Abstract

Background

DNA methylation has been viewed as the most highly characterized epigenetic mark for genome regulation and development. Postnatal brains appear to exhibit stimulus-induced methylation changes because of factors such as environment, lifestyle, and diet (nutrition). The purpose of this study was to examine how extensively the brain DNA methylome is regulated by nutrition in early life.

Results

By quantifying the total amount of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in the thalamus and the hippocampus of postnatal malnourished mice and normal mice, we found the two regions showed differences in global DNA methylation status. The methylation level in the thalamus was much higher than that in the hippocampus. Then, we used a next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based method (MSCC) to detect the whole genome methylation of the two regions in malnourished mice and normal mice. Notably, we found that in the thalamus, 500 discriminable variations existed and that approximately 60% were related to neuronal development or psychiatric diseases. Pathway analyses of the corresponding genes highlighted changes for 9 genes related to long-term potentiation (5.3-fold enrichment, P = 0.033).

Conclusions

Our findings may help to indicate the genome-wide DNA methylation status of different brain regions and the effects of malnutrition on brain DNA methylation. The results also indicate that postnatal malnutrition may increase the risk of psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Malnutrition, Thalamus, Hippocampus, Mouse model, Global DNA methylation status, Whole genome methylation sequencing, Long-term potentiation, Psychiatric disorders

Background

Nutrition represents one of the major important variables that play crucial roles in the maturation and functional development of the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. Malnutrition exerts its effects during the brain growth spurt period, and it results in a variety of brain dysfunctions [2]. Growth deficits due to malnutrition in childhood increase the incidence of infectious diseases and lead to alterations in CNS function, which have been shown to delay psychomotor development [3]. Thus, understanding the pathological effects of malnutrition will provide critical insights into the neurodevelopmental process.

DNA methylation is among the best studied epigenetic modifications and is essential to mammalian development [4]. Specifically, the methylation of cytosine at CpG dinucleotides is an important regulatory modification of the genome [5]. Many epigenetic studies on DNA methylation have revealed that malnutrition during the perinatal period is highly correlated with abnormal neurodevelopment [6].

Studies of epigenetic modifications benefit substantially from improved next-generation sequencing methods, and recent technologies make it possible for accurate and large-scale CpG methylation profiling [7]. Methyl-sensitive cut counting (MSCC) is a NGS method used to profile the whole DNA methylome. The MSCC genome-scale analysis is based on the concept that locations of CCGGs largely reflect the distributions of all CpGs in the mouse genome [8].

In our study, we utilized a mouse model of male mice to avoid sex differences, as sexual dimorphism and sexual differentiation have been thought to underlie the sexual development of the brain and other organs, which could impact lifelong functions [9]. First, we detected the global DNA methylation status in the thalamus and the hippocampus of postnatal malnourished mice and normal mice. Because the two regions showed differences in global DNA methylation status, we employed MSCC to investigate DNA methylation to determine how extensively the two brain DNA methylomes were regulated by nutrition in early life.

Methods

Mouse husbandry

All animal care and use procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for Nutritional Sciences, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The parental mice in this study were purchased from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (SLAC, Shanghai, China) and housed under controlled conditions of 12 h light/12 h dark cycle at 23 ± 2°C and 35 ± 5% humidity. The parental mice had been raised for at least two generations on a control diet to attempt to minimize any trans-generational effects. The male offspring mice were weaned from the mothers at 20 days of age and were divided randomly into two groups (n = 7 in control group, n = 5 in famine group): the control group was given a standard diet (D12450B), and the famine group was fed with half of a low-protein diet (D06022301) [10]. After 6 weeks of artificial feeding, offspring mice were euthanized (the weights of the offspring mice were measured every week from weaning); the entire thalamus and hippocampus were dissected out and immediately stored at -80°C.

DNA preparation

Genomic DNA was isolated from ≥25 mg samples (thalamus and hippocampus of malnourished mice and normal mice) using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit following the standard protocol (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). To ensure the sample quality, a Thermo NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo, Wilmington, USA) was used to detect 260/280 nm UV absorbance ratios, and concentrations were determined with a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). DNA length was determined by an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) to ensure the integrity. We constructed two MSCC libraries for each of our two brain tissues that contained pooled DNA from the control group and the famine group. Pooled DNA was used to increase the sample concentration and diminish micro-dissection variations.

Global DNA methylation status detection and calculation

The MethylFlash™ Methylated DNA Quantification Kit (Fluorometric) was used to detect the total amount of 5mC in the thalamus and hippocampus according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY). Relative fluorescence units (RFU) at 530EX/590EMnm were measured using a SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) to calculate the global methylation status.

MSCC library construction

To detect cytosine methylation, MSCC utilized the restriction enzymes HpaII and MspI, which preferentially cut DNA based on its methylation status. Although both enzymes recognized the same restriction site CCGG, HpaII was a methylation-sensitive enzyme, while MspI was insensitive to methylation sites. Adaptors A and B were also created for MSCC and were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). Adaptor A contained a 5′ MmeI recognition site and a 5′ CG overhang, while adaptor B had a 3′ NN overhang. Both adapters also contained end sequences required for Illumina library construction. Then, we constructed a HpaII library and an Inverse library for our study. To correct the error during the experiment of the HpaII library and the Inverse library, we combined standard DNA in the two libraries that contained the same known methylated or no methylated sequences. Further details are provided in the Additional file 1: Supplementary Method.

