Abstract

Context:

Differential methylation of CpG regions is the best-defined mechanism of epigenetic regulation of gene expression.

Objective:

Our objective was to determine whether any changes in methylation are associated with aldosteronomas.

Methods:

We performed integrated genome-wide methylation and gene expression profiling in aldosteronomas (n = 25) as compared with normal adrenal cortical tissue (n = 10) and nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors (n = 13). To determine the effect of demethylation on gene expression of CYP11B2, the H295R cell line was used.

Results:

The methylome of aldosteronomas, normal adrenal cortex, and nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors was distinct, with hypomethylation of aldosteronomas. Integrated analysis of gene expression and methylation status showed that 53 of 60 genes were hypermethylated and downregulated, or hypomethylated and upregulated, in aldosteronomas. Of these, 3 genes that regulate steroidogenic signals and synthesis in adrenocortical cells were differentially methylated: AVPR1α and PRKCA were downregulated and hypermethylated, and CYP11B2 was upregulated and hypomethylated. Demethylation treatment resulted in upregulation of these genes, with direct hypomethylation of CpG sites associated with the genes. The CpG island in the promoter region of CYP11B2 was hypomethylated in aldosteronomas but not in blood DNA from the same patients (P = .0004).

Conclusions:

Altered methylation in aldosteronomas is associated with dysregulated expression of genes involved in steroid biosynthesis. Aldosteronomas are hypomethylated, and CYP11B2 is overexpressed and hypomethylated in these tumors.

Primary aldosteronism (Conn's syndrome) is caused by hypersecretion of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex. This condition is associated with significant morbidity and mortality if untreated and is the most common and curable cause of hypertension. Hypersecretion of aldosterone in primary aldosteronism is typically caused by an adrenocortical adenoma, bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, or unilateral adrenal hyperplasia (1, 2).

The principal regulators of aldosterone biosynthesis are 1) the renin-angiotensin system, 2) extracellular potassium concentration, and 3) ACTH. Angiotensin II or potassium leads to depolarization of the cell membrane and opening of voltage-dependent calcium channels, resulting in increased intracellular calcium concentrations. Angiotensin II can also signal through the angiotensin type I receptor, leading to stimulation of inositol trisphosphate-dependent calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum. This results in upregulation of CYP11B2 transcription (3). CYP11B2 encodes aldosterone synthase, the last enzyme that regulates aldosterone synthesis, and is upregulated in adrenal glands with cortical hyperplasia and adenoma, causing primary aldosteronism (4). Recently, KCNJ5 mutations have been identified in 12.5% to 65.2% of adrenal tumors causing primary aldosteronism (5–8). Moreover, mutations in KCNJ5 are associated with elevated CYP11B2 expression and higher aldosterone serum levels in some studies (8–10). More recently, somatic mutations in the P-type ATPase gene family, ATP1A1 and ATP2B3, and in CACNA1D have been identified in up to 6.8% of aldosteronomas (11–13). However, in the remaining cases of adrenal tumors causing primary aldosteronism, the genomic or genetic alterations resulting in primary aldosteronism remain unknown.

Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that are not due to changes in DNA sequence. The best-defined epigenetic change is DNA methylation of cytosines by DNA methyltransferase enzymes. Cytosines associated with guanines are called CpG dinucleotides. DNA sequences rich in CpG regions are called CpG islands and are defined as regions of greater than 500 base pairs that have GC content greater than 55% (14). Up to 60% of CpG islands are in the 5′ regulatory (promoter) regions of genes (15–17). Thus, DNA methylation status regulates gene expression and affects a number of different cellular processes, including apoptosis, cell cycle, DNA damage repair, growth factor response, and signal transduction, all of which may contribute to a variety of human disorders in target organs, as epigenetically driven events (18).

In this study, we performed an integrated analysis of genome-wide methylation and gene expression data in adrenal tumors causing primary aldosteronism compared with normal adrenal cortex and nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors. We found a distinct methylation profile in primary aldosteronism. Moreover, the altered methylation patterns were in the key genes that regulate aldosterone biosynthesis (CYP11B2, AVPR1a, and PRKCA). We performed in vitro studies to confirm the epigenetic regulation of these genes and verify that the methylation status of these genes is directly altered with a demethylating agent. More importantly, we demonstrated that CpG hypomethylation of CYP11B2 is specific to adrenal tumors compared with germline DNA from the same patients with primary aldosteronism.

