Abstract

Exposure to a blast wave has been proposed to cause mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), with symptoms including altered cognition, memory, and behavior. This idea, however, remains controversial, and the mechanisms of blast-induced brain injury remain unknown. To begin to resolve these questions, we constructed a simple compressed air shock tube, placed rats inside the tube, and exposed them to a highly reproducible and controlled blast wave. Consistent with the generation of a mild injury, 2 weeks after exposure to the blast, we found that motor performance was unaffected, and a panel of common injury markers showed little or no significant changes in expression in the cortex, corpus callosum, or hippocampus. Similarly, we were unable to detect elevated spectrin breakdown products in brains collected from blast-exposed rats. Using an object recognition task, however, we found that rats exposed to a blast wave spent significantly less time exploring a novel object when compared with control rats. Intriguingly, we also observed a significant shortening of the axon initial segment (AIS) in both the cortex and hippocampus of blast-exposed rats, suggesting altered neuronal excitability after exposure to a blast. A computational model showed that shortening the AIS increased both threshold and the interspike interval of repetitively firing neurons. These results support the conclusion that exposure to a single blast wave can lead to mTBI with accompanying cognitive impairment and subcellular changes in the molecular organization of neurons.

Key words: axon initial segment, ion channel, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

The detonation of explosives creates a blast wave characterized by rapid changes in air pressure. In recent military conflicts, improved body armor has reduced penetrating and blunt impact injuries caused by the blast.1,2 Clinical data, however, suggest the brain may be susceptible to injury by the blast wave itself, even in the absence of external injuries, although this conclusion remains controversial.3–10 Sustaining a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) can lead to the development of cognitive, emotional, or behavioral symptoms, collectively known as post-concussive syndrome.11,12 Although most patients fully recover in a few weeks, the symptoms may persist in some.13 The increased survival rates of soldiers exposed to explosions, combined with an increase in the number of soldiers reporting cognitive, emotional, or behavioral symptoms after blast exposure,14,15 prompted us to reevaluate if blast waves themselves cause mTBI. Major challenges associated with this question, however, include the lack of human pathology in blast-induced mTBI, crude animal models, and the lack of specific molecular mechanisms contributing to blast-induced mTBI.

Nervous system injury can disrupt function through many mechanisms, including axon degeneration, gliosis, and cell death.16 One recently recognized consequence of injury is disruption of the axon initial segment (AIS).17 AIS are characterized by a high density of voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels that are clustered and maintained at these sites by the cytoskeletal and scaffolding proteins ankyrinG (ankG) and βIV spectrin.18 The AIS is the site of action potential initiation and is a key regulator of neuronal output. Therefore, any alteration of the AIS will affect the excitability of neurons and the circuits in which they function. Indeed, recent studies have shown that the AIS is dismantled after stroke and nerve crush,19 and its molecular composition and length are altered after synaptic deprivation, during chronic depolarization, in epilepsy, and in a mouse model of autism.20–24 Thus, disruption of AIS structure and function is emerging as a key consequence and/or contributor to nervous system dysfunction.25

Here, we sought to determine if exposure to a blast wave causes mTBI and to elucidate cellular and/or molecular changes in the brain that occur as a consequence. We found that exposure to a single blast wave can induce long-lasting changes in memory and induce shortening of the AIS. Finally, using an anatomically accurate computational model of a cortical neuron,26 we demonstrate that decreasing AIS length increases the interspike interval of repetitively spiking cells. Our results support the conclusion that exposure to a single blast wave causes memory deficits and that altered AIS structure may be one consequence of this injury.

Methods

Animals

Rats were housed at Baylor College of Medicine. All experiments were performed in accordance with all National Institutes of Health guidelines for the humane treatment of animals. There were 48 male Sprague Dawley rats used for these experiments: 24 animals were exposed to a single blast and 24 cage mates were used as controls. Access to food and drink was ad libitum. Two weeks after blast wave exposure, all animals were sacrificed, and brains were used for immunostaining or immunoblotting. All behavioral tasks and data analysis were performed by an observer blinded to the injury status.

Blast injury

The blast wave was generated using a compressed air-driven shock tube (Figs. 1A, 1B). The shock tube consists of a compression chamber and a tube that is 1.25 m long. The blast wave was measured using a piezoelectric sensor (PCB Piezotronics) positioned beside the rat's head. The amplitude of the blast wave is highly reproducible (Fig. 1C) and is controlled by the amount of input pressure used (Figs. 1D, 1E). The time to peak and time to 1/2 maximum of the blast overpressure were relatively constant for a given tube length (Fig. 1F).

FIG. 1.

A compressed air-driven shock tube. (A) A photograph of the shock tube. Animals are positioned inside the end of the tube in a harness. (B) Schematic of the shock tube. (C) The average of the waveforms used in these experiments (the region in gray represents±standard error of the mean). (D) Three waveforms generated using different input pressures. (E) The amplitude of the overpressure scales linearly with the input pressure. (F) For a 1.25 m tube, the time-to-peak and to 1/2 max are relatively constant for the different input pressures used. (G) Frames from a high-speed video taken during a blast exposure. The original video was taken at 1000 frames/sec.

