Abstract

Arthroscopic surgery has been widely used for treatment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) internal derangements and diseases for the last 40 years. Although 626 articles have been hit by Pubmed search in terms of “TMJ arthroscopic surgery”, this review article is described based on distinguished publishing works and on my experiences with TMJ arthroscopic surgery and related research with an aim to analyse the rationale of arthroscopic surgeries of the temporomandibular joint.

With arthrocentesis emerging as an alternative, less invasive, treatment for internal derangement with closed lock, the primary indication of arthroscopic surgery seems to be somewhat limited. However, the value of endoscopic inspection and surgery has its position for both patient and physician with its long-term reliable results.

Keywords: Temporomandibular joint, Arthroscopy, Arthroscopic surgery

1. Brief history of TMJ arthroscopy

Dr. Ohnishi firstly performed TMJ arthroscopy in 1974 and reported its skill in 1975 in the Japanese literature.1–4 In 1980, Murakami started cadaver study in the Department of Anatomy in cooperation with orthopedic surgeons, and clinically applied it to patients with internal derangement and arthrosis.5–7 Also in Sweden, Holmlund and Hellsing had developed their independent and unique investigations regarding TMJ arthroscopy.8,9 McCain presented his research and development of puncture technique, irrigation system and arthroscopic surgery.10,11 Sanders started his therapeutic arthroscopy based on his sufficient open surgery experience together with information of diagnostic arthroscopy in Japan, and published his distinguished work of TMJ arthroscopic lysis and lavage in 1986.12 Dr. Ohnishi had actively equipped his operative arthroscope with laser, suturing, and double-channeled scopes.3,4 By 1980's, arthroscopy of the TMJ had developed as a diagnostic tool and then as the surgical intervention for patients with TMJ diseases, and eventually soon spread all over the world.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, a large number of articles and publications regarding TMJ arthroscopy were published. Arthroscopy related studies such as intra-articular pathology and synovial fluid analysis contributed to the advancement of the biologic basis of TMJ disorders. Milam and Schmitz (1995)13 reviewed the rationale and role of molecular pathological sequences in synovial fluid of diseased TMJ, hypothesized and proposed several pathways. After that, enormous series of investigations regarding the TMJ synovial fluid analysis in relation with arthroscopy were carried out. Those studies14–23 demonstrated that various cytokines, pain mediators, and substances detected were higher in diseased TMJ compared with the control, and closely linked to the pain and/or osteoarthritic changes. The significance and value of the synovial fluid analysis in TMJ are, however, still on the way to work. Israel is one of pioneers of TMJ synovial fluid research and excellent surgeon as well. In 1999, he reviewed and nicely discussed the success of arthroscopic surgery from 11 case studies of 1987–1996, and indicated the TMJ arthroscopy is a valuable minimal invasive surgery in a data of 6071 joints of 3955 patients.24

2. Arthroscopic lysis and lavage for TMJ closed lock

The success of arthroscopic surgery drastically changed the surgical intervention to the TMJ internal derangement and arthrosis.12

This surgical technique consisted of arthroscopic sweep of the adhesions in the upper joint compartment by blunt trocar and lavage of the joint space (Figs. 1–4). The great advantage was that the procedure could be done by a single puncture technique in about half an hour.

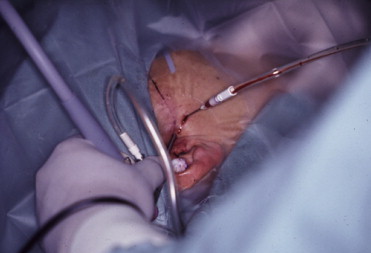

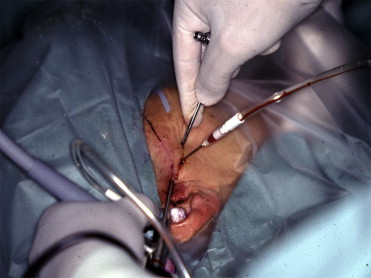

Fig. 1.

Setting up of the diagnostic arthroscopy (not yet connecting inflow).

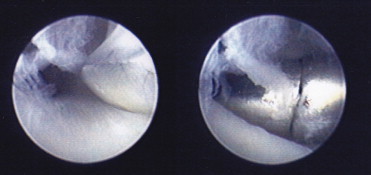

Fig. 2.

Inspection is moving to the anterior recess.

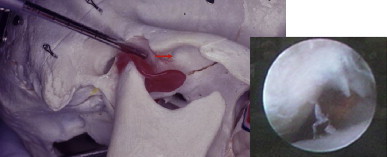

Fig. 3.