Materials and Methods

Tissue and blood samples

Adrenocortical tissue and blood samples were collected according to an institutional review board-approved clinical protocol after written informed consent was obtained (NCI-09-C-0242, NCT01005654, and NCI-11-C-0149, NCT01348698). Forty-eight adrenal tissue samples (25 adrenal samples [22 adrenocortical adenomas and 3 adrenocortical hyperplasias] from patients with primary aldosteronism, 13 from nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors, and 10 from normal adrenal cortex) were obtained at surgical resection and immediately snap-frozen and stored at −80°C. Normal adrenal glands were obtained at the time of nephrectomy for organ donation and immediately snap-frozen and stored at −80°C. Patient blood samples were collected, after fasting, on the morning of the adrenalectomy for primary aldosteronism and nonfunctioning adrenal tumors. The clinical, laboratory, histologic, and genetic features of the study cohort are summarized in Table 1. All patients with primary aldosteronism had an aldosterone to renin ratio of >20, and confirmatory testing with a sodium chloride loading test, a captopril test, and or a posture test. Adrenal vein sampling was performed in all patients with primary aldosteronism for lateralization. All patients had lateralization based on a ratio at least 4 times greater than on the contralateral side and the peripheral samples. All patients with primary aldosteronism, with adrenal tissue samples used in this study, had an improvement in their hypertension (reduced blood pressure medication requirement or completely discontinued) within at least 6 months of follow-up.

Table 1.

Clinical, Laboratory, Histologic, and Genetic Characteristics of Study Cohort

| Normal Adrenal Cortex | Nonfunctioning Cortical Adenomasa | Primary Aldosteronism | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 10 | 13 | 25 |

| Age, y [mean (range)] | 40.6 (25–68) | 51.5 (24–77) | 49.4 (20–72) |

| Sex, , n (%) female | 7 (70) | 8 (62) | 14 (56) |

| Aldosterone level (reference range, ≤21 ng/dL) (mean ± SD) | NA | 14 ± 11 | 90.4 ± 148 |

| Renin level (reference range, 0.6–3 ng/mL) (mean ± SD) | NA | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 0.6 ± 0.6 |

| Aldosterone to renin ratio | NA | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 26.0 ± 4.9 |

| Potassium (reference range 3.3–5.1 mmol/L) (mean ± SD) | NA | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 0.8 |

| Adrenal gland histology, n | |||

| Normal | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Cortical hyperplasia | 1 | 4 | |

| Cortical adenoma | 12 | 21 | |

| Adrenal tumor size, cm (mean ± SD) | NA | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| KCNJ5 mutationb | |||

| No | 10 | 13 | 20 |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 5 |

Three cases had cortical adenoma with hyperplasia.

Type of KCNJ5 mutation: all in exon 2 (3 G151R and 2 L168R mutations).

Methylation profiling of tissue samples

Tissue was sectioned for DNA isolation and total DNA was extracted using DNA STAT-60 according to the manufacturer's instruction (Tel-Test Inc) or DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (QIAGEN). One microgram of DNA was bisulfite-converted using the EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit (Zymo Research Corporation) according to the manufacturer's protocol with a modified thermocycling procedure as suggested by Illumina (16 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds and 50°C for 60 minutes). The bisulfite-converted DNA (600 ng) was assayed on Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips using the Illumina Infinium HD Methylation Assay Kit (Illumina, Inc) (12). These chips assess the methylation status at >485 000 individual CpG sites encompassing 99% of RefSeq genes and 96% of CpG islands (18). Each DNA sample first underwent an overnight isothermal whole-genome amplification step. Amplified DNA was fragmented, precipitated, and resuspended. Samples were hybridized to BeadChips overnight at 48°C in an Illumina Hybridization Oven. Using an automated protocol on the Tecan Evo robot (TecanGroup Ltd), hybridized arrays were processed through a single-base extension reaction on the probe sequence using dinitrophenol- or biotin-labeled nucleotides, with subsequent immunostaining. The BeadChips were then coated, dried, and imaged on an Illumina HiScanSQ (Illumina). Image data were extracted using the Genome Studio version 2010.3Methylation module. Quality control inclusion valuation depended on hybridization average detection P values < .05. The final report file generated from the Genome Studio was processed by using Bioconductor packages methylumi and lumi as well as Partek GS. After data normalization, the M values were used for the statistical testing (ANOVA), and Benjamini and Hochberg-adjusted P value < .05 for multiple comparisons and an absolute β-value difference greater than 0.2 were applied for the final significant target list.