Rats (200–250 g) were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (80 mg/kg ketamine and 16 mg/kg xylazine). After demonstrating a lack of response from a toe pinch, rats were placed in a holder inside the tube, approximately 20 cm from the end of the tube. The rats were prone and facing the blast wave, with the pressure transducer placed on the right side of the head near the whisker pad. The rat's head was not held in place or stabilized in any manner. Control animals were anesthetized, restrained, and placed in the tube, but not exposed to a blast wave.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured using the CODA™ non-invasive monitoring system (Kent Scientific). While under anesthesia, a baseline blood pressure was taken before placing the animal in the tube. Additional blood pressure measurements were taken immediately after the blast exposure and at 30 and 60 min after blast wave exposure. Ten measurements were taken at each time point for each animal and averaged. Temperature was monitored and maintained using a heating pad. The CODA system measured five parameters: systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure, tail blood volume, and blood flow. Animals were also weighed before the blast wave exposure, and 24 h, 48 h, 10 days, and 2 weeks after blast wave exposure.

Rotarod

Before all experiments involving motor performance or behavior analyses, animals were individually handled on 3 consecutive days for 15 min each. Rats were allowed to habituate to the behavior rooms for 1 h each day before the onset of the task. If an animal performed more than one task on a given day (i.e., rotarod and beam walking), it was allowed to rest for 1 h between tasks. For the rotarod, animals were trained for 5 consecutive days before blast exposure. On the first day of training, rats were required to sit on the rod for 30 sec and then walk at 5 rpm for 90 sec. On days 2–5 of training, and subsequent days after blast wave exposure, the rod constantly accelerated from 4–40 rpm in 5 min. Each animal was tested three trials per day, with a 10-min break between each trial. The latency to fall from the rod for each trial was recorded and averaged.

Beam walk

Rats were trained to avoid white noise and bright lights by traversing a beam (4 cm×102 cm) to reach a dark box. Animals were trained for 4 consecutive days before blast wave exposure. On the first day of training, rats were placed in the dark box to habituate and then moved out increasing distances from the dark box to expose them to the lights and white noise. On the following training days and testing days (after blast wave exposure), rats were placed at the end opposite of the dark box and the amount of time needed to reach the box was recorded. Rats were given four trials per day; the three fastest times were recorded and averaged. For both beam walk and rotarod experiments, animals were tested 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 5 days, 7 days, 10 days, and 14 days after blast wave exposure. To account for individual differences in these tasks, times from testing days (after blast wave exposure) were normalized by division to each animal's average time on the last day of training (before blast wave exposure).

Novel object recognition test

For the novel object recognition test,27 rats were allowed to explore the testing apparatus (an empty cage otherwise identical to the home cage) for 10 min for 3 consecutive days before the task. On the day of the task, animals were allowed to explore two identical objects for 10 min (training phase). One hour later, animals were placed back in the test cage with one object from the training phase and one novel object, which was the same size and shape but a different color. Animals were allowed to explore these two objects for 4 min. Both of these sessions were recorded. To score this task, a blinded observer watched a video recording of both phases of the task, and measured how much time was spent interacting with either object. The percent time per object was then calculated (i.e., 100*(Time with Object 1)/(Time with Object 1+Time with Object 2)). To verify that the blast wave exposure did not impair the ability to distinguish between white and black objects, animals were placed in a box with a moving black and white gradient to elicit an optokinetic response.28 All animals examined (n=7 blast, 4 control) were able to distinguish between white and black (data not shown).

Antibodies

Antibodies against ankyrinB, Kv1.2, and βIV spectrin were described previously.29 βII spectrin antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. αII spectrin and Actin antibodies were purchased from Millipore. The monoclonal ankG, (N106/36 and N106/20), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, N206A/8), and Nav1.6 (K87/10A) antibodies were purchased from the UC Davis/NIH funded Neuromab monoclonal antibody resource. Mouse pan-Nav and pan-Neurofascin antibodies were described previously.30 The polyclonal Iba-1 antibody was purchased from Wako Chemicals. The BDNF antibody was purchased from R&D Sytems. The albumin antibody was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories. The monoclonal GFAP antibody and polyclonal GAPDH antibody were purchased from Sigma. The monoclonal βAPP antibody was purchased from Invitrogen. All fluorescent secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as described previously.30 Whole brains (except for the cerebellum) were collected 2 weeks after exposure to the blast. Quantification of the blots was performed using ImageJ (NIH). Lanes for each blot were selected, plotted, and the area of each peak determined; controls and blast animals were then compared.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Two weeks after blast wave exposure, rats were sacrificed by isoflurane overdose, and the brains were post-fixed for 105 min in 4% PFA, pH 7.2 at 4°C. Brains were then transferred to 20% sucrose and allowed to equilibrate overnight at 4°C. The 35 μm sections were cut using a freezing stage microtome. For the AIS analysis, subsequent staining was performed using free floating sections at 4°C with gentle rocking. Sections were blocked for 1 h in PBTGS (10% goat serum and 0.1% TX-100 diluted in 0.1M phosphate buffer). Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies (diluted in PBTGS) for 2 days, washed three times with PBTGS, incubated with secondary antibodies for 4 h, and washed with PBTGS, 0.1M PB, and 0.05M PB for 5 min each. Sections were mounted onto glass slides and imaged.