Tip of the trocar should be placed anterolateral aspect of the recess (arthroscopic view shows anterior slope of the eminence with fibrillation and disc below). Note: for the procedure explanation, part of Figs. 3, 4 and 11 are horizontally changing the view of the original pictures.

Fig. 4.

Blunt trocar is placed anterior synovial recess. Arrows indicate the area for lysis and lateral release. Adhesions are commonly detected in this compartment (arthroscopic typical view of fibrous adhesions).

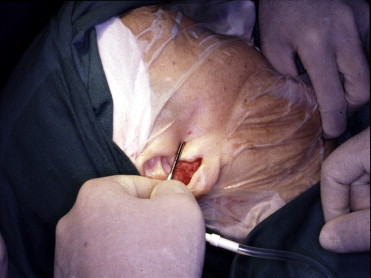

Principal surgeon should have the opportunity of training, but the learning curve is high under the sufficient experience of arthrocentesis and open surgery. Assistant surgeon's manipulation of the mandible is extremely important for both obtaining successful joint mobilization and maintaining the safety procedure (Fig. 5). The staff in the operation theater should check the endoscopic monitor and surgical field (Fig. 6) that contribute towards the quality control of the surgery. General anesthesia is advisable, whereas the procedure has been possibly done in the ambulatory operation theater and/or in the office. One technical advise is that when placing the out-flow needle is difficult, the surgeon should inflame the joint space with injection, puncture the scope and inspect first, secondly insert the needle for the flashing out. Another point is the tip of scope must exactly be placed in the lateral aspect of the anterior recess before the lysis of joint space, (Figs. 3 and 4). Because adhesions commonly occur there, the lateral release can be precisely done. The skillfull assistant surgeon can eventually recognize the mobilization of jaw.

Fig. 5.

Arthroscopic sweep, lysis of adhesions by blunt tip with outer sheath. Note the opposite assistant surgeon hold the patient jaw for manipulation.

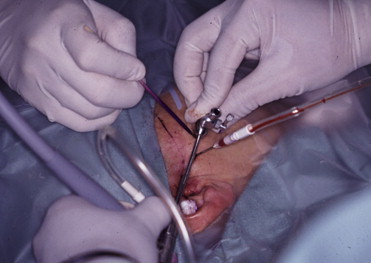

Fig. 6.

Operative setting up and two assistant surgeons (for manipulating, and another for joint lavage with in- and out-flow).

The postoperative study concerning the disc position and clinical interpretation showed that there was excellent outcome regardless of anatomical disc reduction.25,26 This suggested that, in contradiction to the previous concept of the surgical disc repositioning procedure, the simple arthroscopic lysis enabled getting joint mobilization and lavage of diseased joint fluid, making significant pain reduction.

3. Operative arthroscopy by double puncture

McCain has actively contributed in the development of both hard and soft (devices and skills) of the operative TMJ arthroscopy (1996).27 His triangulation technique for the second puncture enabled the safety arthroscopic surgical access to the upper joint compartment (Figs. 7–12). The procedure of anterior release and posterior cauterization was introduced for the reliable lysis of adhesions and disc mobilization under arthroscopic direct vision (Fig. 6). He organized International TMJ Arthroscopy Faculties for the Annual New York Symposium. Regarding the operative device including several equipments such as arthroscopic hand instruments, electric cautery, Nd-YAG (Ohnishi, 1991)28 and Holmium laser (Koslin, 1993),29 and the motorized shaver (Quinn, 1994)30 were developed, presented, discussed in the meeting, and applied to clinical use. His basic concept was that exactly the same surgical manner was to be done arthroscopically for the intra-articular pathology and diseases. Latest surgical modality, the high-frequency wave system, named Coblation (González-García, 2009, Chen, 2010),31,32 is very useful device for both tissue coagulation, debridement and cutting (Fig. 13).

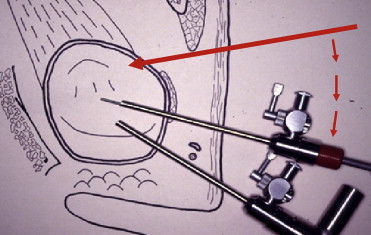

Fig. 7.

Measure and marking for the second puncture.

Fig. 8.

Second puncture.

Fig. 9.

