Abstract

Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1), a potent keratinocyte growth inhibitor, has been shown to be overexpressed in keratinocytes in certain inflammatory skin diseases and has been thought to counteract the effects of other growth factors at the site of inflammation. Surprisingly, our transgenic mice expressing wild-type TGFβ1 in the epidermis using a keratin 5 promoter (K5.TGFβ1wt) developed inflammatory skin lesions, with gross appearance of psoriasis-like plaques, generalized scaly erythema, and Koebner's phenomenon. These lesions were characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation, massive infiltration of neutrophils, T lymphocytes, and macrophages to the epidermis and superficial dermis, subcorneal microabscesses, basement membrane degradation, and angiogenesis. K5.TGFβ1wt skin exhibited multiple molecular changes that typically occur in human Th1 inflammatory skin disorders, such as psoriasis. Further analyses revealed enhanced Smad signaling in transgenic epidermis and dermis. Our study suggests that certain pathological condition-induced TGFβ1 overexpression in the skin may synergize with or induce molecules required for the development of Th1 inflammatory skin disorders.

Keywords: angiogenesis, epidermis, Smads, Th1 inflammation

Introduction

Transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) is a multifunctional cytokine that functions via a heteromeric receptor complex of TGFβRI and TGFβRII (Miyazono et al, 2001). When TGFβ binds to a TGFβRI–TGFβRII complex, the classic TGFβRI, also known as activin receptor-like kinase-5 (ALK5), phosphorylates signaling mediators Smad2 and Smad3. Phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 form heteromeric complexes with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus to regulate TGFβ-responsive genes (Miyazono et al, 2001). Smad2/Smad3 activation mediates TGFβ1-induced growth inhibition in epithelial and endothelial cells (Goumans et al, 2002). Another type I TGFβR, ALK1, is preferentially expressed in endothelial cells. Activated ALK1 phosphorylates and activates Smad1 and Smad5, which positively regulate endothelial proliferation and migration (Goumans et al, 2002). TGFβ signaling is also negatively regulated by Smad6 and Smad7 (Miyazono et al, 2001).

TGFβ1 is secreted as a latent form. Active TGFβ1 is released when an N-terminal latency-associated peptide (LAP) is cleaved from the C-terminal mature (active) TGFβ1 (Lawrence, 1991). Two site-specific mutations in the LAP, Cys-223 → Ser and Cys-225 → Ser (TGFβ1S223/225), prevent the LAP from binding to the mature TGFβ1, resulting in a constitutively active TGFβ1 protein (Brunner et al, 1989). To study the functions of TGFβ1 in the skin in vivo, several transgenic mouse models have been made, which target overexpression of TGFβ1S223/225 to the epidermis. For instance, overexpression of TGFβ1S223/225 in the epidermis using a keratin 1 (K1) promoter severely inhibits keratinocyte growth (Sellheyer et al, 1993). In contrast, K10 or K6 promoter-driven TGFβ1S223/225 resulted in epidermal hyperproliferation, but no histological changes in transgenic skin (Cui et al, 1995; Fowlis et al, 1996). In an inducible TGFβ1S223/225 transgenic model using a mouse loricrin promoter, sustained TGFβ1S223/225 transgene induction exerts a growth-inhibitory effect on the epidermis and a paracrine effect on angiogenesis (Wang et al, 1999). Using a K14 promoter-based inducible transgenic model, Liu et al (2001) reported that chronic induction of TGFβ1S223/225 in basal keratinocytes and hair follicles only inhibits keratinocyte growth in neonates, whereas adult transgenic skin exhibited keratinocyte hyperproliferation, fibrosis, and inflammation. The contradictory data from the above models highlight the complex role of TGFβ1 in the skin, which may depend on its expression at different levels, locations, or developmental stages. As endogenous TGFβ1 is overexpressed under certain pathological conditions, it is of great interest to elucidate the effects of TGFβ1 on both the epidermis and the dermis under these conditions. To mimic such a condition, we decided to use a K5 promoter to target wild-type (latent) TGFβ1 (TGFβ1wt) (K5.TGFβ1wt). The K5 promoter targets transgene expression to the basal layer of the epidermis and hair follicles (He et al, 2002). As TGFβ1wt has a much longer plasma half-life than TGFβ1S223/225 (Wakefield et al, 1990), its half-life is expected to be longer in specific tissues. We reasoned that these two factors will facilitate the paracrine effects of TGFβ1 on the dermis. With TGFβ1wt transgene expression levels equivalent to the peak level of endogenous TGFβ1 in normal mouse skin during wound healing, K5.TGFβ1wt mice unexpectedly developed phenotypes and molecular alterations similar to those in Th1 inflammatory skin diseases in humans, such as psoriasis (Nickoloff and Wrone-Smith, 1999). As minor mechanical trauma is sufficient to induce endogenous TGFβ1 overexpression (Nickoloff and Naidu, 1994) and elicits lesions in patients with psoriasis (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999), our results suggest that TGFβ1 overexpression plays a pathological role in certain Th1 inflammatory skin diseases. The complex actions of TGFβ1 on inflammation, keratinocyte proliferation, angiogenesis, and basement membrane (BM) degradation identified in this model highlight the significance of the interplay between the autocrine and paracrine effects TGFβ1 in vivo.

Results

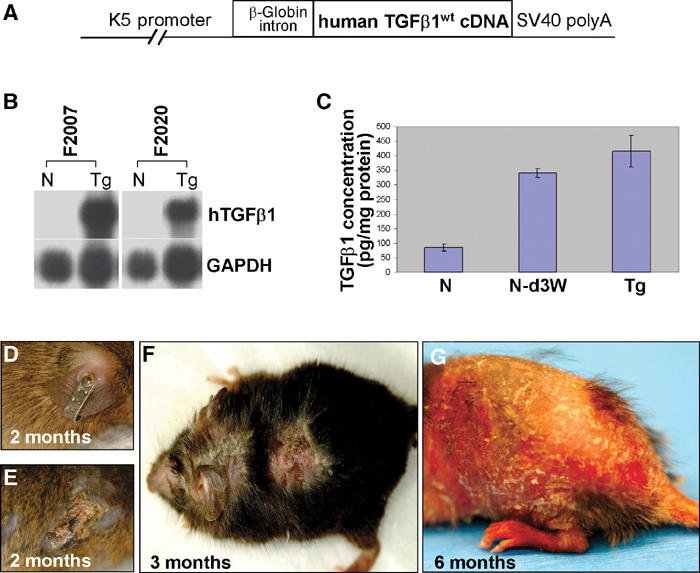

K5.TGFβ1wt mice developed a psoriasis-like skin disorder

To generate K5.TGFβ1wt transgenic mice, we inserted the wild-type human TGFβ1 cDNA into a K5 vector (Figure 1A). Two K5.TGFβ1wt transgenic lines, F2020 and F2007, were established, which expressed similar levels of the transgene (Figure 1B). To determine the levels of TGFβ1wt protein, ELISA was performed on protein extracts from individual transgenic and control skin. The total amount of TGFβ1 protein was 85.02±12.48 pg/mg protein in nontransgenic skin (n=5) and 416.67±53.96 pg/mg protein in transgenic skin (n=5, P<0.01, Figure 1C). The amount of TGFβ1 protein in transgenic skin was comparable with the peak level of endogenous TGFβ1 in control mouse skin after wounding, that is, on day 3 after a 6-mm full-thickness punch biopsy (341.20±14.49 pg/mg protein, n=3, P>0.05, Figure 1C), which subsequently returns to baseline levels (not shown).