For all AIS analysis, three-dimensional volume z-stacks were used. To measure the length of the AIS in area CA1 of the hippocampus, two z-stacks were taken per hippocampus with a 40× objective (0.75 NA), for a total of four hippocampal z-stacks per animal. Z-stacks were loaded in ImageJ, and the length of 10 randomly selected AIS was measured using the segmented line tool by an observer blinded to the injury status. To assess the number and length of the AIS in the cortex, seven z-stacks were taken of the cortex, starting medially, just dorsal to the corpus callosum, and moving laterally. The top of the field of view was aligned with the dorsal edge of Layer 2/3 cells. Images were taken from brain sections −3.42 mm±.42 mm and 24 mm±.36 mm relative to bregma.

We then used MATLAB to filter the raw images to remove out-of-focus fluorescence and increase the contrast of each AIS. Each pixel was then converted to white or black based on a user-defined threshold, and any remaining non-AIS fluorescence was eliminated by using a morphological filter to exclude objects that are not shaped like an AIS or that are less than 15 μm in length (e.g., nodes of Ranvier). The algorithm then counted the number of AIS and measured their length. We conducted the AIS measurements on 14 z-stacks×4 tissue sections (2 rostral and 2 caudal) collected from medial to lateral regions of the cortex. We measured seven blast and five control animals. Thus, for each animal, we had 56 individual z-stacks and a total of 392 z-stacks for blast animals and 280 z-stacks for control animals.

For immunostaining with GFAP, Iba-1, and albumin antibodies, sections were mounted on coverslips, incubated with primary antibodies overnight, and then labeled with secondary antibodies for 1 h. Analysis of these injury markers was performed in the cortex, corpus callosum, and hippocampus at bregma −3.42 mm±.42 mm on single images. Two images of both the cortex and hippocampus were obtained from each hemisphere using a 10× (0.3 NA) objective. Three images of the corpus callosum were taken, one directly ventral to the midline and one on either side, using a 20× objective (0.8 NA) or 40× objective (0.75 NA). For each image, a histogram of pixel intensities was then generated in MATLAB, and the percent of the pixels above threshold was determined. Control images were used to determine the threshold, which was defined as the cutoff value that 28-33% of pixels in control images were above.

Computer model

Modeling was performed in Neuron v7.1 (http://www.neuron.yale.edu/neuron/). A previously published model for action potential initiation26 was modified by decreasing the length of the AIS by the experimentally observed differences.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 5 for Mac. For the weight, hemodynamics, beam walking, and rotarod tasks, a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. For the injury marker and immunoblot analysis, a Student t test was used to compare animals exposed to a blast with controls, and then a Bonferroni correction was performed for multiple comparisons. For the novel object recognition task, a one-way ANOVA was used for the training phase, and a Student t test was used for the testing phase. A Student t test was also used for the hippocampal length analysis. The cortical AIS analysis was performed using a two-way ANOVA. p<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Generation of the blast wave

To determine the effects of blast wave exposure on the brain, we built a compressed air driven shock tube (Fig. 1A,B). When measured inside and near the end of the tube, the shock tube generates a highly reproducible shockwave (Fig. 1C) that is qualitatively similar to one resulting from an explosive blast. The amplitude of the pressure wave can be adjusted by changing the amount of input pressure (Figs. 1D,E), and the duration of the positive phase of the pressure wave can be reduced by increasing tube length (data not shown). For the 1.25 m long tube used in these experiments, the time to peak and time to 1/2 max remain consistent across different input pressures (Fig. 1F).

We exposed 24 male Sprague-Dawley rats to a single blast wave with amplitude of 74 kPa (Fig. 1C). We selected this amplitude because the next highest pressure wave we tested (amplitude of 98 kPa) resulted in lung trauma and death, whereas amplitudes of 74 kPa did not result in the death of any animals. Anesthetized rats were placed prone inside the tube in a harness that left their heads exposed to the blast wave. A pressure transducer was placed immediately adjacent to the right side of the head near the whisker pad to measure the pressure wave at the head. We used a high-speed video camera (1000 frames/sec) to monitor the rat during exposure to the blast wave. Sample frames during exposure to the blast wave are shown in Figure 1G.

A single blast wave does not affect physiology or motor performance

Rats exposed to a single blast wave showed no physical impairment. With respect to mean blood pressure (Fig. 2A), we observed a significant main effect over time (p<0.01), but no significant main effect for blast (p=0.8) or interaction (p=0.5). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, tail blood volume, and blood flow also did not differ between blast-exposed animals and controls (Figs. 2B–E). We observed no difference in weight gain among blast-exposed and control rats for up to 2 weeks (Fig. 2F). We also measured motor performance and coordination. Using the narrow beam-walk task (Fig. 2G) and accelerating rotarod (Fig. 2H), we found no difference between control and blast-exposed rats.

FIG. 2.

Exposure to a single blast wave does not cause changes in hemodynamics, weight gain, or motor behavior. (A-E) Mean blood pressure, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, tail blood flow, and tail blood volume were not significantly different in control animals compared with animals exposed to a blast immediately after blast exposure (post), 30 min after blast exposure (30' Post), or 1 h after blast exposure (60' Post). (F) Animals exposed to a single blast do not show any differences in weight at 48 h, 10 days, or 2 weeks after blast exposure. (G, H) Animals exposed to a single blast did not show impairment on the beam walking task (G, p>0.05) or the accelerating rotarod (H, p>0.05). Error bars indicate±standard error of the mean.

