Abstract

Background

Probiotics are supplements or foods that contain viable microorganisms which cause alterations of the microflora of the host. Probiotics have already been established in the treatment and prevention of various gastrointestinal system. Recently, role of probiotics has become an important issue for research in dentistry in the era of increased antibiotic resistance.

Materials and methods

The basis of the paper is the clinical studies and research done in relation to probiotics on oral health using PUBMED search database.

Results and conclusions

Although many clinical studies have demonstrated positive outcome in preventing caries and periodontal diseases, the data is still scarce in recommending probiotics for the oral health. Moreover, since initial colonization of oral cavity of the newborn is very important for developing immunity and prevention of future diseases. Hence, measures should be directed towards its preventive use in infants and children. The formulations produced for oral cavity should also be within reach of common man especially in underdeveloped and developing countries. This review endeavors to compile the research of probiotics on oral cavity and throws a light on its evolving status in developing countries. It also evaluates its use in children for a long-term benefit.

Keywords: Probiotics, Streptococcus mutans, Dental caries, Children

Introduction

The term probiotic was derived from the Greek word, meaning “for life”. An expert panel commissioned by FAO and WHO defined probiotics as “Live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host”.1

The use of probiotics in medical practice is evolving because of surging levels of multidrug resistance among pathogenic organisms and the increasing demands of consumers for natural substitutes for drugs.2 Traditionally, probiotics were developed to alter Gut microflora. As oral cavity forms the first part of GIT, it is conceivable for probiotics to influence the oral microflora. The oral cavity consists of a complex system of diverse microbiota and using this concept of altering microbial ecological balance from a pathogenic to a non-pathogenic system is a novel approach.

The aim of this review is to evaluate and compile the researches done on probiotics especially in relation to oral health of children and to discuss its present scenario and outreach in a developing country like India.

Materials and methods

The basis of the paper is the clinical studies and research done on the relation of probiotics on oral health. A search on PUBMED database was conducted based on the search items “probiotics”, “probiotics and oral cavity”, “lactobacilli”, “bifidobateria”, “salivary bacteria”, “probiotics in pediatrics” and “caries prevention”. As of April 2012, probiotics revealed as high as 7319 papers and its oral health relation reveals 89 searches. Relevant papers were identified after a review of abstracts.

Probiotics

Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species are the most commonly used probiotics. These bacteria are found in fermented dairy products and colonize gastrointestinal tract soon after birth.3,4 Many health benefits of probiotic usage on various systems of the body have been documented in literature. However, these are beyond the scope of discussion of this paper.

The oral cavity is a very intricately balanced homeostatic chamber. The moment the defenses of the body get lowered, the opportunistic bacteria take over and start affecting the various hard and soft tissues of the mouth. Though dental caries is multifactorial in origin, the most commonly involved organism are Streptococcus mutans as the initiators and Lactobacilli as the secondary invaders. The process of the tooth decay ensues by the progression of adhesion, co-aggregation and secondary colonization.

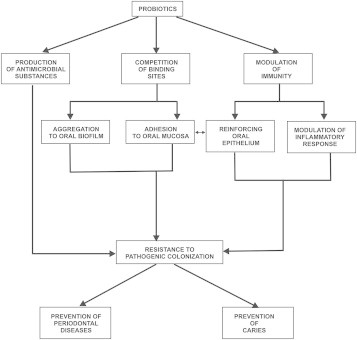

A lot of studies documented in the literature explore the mechanism of probiotic in gut but its action in oral cavity has not been well understood. Since, the oral cavity forms the main entry to gut there is a possibility of interaction of probiotic with environmental factors of the mouth. An outline of its possible mechanism of action is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Possible mechanism of action of probiotics in oral cavity.

It is necessary for the probiotics to remain viable and adhere to the oral cavity for them to take time to act. There are a lot of substances such as salivary proteins, lysozyme, lactoferrins, secretory IgA etc that can affect the viability of the cell surface morphology of the probiotic species in the oral cavity. The biofilms are important mediators which encourage adhesion. In-vitro studies have assessed adhesion by measuring the attachment of bacteria to saliva-coated hydroxyapatite (HA) and oral epithelium.5 Among probiotics strains Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG exhibited the highest values of adhesion, comparable to those of the early tooth colonizer Streptococcus sanguinis.6

