Abstract

This study examined the interplay of parental racial-ethnic socialization and youth multidimensional cultural orientations to investigate how they indirectly and directly influence youth depressive symptoms and antisocial behaviors. Using data from the Korean American Families (KAF) Project (220 youths, 272 mothers, and 164 fathers, N = 656), this study tested the relationships concurrently, longitudinally, and accounting for earlier youth outcomes. The main findings include that racial-ethnic socialization is significantly associated with mainstream and ethnic cultural orientation among youth, which in turn influences depressive symptoms (but not antisocial behaviors). More specifically, parental racial-ethnic identity and pride discourage youth mainstream orientation, whereas cultural socialization in the family, as perceived by youth, increases ethnic orientation. These findings suggest a varying impact of racial-ethnic socialization on the multidimensional cultural orientations of youth. Korean language proficiency of youth was most notably predictive of a decrease in the number of depressive symptoms concurrently, longitudinally, and after controlling for previous levels of depressive symptoms. English language proficiency was also associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms, implying a benefit of bilingualism.

Adolescence is a unique life phase marked by dramatic physical and psychological changes and an increased vulnerability to behavioral and emotional problems (Costello, Copeland, & Angold, 2011). Adding further complexity to this period, minority children must resolve their racial-ethnic1 identity and cultural orientation while learning to navigate both overt and subtle structural inequality and racial-ethnic discrimination (Garcia Coll et al., 1996). During adolescence, youth interact with environments outside the home more regularly, increasing their risk of experiencing discrimination. In developing a positive and healthy sense of self, minority youth must also defy negative and/or unsubstantiated racial stereotypes and prejudices (Cross Jr., 2003; Garcia Coll, et al., 1996). However, when youth defy stereotypes, they risk being targeted for bullying (Peguero & Williams, 2011), which is consistent with research showing that individuals breaking stereotypes are routinely penalized socially (Phelan & Rudman, 2010). Thus, the minority adolescent’s process of racial-ethnic identity and cultural orientation development can be stressful and can further heighten vulnerability to negative outcomes.

However, family can play a crucial role in shaping these outcomes, for example, by transmitting information regarding race-ethnicity and teaching their culture of origin to their children (Marshall, 1995). The literature examining the interplay of race-ethnicity and culture within the family context has grown rapidly over the past few decades, encompassing areas of racial-ethnic socialization, racial-ethnic identity development, cultural orientations, and the impact of racism and discrimination. Yet, despite a consensus among scholars on the importance of race-ethnicity and culture in the family contexts, empirical research remains scant (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006; Spencer, 1983).

Moreover, most studies in this area focus on African Americans and just a few on Latin Americans (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006), so empirical research examining the role of race and ethnicity among Asian American families—the fastest growing racial-ethnic subpopulation in the U.S.—is seriously limited. For example, only a handful of studies have examined the effect of racial-ethnic socialization on youth outcomes among Asian American youth and young adults (e.g., Brown & Ling, 2012; Tran & Lee, 2010). Slightly more studies have focused on cultural orientations (such as assimilation to the mainstream culture or preservation of the culture of origin) and their impact on youth development (e.g., Benner & Kim, 2009).

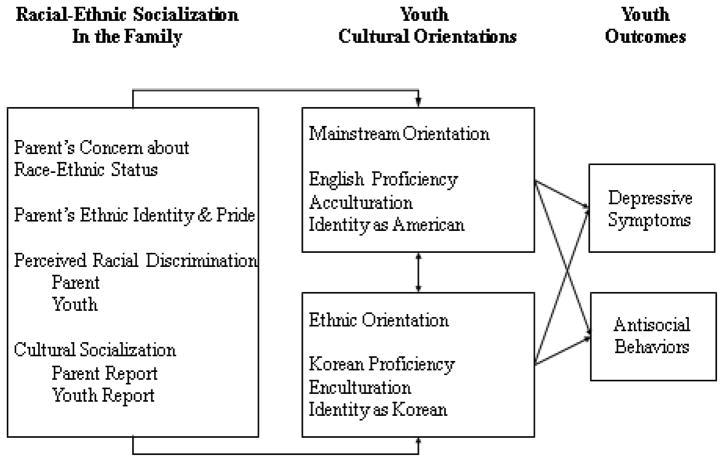

Furthermore, although numerous aspects representing race-ethnicity and culture in the family contexts (such as cultural socialization, racial discrimination, and cultural orientations) are likely to interact with one another to influence youth development, existing studies have examined only fragments of the relationships instead of looking at the interplay of these constructs simultaneously. Of the few that have examined the interplay of these constructs, most have focused on the buffering role of the racial-ethnic identity of youth (Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012) and none have examined the comprehensive dimensions of cultural orientations. This study aims to begin filling this gap in our knowledge by testing a path model (Figure 1) with youth and their parents from one of the major Asian American subgroups, Korean Americans.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

Racial-ethnic Socialization in Asian American Families

Racial-ethnic socialization is broadly defined as the transmission from adults to children of information regarding race-ethnicity that is verbal or nonverbal, deliberative or unintended, and proactive or reactive (Caughy, O’Campo, & Randolph, 2002; Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006). It is not only a critical and routine part of childrearing (Caughy, et al., 2002) but, for minority parents, it is also a parental task and responsibility required to raise healthy children in a society that poses additional risks to minority children (Evans et al., 2012). Hughes and her colleagues (2006) summarize racial-ethnic socialization in the literature as consisting of several components including cultural socialization, preparation for bias, promotion of mistrust, egalitarianism and silence about race.2

Cultural socialization, one of the most prominent aspects of racial-ethnic socialization, is “parental practices that teach children about their racial or ethnic heritage and history; that promote cultural customs and traditions; and that promote children’s cultural, racial, ethnic pride, either deliberately or implicitly” (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006, p. 749). Cultural socialization is particularly germane to Asian Americans and relatively prevalent across all cultural minority families (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006), whereas the prevalence of other components (for example, preparation for bias, promotion of mistrust and so forth) varies across different racial-ethnic groups. Of the handful of studies on this population, evidence suggests that transmitting messages about concerns of discrimination and racial-ethnic status is important but not as prevalent as messages on cultural socialization (Tran & Lee, 2010). In addition, Asian Americans such as Japanese Americans use egalitarianism more than preparation for racial discrimination and promotion of mistrust (Nagata & Cheng, 2003). In general, immigrant parents emphasize cultural experience and socialization (Benner & Kim, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004), whereas nonimmigrant minority parents, like African Americans, focus more on minority experience (Marshall, 1995). Korean American parents report proactively engaging in cultural socialization of their offspring, such as speaking in Korean to children and serving native foods at home (Choi & Kim, 2010). In this study, we examine cultural socialization in the family and its relations to youth cultural orientations and developmental outcomes.

Racial-ethnic socialization is highly contextual and dynamic, with both parent and child factors contributing to the effective transmission of salient messages on race-ethnicity (Hughes & Johnson, 2001). As recipients of discrimination and prejudice, parents of color are often concerned about their children growing up in an unfavorable environment that may even be hostile to them because of their race-ethnicity (Marshall, 1995; Peters, 1985). For example, African American mothers expressed grave concerns about the challenges of raising healthy children in the face of racial barriers (Peters, 1985), and Korean American parents reported sharing similar worries (Choi & Kim, 2010). Even if parents do not implement explicit strategies of racial-ethnic socialization, their concerns would influence their behaviors and attitudes, and subsequently their children, because racial-ethnic socialization includes nonverbal, implicit, and unconscious socialization regarding race-ethnicity (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006; Peters, 1985).