Library sequencing and mapping

Before sequencing, we used a Perl script to extract 20 bp upstream and 20 bp downstream of every CCGG site from the whole mouse genome (mm9). Based on the UCSC Refseq database, we added annotation to these short sequences and established a CCGG sequence database. The two libraries were sequenced on the Hiseq2000 depth sequencing system (Illumina, San Diego, California). After sequencing, the HpaII library and the Inverse library data from the Hiseq2000 depth sequencing system (bcl document) were transformed into a fastq file using CASAVA software. The fastq file data were mapped to the CCGG sequence database that we constructed using MOM software. We then analyzed the number of reads in the same CCGG position to calculate the degree of methylation of each site. Standard DNA in each library was used to normalize the counts before estimating the methylation level, according to the method in Guo et al. [8].

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-tests were used to determine the differences in mouse weights and thalamus and hippocampus methylation levels between the control group and the famine group. For the MSCC data, we constructed a 200-bp non-overlapping windows profiling of the whole genome. Windows that involved more than 3 CpG sites sequenced were used for the subsequent analysis. For each of the 200-bp windows, we conducted Fisher exact tests to find different methylated regions (DMRs) with statistical significance (P < 0.05) and different levels of methylation changes (∆MSCC, either increase or decrease) >25%. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant in these analyses.

Pathway classification and enrichment analysis

Pathway analyses were performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) [11]. Pathway classification within DAVID used the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes database (KEGG, http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) and PANTHER ( http://www.pantherdb.org/pathway/). Enrichment statistics were adjusted by Benjamini correction.

Results

Weight

The weights of the offspring male mice are shown in Table 1. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). As determined using Student’s t-test, the famine group weighed less and the weights were significantly different from the control group (p < 0.05). During feeding, the famine group displayed the phenomena of mania and hyperactivity.

Table 1.

Mouse weights from the beginning of artificial feeding

|

Group |

Weight (g)/week |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Control |

8.69 ± 0.32 |

19.06 ± 0.85 |

21.57 ± 1.21 |

23.29 ± 1.08 |

24.53 ± 1.57 |

25.51 ± 2.02 |

26.04 ± 1.87 |

| Famine* | 8.69 ± 0.27 | 8.82 ± 0.77 | 10.28 ± 0.44 | 12.46 ± 0.50 | 13.32 ± 0.68 | 13.02 ± 0.94 | 11.45 ± 0.78 |

*P < 0.05, compared with the control group.

Total 5mc amount in the thalamus and hippocampus

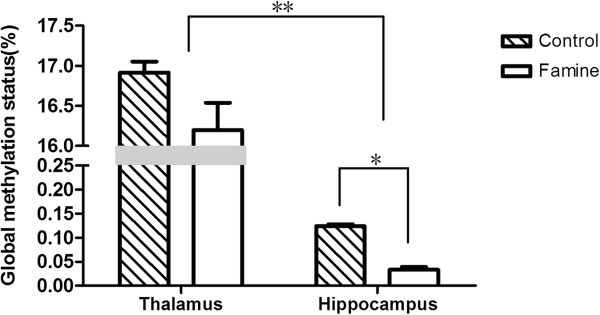

The global DNA methylation status in the thalamus and the hippocampus of postnatal malnourished mice and normal mice is shown in Figure 1. The global DNA methylation status in the thalamus was significantly higher than that of the hippocampus. In both the thalamus and the hippocampus, the control group had a higher total 5mc amount than the famine group.

Figure 1.

The global DNA methylation levels in the thalamus and hippocampus of postnatal malnourished mice and normal mice. Data are the mean ± s.e.m. *P = 0.046 (control group and famine group in the hippocampus, Student’s t-test). **P = 6.413e-05 (control group in the thalamus and hippocampus, Student’s t-test); 4.394e-04 (famine group in the thalamus and hippocampus, Student’s t-test).

