Abstract

Binge Eating Disorder (BED), a chronic condition characterized by eating disorder psychopathology and physical and social disability, represents a significant public health problem. Guided Self Help (GSH) treatments for BED appear promising and may be more readily disseminable to mental health care providers, accessible to patients, and cost-effective than existing, efficacious BED specialty treatments which are limited in public health utility and impact given their time and expense demands. No existing BED GSH treatment has incorporated affect regulation models of binge eating, which appears warranted given research linking negative affect and binge eating. Integrative Response Therapy (IRT), a new group-based guided self-help treatment, based on the affect regulation model of binge eating, that has shown initial promise in a pilot sample of adults meeting DSM IV criteria for BED, is described. Fifty-four% and 67% of participants were abstinent at post-treatment and three month follow-up respectively. There was a significant reduction in the number of binge days over the previous 28 days from baseline to post-treatment [14.44 (±7.16) to 3.15 (±5.70); t=7.71, p<.001; d=2.2] and from baseline to follow-up [14.44 (±7.16) to 1.50 (±2.88); t=5.64, p<.001; d=1.7]. All subscales from both the Eating Disorder Examination – Questionnaire and Emotional Eating Scale were significantly lower at post-treatment compared to baseline. 100% of IRT participants would recommend the program to a friend or family member in need. IRT’s longer-term efficacy and acceptability are presently being tested in a National Institute of Mental Health funded randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: binge eating disorder, emotion regulation, treatment, guided self-help

Background

Prevalence and consequences of BED

Binge Eating Disorder (BED), a diagnostic research category in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), is a chronic disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating without the requisite compensatory behaviors seen in Bulimia Nervosa. BED impacts approximately 2–5% of the general population (Bruce & Agras, 1992), up to 30% of weight control program participants (Spitzer et al., 1992; Spitzer et al., 1993), and up to 49% of those undergoing bariatric surgery (de Zwaan et al., 2003; Niego, Kofman, Weiss, and Geliebter, 2007). Findings from clinic, community, and population-based studies note that BED is associated with overweight and obesity (Bruce & Agras, 1992; Fairburn, Cooper, Doll, Norman, & O’Conner, 2000; Smith, Marcus, Lewis, Fitzgibbon, & Schreiner, 1998, Spitzer et al., 1992; Striegel-Moore, Wilfley, Pike, Dohm, & Fairburn, 2000) and the prevalence of binge eating increases with the Body Mass Index (Telch, Agras, Rossiter, 1988). Through its association with overweight and obesity, BED includes a greater risk for many serious medical conditions (Pi-Sunyer, 1993; Pi-Sunyer, 1998). In addition, when compared to overweight persons without BED, overweight persons with BED have increased rates of Axis I and Axis II psychopathology(Marcus et al., 1990; Yanovski, 1993; Mitchell & Mussell, 1995) and increased rates of interpersonal and work impairments due to weight and eating concerns (Spitzer et al., 1993).

Existing treatments for Binge Eating Disorder

Existing treatments for BED include pharmacological approaches and psychotherapeutic treatments including Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy for BED (DBT-BED), Behavioral Weight Loss (BWL), and various forms of Guided Self-Help (GSH). While pharmacotherapy and specialty psychotherapeutic treatments (e.g., CBT, IPT, DBT-BED) have demonstrated at least moderate efficacy (Vocks et al., 2010), an impetus remains for the development of new BED treatments and further BED research. First, existing treatments yield a significant number of patients who are still symptomatic at post-treatment and follow-up (Munsch et al., 2007; Wilfley et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 2007; Safer, Robinson, Jo, 2010). Second, specialty treatments are expensive, time-intensive (often administered in 6 months of weekly 1–2 hour therapy sessions), and require expert delivery (e.g., therapists typically hold at least a Masters degree and have received advanced training in eating disorders), and therefore are limited in ease of dissemination and patient access. Next, pharmacological treatments, while appearing superior to placebo, yield approximately 50% symptomatic individuals at post-treatment and data on longer-term abstinence rates post medication cessation are limited (Reas & Grilo, 2008). Last, BWL offers a less-expensive treatment option than specialty treatments, yet BWL may not be effective in the treatment of BED over the long-term (Wilson et al., 2010; Grilo et al., 2011).

BED self-help research has varied in terms of methodological quality (e.g., sample size, pathology assessment), settings, and intervention implementation details (Wilson, 2005). Consequently, strikingly different outcomes have been reported. Nonetheless, Guided Self Help (GSH) is short-term, and generally less expensive and more easily disseminable than the specialty treatments (Vocks et al., 2010). Research indicates that GSH programs, including Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Guided Self-Help (CBT-gsh), are superior to wait-list conditions and may be equivalent to specialty treatments in reducing binge eating and related eating disorder symptoms. Reviews investigating GSH and Pure Self-Help (PSH) for BED and BN agree on the utility of GSH and PSH, and recommend further investigation of self-help approaches (Perkins, Murphy, Schmidt, & Williams, 2006; Stefano, Bacaltchuk, Blay, & Hay, 2006; Vocks et al., 2010). Perkins et al. (2006) found no significant differences between GSH or PSH and other formal, specialty psychological treatment approaches at post-treatment or follow-up on binging or purging, other eating disorder symptoms, level of interpersonal functioning, or depression. In addition, while GSH and PSH were not significantly different than a wait-list condition at post-treatment on binging and purging, they yielded significantly greater improvements at post-treatment on other eating disorder symptoms, psychiatric symptomotology, and interpersonal functioning. Moreover, no significant differences were found in dropout rates between GSH and formal therapist-delivered psychological therapies, or between GSH and PSH (Perkins 2008; Stefano et al., 2006; Vocks et al., 2010). A recent trial compared CBT-gsh, IPT, and BWL and found no significant differences among the three treatments in remission from binge eating, reduction in number of days of binge eating, or no longer meeting DSM-IV criteria for BED at post-treatment and 1-year follow-up (Wilson et al., 2010). While IPT and CBT-gsh were not significantly different from one another at 2-year follow-up, both were superior to BWL. Other studies have similarly documented GSH’s durability of binge eating reduction through follow-up (Carter and Fairburn, 1998; Peterson et al., 2001). Perkins et al. (2006) concluded that (a) evidence, though limited, supports the use of self-help in the treatment of recurrent binge eating disorders and (b) insufficient evidence supports any particular self-help approach (e.g., PSH or GSH) over another, and (c) additional self-help research, including randomized controlled studies which apply standardized inclusion criteria evaluation instruments and self-help materials, are needed. A third review of various guided and unguided self-help treatments for BED and BN concluded that self-help yields maintained improvements in eating disorder symptoms at follow-up (between 3 and 18 months post-treatment) (Sysko & Walsh, 2008). In addition, limited studies were found that implemented variations of GSH in a group therapy modality (Peterson et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 2001; Peterson et al., 2009). Thus, self-help is a promising, yet understudied approach to the treatment of BED.

