Abstract

Background

This study examined the relations between treatment process variables and child anxiety outcomes.

Method

Independent raters watched/listened to taped therapy sessions of 151 anxiety-disordered (6 -14 yr-old; M = 10.71) children (43% boys) and assessed process variables (child alliance, therapist alliance, child involvement, therapist flexibility and therapist functionality) within a manual-based cognitive-behavioral treatment. Latent growth modelling examined three latent variables (intercept, slope, and quadratic) for each process variable. Child age, gender, family income and ethnicity were examined as potential antecedents. Outcome was analyzed using factorially derived clinician, mother, father, child and teacher scores from questionnaire and structured diagnostic interviews at pretreatment, posttreatment and 12-month follow-up.

Results

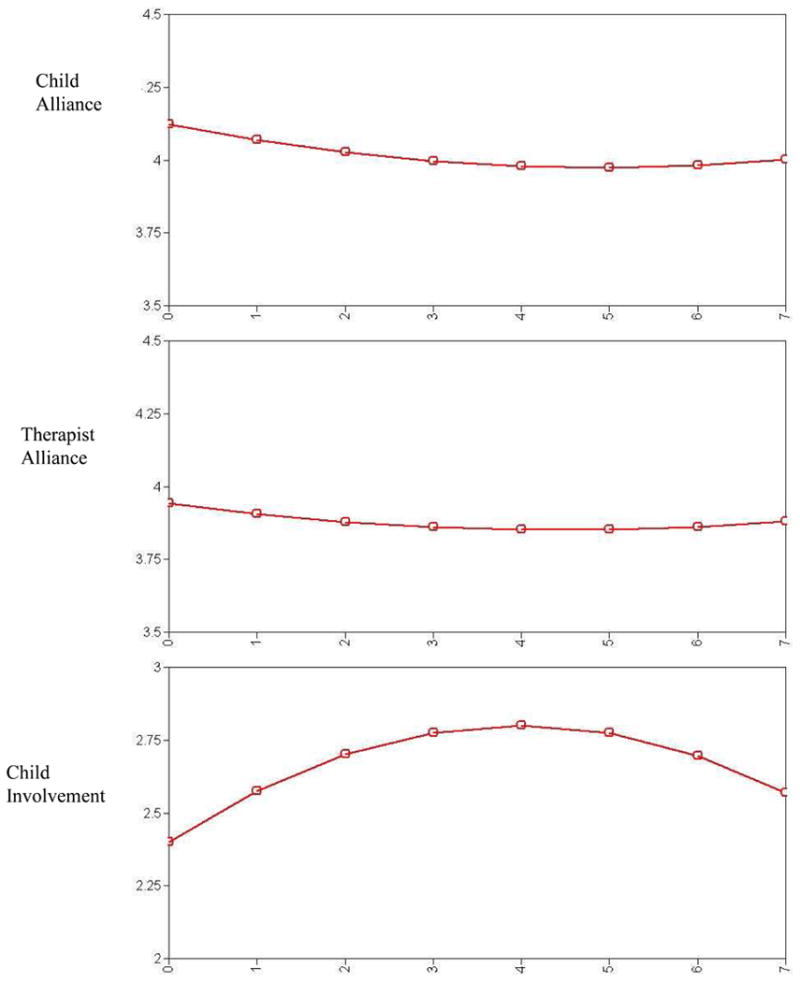

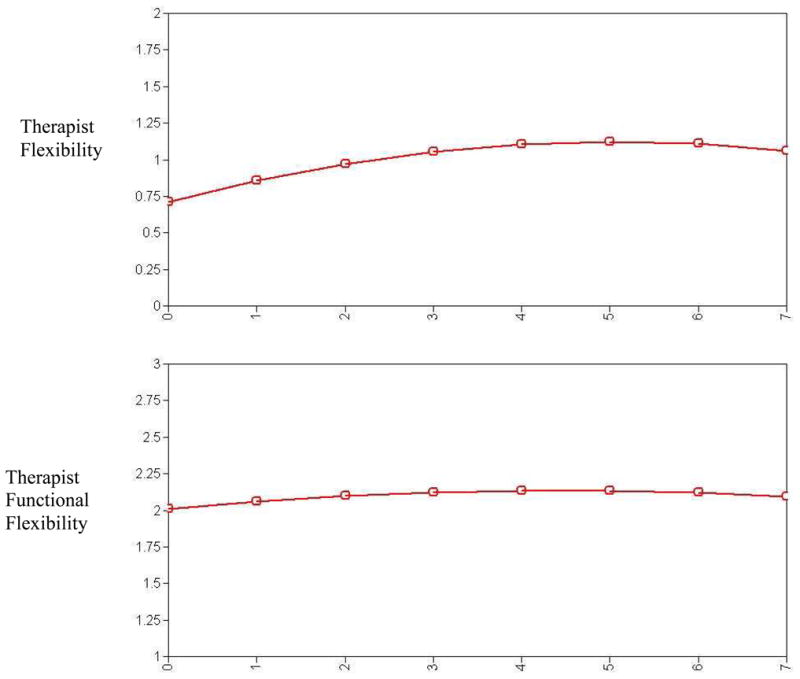

Latent growth models demonstrated a concave quadratic curve for child involvement and therapist flexibility over time. A predominantly linear, downward slope was observed for alliance, and functional flexibility remained consistent over time. Increased alliance, child involvement and therapist flexibility showed some albeit inconsistent, associations with positive treatment outcome.

Conclusion

Findings support the notion that maintaining the initial high level of alliance or involvement is important for clinical improvement. There is some support that progressively increasing alliance/involvement also positively impacts on treatment outcome. These findings were not consistent across outcome measurement points or reporters.