Parents’ own racial-ethnic identity also shapes racial-ethnic socialization messages and practices within the family context (Lalonde, Jones, & Stroink, 2008). For example, Thomas and Speight (1999) found that African American parents reporting a strong racial identity were more likely to report that racial socialization was critical to preparing their children to be successful. Hughes (2003) found that parental racial-ethnic identity was a particularly strong predictor of racial-ethnic socialization among Latino parents. In a similar manner, Korean immigrant parents are known for their high levels of ethnic pride and strong solidarity, to the point of being the least acculturated and the most socioculturally isolated ethnic group (Min, 2010). However, few empirical studies document how parental high ethnic pride and low acculturation influence the cultural orientations of Korean American youth.

Empirical evidence suggests that parents’ own experiences of racism and discrimination affect their beliefs and attitudes about race-ethnicity (Hughes, 2003) as well as their behavioral practices in preparing children (Neblett, et al., 2012). Specifically, parents who have experienced racial discrimination and have recognized that their own racial-ethnic group is not favored by the larger society are more likely to implement racial-ethnic socialization to prepare their children for a possible negative experience (Hughes, 2003). In addition, the experience of racial discrimination by youth would also likely influence their cultural orientations (Deng, Kim, Vaughan, & Li, 2010; Neblett, et al., 2012; Quintana, 2007; Ying, Lee, & Tsai, 2000). Asian American youth experience racial-ethnic discrimination that is systematically different from what other marginalized racial-ethnic groups experience. Asian American youth report the highest level of racially-ethnically motivated peer harassment and bullying (Rosenbloom & Way, 2004). In this study, we examine whether youth and parent’s experiences of racial discrimination influence cultural orientations and indirectly youth outcomes.

Youth Cultural Orientations

Most Asian American youth are children of immigrant parents. Like many youth of immigrant families, Asian American youth must negotiate between preserving their parental culture and adopting the mainstream culture. The process of cultural adaptation was originally conceptualized as a linear, unidirectional, and irreversible process in which cultural minorities assimilate into the dominant White culture, gradually shedding their culture of origin (Gordon, 1964). Cultural adaptation is now understood as more complex, dynamic, and multidimensional process (LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993). However, with only a few exceptions (e.g., Benner & Kim, 2009; Ying, et al., 2000), it is not yet common to empirically examine multiple cultural orientations simultaneously. In this paper, we use the term cultural orientations to signify the multidimensional nature of the process in which a cultural minority can simultaneously possess multiple repertoires of different cultures and be equally competent in multiple cultural settings. Specifically, we examine it as a dual process of cultural orientations to the mainstream culture (mainstream orientation) and to the heritage culture (ethnic orientation) as distinct constructs.

Researchers combine or use interchangeably different aspects of cultural orientation, such as language competence, behavioral participation in cultural activities, and racial-ethnic identity. However, they are distinct and independent aspects of cultural adaptation (Ward, 2001). For example, one’s inability to speak one’s heritage language does not necessarily mean a low level of racial-ethnic identity. Of the various aspects of cultural orientation, racial-ethnic identity indicates a much more conscious endorsement of one’s race-ethnicity than the other aspects do (Tsai, Chentsova-Dutton, & Wong, 2002). Nonetheless, it is not infrequent that one aspect of cultural orientation is used as a proxy for the whole concept. This is problematic, especially for Asian Americans, for whom, for example, the rate of heritage language retention is quite low, ranging from 1% to 10% among U.S.-born Asian youth subgroups (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001), which does not necessarily mean that they do not identify themselves as Asian Americans. Language use may not be linearly correlated with the level of acculturation either. Therefore, studies suggest that distinctions between domains of cultural orientation (such as ethnic pride versus language use or ethnic behaviors) are particularly significant among Asian American youth (Tsai, et al., 2002). It is also scientifically more refined to specify which aspects of cultural orientations are influenced by racial-ethnic variables and how they relate to youth outcomes. In this paper, we chose three aspects of cultural orientations for examination: language competence (English vs. Korean proficiency), behavioral participation in a culture (acculturation to the mainstream culture vs. enculturation of the heritage culture3), and identity (as American vs. as Korean). We selected these areas because they are most regularly used in the literature to assess cultural orientations and are particularly pertinent to Asian American youth.

Although some argue that the cultural adaptation process is orthogonal, where identification with any culture is essentially independent of identification with any other culture, an individual’s orientation to the mainstream culture would likely change the individual’s orientation to the culture of origin and vice versa (Choi, Kim, Pekelnicky, & Kim, 2012). For example, high endorsement of Western values such as independence would be negatively correlated with endorsement of traditional Asian values such as obedience. Thus, different dimensions of culture (i.e., mainstream orientation and ethnic orientation) are at least moderately and inversely correlated (H. H. Nguyen & von Eye, 2002).

Interplay of Racial-ethnic Socialization4 and Youth Cultural Orientations

The intention of cultural socialization is to increase children’s racial-ethnic identity and pride and children’s enculturation of heritage culture (Caughy, et al., 2002). Empirical data confirms that proactive cultural socialization in the family promotes children’s ethnic orientation including the retention of heritage language (Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001), racial-ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2013), and enculturation (Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009). Similar to cultural socialization, parental racial-ethnic identity increases children’s positive ethnic orientation (Smith, Atkins, & Connell, 2003). Parents who are concerned about their children’s minority status are also likely to encourage ethnic orientation in their children.5 A similar relationship is expected between parental experience of racial discrimination and cultural orientations, such that when parents and youth report racial discrimination, youth may report higher ethnic orientation.

However, it is less known how racial-ethnic socialization is related to mainstream orientation. It is expected that, although they are predominantly children of foreign-born immigrant parents, Asian American youth would speak primarily English, rapidly acculturate, and grow up American. In fact, the mismatch between children’s high level of mainstream orientation and parents’ relatively slow adoption of the mainstream culture is the main source of intergenerational conflict among Asian American families (Choi, He, & Harachi, 2008). However, establishing an identity as American may pose a challenge for Asian American youth. Society treats Whites as representative and unhyphenated Americans, in contrast to African or Asian Americans (C. J. Kim, 1999). Asian Americans are continually regarded as “forever foreigners,” and Asian American youth often report feeling like inauthentic Americans (Tuan, 1998). The literature on racial-ethnic socialization has yet to examine this threat to identity. In addition, existing studies have largely focused on ethnic orientation (Neblett, et al., 2012; Tran & Lee, 2010). In fact, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship between racial-ethnic socialization and dual cultural orientations. It is also less clear the difference racial-ethnic socialization would make in children’s English language proficiency and their level of acculturation, which may happen regardless of racial-ethnic socialization in the family. Although we lack sufficient information to generate specific hypotheses regarding these relationships, we speculate that racial-ethnic socialization may not have significant impact on mainstream orientation. One possible exception is youth who report experiences of racial discrimination. These youth may be less likely to see themselves as American and may acculturate less to the mainstream culture. Although this part of the investigation is exploratory, this study will be one of the first to explicitly examine the impact of racial-ethnic socialization on mainstream orientation.