Figure 1.

Generation of K5.TGFβ1wt mice and gross phenotypes. N: nontransgenic; Tg: transgenic. (A) The K5.TGFβ1wt transgene. (B) RPA indicating transgene (hTGFβ1) expression in transgenic skin from two founder lines, F2007 and F2002. (C) ELISA for TGFβ1 protein level in nontransgenic skin (N), day 3 wounded nontransgenic skin (N-d3W), and K5.TGFβ1wt transgenic skin. (D, E) Tagged ear of a 2-month-old control littermate (D) and a K5.TGFβ1wt mouse (E). (F) Typical inflammatory lesions on a 3-month-old K5.TGFβ1wt mouse. (G) Generalized scaly erythema in a 6-month-old transgenic mouse.

The transgenic founders were mated to an ICR or C57BL6 background. In both backgrounds, the founders and their offspring gave rise to identical phenotypes. K5.TGFβ1wt mice remained grossly normal until about 1 month post partum (p.p.), when they began to develop skin inflammation. Notably, normal littermates did not develop an inflammatory response upon ear tagging (Figure 1D), whereas every transgenic mouse developed a focal lesion on the tagged ear by 2 months (Figure 1E), reminiscent of Koebner's phenomenon in which a mechanical trauma induces or exacerbates psoriatic lesions (Christophers and Mrowietz, 1998). By 3 months of age, K5.TGFβ1wt skin developed focal erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance (Figure 1F). As skin inflammation progressed, the entire K5.TGFβ1wt skin became scaly and erythematous (Figure 1G), similar to psoriatic erytheroderma in humans (Christophers and Mrowietz, 1998).

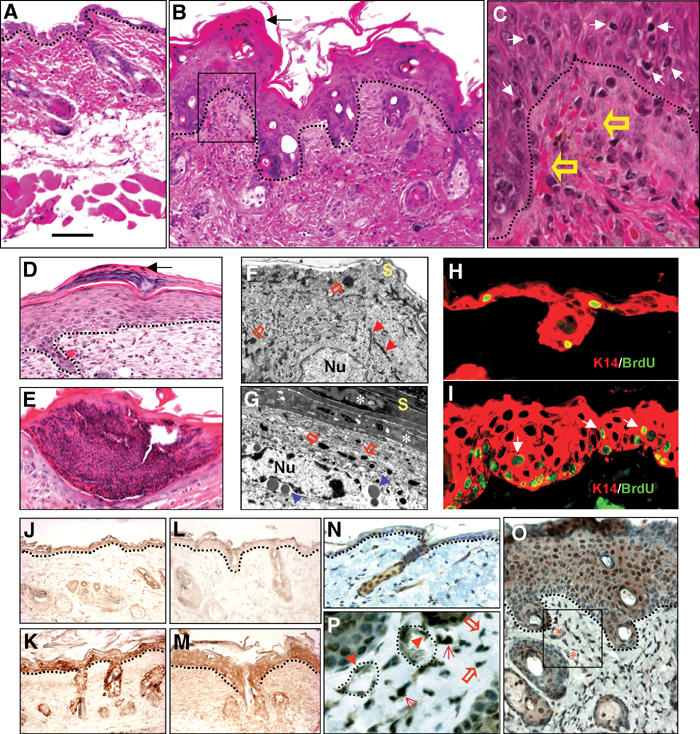

Prior to forming overt skin lesions, skin inflammation in transgenic mice began to be obvious at the microscopic level at day 17 p.p. when the hair follicles were maximally elongated such that more transgene-expressing keratinocytes are present in the skin. At this stage, transgenic skin exhibited infiltration of mixed inflammatory cells, angiogenesis, vasodilatation, and aberrant K6 expression in the epidermis (Supplementary data). Subsequently, inflammation became chronic and persistent in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. Compared with nontransgenic adult skin (Figure 2A), transgenic skin exhibited a thickened stratum corneum in which nuclei were retained (parakeratosis) or lost (hyperkeratosis), and a hyperplastic epidermis (acanthosis) with diminished granular layers (Figure 2B–D). Scattered mononuclear cells (Figure 2C) and subcorneal microabscesses containing mixed mononuclear cells and neutrophils (Figure 2E) were observed in K5.TGFβ1wt epidermis. Electron microscopy (EM) revealed a marked reduction of tonofilaments, the absence of fusion between keratohyalin granules and tonofilaments, and increased lipid vesicles in transgenic keratinocytes, especially in granular cells (Figure 2G), as compared with nontransgenic epidermis (Figure 2F). These alterations are common in human psoriasis (Jahn et al, 1988). The bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling index was 2.6±1.1 cells/mm epidermis in nontransgenic skin (Figure 2H), but was 6.6±1.6 cells/mm epidermis in transgenic skin (n=5, P<0.01), and BrdU-labeled cells were expanded in the suprabasal epidermis (Figure 2I). Finally, the transgenic dermis exhibited neovascularization, enlarged capillary cavities, and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Microscopic changes of 3-month-old transgenic skin. (A) Nontransgenic skin; (B–E) transgenic skin. Black arrows in (B) and (D) point to parakeratosis. Dotted lines in (A–D, J–O) denote the boundary between the epidermis and the dermis. The boxed area in (B) is enlarged in (C) to highlight clustered erythrocytes (open arrows) in dermal papillae as well as mononuclear cells in the epidermis (white arrows). Typical parakeratosis (D) and subcorneal microabscesses (E) in transgenic skin. (F, G) EM (× 11 500) reveals representative keratinocytes in the granular layer from control (F) and transgenic skin (G). Nu: nucleus; S: stratum corneum. Red arrows point out tonofilaments (F). Note the retained nuclei (asterisks) in the stratum corneum, keratohyalin granules (open arrows) without tonofilaments, and vesicles (blue arrows) in the granular layer of transgenic epidermis (G). (H, I) BrdU labeling (green) in control (H) and transgenic epidermis (I). Arrows in (I) point to suprabasal proliferative cells. Sections were counterstained with a K14 (red) antibody. (J–P) Immunohistochemistry of latent TGFβ1 (J, K), active TGFβ1 (L, M), and pSmad2 (N–P) (hematoxylin counterstained) in control (J, L, N) and transgenic (K, M, O, P) skin. Vessels (asterisks) from the boxed area of (O) are shown in (P). Cells with positive nuclear staining are pointed with arrowheads for endothelial cells, open arrows for fibroblasts, and arrows for inflammatory cells. The dotted line in (P) denotes the border of microvessels. The bar in panel (A) represents 100 μm for (A, B, D, E, J–M); 40 μm for (H, I, N, O), and 15 μm for (C,P).