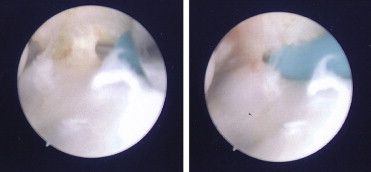

Arthroscopic view of insertion of tip of trocar to the anterior recess (left to right picture in consequence).

Fig. 10.

Completion of second puncture is also confirmed by out-flow from the outer cannula.

Fig. 11.

Schematic view shows second puncture and outer sheath moving with probe.

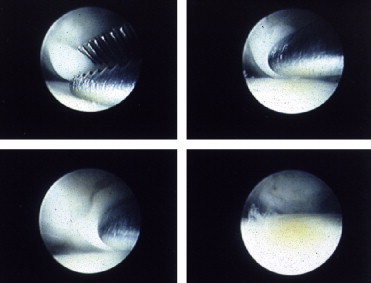

Fig. 12.

Alligator forceps are inserting and removing the debris.

Fig. 13.

Use of the radio frequency system (Coblation) for cutting tight adhesions and debridement.

On the contrary, the arthroscopic disc repositioning surgery by suturing technique is still controversial. Although various arthroscopic disc repositioning/suturing techniques were reported in the late 1990s,28,33–35 the success rate was comparable to arthroscopic lysis and lavage, and the documentation by postoperative imaging was insufficient. Complicated arthroscopic disc repositioning and suturing might not be considered as the routine procedure. The skillful arthroscopic surgeon may possibly carry out the procedure when necessary, but the procedure is very complicated and challenging for the practical surgeon. Meanwhile, the open disk repositioning surgery was later modified after Wolford (Mehra and Wolford, 2001)36 by using Mitek® anchor. It has been positively paid keen attention for the management of patient with idiopathic/progressive condylar resorption (ICR). Yang (2012)37 applied a new disc repositioning and suturing arthroscopic technique for a large number of patients with internal derangement and/or with ICR in adolescent. He beautifully showed the regeneration of absorbed condylar head by MRI follow-up study, and suggested the evolution of surgical treatment modality for ICR patients.

4. Arthroscopic lysis and lavage vs operative arthroscopy

Based on studies undertaken between lysis and lavage versus operative arthroscopy, the comparison of arthroscopic outcomes, showed no apparent difference in the postoperative clinical sign and symptoms. White (2001)38 questioned why should the patients be subjected to the added expense and potentially more morbid procedure of advanced surgical instruction? On the contrary, Indersano (2001)39 claimed that double puncture operative arthroscopy was the best method for addressing heterogeneous aspects of the problem for patients with internal derangement involving inflammatory changes in the joint and mechanical dysfunction. The joint can be treated by multiple ways including debridement of pain-producing tissues, reestablishing functional movements and decreasing the acute inflammatory response, and changing the dynamics to prevent further inflammation.

The long-term outcome studies including both lysis and lavage, and operative arthroscopy indicated that an arthroscopic surgery was a highly predictable and reliable procedure.40–42 The long-term outcomes by sole arthroscopic lysis and lavage were also reported as excellent.43,44

Arthroscopic outcome studies applied to the different Wilkes stages of internal derangement (Wilkes, 1989)45 disclosed generally acceptable results46,47 but the procedure of lysis and lavage was chosen for stage 3 and 4, and operative arthroscopy for late stage 4 and 5 diseases. In the past, Murakami also believed that the arthroscopic lysis and lavage was good and indicated in stage 3–4, and advanced arthroscopic was favorably indicated in the stage 5 of TMJ internal derangement and arthrosis. Whereas, the long-term follow-up study of the arthroscopic lysis and lavage for different stage 3–5 disclosed that there was comparable good outcome.48,49 Somehow, Muñoz-Guerra et al (2013)50 published the long-term results after operative arthroscopy for TMJ disc perforation, and the results indicated that the procedure was favorable in cases with small perforations, but not for medium/large disc perforations. Although, operative arthroscopy is a reliable endoscopic surgery for the advanced intra-articular pathology, it has a limitation. These studies suggest that the arthroscopic lysis and lavage is a favorable initial procedure irrespective of Wilkes staging.

The author started the arthroscopic procedure from diagnostic arthroscopy by single puncture, and lysis and lavage was done when the pathology did not look complicated. If a sufficient movement of jaw was not achieved, under the double puncture the operative arthroscopy was to be performed by probe, instruments and/or Coblation as well as Holmium laser when available. Thus the arthroscopic lysis and lavage, or the operative arthroscopy, is not the matter of debate, but the choice and surgical strategy. According to the intra-articular pathology, and surgeon's skill, a different decision could be made. Indeed, if it is not a matter of arthroscopic skill, an open arthrotomy is always another surgical option.