mRNA microarray of tissue samples

The same adrenal tissue used for methylation analysis was serially sectioned for RNA isolation and for hematoxylin and eosin staining to confirm diagnosis and tissue content. Total RNA was extracted from homogenized frozen tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and was purified using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). One microgram of total RNA was used for amplification and labeling with the MessageAmp aRNA kit (Ambion Inc). Fragmented and labeled cRNA (12 μg) was hybridized to a gene chip (Affymetrix Human Genome U133 plus 2.0 GeneChip) for 16 hours at 45°C. The gene chip arrays were stained and washed (Affymetrix Fluidics Station 400) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The probe intensities were measured using an argon laser confocal scanner (GeneArray scanner; Hewlitt-Packard).

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (800–1000 ng) was reverse transcribed using the Gene Amp RNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems). RT-PCR was used to measure mRNA expression levels relative to GAPDH mRNA expression. Normalized gene expression level = 2−(Ctgene-of-interest−CtGAPDH) × 100%, where Ct is the PCR cycle threshold. The PCR primers and probes for AVPR1a, PRKCA, CYP11B2, and GAPDH were obtained from Applied Biosystems. All PCRs were performed in a final volume of 10 μL with 2 μL of cDNA on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The PCR thermal cycler condition was 95°C for 15 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of 60°C for 1 minute. All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times.

KCNJ5 mutation analysis in tissue samples

KCNJ5 mutation analysis was performed in exons 1, 2, and 3; exon-intron boundaries; and flanking intronic regions as previously described (5). All PCR products were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm successful amplification of each exon. Direct sequencing of the purified fragments was performed using the Genetic Sequencer ABI3100 Applied Biosystems platform. Sequences were analyzed using Vector NTI 10 software (Invitrogen).

Pyrosequencing

Tissue and blood lymphocyte DNA was extracted using QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit. All samples had a DNA concentration of at least 10 ng/μL. Samples were sent to the Laboratory of Molecular Technology at the National Cancer Institute at Fredrick for percent methylation detection by pyrosequencing. Primers were designed for 115 base pairs in the CpG promoter region 11324259. DNA samples were PCR-amplified and pyrosequenced on QIAGEN Pyromark MD with positive and negative controls.

Cell culture

H295R cells (4 × 104) were seeded in a 24-well plate. After 24 hours, cells were treated with decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) at 1μM–10μM (Sigma) and vehicle for 24, 48, and 72 hours. The medium was replaced every 24 hours. Total RNA was extracted after 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment and analyzed for AVPR1a, PRKCA, and CYP11B2 mRNA expression. The experiments were repeated 3 times.

Statistical analysis

A paired t test was used to compare the difference in the methylation percentage via pyrosequencing between the DNA from aldosteronomas and the DNA from peripheral blood. A Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between CYP11B2 gene expression and methylation. A P value < .05 was considered significant. All calculations were performed using GraphPad Software.

Results

Methylation profile of normal adrenal cortex, nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors, and aldosteronomas