Asian American Youth Outcomes

Contrary to the popular images of Asian American youth as relatively problem-free, the few existing studies of Asian American youth present a more nuanced and compelling story. It is true that Asian American high school youth as an aggregated group report better grades and lower rates of crimes, substance use, and risky sexual behaviors (Choi & Lahey, 2006; Jang, 2002). However, the rate of internalizing problems appears much worse among Asian American youth than among other youth. For example, depression is significantly higher among Asian American youth (Lipsicas & Mäkinen, 2010). Data from the Center for the Disease Control and Prevention also show that Asian Americans account for the highest suicides among all U.S. women aged 15–24, and the suicide rate among Asian American women is 2.5–3 times higher than that among White women (Shibusawa, 2008). This pattern of high internalizing and low externalizing problems applies to Korean American youth as well (Lee & Koeske, 2010). Youth problems usually co-occur with a shared etiology (Jaffee, Moffitt, Fombonne, Poulton, & Martin, 2002). Thus, the behavior pattern of Asian American youth, including Korean Americans, is uniquely distinctive. In this paper, we examine both externalizing and internalizing youth outcomes to ascertain whether racial-ethnic socialization and cultural orientation have similar or different impacts on youth outcomes, specifically depressive symptoms and antisocial behaviors.

Empirical findings on how racial-ethnic socialization and cultural orientations are related to youth developmental outcomes are mixed, with studies showing no effect, positive effects, or negative effects (Bynum, Burton, & Best, 2007; Caughy, et al., 2002; Marshall, 1995; Smith, et al., 2003; Tran & Lee, 2010). This is in part because different studies use different aspects of cultural orientations and racial-ethnic socialization to assess the entire constructs. Inconsistent findings in the literature further support the need to stipulate distinct aspects of race-ethnicity- and culture-related factors and to examine the aspects in relation to distinct youth outcomes in order to meaningfully advance our knowledge.

In addition, existing studies suggest that different race-ethnicity- and culture-related variables show distinct relationships with youth outcomes. For example, a strong sense of racial-ethnic identity is generally a protective factor for youth outcomes such as substance use and several delinquent behaviors, but not for physical fights (Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, & Catalano, 2006). In fact, a stronger sense of racial-ethnic identity increased physical fights among middle-school youth (Choi, et al., 2006). Ethnic orientation showed no effect or a moderately positive effect on youth outcomes, but mainstream orientation showed a significantly negative effect (Benner & Kim, 2009). Since language and behavioral acculturation are mostly inevitable, especially among children—accordingly, we expect that acculturation will have no significant impact on youth outcomes in this study—one’s identity as mainstream American may be primarily responsible for the negative effect. Scholars have argued that minority children who primarily identify themselves as mainstream Americans are likely to suffer more from negative experiences because they are less likely to be prepared to defend themselves and may feel betrayed by the group they felt they belonged to (Chae, Lee, Lincoln, & Ihara, 2012; Park, Schwartz, Lee, Kim, & Rodriguez, 2013). At the same time, construction of racial-ethnic identity and enculturation is often tenuous for youth who primarily rely on their parents for learning the culture (S. Y. Kim, Gonzales, Stroh, & Wang, 2006). However, this may mean that, because of the difficulty youth have in successfully establishing a strong racial-ethnic identity and high enculturation, those youth who are highly enculturated benefit greatly from this achievement. Accordingly, this study hypothesizes that identity as American would increase youth problems, whereas identity as Korean would decrease them.

The Present Study

This study focuses on early to middle adolescents between 11 and 14 years old. The developmental stages of early and middle adolescence provide an ideal time to examine the target constructs (Benner & Kim, 2009). Early adolescence is a period of particular interest as its beginning is marked by a biological event (the onset of puberty), and the process of identity development dominates this life phase (Archibald, Graber, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). During these stages, youth become more conscious of racial-ethnic issues and report an increase in discrimination (Brody et al., 2006). At the same time, the significance of parental active intervention in racial-ethnic socialization becomes more crucial as children reach middle-school age. For example, during early childhood, African American children tend to endorse Eurocentric racial attitudes, but those whose parents actively engage in racial-ethnic socialization develop Afrocentric racial attitudes starting at early to middle adolescence (Spencer, 1983). This is also a period when parents start becoming more explicit and proactive in the racial-ethnic socialization of their children. Parental experience of racial discrimination predicts preparing their children for racial bias if children are 10 years and older (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006).

Although studies have identified multiple roles of cultural orientations on youth outcomes (such as correlate or predictor, mediator, and moderator), scholarship during the last two decades has mostly focused on their role as a moderator, specifically on how factors such as racial-ethnic identity, enculturation, and retention of language buffer the effect of various risks, such as racial discrimination, stereotypes, intergenerational cultural conflicts with parents, and poverty (Downey, Eccles, & Chatman, 2005). The role of cultural orientations is rather complex and their role as a mediator on youth outcomes warrants attention. The current study expands the existing findings of cultural orientations by using multidimensional measures in discrete domains of cultural orientations and focusing on their mediating role via a path model in which racial-ethnic socialization affects cultural orientations among youth, which in turn affect youth developmental outcomes.

This study examines both concurrent and longitudinal impact of race-ethnicity and culture on youth development. Experience of racial-ethnic discrimination can have both contemporaneous and lasting effects (Benner & Kim, 2009). In a similar vein, racial-ethnic socialization and cultural orientations are likely to have both concurrent and enduring effects on youth outcomes. This paper examines both concurrent and longitudinal relationships by modeling racial-ethnicity- and culture-related variables to predict youth outcomes at the same time period and one year later. Early problem behaviors among youth are one of the strongest predictors of later problem behaviors (Bartusch, Lynam, Moffitt, & Silva, 1997; Moffitt, 1993). Similarly, significant evidence supports the developmental continuity of depression (Garber, Keiley, & Martin, 2002). Thus, to examine whether race-ethnicity- and culture-related variables predict youth outcomes above and beyond the prediction of prior behaviors, we add previous youth outcomes to the longitudinal model. Examining both concurrent and longitudinal impact of race-ethnicity- and culture-related variables is also important because these variables may have differential effects on varying types of youth behaviors. Specifically, experience of racial discrimination shows a significant concurrent effect on socioemotional outcomes but a lasting effect on academic achievement (Benner & Kim, 2009). Thus, it is possible to find varying effects of race-ethnicity and culture on depressive symptoms and antisocial behaviors. However, it is rare for studies on this topic to examine both contemporaneous and longitudinal analyses.

This study uses both parental and youth report of cultural socialization in the family. Parental report and youth report tend to differ on the same phenomenon (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). For example, parental report of family conflict (such as how often parent and youth had an argument) was not significantly correlated with youth report of family conflict, and in some cases, they were inversely correlated (Choi, et al., 2008). A similar pattern was found in their report of cultural socialization in the family (Hughes, Bachman, Ruble, & Fuligni, 2006). Thus, it is ideal to include both parental and youth report when available.

Method

Overview of the Project

Data are from the Korean American Families (KAF) project, a survey of Korean American youths and their parents living in a Midwest metropolitan area. There were two waves of the data collection. The first wave was collected in 2007 from 291 families (220 youths, 272 mothers, and 164 fathers, N = 656), and a follow-up survey was done a year later in 2008 (247 families; 220 youths, 239 mothers, and 146 fathers, N = 605). Korean American and immigrant families with early adolescents (ages between 11 and 14 years old) were eligible to participate. Participants were recruited from three sampling sources: phonebooks, public-school rosters, and Korean church or temple rosters. Approximately equal numbers of samples from each source participated, and further analyses revealed no statistical demographic differences across the three sources.