Keywords: Therapy process, alliance, child involvement, flexibility, child anxiety

Analysis of the process of change in interventions for anxiety in youth has been relatively neglected (Kendall & Ollendick, 2004; Kazdin & Nock, 2003; Shirk & Russell, 1998). In an early review of child therapy studies, Kazdin, Bass, Ayers, and Rodgers (1990) found that less than 3% of child therapy studies examined treatment processes, but recommended that such research could facilitate our understanding of the mechanisms of change and help to improve our empirically supported treatments. Others have argued that process research could smooth the path for dissemination of evidence-based treatments (Kendall & Beidas, 2007).

Recent years have evidenced a significant increase in attention to child and therapist process variables in youth-based psychotherapy. Karver, Handelsman, Fields, and Bickman (2006) conducted a meta- analysis on child treatment studies and identified moderate- to – large relationships between treatment outcome and process variables that focused on therapist alliance, parent and youth participation willingness, and client and parent actual participation (weighted effect size =.26). Similarly, Fjermestad, Haugland, Heiervang, and Ost (2009) found evidence of significant associations between relationship variables and outcomes, but concluded that the literature was still preliminary due to inconsistent measurement of relationship variables.

Research examining the effect of client involvement in RCT with manual-based therapy has been limited. Chu and Kendall (2004) found that child involvement in manual-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was associated with the absence of the principal anxiety diagnosis after treatment. Involvement has also been associated with other processes such as alliance (Tryon & Kane, 1995). Together, these findings suggest that involvement is an important process variable in child therapy.

Therapeutic alliance has a well-developed research history in the adult literature (Horvath & Bedi, 2002; Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000) and a developing literature for youth treatment. It describes a number of constructs including the therapeutic or working relationship; therapeutic bond and treatment involvement. In child and family community clinics, therapeutic relationship problems were identified as the major factor that distinguished therapy dropouts from completers, (Garcia & Weisz, 2002) and self-report assessment of therapist-child and therapist-parent alliance have been associated with treatment retention, satisfaction, and improved symptoms (Hawley & Weisz, 2005). Shirk and Karver (2003) conducted a meta-analytic review of child and adolescent treatments, and found a small, but significant, overall effect size between alliance and treatment outcome. The results suggested that therapist-ratings of alliance were stronger predictors of treatment outcome than child ratings. Research, however, examining alliance-outcome relationships specifically in the treatment for anxious children has been mixed. Although some studies have identified significant relations between treatment outcome and the therapeutic relationship (McLeod and Weisz (2005) Chiu, McLeod, Har, and Wood (2009), other studies have found limited support Liber et al. (2010).

Current clinical recommendations suggest adhering to manual – based treatments with a flexible and individualised manner (Kendall, Chu, Gifford, Hayes, & Nauta, 1998). This “flexibility within fidelity” principle helps ensure that treatment is individually responsive yet retains its core principles and strategies (Kendall et al., 1998). Using independent observer ratings Chu and Kendall (2009) found that therapist flexibility was positively and significantly related to mid-treatment child involvement and child involvement predicted diagnostic improvement. Prior research however did not assess the degree to which therapist flexibility was in response to the child (or just part of the therapist's approach). Preferred therapist flexibility (here defined as functional flexibility) would be that which is matched to the child's needs.

The present study examined process variables in CBT for anxiety disorders in children. The process variables, coded from three previous RCTs, were child involvement, therapeutic alliance, therapist flexibility, and functional flexibility, as rated by independent coders viewing/listening to taped sessions. Latent growth modelling was used to accomplish three objectives. First, mean growth trajectories were estimated for the two child process variables and three therapist variables. There is limited research to inform hypotheses about overall mean trajectories for these variables, but preliminary evidence suggests stable courses or slight decreases over time for alliance and child involvement (Chiu et al., 2009; Chu & Kendall, 2004; Liber et al., 2010). In contrast, Kendall et al. (2009) recently identified a different pattern in which participant-reports of alliance increased gradually over the first half of treatment before levelling off after mid-treatment.

Our second aim was to identify relations among the process variables. Again, limited research is available, but meta-analyses (Fjermestad et al., 2009; Karver et al., 2006) suggest small to medium relations among relationship factors (e.g., involvement, child alliance, therapist alliance) and preliminary evidence suggests possible associations between child involvement and therapist flexibility (Chu & Kendall, 2009). Third, it was hypothesized that child and therapist variables would predict post-treatment and one-year follow-up outcomes across all reports.

Method

Participants

Children (N = 151 ages 6-14; 71 boys) and their parents completed independent structured diagnostic interviews conducted by separate diagnosticians. Child diagnoses were obtained from the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV-C/P or ADIS-III-R-C/P; Silverman, 1987; Silverman & Albano, 1996) conducted at the Child and Adolescent Anxiety Disorders Clinic (CAADC), Temple University. Children participated in an RCT (n = 44 from Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008; n = 58 from Kendall et al., 1997; n= 20 from Flannery-Schroeder & Kendall 2000; n = 29, Kendall, 1994), if they met DSM criteria for a primary diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD; n = 77), Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD, n = 36), Social Phobia (SP; n = 37) and Panic Disorder (PD; n = 1) based on ADIS-C/P composite diagnosis. Eighty-eight percent of children had a comorbid anxiety disorder, 15.7% met criteria for ADHD, 6.4% for mood disorder, and 8.7% had an externalizing disorder. Children (M age = 10.71, SD = 1.68) were European American (130; 86.7%), African American (6; 6%), Asian (2; 1.3%), Hispanic (4; 2.7%), other (5; 3.3%) and missing (4; 2.6%).

Therapy sessions (1 through 16) were recorded, and the audio/videotapes were examined and coded. Tapes were excluded for if missing or inaudible. All available tapes were rated. The average number of rated tapes per participant was 11.07 (SD = 2.93; Range = 3 – 16). The average number of taped sessions unavailable for rating was 30.8% per participant. All participants had tapes available from early (sessions 1 through 4), mid (sessions 5 through 8), and late (sessions 9-16) therapy sessions. A greater number of tapes were unavailable for sessions 9 through 16 as these sessions focused on exposure tasks that were sometimes completed outside the therapy room. The percentage of unavailable tapes from sessions 9-16 was 40.4%.

