Transition from paediatric to adult health care services is fraught with challenges in multiple domains (1) including future health care use, educational and vocational trajectories, family and social life, self-fulfillment and quality of life. Significant gaps in the transition process exist (2–4) and involve both paediatric and adult health care systems. Important challenges include the lack of preparation for transition and transfer (5); adult health care providers’ lack of experience, training and expertise in traditionally paediatric diseases and conditions; loss of a longstanding, trusting relationship with the paediatrician; and suboptimal development of the adult health care physician-youth relationship and communication (5).

Transition in health care is a process in which adolescents gradually prepare for and shift toward care in the adult system. In contrast, the current (albeit sparse) literature regarding perceptions of care during this period indicates that some individuals believe that they were suddenly removed from paediatric care and thrust into a foreign system for which they had not been adequately prepared (2,4). Transition challenges are likely to be greater among youth with neurodevelopmental disabilities (NDDs) because of the complexity of their health care needs and the stigma associated with physical and intellectual disability that may accompany these disorders (2,4–6). From an ethics perspective, a fundamental component of transition is whether individuals with NDDs feel respected, and how their values and autonomy are integrated, developed and supported within the transition (7). There is a paucity of literature regarding how transition programs respond to the complex needs of youth with NDDs and how they specifically respond to ethics concerns that arise during the provision of health care. Therefore, we convened a national workshop to deliberate some of the key ethics challenges for young adults with NDDs during the transition from paediatric to adult care. Our goals were: to identify and validate important ethics issues that arise during transition for youth with NDDs; to discuss how such ethics issues could be handled or addressed; to consider the barriers in implementing change; and to identify the knowledge needed to support informed practices. Building on the activities of NeuroDevNet, a Canadian Network of Centres of Excellence, we subsequently engaged in a collaborative writing process to consolidate the ideas and opinions expressed during the workshop.

CURRENT PERSPECTIVES ON ETHICS CHALLENGES EMERGING DURING TRANSITION

Modern bioethics, and the subfield of neuroethics, which is related to our topic, can be loosely described as an interdisciplinary field committed to generating in-depth understandings of the context in which ethics questions and dilemmas emerge, and providing responses that respect general ethics principles (eg, autonomy, beneficence, justice). An ethical ‘lens’ on transition focuses on understanding the values and preferences of stakeholders, and brings attention to how general ethics principles are challenged or promoted in transition. Reviewing the small set of literature focusing on ethics issues during transition (2,7) or discussing transition programs in the context of NDDs (2,4–6,8) revealed four ethics considerations, for which questions were developed to guide discussion and formulate reflection (Table 1). Several important barriers for implementing change to transitional care in the Canadian context are identified in Box 1.

TABLE 1.

Ethics considerations for transition of youth with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) based on the literature

| Ethics considerations | Highlights from the literature | Questions to explore |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy in transition programs | Lack of adolescent participation in decision making despite major guidelines recommending the contrary (9). Lack of preparation and information for handling health decisions (5). Adolescents are not considered as future adults (10). | What factors are important in the development of autonomy and decision making in adolescents and young adults? How do (or can) transition programs facilitate the development of autonomy in these specific populations? |

| Youth-provider relationships | Adolescents (and parents) can feel considerable anxiety about the process of transition and can feel neglected or abandoned (4). Trust and confidentiality are expected by adolescents and their caregivers (10). Health care providers can be facilitators or obstacles to building trusting relationships (10). | What are appropriate behaviours (conduct, practices and attitudes) that enhance ethical practice by health care providers in the transition period? Which behaviours convey a sense of respect for the individual and which do not? |

| Ethics development in transition programs | Little evidence exists about how ethics is integrated in current transition programs and how it should be integrated (3), and even less evidence exists about this issue for youth with NDDs. | How are ethics principles incorporated into current transition programs? How are ‘poor’ or ‘successful’ transitions apparent from a family perspective and an ethics standpoint? How can the development of ethics in transition programs be evaluated? |

| Common and unique challenges among NDDs | Scarce evidence exists about tailored transition programs for NDDs (2,4–6,8) and ethics in transition for youth with NDD (2). | What similarities or differences exist in ethics challenges during transition among youth with NDDs such as CP, ASD and FASD? |

ASD Autism spectrum disorders; CP Cerebral palsy; FASD Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

Box 1: Barriers to change in transitional care for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs).