A single blast wave does not increase the expression of injury-associated proteins

To determine if exposure to a blast wave induces brain pathology similar to other TBI models, we evaluated changes in the expression of Iba1 (Figs. 3A,C), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Fig. 3B,D), and albumin (immunofluorescence not shown) by immunofluorescence microscopy and immunoblot analysis. Iba1 is a marker for activated microglia and has been used as a measure of the inflammatory response after brain injury.31 GFAP is upregulated by astrocytes after injury and is commonly used as an indicator of astrogliosis,32 and albumin immunostaining can be used to evaluate vascular permeability after injury. Quantification of the immunostaining in three different brain regions (cortex, corpus callosum, hippocampus) showed that with the exception of Iba1 immunostaining, for most brain regions, we observed no significant difference in immunoreactivity at 24 h or 2 weeks after rats were exposed to a single blast (Figs. 3E–J). Neither Iba1 nor GFAP immunostaining revealed changes in the morphology of microglia or astrocytes, respectively (Figs 3A,C). We also counted the total number of Iba1-labeled cells and found no difference between blast-exposed and control rats in either the hippocampus or cortex at 24 h or 2 weeks after blast exposure (Fig. 3K). We also labeled all cells using the fluorescent nuclear stain Hoechst and counted the total number of cells in layers 2/3 of the cortex, measuring seven different regions from medial to lateral positions along the cortex, to determine if exposure to a single blast results in loss of cells. We observed no significant difference between blast-exposed rats and control rats, however (Fig. 3L).

FIG. 3.

The expression levels of Iba1, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and albumin are not significantly altered at 24 h or 2 weeks after blast exposure. (A-D) Immunostaining of cortex of blast-exposed and control rats using antibodies against Iba1 (A, C) and GFAP (B, D). (E-J) The ratio of immunofluorescence between blast-exposed and control rats in the cortex (CTX), corpus callosum (CC), and hippocampus (Hipp) 24 h and 2 weeks after blast exposure. After correcting for multiple comparisons, the only significant difference between blast and control animals was Iba1 immunoreactivity in the corpus callosum at 24 h after blast, and hippocampus at 2 weeks after blast. (K) The number of Iba1-labeled cells in hippocampus and cortex from control and blast-exposed rats at 24 hrs (5 blast-exposed and 4 control rats) and 2 weeks (7 blast-exposed and 4 control rats). (L) The number of Hoechst-labeled cells per field of view (FOV) in seven areas across the CTX from medial to lateral positions. Measurements were made at 2 weeks after blast-exposure (seven blast-exposed and four control rats). Error bars indicate±standard error of the mean. Scale bar=20 μm.

To further evaluate changes in protein expression levels in the brain, we performed immunoblot analysis of cortical homogenates made from control and blast-exposed rats (Fig. 4). We examined PSD-95, a postsynaptic density protein, βAPP, GFAP, αII spectrin, GAPDH, and actin, the latter two proteins serving as loading controls. We observed no significant difference in the amounts of these proteins 2 weeks after blast exposure (Fig. 4B). Because αII spectrin is a potent substrate for calpain and caspase mediated proteolysis, and has previously been proposed as a biomarker for brain injury, we also examined the production of calpain (150 kD) and caspase (120 kD) dependent spectrin breakdown products.34,35 However, we observed no significant difference between blast and control brains, however. Together, these results suggest that exposure to a single 74 kPa blast wave does not cause injury sufficient to induce upregulation of commonly used injury markers, or proteolysis of spectrin.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot analysis of brains from blast-exposed rats shows no changes in the expression of injury markers 2 weeks after blast exposure. (A) Immunoblot analysis for PSD-95, βAPP, GFAP, and α-II spectrin. (B) Quantification of expression levels showed no significant differences between controls and animals exposed to a single blast. Actin and GAPDH were used as loading controls. Error bars indicate±standard error of the mean.

Exposure to a single blast wave impairs memory

Because memory loss or impairment is one criterion for mTBI, we used the novel object recognition task27 to evaluate recognition memory36 and cognitive function in rats exposed to a single blast wave. Rats were trained for 10 min with identical objects (Fig. 5A). During the training period, both control and blast-exposed rats spent equal amounts of time investigating the objects (Fig. 5C). The rats were then removed from the objects for a 1-h interval, and then returned to the testing cage for 4 min, but with one novel object replacing a familiar object (Fig. 5B). We found that 2 weeks after exposure to a blast wave, rats spent significantly less time with the novel object compared with controls (Fig. 5D). Thus, exposure to a blast wave impairs cognitive function.

FIG. 5.

Exposure to a blast causes significant cognitive impairment and decrease in the length of the axon initial segment (AIS) in the hippocampus. (A, B) Schematic of the object recognition task. There was a 1-h interval between training and testing. (C) Control and blast-exposed rats spent equal amounts of time with both objects during the training phase. (D) Blast-exposed animals spent significantly less time with the novel object during testing compared with controls. (E) Immunostaining of the hippocampus using antibodies against βIV spectrin. The white box labels the area that was used for the length quantification. (F) Higher magnification image of βIV spectrin immunostaining in area CA1 of the hippocampus. The scale bar is 50 μm. (G) There is a significant decrease in the length of the AIS in injured animals compared with controls (p<0.05). Error bars indicate±standard error of the mean.

