Abstract

Background:

Patients with refractory asthma frequently have elements of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) with potential aspiration contributing to their poor control. We previously reported on a supraglottic index (SGI) scoring system that helps in the evaluation of LPR with potential aspiration. However, to further the usefulness of this SGI scoring system for bronchoscopists, a teaching system was developed that included both interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility.

Methods:

Five pulmonologists with expertise in fiber-optic bronchoscopy but novice to the SGI participated. A training system was developed that could be used via Internet interaction to make this learning technique widely available.

Results:

By the final testing, there was excellent interreader agreement (κ of at least 0.81), thus documenting reproducibility in scoring the SGI. For the measure of intrareader consistency, one reader was arbitrarily selected to rescore the final test 4 weeks later and had a κ value of 0.93, with a 95% CI of 0.79 to 1.00.

Conclusions:

In this study, we demonstrate that with an organized educational approach, bronchoscopists can develop skills to have highly reproducible assessment and scoring of supraglottic abnormalities. The SGI can be used to determine which patients need additional intervention to determine causes of LPR and gastroesophageal reflux. Identification of this problem in patients with refractory asthma allows for personal, individual directed therapy to improve asthma control.

Refractory1 or severe asthma has a high associated morbidity and economic cost.2,3 Even with asthma guideline therapy,4 up to 50% of patients have asthma that is not well controlled or is refractory to treatment.5 Fiber-optic bronchoscopy has been shown to be useful in evaluating both the upper and lower airways of patients with refractory asthma, which allows for better phenotyping of these individuals and, thus, specific patient-oriented therapy.6 This approach has led to improved outcomes.6

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) can occur in association with gastroesophageal reflux (GER) or independent from GER. LPR can be injurious to the supraglottic area and lower airway, with potential aspiration. To better evaluate potential supraglottic injury resulting from LPR, a supraglottic index (SGI) was developed and used to give objective, applicable, and reproducible data for use in patients with asthma.6 To keep consistency in that study, one individual scored the SGI. However, for clinical applicability, a teaching method for bronchoscopists to learn the SGI scoring technique was developed in concert with documentation that interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility was valid. This subsequent study demonstrates these points.

Materials and Methods

National Jewish Health’s Institutional Review Board approval (HS2477 and HS2639) was obtained to use these prospective clinical data for publication. The SGI is a numeric scoring system that allows for an objective grading system to quantify the amount of supraglottic abnormality present. The purpose of this study was to determine if the five individual scorers could have reproducible results grading the same photos as the control reader.