Affect regulation in BED treatment

There is an extensive literature investigating the relationship between negative affect and binge eating that repeatedly cites significant associations between the presence of negative mood and the onset of a binge eating episode (Abraham & Beumont, 1982; Agras and Telch, 1998; Polivy & Herman, 1993; Stice and Agras, 1998; Telch and Agras, 1996; Stickney, Miltenberger, & Wolff 1999; Wegner, Smyth, Crosby, Wittrock, Wonderlich, & Mitchell, 2002). For example, negative mood was found to be significantly higher at pre-binge compared to non-binge times among women with BED, and participants attributed their binge episodes to mood more frequently than hunger or binge-abstinence violation (Stein, Kenardy, Wiseman, Dounchis, Arnow, & Wilfley, 2007). The affect regulation model of binge eating conceptualizes binge eating as an attempt to alter painful emotional states (Polivy and Herman, 1993, Linehan & Chen, 2005; Waller 2003; Wiser and Telch, 1999) and postulates that binge eating is maintained through negative reinforcement as it provides temporary relief from aversive emotions (Arnow et al., 1995; Smyth et al., 2007; Wiser and Telch, 1999). Stein and colleagues (2007) conversely, question the purpose of binge eating as relief from negative mood given their data indicating significant elevations in negative mood at post-binge times. However, one might postulate that binge eating’s temporary relief from pre-binge negative mood occurs only during the act of binging, and subsequently negative mood returns quickly, perhaps in greater force, upon the individual’s dawning self-awareness of the ‘damage done’ via the binge and subsequent feelings of guilt and shame. In this way, binge eating itself might be considered an ineffective coping strategy for pre-binge negative affect, thus explaining the increase in negative affect post-binge. Regardless of the time length of relief from negative affect that binge eating may provide, the literature agrees that negative affect often precedes binge eating and that more research on the role of binge eating to manage affect is warranted. In summary, data from previous research linking negative affect as a precipitant for binge eating, the compelling theory of the affect regulation model of binge eating, and the need for further studies investigating the use of binge eating for emotion management provide foundation for the rationale to incorporate emotion regulation strategies into BED treatments.

Rationale for development of a GSH BED intervention based on affect regulation model

There are then a number of reasons for further study of and treatment development for a BED GSH treatment based on affect regulation model of binge eating. Many recent reviews indicate that GSH is a promising treatment option for BED (Perkins & Schmidt, 2006; Perkins et al., 2006; Stefano et al., 2006; Sysko & Walsh, 2008; Vocks et al., 2010) however, all call for further GSH research, including studies comparing GSH to established interventions or credible comparison treatments, before more steadfast conclusions are drawn. While GSH is typically administered on an individual basis, group-based GSH offers a novel, viable, and even more cost-effective alternative although few studies in the literature were found that administered CBT-gsh in group format (Peterson et al., 1998; Peterson et al., 2001; Peterson et al., 2009). Last, to the writer’s knowledge, no existing BED GSH treatment has incorporated an affect regulation model of binge eating, which appears warranted given research linking negative affect and binge eating (Abraham & Beumont, 1982; Polivy & Herman, 1993; Arnow, Kenardy, Agras, 1992, 1995). Moreover, data linking negative affect with the onset of binge eating episodes supports the utility of affect regulation models of binge eating in intervention theory and application.

Integrative Response Therapy, a new GSH BED intervention

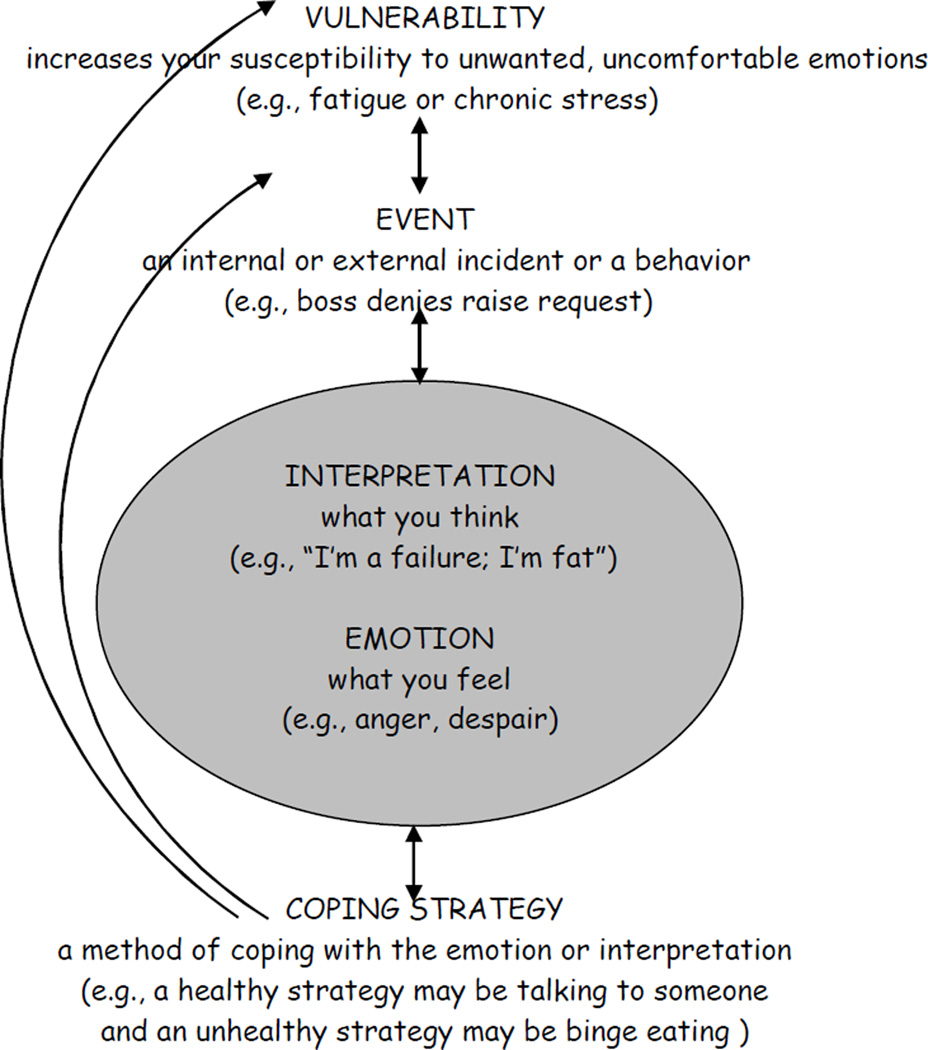

Integrative Response Therapy (IRT) is a group-based, GSH treatment program for BED that is primarily based on affect regulation theories of binge eating, while adding emphasis on cognitive restructuring techniques, reducing vulnerabilities and, when possible, negative events that contribute to problematic emotional responding and cognitions. The IRT model (Figure 1) postulates a theoretical pathway leading to and maintaining binge eating, and intervention areas to target in order to reduce the frequency of binge eating.