Sample Characteristics

At the first wave of data collection, the average ages were 12.97 years (SD=1.00) for youths, 43.4 years for mothers (SD=4.57), and 46.3 years for fathers (SD=4.69). Nearly 64% of mothers and 70% of fathers reported having attained some college education either in Korea or in the U.S. All parents were born in Korea and had lived in the U.S. for an average of 15.44 years (SD=8.36). Well over half (61%) of youth were U.S. born, and those who immigrated have lived in the U.S. for an average of 10.44 years (SD=4.14). About half (47%) of the families reported an annual household income between $50,000 and $99,999, followed by those between $25,000 and $49,999 (23.6%) and over $100,000 (22%). The remaining 7.4% made less than $25,000. Fifteen percent of mothers reported having received public assistance including food stamps or free/reduced-price school lunch. Approximately 40% of mothers reported being currently employed. Overall, the survey sample was predominantly urban, middle class, Protestant (76.7%), and small business owners (40%), which is fairly comparable to the Korean immigrant profile in the U.S. (Min, 2006) and representative data sets such as the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

Measures6

Parent Concerns about Race-Ethnic Status

We used four items to measure parental concerns about the potential disadvantages of being a racial-ethnic minority in a child’s positive development, social integration, and career development. These items were constructed on the basis of several focus groups with Korean American parents who expressed worries about their children’s racial-ethnic minority status as one of the primary obstacles in development (Choi & Kim, 2010). Items include “I worry that being an ethnic minority may hinder the positive development of my child” and “I worry that my child may have difficulty getting integrated into the mainstream society because s/he is Korean” (α=.80).

Parent Ethnic Identity and Pride

Eight items were adapted from the Language, Identity and Behavior scale (LIB, Birman & Trickett, 2002). Similar to the concept of high private regard (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998), items asses ethnic identity, a sense of belonging to the Korean culture, and ethnic pride. Examples include “I think of myself as being Korean” and “I feel good about being Korean” (α=.88).

Parent Perceived Racial Discrimination

Developed by Phinney, Madden, and Santos (1998), this eight-item scale measures perceptions by others on one’s own group, similar to the notion of low public regard by Sellers and his colleagues (1998). In addition, the scale asks whether respondents have experienced discrimination due to their race-ethnicity, such as not getting services or being looked down on. We revised the items to specify the target ethnic group. An example item was “You do not feel accepted by other Americans” (α=.81).

Youth Perceived Racial Discrimination

Parallel to the parent items (Phinney, et al., 1998), but revised for youth, this eight-item scale asked youth participants how they think others perceive their ethnic group and the frequency of being treated unfairly by students and teachers in school (α=.79).

Parent Report Cultural Socialization

Eight questions asked about the frequency of parental daily activities practiced to enculturate their children to their culture of origin. We drew the activities from the focus groups with Korean American parents (Choi & Kim, 2010). Examples of this index scale include “I talk about cultural values with my child” and “I send my child to the Korean schools.” The response options were either 0 (No) or 1 (Yes).

Youth Report Cultural Socialization

We created these 10 items from the focus groups with Korean American youth about what their parents do to transmit Korean culture in the family (Choi & Kim, 2010). Each item began with “How much do your parents emphasize to you…” followed by a cultural practice, such as, “Speaking Korean” and “Keeping Korean traditional manners and etiquettes” (α=.83).

Youths’ Cultural Orientation Mediators

Language competency: Korean and English

Adopted from the LIB (Birman & Trickett, 2002), two sets of 4 parallel items (8 total) measure youths’ language competency in Korean and English respectively. The questions include “How would you rate your overall ability to speak Korean (or English)?” and “How well do you understand Korean (or English)?” (α=.86 for Korean and α=.91 for English).

Cultural Participation: Acculturation and enculturation

Adopted from LIB (Birman & Trickett, 2002), a total of 18 items measure youths’ participation in either Korean or American cultural activities. Question topics include peer composition, participation in social clubs or parties, media use, and food, for example, “How often do you usually listen to Korean (or American) songs?” (α=.76 for enculturation and α=.77 for acculturation).

Ethnic identity: Korean and American Identity

Similar to the language scales, a total of 14 questions from LIB (Birman & Trickett, 2002) ask the extent to which youth identify themselves either as Korean or as Americans, for example, “I think of myself as being Korean (or American)” and “I have a strong sense of being Korean (or American)” (α=.88 for Korean identity and α=.91 for American identity).

Youths Outcomes7

Depressive symptoms

Fourteen items from the Children’s Depression Inventory (Angold, Costello, Messer, & Pickles, 1995) and the Seattle Personality Questionnaire for Children (Kusche, Greenberg, & Beilke, 1988) assess the frequency of depressive symptoms during the two weeks prior to the survey, for example, “I found it hard to think properly or concentrate,” “I felt miserable or unhappy,” and “I feel like crying a lot of the time” (α=.91 in both waves).

Antisocial behaviors

We adopted 34 items from the DSM criteria for conduct disorder as well as several measures of antisocial behaviors frequently used in research, such as the Seattle Social Development Project (Hawkins & Catalano, 1990) and the Seattle Personality Questionnaires (Kusche, Greenberg, & Beilke, 1988), including measures of delinquent and aggressive behaviors. As only a few youth reported committing a behavior frequently, we dichotomized each item so that responses were either 0 for no incidence of the behavior or 1 for any incidence of the behavior, and we summed answers for the items (range from 0 to 34) (α=.83 in Wave 1 and α=.90 in Wave 2). Because a high rate of the respondents reported having no antisocial behaviors, we further dichotomized the scale into binary variable, 0 for no and 1 for any antisocial behaviors.

Demographic Controls

We included a few demographic characteristics in the analysis, specifically age and gender of the child and parent report of family socioeconomic status (SES), to account for their impact on youth outcomes. Family SES was coded 1 (Yes) if they have received public assistance and 0 (No) if they had not. The gender variable was coded 1 (boys) and 0 (girls).

Analysis Plan

We constructed the data around youth participants (n=296), which we matched to their parents’ data. If both parents for a child participated, we used the mean of parents’ responses for parent constructs. Before testing the conceptual model, we conducted several univariate and bivariate descriptive analyses including means, standard deviations, and variance at the individual item and construct levels, item-total correlations and reliability of each construct, and pairwise correlations among constructs. We examined descriptive statistics across gender groups as well as with a combined group and across both waves whenever available.

We used path analysis within a structural equation modeling framework to test relations in the model. Path analysis enables a simultaneous investigation of direct and indirect effects of the model. In addition, to test both concurrent and predictive relationships between racial-ethnic socialization, mediating cultural orientations, and youth outcomes, we used youth behavior from both Wave 1 and Wave 2. We first ran a model with independent and mediating variables at Wave 1, predicting youth outcomes at Wave 1 to examine concurrent relationships. We executed the same process with independent and mediating variables at Wave 1, predicting youth outcomes at Wave 2 to examine predictive relationships over a one-year time frame. To examine whether racial-ethnic socialization and cultural orientation variables predict youth outcomes above and beyond the prediction of prior behaviors, we added youth outcomes at Wave 1 as one of the independent variables in longitudinal model. We used M Plus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013) to examine the path models.

We assessed the fit of all models by examining model chi-square (χ2), the Comparative Fit Indices (CFI, Bentler, 1990), and the Root Mean Squared Error Approximation (RMSEA, Browne & Cudeck, 1993). A good fit is indicated by CFI values of greater than 0.90 (Byrne, 1994). Values of less than 0.05 for the RMSEA are considered evidence of a good fit, values between 0.05 and 0.08 indicate a fair fit, and values greater than 0.10 represent a poor fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). We examined the statistical significance of the estimated parameters with z statistics and a 0.05 level of statistical significance. We also used Modification Indices (MI) function to investigate whether data suggest adding or dropping any particular path in the model. We made path modifications only when they had conceptual justifications. We used Maximum Likelihood (ML) for estimating the models and handling missing data, because the outcome variables include both continuous (depressive symptoms) and binary (antisocial behaviors). The rate of missing data was low (less than 5%) in the data set.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics of the study constructs. Notable findings are that, as suggested in the literature, Korean American parents reported a fairly high level of ethnic identity and pride. However, both parents and youth reported a modest level of perceived racial discrimination. Both parental report (.81 out of 0 to 1 scale) and youth report (4.14 out of 5 scale) of cultural socialization was very high. Youth reported higher English language competence as expected but much higher Korean ethnic identity than American identity. Bivariate correlations present in general the expected patterns—parent report and youth reports of cultural socialization were not correlated; some racial-ethnic socialization variables were positively correlated with each other; and mainstream orientation variables and ethnic orientation variables were inversely but modestly correlated with one another. One unexpected finding was that parental report of cultural socialization was positively and significantly correlated with youth English proficiency. Depressive symptoms and antisocial behaviors were positively correlated and sometimes across time points. We tested their specific interrelations in the following path models.