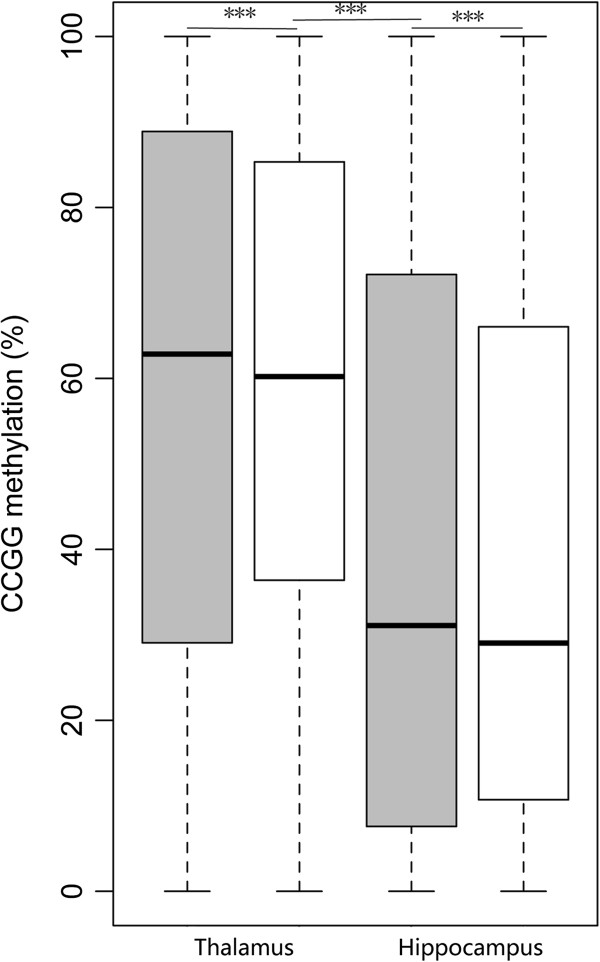

DNA methylome in the thalamus and hippocampus

The reads obtained from our libraries after MSCC whole genome methylation sequencing are shown in Table 2. After excluding MSCC sites with low sequencing depth, we obtained the DNA methylation profile of the thalamus (Additional file 2: Table S1) and the hippocampus (Additional file 3: Table S2). The overall methylation levels of all CCGG sites in the two tissues are shown in Figure 2. The CCGG methylation level of the hippocampus was also lower than that of the thalamus as the global DNA methylation status. The methylation differences between the famine and control groups or the thalamus and hippocampus were statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

MSCC Illumina sequencing statistics of the thalamus and hippocampus

| Library name | Number of reads with appropriate adaptors | Number of mapped reads (percentage) | Number of CCGG sites seen at least once | Average number of reads per CCGG site | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalamus |

Control-HpaII |

39239224 |

31413443 (80.0) |

1034841 |

30.4 |

| |

Control-Inverse |

35769649 |

20466887 (57.2) |

1118555 |

18.3 |

| |

Famine-HpaII |

57387236 |

46262199 (80.6) |

1076064 |

43 |

| |

Famine-Inverse |

46472846 |

27799576 (59.8) |

1175605 |

23.6 |

| Hippocampus |

Control-HpaII |

29639848 |

24301025 (81.2) |

1060634 |

22.9 |

| |

Control-Inverse |

26585724 |

15892801 (59.8) |

1136208 |

14.0 |

| |

Famine-HpaII |

37551216 |

30429853 (81.0) |

1125683 |

27.0 |

| Famine-Inverse | 42435514 | 25510407 (60.1) | 1191446 | 21.4 | |

Figure 2.

The overall methylation levels of all CCGG sites in the thalamus and hippocampus (control group in gray and famine group in white). The total methylation level at CCGG sites of the hippocampus was lower than that of the thalamus. ***P < 0.001 (control group and famine group in the thalamus and hippocampus, control group in the thalamus and hippocampus, famine group in the thalamus and hippocampus, Student’s t-test).

In addition, we also showed the methylation level in internal, shore and external CGIs of the thalamus and the hippocampus (Additional file 1: Figure S1a and S1b). In the two groups of both tissues, the level of methylation in the internal of the CpG islands was lower than that of the external of the CpG islands. Furthermore, the famine group had a lower methylation level than the control group at the external of the CpG islands, whereas it was hypermethylated in the internal of the CpG islands in both brain regions. The whole genome methylation pattern showed that the methylation level near the transcription initiation site (TSS) was lower than any other position (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

We combined the mouse thalamus gene expression data from the NCBI GEO database (GDS1490) with our MSCC thalamus data for the control group. First, we divided the database expression genes into three parts: high-expression genes, moderate-expression genes, and low-expression genes. Then, the MSCC data were integrated to the three parts of the expression genes. The relationship between the methylation level and gene expression is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S3a and S3b. The methylation level of the low-expression genes was higher at TSS but lower at the gene body than that of the high-expression genes.

There were 500 distinct genes in the thalamus (Additional file 4: Table S3) but none in the hippocampus, according to the results of the DMR analysis. Furthermore, all 500 selected genes obtained from the thalamus analysis of the famine group showed hypermethylation, and approximately 60% of the genes were associated with neuronal development and psychiatric diseases. The 20 crucial genes identified as being implicated in psychiatric diseases are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Twenty crucial genes related to psychiatric diseases among 500 selected genes of the thalamus