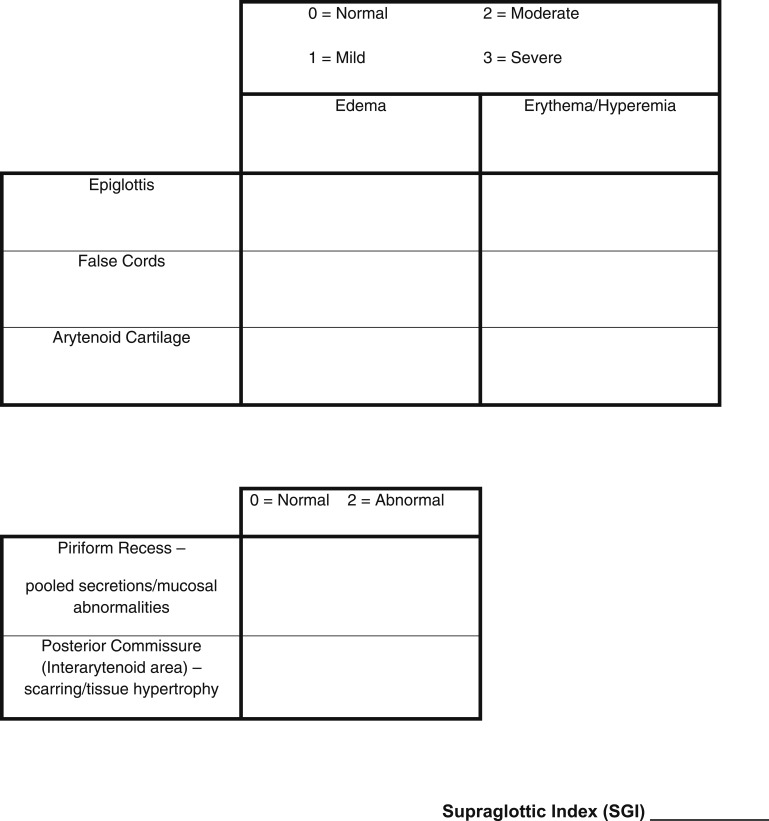

Supraglottic Index

Three supraglottic structures (epiglottis, false cords, and arytenoids) are scored for the amount of edema (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) that is present. In addition, these structures are evaluated for the amount of erythema or hyperemia by using the same numeric scale from 0 to 3. The posterior commissure (interarytenoid area) and the piriform recesses (piriform sinuses) are scored as normal = 0 or abnormal = 2. The score for the SGI ranges from 0 to 22 (Fig 1, scoring sheet).

Figure 1.

Supraglottic index scoring sheet.

Teaching Program

Five pulmonologists with expertise in fiber-optic bronchoscopy, but novice to the SGI, were recruited for this study. All five were trained in bronchoscopy using American Board of Internal Medicine guidelines and were board certified in pulmonary medicine. Three pulmonologists recently completed their pulmonary fellowships. One of the two senior pulmonologists was recruited from private practice; the other had a 35-year academic career. We believed that learning this technique would require multiple sessions before interobserver and intraobserver validity would be meaningful. Prior to the first scoring session, a 1-h training lecture with the use of photographs and video recordings occurred. During this session, the supraglottic index was described in detail, and each of the anatomic areas to be graded was reviewed. Examples of normal, mild, moderate, and severe edema and erythema/hyperemia for the epiglottis, false cords, and arytenoids were provided. Photographs of normal and abnormal posterior commissures and piriform recesses were also reviewed. Five cases were provided, and each physician graded them and compared their scores with the control reader.

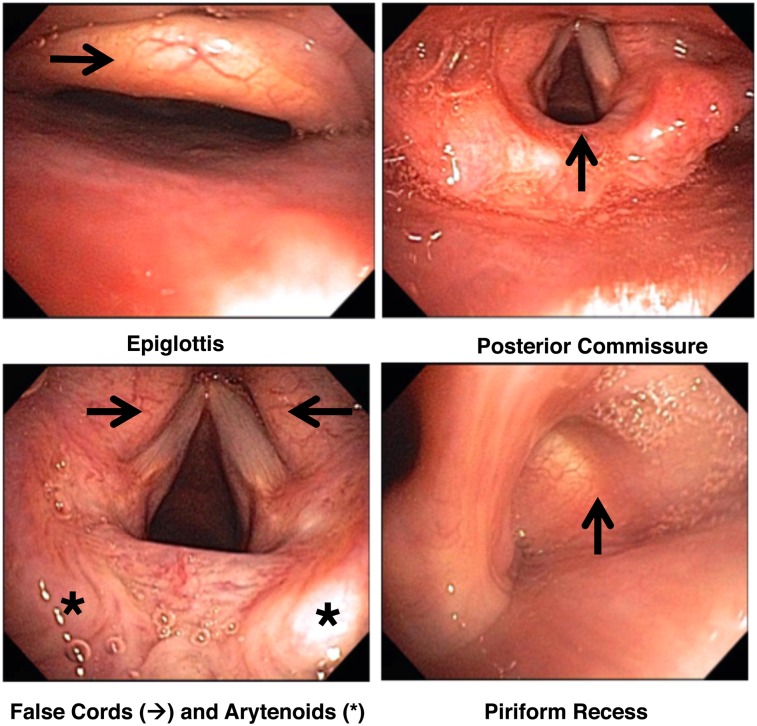

Scoring session 1 consisted of 50 patients with four photographs each of the supraglottic areas; these were provided to the readers on a flash drive. Readers had the ability to adjust the photographic size using the zoom application on their computer. Figure 2 demonstrates an example of photographs used in grading the SGI. In this patient, the epiglottis received a score of 1 for edema and 1 for hyperemia; the false cords: 2 for edema and 3 for hyperemia; the arytenoids: 3 for edema and 3 for erythema; the posterior commissure: 2; and the piriform recess: 2. The sum of these makes an SGI score of 17. It should be noted that the true cords can be involved in patients with refractory asthma, but this is not part of our scoring system. After session 1 scoring, the readers were given the control reader’s calculations so scores could be compared and discussed.