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviations and correlations of the study constructs

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parental concerns | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | Parent Ethnic Identity | 0.13* | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | Parent Racial Discrimination | 0.35*** | 0.05 | -- | |||||||||||||

| 4 | Youth Racial Discrimination | 0.14* | 0.07 | 0.14* | -- | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Parent Culture Socialization | 0.06 | 0.19*** | 0.07 | −0.07 | -- | |||||||||||

| 6 | Youth Culture Socialization | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.12 | -- | ||||||||||

| 7 | Korean Competency | 0.12 | 0.17* | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.09 | -- | |||||||||

| 8 | English Competency | −0.03 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16* | 0.10 | −0.34*** | -- | ||||||||

| 9 | Korean Identity | −0.02 | 0.10 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.37*** | 0.17* | 0.11 | -- | |||||||

| 10 | American Identity | −0.08 | −0.25*** | −0.11 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.06 | −0.37*** | 0.44*** | 0.01 | -- | ||||||

| 11 | Enculturation | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.15* | 0.40*** | 0.47*** | −0.16* | 0.38*** | −0.19** | -- | |||||

| 12 | Acculturation | −0.04 | −0.24 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.12 | −0.38*** | 0.52*** | −0.13 | 0.57*** | −0.25*** | -- | ||||

| 13 | Depressive Symptoms (W1) | −0.01 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.27*** | −0.09 | −0.13 | 0.17* | −0.08 | −0.18** | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.19** | -- | |||

| 14 | Depressive Symptoms (W2) | −0.05 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.23** | −0.02 | 0.14 | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.36*** | -- | ||

| 15 | Antisocial Behaviors (W1) | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.01 | −0.05* | 0.01 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.07 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.24*** | 0.18* | -- | |

| 16 | Antisocial Behaviors (W2) | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.20** | 0.29*** | -- |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Mean | 1.96 | 3.99 | 1.47 | 1.75 | 0.81 | 4.13 | 3.12 | 4.47 | 4.37 | 3.35 | 3.51 | 3.81 | 1.55 | 1.72 | 0.78 | 0.68 | |

| Standard Deviations | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.37 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 0.47 | |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Initial path models

Before moving forward to testing the entire conceptual model, we first examined the relationships between racial-ethnic socialization and mediating cultural orientation variables to come up with a more parsimonious model. There are 36 possible paths between racial-ethnic socialization constructs and cultural orientation constructs in the model. Although it is more rigorous to use as many multiple measures as possible to tease out complex concepts such as the study constructs, the model would have been under-identified—the study sample would have been too small to run the entire model at once. Nonetheless, this approach, compared to an alternative in which we combine all scales to create a one-dimensional super construct, enables us to partition out more or less salient aspects of racial-ethnic socialization that influence youth cultural orientations and ultimately youth outcomes. Based on bivariate and path analyses, we dropped three constructs (parental concerns about racial-ethnic status and both parent and youth perceived racial discrimination) from the model that were not significantly associated with any of the mediating variables regardless of gender of youths or parents. Path analyses also confirmed the same patterns. More details of this part of the analyses are available from the authors.

Final path models

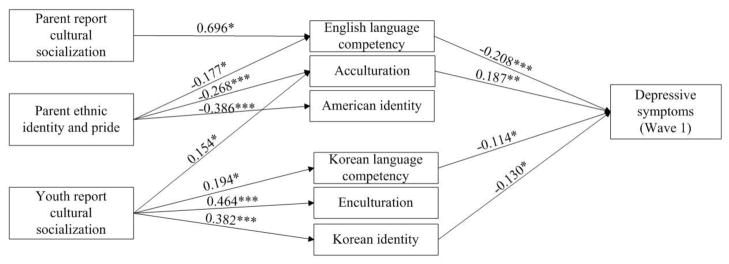

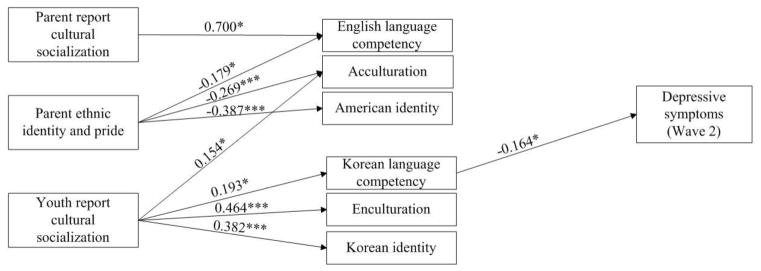

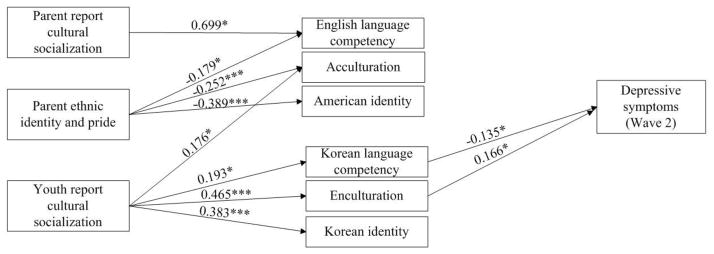

Figures 2, 3, and 4 show the results from the three path models, in the order of concurrent, longitudinal models and longitudinal model accounting for prior youth outcomes. In the final path models presented, antisocial behavior outcome was excluded because the overall model, especially youth cultural orientation variables, did not significantly explain antisocial behaviors. All final models with depressive symptoms as an only outcome variable fit the data well. Fit indices were χ2(27) = 56.61, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06 for the concurrent model (R2=21%). For the longitudinal model, the fit was χ2(27) = 59.76, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06 (R2=9%). Lastly, in the longitudinal model accounting for prior youth outcomes, the fit was χ2(35) = 78.32, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06 (R2=22%).

Figure 2.

Final concurrent path model (Wave 1 outcomes)

Fit indices: χ2(27) = 56.614, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.930, RMSEA = 0.061

Path coefficients are standardized, *p < .05; ** p< .01; ***p < .001

Several paths are not shown for simplicity, e.g. three controls for the outcome variable (age, gender, and family SES) and covariations, respectively, among three independent variables on the far left hand side, three ethnic orientation variables and three mainstream orientation variables. Also not shown are three additional paths between ethnic orientation and mainstream orientation variables, suggested by Modification Index (MI).

Figure 3.

Final longitudinal path model (Wave 2 outcomes)

Fit indices: χ2(27) = 59.759, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.919, RMSEA = 0.064

Path coefficients are standardized, *p < .05; ** p< .01; ***p < .001

Several paths are not shown for simplicity, e.g. three controls for the outcome variable (age, gender, and family SES) and covariations, respectively, among three independent variables on the far left hand side, three ethnic orientation variables and three mainstream orientation variables. Also not shown are three additional paths between ethnic orientation and mainstream orientation variables, suggested by Modification Index (MI).