Outcome Measures

The Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for Children and Parents (ADIS-IV-C/P or ADIS-III-R-C/P; Silverman, 1987; Silverman & Albano, 1996) is a child and parent semi-structured interview to enable diagnosis according to DSM categories. Impairment ratings are given separately by the child and parents, and each are considered in deriving composite diagnoses. Both the ADIS-III – C/P and the ADIS – IV – C/P have favourable psychometric properties (Lyneham, Abbott, & Rapee, 2007)Silverman & Nelles, 1988).

Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1978) is a 37-item self-report measure that assesses trait anxiety in 6-19 year-olds producing four subscales: anxiety, physiological symptoms, worry and oversensitivity, and social concern-concentration. The RCMAS has high internal consistency, moderate retest reliability (r = .68), and reasonable construct validity (Reynolds & Paget, 1982).

Coping Questionnaire-Child (CQ-C; Kendall, 1994) assesses the child's perceived ability to manage anxiety-provoking situations. The CQ is situationally-based and individualized: 3 areas of difficulty are chosen based on interview data, and each child rates his/her ability to cope with each on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all able to help myself to 7 = completely able to help myself feel comfortable). The CQ-C has strong retest reliability (Kendall & Marrs-Garcia, 1999).

Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) is a widely used 118-item parent-report measure of behavioural, emotional, social, academic problems in children measured on a 3 – point scale (0 =not true, 1 =somewhat or sometimes true, 2 =very/often true). The measure generates T scores on Internalizing and Externalizing Problems as well as the Withdrawn and Anxiety/Depression subscales. Validity, internal consistency, and retest reliability have been documented (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Teacher Report Form (TRF;Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986) provides data on the child's classroom functioning, similar to the CBCL. The child's primary teachers completed this measure. Internalizing, Externalizing, Withdrawn, and Anxiety/Depression subscales were used in the current study. The TRF has high retest reliability, moderate inter-teacher agreement, and discriminates between referred and nonreferred children.

Process Measures

Child Involvement Rating Scale-Revised (CIRS-R adapted from Chu & Kendall, 2004) is a psychometrically sound twelve-item scale measuring child involvement in therapy as rated by trained observers. The CIRS-R contains eight positive involvement items (e.g., Does the child initiate discussion or introduce new topics?) and four items of negative involvement (e.g., Is the child inhibited or avoidant in participation?). Two positive involvement items were added to the original CIRS measure to capture children's disclosure of anxious emotion and cognition (e.g., Does the child disclose anxious, fearful or worried feelings?). Items are rated on a 6-point scale from 0 (Not at all) to 5 (A great deal) and the two negative involvement items are reverse-scored. A mean CIRS score was computed for each session. The CIRS has shown moderately strong internal consistency (coefficient α = .73; Chu & Kendall, 2004). The CIRS has demonstrated strong inter-rater reliability (ICC = .76), and moderate retest reliability (ICC = .59; Chu & Kendall, 2004).

Child Psychotherapy Process Scales (CPPS: Estrada & Russell, 1999) assesses both positive and negative aspects of child and therapist behaviours and attitudes through 13 child and 15 therapist items, rated by independent observers, measured on a 5-point scale (1= not at all, 5= a great deal). The measure includes 3 global ratings (1= very poor, 5 = excellent). A manual was developed for the purposes of this study and coders only utilized the child and therapist therapeutic alliance scales from the CPPS. The child therapeutic alliance factor includes 8 items measuring cooperation, negative reactions, interest, and compliance, openness to feedback, trust, synchrony, and global impression of the relationship. The therapist therapeutic alliance factor includes 5 items measuring warmth and friendliness of the therapist, empathy, synchrony, and global impression of the relationship. Mean child and therapist alliance scores were computed for each session. The CPPS has moderate/good inter-rater reliability (Estrada & Russell, 1999), good internal consistency, and strong discriminant validity (Russell, Bryant, & Estrada, 1996).

Coping Cat Protocol Adherence Checklist-Modified (CCPAC-M; Southam-Gerow, Jensen-Doss, Gelbwasser, Chu, & Weisz, 2001) is a treatment adherence checklist that includes a rating of the therapist's flexibility and a new rating of the functional appropriateness of the flexibility. The flexibility and the degree of functional appropriateness with which a therapeutic task is implemented is rated on a 6-point scale (0 = not at all flexible/functionally appropriate; 5 = extremely). Mean flexibility and functional flexibility scores were calculated for each session. Test restest reliability of flexibility is moderate (Chu & Kendall, 2009)

Procedure

Coder Training

Coders (n = 12) were provided readings on childhood anxiety, its treatment, coding manuals for the process measures, then tested to evaluate their knowledge. Coders used manuals to code each of the process variables, watching and coding training sessions. Coders were required to reach a reliability of .80 on each of the factor scores (intra-class correlation for interval data; Kappa for agreement data). Coders not reaching the criteria continued watching training tapes and coding separate tapes until the criteria were met. Coders were blind to treatment outcome.

Results

Reliability Assessments

Inter-rater reliability was conducted at post training; midway and at the end of coding. Tapes were given to coders at intervals throughout. Coders discussed their ratings, and discrepancies were discussed and resolved. At the end of coding, overall ICC for all scale and subscale scores was assessed. Child variables: Therapeutic Alliance = .81; Child Work = .83; Child Readiness = .83; CIRS = .90. Therapist Variables: Therapeutic Alliance = .80; Technical Work = .75; Technical Lapse = .69; PACM-adherence = .93; Flexibility = .82; Functional Flexibility = .83. Variables with < .80 reliability were not examined further.