5. Arthroscopy and arthrocentesis

Obviously, arthrocentesis (Nitzan)51 is much easier and beneficial, and less invasive for the patients with TMJ closed lock. The surgeon can simply perform the procedure in the office under local anesthesia with or without sedation. The learning curve is higher than the arthroscopy, and the previous comparative studies have shown a similar efficacy for reduction of pain and disability.52,53 Current comparative studies of arthroscopy vs arthrocentesis54,55 disclosed that both surgical interventions were effective for pain reduction and jaw functional recovery. While, they stated that the arthroscopic surgery was more useful as a diagnostic and therapeutic adjunct and/or showed better results in terms of jaw range of motion.

Sanders (2004)56 related arthroscopic lysis and lavage and arthrocentesis as “1st cousins”, stated both to have proven effectiveness, and believed that arthrocentesis would not have developed without arthroscopy. Thus, he suggested that there was no controversy on arthroscopy and arthrocentesis. Furthermore, he described that by the level of involvement in the management of TMD, oral and maxillofacial surgeon should have the role, i.e., in minimal; for the diagnosis and referral, moderate; nonsurgical treatment and arthrocentesis, active; arthroscopy, condylectomy and/or arthrotomy, and subspecialty; revision, reconstruction and/or replacement surgery.

So far, the first minimal invasive surgical intervention to TMJ is a single arthrocentesis (called pumping)57 followed by arthrocentesis with lavage in the office. Arthrocentesis under general anesthesia is not my preference, because essentially the arthrocentesis is the blind procedure, and there will be less diagnostic information. When the pumping and/or arthrocentesis is refractory for the patient, the arthroscopic surgery is indicated. In the last decade, the diagnostic arthroscopy of fine diameter with simultaneous arthrocentesis has been another option as a valuable diagnostic and therapeutic modality.58–61

6. Arthroscopy vs open arthrotomy

Meta-analysis by Reston and Turkelson62 showed that there was no statistically significant difference among the effects of any treatments including arthrocentesis, arthroscopy and open disk repositioning/repair. Other retrospective studies of outcome and morbidity of arthroscopic surgery vs open arthrotomy disclosed that the success rate was in comparable.63,64 Holmlund et al (2001)65 conducted a randomized controlled trial to compare discectomy and arthroscopic lysis and lavage for the treatment of TMJ chronic closed lock. Although they found discectomy to reduce pain somewhat more effectively than arthroscopy, both showed similarly good outcomes at 1-year follow-up.

The author believed arthroscopic lysis and lavage was indicated in stage 3–4 of TMJ internal derangement and arthrosis, and open arthrotomy in some stage 5 diseases. But, when postoperative jaw function, especially range of jaw motion was compared after arthroscopic surgery with open arthrotomy, results were more favorable in the arthroscopy group. Discectomy frequently manifested in the deformation of the condyle later. On the other hand, minimum osseous changes were documented after arthroscopic surgery. This suggested that arthroscopic surgery could be a favorable procedure even for advanced staged disease. However, it should be kept in mind that in a complicated advanced intra-articular pathology such as severe fibrosis and adhesions, the surgeon should not hesitate to use an open procedure.

In the UK survey (Thomas et al, 2011),66 41 of 215 (60% of all consultants) surgeons responded that they currently used arthroscopy, and 33 of those (81%) have more than 5 years' experience. During the past year, a total of 8 consultants nationally have done 20 arthroscopies or more. Number of 33 procedures (81%) was done for both diagnosis and treatment. Lack of perceived need of patients and lack of interest in this specialty were the main reasons given for not doing arthroscopy, lack of training being a key secondary reason. They concluded that the results seemed to support the opinion that arthroscopy of the TMJ is under-used, and consideration should be given to ensure that the trainees are instructed in its use, which is important in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the TMJ.

7. Nonsurgical and surgical management for TMD patient

Any surgical intervention would be a part of total management sequences. Although appropriate nonsurgical treatment along with natural course of TMD should be proceeded, there is no obvious consensus regarding the time, duration, and sort of modality.