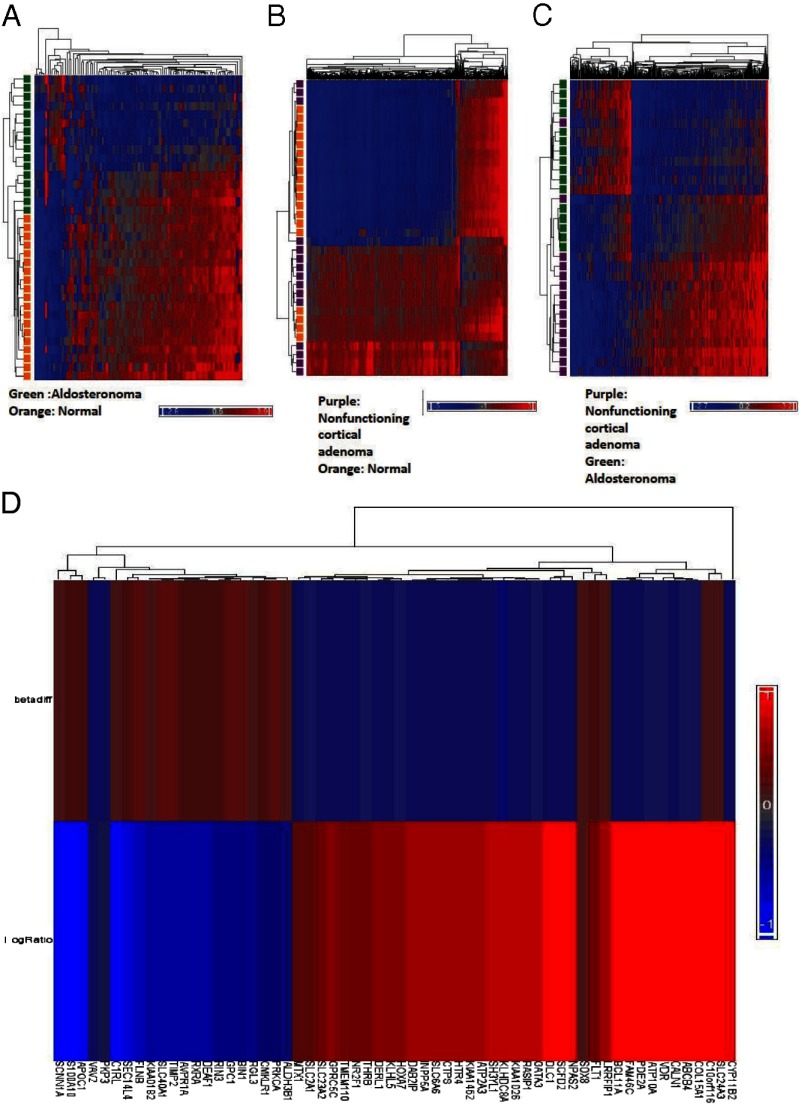

A genome-wide methylation comparison of normal adrenal cortex, nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors, and aldosteronomas showed distinct methylation patterns (Figure 1, A–C). There was complete separation between normal adrenal cortex and aldosteronomas and nearly complete separation between nonfunctioning tumors and normal adrenal cortex or aldosteronomas. The number of differentially methylated CpG sites was 97 for normal adrenal cortex vs aldosteronomas, 1590 for normal adrenal cortex vs nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors, and 523 for aldosteronomas vs nonfunctioning tumors, using an adjusted P value of < .05 with a β difference of at least .2. Moreover, aldosteronomas were hypomethylated compared with normal adrenal cortex and nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors. There was no significant difference in the methylation pattern of aldosteronomas with and without KCNJ5 mutations. When comparing adrenocortical adenoma and adrenocortical hyperplasia samples from patients with primary aldosteronism, we also observed no significant difference in the number of differentially methylated CpG sites or in the clustering of these samples (Figure 1 A–C).

Figure 1.

Cluster analysis of adrenal tissue sample methylome. A, Comparison of aldosteronoma and normal adrenal cortex methylome. B, Comparison of nonfunctioning cortical adenoma and aldosteronomas. C, Comparison of aldosteronoma and nonfunctioning cortical adenoma. Differential CpG methylation sites with adjusted P value < .05, with a β difference of at least .2. D, Heatmap of differentially methylated and expressed genes in aldosteronomas compared with nonfunctioning cortical adenomas. The notation betadiff represents methylation and exp_logRatio represents gene expression. The blue areas (0 to −1) illustrate downregulation or hypomethylation, whereas red (0 to +1) illustrates upregulation or hypermethylation.

We next performed integrated analysis of genome-wide methylation and gene expression data in the same tissue samples. This analysis showed 60 genes that were differentially methylated and differentially expressed in aldosteronomas. In 53 of the 60 genes, we observed the expected relationship between genes being downregulated and hypermethylated or upregulated and hypomethylated (Figure 1D).