To avoid potential overlap between process variables, particularly between therapeutic alliance and child involvement, a principal components factor analysis (with varimax rotation) was conducted on the CPPS and CIRS items across a selection of the 16 sessions. Results found that CIRS negative involvement items tending to load more strongly with the alliance items. Thus, a decision was made to remove the negative involvement items resulting in an 8-item positive child involvement scale. Internal reliabilities across the 16 sessions were as follows: Child Alliance (alpha = .89-.95); Therapist Alliance (alpha = .74-.90); Child Involvement (alpha = .82-92).i

Data reduction techniques were employed to reduce the number of variables. First, mean session scores of process variables were averaged to form 8 time-points of data across treatment (e.g. sessions 1-2, sessions 3-4,) reducing the percentage of missing data to 16.6%. PCA, (using the maximum likelihood estimation and Direct Oblimin rotation) was also used to identify five latent factors underlying parent, child, and teacher report outcome measures. Factors were consistent with report source (see Table 1). Missing data was minimal for the PCA as it was conducted on treatment outcome measures. The father-report factor did have missing data from 31.2%, but the remaining data provided a sufficient sample to variable ratio (30:1) to conduct PCA. The resulting factor also demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = .88). Using unit weighting, we averaged standardized values of each factor's measures to compute a factor score for each participant. To obtain posttreatment and follow-up factor scores on metrics comparable to those of the pretreatment factors, we standardized each of the post and follow-up factor's measures using pretreatment means and standard deviations.

Table 1. Factor loadings for latent factors underlying parent, child and teacher-report outcome measures.

| Factor | Loading |

|---|---|

| Child Report | |

| RCMAS-Anxiety | .97 |

| RCMAS-Physiological | .88 |

| RCMAS-Worry | .88 |

| RCMAS-Social Anxiety | .81 |

| Mother Report | |

| CBCL-Withdrawn | .75 |

| CBCL-Anxiety/Depression | .88 |

| CBCL-Internalizing | .92 |

| CBCL-Externalizing | .67 |

| Coping Factor | |

| CQ-Mother | .41 |

| CQ-Child | .43 |

| Teacher Report | |

| TRF-Withdrawn | .83 |

| TRF-Anxiety/Depression | .88 |

| TRF-Internalizing | .96 |

| TRF-Externalizing | .47 |

| Father Report | |

| CBCL-Withdrawn | .72 |

| CBCL-Anxiety/Depression | .93 |

| CBCL-Internalizing | .93 |

| CBCL-Externalizing | .80 |

Note: RCMAS = Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale. CBCL: Child Behaviour Checklist. TRF: Teacher report Form. CQ: Coping Questionnaire.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for the process variables across eight time points. Significant changes across the three assessment periods were determined using an overall test of within-subjects effects (See Table 3 p's < .001; alpha set at 0.05).

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of the child and therapist process variables across 8 time-points.

| Session 1-2 | Session 3-4 | Session 5-6 | Session 7-8 | Session 9-10 | Session 11-12 | Session 13-14 | Session 15-16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 146 | n = 137 | n = 139 | n = 132 | n = 129 | n = 115 | n = 114 | n = 96 | |

| Child Alliance | 4.12 (.47) | 4.06 (.60) | 4.04 (.58) | 3.93 (.68) | 4.04 (.58) | 4.00 (.63) | 3.93 (.63) | 3.99 (.70) |

| Audio | 4.20 (.41) | 4.13 (.58) | 4.06 (.57) | 3.99 (.63) | 4.07 (.58) | 4.02 (.61) | 4.01 (.59) | 3.97 (.61) |

| Video | 3.94 (.55)* | 3.95 (.56) | 3.94 (.53) | 3.83 (.68) | 3.92 (.48) | 3.91 (.49) | 3.83 (.56) | 4.10 (.58) |

| Therapist Alliance | 3.94 (.48) | 3.93 (.57) | 3.87 (.59) | 3.78 (.64) | 3.89 (.57) | 3.91 (.59) | 3.81 (.58) | 3.88 (.67) |

| Audio | 3.98 (.42) | 3.99 (.52) | 3.89 (.55) | 3.79 (.60) | 3.88 (.52) | 3.91 (.54) | 3.83 (.50) | 3.84 (.52) |

| Video | 3.83 (.57) | 3.83 (.59) | 3.81 (.61) | 3.77 (.63) | 3.82 (.57) | 3.85 (.55) | 3.79 (.62) | 4.02 (.63) |

| Child Involvement | 2.35 (.76) | 2.65 (.87) | 2.76 (.80) | 2.70 (.84) | 2.77 (.78) | 2.72 (.92) | 2.75 (.85) | 2.64 (.93) |

| Audio | 2.33 (.67) | 2.68 (.77) | 2.73 (.75) | 2.70 (.77) | 2.72 (.74) | 2.63 (.80) | 2.64 (.72) | 2.38 (.80) |

| Video | 2.41 (.92) | 2.62 (.99) | 2.81 (.88) | 2.73 (.88) | 2.94 (.73) | 2.94 (.92)* | 2.99 (.87)* | 3.04 (.85)* |

| Therapist Flexibility | .67 (.65) | .94 (.69) | .94 (.70) | 1.09 (.86) | .97 (.82) | 1.22 (.88) | 1.13 (86) | 1.01 (.75) |

| Audio | .59 (.60) | .85 (.67) | .85 (.65) | .92 (.77) | .81 (.78) | 1.05 (.73) | .89 (.70) | 1.03 (.83) |

| Video | .88 (.69)* | 1.09 (.66)* | 1.22 (.68)* | 1.5 (.86)* | 1.32 (.79)* | 1.54 (.86)* | 1.61 (.93)* | 1.16 (.74) |

| Therapist Functional Flexibility | 2.09 (.87) | 2.17 (.87) | 2.13 (.94) | 2.15 (.85) | 2.18 (.93) | 2.27 (.91) | 2.24 (.92) | 2.11 (1.03) |

| Audio | 1.76 (.76) | 1.92 (.81) | 1.86 (.88) | 1.93 (.76) | 1.92 (.84) | 1.89 (.78) | 1.92 (.82) | |

| Video | 2.48 (.82)* | 2.60 (.78)* | 2.58 (.81)* | 2.60 (.79)* | 2.65 (.72)* | 2.62 (.77)* | 2.72 (.78)* | 1.79 (.86) 2.80 (.76)* |

Note:

indicates a significant difference between audio and video (p < .05).