| Gene name | Related psychiatric diseases |

|---|---|

|

Slc18a2 |

Schizophrenia

[12], Alzheimer’s disease

[13], Parkinson’s disease

[14] |

|

Pi4k2b |

Bipolar disorder

[15] |

|

Prkacb |

Alzheimer’s disease

[16] |

|

Gabra1 |

Schizophrenia

[17] |

|

Bdnf |

Alzheimer’s disease

[18], Major depression disorder

[19] |

|

Katnb1 |

Bipolar disorder

[20] |

|

Psen1 |

Alzheimer’s disease

[21] |

|

Pde4a |

Schizophrenia

[22], Bipolar disorder

[23] |

|

Lrfn5 |

Autism

[24] |

|

Ppp3ca |

Alzheimer’s disease

[25,26] |

|

Shank3 |

Autism spectrum disorder

[27,28], Bipolar disorder

[29] |

|

Clu |

Alzheimer’s disease

[30,31] |

|

Notch4 |

Bipolar disorder

[32], Schizophrenia

[33] |

|

Sult4a1 |

Schizophrenia

[34] |

|

Rnf11 |

Parkinson’s disease

[35] |

|

Pclo |

Major depression disorder

[36], Bipolar disorder

[37] |

|

Tyro3 |

Alzheimer’s disease

[38] |

|

Calm2 |

Major depression disorder

[39] |

|

Cacna1c |

Schizophrenia

[40-42], Bipolar disorder

[43-45] |

| Plcb1 | Autism spectrum disorder [46], Schizophrenia [47] |

Properties of the hypermethylated genes

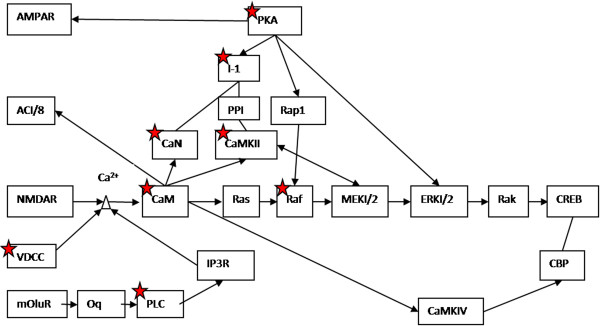

To gain mechanistic insights into the CpG modifications, we constructed our 500 gene set corresponding to biological pathways and networks underlying complex diseases using the online tool DAVID. In total, 20 pathways were matched with our gene sets, as shown in Table 4. The most highly enriched pathway, which remained significant after the adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing using the conservative Benjamini correction, was long-term potentiation (LTP, 5.3-fold enrichment, P = 0.033) with 9 relative genes from our study: Ppp1r1a, Ppp3r1, Raf1, Camk2b, Ppp3ca, Prkacb, Cacna1c, Plcb1, and Calm2 (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Twenty KEGG and PANTHER pathways applied to the 500 hypermethylated genes in the thalamus

|

Category |

Pathway |

Count |

Fold |

Benjamini |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment | P value | P value | |||

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Long-term potentiation |

9 |

5.270 |

2.58 × 10-4 |

0.033 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

MAPK signaling pathway |

16 |

2.475 |

0.002 |

0.108 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

Alzheimer disease-amyloid secretase pathway |

9 |

3.872 |

0.002 |

0.147 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Long-term depression |

7 |

3.985 |

0.008 |

0.283 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

GnRH signaling pathway |

8 |

3.380 |

0.009 |

0.250 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Calcium signaling pathway |

11 |

2.360 |

0.017 |

0.360 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Vascular smooth muscle contraction |

8 |

2.732 |

0.026 |

0.433 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Wnt signaling pathway |

9 |

2.476 |

0.028 |

0.405 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Melanogenesis |

7 |

2.869 |

0.034 |

0.428 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

TGF-beta signaling pathway |

10 |

2.080 |

0.046 |

0.876 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis |

8 |

2.411 |

0.046 |

0.496 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

Endogenous_cannabinoid_signaling |

4 |

4.832 |

0.047 |

0.757 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

PDGF signaling pathway |

11 |

1.930 |

0.052 |

0.698 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Glycerophospholipid metabolism |

5 |

3.059 |

0.078 |

0.654 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

Endothelin signaling pathway |

7 |

2.290 |

0.080 |

0.772 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

Notch signaling pathway |

5 |

2.963 |

0.084 |

0.727 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

Metabotropic glutamate receptor group II pathway |

5 |

2.908 |

0.088 |

0.691 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY |

Neurotrophin signaling pathway |

7 |

2.207 |

0.095 |

0.692 |

| PANTHER_PATHWAY |

Ionotropic glutamate receptor pathway |

5 |

2.804 |

0.098 |

0.682 |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | N-Glycan biosynthesis | 4 | 3.564 | 0.100 | 0.679 |

Figure 3.

The 9 relative genes marked with red stars: Ppp1r1a (I-1), Ppp3r1 (CaN), Raf1 (Raf), Camk2b (CaMKII), Ppp3ca (CaN), Prkacb (PKA), Cacna1c (VDCC), Plcb1 (PLC), and Calm2 (CaM) in the most significant identified pathway, i.e., long-term potentiation.

Discussion

In contrast to previous studies that focused mainly on the influence of maternal malnutrition on fetal neurodevelopment [1-3], [10], our study provides a striking view of how the epigenetic DNA methylation landscape of the thalamus and the hippocampus in postnatal individuals is modified in response to malnourishment. We describe a genome-wide, quantitative characterization of malnourishment-induced CpG methylation changes in postnatal mice. These data may serve as a useful resource for the neuroscience community and brain science studies.