Figure 1.

Integrative Response Therapy Model

Note. Vulnerability=a predisposition/susceptibility to emotional upset or faulty interpretation that is prompted by a Physical (i.e., hunger, chronic stress), Interpersonal (i.e., argument with spouse, boss denies raise), and/or an External Event (i.e., rainy day, computer crashes) stimulus; Emotion=feeling; Interpretation=cognitive process of understanding and internalizing activated factors in the model; Coping Strategy=method employed to engage with, deny, avoid, and/or terminate previously activated factors in model (e.g., binge eating, exercise, journaling).

IRT model components

The core factors, also intervention points, in the model include: vulnerabilities, events, interpretations, emotions, and emotion coping strategies.

Vulnerability refers to being overly susceptible to any factor that could increase the risk of negative or unpleasant emotions, and therefore binge eating. IRT offers specific interventions for reducing common vulnerabilities in addition to general emotion coping strategies (described below) that are readily applicable to vulnerabilities.

Events are incidents that lead to subsequent interpretation and emotional response. Events can be external (e.g., argument with spouse, flat tire, hard day at work), internal (e.g., a headache), or a behavior (e.g., oversleeping, yelling, binge eating, being late to work). Events can be related to one another and/or occur in sequence and thus be additive in their impact on interpretations and emotions (e.g., tardy to important work meeting, forgot laptop with a presentation on it, and spill coffee on shirt). Vulnerabilities can increase the chance of a negative event and vice versa. In order to reduce the likelihood of unnecessary negative emotions and binge eating, IRT describes methods for (a) reducing negative events when possible, (b) improving management of negative events when they do occur, and (c) increasing positive events.

Interpretations represent how one ascribes meaning or significance to an event, or summarizes the experience of an event. Thus, they often occur after an event (although some interpretations may begin during an event). Interpretations and emotions have a cyclical relationship as they directly and repetitively influence each other. IRT teaches strategies to change overly negative and global interpretations into more accurate reflections in order to reduce unnecessary and unwanted negative emotions and thereby binge eating.

Emotions are affective responses accompanied by a physiological, often behavioral, and/or interpretive response. Again, IRT postulates that emotions have a direct and reciprocal influence on interpretations, are impacted by vulnerabilities and events, and are antecedents to an emotion coping strategy.

Emotion Coping Strategies can be any method, active or passive, constructive or potentially destructive, an individual employs to deal with (e.g., cope, avoid, distract, face) an emotion. Examples include: binge eating, drinking, avoidance, berating oneself, procrastination, excessive shopping, smoking, sleeping, being rude or testy with others, or seeking support, talking to a friend or therapist, exercise, addressing the problem head on, mediation, and relaxation. As the IRT model depicts, there is a direct reciprocal influence between emotion coping strategies and emotions. Thus, IRT emphasizes that using a destructive strategy (e.g., drinking, instigating arguments, binge eating) is likely to increase negative emotions and further risk of (additional) binge eating. Likewise, supplementation of a destructive strategy with a constructive one (e.g., seeking support, talking it through, soothing) will decrease both additional experience or exacerbation of negative emotions and further risk of binge eating. Emotion coping strategies are also a subtype of event and thus can re-trigger the entire cycle via emotions and interpretations and/or vulnerabilities and events (as indicated by the direct and arc arrows in model). IRT offers (a) various active and constructive emotion coping strategies, and (b) emotion induction and re-experiencing techniques to prompt use of such coping strategies to facilitate the replacement of binge eating with alternative, more effective emotion management tools.

RESPONSES is an acronym that represents the IRT emotion coping strategies which include: Reflect on alternative interpretations, Exercise, Start distracting, Problem solve, Open communication, get distaNce, Soothe, get cEntered, Social and/or pleasurable activity. Group participants are taught the specifics of how to apply these techniques, and use group to discuss triumphs and problem solve around barriers to success. The rationale for teaching emotion coping strategies is to offer behavioral and cognitive alternatives to binge eating that participants may not know or have previously underutilized.

Advanced Emotion Coping Training is an advanced emotion regulation technique in which participants are taught how to purposefully induce and experience an emotion and then work to reduce it via application of RESPONSES (which have been previously mastered). By creating these emotional experiments, participants fashion a situation that may have otherwise induced binge eating but now, in a controlled pre-mediated manner within a safe environment, they have an opportunity to apply more effective and healthful coping strategies. Benefits of this technique include (1) increased insight into which specific emotions may be ones’ most troublesome triggers for binge eating, (2) improved familiarity, level of comfort with, and mastery of using the RESPONSES strategies with a real-time emotional experience, (3) principal establishment of and confirmation that one can successfully use alternative healthful methods aside from binge eating to cope with aversive emotions, and thus, (4) improved self-efficacy and motivation for binge eating cessation. The rationale for emotion induction and re-experiencing training is (a) based in evidence from the anxiety literature that this type of induction and exposure exercise coupled with previously mastered anxiety reduction techniques has resulted in reduced intensity and frequency of subsequent anxiety and/or improved ability to effectively manage anxiety in future similar situations; and (b) that it is an intervention consistent with IRT as a affect-regulation based model.

Session format

IRT’s10 group sessions last 60 minutes each and are administered over the course of 16 weeks with the first 4 sessions occurring weekly and remaining 6 sessions biweekly. IRT’s first six and last two sessions are structured (i.e., include worksheet review and teach new material) in order to ensure review and encourage discussion about important concepts at the outset and cessation of treatment. IRT’s sixth and seventh group session topics are ‘participant driven’ or determined by questions and problems raised independently by participants. The rationale for these two group session topics being participant- rather than therapist-determined is that it reinforces the GSH nature of the treatment via (1) compelling participants to be relatively independent and take an active lead role in facilitating their own recovery from binge eating, (2) decreasing reliance on the therapist to generate discussion and identify problem areas, and (3) encourage reliance upon the treatment manual rather than the therapist. Thus, participants are encouraged to bring their questions and concerns (e.g., regarding IRT concepts, skill application, barriers to success, and worksheets) to group for discussion. For pilot testing purposes, the group therapist was this writer however IRT was designed to have all group therapy sessions lead by non-doctorate degree holding therapists (with bachelors, associates, or a masters degree) who do not have specialty training in eating disorders.

Session 1(week 1): Welcome, Discuss the Pros & Cons of Stopping Binge Eating, Introduce IRT Model

The purpose of Session 1 is to welcome and introduce the group members to each other, discuss participants’ pros and cons of stopping binge eating, and orient the participants to IRT and the nature of a GSH treatment program. Participants are given the IRT manual and instructed to complete the “Identifying Pros and Cons of Stopping Binge Eating” worksheet in Session 1. Participants’ responses on the worksheet are then collaboratively discussed – the purpose of which is to increase motivation for treatment compliance while acknowledging the role binge eating has served in their lives. The therapist introduces the IRT model and applies participant provided binge episode examples to model. Last, participants are instructed to read the entire manual prior to Session 2.