Table 3. Means and standard deviations (at pretreatment, posttreatment, and 1-year follow-up) of child treatment outcome variables.

| Pre | Post | Follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | n | M(SD) | n | F valuesa |

| CSR | -.01 (.99) | 14 | -1.91 | 13 | -2.31 | 11 | F(2, 224) = 146.28*** |

| 7 | (1.45) | 6 | (1.37) | 6 | |||

| Child report | -.04 (.77) | 15 | -.58 (.73) | 13 | -.73 (.74) | 11 | F(2, 218) = 76.07*** |

| 0 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| Mother | -.03 (.80) | 14 | -.71 (.89) | 12 | -.86 (.91) | 10 | F(2, 198) = 68.00*** |

| report | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Teacher | -.03 (.85) | 14 | -.45 (.77) | 11 | -.50 (.66) | 84 | F(2, 136) = 22.57*** |

| report | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Coping | .00 (.79) | 14 | 1.27 (.93) | 13 | 1.60 (.86) | 11 | F(2, 216) = 162.41*** |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Father | .00 (.89) | 10 | -.53 (.90) | 86 | -.63 (.71) | 72 | F(2, 118) = 29.31*** |

| 7 |

Note: CSR: clinical severity rating of the primary diagnosis. Child: RCMAS subscales. Mother and Father: CBCL subscales withdrawn A/D, internalizing and externalizing. Teacher: TRF subscales withdrawn, A/D, internalizing, externalizing. Coping: Coping Questionnaire-Mother, Coping Questionnaire-Child. Significance tests using these variables are to document that, for the present sample, there was positive gain associated with the treatment. However, because the data come from RCTs that have been reported, these analyses are NOT to be taken as separate evidence for the efficacy of treatment.

F values represent the tests of within-subjects effects.

p < .001.

We compared the process variables form sessions that were coded by audio and video and found some differences (see Table 2). Coders were more likely to provide higher ratings of alliance in sessions 1 and 2, lower child involvement during exposure sessions (sessions 11-16), and lower flexibility during all except the last two sessions and functional flexibility across all sessions when coding data from audio compared to video (p < .05). There were no differences in child involvement, therapist alliance or later child alliance between audio and video presentation.

Latent growth models: Process Variables over Time

Latent growth models (LGM; Duncan, Duncan & Stryker, 2006) were estimated for each process variable. The aim was to model the trajectories of the process variables and to assess the influence of antecedent variables on the trajectories and the influence of the trajectories on consequent variables. The validity of the results of the LGM analyses presented here rests on the assumption that the data on the process variables (approximately 17% for each variable) are missing completely at random (MCAR) or at least missing at random (MAR) (see, for example, Schafer & Graham, 2002). If one of these assumptions -- that missingness is independent of all the variables in the dataset (MCAR), or random conditional on the values of the measures collected (MAR) -- is met, analyses utilising full information maximum-likelihood, as used here, provide for valid inference (Schafer & Graham, 2002, Enders, 2001). In this study, there were a number of factors leading to missingness: technical problems (e.g., therapist forgetting to record, or failure of the recording equipment); also, “in vivo” exposure sessions outside the therapy room were less likely to be recorded. Withdrawal from the study accounted for very little of the missing data, as there were only three such instances. As might be expected, given the main reasons for missing data, there were no systematic correlations between values of the antecedent variables and the missingness of the process variables, or between values of the process variables and the missingness of the variables at subsequent time points. The presence of such correlations may be reassuring if the validity of the analysis rests on the assumption of MAR, but their absence is consistent with the stronger assumption of MCAR. Such an assumption is consistent with the known reasons for missing data, which were such that missingness was unlikely to be related to the values which would have been obtained had they not been missing. Support for the validity of this assumption is provided by Little's test of MCAR. The test was applied to all of the data used in the analysis (process data along with antecedent and consequent variables) and to the process data alone. In neither case was the null hypothesis of MCAR contradicted: χ2 (2647) = 2632.3, p = .577, and χ2 (3007) = 2977.5, p = .645 respectively.

Initial models consisted of three latent variables, representing the intercept, linear slope (referred to as ‘linear’) and quadratic parameters. Mplus 7 was used to test the models. The linear and quadratic coefficients were set at zero for the first measure of the process variable. Consequently, the value for the intercept latent variable represented the first measure of the process variable for each subject (i.e., Sessions 1 and 2). The intercepts for the observed variables (the eight process measures in this case) were set to zero so that the means of the latent variables could be estimated; the variance of the residuals of the observed variables was freely estimated.

Adequate or better fits were obtained for child and therapist alliance, child involvement and therapist flexibility (Table 5), in some cases following modifications to the basic model: for teacher alliance, the error for Sessions 5 and 6 was allowed to correlate with the error for Sessions 7 and 8, and for therapist flexibility measures at Sessions 13 and 14 and Sessions 15 and 16 the path coefficients for the linear and quadratic latent variables were estimated rather than being fixed at the standard values as described above. The latter modifications allowed the model to accommodate the rather irregular trajectory for therapist flexibility over time. The trajectory for therapist functional flexibility, however, was such that it could not be accommodated by any of the LGMs fitted, which included latent variables with cubic and quintic latent varibles and freely-estimated rather than fixed paths. No LGM results are presented for this measure.