The pathological alterations in transgenic epidermis and dermis suggested the autocrine and paracrine effects of TGFβ1wt. Different from previously reported TGFβ1 transgenic mice targeted by a K14 promoter, in which the latent TGFβ1 transgene is not activated in non-wounded skin (Yang et al, 2001), we observed increased immunostaining of both latent and active TGFβ1 in transgenic epidermis and dermis compared with nontransgenic skin (Figure 2J–M). This result suggests that the latent TGFβ1 can be secreted into and activated in transgenic epidermis and dermis. Accordingly, nuclear staining of phosphorylated Smad2 (pSmad2) was increased in transgenic epidermis and dermis compared with nontransgenic skin (Figure 2N–P). Cells positive for pSmad2 staining in transgenic dermis included fibroblasts, leukocytes, and endothelial cells (Figure 2P). Furthermore, expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), a Smad2/3 downstream target gene (Goumans et al, 2002), was elevated uniformly in both the epidermis and the dermis (not shown). Another TGFβ1 target gene and TGFβ1-binding protein, decorin (Danielson et al, 1997), was also induced uniformly into the dermis of the transgenic skin (not shown).

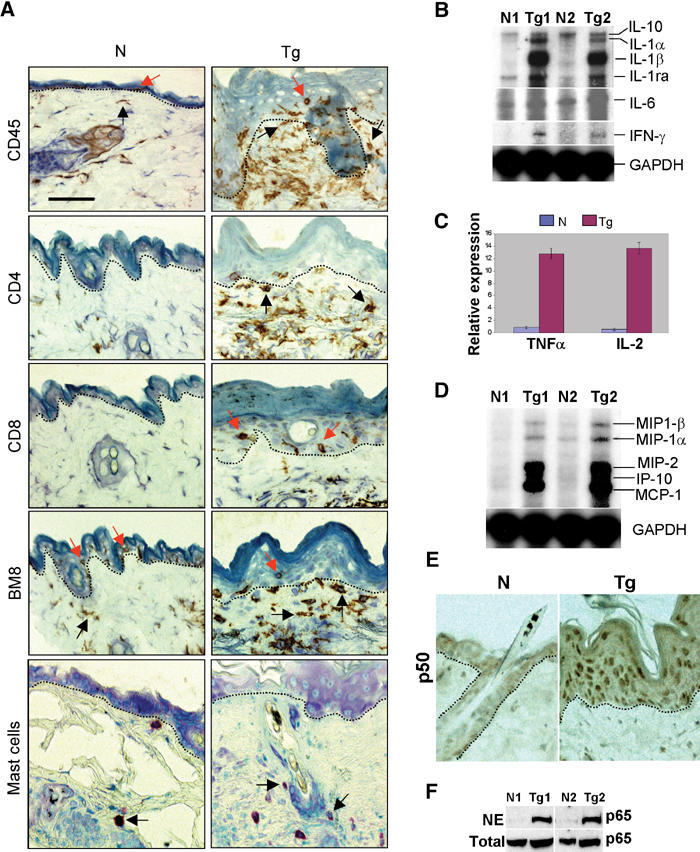

K5.TGFβ1wt skin exhibited inflammatory cell infiltration and elevated inflammatory cytokines and chemokines

We examined the subtypes of inflammatory cells in transgenic and control skins of day 17 (Supplementary data) and 3-month-old mice (Figure 3A). Staining with an anti-mouse CD45 antibody, which recognizes all leukocytes, confirmed the presence of leukocytes in transgenic dermis and epidermis. Staining with the BM8 antibody (Malorny et al, 1986) indicated that the transgenic dermis contained increased numbers of BM8+ macrophages as compared with nontransgenic dermis. Interestingly, BM8+ Langerhans cells (LCs) were present in the nontransgenic epidermis (85±5.1/mm2 epidermis), but were quite sparse in the transgenic epidermis (6.4±2.5/mm2 epidermis, n=5, P<0.01), suggesting a migration of LCs from the epidermis to the dermis in transgenic skin. K5.TGFβ1wt mice also exhibited a significant increase in the numbers of mast cells in the dermis (17±3.6/mm2 dermis) as compared with control skin (3.0±1.2/mm2 dermis, n=5, P<0.01). Although TGFβ1 has been shown to suppress T lymphocyte activation (Letterio and Roberts, 1996), we surprisingly found numerous CD4+ T cells in transgenic skin, predominantly in the superficial dermis. Additionally, scattered CD8+ T cells were found in the transgenic epidermis (Figure 3A). While the K5 promoter does not target transgene expression to nonepithelial immune tissues (Ramirez et al, 1994), it has been shown to target transgene expression at a very low level to thymic epithelia (He et al, 2002). To determine whether T-cell infiltration to transgenic skin was a consequence of T-cell activation in the thymus, we examined thymocytes from mice at 17 p.p. using flow cytometry. At this stage, the thymus is fully developed and differentiated and the transgenic skin exhibited inflammatory cell infiltration (Supplementary data). No differences were found in thymocyte differentiation between transgenic and control mice (Supplementary data). As TGFβ1wt transgene expression was not detectable in thymic epithelia (not shown), TGFβ1wt transgene activation in the skin is likely responsible for T-cell infiltration and activation. Supporting this, integrin αE(CD103)β7, which is not expressed in circulating T cells but is induced by TGFβ1 and required for CD8+ homing to the epidermis (Pauls et al, 2001), was detected in T cells in the epidermis in both day 17 (Supplementary data 1) and 3-month-old transgenic skin (not shown), but not in control epidermis.

Figure 3.

Inflammation in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. N: nontransgenic; Tg: transgenic. (A) Inflammatory cell subtypes. Dotted lines delineate the boundary between the epidermis and the dermis. Examples of leukocytes in the epidermis are pointed by red arrows and in the dermis by black arrows. All sections are counterstained with hematoxylin. (B, C) mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines shown by RPA (B) or real-time RT–PCR (C). (D) RPA for chemokine expression. (E) Immunohistochemistry of NF-κB p50. (F) Western blot revealed significantly increased NF-κB p65 in the nuclear extract (NE) from transgenic skin compared with nontransgenic skin. N1/Tg1 and N2/Tg2 indicate pairs of adult skin samples from nontransgenic and transgenic littermates from the same founder. The bar in the first panel represents 40 μm for all sections in (A) and 60 μm for (E).

Consistent with inflammatory phenotypes, K5.TGFβ1wt skin demonstrated increased levels of mRNA of pro-inflammatory cytokines: interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-2, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Figure 3B and C). Expression of one anti-inflammatory cytokine, the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), which is transcriptionally upregulated by IL-1 (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999), was also elevated in transgenic skin (Figure 3B). In contrast, expression of IL-10, another anti-inflammatory cytokine, remained unchanged in transgenic skin (Figure 3B). K5.TGFβ1wt skin also exhibited significantly elevated expression of five chemokines: macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-2, IFN-inducible protein (IP)-10, and monocyte-chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 (Figure 3D). Furthermore, we examined nuclear translocation of the NF-κB subunits, p50 and p65, an end point of the inflammation cascade (Tak and Firestein, 2001). Immunostaining showed increased nuclear translocation of p50 in both the epidermis and the dermis of transgenic skin (Figure 3E) in comparison to nontransgenic skin. Similarly, Western analysis revealed that, although the total amount of p65 was not altered in transgenic skin, nuclear translocation of p65 was increased in transgenic skin as compared with normal skin (Figure 3F). These results suggest NF-κB activation in transgenic skin.