Exposure to a single blast wave decreases AIS length

How can a blast wave disrupt cognitive function without inflammation, gliosis, neuron death, or axonal degeneration? One possible explanation is that blast disrupts the normal excitable properties of brain neurons by altering ion channel complement, density, and/or distribution. If true, then one readout of altered excitability might be changes in the length or position of the AIS, because recent studies have shown that synaptic deprivation, altered membrane potential, or chronic depolarization can induce changes such as these,20,21,23 and injury can even dismantle the AIS.19 To measure AIS length, we immunostained CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons 2 weeks after exposure to a blast wave using antibodies against βIV spectrin (Fig. 5E,F). We then performed a blinded manual measurement of AIS length. Unfortunately, we were unable to reliably count the number of AIS in the hippocampus because of its complex cytoarchitecture where AIS are often intertwined. Nevertheless, consistent with the hypothesis that neuronal excitability is altered as a consequence of blast injury, we found that AIS were significantly shorter in blast-exposed animals when compared with controls (Fig. 5G).

To determine if disruption of AIS length is a common feature among blast-exposed neurons or if blast exposure results in the loss of AIS, we developed an automated method to count the number and length of AIS in a volume of layer 2/3 cortical neurons. We immunolabeled rostral and caudal sections from the cortex (−3.42 mm±.42 mm [Fig. 6A–D] and .24 mm±.36 mm [Fig. 6E–H] relative to bregma) with antibodies against βIV spectrin and ankG. Next, seven z-stacks were collected from each brain hemisphere, starting medially just above the corpus callosum and moving out laterally. These z-stacks were processed using a MATLAB algorithm to count the number and length of labeled AIS. We found the number of AIS was not significantly different between blast-exposed rats and controls (Fig. 6A,B,E,F), consistent with the conclusion that exposure to a single blast wave does not cause cell death or complete loss of AIS.

FIG. 6.

Exposure to a single blast wave causes a significant decrease in the length of the axon initial segment in the cortex. (A–H) Axon initial segment (AIS) were counted and the length was determined in two different locations in the cortex from seven blast-exposed and five control rats. Data from rostral regions are shown in A-D, while data from caudal regions are shown in E-H. A,B, E, F, The number of AIS in injured animals compared with controls was not significantly different from control animals (p>0.05 for βIV and ankG immunostaining). C, D, G, H, The lengths of the βIV spectrin and ankG-labeled AIS were significantly shorter in blast-exposed animals compared with controls (C, D, G, p<0.05 and H, p=0.08; two-way analysis of variance, significant main effect for blast exposure across all positions). A total of 14,078 and 11,575 AIS were measured from blast-exposed and control rats, respectively. (I) Immunoblot analysis of brain homogenates for AIS proteins shows no changes in the levels of AIS proteins or the generation of breakdown products in blast exposed animals. (J) Quantification of immunoblots revealed no significant changes in protein levels except for a decrease in ankB in blast exposed animals.

The length of the AIS, however, was consistently and significantly shorter in blast-exposed animals compared with controls (Figs. 6C,D,G,H). In some brain regions we observed as much as a 4.7% decrease in AIS length. On average, we observed a 1.8% and 2.5% decrease in AIS length in rostral and caudal brain regions, respectively. The shorter AIS length in ankG-labeled brain sections compared with βIV spectrin-labeled brain sections is most likely from a higher sensitivity of the βIV spectrin antibody because βIV spectrin localization depends on ankG,37 and the reduction in AIS length was consistent for both ankG and βIV spectrin antibodies. Together, these results suggest that although exposure to a single blast does not dismantle the AIS, it does lead to decreased AIS length.

To further evaluate changes in the levels of proteins found at the AIS and in axons, we performed immunoblot analysis of cortical homogenates made from control and blast-exposed rats using antibodies against the AIS proteins ankG, Nav channels (Pan Nav), neurofascin (NF)-186, βIV spectrin, and Kv1.2 (Fig. 6I).18 We observed no significant difference in the amounts of these proteins, however, 2 weeks after blast exposure (Fig. 6J). Intriguingly, we did observe a significant decrease (p<0.01) in the amount of ankyrinB (ankB), a cytoskeletal scaffold enriched not at the AIS, but instead in the distal axon and that is thought to contribute to the position of the distal end of the AIS.38