RCT study of four therapeutic strategies for TMJ closed lock has been well conducted (Schiffman et al, 2007).67 For 106 patients of disc displacement without reduction with limited mouth opening, a single-blind trial was carried out. Group of patients were randomized among four groups, 1) Medical management (included education to the participants, self-help program, and six day regimen of oral methylprednisolone followed by NSAIDs for 3–6 weeks, etc). 2) Rehabilitation (physical therapy or splint fabrication or cognitive-behavioral therapy with medical management, respectively), and 3) Arthroscopic surgery or 4) Arthroplasty with postoperative rehabilitation. Evaluations were done at baseline and up to 60 months for jaw function by CMI (Craniomandibular Index) and TMJ pain by SSI (Symptom Severity Index) respectively. The study disclosed no between-group difference at any follow-up, and significant within-group improvement (p < 0.0001) for all groups. The authors suggested that primary treatment for individuals with TMJ closed lock should consist of medical management or rehabilitation, and concluded that the use of this approach would avoid unnecessary surgical procedures. Whereas, of 29 medical management participants, 45% received a second modality after 3 months for persistent pain and reduced range of motion, thus 12 received rehabilitation after 3 months and one received arthroscopy after 12 months. Regarding participants requiring prescription of analgesics more than once in a week, at 3 months, was significantly higher in medical management group (61%) than rehabilitation, arthroscopy and arthrotomy groups. Participants requiring muscle relaxants were also more (29%) in medical management group. One of the rehabilitation participant received arthroplasty after 6 months. While 2 arthroscopy and one arthroplasty participants received repeat surgeries, one arthroplasty participant experienced nerve injury that resolved completely. It should be notable that open arthroplasty procedure significantly reduced pain level at postoperative 3–18 months.

The study not only showed effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment, but also compared arthroscopy and surgical arthroplasty. The study disclosed that the initial surgical intervention significantly reduced pain, and suggested it might eventually shorten the period of treatment. These suggested that early (less) surgical intervention may avoid unnecessary nonsurgical treatment and its cost.

In this regard, Israel et al (2010)68 reported that arthroscopic lysis and lavage of the TMJ demonstrated better surgical outcomes for the early intervention group than the late. Patients with a shorter duration of symptoms benefited more than those with a longer duration. Slater (2012)69 presented the paper of RCT study regarding the efficacy of early intervention of arthrocentesis to TMJ osteoarthritis. Interestingly, he found a significant reduction of pain after arthrocentesis compared with the conventional conservative treatment group. Treatment time period was shortened as well, and the total cost of patient care was lower to the group of conservative treatment.

The open surgery is an irreversible and invasive surgical procedure, arthroscopic surgery is less invasive and repeatable surgical modality, while arthrocentesis is minimally invasive procedure. These procedures are likely to eliminate pain/disability sooner, and to reduce treatment period as well as the total cost of care when indicated appropriately. Early minimum surgical intervention may also avoid unnecessary invasive and irreversible surgery.

8. EBM of surgical interventions to TMJD

Regarding the surgical interventions including arthrocentesis, arthroscopic surgery and open surgery, twenty-two studies, comprising 30 patient groups and sample sizes of 11–237 patients, that met the inclusion criteria for their analysis, were interpreted Ng CH et al (2005).70 In patients with disc displacement without reduction, the proportion of patients who improved after arthroscopy or arthrocentesis was significantly greater than zero at all three levels of estimated control improvement. Disc repair effect size was not significant at 75% rate. They concluded that surgical treatments appeared to have some efficacy for people who had TMD that did not respond to nonsurgical therapies. Regarding arthrocentesis (Currie, 2009),71 just two trials was evaluated, and there was no statistically significant difference between arthrocentesis and arthroscopy in terms of pain. A statistically significant difference was found in favor of arthroscopy in maximum incisal opening. Regarding arthroscopy (Currie, 2011),72 seven RCT were interpreted, and both arthroscopy and nonsurgical treatment reduced pain after six months. When compared with arthroscopy, the open surgery was more effective at reducing pain after 12 months. Nevertheless, there were no differences in mandibular functionality or in other outcomes in clinical evaluations. Arthroscopy led to greater improvement in maximum interincisal opening after 12 months than arthrocentesis; however, there was no difference in pain.

In general, only very weak evidence was found on some surgical intervention to TMJ internal derangement.