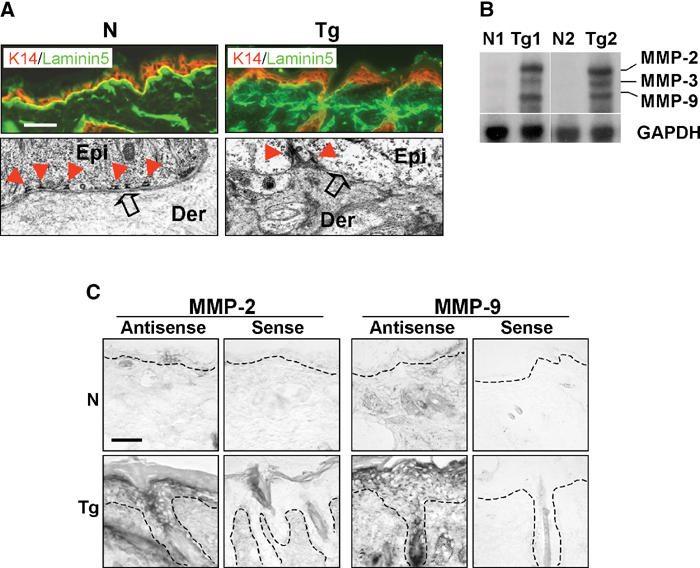

K5.TGFβ1wt skin underwent BM degradation

Notably, the adult K5.TGFβ1wt skin exhibited BM degeneration (not shown). In fact, immunofluorescence on day 10 p.p. transgenic skin exhibited diffuse and discontinuous staining for laminin 5, a BM marker (Fleischmajer et al, 2000), as compared with a fine, continuous pattern of laminin 5 staining in nontransgenic skin (Figure 4A). EM revealed a reduced number of hemidesmosomes and a diminished lamina densa in the BM of transgenic skin (Figure 4A). Consistently, the major matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) responsible for BM degradation, MMP-2, -3, and -9 (Salo et al, 1994), were significantly upregulated in K5.TGFβ1wt skin as compared with normal skin (Figure 4B). In situ hybridization revealed that MMP-2 and -9 expression was upregulated mainly in transgenic epidermis, and to a lesser extent in transgenic dermis (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Impaired BM and upregulated MMPs in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. N: nontransgenic, Tg: transgenic. (A) Immunofluorescence (upper panel) with a laminin 5 antibody (green). A K14 antibody (red) was used as a counterstain. The bar in the first panel represents 40 μm for immunofluorescence sections. The EM pictures (lower panel) are at a magnification of × 24 000. Epi: epidermis, Der: dermis. (B) RPA for expression of MMP-2, -3, and -9 in nontransgenic and transgenic skin (N1/Tg1, N2/Tg2). (C) In situ hybridization on adult skin using anti-sense and sense probes for MMP-2 and MMP-9. The dashed line denotes the boundary between the epidermis and the dermis. The bar in the first panel represents 40 μm for all sections.

K5.TGFβ1wt skin displayed microvascular alterations

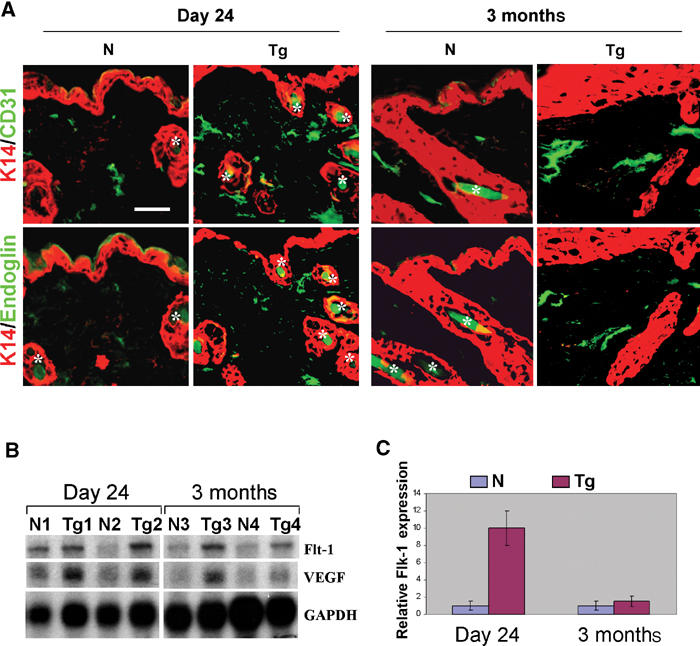

K5.TGFβ1wt skin exhibited prominent angiogenesis prior to the overt inflammation phenotype. Increased angiogenesis in transgenic skin occurred as early as day 7 p.p. (not shown) and peaked at day 24 p.p. (Figure 5A), as determined by staining of an endothelial marker CD31. The number of vessels in day 24 nontransgenic skin was 8±1.6/mm2 dermis, but increased to 30±3.4/mm2 dermis in transgenic skin (n=5, P<0.01). At 3 months of age, the number of vessels in K5.TGFβ1wt skin was similar to that in nontransgenic skin (24±2.5 vs 18±1.9/mm2 dermis, n=5). However, the vessels in 3-month-old transgenic skin were enlarged as compared with those in nontransgenic skin (Figure 5A), demonstrated by a larger dermal area covered by vessels (23±1.3 vs 9.2±0.81%, n=5, P<0.05). In addition, the number of vessels stained for endoglin, an accessory TGFβ receptor that is predominantly expressed in proliferating endothelial cells (Rulo et al, 1995), was increased from 7.2±1.7/mm2 dermis in control skin to 24±3.9/mm2 dermis in transgenic skin at day 24 (n=5, P<0.01), and from 12±2.4/mm2 dermis in control skin to 21±4.1/mm2 dermis in transgenic skin at 3 months of age (n=5, P<0.01, Figure 5A). This result suggests that, although the numbers of CD31-positive vessels were similar between transgenic and nontransgenic skin at 3 months p.p., there were more proliferating endothelial cells in transgenic vessels. Consistent with increased angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor, Flt-1, were upregulated approximately two- to three-fold in K5.TGFβ1wt skin compared with normal skin (Figure 5B). Another VEGF receptor, Flk-1, which has a more potent angiogenesis effect than Flt-1 (Shibuya, 2003), was elevated by nine-fold in day 24 transgenic skin compared with control skin, and its expression returned to normal by 3 months of age (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Angiogenesis in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. N: nontransgenic; Tg: transgenic. (A) Immunofluorescence staining for CD31 and endoglin (green). Sections were counterstained with a K14 antibody (red). Asterisks denote hair shafts, that exhibit autofluorescence. The bar in the first panel represents 40 μm for all sections. (B) RPA results for expression of VEGF and Flt-1 in the skin from day 24 (N1/Tg1, N2/Tg2) and 3-month-old mice (N3/Tg3, N4/Tg4). (C) Expression of Flk-1 by real-time RT–PCR.