Sessions 2–6 (weeks 2–8): Teach the IRT Model & Change Strategies

The therapist introduces and describes each component of the IRT model, interventions related to each model component, and elicits and applies participant provided binge episode examples to the model in order to highlight the model’s personal relevance and the reinforcing nature of binge eating. Didactics for sessions 2–6 include RESPONSES, Advanced Emotion Coping Training, Events, Vulnerabilities, and a comprehensive review integrating all components, respectively.

Sessions 7–8 (weeks 10–12): Participant Choice

Session topics are determined by participants. Topics may be related to the IRT model of binge eating (e.g., emotions, interpretations, vulnerabilities), concept clarification, barriers to effective and timely use of IRT techniques, efficient use of worksheets, and general problem-solving (e.g., how to eat in social situations).

Session 9 (week 14): Review/Sticking with What Works

The 9th session provides a structured and comprehensive review of IRT’s concepts and techniques. The therapist also encourages participants to identify patterns in their binge eating and IRT technique use, and continue regular use of IRT methods they have found most helpful.

Session 10 (week 16): Planning Ahead/Relapse Prevention

The final session offers techniques for success maintenance via planning ahead and relapse prevention, and effectively and swiftly coping with lapses.

IRT group therapy illustrations: Transcription excerpts from sessions 1 and 3

Session 1: Therapist introduces the IRT model (Note: In this session the therapist describes the IRT model from the bottom-up (i.e., from coping strategy up to vulnerability); The IRT Model is depicted in Figure 1)

THERAPIST: Let's talk now about the IRT model. Overall, what we are looking at here is the relationship between negative emotions and binging as a way to cope with them. Let's draw this out on the board [draws]. First, at the bottom of the model is 'coping strategy' so let's put binge eating here as it is an example of a coping strategy that we'll focus on as a core part of this treatment. Now, let's see now how this model works with an example of someone preparing for a job interview. So let's say this person is experiencing anxiety [points to emotions section of model] as a negative emotion, and uses binging to try to reduce that feeling or ignore it.

Also, there is a very important relationship between our feelings and the way we think, called 'interpretations'. For example, this person’s interpretations that impact the emotion of anxiety might be "I'm going to fail; this interview will be terrible". Can you notice that if this person thinks this way that they're likely to feel more anxious?

GROUP MEMBERS: [collectively] Sure. Yes.

THERAPIST: Right. Now as this person is feeling more and more anxious, what types of interpretations might they be having?

GROUP MEMBER 1: More of the same - like a vicious cycle.

THERAPIST: Right - exactly. The interpretation “I'm going to fail” and the feeling of anxiety feed each other in a vicious cycle. So these two things really influence each other a great deal [points to reciprocal interaction between emotion and interpretations on board]. Therefore, the interpretations also influence the coping strategy of binge eating down the line [points to this relationship, as depicted in arrows, in the model]. Both the emotions and interpretations can influence the coping strategy.

There is an event that happens before there is the interpretation and emotion. So [in other words], you are interpreting something; the thoughts result from some source. In this example, the person is going to have a job interview. Has everyone here had some type of interview? They can be kind-of nerve racking, right? This person’s event is the job interview, he or she has interpretations “I’m going to fail” which increases anxiety and additional critical interpretations and ultimately, this person is more and more likely to deal with the anxiety via binge eating [correspondingly points to each factor in the model and highlights the interaction between factors]. Is this sounding familiar? Does it resonate with folks?

GROUP MEMBERS: [collectively] Yep. Yes.

THERAPIST: There is another part to this model. Even before the event, we believe that there is a vulnerability that exists [points to vulnerability]. When I say vulnerability – well, its means just what it sounds like. It refers to something that sets you up to have a harder time than you might normally or otherwise. An example of vulnerability in this case is that the person is really tired. If you’re really exhausted, how does that impact your ability to cope with something, like a job interview, that might normally be really hard?

GROUP MEMBER 2: It makes it harder.

THERAPIST: Yes, it reduces your ability to handle the situation as you might ideally like or makes doing so harder overall. [Therapist then reviews the definition and flow of model factors again, using the job interview example.] So, what do you guys think? We’re not completely done yet by the way, but we’ve covered the first core part of the model. How does it sound so far?

GROUP MEMBER 1: Unfortunately, it sounds very familiar.

GROUP MEMBER 3: Yea, like my life. I mean I don’t think you always think clearly about these things and can identify how you’re vulnerable, interpreting, etcetera. I think stuff happens and this [points toward model] is the breakdown of it. [Right now] I think we feel like we’re along for the ride; like I’m powerless and the inevitable end is binging.

THERAPIST: That is an excellent point that leads me into talking about why we are breaking it down like this. Do you guys have any ideas about why it would be helpful to take something that feels like ‘its just happening to you’ and break it down like this, into more understandable pieces?

GROUP MEMBER 2: Well, there are a couple of different places where you can try to stop it. Right?

THERAPIST: Great point. Can you give us an example?

GROUP MEMBER 2: Well, I see you could come up with a different coping strategy. Which I think, probably, we all have tried. And so, um, you know, you could probably come up with different interpretations or … How can you make that arrow go in a different direction [points to board]? How could you, you know, insert something else there?

THERAPIST: Ok, like inserting something else for interpretation and see how it impacts the rest?

GROUP MEMBER 2: Yea, exactly. Then, we’re always going to have events. We are always going to put into a vulnerable position and we’re always going to have an emotion…

THERAPIST: I want jump in here if I can. I hear what you’re saying and everyone seems to be getting to one important point which is yes: there are multiple places to intervene. And I heard you saying that you are ‘always going to have events and vulnerabilities and emotions’ but we can do certain things to intervene at every single level in the model. We are going to spend this treatment looking at how we can impact all these different things. Hopefully that provides, even though this is a vicious cycle, some faith and hope that there are many different ways to address this problem [points to binge eating on board]. And I think that’s a really good thing!

What I haven’t done yet is draw these arrows from binge eating back up to the other factors [draws on board]. So it doesn’t just end in binge eating but rather comes back up and influences in the other direction. Someone earlier mentioned that they feel guilty after a binge or think “Oh God, what did I do?

GROUP MEMBER 4: Yes, there should be an arrow from binge eating back up to anxious.

THERAPIST: Yes! Absolutely, in fact there is a bidirectional arrow in between emotions and binge eating and interpretations and binge eating. That’s a very important point. Also, the arrow goes back up to the event [points to arrow from interpretations and emotions back up to event]. Using our example: if you go into an interview thinking “I’m going to fail”, how do you think the actual interview is going to go?

