, Antonelli RC. Hospital-based programs for children with special health care needs: implications for health care reform. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(6):570–572. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli R, Stille C, Freeman L. Enhancing collaboration between primary and subspecialty care providers for children and youth with special health care needs. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Children and Human Development; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Berman S, Rannie M, Moore L, Elias E, Dryer LJ, Jones MD., Jr Utilization and costs for children who have special health care needs and are enrolled in a hospital-based comprehensive primary care clinic. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e637–642. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JG, Agrawal R, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Risko W, Hall M, Srivastava R. Characteristics of Hospitalizations for Patients who Utilize a Structured Clinical-Care Program for Children with Medical Complexity. J Pediatr. 2011;159(2):284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Feudtner C, Neff J. Hospital Utilization and Characteristics of Patients Experiencing Recurrent Readmissions Within Children’s Hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black NM, Kelly MN, Black EW, Sessums CD, DiPietro MK, Nowak MA. Family-Centered Rounds and Medical Student Education: A Qualitative Examination of Students’ Perceptions. Hosp Pediatr. 2011;1(1):24–29. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2011-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RT, Alverson B. Impact of children with medically complex conditions. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):789–790. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KH, Casey PH, Lyle RE, Bird TM, Fussell JJ, Robbins JM. Increasing Prevalence of Medically Complex Children in US Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):638–646. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey PH, Lyle RE, Bird TM, Robbins JM, Kuo DZ, Brown C, Burns K. Effect of Hospital-Based Comprehensive Care Clinic on Health Costs for Medicaid-Insured Medically Complex Children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(5):392–398. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Friedman JN, Mahant S, Adams S, Jovcevska V, Rosenbaum P. The impact of a complex care clinic in a children’s hospital. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36(4):574–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Jovcevska V, Kuo DZ, Mahant S. Hospital-based comprehensive care programs for Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN): A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(6):554–561. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Bhagat SKM, Simon TD, Srivastava R. Children with medical complexity: An emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Hamby DW. Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(4):370–378. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Butz AM, Dworkin PH, Lewis RA, Thompson RE, Serwint JR. Improving the management of family psychosocial problems at low-income children’s well-child care visits: the WE CARE Project. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):547–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose R. Complications of a medically complicated child. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(4):301–302. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-4-200308190-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J. An evidence-based approach for supporting parents experiencing chronic sorrow. Pediatr Nurs. 2009;35(2):115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JB, Colby HH, Bartelt T, Jablonski D, Krauthoefer ML, Havens P. A tertiary care-primary care partnership model for medically complex and fragile children and youth with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):937–944. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.10.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Kogan MD, Yu SM, Strickland B. Delayed or forgone care among children with special health care needs: an analysis of the 2001 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(1):60–67. doi: 10.1367/A04-073R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A, Golnik A, Cady R. A medical home center: specializing in the care of children with special health care needs of high intensity. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(5):633–640. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzner TS, Rabbitt LA, Chang RK. Benefits of Care Coordination for Children with Complex Disease: A Pilot Medical Home Project in a Resident Teaching Clinic. J Pediatr. 2010;156(6):1006–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromer ME, Prihoda TJ, Hidalgo HA, Wood PR. Assessing quality of life in Mexican-American children with asthma: impact-on-family and functional status. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25(6):415–426. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.6.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlthau K, Bloom S, Van Cleave J, Romm D, Klatka K, Homer C, Perrin JM. Evidence for family-centered care for children with special health care needs: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(2):136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Casey PH. A National Profile of Caregiver Challenges Among More Medically Complex Children with Special Health Care Needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(6):1020–1026. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo DZ, Houtrow AJ, Arango P, Kuhlthau KA, Simmons JM, Neff JM. Family-Centered Care: Current Applications and Future Directions in Pediatric Health Care. Matern Child Health J. 2011;16(2):297–305. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0751-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo DZ, Robbins JM, Burns KH, Casey PH. Individual and Practice Characteristics Associated with Physician Provision of Recommended Care for Children with Special Health Care Needs. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50(8):704–711. doi: 10.1177/0009922811398961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter V. Dilemmas in sharing care: maternal provision of professionally driven therapy for children with disabilities. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(4):837–849. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Revell GM. Community physician’s role in case management of children with chronic illnesses. Pediatrics. 1989;84(3):465–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald H, Callery P. Parenting children requiring complex care: a journey through time. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34(2):207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKean GL, Thurston WE, Scott CM. Bridging the divide between families and health professionals’ perspectives on family-centred care. Health Expect. 2005;8(1):74–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2005.00319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouin RA, Merten SL. Measuring Medical Homes: Tools to Evaluate the Pediatric Patient- and Family-Centered Medical Home. National Center for Medical Home Implementation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Myers K. Profile of medical charges for children by health status group and severity level in a Washington State Health Plan. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan KW, Orlando M, Liptak GS. Care coordination services for children with special health care needs: are we family-centered yet? Fam Syst Health. 2007;25(3):293–306. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):184–186. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Parent-Provider-Community Partnerships: Optimizing Outcomes for Children With Disabilities. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):795–802. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peikes D, Dale S, Lundquist E, Genevro J, Meyers D. Building the evidence base for the medical home: what sample and sample size do studies need? Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin JM, Romm D, Bloom SR, Homer CJ, Kuhlthau KA, Cooley C, Newacheck P. A family-centered, community-based system of services for children and youth with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):933–936. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.10.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina P, O’Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, Wood E. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e626–636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LD. Parenting and Childhood Chronicity: making visible the invisible work. J Pediatr Nurs. 2002;17(6):424–438. doi: 10.1053/jpdn.2002.127172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, Stone BL, Sheng X, Bratton SL, Srivastava R. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R, Stone BL, Murphy NA. Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52(4):1165–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RE, Jessop DJ. Functional status II(R). A measure of child health status. Med Care. 1990;28(11):1041–1055. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanios AT, Lyle RE, Casey PH. ACH medical home program for special needs children. A new medical era. J Ark Med Soc. 2009;105(7):163–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EF, Lake T, Nysenbaum J, Petersen G, Meyers D. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, editor. Coordinating care in the medical neighborhood: critical components and available mechanisms. Rockville, MD: Jun, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant PW, Pearce MS, Bythell M, Rankin J. 20-year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;375(9715):649–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61922-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt WP, Gottlieb CA, Hampton J, Litzelman K. The impact of childhood activity limitations on parental health, mental health, and workdays lost in the United States. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]