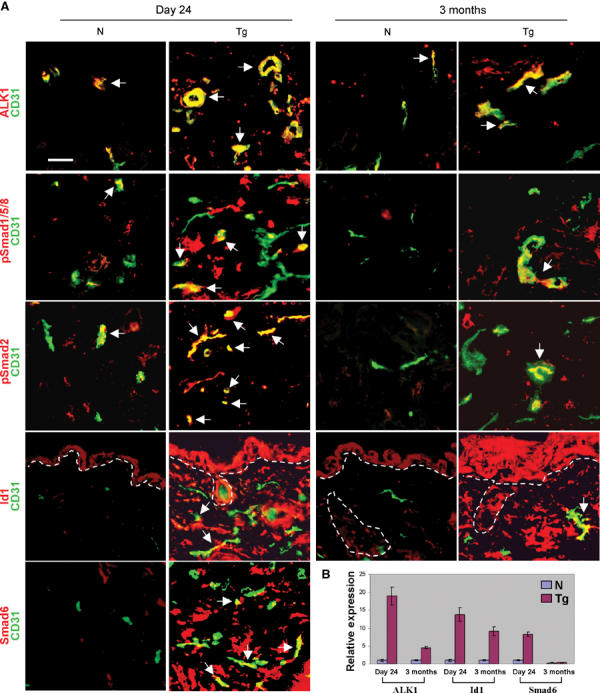

Recent studies suggest that TGFβ1 regulates angiogenesis via a delicate balance between ALK1 and ALK5 signaling (Goumans et al, 2002). To determine whether increased angiogenesis in TGFβ1wt transgenic skin represented a shift in the balance between these two pathways, we examined the expression patterns of ALK1, ALK5, and their downstream Smads on day 24 and 3-month-old control and transgenic skin (Figure 6). ALK1 exhibited stronger staining in the vessels of both day 24 and 3-month-old transgenic skins than control skins (Figure 6A), and its expression levels increased by 20- and 4.5-fold in day 24 and 3-month transgenic skin, respectively, in comparison with the age-matched nontransgenic skin (n=5, P<0.01, Figure 6B). Consistent with our previous observations (He et al, 2002), ALK5 was expressed at a much lower level in capillary vessels in the superficial dermis as compared with the epidermis, and the staining patterns did not differ between control and transgenic skin (not shown). An antibody that recognizes phosphorylated Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8 (pSmad1/5/8) stained 20±3.0% of vessels in day 24 transgenic skin vs 1±0.2% in nontransgenic skin (n=5, P<0.01, Figure 6). In 3-month-old transgenic skin, the number of pSmad1/5/8-positive vessels was reduced to 5±0.9% (n=5), which was still significantly higher than those in control skin (1±0.3%, n=5, P<0.01, Figure 6A). In addition, staining of pSmad1/5/8 was increased in other dermal cells in transgenic skin (Figure 6A), but was not altered in transgenic epidermis, in comparison with nontransgenic skin (not shown). In transgenic skin, pSmad2 stained 90±8.9% (n=5) of vessels at day 24 and 40±3.6% (n=5) at 3 months of age, significantly higher than 4.8±0.90 and 4.9±0.80%, respectively, in age-matched nontransgenic skin (n=5, P<0.01, Figure 6A). Staining for inhibitor of differentiation (Id)1, the product of a Smad1/Smad5 target gene that promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration (Miyazono and Miyazawa, 2002), was positive in vessels of day 24 and 3-month-old transgenic skin, but not in vessels of control skin at either ages (Figure 6A). Consistent with previous reports that Id1 expression is increased in the epidermis and inflammatory cells in psoriatic skin (Bjorntorp et al, 2003) or inflammation (Coppe et al, 2003), transgenic epidermis and dermis also exhibited increased Id1 staining as compared with control skin (Figure 6A). Id1 expression levels increased by 13- and 10-fold in day 24 and 3-month transgenic skin, respectively, in comparison with the age-matched nontransgenic skin (n=5, P<0.01, Figure 6B). In addition, expression of Smad6, another Smad1/Smad5 target gene (Ishida et al, 2000), was elevated by seven-fold in day 24 transgenic skin compared with control skin, but was not detectable in 3-month-old nontransgenic and transgenic skin (Figure 6B). The Smad6 staining pattern correlated with that of pSmad1/Smad5. The expression of Smad7, which is Smad2/3 downstream target, was moderately elevated in transgenic vessels at both ages (not shown).

Figure 6.

Expression of TGFβ signaling components in the skin. N: nontransgenic, Tg: transgenic. (A) Immunofluorescence was counterstained with a CD31 antibody (green). Dotted lines denote the border between the epidermis/hair follicles and the dermis. Arrows point out representative vessels with double fluorescence (yellow or orange). Note: pSmad1/5/8, pSmad2, Id1, and Smad6 antibodies also stained some non-endothelial cells (red) in the dermis, and Id1 was also in the epidermis. The bar in the first panel represents 40 μm for all sections. (B) Expression of ALK1, Id1, and Smad6 in the skin by real-time RT–PCR.