GROUP MEMBERS: [collectively] Not good. Bad.

THERAPIST: Yes, probably not very well. So there is another arrow here for that. If you have this kind-of frustrating job interview and its going to wear you down, then you might be even more vulnerable to a subsequent event. That’s why we have this arrow here [points to arrow from event back up to vulnerability]. So this is another really important point – these factors all play into each other.”

[Therapist moves on to discuss additional model attributes and apply participant provided binge examples to the model].

Session 3: Advanced Emotion Coping Training

THERAPIST: Advanced Emotion Coping Training [is an emotion regulation exercise that] asks you to, step-by-step, imagine yourself in a situation that heightens an emotion that triggers binge eating for you. And then to do something different instead of binging. Try using some of the RESPONSES instead. So this will challenge you. It will really help you build your confidence that you can use the RESPONSES, that you can do something different than binge eating in response to these emotions, prove to you that you know how to do it, and it can make you really feel good about yourself.

I’ll walk you through it step-by-step and it’s also in the book on page 28. First, Step 1 is to rank your emotions. Find out which are the most triggering for you. And Worksheet 3 is going to be helpful for that. That’s where you listed the emotions that tend to trigger binges or binge urges, and at which level of intensity [from 0, not present at all, to 10, the most intense feeling possible]. [For example] my number one emotion is boredom. My number 2 emotion is anxiety. Boredom might be at an 8 for intensity, anxiety at a 6. The idea is to pick an emotion and intensity level that allows you to be successful at this exercise. We want it to be challenging enough, but not so challenging that it feels overwhelming. Challenging enough so that it feels like you can actually do it. Later on, once you get the hang of this, and you feel a little more confident in how to do the exercise, you can crank it up and induce the [more intense] emotion.

Step 2 is to Set the Stage. So you’ll pick where to do it. At first, when you’re just learning how to do this, it’s best to not do it around food. Do it maybe in the park or your parked car. Or, um, maybe even on a walk if you can focus like that. Or in your bedroom. Somewhere away from access to food or where it’s harder to get to that food. Also, you’re going to pick when to do it. This is really individual. Some people take a half an hour and do that, and that’s fine. But some people may need more time to do it. So really think about when is a good time in your day to do this. But you’ll need enough time to imagine a scene, induce the emotion, allow yourself to experience the emotion, and then use RESPONSES to bring down that emotion.

The next step is actually inducing the emotion. There’s a couple of ways to do this. One is using your memory of a specific event. So maybe the time my cat was lost, and that made me feel distressed and sad and worried. And I can remember what kind of day it was. Maybe it was in the evening; maybe it was around this time of year. And I can picture where I was, what I was wearing, and maybe any sensations I had at that time. [These specifics] will help you get into that moment a little bit more. The more I can remember about that event, the more realistic it will be. The more easily I will experience the same emotion that I did at that time. We want to induce some of those emotions, maybe not too intense at first, but wanting to feel the emotion associated with that memory

GROUP MEMBER 1: But not necessarily an emotion at a 10 intensity?

THERAPIST: Right. So picking what memory it’s going to be is really important.

GROUP MEMBER 1: And then doing something…

GROUP MEMBER 2: And then feel it, then what? Then what?

GROUP MEMBER 1: You do something different, besides going into the kitchen.

GROUP MEMBER 3: Then you use one of these [RESPONSES] on page 27.

THERAPIST: Yes. All of those [RESPONSES] are options you can use.

Also, if you don’t have a memory connected with the emotion you are trying to induce, you can read [the examples on] page 30 and that will help you [induce an emotion]. But we do encourage you to try to draw from your own experience because more likely that’s going be more effective in inducing the emotion. But [reading] these examples are an option as well.

So, you’ll also need to plan out which RESPONSES you’re going to use to effectively cope with, sit with, and reduce the emotion after you’ve induced it. For example, I sit in the park and I imagine the time my cat was lost, I want to know what I’m specifically going to do to help myself feel better. Maybe it will be mindfulness, maybe it will be taking a walk, maybe it will be calling a friend. I want a few options of things that are likely going to make me feel better. So that I have it all planned out. Do these steps make sense to everyone?

GROUP MEMBERS: [collectively] Yes. OK.

THERAPIST: So, again, you’re actually going to bring an emotion up to whatever level you want it to be using either your memory or the examples on page 30. Then you’re going to tolerate it there at that level without letting it go any higher, then you’re going to bring it back down again by doing something new, like the RESPONSES.

Last, you’re going to reflect on how it went. Worksheet #6 will help you do that. [For example], was it hard to bring the emotion up or bring it back down? Maybe you picked an emotion that wasn’t quite high enough and you didn’t really feel much. Or maybe you picked one that was too high and it was overwhelming. And then you’re going to bring [the completed worksheet] into group. And we’re going to discuss how it went.

Also, remind yourself of the reasons to do this - it’s going to increase your mastery of RESPONSES, it’s going to help build confidence that you can reduce an uncomfortable emotion without binging. It’s a pretty powerful technique. It will really make a difference for you if you figure out how to use it in a way that works for you.

Let’s think about some things that might get in the way of potentially practicing this week. What do people anticipate getting in the way of trying this or making this hard?

GROUP MEMBER 4: Kids.

THERAPIST: What about kids? Will you need some time away from them to do this exercise? But you could also use them as part of your RESPONSES [to bring down the emotion] - play with them, take them somewhere fun, laugh with them. What else?

GROUP MEMBER 2: Procrastination.

GROUP MEMBER 3: Overwhelmed. Not that I’m not going to do it but…

THERAPIST: So let’s think of what can we tell ourselves to increase motivation to do this?

GROUP MEMBER 3: It’s a way to getting to the end product that we want.

THERAPIST: That it will help, basically.

GROUP MEMBER 4: I think I’ll get stuck in the emotion, rather than move through the emotion.

THERAPIST: If you’re worried about getting stuck, I encourage you to start with an emotion that is less challenging for you, that feels less overwhelming, and really plan out what [RESPONSES] to do. Really think about what you’re going to do. What has worked in the past besides binging, to help you calm down and feel better? Maybe you need one of the RESPONSES that’s more powerful in terms of distracting you. I don’t know what it will be that works best for you. What works for you usually?

GROUP MEMBER 4: That’s why I’m here. Not a lot works. [laughs]

THERAPIST: Okay so maybe you need to practice a few more of the RESPONSES before you start the Advanced Emotion Coping exercise. Maybe you need to practice and discover which of the RESPONSES will really work for you. Maybe calling a friend that you know will listen. And then having a backup plan in case she doesn’t answer, right?

Okay what else might get in the way of trying this?

GROUP MEMBER 4: I don’t even feel emotions sometimes. I’ve been through enough things in life that I’m sorry to say, and so it’s really shut me down. That’s going to get in the way.