Lack of access to primary care physicians after 16 to18 years of age

Lack of coordination and partnership between adult primary health care and paediatric care

Age as the definitive marker for transfer

Less knowledge or interest regarding NDDs in the adult health care system

Lack of resources for a specific group of individuals (young adults with NDDs) in adult care

Lack of simple, cost-effective, user-friendly tools or approaches for transitional care

General complexity of medical needs of many individuals with NDDs

Termination of some government developmental services and assistance programs at time of transfer

General complexity of the health care and social service systems

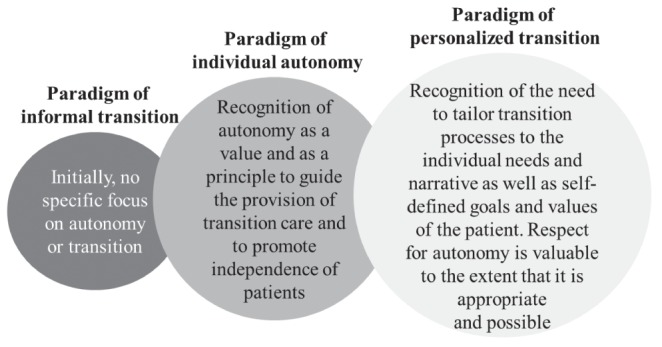

FROM AUTONOMY TO PERSONALIZED TRANSITION

Most transition literature implicitly suggests that the development of autonomy is a fundamental goal of transitional care (7,9–11). In the context of NDDs, this goal is valuable; however, it should be approached with caution (see Table 2 for practical considerations). It is widely recognized by professional societies that children and, especially, adolescents should be engaged in decisions regarding their health in age- and developmentally appropriate manners (12,13). A first issue, however, is that some individuals may endorse other models of autonomy (eg, shared authority such as making decisions with their parents) (11). A second issue is that some individuals with NDDs may value achievements not aligned strictly with the goal of independence. In this case, independence, as a life goal, may be more valued by others (eg, health care providers, family, society) than by youth themselves and their families. More generally, an overly normative (top-down) approach to transition could be deleterious and create arbitrary standards (eg, ‘good’ parenting skills, ‘good’ demonstration of development and attainment of autonomy, ‘responsible adolescent’, ‘good’ and ‘inadequate’ transition) and lead to feelings of inadequacy. Accordingly, personalized transition shaped around the expectations, wishes and narratives of individuals – within their family unit – may be a more comprehensive and holistic goal, and may better reflect the transformative aspects of adolescence. Moreover, to transcend an idealized goal of independence, there must be a call for a change in the evolution of a desired ‘end point’ in ethics in transition programs to a more personalized set of goals (Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Practical considerations for different stakeholders regarding autonomy in transition*

| Practical consideration | Stakeholder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth | Parents | Paediatric physicians | Adult physicians | Other health care providers (ie, nurse, social worker, occupational therapist, physiotherapist) | |

| Transition as a process of autonomy building over time | Understand transition as a normal and ongoing process that begins early in adolescence. Understand which model of autonomy best supports their values and preferences | Encourage progressive autonomy and responsibility of youth. Understand and appreciate the youth’s preferences and life goals | Educate oneself and teach trainees (eg, residents) to identify adolescents’ decision-making capacity and to speak with them about their health and role in their own health care | Educate oneself and teach trainees (eg, residents) to identify young adults’ decision-making capacity and to speak with them about their health and role in their own health care | Build sustainable relationships with youth to facilitate transition. Appreciate the different models of autonomy dependent on individuals’ special health care needs and wishes |

| Preparation for decision making | Participate in in early skill building (eg, time alone with their health care providers, participate in age- and developmentally relevant decisions about their own health management) | Encourage early skill building (eg, expose youth to peer group activities, build their self-esteem, allow youth to communicate about disability and preferences in and out of medical encounters) | Break down stigma regarding NDDs to help promote self-esteem in adolescents. Recognize youths’ decision-making capacity; treat decision making as task specific and encourage decision making where possible | Avoid mischaracterizations or misconceptions about the decision-making capacity of young adults with NDDs | Discuss and support choices of youth during transition (eg, when there is instability at home or school) |