Dental caries

Several clinical studies report effect of probiotics in reducing the development of caries. Table 1. Most commonly used probiotics are acidogenic and have the capability to dissolve hard structures like enamel and dentine.7 However, it has been shown that only few strains of Lactobacilli participate in caries and its progression than invasion.8 Only three of the 50 strains of lactobacilli isolated from school going children induced caries in hamsters.9 Among 32 lactobacillus species, 17 were moderately cariogenic in rats.10 Only five species out of 3790 expressed inhibitory effect against other microorganisms, including oral Candida11 as the antimicrobial potential of the bacteria was affected by several factors, such as pH, catalase, proteolytic enzymes, ad temperature. Lactobacillus paracasei and L. rhamnosus strains exhibited antimicrobial activity. Subjects without caries are colonized by Lactobacilli, which possess a significantly increased capacity to suppress growth of mutans streptococci compared to subjects with arrested or active caries.12

Table 1.

List of clinical studies done in oral cavity with probiotics.

| Oral diseases | Probiotic | Vehicle of administration | Duration of study | No./Age group/type of study | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental caries | L. rhamnosus GG | Cheese | 3 weeks | 74/18–35 years/RCT, DB | - Reduction of S. mutans - Reduction of yeast |

Ahola et al., 2002 |

| L. rhamnosus GG | Milk | 7 months | 594/1–6 years/RCT, DB | - Reduction S. mutans - Reduction of caries |

Nase et al., 2001 | |

| Bifidobacterium DN-173010 | Yogurt | 4 weeks | 26/21–24 years/RCT, crossover | Reduction of S. mutans | Caglar et al., 2005 | |

| B. animalis sub sp. Lactis DN-173010 | Fruit yogurt | 4 weeks | 24/12–16 years/RCT, DB | Reduction of S. mutans | Cildir et al., 2009 | |

| L. reuteri | Yogurt | 2 weeks | 40/20 years/RCT crossover | Reduction of S. mutans | Nikawa et al., 2004 | |

| Lactobacilli spp. | Liquid capsules placebo | 45 days | 35/24–33 years/RCT, DB | - Increase of Lactobacilli – No. change of S. mutans | Montalto et al., 2004 | |

| L. reuteri | Water straw lozenges/placebo | 3 weeks | 120/21–24 years/RCT, DB | Reduction of S. mutans | Caglar et al., 2006 | |

| L. reuteri | Lozenges via medical device | 10 days | 10/20 years/RCT, DB | Reduction of S. mutans | Caglar et al., 2007 | |

| L. bulgaricus | Yogurt, ice-cream | 3 weeks | 44/23–37 years/RCT | Reduction of S. mutans | Petti et al., 2001 | |

| Yeast infection | L. rhamnosus | Cheese | 16 weeks | 294/70–100 years RCT, DB | Reduction of candida | Hatakka et al., 2005 |

| Gingivitis | L. reuteri | Gum | 2 weeks | 58/adults RCT, DB | Reduction of gingivitis | Krasse et al., 2006 |

An in-vitro study was the first to state that Lactobacillus acidophilus could inhibit growth of other bacteria.13 Lactobacillus species strain GG could produce different antimicrobial components such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, carbon peroxide, diacetyl, low molecular weight antimicrobial substances, bacteriocins, and adhesion inhibitors against Streptococcus,14 hence could be used as a potent probiotic.

L. rhamnosus strains LGG (ATCC 53103) have demonstrated inhibitory effect on the growth of Streptococcus sobrinus in an agar overlay technique. The L. rhamnosus strains, L. paracasei F19 and Lactobacillus reuteri do not ferment sucrose and are relatively safe probiotic strains in caries-prophylactic perspective.15–17

Effect of L. rhamnosus on level of S. mutans was studied in rats18 to find if yoghurt containing probiotics have a significant effect on decreasing the percentage of cariogenic bacteria and yeast. Modulation of oral toleration of beta-lactoglobulin BLG by probiotics was reported in gnotobiotic mice.19

Heat killed lactic bacteria with pyridoxine lead to 42% reduction in the incidence of dental caries at 2-year follow-up.20 Administration of probiotic (LGG) to kindergarten children (1–6-year old) resulted in reduction of mutans streptococci counts, caries risk and initial caries development. The effect was particularly more for the 3–4-year olds.21 This might be attributed to “window of infectivity” in children.

Evaluation of a suitable vehicle for probiotic administration is an essential. Most of the naturally occurring probiotics are found in fermented dairy products. Milk acts as a buffer to the acid produced.22 Milk itself contains calcium, calcium lactate and other organic and inorganic compounds that are anticariogenic23,24 and reduce the colonization of pathogens.25

Nase et al21 used milk, Ahola et al26 administered cheese with a combination of LGG and L. rhamnosus LC 705 for 3 weeks. Cheese was thought to have more local effect as it cleared more slowly from mouth than milk. Mutans counts decreased in 20% and yeast counts in 27% of all the subjects, in both the groups.