THERAPIST: So you’re worried that you’re not going to [successfully] induce [and feel] the emotion? If you’re worried about that, you could use the examples in the book and really pay attention to [sensations in] your body and your interpretations about the emotion. So you might want to look through these [examples] and see which can help.

What else might get in the way?

GROUP MEMBER 2: Part of me loves being unconscious. And binging is a manifestation of being unconscious. And these exercises, I can feel, are trying to fix my brain. And part of me is grateful for the manual, and part of me is like it’s taking away my blanket. Now I have to think about these things. It’s like restructuring my brain. Where previously, the whole beauty of the binge is to go into a food cloud, and become unconscious.

THERAPIST: Yes, you’re right – I think you’re saying its hard work? [It may help to review]: What is my motivation for wanting to change? What are the Pros and Cons of change? That will help you face all the things that get in the way of trying this thing that is hard work. This is new. We are making you think about it.

Novel aspects of IRT

While IRT integrates important therapeutic aspects of affect dysregualtion theories of BED similar to DBT-BED and cognitive restructuring techniques similar to traditional forms of CBT (i.e., CBT for depression), it also has numerous novel aspects including that it:

Is an affect-regulation and group-based GSH BED intervention.

Primarily focuses on emotional interventions for binge eating cessation yet integrates cognitive and behavioral techniques.

Teaches emotion induction and re-experiencing to prompt use of effective emotion coping responses. This augments participants’ self-efficacy and establishes experience in responding to aversive emotions healthfully (i.e., without binge eating).

Is multifaceted; it teaches techniques for (1) binge antecedents (i.e., reducing vulnerabilities to overwhelming emotions and faulty cognitions, managing binge urges, and when possible, reducing negative events), and (2) binge repercussions (improving emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses to binge episodes).

Is designed specifically for BED unlike most existing treatments which were originally designed for another psychiatric or medical concern (e.g., CBT and IPT for depression, DBT for Borderline Personality Disorder, BWL for weight loss).

Offers a model readily applicable to psychological concerns aside from binge eating (e.g., interpersonal disputes, anxiety, etc.).

Unlike existing specialized BED treatments (e.g., CBT, IPT, or DBT-BED), IRT is designed to not require a specialty trained therapist or time-intensive administration (e.g., 6 months of up to 2-hour weekly sessions to administer).

Via the GSH format, IRT works to deliberately and simultaneously decrease participant reliance on therapist and encourage participants to take an active lead role in the recovery process (i.e., participant determines where they need assistance rather than relying on therapist to make a suggestion or direct all sessions).

Similarities and differences between IRT and other BED treatment approaches

IRT and other well-known treatments share components common to many therapeutic approaches for BED (e.g., CBT, IPT, DBT-BED) including: manual-based, focus on cessation of binge eating, therapist is active and directive in session, import placed on rapport between therapist and patient, homework (in the form of behavioral tasks and/or worksheets) is encouraged, therapy sessions include both reflective and didactic/psychoeducational components, and motivation and relapse prevention are addressed.

IRT and CBT-gsh

CBT-gsh is a frequently used manual-based form of GSH that has demonstrated efficacy. As originally conceptualized by Fairburn (Fairburn, 1995), CBT-gsh typically offers participants a book on overcoming binge eating accompanied by six to twelve, approximately 30 minute, individual therapy sessions (Carter & Fairburn, 1998; Grilo & Masheb, 2005). IRT and CBT-gsh differ in their theoretical postulates of primary and secondary binge eating precipitants and consequently, in their type and sequence of interventions to achieve abstinence. Such distinctions may yield significant differences in binge eating abstinence rates and patient acceptability. While IRT postulates that binge eating is primarily an attempt to alter, avoid, suppress, or otherwise cope with aversive emotions and/or faulty cognitions, CBT-gsh proposes that binge eating results from behavioral factors, specifically problematic eating patterns. This key theoretical distinction accounts for the two treatment’s differences in intervention focus and sequence. Specifically, IRT first works to teach effective emotion coping and cognitive restructuring, while CBT-gsh primarily focuses on rectifying behavioral triggers of binge eating (i.e., eliminating dietary restriction and establishing regular patterns of eating). Secondary intervention targets for IRT include vulnerability reduction and negative event management, whereas CBT-gsh addresses concerns about food, weight, and shape. IRT therefore, does not require the regular self-monitoring and behavioral modification of food intake that is the crux of CBT-gsh treatment. CBT-gsh, unlike IRT, does not directly provide emotion coping strategies for overcoming urges to binge eat. In summary, IRT and CBT-gsh differ in their theoretical postulates of primary and secondary binge eating precipitants and consequently, in their type and sequence of interventions to achieve abstinence.

IRT and DBT-BED

While both IRT and DBT-BED acknowledge binge eating as an attempt to alter aversive emotional states and postulate that binge eating is maintained via negative reinforcement, or the temporary relief from unpleasant emotion, there are some critical therapeutic differences between the two treatments. First, IRT is a GSH treatment and DBT-BED is a specialty treatment whose administration (as detailed in Safer, Robinson, Jo, 2010) requires a PhD level therapist and up to 6 months of 2 hour long sessions to administer. Unlike DBT-BED, IRT places therapeutic emphasis on emotions and/or cognitions as binge eating precipitants and therefore places greater weight on cognitive restructuring techniques. IRT purposefully provides substantially fewer skills than DBT-BED in order to streamline teaching and reduce patient burden warranted within the shorter treatment delivery timeframe. IRT teaches emotion induction and re-experiencing to prompt use of effective emotion coping responses and DBT-BED does not. IRT does not employ chain analyses and diary cards characteristic of DBT-BED. Last, IRT does not require the commitment to 100% binge abstinence obtained from DBT-BED participants in session 1.

IRT and IPT

IPT’s theoretical basis is quite different from IRT’s as the former conceptualizes each case within one of four social domains (grief, interpersonal role disputes, role transitions, and interpersonal deficits) and then directly addresses these social and interpersonal deficits to reduce binge eating. IPT is not based on an affect-regulation model of binge eating nor does it provide direction in cognitive restructuring.

Method

An uncontrolled preliminary study of IRT was conducted to test the feasibility of recruitment, treatment, patient adherence, and patient acceptability.

Subjects

A small sample of adults (n=16) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for BED participated in the study. Participants were recruited through flyers and clinic referrals for “treatment for binge eating.” Eligibility was assessed via an initial telephone screen followed by an in-person clinical interview, during which potential participants provided informed written consent. Men and women aged 18 and older who met DSM-IV research criteria for BED and lived or worked within commuting distance of the clinic were included. Exclusionary criteria were: 1) concurrent psychotherapy treatment; 2) unstable dosage of psychotropic medications over the three months prior to initial assessment; 3) regular use of purging or other compensatory behaviors over the past six months; 4) psychosis; 5) current alcohol/drug abuse or dependence; 6) severe depression with recent (e.g., within past month) suicidality; 7) current use of weight altering medications (e.g., phentermine); 8) severe medical condition affecting weight or appetite (e.g., insulin dependent diabetes, cancer requiring active chemotherapy); 9) current pregnancy or breast feeding; 10) imminently planning or undergoing gastric bypass surgery; and 11) lack of availability for times of group meetings and/or duration of study. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University Medical Center.