Figure 2.

Example of the supraglottic areas to score.

Session 2 consisted of the photos used in session 1 being randomly shuffled, and the physicians again calculated the SGI for 50 patients. Scores were reviewed, and readers again had reference to the control reader’s SGI values.

In session 3, a new set of 50 different patients’ supraglottic photographs were reviewed. These scores were compared with the control score. Readers were asked to rescore those SGI calculations that varied by four or more from the control reader. In addition, readers were asked to rescore if they had an SGI ≥ 10 and control < 10 or SGI < 10 and control > 10. The reason for using the SGI cut point of 10 is that an SGI ≥ 10 was shown in a previous study to be a threshold value for the presence of LPR.6

Session 4 consisted of the photographs in session 3 being randomly shuffled and rescored. Individual scores were discussed and reviewed by the control reader with the other readers. Special attention was given to scores that varied by four or more points from the control reader and those discordant with the control SGI value of 10.

Interreader and Intrareader Validity

After the previously described sessions, 30 new patient photographs of the supraglottic area were distributed to the five learners. The distribution of SGI scores was 0 to 9 (nine patients), 10 to 16 (13 patients), and 17 to 22 (eight patients).

We assessed the relationship between scores for each novice reader and the control reader using a form of regression that can account for measurement error in the X variable (the scores of the control reader).7,8 We conducted these analyses using R.9 Using an SGI cutoff of 10 units,6 we estimated κ between each new reader and the control reader (SAS/STAT software package, version 9.2 of the SAS System for Windows XP; SAS Institute Inc). We defined the critical significance level α to be 0.05.