9. Current concept of arthroscopy for the management of TMJD patient

In the last three decades, arthroscopy has shown best efficiency for functional recovery in terms of jaw range of motion for patients with painful limited jaw opening (closed lock) among the nonsurgical treatment, arthrocentesis, and open arthrotomy. On the other aspect, arthrocentesis is the least invasive surgical intervention for patient. Israel (1999)24 claims that articular cartilage and the synovial membrane are intra-articular connective tissues having specific functions necessary for the maintenance of a healthy joint. Successful management of patients with TMJ pathology requires greater emphasis on the reduction of joint loading, inflammation, and pain, thus enables maximizing joint mobility, and less emphasis on the restoration of anatomic relationships. He states that basic principles of TMJ arthroscopic surgery require preservation of 1) synovial membrane for providing joint lubrication, 2) articular cartilage to maintain the properties of resiliency and compressibility, 3) the disc for giving a biomechanical advantage and hydrostatic/weeping lubrication. Also he emphasizes on 4) intra-articular biopsy for histologic review, and 5) removal of adhesions, impediments to joint motion. In 1995, Trumpy and Lyberg73 stated the importance of functioning disc in the TMJ. They observed that development of osteoarthrosis was significant higher in the group with discectomy with or without disc substitute than the discoplasty group.

Based on these experiences and literature, the initial surgical intervention should apparently be starting from the single arthrocentesis and/or with lavage, and then arthroscopic surgery. The alternative and irreversible surgical intervention is the open arthroplasty or discectomy. However, the failure of certain surgical treatment does not automatically mean the next surgical option. It is advisable to go back to the initial diagnosis, have team discussion and critical conference is mandatory.

Since 1975, arthroscopy of TMJ has been applied to clinical use primarily as a diagnostic procedure followed by minimally invasive surgical intervention. Basic investigations of TMJ arthroscopy and related surgery significantly inspire the progression of the diagnostic science through the findings of intra-articular pathology and by the cumulated data of synovial fluid analysis. Both arthroscopic surgery and arthrocentesis with lavage are now established as a minimum invasive intervention for TMJ diseases. Based on the evidence based management for TMD patient, further sound science clinical research would be awaited.

Conflicts of interest

The author has none to declare.

Acknowledgment

Part of figures and photographs were modified and used from my Japanese publication in the Hand Manual of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery '13. Quintessence Japan. Tokyo. 2013. p.107–113.