Assessment

Participants were asked to complete three assessments (baseline, post-treatment, and three month follow-up). The assessment battery was the same at all time points and included the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, Erbaugh, 1961), Emotional Eating Scale (EES; Arnow, Kenardy, & Agras, 1995), and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1979). Body weight was assessed on a balance beam scale, with the participant in lightweight clothing and shoes removed. Height was measured with a stadiometer. For both variables, the average of two measurements was used. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in meters). A satisfaction survey was administered at post-treatment to assess patient acceptability of treatment.

Treatment

All participants received IRT. Group sessions followed the aforementioned outline.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to summarize the sample characteristics and outcomes. T-tests, using completer analysis, tested differences on outcome measures between baseline and post-treatment, and baseline and three month follow-up. Cohen’s D effect sizes, based on Morris and DeShon's (2002) effect size equation for within subjects repeated measures (which corrects for dependence between means), were calculated for the primary outcome (number of binge days over the previous 28 days). Effect sizes were evaluated by the conventions: small=.20, moderate=.50, and large=.80 (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 16 adults, 88% (n=14) female, with a mean age of 51.1 ± 9.9 years and BMI of 31.2 ± 9.4 kg/m2. Subjects were 88% (n=14) Caucasian, 6% (n=1) Latino, and 6% (n=1) Asian. Seventy-five percent (n=12) of subjects were married, 19% (n=3) divorced, and 6% (n=1) widowed. Regarding education, 44% (n=7) completed at least one graduate degree, 25% (n=4) completed some graduate school, 19% (n=3) graduated from a 4 year college, 12% (n=2) completed some college or a 2 year degree. Over half of the sample was employed (57%, n=9), 19% (n=3) homemakers, 12% (n=2) retired, and 12% (n=2) unemployed. On average, participants were 17.3 ± 8.8 years old when first overweight, 17.9 ± 7.1 years old when they first began dieting, and 22 ± 12.9 years old when they reported beginning to binge eat.

Treatment and Assessment Drop-Out Rates

Of 16 participants, 4 (25%) dropped from treatment. Drops occurred after session 1 (two men whose reasons for dropping are unknown), 2 (because she believed her eating disorder was more advanced than other group members), and 4 (because she wanted to focus on weight loss rather than binge eating cessation). All participants who completed treatment completed post-treatment and follow-up assessments (n=12). Although participants who dropped from treatment were invited to complete post-treatment and follow-up assessments, only one completed post-treatment assessment. Thus, post-treatment and follow-up data were obtained from 81% (n=13 of 16) and 75% (n=12 of 16) of the original sample, respectively.

Outcome Measures

Abstinence rates (defined as zero objective binge episodes over the previous 28 days) were 54% and 67% at post-treatment and 3 month follow-up respectively. The number of binge days over the previous 28 days dropped significantly from baseline to post-treatment [14.44 (±7.16) to 3.15 (±5.70); t=7.71, p<.001; d=2.2] and from baseline to follow-up [14.44 (±7.16) to 1.50 (±2.88); t=5.64, p<.001; d=1.7]. All subscales from both the Eating Disorder Examination – Questionnaire and Emotional Eating Scale demonstrated consistent decline from baseline to post-treatment to follow-up. There were no significant changes in Beck Depression Inventory or Rosenberg Self-Esteem scores nor in weight or BMI. Post-treatment satisfaction survey data indicated that 100% of participants (n=13: 12 who completed treatment plus 1 who dropped) would recommend the program to a friend or family member in need. Table 1 outlines study results.

Table 1.

Results

| Measure | Baseline n=16 |

Post-Treatment n=13 |

3 Month Follow-Up n=12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinence | 54% (7/13) Abstinent | 67% (8/12) Abstinent | |

| 46% (6/13) Non-Abstinent | 33% (4/12) Non-Abstinent | ||

| Binge Days* | 14.44 (7.16)a | 3.15 (5.70)b | 1.50 (2.88)b |

| Binge Episodes** | 18.25 (10.78)a | 3.38 (6.20)b | 1.50 (2.88)b |

| EDE-Q | |||

| Restraint | 2.9 (1.56)a | 2.25 (1.78)b | 2.05 (1.70)b |

| Shape Concerns | 4.31 (1.21)a | 3.42 (1.79)b | 2.78 (1.41)b |

| Eating Concerns | 3.31 (1.63)a | 1.98 (1.65)b | 1.30 (1.36)b |

| Weight Concerns | 3.90 (1.31)a | 2.85 (1.79)b | 2.42 (1.25)b |

| BDI | 12.31 (8.56)a | 13.46 (12.43) | 10.67 (1.60) |

| Rosenberg | 22.73 (7.70)a | 21.62 (9.39) | 18.83 (8.44) |

| EES anger | 2.59 (.69)a | 1.81 (1.00)b | 1.44 (.93)b |

| EES anxiety | 2.24 (.85)a | 1.55 (1.05)b | 1.32 (.81)b |

| EES depression | 2.73 (.88)a | 1.95 (1.25)b | 1.63 (1.15)b |

| Weight (pounds) | 171.15 (37.83)a | 167.95 (37.44) | 164.60 (38.39) |

| BMI | 28.78 (7.16)a | 28.30 (7.27) | 27.72 (7.52) |

Note: Means in the same row with different superscripts represent statistically significant differences (p<.05);

=number of days with an objective binge episode over the previous 28 days;

=number of binge episodes over the previous 28 days; EDE-Q=Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; Rosenberg=Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; EES=Emotional Eating Scale; BMI=body mass index.

Discussion

BED, a chronic condition characterized by a combination of eating disorder pathology, co-occurring physical and psychiatric conditions, impaired psychosocial functioning, and association with overweight and obesity, is an eating disorder of clinical severity and a significant public health problem. GSH treatments for BED appear promising in terms of their capacity for public health impact. Specifically, GSH may be more readily disseminable to health care providers and accessible to patients than efficacious specialty treatments such as CBT and IPT given the latter's administration costs and time requirements. This is particularly important in light of recent data indicating the equivalence of CBT-gsh to IPT in remitting BED and associated symptoms (Wilson et al, 2010).

IRT, a new group-based GSH BED treatment, is based on the affect regulation model of binge eating and thus, primarily works to decrease binge eating by enhancing emotion coping skills. IRT’s secondary focus is on cognitive restructuring and reducing vulnerabilities that risk emotional overwhelm and problematic cognitions. IRT demonstrated preliminary evidence for significantly reducing binge episodes, and all EDE-Q and EES subscales, at 16 weeks post-treatment within a sample of 16 adults. Large effects were observed for reductions in binge days over the previous 28 days from both baseline to post-treatment (d=2.2) and baseline to 3 month follow-up (d=1.7).