| Relational aspects of autonomy and decision making | Participate in and/or develop peer groups who will also transfer at the same time. Engage in social activities and networks (eg, social media, virtual communities) | Teach youth self-advocacy skills needed during transition (eg, in collaboration with parental peer groups). Understand societal contexts of youth with and without disabilities | Encourage early skill building (eg, balance tension between family involvement and the autonomy and independence of youth; allow the opportunity for assent or dissent). Educate family and youth about the importance of autonomy in promoting the choices and decision making of youth. Encourage youth to seek care throughout the life course by (adult) primary care physicians | Encourage continued care throughout the life course (for primary care physicians and relevant specialty disciplines). Improve understanding of NDDs and knowledge of individual’s abilities for participating in decision making | Facilitate stronger relationships with the health care team to help increase confidence of youth in health care services. Facilitate communication with schools about the child. Provide information about peer groups, virtual communities, camps, etc. Drive continuity of care across transition, accompanying the individual throughout transition |

We acknowledge that some of the recommendations formulated pertain to more than one group of stakeholders (eg, suggestions for allied health care providers could be relevant to some physicians); however, we tried to identify the stakeholders who would be primarily concerned by these suggestions. Recommendations may be more appropriate for youth where the attainment of a certain level of independence is possible. The focus on stakeholders should not obfuscate the need for structural and/or systemic change. NDD Neurodevelopmental disability

Figure 1).

Evolving paradigms of ethics in transitional care

ACKNOWLEDGING AND UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF TRANSITIONAL CARE AND HEALTH CARE PROVIDER ATTITUDES

Several studies report problematic attitudes and behaviours in the ways health care providers communicate and interact with youth with NDDs (10), and suggest that health care providers, health services and transition programs may respond inadequately to the needs of these individuals (2,4–6,8). Discussions highlighted the constructive role health care providers should play in the transition process and the potential for harm and frustration if this role is not fulfilled. However, the negative consequences of suboptimal transition, although present, are insufficiently researched and discussed in the public domain. The paradigm of harm reduction appears to be inadequate in meeting the goals of transitional care completely; however, elements of this concept address important detriments of ineffective transitional care in terms of cost and wasted opportunities for young individuals with NDDs. Nonetheless, this paradigm overlooks the positive contributions that individuals with disabilities make to society that cannot (and should not) be defined in economic terms (ie, the paradigm reduces the intrinsic value of the individual and, thus, of transition programs, to goals of productivity and economic gain). Moreover, if these youth and their families are not given the support to transition into adulthood, the positive contribution brought by the diversity of individuals with disabilities to society may be lost.

TAILORING ETHICS FOR RESPONSIVE TRANSITION PROGRAMS

Because ethics is often an implicit aspect of transition programs, it is often underdiscussed as such. The development of ethics in transition programs will likely assume different shapes and forms, including a better understanding of the needs, perspectives and expectations of different groups as well as individuals and families (eg, through innovative qualitative research). This may help transition programs become more responsive to the values and preferences of different stakeholders and integrate a personalized approach based on the definitions of ‘good transitions’ by those concerned. At the same time, we can avoid perpetuating a model of transition that narrowly supports a medical model of disability (eg, one that emphasizes the deficits of the individual that need to be remediated before transition can occur). Consideration of the social and contextual aspects that can diminish or compound disability should also be one of the critical targets of transition programs. In this respect, upholding a firm age for transition, a common practice (in contrast to a developmentally appropriate time for transition), introduces significant challenges when independence is potentially forced on youth, when the adult system is unable to cope with unprepared patients and when parents are inappropriately left out of shared decision making. Developing policies regarding the appropriate time for transition is one example in which ethics challenges (taken as a subset of social and contextual aspects of disability) could be diminished and responses to these challenges modulated.