Figure 4.

Final longitudinal path model (Wave 2 outcomes, controlling for Wave 1 outcomes)

Fit indices: χ2(35) = 78.320, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.904, RMSEA = 0.065

Path coefficients are standardized, *p < .05; ** p< .01; ***p < .001

Several paths are not shown for simplicity, e.g. four controls for the outcome variable (age, gender, family SES, and prior level depressive symptoms) and covariations, respectively, among three independent variables on the far left hand side, three ethnic orientation variables and three mainstream orientation variables. Also not shown are three additional paths between ethnic orientation and mainstream orientation variables, suggested by Modification Index (MI).

The coefficients, directions, and statistical significance of pathways between racial-ethnic socialization and mediating acculturation variables were similar across the three models. Results showed that parent report of cultural socialization practices was positively associated with youth English competency. This was an unexpected finding. Parental ethnic identity and pride were significantly and negatively associated with youth mainstream orientation, specifically English proficiency, acculturation, and identity as American, but were not significantly associated with youth ethnic orientation. Conversely, youth report of cultural socialization in the family was positively associated with all three ethnic orientation variables, but also unexpectedly with acculturation.

Across the models, there was a notable pattern of relations between cultural orientation variables and youth outcomes: Korean proficiency negatively predicted depressive symptoms concurrently, longitudinally, and even after accounting for prior depressive symptoms. We found three additional paths to be significant in the concurrent model, in which English proficiency and Korean identity were negatively associated with depressive symptoms, whereas acculturation was positively associated with depressive symptoms. These three paths were not found to be significant in the longitudinal model. After accounting for the level of prior depressive symptoms, enculturation was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms a year later.

We found the following indirect effects on depressive symptoms in the concurrent model: parental ethnic identity and pride via youth acculturation (β=−0.051, p < .05) and parent report cultural socialization via English proficiency (β=−0.146, p < .05). Youth-reported cultural socialization showed an indirect effect on depressive symptoms a year later via enculturation (β=0.077, p < .10). These findings showed that many racial-ethnic socialization variables were significantly associated with their immediate dependent variables (their mediating cultural orientation variables), but they did not directly explain the variance in the outcome variables.

Finally, MIs suggested adding three pathways among mediators. They seem to make conceptual sense: aspects of mainstream and ethnic orientations are expected to be inversely associated, although not too strongly. Specifically, acculturation negatively predicted Korean language competence and enculturation and American identity also negatively predicted Korean language competence. Coefficients of the suggested paths ranged from −.184 to −.348. We added the three paths, and the reported model fits improved after the addition. The model fit indices we reported earlier are after adding these paths.

Discussion

This study examined the interplay of parental racial-ethnic socialization and youth cultural orientations to investigate how they indirectly and directly influence youth developmental outcomes, depressive symptoms, and antisocial behaviors. The overall pattern of the findings is that racial-ethnic socialization—cultural socialization and parental racial-ethnic identity and pride—is significantly associated with mainstream and ethnic cultural orientation among youth, which in turn influenced depressive symptoms among Korean American early adolescents. More specifically, the main findings indicate that parental racial-ethnic identity and pride discourage youth mainstream orientation, whereas cultural socialization in the family, as perceived by youth, increases ethnic orientation. These findings suggest a varying impact of racial-ethnic socialization on the multidimensional cultural orientations of youth. Korean proficiency of youth was most notably predictive of a decrease in the number of depressive symptoms concurrently and longitudinally and after controlling for the previous level of depressive symptoms.

We examined cultural adaptation as a dual process of both mainstream orientation and ethnic orientation, and the findings are mixed with mostly expected but a couple of unexpected findings. The study hypothesized that mainstream orientation may not have a significant impact on youth outcomes, but the results showed that English proficiency was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, whereas acculturation was associated with more symptoms. These results may suggest that English proficiency is necessary to defend against depressive symptoms because of the necessity of English language knowledge to navigate comfortably and successfully through daily life, whereas greater acculturation may create unease in individuals who are embracing a culture that carries negative perceptions of their race-ethnicity. However, mainstream orientation seemed to primarily influence depressive symptoms indirectly by reducing Korean language proficiency, which we found to be beneficial for youth.

It is intriguing to see the beneficial impact of both Korean and English proficiency in the concurrent model. This finding may suggest a benefit of bilingualism, which is conceptualized as being competent in two languages and is thought to be beneficial to youth development (LaFromboise, et al., 1993). The concept of bilingualism is closely tied to that of biculturalism. Previous studies suggest that bilingualism and biculturalism each provide a variety of benefits and that the benefits of each appear to intensify the benefits of the other. For example, bilingualism leads to improved academic performance among Asian American students (S. K. Lee, 2002; Liu, Benner, Lau, & Kim, 2009) and improves family relations (Boutakidis, Chao, & Rodriguez, 2011). Among Korean-American college students, bilingualism leads to improved acculturation to the mainstream culture and to increased success in balancing both the heritage and mainstream cultures (J. S. Lee, 2002). Finally, meta-analysis of 83 studies showed a clear relationship between biculturalism and adjustment (A.-M. D. Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013).

Actually, the process of cultural adaptation, especially among children and youth, may lead to a hybrid orientation rather than to two distinct orientations. A couple of recent studies show the importance of considering a hybrid orientation, which is not simply the sum of its component (such as American vs. Asian) but a unique cultural orientation that represents the experience of living in the U.S. as a racial-ethnic minority (such as Asian American) (Choi, et al., 2012; S. Y. Kim, et al., 2006). Although it is important to examine the multidimensional nature of the cultural adaptation process as we did in this paper, it is equally critical to consider a new hybrid orientation that may resemble the concept of biculturalism that scholars have advocated in recent years. As a next step, research should examine distinct latent types of cultural adaptation, for example, similar to John Berry’s four types of adaptation (1997)—integration (high on both mainstream and ethnic orientation), assimilation (high only on mainstream orientation), separation (high only on ethnic orientation), and marginalization (low on both orientations). This integrative approach, in contrast to the dual and separate process approach taken in this paper, would enable the test of biculturalism and its benefit in youth development. Nonetheless, the current study extends current knowledge by investigating whether each component of mainstream orientation and ethnic orientation uniquely contributes to different kinds of youth developmental outcomes.

Although we did not include them in the conceptual model, we found some interesting relationships in the bivariate correlations. Youth perceived racial discrimination was positively correlated with depressive symptoms the same year the discrimination was experienced and a year later, consistent with existing studies that have documented a detrimental effect of racial discrimination on youth mental health (e.g., Benner & Kim, 2009; Huynh & Fuligni, 2010). If we had modeled direct paths between youth experience of racial discrimination and depressive symptoms both concurrently and longitudinally, we might have seen significant relations. Youth report of cultural socialization also showed a significant and negative correlation with antisocial behaviors. Delgado and her colleagues (2011) found that cultural factors protected Mexican-origin adolescents from the negative impact of discrimination in relation to externalizing behaviors, but not in relation to internalizing symptoms, which may be more difficult to minimize than externalizing behaviors or may be minimized via a different set of cultural factors. Although we did not include this relationship in the final path models of our study, future investigation is warranted into the potential benefit of cultural socialization in reducing antisocial behaviors. In fact, the final conceptual model did not explain antisocial behaviors well. Although the poor fit of the model with this outcome may be due to the limited range of the variable in the dataset used, this may be another indication that there are other aspects of cultural socialization and cultural orientations not included in this study that influence antisocial behaviors.