Shortening of the AIS leads to altered neuronal excitability

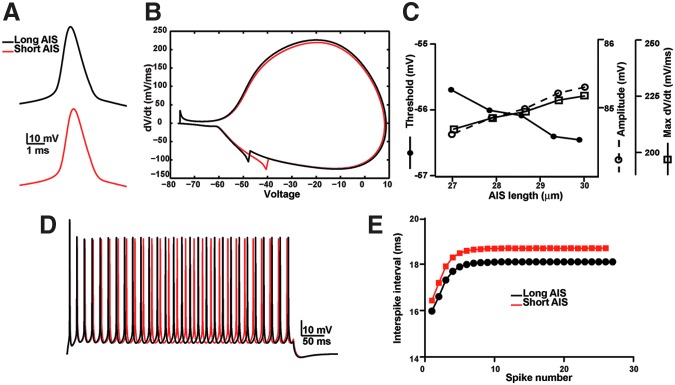

What consequence does a 1-4% decrease in AIS length after exposure to a blast have for the excitable properties of a neuron? To begin to investigate this question and to overcome the technical challenges associated with direct measurement of potentially very small changes in neuronal excitability in the blast-exposed brain, we used an anatomically accurate computational model of a pyramidal neuron26 to determine if small AIS length changes can affect excitability. We used a range of experimentally determined AIS lengths from control and blast-exposed rats (27–30 μm). We first examined the shape of the action potential using model neurons with AIS of length 30 μm (long) and 28.65 μm (short). By shortening the length of the AIS, we observed no major change in the shape of the action potential (Fig. 7A,B), but a small increase in AP threshold (Fig. 7C). In addition, the shortened AIS decreased the amplitude and maximum rate of rise (dV/dt) (Fig. 7C). We next simulated a sustained depolarizing current to evaluate the consequence of AIS shortening on interspike interval (ISI), because this parameter is thought to underlie neural coding and play an important role in determining whether a train of spikes generates a post-synaptic response.39,40 We found that decreasing AIS length (from 30 to 28.65 μm) increased ISI (Fig. 7D,E). Together, these simulations suggest that even small changes in AIS length, like those described here after exposure to a blast, could lead to alterations in neuronal excitability and neural coding.

FIG. 7.

A computational model shows that a shorter axon initial segment (AIS) reduces neuronal excitability and alters the interspike interval. (A) Action potential shape for model neurons with AIS lengths of 30 μm (long AIS, black) or 28.65 μm (short AIS, red). (B) Phase plot of action potentials shown in A. (C) The amplitude of the action potential, threshold (defined as 20 mV/ms) and max dV/dt as a function of AIS length. (D) Voltage response of a 500 ms stimulation for neurons with AIS lengths of 30 μm (long AIS, black) or 28.65 μm (short AIS, red). (E) Interspike interval as a function of spike number for a model neuron with a long AIS (30 μm, black) or a short AIS (28.65 μm, red).

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence that exposure to a blast wave can induce mTBI. This conclusion is based on several experimental observations. First, exposure to a single blast wave impairs performance on the novel object recognition task. Second, exposure to a blast wave decreases the length of the AIS. While these results provide support for the concept of blast-induced mTBI, several important questions and caveats remain. In particular, we report here only phenomena associated with blast exposure and do not know how AIS length is altered, why recognition memory is impaired, or if the two are connected in any way. Although we observed altered AIS length in the hippocampus and performance on the novel object recognition task was impaired, there is disagreement about the role of the hippocampus in the novel object recognition task.36,41

A major limitation to identify the mechanisms of blast-induced brain injury is the availability of appropriate animal models. Here, we used a compressed-air blast tube to simulate a blast wave produced by an explosive device. While our blast tube has the distinct advantages of being simple to operate and producing highly reproducible and “adjustable” blast waves, we acknowledge several limitations. For example, the rise time of the blast overpressure is longer than that of a blast wave generated by an explosion, (although a wide range of blast overpressure amplitudes and durations have been used).42–45 It is not known, however, which component(s) of the blast wave causes mTBI (the rapid change in pressure, the amplitude of the pressure wave, or the duration of the pressure wave). Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that the model used here produced symptoms consistent with a mTBI including memory impairment. Further, our model produced only a mild injury because it does not disrupt motor performance, increase the expression of injury markers, or cause axon degeneration or proteolysis of axonal cytoskeletal proteins.

As with other models of brain injury, additional limitations include the problem of scale and anatomy: can a rat head and brain be compared with a human head and brain? How does a stressful environment influence the severity of the mTBI? Are the symptoms from the blast wave exposure alone exacerbated by secondary or tertiary injuries associated with the blast? And does exposure to more than one blast wave potentiate symptoms? Given these many qualifications, it is clear that no single blast model will faithfully recapitulate all of the conditions experienced by a soldier exposed to an explosive device. Thus, it is important to compare results and outcome measures across a broad spectrum of injury models, from the one described here to those that use blunt force or other methods of generating a blast wave.

While some studies of blast-induced brain injury have reported gliosis and axon degeneration,45 we did not observe any of these in our model. Instead, we measured a significant decrease in AIS length. Previous studies have shown that disruption or alterations in AIS position, length, or integrity are common in a variety of nervous system injury and disease models.17 For example, chronic depolarization of neurons in vitro caused a distal movement of the AIS and resulted in neurons that were less excitable.20 On the other hand, synaptic deprivation led to the expansion of the AIS and neurons that were more excitable.21 Similarly, in a mouse model of Angelman syndrome where the resting membrane potential is more hyperpolarized, the AIS is longer.23 Together, these examples point to the idea that altered intrinsic membrane properties lead to homeostatic alterations in AIS length: Increased somatodendritic excitability results in a shorter AIS and decreased somatodendritic excitability a longer AIS. These plastic changes in AIS length would tend to offset changes in intrinsic somatodendritic membrane excitability.