Montalto et al27 found non-dairy products and orally administered seven live Lactobacilli in capsules and liquid form, to produce similar effects. Çaglar et al28 administered L. reuteri ATCC 5573029 in capsule and straw forms in young adults for 3 weeks, and raised the possibility of a systemic effect along with local effect. Daily chewing of gums containing probiotic bacteria or xylitol reduced the levels of salivary MS in a significant way.30 However, a combination of probiotic and xylitol gums did not seem to enhance this effect. Keeping infants in mind, Cagler et al31 developed a pacifier like sucking device for probiotic lozenges containing L. Reuteri ATCC 55730/L. Reuteri ATCC PTA 5289 (1.1 × 108 CFU). Ice-cream containing Bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12 or Lactobacilli bulgaricus have been reported32,33 where both resulted in reduction of S. mutans. Next to Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria are probiotics commonly used for improving the intestinal microbial balance.34

Yli-Knutilla35 studied the colonization of L. rhamnosus GG in oral cavity in a 14-day trial period and observed that it was detected only temporarily, for up to 1 week after discontinuation of the fruit juice. In one female subject, however, whose medical history revealed use of L. rhamnosus GG in childhood, the bacterium was detected in all saliva samples taken upto 5 months after discontinuation of the fruit juice.

Effect on oral cavity

It has been suggested that adequate establishment of the intestinal flora after birth plays a crucial role in the development of the innate and adaptive immune system.36 The newborn infant's gestational age, mode of delivery and diet seem to have significant effects on this process. Neonates who are born by Caesarian delivery, preterm, exposed to perinatal or postnatal antibiotics show a delay in intestinal commensal probiotic bacterial colonization. Breastfed infants are found to have Bifidobacteria-predominant colonization, whereas formula-fed infants have equal colonization with Bacteroides and Bifidobacteria species.37–39 Probiotic bacteria, postbiotic bacterial byproducts, and dietary prebiotics are believed to exert positive effects on the development of the mucosal immune system. The ingested human milk containing the bacterial components derived from the mother are thought to influence her young infant's developing immune system. This process is termed “bacterial imprinting”.40

Similarly, oral cavity is colonized with microorganism soon after birth and may form the indigenous microflora that may persist for life and prevent growth of other bacteria.41,42 Bacteria that subsequently attempt to colonize must compete with other microorganisms for colonization sites and essential nutrients. Additionally, they must survive in the presence of adverse metabolic end-products and antimicrobial products that may be produced by other members of the indigenous oral biota. Once established, early-colonizing species tend to persist in the mouth.41 As it has been demonstrated that vaginally born children are colonized by cariogenic bacteria later in life as they are exposed to more maternal and environmental bacteria at birth than via caesarean section which may be the result of competition between Lactobacilli and Streptococci.42

This can be deducted from the above discussion that if non-cariogenic bacteria colonize the oral cavity in early life, this might prove a long-term effect. Only one of the clinical studies documented has been performed on children.21 There exists a need of more long-term clinical research to demonstrate probiotics effects in infants.43

Status of probiotics in India

Extensive researches have been carried in countries with advanced technologies dedicated single-mindedly to the field of health sciences. The Indian subcontinent is altogether a different story. India is a developing country where about 75% of country's population still depends on agriculture as the primary source of income and resides in villages. Thus what we have is an ignorant and illiterate population for whom oral hygiene and dental problems are of no importance. Most of the children are devoid of basic health care facilities. This exposes the people to inadvertent use of antibiotics raising the problems of antibiotic resistance. Any approach to improve health should be directed towards prevention than cure. Also the dental clinicians tend to cluster in urban areas, leading to lack of awareness in rural areas. Hence, the concept of probiotics introduction to the general population would seem surreal. To make this theoretical possibility a fact, we need an inexpensive form of probiotics made readily available.