TGFβ1wt transgene expression only induced epidermal hyperproliferation in vivo

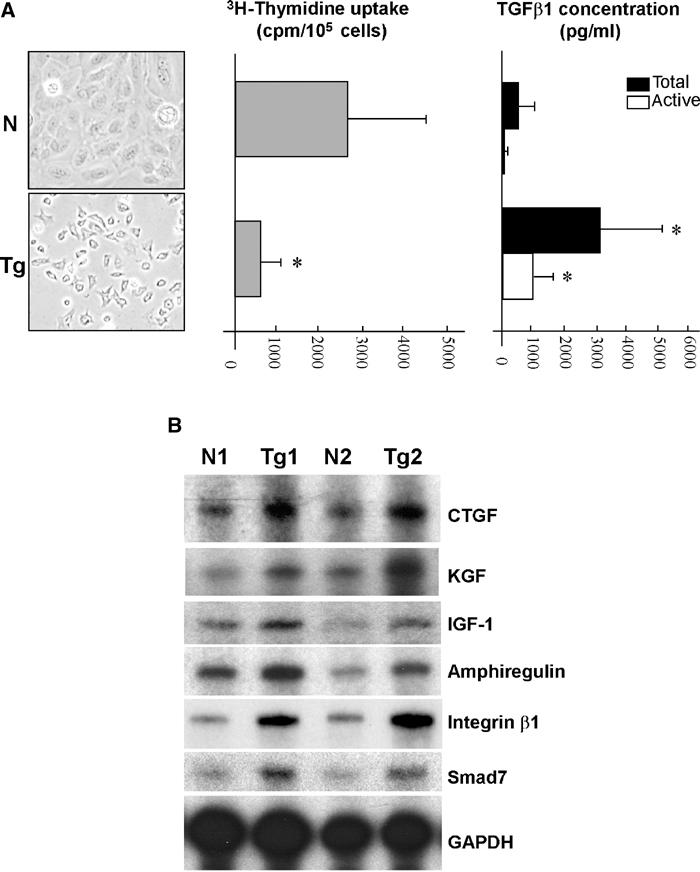

To analyze the direct effect of the TGFβ1wt transgene on keratinocyte proliferation, we isolated keratinocytes from 3-month-old control and transgenic skin and plated the same number of cells under culture conditions that maintain them in a proliferative state (Wang et al, 1997). By 72 h, control keratinocytes reached confluency, whereas transgenic keratinocytes reached only about 40% confluency (Figure 7A). 3H-Thymidine (3H-TdR) uptake in transgenic keratinocytes was 600±195 cpm/105 cells (n=3), a dramatic decrease in comparison with wild-type keratinocytes (2599±1103 cpm/105 cells, n=3, P<0.01, Figure 7A). Growth inhibition correlated with an increased level of TGFβ1 secreted by transgenic keratinocytes. The amount of total TGFβ1 protein in the culture media was 3098±1103 pg/ml from transgenic keratinocytes, but 486±43 pg/ml from control cells (n=3, P<0.01). The level of active TGFβ1 protein in the media of cultured transgenic keratinocytes was 805±287 pg/ml, but was only 67±12 pg/ml in the media of cultured nontransgenic keratinocytes (n=3, P<0.01) (Figure 7A). To determine whether transgenic dermis produced growth factors that override the growth inhibitory effect of TGFβ1 on keratinocytes in vivo, we examined several fibroblast-produced growth factors. Consistent with a growth-stimulatory effect of TGFβ1 on dermal fibroblasts, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a fibroblast activation marker that is a TGFβ1 transcriptional target (Duncan et al, 1999), was significantly upregulated in the transgenic skin as compared with nontransgenic skin (Figure 7B). In addition, K5.TGFβ1wt skin showed a two- to four-fold increase in expression of keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) as compared with nontransgenic skin (Figure 7B). Additionally, expression of amphiregulin, an IGF-1 target gene in keratinocytes (Vaday and Lider, 2000), increased two- to three-fold in transgenic skin as compared with nontransgenic skin (Figure 7B). Interestingly, K5.TGFβ1wt skin also demonstrated a four- to five-fold increase in integrin β1 expression (Figure 7B), which has also been shown to play a role in stimulating keratinocyte hyperproliferation in human psoriatic epidermis (Haase et al, 2001b). Finally, Smad7, a TGFβ1 target gene that stimulates keratinocyte proliferation (He et al, 2002), was upregulated two- to three-fold in transgenic skin (Figure 7B), in both the epidermis and the dermis (not shown).

Figure 7.

TGFβ1-mediated growth inhibition is overcome in the presence of the dermis. N: nontransgenic, Tg: transgenic. (A) Cultured keratinocytes (left panel) 72 h after plating. Decreased 3H-thymidine uptake in transgenic cells compared with nontransgenic cells (middle panel) correlated with a significantly higher level of both latent and active forms of TGFβ1 (right panel). Data represent mean value±s.d. from three to five cultures. *P<0.01. (B) mRNA levels of growth regulators. Representative results shown here are from two pairs of nontransgenic/transgenic (N1/Tg1, N2/Tg2) adult skin samples.

Discussion

TGFβ1 overexpression, together with subsequent molecular changes, leads to a psoriasis-like skin inflammation

It is well documented that TGFβ1 is one of the most potent chemotactic cytokines for leukocytes (Wahl, 1999). However, at later stages of inflammation, TGFβ1 usually inhibits the functions of the activated leukocytes (Wahl, 1999). Studies from TGFβ1 knockout mice implicate that TGFβ1 plays a role in immunosuppression and anti-inflammation in vivo (Shull et al, 1992; Letterio and Roberts, 1996). Thus, it was a surprise to us that K5.TGFβ1wt skin developed such a massive inflammation. The progressive inflammation in K5.TGFβ1wt skin may be due to constitutive TGFβ1 overexpression, which destroys the balance between the activation and de-activation of leukocytes, thereby causing unresolved inflammation (Wahl, 1999). Additionally, inflammatory cytokines and chemokines released from transgenic keratinocytes and inflammatory cells (see details below) may be able to override any inhibitory effect of TGFβ1 on inflammation, particularly on T-cell activation. Interestingly, although TGFβ1 null mice exhibit inflammation in many organs, skin inflammation in these mice is not reported (Letterio and Roberts, 1996). Thus, TGFβ1 may not exert a strong immune-suppressive effect on the skin. Alternatively, immune suppression of TGFβ1 may be more easily overcome in the skin than in other organs, as keratinocytes can produce many inflammatory cytokines and chemokines under pathological conditions.

The increased levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α in transgenic skin are consistent with a Th1 inflammatory response (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999). In addition, the lack of production of IL-4, the hallmark Th2 cytokine, distinguishes the skin disorder in K5.TGFβ1wt mice from Th2 skin inflammatory diseases, for example, allergic contact dermatitis and atopic dermatitis (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999). It has been shown that upregulation of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α precedes other cytokines and chemokines in psoriatic lesions (Uyemura et al, 1993). IL-1 and TNFα activate the NF-κB pathway and subsequently induce further expression of IL-1 and IL-6, chemokines, growth factors, adhesion molecules, and integrins such as integrin β1 (Haase et al, 2001b; Tak and Firestein, 2001). Induction of all these molecules can be further synergistically augmented by TNF-α and IFN-γ (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999). Particularly, MIP-2 (IL-8 in humans (Shanley et al, 1997)) is a strong chemoattractant for neutrophils and T cells, and is mainly produced by keratinocytes upon stimulation by inflammatory cytokines (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999). In addition to MIP-2, four other chemokines upregulated in K5.TGFβ1wt skin, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IP-10, and MCP-1, provide a strong T-cell chemotactic effect (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999). MCP-1 also confers chemotactic effects on monocytes/macrophages and its expression in the dermis may be responsible for a chemotactic effect on monocytes/macrophages, resulting in a reduced number of epidermal LCs in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. Interestingly, the depletion of epidermal LCs has also been observed in human psoriatic skin (Christophers and Mrowietz, 1998).

The psoriasis-like phenotypes in K5.TGFβ1wt skin are likely facilitated by TGFβ1-induced BM degradation. Epidermal BM defects and increased expression of MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 in the epidermis have been linked to human psoriasis (Fleischmajer et al, 2000; Suomela et al, 2001). As both MMP-2 and -9 have been shown to activate latent TGFβ1 (Yu and Stamenkovic, 2000), increased expression of MMPs in K5.TGFβ1wt skin may further activate TGFβ1 and thus contribute to the deteriorated skin phenotypes in K5.TGFβ1wt mice. As a consequence of BM degradation, TGFβ1, along with other keratinocyte-derived cytokines/chemokines, can be more easily secreted into the dermis to exert paracrine effects on inflammation and angiogenesis. Accordingly, growth factors/cytokines produced from dermal fibroblasts and inflammatory cells would also be more easily delivered to the epidermis, which could subsequently induce epidermal hyperplasia. Finally, leukocyte migration towards the epidermis may also be facilitated by BM degradation.