Our study demonstrated several key aspects of malnourishment-induced epigenetic DNA modifications in mice. First, the global DNA methylation status in the thalamus and the hippocampus of postnatal malnourished mice and normal mice had significant differences. This told us that the mechanism of the malnourishment-induced epigenetic DNA modifications in the thalamus was different from the hippocampus. Second, our analysis revealed specific characteristics of the genomic DNA methylation distribution in the thalamus and the hippocampus of malnourished mice and normal mice. Third, our MSCC results provided direct profiling regarding the malnourishment-induced DNA methylation changes in both the thalamus and the hippocampus. Fourth, our study provided a large number of genes that were subjected to modulation by malnourishment at the level of DNA modification. The majority of these genes were associated with neuronal occurrence and development.

CpG-rich regions of DNA are known as CpG islands (CGIs), and most CGIs remain unmethylated [48]. Moreover, approximately 60% of mammalian genes have CGI promoters, and methylated CGIs play an important role in gene silencing during processing [49]. The best-known producer of epigenesis, DNA methylation, plays an important role in regulating gene expression to preserve local activity states [50]. Epigenesis is defined as heritable changes in gene expression that are not accompanied by changes in DNA sequence [51]. Thus, to reflect the DNA methylation landscape and distribution, we measured the methylation level in different regions of the genome. To gain more insight into whether the changes caused by methylation were present on the gene expression level, we performed comparisons between our MSCC data and the gene expression data (GDS1490). All our results were in accordance with the theoretical basic characteristics of DNA methylation modification in mammals, which confirmed the accuracy of our experiment.

It should be noted that when we used our criteria (∆MSCC > 25%) to screen out differential genes in the normal and famine groups, no genes were selected in the hippocampus, while 500 distinct genes were revealed in the thalamus. This may due to the selected CCGG methylated level in the hippocampus, which was much lower than that in the thalamus. Thus, a methylation level of >25% was difficult to achieve in the hippocampus. In this regard, further study of the hippocampus, which has vital roles in brain development, cognition, learning, and memory [52], would provide valuable information.

In the thalamus, the most significant identified relative pathway was long-term potentiation. It is a major form of long-lasting synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain, which occurs by increasing synaptic strength, and is involved in information storage, and therefore, in learning and memory [53]. Ppp1r1a, Ppp3r1, Raf1, Camk2b, Ppp3ca, Prkacb, Cacna1c, Plcb1, and Calm2 were the filtered genes in this pathway from our study. These genes are critically involved in neuronal formation and development. Among the 9 genes, Camk2b plays important roles in brain synaptic plasticity [54]. Ppp3ca is a tumor suppressor gene that functions in Alzheimer’s disease [25,26]. Prkacb is a protein kinase and is related to Alzheimer’s disease [16]. Plcb1 is of critical importance in codifying neurotransmitter receptors and is associated with schizophrenia [46,47]. It is particularly noteworthy that the calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L-type, alpha 1C subunit (Cacna1c) gene contributes to many psychiatric disorders [55,56], specifically schizophrenia [40-42] and bipolar disorder [43-45].

Our study considered the global DNA methylation status of the thalamus and the hippocampus and provides a DNA methylation landscape of these two brain regions after they were modified by malnutrition. It also implicates DNA modification as an effective epigenetic regulator in postnatal brain maturation. Our data also indicate that malnutrition in postnatal individuals may increase the risk of developing psychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nonetheless, we believe that much more research on the functional verification of the related genes is necessary to obtain a better understanding of the pathogenesis of malnutrition.

Conclusions

In this study, the thalamus and the hippocampus had different global DNA methylation statuses in postnatal malnourished mice and normal mice. Discriminable variations related to neuronal development and psychiatric disorders were also observed in the thalamus. Pathway analyses of the corresponding genes highlighted changes for 9 genes related to long-term potentiation (5.3-fold enrichment, P = 0.033). Our findings may help to differentiate the genome-wide DNA methylation status of different brain regions, and the results also indicate that postnatal malnutrition may increase the risk of psychiatric disorders.

Abbreviations

5mC: 5-methylcytosine; NGS: Next-generation sequencing; MSCC: Methyl-sensitive cut counting; SLAC: Shanghai Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd; RFU: Relative fluorescence units; DMRs: Different methylated regions; ∆MSCC: Different levels of methylation changes; SD: Standard deviation; TSS: Transcription initiation site; LTP: Long-term potentiation; CGIs: CpG islands; Cacna1c: Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, L-type, alpha 1C subunit gene.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LH and YL supervised the experiment. DZZ and FTL designed the experimental protocol. XLW and FTL carried out the experiment. YL, XLW, DZZ, FTL, HZ, JYY, ZZ, DZ, YNW, LMT, LC, MYK, TW, GYF, XLQ, and JHS analyzed and discussed the experimental results. Finally, XLW, YL, and FTL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials.

MSCC results of the thalamus for all MSCC 30+ sites.

MSCC results of the hippocampus for all MSCC 30+ sites.

Selected 500 distinctive genes in the thalamus.

Contributor Information

Xiaoling Weng, Email: wengxlchn@gmail.com.