Although increased somatodendritic excitability has not previously been reported to be a consequence of blast-induced mTBI, we propose that the decreased AIS length observed after exposure to a blast injury is an indicator of increased neuronal and/or network excitability. Increased somatodendritic excitability could result from a variety of chronic changes in response to blast including altered ion channel function, altered synaptic function, glutamate spillover, or somatodendritic plasmalemmal disruption leading to increased membrane permeability, all of which have been reported in various models of brain injury.46–48 Further, acute stretch-induced axonal injury has been shown to promote Na+ influx.49 Alternatively, blast injury could lead directly to shortening of the AIS through changes in gene expression (e.g., decreased ankG expression) or the structure of the distal axonal cytoskeleton.38

The changes in AIS length reported here were derived from many thousands of AIS and are the average change across the entire population of neurons we observed. Because the decrease in AIS length is only 1-4%, however, and our simulations suggest that changes in amplitude and threshold are in the sub-mV range, it is impractical using current technologies to verify the increased excitability and consequence of a shortened AIS length by directly recording from the neurons of blast-exposed rats and correlating those properties with AIS length. Instead, we used a computational model to explore how small changes in AIS length might impact neuronal excitability; we found small changes in action potential amplitude, threshold, and in the interspike interval. Future studies using Ca2+-activated fluorescent reporters with high temporal resolution and signal to noise ratio may permit a direct measurement of altered neuronal excitability in models of blast-induced mTBI.

The changes in AIS structure reported here are likely to occur over days and weeks.20,50 If altered AIS structure is related to mTBI-induced cognitive impairment, then a relatively long therapeutic window may exist to preserve normal brain function.