Ice-creams and probiotic curds can be made easily available and are quite frequently used items in the Indian households. Although the most common form of probiotic, yogurt (Dahi – L. bulgaricus + Lactobacilli thermophillus) is a regular component of diet in most of the Indian homes, awareness needs to be established for its effect in oral cavity. Moreover, even in the urban parts of India, probiotics are available for gastrointestinal health, none of the form is been formulated for oral health. The most commonly available probiotic preparations are supplied in capsules, enteric coated formulations, freeze dried preparations or in combination with antibiotics and vitamins. Some companies have approached Indian markets with dairy formulations of probiotics but they are not available easily in all parts of India. For oral cavity, specific preparations with different strains in lozenges, chewing gums or mouthwashes should be prepared which would allow a long-term contact with oral cavity and produce better results.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that probiotics have a definite role in the prevention of dental diseases especially caries. Undoubtedly, this appears to be a novel and effective approach in the developing era of increasing antibiotic resistance. The early colonization if developed at an early age can prevent caries thus important for pediatric dentistry.

Before establishing it as an effective preventive measure, few doubts which need to be cleared are to find the best strain of probiotic in oral cavity, dosage and schedule of probiotic intake, safety of long-term probiotics in oral cavity, most effective mode of delivery of probiotics and the duration of its contact in the oral cavity, cost effectiveness and easy availability, for which long-term longitudinal studies are required.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Teughels W., Van essche M., Sliepen I., Quirynen M. Probiotics and oral healthcare. Periodontol. 2000;2008(48):111–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid G., Jass J., Sebulsky M.T., McCormick J.K. Potential uses of probiotics in clinical practice. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(4):658–672. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.4.658-672.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamatova I., Meurman J.H. Probiotics: health benefits in the mouth. Am J Dent. 2009;22:329–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. 2002, posting date. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization Working Group Report. (Online).