References

- 1.Ohnishi M. Arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint. J Jpn Stomatol Soc. 1975;42:207–213. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohnishi M. Clinical application of arthroscopy in the temporomandibular joint diseases. Bull Tokyo Med Dent Univ. 1980;27(3):141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohnishi M. Arthroscopic surgery for hypermobility and recurrent mandibular dislocation. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1989;1:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohnishi M. Newly designed needle scope system for arthroscopic surgery by double-channel sheath method. J Jpn Soc TMJ. 1989;1(1):209–216. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murakami K., Ito K. In: Arthroscopy of Small Joints. Arthroscopy of the Temporomandibular Joint. Watanabe M., editor. Igaku-Shoin; Tokyo, New York: 1985. pp. 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murakami K., Ono T. Temporomandibular joint arthroscopy by inferolateral approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15:410–417. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(86)80029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murakami K., Matsuki M., Iizuka T. Diagnostic arthroscopy of the TMJ: differential diagnoses in patients with limited jaw opening. J Craniomandib Pract. 1986;4:118–123. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1986.11678136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellsing G., Holmlund A., Nordenram A. Arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint. Examination of 2 patients with suspected disk derangement. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13(1):69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmlund A., Hellsing G. Arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint. An autopsy study. Int J Oral Surg. 1985;14(2):169–175. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(85)80089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCain J.P. Arthroscopy of the human temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(8):648–655. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCain J.P., de la Rua H. Arthroscopic observation and treatment of synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint. Report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;18(4):233–236. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(89)80060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders B. Arthroscopic surgery of the temporomandibular joint: treatment of internal derangement with persistent closed lock. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1986;62:361–372. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milam S.B., Schmitz J.P. Molecular biology of degenerative temporomandibular joint disease: proposed mechanism of disease. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:1448–1454. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90675-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israel H., Saed-Nejad F., Ratcliffe A. Early diagnosis of osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint: correlation between arthroscopic and keratan sulfate levels in synovial fluid. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:708–711. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinn J.H., Bazan N.G. Identification of prostaglandin E2 and leukotriene B4 in the synovial fluid of painful, dysfunctional temporomandibular joints. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(9):968–971. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90011-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafer D.M., Assael L., White L.B. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha as a biochemical marker of pain and outcome in temporomandibular joints with internal derangements. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:786–791. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandler N.A., Buckley M.J., Cillo J.E. Correlation of inflammatory cytokines with arthroscopic findings in patients with temporomandibular joint internal derangements. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:534–543. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israel H.A., Diamond B.E., Saed-Nejad F. Correlation between arthroscopic diagnosis of osteoarthritis and synovitis of the human temporomandibular joint and keratan sulfate levels in the synovial fluid. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:210–217. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murakami K., Shibata T., Kubota E. Intra-articular levels of prostaglandin E2, hyaluronic acid, and chondroitin-4 and -6 sulfates in the temporomandibular joint synovial fluid of patients with internal derangement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90869-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi T., Kondoh T., Ohtani M. Association between arthroscopic diagnosis of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis and synovial fluid nitric oxide levels. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999 Aug;88:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki T., Segami N., Nishimura M. Bradykinin expression in synovial tissues and synovial fluids obtained from patients with internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Cranio. 2003;21(4):265–270. doi: 10.1080/08869634.2003.11746261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato J., Segami N., Suzuki T. The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in synovial tissues in patients with internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93(3):251–256. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.122161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumagai K., Hamada Y., Holmlund A.B. The levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in the synovial fluid correlated with the severity of arthroscopically observed synovitis and clinical outcome after temporomandibular joint irrigation in patients with chronic closed lock. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Israel H.A. The use of arthroscopic surgery for treatment of temporomandibular joint disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:579–589. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(99)90079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moses J.J., Sartoris D., Glass R. The effect of arthroscopic surgical lysis and lavage of the superior joint space on TMJ disc position and mobility. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:674–678. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(89)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montgomery M.T., Van Sickels J.E., Harms S.E. Arthroscopic TMJ surgery: effects on signs, symptoms, and disc position. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:1263–1271. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCain J.P., editor. Principles and Practice of Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy. Mosby; St. Louis: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohnishi M. Arthroscopic laser surgery and suturing for temporomandibular joint disorders: technique and clinical results. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(2):212–220. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90110-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koslin M.G., Martin J.C. The use of the holmium laser for temporomandibular joint arthroscopic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51(2):122–123. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinn J.H. Arthroscopic management of temporomandibular joint disc perforations and associated advanced chondromalacia by discoplasty and abrasion arthroplasty: preliminary results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52(8):800–806. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.González-García R. Arthroscopic myotomy of the lateral pterygoid muscle with coblation for the treatment of temporomandibular joint anterior disc displacement without reduction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(12):2699–2701. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen M.J., Yang C., Zhang S.Y. Use of coblation in arthroscopic surgery of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010 Sep;68(9):2085–2091. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Israel H.A. Technique for placement of a discal traction suture during temporomandibular joint arthroscopy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:311–313. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90240-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarro A.W. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior disc displacement: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:353–358. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCain J.P., Podrasky A.E., Zabiegalski N.A.J. Arthroscopic disc repositioning and suturing: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:568–579. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehra P., Wolford L.M. The Mitek mini anchor for TMJ disc repositioning: surgical technique and results. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30(6):497–503. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang C., Cai X.Y., Chen M.J. New arthroscopic disc repositioning and suturing technique for treating an anteriorly displaced disc of the temporomandibular joint: part I – technique introduction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(9):1058–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White D.R. Arthroscopic lysis and lavage as the preferred treatment for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:313–316. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.21002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Indersano A.T. Surgical arthroscopy as the preferred treatment for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:308–312. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Indersano T. Arthroscopic surgery of the temporomandibular joint: report of 64 patients with long-term follow-up. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:439–441. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCain J.P., Sanders B., Koslin M.G. Temporomandibular joint arthroscopy: a 6-year multicenter retrospective study of 4,831 joints. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:926–930. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murakami K., Segami N., Okamoto M. Outcome of arthroscopic surgery for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: long-term results covering 10 years. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28:264–271. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders B., Buoncristiani R. A 5-year experience with arthroscopic lysis and lavage for the treatment of painful temporomandibular joint hypomobility. In: Clark G., Sanders B., Bertolami C., editors. Modern Diagnostic and Surgical Arthroscopy of the Temporomandibular Joint. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1993. pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorel B., Piecuch J.F. Long-term evaluation following temporomandibular joint arthroscopy with lysis and lavage. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;29:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkes C.H. Internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint. Pathological variations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989 Apr;115(4):469–477. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1989.01860280067019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brronstein S.L., Merill R.G. Clinical staging for TMJ internal derangement: application to arthroscopy. J Craniomandib Disord. 1995;6:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murakami K., Tsuboi Y., Yokoe Y. Operative outcome of TMJ arthroscopic surgery correlate to stages of internal derangements – five-years follow-up study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;36:30–34. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smolka W., Iizuka T. Arthroscopic lysis and lavage in different stages of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: correlation of preoperative staging to arthroscopic findings and treatment outcome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.González-García R., Rodríguez-Campo F.J. Arthroscopic lysis and lavage versus operative arthroscopy in the outcome of temporomandibular joint internal derangement: a comparative study based on Wilkes stages. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2513–2524. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muñoz-Guerra M.F., Rodríguez-Campo F.J., Escorial Hernández V. Temporomandibular joint disc perforation: long-term results after operative arthroscopy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(4):667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nitzan D.W., Dolwick M.F., Martinez G.A. Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis: a simplified treatment for severe, limited mouth opening. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49(11):1163–1167. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murakami K., Hosaka H., Moriya Y. Short-term treatment outcome study for the management of temporomandibular joint closed lock: a comparison of arthrocentesis to nonsurgical therapy and arthroscopic lysis and lavage. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1995;80:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friedrich K.I., Wise J.M., Zeitler D.L. Prospective comparison of arthroscopy and arthrocentesis for temporomandibular joint disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:816–820. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goudot P., Jaquinet A.R., Hugonnet S. Improvement of pain and function after arthroscopy and arthrocentesis of the temporomandibular joint: a comparative study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28:39–43. doi: 10.1054/jcms.1999.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed N., Sidebottom A., O'Connor M. Prospective outcome assessment of the therapeutic benefits of arthroscopy and arthrocentesis of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;28:745–748. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanders B. The history and evolution of TMJ surgery. Presented at UCLA International Symposium. Maui, Hawai; Jan 2004.