TACKLING UNIQUE CHALLENGES AND SHARING RESOURCES

There is unavoidable tension between what is good for the individual and what is good for the larger population. Transition is a common challenge for all adolescents. However, heterogeneity among NDDs (and their complex progressions compared with other chronic conditions) makes it difficult to establish best practices that are applicable to all. Despite this, it is unrealistic or infeasible to develop specific programs for each condition in health care institutions. Therefore, middle-ground approaches (eg, core transitional care supplemented by tailored modules for different types of disabilities, creating an overall personalized approach) were identified as the most likely to stand the test of reality. A range of approaches and combinations of strategies need to be explored to examine how best to respond to the needs of youth with NDDs. There are evident tensions in achieving balance between approaches that focus on systems as opposed to individuals, or that are generalized as opposed to specialized. There is also related tension in defining transition outcomes based on a business model (ie, cost savings of good transition) as opposed to the individual’s quality of life and welfare (ie, a meaningful transition for the individual). Further research should evaluate these aspects of transition programs with an ethical lens.

CONCLUSION

Health care transition is a crucial process in the lives of youth with NDDs and their parents. There are significant gaps in the provision of structured transition processes for youth with NDDs, and the ethics challenges that may arise during transition are poorly understood. We hope that the present article highlights key reflections that will be useful to both practitioners and scholars (Box 2), and that further practical policy and scientific developments will bridge these gaps.

Box 2: Key messages to optimize responsiveness to ethics considerations in transition programs.

Respect stakeholders and their values and preferences

Recognize knowledge and experiences of youth

Revisit age as a trigger for transfer

Refine communication techniques and develop tools for capturing clinical needs, communication styles and preferences of youth

Recognize a broad range of paradigms of disability reflected in transition models

Identify how general ethics principles are challenged or promoted in transition and by specific approaches to transition

Increase awareness of the richness of the principle of respecting autonomy, beyond an ideal of independence

Connect health care transition with the broader goals and needs of young adults growing up with a disability

Consider the balance between individual-centred goals and family- or society-centred goals in transition

Reflect on broadly defined end goals of transition programs, including the supporting role of primary care providers in bridging gaps

Explore the advocacy role of health care providers in the face of suboptimal transition programs and practices

Acknowledgments

FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Funding for the workshop was provided by the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal, NeuroDevNet Central and its Demonstration Projects (Autism Spectrum Disorder, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Cerebral Palsy), and The Sinneave Family Foundation. Writing of this manuscript was made possible by funding from a New Investigator Award (ER) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Career Award of the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (ER). The authors thank the following workshop participants: James Reynolds (Queen’s University, Kingston); Lucy Lach (McGill University, Montreal); Radha MacCulloch (McGill University, Montreal); and Lynn Dagenais (McGill University, Montreal). The authors also thank John Aspler for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Staa AL, Jedeloo S, van Meeteren J, Latour JM. Crossing the transition chasm: Experiences and recommendations for improving transitional care of young adults, parents and providers. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:821–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larivière-Bastien D, Bell E, Majnemer A, Shevell M, Racine E. Perspectives of young adults with cerebral palsy on transitioning from pediatric to adult healthcare systems. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2013;20:154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant C, Pan J. A comparison of five transition programmes for youth with chronic illness in Canada. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:815–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies H, Rennick J, Majnemer A. Transition from pediatric to adult health care for young adults with neurological disorders: Parental perspectives. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;33:32–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binks JA, Barden WS, Burke TA, Young NL. What do we really know about the transition to adult-centered health care? A focus on cerebral palsy and spina bifida. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1064–73. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConachie H, Hoole S, Le Couteur AS. Improving mental health transitions for young people with autism spectrum disorder. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:764–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman H, Horricks L, Kaufman M. Ethical considerations in transition. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2010;22:453–9. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2010.22.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oskoui M. Growing up with cerebral palsy: Contemporary challenges of healthcare transition. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39:23–5. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100012634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinzon J, Harvey J, Canadian Paediatric Society. Adolescent Health Committee Care of adolescents with chronic conditions. Paediatr Child Health. 2006;11:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larivière-Bastien D, Racine E. Ethics in health care services for young persons with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A focus on cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:1221–9. doi: 10.1177/0883073811402074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Racine E, Lariviere-Bastien D, Bell E, Majnemer A, Shevell M. Respect for autonomy in the healthcare context: Observations from a qualitative study of young adults with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39:873–9. doi: 10.1111/cch.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Medical Association CMA Code of ethics (Updated 2004) 2004 < http://policybase.cma.ca/dbtw-wpd/PolicyPDF/PD04-06.pdf> (Accessed October 23, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatr. 1995;95:314–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]