Results

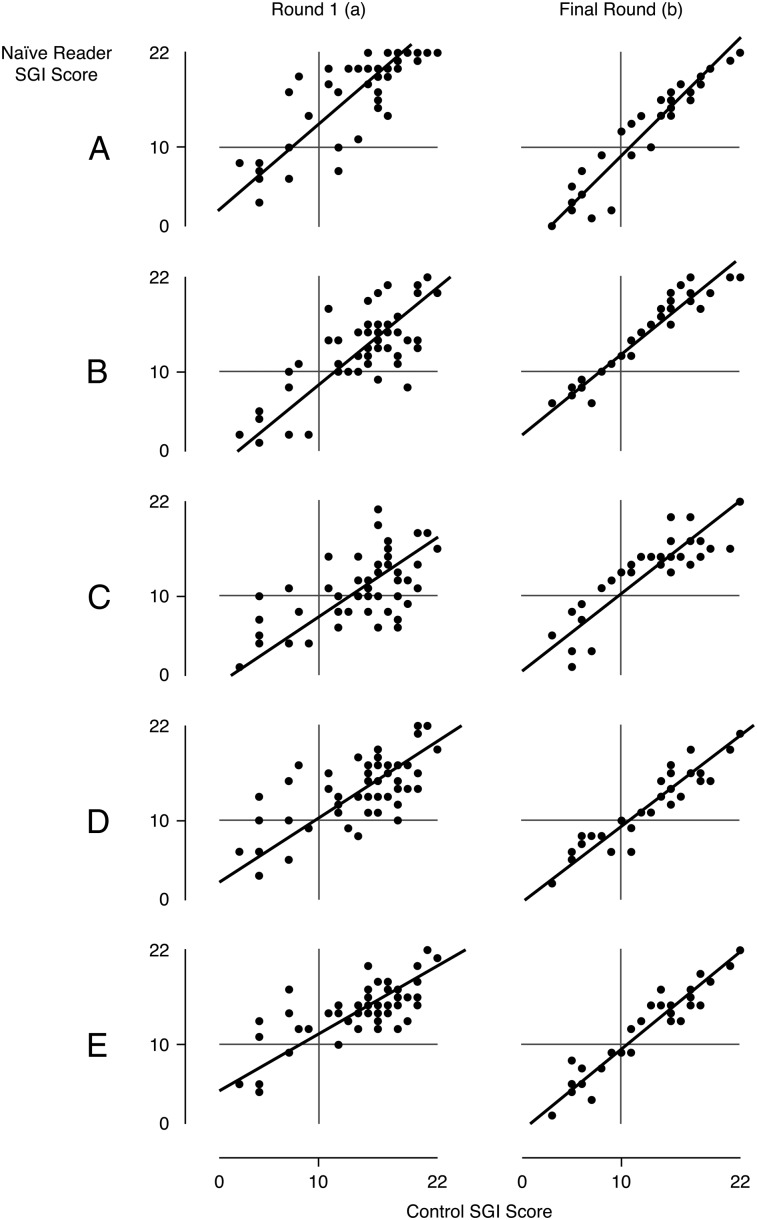

After session 1, there was expected variability among all naive readers compared with the control reader (regression R2 = 51%; range, 35%-65%). Figure 3A demonstrates the comparison of the naive readers vs the control reader of session 1 for SGI scoring. In the final scoring session, there was a marked decrease in variability between the naive readers and the control reader (regression R2 = 86%; range, 75%-92%) (Fig 3B).

Figure 3.

The vertical axis represents the readers’ SGI scoring, and the horizontal axis represents the control scores. After the first training session there was discordance between readers and control (regression R2 = 51%; range, 35%-65%) (column a). By the final session very good concordance was achieved (regression R2 = 86%; range, 75%-92%) (column b). SGI = supraglottic index.

Table 1 demonstrates the estimate of the amount of fixed (intercept) and proportional (slope) bias at the final testing session. A perfect SGI scoring between each naive reader and control reader would be represented by an intercept of zero and a slope of 1. If the CI for the intercept includes zero, the intercept is consistent with zero. If the CI for the slope includes 1, then the intercept is consistent with 1. For naive readers C through E, both the fixed and proportional biases are tightly linked to the control reader. A and B are acceptably linked to the control reader, with A overall reading slightly under the reader by 3.5 units and B slightly over by 2 units.

Table 1.

—Relationships Between Scores From Five Naive Readers and the Control Scores

| Reader | Intercepta | Slopeb |

| A | −3.5 | 1.2 |

| −5.6 to −1.7 | 1.1 to 1.4 | |

| B | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| 0.6 to 3.4 | 0.9 to 1.1 | |

| C | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| −2.0 to 2.7 | 0.8 to 1.2 | |

| D | −0.3 | 1.0 |

| −2.2 to 1.3 | 0.8 to 1.1 | |

| E | −0.8 | 1.0 |

| −2.5 to 0.6 | 0.9−1.2 |

The intercept represents the amount of fixed bias, the naive reader score when the control score is zero.

The slope represents the amount of proportional bias, the change in naive reader score when the control score changes by 1 unit.

Additionally, for the final scoring for SGI < 10 and ≥ 10, the interreader agreement of the SGI with the control reader is exceptional (defined as κ of at least 0.81).10 Table 2 demonstrates agreement with κ between 0.83 and 0.92. Furthermore, the five κ values are statistically different from zero (P < .001) but similar to each other (P = .94).

Table 2.

—Agreement of Naive Readers With Control Readers for SGI Score < 10 and ≥ 10

| Reader | κ | 95% CI |

| A | 0.92 | 0.78−1.00 |

| B | 0.83 | 0.61−1.00 |

| C | 0.83 | 0.61−1.00 |

| D | 0.85 | 0.65−1.00 |

| E | 0.85 | 0.65−1.00 |

A κ value of ≥ 0.81 denotes that the strength of agreement is very good.11

For the measure of intrareader consistency, Reader E was arbitrarily selected to rescore the final test 4 weeks later. The κ between the two scoring tests of reader E was 0.93, with a 95% CI of 0.79 to 1.00.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop a teaching technique that results in reproducibility for evaluation and scoring of abnormalities in the supraglottic area. Originally we were interested in phenotyping refractory asthma by bronchoscopic evaluation of the upper and lower airways so as to be able to direct personalized therapy to this difficult-to-treat group of patients.6 One of the largest phenotypes was represented by those with LPR (perhaps incorrectly termed GER in that study). We developed the supraglottic index to help in the phenotyping of these patients with refractory asthma as to supraglottic abnormalities that would be consistent with LPR.6 Since classic GER may be intermittent, the standard GER tests may give false-positive or false-negative results. Additionally, GER may occur, but it is not always associated with LPR, and, thus, no potential aspiration develops. The supraglottic index gives a history of what occurs with intermittent or continuous irritation of this area over time. Thus, we feel that LPR with potential aspiration may be better evaluated by the SGI than standard GER studies.