- 57.Murakami K., Matsuki M., Iizuka T. Recapturing the persistent anteriorly displaced disk by mandibular manipulation after pumping and hydraulic pressure to the upper joint cavity of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomandib Pract. 1987;5:17–24. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1987.11678169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kondoh T., Dolwick M.F., Hamada Y. Visually guided irrigation for patients with symptomatic internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: a preliminary report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95(5):544–551. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hamada Y., Kondoh T., Holmlund A.B. Visually guided temporomandibular joint irrigation in patients with chronic closed lock: clinical outcome and its relationship to intra-articular morphologic changes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95(5):552–558. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yura S., Totsuka Y., Yoshikawa T. Can arthrocentesis release intracapsular adhesions? Arthroscopic findings before and after irrigation under sufficient hydraulic pressure. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(11):1253–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ogawa J., Kawakami T., Fujita H. Relationship between arthroscopic findings in the superior articular cavity and the effect of arthrocentesis in cases with internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Jpn Soc TMJ. 2005;17:1–6. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reston J.T., Turkelson C.M. Meta-analysis of surgical treatments for temporomandibular articular disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(1):3–10. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zeitler D., Porter B. A retrospective study comparing arthroscopic surgery with arthrotomy and disc repositioning. In: Clark G.T., Sanders B., Bertolami C.N., editors. Advances in Diagnostic and Surgical Arthroscopy of the Temporomandibular Joint. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1993. p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Undt G., Murakami K., Rasse M. Open versus arthroscopic surgery for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: a retrospective study comparing two centres' results using the Jaw Pain and Function Questionnaire. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Holmlund A.B., Axelsson S., Gynther G.W. A comparison of discectomy and arthroscopic lysis and lavage for the treatment of chronic closed lock of the temporomandibular joint: a randomized outcome study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:972–977. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.25818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomas S.M., Matthews N.S. Current status of temporomandibular joint arthroscopy in the United Kingdom. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(7):642–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schiffman E.L., Look J.O., Hodges J.S. Randomized effectiveness study of four therapeutic strategies for TMJ closed lock. J Dent Res. 2007;86(1):58–63. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Israel H.A., Behrman D.A., Friedman J.M. Rationale for early versus late intervention with arthroscopy for treatment of inflammatory/degenerative temporomandibular joint disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(11):2661–2667. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Slater H. International Conference on TMJ Biology, Diagnosis and Surgical Management. October 4-5th, 2012. The effectiveness of TMJ minimally invasive treatment. Groningen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ng C.H., Lai J.B., Victor F. Temporomandibular articular disorders can be alleviated with surgery. Evid Based Dent. 2005;6:48–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Currie R. Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis and lavage. Evid Based Dent. 2009;10:110. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Currie R. Arthroscopy for treating temporomandibular joint disorders. Evid Based Dent. 2011;12:90–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trumpy I.G., Lyberg T. Surgical treatment of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: long-term evaluation of three techniques. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53(7):740–746. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]