TGFβ1-induced angiogenesis represents synergistic effects of TGFβ1 and subsequent molecular alterations

The early-onset angiogenesis and vasodilatation observed in K5.TGFβ1wt skin suggests that microvascular alterations play an important role in the initiation of psoriasis-like inflammatory disorder. Particularly, such alterations would facilitate in vivo leukocyte infiltration and epidermal hyperproliferation. In return, leukocytes and keratinocytes produce angiogenesis factors that further contribute to microvascular alterations.

TGFβ1 promotes angiogenesis via ALK1 signaling and inhibits angiogenesis via ALK5 signaling (Goumans et al, 2002). Our results suggested that both ALK1 and ALK5 pathways were activated in the vessels of transgenic skin. However, increased ALK1 and pSmad1/5/8 in transgenic vessels was more obvious at day 24 p.p. when angiogenesis peaked in transgenic skin. This result is consistent with previous reports that ALK1 expression is elevated during angiogenesis and Smad1/5 phosphorylation only occurs transiently in the active phase of angiogenesis (Goumans et al, 2002). Although ALK5-Smad2/Smad3 activation in endothelial cells has a direct inhibitory effect on endothelial proliferation and migration (Goumans et al, 2003b), activation of this pathway is also essential for the activation of the ALK1-Smad1/Smad5 pathway (Lamouille et al, 2002; Goumans et al, 2003b). In addition, elevated expression of endoglin in transgenic vessels may help to shift the effect of TGFβ1 on angiogenesis from inhibition to promotion. Endoglin has been shown to be upregulated by ALK1 and counteract the inhibitory effect of ALK5 on angiogenesis (Goumans et al, 2003a). Thus, the combination of these molecular alterations may directly promote angiogenesis at an early stage. At a later stage (e.g., 3 months of age), when pSmad1/5/8 was reduced, constant Smad2/Smad3 activation in transgenic vessels might shift microvascular structure towards a remodeling state, which was evident in our model as angiogenesis decreased but vessel size increased at 3 months of age. Although TGFβ1wt also induced the expression of downstream antagonists Smad6 and Smad7, as well as molecules that potentially inhibit angiogenesis, for example, PAI-1 and decorin, their expression appeared to be insufficient to block completely the effect of TGFβ1 on angiogenesis at the early stage.

In addition to the direct effect of TGFβ1 on endothelial cells, microvascular alterations in K5.TGFβ1wt skin may reflect the synergistic effects of increased expression of VEGF, MMPs, growth factors/cytokines, and chemokines, which play important roles in angiogenesis. Particularly, expression of Flk-1, a VEGF receptor that plays a more potent angiogenesis role than Flt-1 (Shibuya, 2003), was significantly elevated at the active angiogenesis phase in K5.TGFβ1wt skin. VEGF has been shown to play a central role in vascular alterations in human psoriasis (Christophers and Mrowietz, 1998), and VEGF transgenic mice develop psoriasis-like lesions (Xia et al, 2003). Thus, VEGF and its receptors may be one of the important targets of TGFβ1 that mediate TGFβ1-induced inflammatory skin lesions. As TGFβ1-induced lesions are more severe than those in VEGF transgenic skin, other molecular changes in K5.TGFβ1wt skin apparently participated in the development of the overt inflammatory lesions. For instance, increased expression of MMPs and CTGF in K5.TGFβ1wt skin may also contribute to angiogenesis (Moussad and Brigstock, 2000; Bauvois, 2004). When skin inflammation becomes prominent, multiple inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, for example, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1, which can also induce angiogenesis (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999; Low et al, 2001), may contribute to angiogenesis observed in K5.TGFβ1wt skin.

Epidermal hyperproliferation in K5.TGFβ1wt skin is a secondary effect of other skin phenotypes

Although TGFβ1 is considered as a potent keratinocyte growth inhibitor, transgenic mouse models expressing TGFβ1 in different compartments of the epidermis exhibited either keratinocyte growth inhibition or keratinocyte hyperproliferation. The mechanisms underlying these contradictory data are largely unknown. Our study suggests that in vivo epidermal hyperproliferation in K5.TGFβ1wt skin is a secondary effect. Increased inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in K5.TGFβ1wt skin, such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, which promote keratinocyte proliferation (Bonifati and Ameglio, 1999), can be produced by both keratinocytes and inflammatory cells. Other keratinocyte-produced factors, for example, integrin β1 and Smad7, also promote epidermal proliferation (Carroll et al, 1995; Haase et al, 2001a; He et al, 2002). However, as keratinocyte hyperproliferation in K5.TGFβ1wt skin occurs only in vivo, expression of positive growth regulators by transgenic keratinocytes appears to be a secondary effect that requires the presence of the dermis. In addition to inflammatory cells, fibroblasts in transgenic skin may greatly contribute to epidermal hyperproliferation. It has been shown that psoriatic fibroblasts induce hyperproliferation of normal keratinocytes (Miura et al, 2000). Among fibroblast-produced growth factors, KGF and IGF-1 directly stimulate keratinocyte hyperproliferation (Miura et al, 2000). IGF-1 also stimulates expression of amphiregulin, which, upon activation, stimulates keratinocyte proliferation (Vaday and Lider, 2000).

In summary, we show that TGFβ1wt overexpression induced or recruited many molecules involved in psoriasis pathogenesis. This fact may explain why K5.TGFβ1wt mice exhibited more severe psoriasis-like phenotypes than previous transgenic mice that target individual growth factors or cytokines in the skin (Schon, 1999). Of particular interest, the amount of TGFβ1 protein in K5.TGFβ1wt skin was equivalent to the peak level of TGFβ1 in normal mouse skin undergoing wound healing. This indicates that a physiologically relevant dose of TGFβ1 may be sufficient to participate in the development of a psoriasis-like inflammatory skin disorder.

Materials and methods

Generation and identification of K5.TGFβ1wt mice

The ∼1.6 kb full-length wild-type human TGFβ1 cDNA (TGFβ1wt) was inserted into the K5 expression vector (He et al, 2002). The K5.TGFβ1wt transgene was microinjected into the pronuclei of mouse embryos obtained from ICR female mice mated to B6D2 male mice. Mice were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail DNA-utilizing primers specific for TGFβ1wt (sequences in Supplementary data 1). Throughout this study, all transgenic mice were heterozygous, and at least three independent analyses were performed for each assay, using three to five samples in each group.