Differentially expressed and methylated genes in aldosteronomas

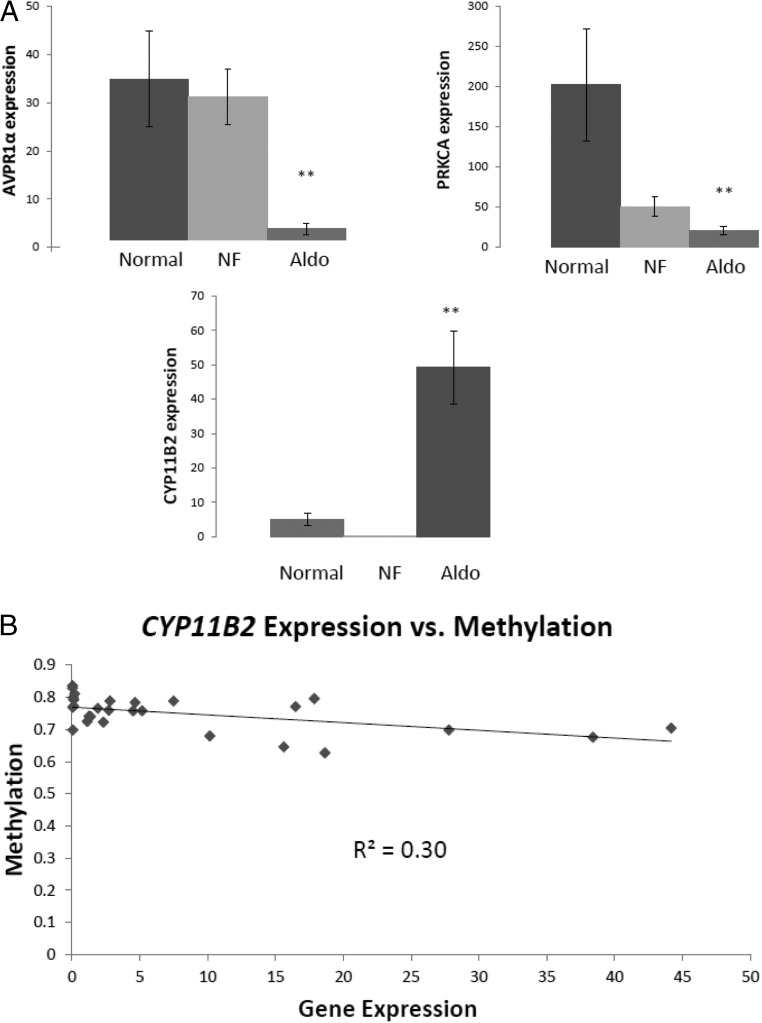

Analysis of the differentially methylated and expressed genes identified 3 genes known to be key regulators of steroidogenic signals and synthesis in adrenocortical cells (AVPR1α, PRKCA, and CYP11B2) (14, 15, 20). We validated the differential expression of these genes in normal adrenal cortex, nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors, and aldosteronomas by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 2A). AVPR1α and PRKCA mRNA expression was significantly lower in aldosteronomas, as compared with normal adrenal cortex and nonfunctioning tumors (9-fold lower than the expression in normal for both genes, and 8-fold and 2-fold lower, respectively, than the expression in nonfunctioning tumors). CYP11B2 mRNA expression in aldosteronomas was significantly higher than in normal adrenal cortex and nonfunctioning tumor samples (9-fold and 216-fold higher, respectively).

Figure 2.

Validation and correlation of differentially expressed and methylated genes. A, Validation of differentially expressed and methylated genes by quantitative RT-PCR in normal adrenal cortex, nonfunctioning cortical adenomas (NF), and aldosteronomas (Aldo). **, Significant difference (P < .05) between aldosteronomas and both nonfunctioning and normal adrenocortical tissues. Gene expression on the y-axis is 2−ΔCt × 100%. The x-axis represents the tissue sample category. Normal means normal adrenal cortex. B, Correlation of CYP11B2 expression and methylation in aldosteronomas, nonfunctioning cortical adenomas, and normal adrenocortical tissues. A Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between gene expression and methylation (P < .005).

Given the known action of these 3 genes in steroid biosynthesis, the expression pattern for AVPR1α and PRKCA was the opposite of promoting aldosterone synthesis, suggesting a negative feedback regulation that may be due to the hypermethylation of these 2 genes. On the other hand, CYP11B2 was upregulated and hypomethylated, suggesting that dysregulated methylation preferentially upregulates CYP11B2 with commensurate inhibition of other key genes involved in steroid biosynthesis. To further confirm the inverse relationship of CYP11B2 expression and methylation, we compared the methylation and expression status of this gene in individual tissue samples and found a significant correlation (P < .005) (Figure 2B).

Because CYP11B2 has been previously shown to be overexpressed in aldosteronomas and this expression may be higher in tumors with KCNJ5 mutations, we analyzed CYP11B2 expression to determine whether there was a difference in expression level by mutation status, but found no significant difference (9). We also found no difference in serum aldosterone levels based on KCNJ5 mutation status.