There are several methods and scoring systems that have been used to define and quantify the degree of upper airway abnormalities.11,12 Although there are many studies describing supraglottic abnormalities, an accurate, simple, and reproducible method to access and score supraglottic abnormalities, particularly in asthma, had not existed.

In the general reflux finding score (RFS) by Belafsky et al,11 eight areas/items were evaluated with a variable grading scale from 0 to 4. These included subglottic edema, ventricular edema, erythema-hyperemia, vocal fold edema, diffuse laryngeal edema, posterior commissure hypertrophy, granuloma/granulation tissue, and thick endolaryngeal mucus. The RFS was determined by two laryngologists in 40 patients with abnormal distal or proximal pH probe studies. All study patients were prospectively evaluated before treatment and at 2, 4, and 6 months after proton pump inhibitor treatment. There was an improved RFS with antireflux therapy and interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility between the two observers.

The scoring system by Vavricka et al12 evaluated 10 supraglottic regions: posterior pharyngeal wall, interarytenoid bar, posterior commissure, posterior cricoid wall, arytenoid complex, true vocal cords, false vocal folds, anterior commissure, epiglottis, and aryepiglottic fold. In this study there was a poor correlation between abnormalities of the laryngopharyngeal area and documented esophageal reflux defined by esophageal endoscopic abnormalities. The authors questioned the diagnostic specificity of abnormal laryngopharyngeal findings attributed to reflux.

We previously noted in 58 patients with refractory asthma that 44 (78%) had an SGI ≥ 10.6 Forty-three of these had GER testing, and 34 had documented GER. Fourteen patients had an SGI < 10, with nine having GER testing, eight of whom had negative results. The SGI was significantly higher in the patients with GER (15.8 [SD, 3.6]) than those without GER (8.9 [SD, 5.5], P < .0001). Additionally, two patients with an SGI > 10 and negative GER studies were placed in the nonspecific phenotype, as they did not meet the study criteria (including GI reflux studies) for any phenotypes. Several months post study, they returned still not improved. Both now had a positive GER study. Directed reflux treatment improved their asthma control and lung function. Because of the strong correlation between the SGI and GER, we believed this would be an excellent diagnostic tool to identify patients with LPR contribution to their pulmonary problems while avoiding potential false-negatives or false-positives from GI studies.

Study limitations include the limited number of “naive” SGI pulmonologists (all faculty from National Jewish Health) who represented the learning group. However, they did represent junior and senior pulmonologists as well as academic and recent private practice physicians. Additional studies are needed to evaluate nonpulmonologists with expertise in laryngoscopy (both physicians and other health-care providers) as to the success of this educational program in those populations. It should be noted that the SGI has only been studied in patients with refractory asthma, and its use in diagnosing LPR has not been demonstrated in other conditions. Other limitations are not including additional supraglottic and subglottic areas in the scoring. However, we wanted to produce a relatively simple and functional scoring system.

The purpose of this current study was to demonstrate the teaching technique and reproducibility of the SGI using five SGI scoring-naive physicians who perform bronchoscopy. The teaching technique was prospectively developed but modified between sessions with feedback from the naive readers. Modifications were made mainly to focus discussion on areas of “overreading” and “underreading.” This simple focus change improved understanding of the scoring system. From the initial to final SGI scoring there was marked overall improvement in variability between the naive and control readers and, in particular, the important SGI cut point of 10. The intraobserver consistency was also very tight, as demonstrated by reader E.

The importance of LPR contributing to a multitude of pulmonary conditions is significant. Most previous publications have focused on classic GER, an esophageal disorder, not a pulmonary condition. The criteria used to establish a diagnosis of GER does not include the multiple potential causes for pulmonary complications related to LPR with potential aspiration. One aspiration event can produce lung irritation and subsequent inflammation. Recurrent LPR with aspiration may manifest itself with many different pulmonary problems, such as refractory asthma,6 ground-glass infiltrates,13 interstitial lung disease,14 bronchiectasis,15,16 and aspiration pneumonitis.17

Although it is important to use well-established GI studies to document and elucidate specific pathophysiologic problems, false-positives and false-negatives may occur. Dual-channel pH-impedance probes, Bravo studies, modified and regular barium swallows, and esophageal manometry evaluate potential abnormalities at one point in time. In contrast, careful endoscopy of the supraglottic area and calculating a supraglottic index allows the bronchoscopist to have an anatomic picture of events that have occurred over time, not just a single snapshot or a recording of isolated events.