There are several caveats to consider in interpreting the findings. First, as Caughy and her colleagues (2002) pointed out, parental racial-ethnic socialization is likely confounded with general parenting practices and parental attitudes. Specifically, parents who are more involved in general may engage in racial-ethnic socialization more actively, and thus parental involvement, not racial-ethnic socialization, may predict children’s ethnic orientation (Caughy, et al., 2002).

Although this paper examined a conceptual relationship directing from racial-ethnic socialization to youth cultural orientations, other studies have examined a relationship with the directionality between concepts reversed (e.g., Hughes & Johnson, 2001). Hughes and Johnson’s study found that parents communicate more frequently about racial-ethnic bias if their children report experiencing discrimination, especially by adults. In addition, youth information seeking about their racial-ethnic history had some influence on parental racial-ethnic socialization. Nonetheless, they found that parents play a central role in determining racial-ethnic socialization, which is in line with the conceptual model of the current study. This is not to say that there is only one right direction. The relations between racial-ethnic socialization and youth cultural orientations are likely to be recursive and transactional (Hughes & Johnson, 2001; S. Y. Kim, et al., 2006). Parents are likely to revise parenting practices and behaviors in response to children’s needs. In fact, our finding that cultural socialization may strengthen aspects of mainstream orientation may suggest this recursive directionality. Specifically, parent report of cultural socialization was associated with increased English proficiency. Youth report of cultural socialization was also associated with increased youth acculturation. This may be an indication that cultural socialization in the family and youth mainstream orientation is interactive, and that cultural socialization increases in response to youth’s higher English proficiency and acculturation. This study is one attempt to parcel out the intricate relationships among the target constructs with a special focus on understanding how parents play a role in the critical process of developing cultural orientations. However, future study should model recursive and transactional relationships among the target constructs, using longitudinal data with multiple time points.

Parental SES and children’s age are likely significant factors of racial-ethnic socialization. For example, parents with higher income and education tend to practice cultural socialization more frequently than their counterparts (Caughy et al., 2002). We earlier discussed the role of child age in racial-ethnic socialization. In this paper, we included youth age in the model only to account for youth developmental outcomes but not racial-ethnic socialization. The age range of the sample was limited to early to middle school years, which limited variability in how parents may adopt racial-ethnic socialization depending on child’s age. Similarly, despite some variation in parental SES, the characteristics of this study sample are relatively homogeneous, compared to the national population data. Thus, accounting for parental SES and youth age only for youth outcomes seems sensible in this study.

In addition, some of the racial-ethnic socialization variables may be correlates to one another—for example, parental experience of racial discrimination or their own sense of identity are likely be predictors of cultural socialization (Hughes & Johnson, 2001). However, we constructed the conceptual model with a focus on testing the mediating role of youth cultural orientations and how they are predicted by parental racial-ethnic socialization. Given that the data provided only two time points, it seemed reasonable to not model too many mediating pathways. In addition, we left out other factors that are less salient to this specific sample but are part of racial-ethnic socialization. For example, neighborhoods and regions of residence, varying in racial-ethnic compositions, determine experience of race-ethnicity. The sample we used is mainly from the Midwest and predominantly living in suburbs, so we did not include a neighborhood factor in the model.

Finally, the conceptual model in this paper was tested through an investigation of the interplay of race-ethnic- and culture-related variables in the family and how they influence youth outcomes, rather than by strictly testing the model for verification, which led to a combination of mostly expected but a few unexpected results. Given the lack of empirical data to support the current theories of the impact of racial-ethnic socialization and cultural orientations on youth developmental outcomes, the results from this study should be viewed as an exploration providing directions for future research. For example, as mentioned earlier, some temporal sequences were suggested by the data, i.e. parental ethnic identity and pride reduced mainstream orientation, which was inversely associated with ethnic orientation and indirectly influenced youth behaviors. Since both mainstream and ethnic orientation variables were measured at the same time point in this dataset, these possible temporal relationships should be tested with longitudinal data to empirically and theoretically validate such complex relations. The results of this study also show that parent race-ethnic and culture variables are mainly associated with mainstream orientation variables among youth while youth report cultural socialization is significantly related with ethnic orientation variables. We are not aware of any specific theory that stipulates differential impact of parent versus youth variables on cultural orientations and this study finding warrants additional investigation.

In the aftermath of the acquittal verdict of George Zimmerman for killing African American teenager Trayvon Martin in Florida, the media widely discussed whether and how the event would alter the parenting practices and behaviors of parents of African American teenagers. For example, would parents tell their children not to wear a hooded sweatshirt, which Zimmerman used as one of his excuses to judge Martin as a delinquent and a serious threat to his life, thereby justifying his killing as self-defense? Parents of color face these types of challenges daily to help their children deal with the racist mainstream society, ranging from microaggressions including racial-ethnic harassments at school to social and judicial inequality in the larger context as epitomized by Trayvon Martin’s case. Asian American youth suffer from racially-ethnically motivated bullying at school more than any other racial-ethnic group and have to deal with a range of racial-ethnic discrimination. Yet, there is limited attention to understanding the impact of discrimination on Asian American youth, and further, how parents can prepare Asian American youth in the face of the risks associated with growing up as a racial-ethnic minority. This study is a step toward developing the much-needed empirical literature on racial-ethnic socialization among Asian American youth.

Recent studies have shown a protective role of retaining heritage culture and language among children of immigrants as well as the value of a positive and strong racial-ethnic identity to grow healthy in this society as a racial-ethnic minority. However, less is known about how to promote them among youth (Hughes, Rodriguez, et al., 2006). This study is one of the few that attempts to shed light on the matter and guide parents of color on how to help and protect their children. Based on the findings, preventive interventions can be designed to focus on strengthening parental racial-ethnic identity and pride and increasing cultural socialization in the family with a goal of fortifying ethnic orientation of youth, especially youth’s heritage language competence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. K01 MH069910), Seed Grants from the Center for Health Administration Studies, and a Junior Faculty Research Fund from the School of Social Service Administration and the Office of Vice President of Research and Argonne Laboratory at the University of Chicago to the first author.

Footnotes

Race and ethnicity (similarly, racial socialization and ethnic socialization or racial identity and ethnic identity) are often used interchangeably, yet there is no clear solution for conceptually and empirically distinguishing the terms (Hughes et al., 2006). In this paper, we use the combined term, race-ethnicity (or racial-ethnic as a modifier) because the constructs of the study include the issues related to both race and ethnicity.

See Hughes and her colleagues (2006) for the definition and extensive review of each component.

While both acculturation and enculturation relate to learning a culture and adopting its practices and values, in the current literature, acculturation commonly refers to learning the mainstream culture and adopting its practices and values and the term enculturation is often used to indicate the degrees to which children of immigrants or cultural minorities maintain or learn their heritage culture.

Racial-ethnic socialization in the rest of this paper consists of cultural socialization as well as several contextual influences of racial-ethnic socialization, specifically, parent’s concern about race/ethnic status, parent’s racial-ethnic identity and pride, and racial discrimination experienced by youth and parents.

Or conversely, as shown among Japanese Americans, parents may encourage their children to assimilate to the mainstream culture as soon as possible. Such a trend was prevalent in the early years of immigration among Asian Americans. However, a recent trend is toward the promotion of ethnic orientation in response to the perceived vulnerability as a minority.

Unless noted otherwise, response options for all measures were ordinal Likert scale, ranging from 1 (e.g., rarely or not at all) to 5 (e.g., very often or strongly). Some of the scales were adopted from existing studies and have been tested for the instrument validity (for example, the Language, Identity and Behavior (LIB) scale and youth outcome scales). Other relatively newer scales (e.g. parent concerns about race-ethnic status and cultural socializations) were examined for validity, although details are not reported in this paper. As reported here, they show a high reliability (>.80), except parental report of cultural socialization, an index scale, does not require a high internal consistency as a scale.