Conclusion

Our results support the idea that exposure to a blast wave alone can produce a mTBI that includes both impaired memory and altered neuronal properties. Future studies will be needed to further dissect the molecular mechanisms underlying the structural changes in neurons and to determine whether altered AIS properties cause functional impairment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Eva Ng and Yanhong Liu for technical help. We thank Cameron Cowan for help measuring the optokinetic response of rats. This work was supported by grant W81XWH-08-2-0145 from the Department of Defense.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Okie S. Traumatic brain injury in the war zone. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2043–2047. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling G.S. Ecklund J.M. Traumatic brain injury in modern war. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:124–130. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834458da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elsayed N.M. Toxicology of blast overpressure. Toxicology. 1997;121:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(97)03651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayorga M.A. The pathology of primary blast overpressure injury. Toxicology. 1997;121:17–28. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(97)03652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung L.Y. VandeVord P.J. Dal Cengio A.L. Bir C. Yang K.H. King A.I. Blast related neurotrauma: a review of cellular injury. Mol Cell Biomech. 2008;5:155–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritenour AE. Baskin TW. Primary blast injury: update on diagnosis, treatment. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S311–317. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817e2a8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champion H.R. Holcomb J.B. Young L.A. Injuries from explosions: physics, biophysics, pathology, and required research focus. J. Trauma. 2009;66:1468–1477. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a27e7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ling G. Bandak F. Armonda R. Grant G. Ecklund J. Explosive blast neurotrauma. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:815–825. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cernak I. Noble-Haeusslein L.J. Traumatic brain injury: an overview of pathobiology with emphasis on military populations. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:255–266. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilk J.E. Thomas J.L. McGurk D.M. Riviere L.A. Castro C.A. Hoge C.W. Mild traumatic brain injury (concussion) during combat: lack of association of blast mechanism with persistent postconcussive symptoms. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25:9–14. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181bd090f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taber K.H. Warden D.L. Hurley R.A. Blast-related traumatic brain injury: what is known? J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006;18:141–145. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:398–402. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll L.J. Cassidy J.D. Peloso P.M. Borg J. von Holst H. Holm L. Paniak C. Pepin M. Prognosis for mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Rehabil. Med. 2004;(Suppl 43):84–105. doi: 10.1080/16501960410023859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoge C.W. McGurk D. Thomas J.L. Cox A.L. Engel C.C. Castro C.A. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:453–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elder G.A. Mitsis E.M. Ahlers S.T. Cristian A. Blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2010;33:757–781. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradbury E.J. McMahon S.B. Spinal cord repair strategies: why do they work? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:644–653. doi: 10.1038/nrn1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buffington S.A. Rasband M.N. The axon initial segment in nervous system disease and injury. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011;34:1609–1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasband MN. The axon initial segment and the maintenance of neuronal polarity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nrn2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schafer DP. Jha S. Liu F. Akella T. McCullough LD. Rasband MN. Disruption of the axon initial segment cytoskeleton is a new mechanism for neuronal injury. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13242–13254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3376-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grubb M.S. Burrone J. Activity-dependent relocation of the axon initial segment fine-tunes neuronal excitability. Nature. 2010;465:1070–1074. doi: 10.1038/nature09160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuba H. Oichi Y. Ohmori H. Presynaptic activity regulates Na(+) channel distribution at the axon initial segment. Nature. 2010;465:1075–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature09087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wimmer V.C. Reid C.A. So E.Y. Berkovic S.F. Petrou S. Axon initial segment dysfunction in epilepsy. J. Physiol. 2010;588:1829–1840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.188417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaphzan H. Buffington S.A. Jung J.I. Rasband M.N. Klann E. Alterations in intrinsic membrane properties and the axon initial segment in a mouse model of angelman syndrome. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:17637–17648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4162-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X. Kumar Y. Zempel H. Mandelkow E.M. Biernat J. Mandelkow E. Novel diffusion barrier for axonal retention of Tau in neurons and its failure in neurodegeneration. Embo. J. 2011;30:4825–4837. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grubb M.S. Shu Y. Kuba H. Rasband M.N. Wimmer V.C. Bender K.J. Short- and long-term plasticity at the axon initial segment. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:16049–16055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4064-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kole M.H. Ilschner S.U. Kampa B.M. Williams S.R. Ruben P.C. Stuart G.J. Action potential generation requires a high sodium channel density in the axon initial segment. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:178–186. doi: 10.1038/nn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bevins R.A. Besheer J. Object recognition in rats and mice: a one-trial non-matching-to-sample learning task to study ‘recognition memory.’. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Douglas R.M. Alam N.M. Silver B.D. McGill T.J. Tschetter W.W. Prusky G.T. Independent visual threshold measurements in the two eyes of freely moving rats and mice using a virtual-reality optokinetic system. Vis. Neurosci. 2005;22:677–684. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogawa Y. Schafer D.P. Horresh I. Bar V. Hales K. Yang Y. Susuki K. Peles E. Stankewich M.C. Rasband M.N. Spectrins and ankyrinB constitute a specialized paranodal cytoskeleton. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:5230–5239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0425-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schafer DP. Bansal R. Hedstrom KL. Pfeiffer SE. Rasband MN. Does paranode formation and maintenance require partitioning of neurofascin 155 into lipid rafts? J Neurosci. 2004;24:3176–3185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5427-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong H.K. Ji K.M. Kim B. Kim J. Jou I. Joe E.H. Inflammatory responses are not sufficient to cause delayed neuronal death in ATP-induced acute brain injury. PLoS One. 2011;5:e13756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svetlov S.I. Prima V. Kirk D.R. Gutierrez H. Curley K.C. Hayes R.L. Wang K.K. Morphologic and biochemical characterization of brain injury in a model of controlled blast overpressure exposure. J. Trauma. 2010;69:795–804. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bbd885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burggraf D. Trinkl A. Burk J. Martens H.K. Dichgans M. Hamann G.F. Vascular integrin immunoreactivity is selectively lost on capillaries during rat focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Brain Res. 2008;1189:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siman R. Baudry M. Lynch G. Brain fodrin: substrate for calpain I, an endogenous calcium-activated protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:3572–3576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mondello S. Robicsek S.A. Gabrielli A. Brophy G.M. Papa L. Tepas J. Robertson C. Buki A. Scharf D. Jixiang M. Akinyi L. Muller U. Wang K.K. Hayes R.L. alphaII-spectrin breakdown products (SBDPs): diagnosis and outcome in severe traumatic brain injury patients. J Neurotrauma. 2010;27:1203–1213. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barker G.R. Warburton E.C. When is the hippocampus involved in recognition memory? J. Neurosci. 2011;31:10721–10731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6413-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y. Ogawa Y. Hedstrom K.L. Rasband M.N. {beta}IV spectrin is recruited to axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier by ankyrinG. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:509–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galiano M.R. Jha S. Ho T.S. Zhang C. Ogawa Y. Chang K.J. Stankewich M.C. Mohler P.J. Rasband M.N. A distal axonal cytoskeleton forms an intra-axonal boundary that controls axon initial segment assembly. Cell. 2012;149:1125–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerstner W. Kreiter A.K. Markram H. Herz A.V. Neural codes: firing rates and beyond. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:12740–12741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rathbun DL. Alitto HJ. Weyand TG. Usrey WM. Interspike interval analysis of retinal ganglion cell receptive fields. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:911–919. doi: 10.1152/jn.00802.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delcour M. Russier M. Amin M. Baud O. Paban V. Barbe M.F. Coq J.O. Impact of prenatal ischemia on behavior, cognitive abilities and neuroanatomy in adult rats with white matter damage. Behav. Brain Res. 2012;232:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cernak I. Wang Z. Jiang J. Bian X. Savic J. Cognitive deficits following blast injury-induced neurotrauma: possible involvement of nitric oxide. Brain Inj. 2001;15:593–612. doi: 10.1080/02699050010009559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moochhala S.M. Md S. Lu J. Teng C.H. Greengrass C. Neuroprotective role of aminoguanidine in behavioral changes after blast injury. J. Trauma. 2004;56:393–403. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000066181.50879.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long J.B. Bentley T.L. Wessner K.A. Cerone C. Sweeney S. Bauman R.A. Blast overpressure in rats: recreating a battlefield injury in the laboratory. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:827–840. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Svetlov S.I. Prima V. Glushakova O. Svetlov A. Kirk D.R. Gutierrez H. Serebruany V.L. Curley K.C. Wang K.K. Hayes R.L. Neuro-glial and systemic mechanisms of pathological responses in rat models of primary blast overpressure compared to “composite” blast. Front Neurol. 2012;3:15. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwata A. Stys P.K. Wolf J.A. Chen X.H. Taylor A.G. Meaney D.F. Smith D.H. Traumatic axonal injury induces proteolytic cleavage of the voltage-gated sodium channels modulated by tetrodotoxin and protease inhibitors. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4605–4613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0515-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singleton RH. Povlishock JT. Identification, characterization of heterogeneous neuronal injury, death in regions of diffuse brain injury: evidence for multiple independent injury phenotypes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3543–3553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5048-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hinzman J. Thomas T.C. Quintero J. Gerhardt G. Lifshitz J. Disruptions in the regulation of extracellular glutamate by neurons and glia in the rat striatum two days after diffuse brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1197–1208. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf J.A. Stys P.K. Lusardi T. Meaney D. Smith D.H. Traumatic axonal injury induces calcium influx modulated by tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1923–1930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01923.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hedstrom K.L. Ogawa Y. Rasband M.N. AnkyrinG is required for maintenance of the axon initial segment and neu ronal polarity. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183:635–640. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]