Daizhan Zhou, Email: zhoudaizhan@gmail.com.

Fatao Liu, Email: fasterliu2010@gmail.com.

Hong Zhang, Email: mingyi-hong@163.com.

Junyi Ye, Email: qualoc@126.com.

Zhou Zhang, Email: zhangzhoua@gmail.com.

Di Zhang, Email: aureliano.jz@gmail.com.

Yinan Wang, Email: yinan.wang.yn@gmail.com.

Liming Tao, Email: taoliming.too@gmail.com.

Lan Cao, Email: caolan04@gmail.com.

Mengyuan Kan, Email: mengyuankan@gmail.com.

Ting Wang, Email: wangting0607@gmail.com.

Guoyin Feng, Email: mssun@sibcb.ac.cn.

Xiaolan Qin, Email: qxlssc@163.com.

Jihui Sun, Email: bullets_333cn@163.com.

Lin He, Email: helin@bio-x.cn.

Yun Liu, Email: superliuyun@gmail.com.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Program on Key Basic Research Project of China (973 Program, 2011CB504000), the National Key Technology R&D Program (2012BAI01B09), the Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.67001118), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81121001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31200954), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation-funded projects (2012 M510110, 2013 T60440).

References

- Alamy M, Bengelloun WA. Malnutrition and brain development: an analysis of the effects of inadequate diet during different stages of life in rat. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;15(6):1463–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgane PJ, Austin-LaFrance R, Bronzino J, Tonkiss J, Diaz-Cintra S, Cintra L, Kemper T, Galler JR. Prenatal malnutrition and development of the brain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1993;15(1):91–128. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(05)80234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;15(9608):243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman Y, Cedar H. DNA methylation dynamics in health and disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;15(3):274–281. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M, Hellmann I, Stadler MB, Ramos L, Paabo S, Rebhan M, Schubeler D. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;15(4):457–466. doi: 10.1038/ng1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, Jaaro-Peled H, Tankou S, Seshadri S, Hikida T, Matsumoto Y, Cascella NG, Kano S, Ozaki N, Nabeshima T, Sawa A. Adolescent stress-induced epigenetic control of dopaminergic neurons via glucocorticoids. Science. 2013;15(6117):335–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1226931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MP, Li JB, Gao Y, Lee JH, LeProust EM, Park IH, Xie B, Daley GQ, Church GM. Targeted and genome-scale strategies reveal gene-body methylation signatures in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;15(4):361–368. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Ma DK, Mo H, Ball MP, Jang MH, Bonaguidi MA, Balazer JA, Eaves HL, Xie B, Ford E, Zhang K, Ming GL, Gao Y, Song H. Neuronal activity modifies the DNA methylation landscape in the adult brain. Nature neuroscience. 2011;15(10):1345–1351. doi: 10.1038/nn.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabory A, Attig L, Junien C. Developmental programming and epigenetics. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;15(6 Suppl):1943S–1952S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.000927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Li X, Qiu Y, Su M, Liu Y, Li H, Wang X, Zou X, Yan C, Yu L, Li S, Wan C, He L, Jia W. Metabonomic and metallomic profiling in the amniotic fluid of malnourished pregnant rats. Journal of proteome research. 2008;15(5):2151–2157. doi: 10.1021/pr700776c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;15(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;15(7):484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;15(1):6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;15(6):465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R. The inheritance of epigenetic defects. Science. 1987;15(4824):163–170. doi: 10.1126/science.3310230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;15(9):700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H, Barth AL, Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. A developmental switch in the signaling cascades for LTP induction. Nat Neurosci. 2003;15(1):15–16. doi: 10.1038/nn985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgesius NZ, van Woerden GM, Buitendijk GH, Keijzer N, Jaarsma D, Hoogenraad CC, Elgersma Y. betaCaMKII plays a nonenzymatic role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning by targeting alphaCaMKII to synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;15(28):10141–10148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5105-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiocco MJ, Zhu X, Walther D, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Uhl GR, Liu QR. Fine mapping of calcineurin (PPP3CA) gene reveals novel alternative splicing patterns, association of 5′UTR trinucleotide repeat with addiction vulnerability, and differential isoform expression in Alzheimer’s disease. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;15(11):1809–1826. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloret A, Badia MC, Giraldo E, Ermak G, Alonso MD, Pallardo FV, Davies KJ, Vina J. Amyloid-beta toxicity and tau hyperphosphorylation are linked via RCAN1 in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;15(4):701–709. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Higuera JL, Mateo I, Sanchez-Juan P, Rodriguez-Rodriguez E, Pozueta A, Calero M, Dobato JL, Frank-Garcia A, Valdivieso F, Berciano J, Bullido MJ, Combarros O. Genetic variation in the tau kinases pathway may modify the risk and age at onset of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2011;15(2):291–297. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girirajan S, Dennis MY, Baker C, Malig M, Coe BP, Campbell CD, Mark K, Vu TH, Alkan C, Cheng Z, Biesecker LG, Bernier R, Eichler EE. Refinement and discovery of new hotspots of copy-number variation associated with autism spectrum disorder. American journal of human genetics. 2013;15(2):221–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Vasco VR, Cardinale G, Polonia P. Deletion of PLCB1 gene in schizophrenia-affected patients. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;15(4):844–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskvina V, Craddock N, Holmans P, Nikolov I, Pahwa JS, Green E, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC. Gene-wide analyses of genome-wide association data sets: evidence for multiple common risk alleles for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and for overlap in genetic risk. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;15(3):252–260. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoller JW, Craddock N, Kendler K, Lee PH, Neale BM, Nurnberger JI, Ripke S, Santangelo S, Sullivan PF. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;15(9875):1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-Wide Association Study C. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat Genet. 2011;15(10):969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamshere ML, Walters JT, Smith R, Richards AL, Green E, Grozeva D, Jones I, Forty L, Jones L, Gordon-Smith K, Riley B, O'Neill FA, Kendler KS, Sklar P, Purcell S, Kranz J, Morris D, Gill M, Holmans P, Craddock N, Corvin A, Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC. Schizophrenia Psychiatric Genome-wide Association Study Consortium. Genome-wide significant associations in schizophrenia to ITIH3/4, CACNA1C and SDCCAG8, and extensive replication of associations reported by the Schizophrenia PGC. Molecular psychiatry. 2013;15(6):708–712. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyegaard M, Demontis D, Foldager L, Hedemand A, Flint TJ, Sorensen KM, Andersen PS, Nordentoft M, Werge T, Pedersen CB, Hougaard DM, Mortensen PB, Mors O, Borglum AD. CACNA1C (rs1006737) is associated with schizophrenia. Molecular psychiatry. 2010;15(2):119–121. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira MA, O'Donovan MC, Meng YA, Jones IR, Ruderfer DM, Jones L, Fan J, Kirov G, Perlis RH, Green EK, Smoller JW, Grozeva D, Stone J, Nikolov I, Chambert K, Hamshere ML, Nimgaonkar VL, Moskvina V, Thase ME, Caesar S, Sachs GS, Franklin J, Gordon-Smith K, Ardlie KG, Gabriel SB, Fraser C, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Breen G, Gill M. et al. Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nature genetics. 2008;15(9):1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/ng.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar P, Smoller JW, Fan J, Ferreira MA, Perlis RH, Chambert K, Nimgaonkar VL, McQueen MB, Faraone SV, Kirby A, de Bakker PI, Ogdie MN, Thase ME, Sachs GS, Todd-Brown K, Gabriel SB, Sougnez C, Gates C, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Ardlie KG, Franklin J, Muir WJ, McGhee KA, MacIntyre DJ, McLean A, VanBeck M, McQuillin A, Bass NJ, Robinson M. et al. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Molecular psychiatry. 2008;15(6):558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogia J, Ruberto G, Lelli-Chiesa G, Vassos E, Maieru M, Tatarelli R, Girardi P, Collier D, Frangou S. The impact of the CACNA1C gene polymorphism on frontolimbic function in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;15(11):1070–1071. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons CJ, van Winkel R. Intermediate Phenotype Analysis of Patients, Unaffected Siblings, and Healthy Controls Identifies VMAT2 as a Candidate Gene for Psychotic Disorder and Neurocognition. Schizophr bulletin. 2013;15(4):848–856. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, Okamura N, Pejoska S, Drago J, Mulligan RS, Chetelat G, Ackermann U, O'Keefe G, Jones G, Gong S, Tochon-Danguy H, Kung HF, Masters CL, Skovronsky DM, Rowe CC. In vivo assessment of vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 in dementia with lewy bodies and Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology. 2011;15(7):905–912. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotagal V, Albin RL, Muller ML, Koeppe RA, Chervin RD, Frey KA, Bohnen NI. Symptoms of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are associated with cholinergic denervation in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;15(4):560–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.22691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan LM, Christoforou A, Arbuckle MI, Torrance HS, Anderson SM, Muir WJ, Porteous DJ, Blackwood DH, Evans KL. A case–control association study and family-based expression analysis of the bipolar disorder candidate gene PI4K2B. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;15(16):1272–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pun FW, Zhao C, Lo WS, Ng SK, Tsang SY, Nimgaonkar V, Chung WS, Ungvari GS, Xue H. Imprinting in the schizophrenia candidate gene GABRB2 encoding GABA(A) receptor beta(2) subunit. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;15(5):557–568. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang PJ, Li MH, Gao XL, Gu GJ, Shao ZH. 1H-MRS can monitor metabolites changes of lateral intraventricular BDNF infusion into a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease in vivo. Neuroscience. 2013;15:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar E, Shams J, Sabetkasaei M, MS M, Rashidkhani B, Mostafavi A, Bornak E, Nasrollahzadeh J. Effects of zinc supplementation on efficacy of antidepressant therapy, inflammatory cytokines, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with major depression. Nutr Neurosci. 