Limitations of the present study should be noted. First, although IRT is designed to be administered by a non-specialty trained therapist, a Ph.D. level and specialty-trained therapist (A. Robinson) conducted therapy for the purpose of the present preliminary study. Thus, further data on IRT feasibility and efficacy when administered by a non-specialty trained therapist is warranted. Second, confidence in findings may have been strengthened with the use of a structured clinical interview (e.g., the Eating Disorder Examination) for major outcome variables instead of the EDE-Q. Third, data on response to treatment and treatment acceptability among those who dropped from treatment is limited given that only 1 of 4 participants who dropped from treatment completed a follow-up assessment and treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Also, confidence in inferences from statistical analyses is limited given the small sample size of the preliminary study. Study strengths include the development of and first iteration of investigation into a GSH intervention for BED based on affect-regulation models of binge eating, that is delivered in a relatively non-time intensive fashion. Also, despite the small scope, sample size and assessment battery, the study used well-validated and reliable self-report measures of outcome variables, and gathered three month follow-up data. All participants who completed treatment completed both post-treatment and three month follow-up assessments. Last, the present study’s 25% drop-out rate is within the range of 13–30% previously reported from BED treatment studies employing GSH (Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Stefano et al., 2006; Perkins et al., 2006; Striegel-Moore et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2010).

Investigation of the longer-term effects of IRT within a larger sample, and whether IRT leads to improvements in particular subgroups, is presently underway in an initial National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) funded randomized clinical trial.

Acknowledgments

Funding: National Institute of Mental Health: T32 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Postdoctoral Research Training T32MH019938

References

- Abraham SF, Beaumont PJ. How patients describe bulimia or binge eating. Psychological Medicine. 1982;12:625–635. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700055732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agras WS, Telch CF. The effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge-eating disordered women. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:491–503. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnow B, Kenardy J, Agras WS. Binge eating among the obese: A descriptive study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;15:155–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00848323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow B, Kenardy J, Agras WS. The emotional eating scale: The development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995;18:79–90. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199507)18:1<79::aid-eat2260180109>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce B, Agras WS. Binge eating in females: a population-based investigation. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1992;12:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Fairburn CG. Cognitive-behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998; 66:616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman P, O’Conner M. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:659–665. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Overcoming binge eating. New York: Guilford; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge eating disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:675–685. doi: 10.1037/a0025049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for eating disorders. In: Freeman A, editor. Encyclopedia of cognitive behavior therapy. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus MD, Wing RR, Ewing L, Kern E, Gooding W, McDermott M. Psychiatric disorders among obese binge eaters. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1990;9:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Mussell MP. Comorbidity and binge eating disorder. Addictive Behavior. 1995;20:725–732. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent groups designs. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:105–125. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munsch S, Biedert E, Meyer A, Michael T, Schlup B, Tuch A, Margraf J. A Randomized Comparison of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Behavioral Weight Loss Treatment for Overweight Individuals with Binge Eating Disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:102–113. doi: 10.1002/eat.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins S, Schmidt U. Self-help for eating disorders. In: Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE, de Zwaan M, Steiger H, editors. Annual Review of Eating Disorders. Oxford: Radcliffe; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M, Schmidt U, Winn S, Murphy R, Williams C. Self-help and guided self-help for eating disorders; Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2006;19 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004191.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Miller JP. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder: A comparison of therapist-led versus self-help formats. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24(2):125–136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<125::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Crow SJ, Thuras P. Self-help versus therapist-led group cognitive behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder at follow-up. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30:363–374. doi: 10.1002/eat.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA. The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1347–1354. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer FX. Medical hazards of obesity. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;119:655–660. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer FX. NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults-- the evidence report. Obesity Research. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Herman C. In: Etiology of binge eating: psychological mechanisms, in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM. Review and meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2008;16(9):2024–2038. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer D, Robinson AH, Jo B. Outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of group therapy for Binge Eating Disorder: Comparing Dialectical Behavior Therapy and an active comparison group therapy. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(1):106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.006. 10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Marcus MD, Lewis CE, Fitzgibbon M, Schreiner P. Prevalence of binge eating disorder, obesity, and depression in a biracial cohort of young adults. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:227–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02884965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Engel SG. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Devlin MJ, Walsh BT, Hasin D, Wing RR, Marcus MD, Stunkard A, Wadden T, Yanovski S, Agras WS, Nonas C. Binge eating disorder: A multisite field trail of the diagnonstic criteria. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1992;11:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Yanovski S, Wadden T, Wing R, Marcus MD, Stunkard A, Devlin M, Mitchell J, Hasin D, Horne RL. Binge eating disorder: Its further validation in a multisite study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;13:137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano SC, Bacaltchuk J, Blay SL, Hay P. Self-help treatments for disorders of recurrent binge eating: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(6):452–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RI, Kenardy J, Wiseman CV, Dounchis JZ, Arnow BA, Wilfley DE. What’s driving the binge in binge eating disorder? A prospective examination of precursors and consequences. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:195–203. doi: 10.1002/eat.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Agras WS. Predicting onset and cessation of bulimic behaviors during adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analysis. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Wilfley DE, Pike KM, Dohm FA, Fairburn CG. Recurrent binge eating in Black American women. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:83–87. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, DeBar L, Perrin N, Lynch F, Rosselli F, Kraemer HC. Cognitive behavioral guided self-help for the treatment of recurrent binge eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:312–321. doi: 10.1037/a0018915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickney MI, Miltenberger RG, Wolff G. A descriptive analysis of factors contributing to binge eating. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1999;30:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(99)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Walsh BT. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(2):97–112. doi: 10.1002/eat.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch CF, Agras WS. Do emotional states influence binge eating in the obese? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1996;20:271–279. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199611)20:3<271::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch CF, Agras WS, Rossiter EM. Binge eating increases with increasing adiposity. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1988;7:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, Rustenbach SJ, Kersting A, Herpertz S. Meta anaylsis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;2010; 43:205–217. doi: 10.1002/eat.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller G. The psychology of binge eating. In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD, editors. Eating disorder and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner KE, Smyth JM, Crosby RD, Wittrock D, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. An evaluation of the relationship between mood and binge eating in the natural environment using ecological momentary assessment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;32(3):352–361. doi: 10.1002/eat.10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT. Psychological Treatment of Eating Disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:439–465. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grio CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;62:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser S, Telch C. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge-eating disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55:755–768. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199906)55:6<755::aid-jclp8>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski SZ. Binge eating disorder: current knowledge and future directions. Obesity Research. 1993;1:306–324. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]