Table 5. Means, variances and fit indices for latent growth models for each process variable.

| Means | Variances | Fit indices | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Intercept | Slope | Quadratic | Intercept | Slope | Quadratic | χ2(df = 27) | CFI | TLI | RM SEA |

| Child Alliance | 4.12*** | -.06** | 0.05 | 0.19*** | .03** | .00** | 39.56 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.06 |

| Therapist Alliance | 3.94*** | -0.04** | 0.00 | 0.21*** | .02** | 0.00* | 52.21 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.08 |

| Child Involvement | 2.40*** | 0.18*** | -0.02*** | 0.46*** | 0.04* | 0.00** | 65.07 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.10 |

| Therapist Flexibility | 0.70*** | 0.16*** | -.014 | 0.31*** | .12*** | 0.01*** | 51.02 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.09 |

| Therapist Functional Flexibility | 2.01*** | 0.06 | -0.01 | 0.40*** | -0.02 | 0.00 | 10.52 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 0.00 |

Note:

p < 0.001

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Some measures demonstrated change over time. There was a significant negative linear slope for Child alliance, indicating a small overall average decline in child alliance over the course of therapy. Therapist alliance demonstrated a similar pattern, but the linear variable was only marginally significant.

The linear and quadratic variables were significant for Child Involvement, indicating an inverted u-shape, characterized by an increase in child involvement early in therapy, a peak during early exposures (sessions 9-10), and a final decline in involvement towards the end of therapy. Therapist flexibility showed a similar pattern with a significant negative effect for the quadratic latent variable and overall positive slope peaking in the first four exposure sessions (Sessions 9-12).

Table 4 reports the correlations among the latent variables (intercept, linear and quadratic) and illustrate direction and magnitude of relations among the four process variables.

Table 4. Correlations of Intercept, Slopes and Quadratric Latent Variables for the 5 Process Variables.

| (n = 151) | Therapist Alliance | Child Involvement | Therapist Flexibility | Therapist Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercepts | ||||

| Child Alliance | .82*** | .64*** | -.16 | -.05 |

| Therapist Alliance | 1 | .70*** | .14 | .17 |

| Child | 1 | .26** | .33*** | |

| Involvement Therapist Flexibility | 1 | .58*** | ||

| Slopes | ||||

| Child Alliance | .76*** | .58*** | -.01 | -.06 |

| Therapist Alliance | 1 | .57*** | -.03 | -.08 |

| Child Involvement | 1 | -.05 | -.11 | |

| Therapist Flexibility | 1 | .21 | ||

| Quadratics | ||||

| Child Alliance | .75*** | .51*** | -.02 | .08 |

| Therapist Alliance | 1 | .52*** | .01 | .04 |

| Child Involvement | 1 | -.02 | .10 | |

| Therapist Flexibility | 1 | .26 | ||

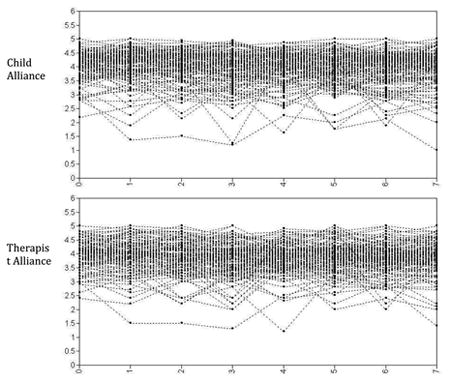

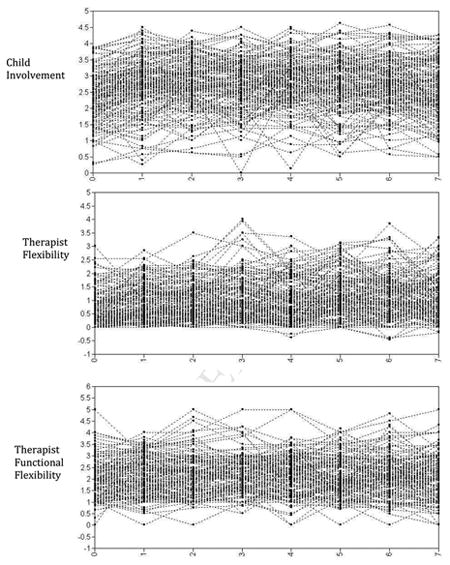

Individual trajectories of the observed process variables were also plotted across the 8 time-points, demonstrating significant variation across youth (see Appendix). Do we want to retain these plots? I would have thought that reporting the variance estimates of the parameters would be sufficient. Variance estimates for the intercept, linear and quadratic variables in the LGMs were significantly different from zero for all four process variables. These results indicate significant inter-individual variance that could be explained by between-youth predictors.

LGM: Predictors and Outcomes of Process

The power of the LGM procedure is that it provides a value for each subject, on each latent variable, which represents an aspect of the trajectory of the measured variables (therapeutic process for each case) over time. It is therefore possible to relate both antecedent and consequent variables to the latent variables (Duncan et al., 2006). Tests of possible effects of antecedent variables (child gender, age, child grade and family income) on the latent variables were carried out in Mplus. Tests of individual variables showed that Child gender was significantly related to the intercept term for Therapist Flexibility (b = .26, p < .05), indicating that therapists demonstrated significantly more flexibility with male clients in sessions 1 and 2. There were no other significant effects for individual variables.

In further analyses, an overall test was carried out for each process variable by comparing models in which all three latent variables were regressed on the four antecedent variables with models which included the antecedent variables but in which the paths from the antecedent variables were constrained to zero. Chi-squared difference tests failed to show any overall association between the antecedent variables and the latent variables for any of the process variables.

Tests of the consequent effects of the latent variables on outcome measures were conducted with a series of LGMs carried out with MPLUS. Each of the six outcome factors (CSR, Child-, Mother-, Father- and Teacher-report, and Coping) was individually regressed on the intercept, linear and quadratic latent variables, separately for pre-post and pre-FU. The post or FU outcome score for the relevant factor score was entered as the dependent variable, the pretreatment score for the outcome factor was entered as a covariate, and the intercept, linear and quadratic latent variables were entered as predictor variables. The covariances between the latent variables and the pre scores were freely estimated. Unstandardised regression weights are reported.