- 5.Stamatova I., Kari K., Vladimirov S., Meurman J.H. In vitro evaluation of yoghurt starter Lactobacilli and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG adhesion to saliva-coated surfaces. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2009;24:218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2008.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilliland S.E., Kim H.S. Effect of viable starter culture bacteria in yogurt on lactose utilization in humans. J Dairy Sci. 1984;67:1–6. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(84)81260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toi C.S., Mogodiri R., Cleaton-Jones P.E. Mutans streptococci and Lactobacilli on healthy and carious teeth in the same mouth of children with and without dental cariës. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2000;12:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maltz M., de Oliveira E.F., Fontanella V., Bianchi R. A clinical, microbiologic, and radiographic study of deep caries lesions after incomplete caries removal. Quintessence Int. 2002;33:151–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald R.J., Fitzgerald D.B., Adams B.O., Duany L.F. Cariogenicity of human oral Lactobacilli in hamsters. J Dent Res. 1980;59:832–837. doi: 10.1177/00220345800590051501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgerald R.J., Adams B.O., Fitzgerald D.B., Knox K.W. Cariogenicity of human plaque Lactobacilli in gnotobiotic rats. J Dent Res. 1981;60:919–926. doi: 10.1177/00220345810600051201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokhee S., Chulasiri M., Prachyabrued W. Lactic acid bacteria from healthy oral cavity of Thai volunteers: inhibition of oral pathogens. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;90:172–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simark-Mattsson C., Emilson C.G., Håkansson E.G., Jacobsson C., Roos K., Holm S. Lactobacillus-mediated interference of mutans streptococci in caries-free vs. caries-active subjects. Eur J Oral Sci. 2007;115(4):308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polonskaia M.S. Antibiotic substances in acidophil bacteria. Mikrobiologiia. 1952;21:303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva M., Jacobus N.V., Deneke C., Gorbach S.L. Antimicrobial substance from a human Lactobacillus strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1231–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.8.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meurman J.H., Antila H., Korhonen A., Salminen S. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (ATCC 53103) on the growth of Streptococcus sobrinus in vitro. Eur J Oral Sci. 1994;103:253–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedberg M., Hasslof P., Sjöström I., Twetman S., Stecksen-Blicks C. Sugar fermentation in probiotic bacteria. An in vitro study. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2008;23:482–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2008.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haukioja A., Söderling E., Tenovuo J. Acid production from sugars and sugar alcohols by probiotic Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria in vitro. Caries Res. 2008;42:449–453. doi: 10.1159/000163020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaazou M.H., Abu El-Yazeed M., Galal M., Abd El rahman M., Mehanna N.S. A study of the effect of probiotic bacteria on level of Streptococcus mutans in rats. J Appl Sci Res. 2007;3(12):1835–1841. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prioult G., Fliss I., Pecquet S. Effect of probiotic bacteria on induction and maintenance of oral tolerance to betaglobulin in gnotobiotic mice. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:787–792. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.5.787-792.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayona González A., López Cámara V., Gómez Castellanos A. Prevention of caries with lactobacillus (final results of a clinical trial on dental caries with killed lactobacillus [streptococcus and lactobacillus] given orally) Pract Odontol. 1990;11(7):37–39. 42–43, 45–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Näse L., Hatakka K., Savilahti E. Effect of long-term consumption of a probiotic bacterium, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, in milk on dental caries and caries risk in children. Caries Res. 2001;35:412–420. doi: 10.1159/000047484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teughels W., Essche M.V., Sliepen I. Quirynen: probiotics and oral healthcare. Periodontology. 2000;48:111–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2008.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gedalia I., Dakuar A., Shapira L., Lewinstein I., Goultschin J., Rahamim E. Enamel softening with Coca-Cola and rehardening with milk or saliva. Am J Dent. 1991;4:120–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kashket S., Yaskell T. Effectiveness of calcium lactate added to food in reducing intraoral demineralization of enamel. Caries Res. 1997;31:429–433. doi: 10.1159/000262434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schupbach P., Neeser J.R., Golliard M., Rouvet M., Guggenheim B. Incorporation of caseinoglycomacropeptide and caseinophosphopeptide into the salivary pellicle inhibits adherence of mutans streptococci. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1779–1788. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750101101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahola A.J., Yli-Knuuttila H., Suomalainen T. Short-term consumption of probiotic-containing cheese and its effect on dental caries risk factors. Arch Oral Biol. 2002;47:799–804. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(02)00112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montalto M., Vastola M., Marigo L. Probiotic treatment increases salivary counts of Lactobacilli: a double-blind, randomized, controlled study. Digestion. 2004;69:53–56. doi: 10.1159/000076559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Çaglar E., Cildir S.K., Ergeneli S., Sandalli N., Twetman S. Salivary mutans streptococci and Lactobacilli levels after ingestion of the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 by straws or tablets. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64:314–318. doi: 10.1080/00016350600801709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikawa H., Makihira S., Fukushima H. Lactobacillus reuteri in bovine milk fermented decreases the oral carriage of mutans streptococci. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cagler E., kavaloglou S.C., Kuscu, Sandalli N., Holgerson P.L., Twetman S. Effect of chewing gums containing xylitol or probiotics bacteria on salivary mutans streptococci and Lactobacilli. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11(4):425–429. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Çaglar E., Kusku O.O., Cildir S.K., Kuvvetli S.S., Sandalli N. A probiotic lozenge administered medical device and its effect on salivary mutans streptococci and Lactobacilli. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caglar E., Kuscu O.O., Selvi Kuvvetli S., Kavaloglu Cildir S., Sandalli N., Twetman S. Short-term effect of ice-cream containing Bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12 on the number of salivary mutans streptococci and Lactobacilli. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008;66:154–158. doi: 10.1080/00016350802089467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petti S., Tarsitani G., Simonetti D'Arga A. A randomized clinical trial of the effect of yoghurt on the human salivary microflora. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:705–712. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(01)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caglar E., Sandalli N., Twetman S., Kavaloglu S., Ergeneli S., Selvi S. Effect of yogurt with Bifidobacterium DN-173 010 on salivary mutans streptococci and Lactobacilli in young adults. Acta Odontol Scand. 2005;63:317–320. doi: 10.1080/00016350510020070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yli-Knuuttila H., Snäll J., Kari K., Meurman J.H. Colonization of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the oral cavity. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:129–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirjavainen P., Gibson G.R. Healthy gut microflora and allergy: factors influencing development of the microbiota. Ann Med. 1999;31:288–292. doi: 10.3109/07853899908995892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brück W.M., Redgrave M., Tuohy K.M. Effects of bovine alpha-lactalbumin and casein glycomacropeptide-enriched infant formulae on faecal microbiota in healthy term infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(5):673–679. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000232019.79025.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Penders J., Thijs C., Vink C. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):511–521. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshioka H., Iseki K., Fujita K. Development and differences of intestinal flora in the neonatal period in breast-fed and bottlefed infants. Pediatrics. 1983;72(3):317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez P.F., Doré J., Leclerc M. Bacterial imprinting of the neonatal immune system: lessons from maternal cells? Pediatrics. 2007;119(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Könönen E., Kanervo A., Takala A., Asikainen S., Jousimies-Somer H. Establishment of oral anaerobes during the first year of life. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1634–1639. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780100801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Twetman S., Stecksén-Blicks C. Probiotics and oral health effects in children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy V., Rao A.P., Mohan G., Kumar R.R. Probiotic lactobacilli and oral health. Ann Essence Dent. 2011;3(2):100–103. [Google Scholar]