2014;15(2):65–71. doi: 10.1179/1476830513Y.0000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatani N, Hattori E, Ohnishi T, Dean B, Iwayama Y, Matsumoto I, Kato T, Osumi N, Higuchi T, Niwa S, Yoshikawa T. Genome-wide expression analysis detects eight genes with robust alterations specific to bipolar I disorder: relevance to neuronal network perturbation. Human molecular genetics. 2006;15(12):1949–1962. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Winter P, Graeber MB. A presenilin 1 mutation in the first case of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;15(2):129–130. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Takaki H, Wang L, Kuroki T, Nakahara T, Hashimoto K, Ninomiya H, Arinami T, Inada T, Ujike H, Itokawa M, Tochigi M, Watanabe Y, Someya T, Kunugi H, Iwata N, Ozaki N, Shibata H, Fukumaki Y. Positive association of phencyclidine-responsive genes, PDE4A and PLAT, with schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;15(7):850–858. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi SH, Reutiman TJ, Folsom TD, Lee S. Phosphodiesterase-4A expression is reduced in cerebella of patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2008;15(6):282–288. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e3283060fb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhail FM, Lose EJ, Robin NH, Descartes MD, Rutledge KD, Rutledge SL, Korf BR, Carroll AJ. Clinically relevant single gene or intragenic deletions encompassing critical neurodevelopmental genes in patients with developmental delay, mental retardation, and/or autism spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;15(10):2386–2396. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangash MA, Park JM, Melnikova T, Wang D, Jeon SK, Lee D, Syeda S, Kim J, Kouser M, Schwartz J, Cui Y, Zhao X, Speed HE, Kee SE, Tu JC, Hu J, Petralia RS, Linden DJ, Powell CM, Savonenko A, Xiao B, Worley PF. Retraction notice to: Enhancedpolyubiquitination of Shank3 and NMDA receptor in a mouse model of autism. Cell. 2013;15(1-2):367. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert MR. SHANK3, the synapse, and autism. N Engl J Med. 2011;15(2):173–175. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1104261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denayer A, Van Esch H, de Ravel T, Frijns JP, Van Buggenhout G, Vogels A, Devriendt K, Geutjens J, Thiry P, Swillen A. Neuropsychopathology in 7 Patients with the 22q13 Deletion Syndrome: Presence of Bipolar Disorder and Progressive Loss of Skills. Molecular syndromology. 2012;15(1):14–20. doi: 10.1159/000339119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Yu JT, Zhang W, Wu ZC, Zhang Q, Liu QY, Wang W, Wang HF, Ma XY, Cui WZ. Association of GWAS-linked loci with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a northern Han Chinese population. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;15(5):546–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JT, Ma XY, Wang YL, Sun L, Tan L, Hu N, Tan L. Genetic variation in Clusterin gene and Alzheimer’s disease risk in Han Chinese. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;15(7):1921. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.01.010. e1917-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieset I, Djurovic S, Tesli M, Hope S, Mattingsdal M, Michelsen A, Joa I, Larsen TK, Agartz I, Melle I, Rossberg JI, Aukrust P, Andreassen OA, Ueland T. Up-regulation of NOTCH4 gene expression in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;15(12):1292–1300. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayevitz C, Cohen OS, Faraone SV, Glatt SJ. A re-review of the association between the NOTCH4 locus and schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;15(5):477–483. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Brennan MD, Woodward ND, Jayathilake K. Association of Sult4A1 SNPs with psychopathology and cognition in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2008;15(2–3):258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LR, Betarbet R, Gearing M, Gulcher J, Hicks AA, Stefansson K, Lah JJ, Levey AI. PARK10 candidate RNF11 is expressed by vulnerable neurons and localizes to Lewy bodies in Parkinson disease brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;15(10):955–964. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3181567f17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, de Geus EJ, Willemsen G, James MR, Smit JH, Zandbelt T, Arolt V, Baune BT, Blackwood D, Cichon S, Coventry WL, Domschke K, Farmer A, Fava M, Gordon SD, He Q, Heath AC, Heutink P, Holsboer F, Hoogendijk WJ, Hottenga JJ, Hu Y, Kohli M, Lin D, Lucae S, Macintyre DJ, Maier W, McGhee KA, McGuffin P, Montgomery GW. et al. Genome-wide association for major depressive disorder: a possible role for the presynaptic protein piccolo. Molecular psychiatry. 2009;15(4):359–375. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Higgs BW, Wendland JR, Song J, McMahon FJ, Webster MJ. Gene expression and genetic variation data implicate PCLO in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;15(4):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Wang Q, Xiao B, Lu Q, Wang Y, Wang X. Involvement of receptor tyrosine kinase Tyro3 in amyloidogenic APP processing and beta-amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease models. PLoS One. 2012;15(6):e39035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Voleti B, Hajszan T, Rajkowska G, Stockmeier CA, Licznerski P, Lepack A, Majik MS, Jeong LS, Banasr M, Son H, Duman RS. Decreased expression of synapse-related genes and loss of synapses in major depressive disorder. Nature medicine. 2012;15(9):1413–1417. doi: 10.1038/nm.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials.

MSCC results of the thalamus for all MSCC 30+ sites.

MSCC results of the hippocampus for all MSCC 30+ sites.

Selected 500 distinctive genes in the thalamus.