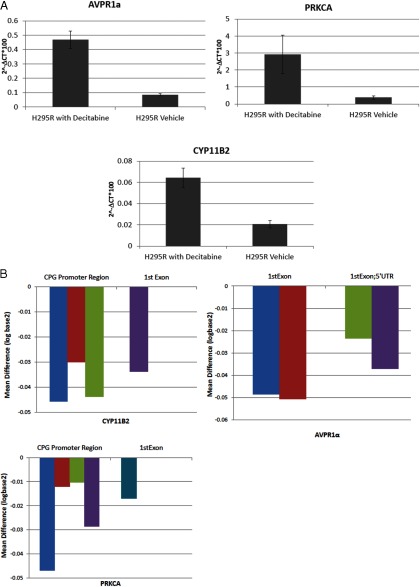

Decitabine treatment upregulates AVPR1α, PRKCA, and CYP11B2 expression

To determine whether the 3 genes that are involved in steroid biosynthesis and were differentially methylated and expressed are dependent on CpG methylation status to regulate gene expression, we treated the adrenocortical carcinoma cell lines NCI-H295R with a demethylating agent decitabine. We found increased expression of AVPR1α, PRKCA, and CYP11B2 with decitabine treatment (Figure 3A). This finding provides indirect evidence of the possible epigenetic regulation of these genes. Thus, we also determined whether decitabine directly alters the CpG methylation status of these genes in their CpG promoter sites and found that decitabine treatment significantly lowered CpG methylation in all 3 genes (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of decitabine on gene expression and CpG methylation in H295R cells. A, Gene expression changes with decitabine treatment; gene expression on the y-axis is 2−ΔCt × 100%. The x-axis represents the tissue sample category. Error bars represent SD. Data for 48 hours after decitabine treatment are normalized to GAPDH mRNA expression. B, CpG gene methylation status difference with decitabine treatment. Decitabine (10μM) compared with vehicle control. The y-axis is log2 of CpG methylation difference normalized to vehicle control. Each histogram on the x-axis represents an individual CpG methylation site.

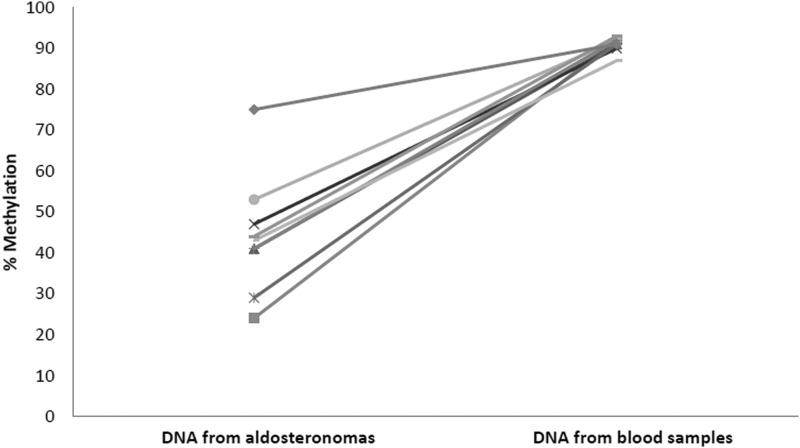

Differential methylation of CYP11B2 is specific to aldosteronomas

The hypomethylation and upregulation of CYP11B2 and the hypermethylation and downregulation of AVPR1α and PRKCA establish a novel model for the epigenetic regulation of aldosterone oversecretion in aldosteronomas. To determine whether CYP11B2 hypomethylation is a specific event to aldosteronomas in patients with primary aldosteronism, we compared the methylation status of CYP11B2 CpG islands in paired DNA samples from aldosteronomas and blood from the same patients. In all cases, CpG hypomethylation was found in aldosteronomas but not in peripheral blood DNA (P = .0004; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Paired analysis of CYP11B2 methylation in DNA samples from aldosteronomas and blood lymphocytes from the same patient (n = 9) showing percent methylation of CpG island in CYP11B2 promoter region.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the methylome of adrenocortical tumors causing primary aldosteronism. This analysis resulted in several novel findings that shed light on the molecular mechanism of primary aldosteronism. First, we found hypomethylation of aldosteronomas as compared with normal adrenal cortex and nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors. Second, we showed, based on integrated analysis of genome-wide methylation and gene expression data in the same tissue samples, that key genes involved in steroid biosynthesis are differentially methylated and expressed. These findings provide the first evidence of a mechanism by which CYP11B2 is upregulated in aldosteronoma through epigenetic regulation of this gene. Third, we found that the hypomethylation of CYP11B2 is specific to aldosteronomas.