Limited significant results were found on the consequent effects of the latent variables on outcome factors (CSR, Child report, Mother report, Father report, Teacher report, and Coping). For child alliance, the intercept latent variable predicted changes from pre to posttreatment: mother reported symptoms (b = -.43, p = .027), teacher reported symptoms (b = -.48, p = .007), and Coping (b = .67, p = .002). The child alliance linear predicted changes in Coping from pre to post (b = 3.15, p = .024). The follow-up scores for teacher reported symptoms and Coping were predicted by the intercept for child alliance (b = -.50, p = .008 and b = .561, p = .020 respectively) and the former was predicted by child alliance linear (b = -2.34, p = .032).

For therapist alliance, the intercept latent variable predicted changes from pre to post treatment in mother reported symptoms (b = -.40, p = .015) teacher reported symptoms (b = -.34, p = .028) and Coping (b = .58, p = .002). Follow-up teacher reported symptoms were predicted by both linear (b = -3.80, p = .002) and quadratic (b = -29.0, p = .013) latent variables. The quadratic effect suggests that more positively accelerated increases in therapist alliance are associated with greater reductions in teacher reported symptoms.

For child involvement, the intercept latent variable predicted pre to post changes in Coping (b = .28, p = .026). The intercept latent variable predicted pre to follow-up change in Coping (b = .41, p = .002) and the linear latent variable predicted follow-up teacher reported symptoms (b = -2.17, p = .023). Tests of consequent effects on the latent variables for Therapist flexibility yielded only one significant effect, with the intercept predicting child reported symptoms at follow-up (b = -.28, p = .029).

Discussion

The current study used taped sessions from multiple RCT's of CBT for children with anxiety disorders. Results found that measures of child and therapist process variables demonstrated several between-process relations and associations with treatment outcome. The current study was the first to utilize observer-ratings of weekly sessions for multiple client and therapist factors and provides the most comprehensive description available in the literature of the shape of change for child and therapist alliance, child involvement, and therapist flexibility across the course of CBT for anxious youth.

Our first interest was establishing mean trajectories for process variables across the course of treatment. Child and therapist alliance ratings demonstrated a predominantly linear, downward slope for alliance over time. The magnitude of the decline was small in each instance (approximately .04 - .06 points for every two sessions) and is consistent with previous studies that have found either stable or slight alliance decreases from early to later sessions (Chiu et al., 2009; Liber et al., 2010). Therapists are able to sustain a high level of alliance with their child clients throughout therapy. Child involvement and therapist flexibility measures demonstrated a concave quadratic curve, indicating a single peak occurring roughly around mid-treatment (session 8 and 9). Like alliance results above, this pattern contrasted with the only other report of involvement over time (Chu & Kendall, 2004) which reported decreasing child involvement from early to mid-treatment sessions. Compared to child involvement, therapist flexibility peaked slightly later, between sessions 10-12, and demonstrated a less steep decline in later therapy.

The trajectory of therapist functional flexibility was unable to be fitted using LGM. Observation of the means indicates that this variable largely conformed to a straight model with relatively little change in scores during therapy. This is the first assessment of therapist flexibility over multiple sessions, making comparisons difficult. Ideally, this rating would start and remain high. The mean for this variable is just below the midpoint of the scale, indicating slightly lower functional flexibility than desired.

Our second aim was to identify relations among process variables. As expected, absolute values (intercepts) of early (sessions 1 and 2) child and therapist alliance were highly correlated with each other and with early child involvement. This indicates that average values of positive child process are highly related early in therapy, but not entirely overlapping. In addition, early therapist efforts to demonstrate warmth, empathy and synchrony are positively related to youth engagement in treatment activities and openness to the relationship. Child involvement also showed small significant relations with both flexibility measures early in therapy. This is consistent with previous studies where therapist flexibility was found to be positively related to child involvement under some circumstances (Chu & Kendall, 2009).

The slopes of child and therapist alliance were also highly and positively related and slope values for both child and therapist alliance were highly correlated with the slope value for child involvement. Similar findings were identified for quadratic values of client variables. As therapists demonstrate increased or decreased relationship-building qualities, child alliance and child involvement generally increase or decrease. In contrast, growth in therapist flexibility did not co-vary with growth in alliance or involvement.

Our final aim was to examine relations between client process variables and treatment outcomes. Our results provide initial, albeit inconsistent, evidence that some measures of client variables have significant impact on treatment outcomes. The majority of significant relations between process variables and treatment outcome occurred with the intercept latent variables, with only a few significant associations between outcome and linear or quadratic latent variables. That is, for the most part when process variables were significant predictors of outcome, it was the therapeutic process in sessions 1 and 2 that were important. For example, in predicting post treatment outcomes, higher child and therapist alliance scores consistently predicted higher coping scores and reduced mother and teacher reported symptoms. Some significant effects were observed for the linear variables and one significant effect for a quadratic latent variable. For example, changes in child alliance over time predicted changes in coping and teacher reported symptoms, such that increases in alliance were associated with greater coping at post treatment and reduced teacher report symptoms at follow-up. The only quadratic effect was found for therapist alliance suggesting that positively accelerated increases in therapist alliance are associated with greater reductions in teacher reported symptoms. Increases in child involvement over the course of therapy also predicted improvements in teacher reported symptoms.

These findings are consistent with meta-analytic reviews that identify significant relations between therapeutic relationship and treatment outcome (Shirk & Karver, 2003; Karver et al., 2008). However, the effects were not consistent across outcome measures or across measurement points. The current findings support the notion that maintaining the initial high level of alliance or involvement is related to positive clinical improvement. There is some, albeit weak, support that progressively increasing alliance/involvement also positively impacts on treatment outcome.