The challenge that remains is training and educating caregivers to accurately assess the supraglottic area with a tool that is not too cumbersome. In this study it took four separate reading sessions of different still and video recordings of multiple different patients for the naive readers to have consistent and reproducible results compared with the control reader. Although an initial labor-intensive period is needed for any naive reader to become proficient in the SGI scoring system, the effort pays off in better classification and thus treatment of patients with refractory asthma. We now have an extensive online educational teaching program for learning to score the SGI.18

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Martin takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Dr Good: contributed to study design, data collection, analyses, and manuscript writing.

Dr Rollins: contributed to study design, data collection, analyses, and manuscript writing.

Dr. Curran-Everett: contributed to study design, data collection, analyses, and manuscript writing.

Dr Lommatzsch: contributed to design, data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing.

Dr Carolan: contributed to study design, data collection, analyses, and manuscript writing.

Dr Stubenrauch: contributed to study design, data collection, analyses, and manuscript writing.

Dr Martin: contributed to study design, data collection, analyses, and manuscript writing.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following conflicts of interest: Dr Good has performed speaking activities for Merck & Co, Inc and Genentech, Inc and received a research grant from MedImmune, LLC. Dr Lommatzsch has performed speaking activities for Novartis Corp. Dr Carolan has performed speaking activities for Novartis Corp. Dr Martin has done consultancy work and/or received travel support and/or honoraria for attendance at advisory boards for Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries, Ltd, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, LLC, and Merck & Co, Inc; received research grants from MedImmune and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and received royalties from UpToDate, Inc. Drs Rollins, Curran-Everett, and Stubenrauch have reported that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Other contributions: The authors thank Elizabeth Kellermeyer, BA, and Sarah Murrell, BS, for manuscript transcription and editing.

Abbreviations

- GER

gastroesophageal reflux

- LPR

laryngopharyngeal reflux

- RFS

reflux finding score

- SGI

supraglottic index

Footnotes

Funding/Support: The authors have reported to CHEST that no funding was received for this study.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society Proceedings of the ATS workshop on refractory asthma: current understanding, recommendations, and unanswered questions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(6):2341-2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Gwynn C, Redd SC. Surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980-1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(1):1-13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Morbidity and Mortality: 2002 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute) Third Expert Panel on the Management of Asthma. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US) Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; 2007. NIH publication 07-4051 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. ; GOAL Investigators Group Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):836-844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Good JT, Jr, Kolakowski CA, Groshong SD, Murphy JR, Martin RJ. Refractory asthma: importance of bronchoscopy to identify phenotypes and direct therapy. Chest. 2012;141(3):599-606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curran-Everett D. Explorations in statistics: regression. Adv Physiol Educ. 2011;35(4):347-352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ludbrook J. Linear regression analysis for comparing two measurers or methods of measurement: but which regression? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37(7):692-699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Team RDCR. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altman D. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1991:404 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS). Laryngoscope. 2001;111(8):1313-1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vavricka SR, Storck CA, Wildi SM, et al. Limited diagnostic value of laryngopharyngeal lesions in patients with gastroesophageal reflux during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(4):716-722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naidich DP, Zerhouni EA, Hutchins GM, Genieser NB, McCauley DI, Siegelman SS. Computed tomography of the pulmonary parenchyma. Part 1: distal air-space disease. J Thorac Imaging. 1985;1(1):39-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobin RW, Pope CE, II, Pellegrini CA, Emond MJ, Sillery J, Raghu G. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(6):1804-1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moulton BC, Barker AF. Pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. Clin Chest Med. 2012;33(2):211-217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilowite J, Spiegler P, Chawla S. Bronchiectasis: new findings in the pathogenesis and treatment of this disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21(2):163-167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Field SK, Field TS, Cowie RL. Extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2001;47(3):137-150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Supraglottic Index Learning Program National Jewish Health website. http://www.njhealth.org/SGI. Accessed September 20, 2013