AVPR1α and PRKCA were underexpressed and hypermethylated in aldosteronomas. AVPR1α is 1 of 3 major receptor types for arginine vasopressin, which are G protein-coupled receptors that stimulate the phosphatidylinositol-calcium second messenger system to regulate aldosterone in the zona glomerulosa and glucocorticoid in the zona fasciculate of the adrenal cortex (16, 17). PRKCA belongs to the protein kinase C protein family, which is involved in diverse cellular signaling pathways. In bovine adrenal zona glomerulosa cells, PRKCA has been shown to mediate the effect of G protein-coupled receptors, receptor tyrosine kinase, and sphingosine-1-phosphate on aldosterone secretion (18, 21). Thus, our results showing that AVPR1α and PRKCA are underexpressed in aldosteronomas suggest these genes do not contribute to aldosterone oversecretion in primary aldosteronism. The reduced expression of AVPR1α and PRKCA in aldosteronomas may be a result of a negative feedback mechanism caused by aldosterone hypersecretion and or the gene's methylation status.

Several investigators have reported the overexpression of CYP11B2 in aldosteronomas. Recently, Monticone and colleagues (9) also observed that CYP11B2 expression is higher in aldosteronomas with KCNJ5 mutations. To our knowledge, our results are the first to demonstrate methylome dysregulation in aldosteronomas and that this dysregulation is associated with dysregulated expression of genes involved in aldosterone biosynthesis. Demethylation treatment of the adrenocortical carcinoma cell line H295R, which expresses these genes, also indirectly supports the finding that AVPR1α, PRKCA, and CYP11B2 expression are regulated by an epigenetic mechanism.

Our comparison of the CYP11B2 DNA methylation status of adrenocortical tumors and blood lymphocytes confirmed that hypomethylation of this gene is specific to aldosteronomas. Although CYP11B2 is not expressed in blood lymphocytes, this comparison was performed because epigenetic changes could be mediated through a multitude of environmental and dietary factors, thus making it important to demonstrate the methylation change observed in the tumor (hypomethylation of CYP11B2) was not nonspecific.

The discovery of mutations in the KCNJ5, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, and CACNA1D genes have led to significant advances in our understanding of the genetic alterations associated with aldosteronomas. Collectively, these mutations may be present in approximately two-thirds of aldosteronomas and regulate Na+, K+, and Ca2+ transport to increase aldosterone synthesis and secretion (5–8, 12, 13). KCNJ5 mutations have been associated with higher serum aldosterone levels and CYP11B2 expression in aldosteronomas in some, but not all, studies (5, 7, 8, 23). However, a significant number of aldosteronomas do not harbor these mutations, and it is unclear how CYP11B2 is overexpressed in aldosteronomas, which has been uniformly observed in most studies. In the case of KCNJ5 mutations, the most common genetic alteration in aldosteronomas, we found no differences in tissue methylation, CYP11B2 expression in tissue, or serum aldosterone levels. We did not genotype the tumors studied for the other mutations (ATP1A1, ATP2B3, and CACNA1D) recently discovered, which may be associated with altered CpG methylation and or CYP11B2 overexpression but these genetic alterations are infrequent events in aldosteronomas. Our findings related to the epigenetic regulation of CYP11B2 reveal a novel mechanism by which CYP11B2 overexpression may occur in aldosteronomas.

There are some limitations to this study. The comparison in the genome-wide methylation analysis of normal adrenal cortex was not in the specific adrenocortical zones zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis, which secrete different hormones. Microdissection of the individual zones of the normal adrenal cortex, specifically the zona glomerulosa, which expresses CYP11B2 and secretes aldosterone, would be needed to make any definitive conclusions with respect to the comparison of aldosteronomas with normal adrenal cortex (24, 25). It is possible the methylation difference observed could be due to tissue-specific gene expression in the different adrenal cortex zones. Thus, our results regarding the hypomethylation and overexpression of CYP11B2 in primary aldosteronism adrenocortical tissue samples is compared with nonfunctioning adrenocortical tumors and including all 3 zones of the normal adrenal cortex.