The study used two youth outcomes (depressive symptoms and antisocial behaviors) measured at two time points.

References

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5(4):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald AB, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J. Pubertal processes and physiological growth in adolescence. In: Adams G, Berzonsky M, editors. Blackwell Handbook on Adolescence. Cornwall, UK: Blackwell; 2006. pp. 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bartusch DRJ, Lynam DR, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Is age important? Testing a general versus a developmental theory of antisocial behavior. Criminology. 1997;35(1):13–48. [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Kim SY. Experiences of discrimination among Chinese American adolescents and the consequences for socioemotional and academic development. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(6):1682–1694. doi: 10.1037/a0016119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Fit indexes, Lagrange multipliers, constraint changes and incomplete data in structural models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25(2):163–172. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: International Review. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett EJ. Psychology. University of Illinois, Chicago; Chicago: 2002. The “language, identity, and behavior” (LIB) acculturation measure. [Google Scholar]

- Boutakidis IP, Chao RK, Rodriguez JL. The Role of Adolescents’ Native Language Fluency on Quality of Communication and Respect for Parents in Chinese and Korean Immigrant Families. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2011;2(2):128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Murry VM, Ge X, Simmons RL, Gibbons FX. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CM, Ling W. Ethnic-racial socialization has an indirect effect on self-esteem for Asian American emerging adults. Psychology. 2012;3(1):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum MS, Burton ET, Best C. Racism experiences and psychological functioning in African American college freshmen: Is racial socialization a buffer? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(1):64–71. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MO, O’Campo PJ, Randolph SMNK. The influence of racial socialization practices on the cognitive and behavioral competence of African American preschoolers. Child Development. 2002;73(5):1611–1625. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae D, Lee S, Lincoln K, Ihara E. Discrimination, Family Relationships, and Major Depression Among Asian Americans. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012;14:361–370. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9548-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Harachi TW, Gillmore MR, Catalano RF. Are multiracial adolescents at greater risk? Comparisons of rates, patterns, and correlates of substance use and violence between monoracial and multiracial adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(1):86–97. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, He M, Harachi TW. Intergenerational cultural dissonance, family conflict, parent-child bonding, and youth antisocial behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS. Acculturation and enculturation: Core vs. peripheral changes in the family socialization among Korean Americans. Korean Journal of Studies of Koreans Abroad. 2010;21:135–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS, Pekelnicky DD, Kim HJ. Preservation and Modification of Culture in Family Socialization: Development of Parenting Measures for Korean Immigrant Families. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028772. available on-line. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Lahey BB. Testing model minority stereotype: Youth behaviors across racial and ethnic groups. Social Service Review. 2006;80(3):419–452. doi: 10.1086/505288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Copeland W, Angold A. Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: What changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(10):1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE., Jr Tracing the historical origins of youth delinquency and violence: Myths and realities about Black culture. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59(1):67–82. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant Discrepancies in the Assessment of Childhood Psychopathology: A Critical Review, Theoretical Framework, and Recommendations for Further Study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(4):483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Updegraff KA, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Discrimination and Mexican-Origin Adolescents’ Adjustment: The Moderating Roles of Adolescents’, Mothers’, and Fathers’ Cultural Orientations and Values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Kim SY, Vaughan PW, Li J. Cultural Orientation as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Chinese American Adolescents’ Discrimination Experiences and Delinquent Behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1027–1040. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9460-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Eccles JS, Chatman CM, editors. Navigating the future: Social identity, coping, and life tasks. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Evans AB, Banerjee M, Meyer R, Aldana A, Foust M, Rowley S. Racial Socialization as a Mechanism for Positive Development Among African American Youth. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(3):251–257. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Keiley MK, Martin NC. Developmental trajectories of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Predictors of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):79–95. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Garcia HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. Assimilation in American life: the role of race, religion and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(1–2):15–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Bachman MA, Ruble DN, Fuligni A. Tuned in or tuned out: Parents’ and children’s interpretation of parental racial/ethnic socialization practices. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda CS, editors. Child Psychology: A Handbook of Contemporary Issues. 2. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2006. pp. 591–610. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Johnson D. Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(4):981–995. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(5):747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh VW, Fuligni AJ. Discrimination Hurts: The Academic, Psychological, and Physical Well-Being of Adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20(4):916–941. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Fombonne E, Poulton R, Martin J. Differences in early childhood risk factors for juvenile-onset and adult-onset depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(3):215–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SJ. Race, ethnicity, and deviance: A study of Asian and non-Asian adolescents in America. Sociological Forum. 2002;17(4):647–680. [Google Scholar]

- Kim CJ. The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society. 1999;27(1):105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Gonzales NA, Stroh K, Wang JJ. Parent-Child cultural marginalization and depressive symptoms in Asian American family members. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34(2):167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kusche CA, Greenberg MT, Beilke R. Seattle Personality Questionnaire for Young School-Aged Children. Department of Psychology. University of Washington; Seattle: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Coleman H, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(3):395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde RN, Jones JM, Stroink ML. Racial identity, racial attitudes, and race socialization among Black Canadian parents. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2008;40(3):129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Koeske GF. Direct and Moderating Effects of Ethnic Identity. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development. 2010;20(2):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS. The Korean Language in America: The Role of Cultural Identity in Heritage Language Learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum. 2002;15(2):117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK. The Significance of Language and Cultural Education on Secondary Achievement: A Survey of Chinese-American and Korean-American Students. Bilingual Research Journal. 2002;26(2):327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsicas CB, Mäkinen IH. Immigration and suicidality in the young. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;55(5):247–281. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LL, Benner AD, Lau AS, Kim S. Mother-Adolescent Language Proficiency and Adolescent Academic and Emotional Adjustment Among Chinese American Families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38 doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9358-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S. Ethnic socialization of African American children: Implications for parenting, identity development, and academic achievement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24(4):377–396. [Google Scholar]

- Min PG. Preserving ethnicity through religion in America: Korean protestants and Indian Hindus across generations. New York: New York University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100(4):674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata D, Cheng WJY. Intergenerational communication of race-related trauma by Japanese American former internees. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2003;73:266–278. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.73.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The Promise of Racial and Ethnic Protective Factors in Promoting Ethnic Minority Youth Development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(3):295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AMD, Benet-Martínez V. Biculturalism and Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2013;44(1):122–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, von Eye A. The acculturation scale for Vietnamese adolescents (ASVA): A bimidemsional perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26(3):202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Park IJK, Schwartz SJ, Lee RM, Kim M, Rodriguez L. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and antisocial behaviors among Asian American college students: Testing the moderating roles of ethnic and American identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19(2):166–176. doi: 10.1037/a0028640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero AA, Williams LM. Racial and ethnic stereotypes and bullying victimization. Youth & Society. 2011:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF. Parenting in Black families with young children: A historical perspective. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black families. Vol. 2. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JE, Rudman LA. Reactions to ethnic deviance: The role of backlash in racial stereotype maintenance. [doi:10.1037/a0018304 DO - 10.1037/a0018304] Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99(2):265–281. doi: 10.1037/a0018304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Madden T, Santos LJ. Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28(11):937–953. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Romero I, Nava M, Huang D. The Role of Language, Parents, and Peers in Ethnic Identity Among Adolescents in Immigrant Families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30(2):135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG, editors. Legacies: the story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley, New York: University of California Press & Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]