Only one direct association was found between therapist flexibility and treatment outcome, yet early levels of flexibility were associated with early levels of child involvement. This is largely consistent with previous research that has failed to identify direct relations between flexibility and treatment outcome but possible indirect relations through child involvement (Chu & Kendall, 2009; Kendall & Chu, 2000).

The large number of variables, and the lack of consistency between relations suggest that future research is needed to confirm the results. The use of two types of recording may also have led to biased results, as differences evident in the therapeutic process when coded from audio and video. Using video recordings, coders were more likely to rate lower child alliance in sessions 1 and 2, higher child involvement in later sessions and greater therapist flexibility and functionality. The presence of both auditory and visual information increases the information available to the coders and is likely to lead a more accurate depiction of the therapeutic process. It is possible that the use of audio recordings for the majority of our participants led to less accurate information about the therapeutic process. Last, further research is needed to investigate other potential mediational models that investigate the interaction of process variables and multiple pathways in predicting treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Estimated means for each Process variable over time using pooled multiply-imputed data.

Highlights.

herapists maintained a high level of alliance with their clients.

hild involvement and therapist flexibility peaked around mid treatment.

herapist flexibility was related to child involvement in the initial sessions.

mprovements in alliance and were associated with increases in child involvement.

nitial (and improved) alliance or involvement are related to positive outcome.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant MH60653 awarded to Philip C. Kendall, Jennifer L Hudson, Elizabeth Gosch and Brian Chu. Thank you to the many committed coders involved in this study.

Appendix

Individual trajectories (observed) for each Process variable across time.

Footnotes

Alpha coefficient not appropriate for Flexibility and Functionality due to the nature of the scale. Flexibility and functionality only rated when manual content was coded as present.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jennifer L. Hudson, Macquarie University

Philip C. Kendall, Temple University

Brian C. Chu, Rutgers University

Elizabeth Gosch, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Erin Martin, National Institute of Mental Health.

Alan Taylor, Macquarie University.

Ashleigh Knight, Macquarie University.

References

- Achenbach T. Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Edelbrock C. Manual for the TRF and the Child Behaviour Profile. Burlington VT: University of Vermont; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu AW, McLeod BD, Har K, Wood JJ. Child-therapist alliance and clinical outcomes in cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(6):751–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01996.x. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Kendall PC. Positive Association of Child Involvement and Treatment Outcome Within a Manual-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Children With Anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(5):821–829. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.821. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Kendall PC. Therapist responsiveness to child engagement: Flexibility within manual-based CBT for anxious youth. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(7):736–754. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20582. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Stryker LA. An introduction to lateng growth curve modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Second. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada A, Russell R. The development of the child psychotherapy process scale. Psychotherapy Research. 1999;9:154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fjermestad KW, Haugland BSM, Heiervang E, Ost LG. Relationship factors and outcome in child anxiety treatment studies. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;14(2):195–214. doi: 10.1177/1359104508100885. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359104508100885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery-Schroeder EC, Kendall PC. Group and individual cognitive-behavioral treatments for youth with anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24(3):251–278. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005500219286. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, Weisz JR. When youth mental health care stops: Therapeutic relationship problems and other reasons for ending youth outpatient treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):439–443. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, Weisz JR. Youth Versus Parent Working Alliance in Usual Clinical Care: Distinctive Associations With Retention, Satisfaction, and Treatment Outcome. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):117–128. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_11. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Bedi RP. Psychotherapy relationships that work: Therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. New York, NY: Oxford University Press US; 2002. The alliance; pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Handelsman JB, Fields S, Bickman L. Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: The evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Bass D, Ayers WA, Rodgers A. Empirical and clinical focus of child and adolescent psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58(6):729–740. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.729. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1994a;62:100–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994b;62(1):100–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Beidas RS. Smoothing the trail for dissemination of evidence-based practices for youth: Flexibility within fidelity. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38(1):13–20. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.1.13. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Chu B, Gifford A, Hayes C, Nauta M. Breathing life into a manual: Flexibility and creativity with manual-based treatments. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1998;5(2):198–278. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1077-7229%2898%2980004-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Comer JS, Marker CD, Creed TA, Puliafico AC, Hughes AA, Hudson J. In-session exposure tasks and therapeutic alliance across the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):517–525. doi: 10.1037/a0013686. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow M, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomized clincal trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(3):366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Marrs-Garcia A. Psychometric analyses of a therapy - sensitive measure: The Coping Questionnaire (QC) 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Liber JM, McLeod BD, Van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, van der Leeden AJ, Utens EM, Treffers PD. Examining the relation between the therapeutic alliance, treatment adherence, and outcome of cognitive behavioral therapy for children with anxiety disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41(2):172–186. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.003. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham H, Abbott M, Rapee RM. Inter-rate reliability of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Version. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:731–736. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180465a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis M. Relation of the therapeutic alliance withoutcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(3):438–450. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR. The Therapy Process Observational Coding System-Alliance Scale: Measure Characteristics and Prediction of Outcome in Usual Clinical Practice. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(2):323–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What i think and feel: A revised measure of children's manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6(2):271–280. doi: 10.1007/bf00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick JA. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83(404):1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Russell RL, Bryant FB, Estrada AU. Confirmatory P-Technique Analyses of Therapist Discourse: High-Versus Low-Quality Child Therapy Sessions. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(6):1366–1376. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Karver M. Prediction of Treatment Outcome From Relationship Variables in Child and Adolescent Therapy: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):452–464. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W. Childhood anxiety disorders: Diagnostic issues and future research. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychotherapy. 1987;4:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (DSM-IV) San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tryon GS, Kane AS. Client involvement, working alliance, and type of therapy termination. Psychotherapy Research. 1995;5(3):189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Jensen Doss A, Gelbwasser A, Chu BC, Weisz JR. Coping Cat Adherence Checklist – Flexibility Scale (CCPAC-F) 2001 Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.