In summary, our study shows that there are epigenetic changes in aldosteronomas that are associated with dysregulated expression of genes involved in steroid biosynthesis. Aldosteronomas are globally hypomethylated, and CYP11B2 is overexpressed and hypomethylated in these tumors. Furthermore, genes that regulate steroid biosynthesis are upregulated in vitro in cells treated with the demethylation agent decitabine, and this upregulation is associated with hypomethylation of CpG islands in their promoter region. Most importantly, the relative hypomethylation and overexpression of CYP11B2 appears to be specific to aldosteronomas, suggesting that drugs that promote DNA methylation may have a role in the treatment of patients with primary aldosteronism (19, 22).

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the intramural research program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1. Chao CT, Wu VC, Kuo CC, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary aldosteronism: an updated review. Ann Med. 2013;45:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zennaro MC, Jeunemaitre X, Boulkroun S. Integrating genetics and genomics in primary aldosteronism. Hypertension. 2012;60:580–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bird IM, Hanley NA, Word RA, et al. Human NCI-H295 adrenocortical carcinoma cells: a model for angiotensin-II-responsive aldosterone secretion. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1555–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bassett MH, Mayhew B, Rehman K, et al. Expression profiles for steroidogenic enzymes in adrenocortical disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5446–5455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xekouki P, Hatch MM, Lin L, et al. KCNJ5 mutations in the National Institutes of Health cohort of patients with primary hyperaldosteronism: an infrequent genetic cause of Conn's syndrome. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:255–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scholl UI, Nelson-Williams C, Yue P, et al. Hypertension with or without adrenal hyperplasia due to different inherited mutations in the potassium channel KCNJ5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2533–2538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taguchi R, Yamada M, Nakajima Y, et al. Expression and mutations of KCNJ5 mRNA in Japanese patients with aldosterone-producing adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1311–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331:768–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monticone S, Hattangady NG, Nishimoto K, et al. Effect of KCNJ5 mutations on gene expression in aldosterone-producing adenomas and adrenocortical cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1567–E1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boulkroun S, Beuschlein F, Rossi GP, et al. Prevalence, clinical, and molecular correlates of KCNJ5 mutations in primary aldosteronism. Hypertension. 2012;59:592–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beuschlein F, Boulkroun S, Osswald A, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 lead to aldosterone-producing adenomas and secondary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45:440–444, 444e441–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Azizan EA, Poulsen H, Tuluc P, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and CACNA1D underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1055–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scholl UI, Goh G, Stölting G, et al. Somatic and germline CACNA1D calcium channel mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1050–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shibata H, Ando T, Suzuki T, et al. COUP-TFI expression in human adrenocortical adenomas: possible role in steroidogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:4520–4523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perraudin V, Delarue C, Lefebvre H, Do Rego JL, Vaudry H, Kuhn JM. Evidence for a role of vasopressin in the control of aldosterone secretion in primary aldosteronism: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1566–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grazzini E, Boccara G, Joubert D, et al. Vasopressin regulates adrenal functions by acting through different vasopressin receptor subtypes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;449:325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guillon G, Trueba M, Joubert D, et al. Vasopressin stimulates steroid secretion in human adrenal glands: comparison with angiotensin-II effect. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1285–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brizuela L, Rabano M, Pena A, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate: a novel stimulator of aldosterone secretion. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1238–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pascale RM, Simile MM, De Miglio MR, Feo F. Chemoprevention of hepatocarcinogenesis: S-adenosyl-l-methionine. Alcohol. 2002;27:193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. LeHoux JG, Dupuis G, Lefebvre A. Regulation of CYP11B2 gene expression by protein kinase C. Endocr Res. 2000;26:1027–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shah BH, Baukal AJ, Shah FB, Catt KJ. Mechanisms of extracellularly regulated kinases 1/2 activation in adrenal glomerulosa cells by lysophosphatidic acid and epidermal growth factor. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2535–2548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Campbell PM, Bovenzi V, Szyf M. Methylated DNA-binding protein 2 antisense inhibitors suppress tumourigenesis of human cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:499–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Osswald A, Fischer E, Degenhart C, et al. Lack of influence of somatic mutations on steroid gradients during adrenal vein sampling in aldosterone-producing adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169:657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Enberg U, Volpe C, Höög A, et al. Postoperative differentiation between unilateral adrenal adenoma and bilateral adrenal hyperplasia in primary aldosteronism by mRNA expression of the gene CYP11B2. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:73–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boulkroun S, Samson-Couterie B, Golib-Dzib JF, et al. Aldosterone-producing adenoma formation in the adrenal cortex involves expression of stem/progenitor cell markers. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4753–4763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]