Tissue histology, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry

Skin histology was visualized with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry were performed on frozen sections as previously described (Wang et al, 1999). EM on skin samples was performed as previously described (Sellheyer et al, 1993). Toluidine blue was used to stain mast cells (Xia et al, 2003). Immunofluorescence was performed using antibodies against K6 (He et al, 2002), laminin 5 (RDI), CD31, endoglin (BD Biosciences), ALK1 (R&D Systems), ALK5, pSmad1/5/8, pSmad2 (Cell Signaling), and Id1 (Santa Cruz). In vivo BrdU labeling and detection were performed as previously described (He et al, 2002). The antibodies used in immunohistochemistry included NF-κB p50 (Santa Cruz), active and LAP TGFβ1 (R&D Systems). Leukocyte subtypes were identified using primary antibodies CD45, CD4, and CD8 (BD Biosciences), and the BM8 antibody (BMA Biomedicals). Biotinylated secondary antibodies were used in conjunction with an avidin-peroxidase reagent (VECTASTAIN®) and visualized using diaminobenzidine (Sigma). The MetaMorph® software (Universal Imaging Corporation™) was used for quantitative measurements of microscopy images (mean±s.d.).

Keratinocyte culture and 3H-TdR incorporation

Primary keratinocytes were isolated and cultured from adult ear skin as described (Beg and Baldwin, 1993; Wang et al, 1997). At 24 h after plating, the cells were fed with fresh medium with 0.05 mM Ca2+ to maintain proliferation. Cell proliferation rates were determined by 3H-TdR uptake as previously described (Wang et al, 1997).

TGFβ1 ELISA

A TGFβ1-specific ELISA kit (R&D Systems) was used to quantify levels of TGFβ1. Protein samples were acidified with 1 N HCl and neutralized with 1.2 N NaOH/0.5 M HEPES to assay for the amount of total (i.e., the sum of latent and active) TGFβ1 protein. The concentration of active TGFβ1 protein was analyzed on samples that were not acidified.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization for MMP-2 and -9 was performed on frozen sections as previously described (He et al, 2001).

RNA isolation and analysis

Skin RNA was extracted using RNAzol-B (Tel-Test), and RPAs were performed using RPA II™ kits (Ambion) as previously described (Wang et al, 1999). 32P-labeled riboprobes were synthesized utilizing individual probes for VEGF, Flt-1, and IGF-1 or multiprobe sets for inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and MMPs (BD Biosciences). The mouse integrin β1 (Waikel et al, 2001) and Smad7 (He et al, 2001) probes were synthesized as previously described. Primers specific for mouse amphiregulin, CTGF, and KGF (sequences in Supplementary data) were used to amplify cDNA fragments by RT–PCR. The subsequent products were subcloned into a pGEM®-T Easy vector (Promega) and linearized for RPA probe synthesis. A 32P-GAPDH riboprobe was included as a loading control in each assay. The intensity of the protected bands was determined by densitometric scanning of X-ray films, and quantified by the intensity of each detected signal over that of GAPDH. Real-time RT–PCR was performed to detect TNFα, IL-2, Flk-1, ALK1, Id1, and Smad6 using Taqman® Assays-on-Demand™ probes (Applied Biosystems). An 18S probe was included as an internal control. The relative RNA expression levels were calculated by using the Comparative CT Method, and results from three to five samples in each group were averaged.

Western blot analysis

Total skin protein and nuclear extract were extracted as previously described (Schreiber et al, 1989; He et al, 2002). Western blot analysis using a goat anti-NF-κB p65 (Santa Cruz) was performed as described (Wang et al, 1997).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry for thymocytes was performed, and data were analyzed as previously described (He et al, 2002).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Jose Jorcano for providing the K5 vector, Dr Cliff White for pathological evaluation of K5.TGFβ1wt skin phenotypes, and Drs Jon Hanifin and Andrew Blauvelt for critically reading this manuscript. This research was supported by NIH grants CA79998 and CA87849 to X-J Wang and NIH grant GM63773 to X-H Feng.

References

- Bauvois B (2004) Transmembrane proteases in cell growth, invasion: new contributors to angiogenesis? Oncogene 23: 317–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Baldwin AS Jr (1993) The I kappa B proteins: multifunctional regulators of Rel/NF-kappa B transcription factors. Genes Dev 7: 2064–2070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorntorp E, Parsa R, Thornemo M, Wennberg AM, Lindahl A (2003) The helix–loop–helix transcription factor Id1 is highly expressed in psoriatic involved skin. Acta Derm Venereol 83: 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati C, Ameglio F (1999) Cytokines in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 38: 241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner AM, Marquardt H, Malacko AR, Lioubin MN, Purchio AF (1989) Site-directed mutagenesis of cysteine residues in the pro region of the transforming growth factor beta 1 precursor—expression, characterization of mutant proteins. J Biol Chem 264: 13660–13664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JM, Romero MR, Watt FM (1995) Suprabasal integrin expression in the epidermis of transgenic mice results in developmental defects, a phenotype resembling psoriasis. Cell 83: 957–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophers E, Mrowietz U (1998) Psoriasis. In Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine, Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Fitzpatrick TB (eds), pp 495–521. New York: McGraw-Hill [Google Scholar]

- Coppe JP, Smith AP, Desprez PY (2003) Id proteins in epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res 285: 131–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W, Fowlis DJ, Cousins FM, Duffie E, Bryson S, Balmain A, Akhurst RJ (1995) Concerted action of TGF-beta 1 and its type II receptor in control of epidermal homeostasis in transgenic mice. Genes Dev 9: 945–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV (1997) Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol 136: 729–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MR, Frazier KS, Abramson S, Williams S, Klapper H, Huang X, Grotendorst GR (1999) Connective tissue growth factor mediates transforming growth factor beta-induced collagen synthesis: down-regulation by cAMP. FASEB J 13: 1774–1786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmajer R, Kuroda K, Hazan R, Gordon RE, Lebwohl MG, Sapadin AN, Unda F, Iehara N, Yamada Y (2000) Basement membrane alterations in psoriasis are accompanied by epidermal overexpression of MMP-2 and its inhibitor TIMP-2. J Invest Dermatol 115: 771–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowlis DJ, Cui W, Johnson SA, Balmain A, Akhurst RJ (1996) Altered epidermal cell growth control in vivo by inducible expression of transforming growth factor beta 1 in the skin of transgenic mice. Cell Growth Differ 7: 679–687 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans MJ, Lebrin F, Valdimarsdottir G (2003a) Controlling the angiogenic switch: a balance between two distinct TGF-b receptor signaling pathways. Trends Cardiovasc Med 13: 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Lebrin F, Larsson J, Mummery C, Karlsson S, Ten Dijke P (2003b) Activin receptor-like kinase (ALK)1 is an antagonistic mediator of lateral TGFbeta/ALK5 signaling. Mol Cell 12: 817–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Rosendahl A, Sideras P, Ten Dijke P (2002) Balancing the activation state of the endothelium via two distinct TGF-beta type I receptors. EMBO J 21: 1743–1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase I, Hobbs RM, Romero MR, Broad S, Watt FM (2001a) A role for mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by integrins in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. J Clin Invest 108: 527–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase I, Hobbs RM, Romero MR, Broad S, Watt FM (2001b) A role for mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by integrins in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. J Clin Invest 108: 527–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Cao T, Smith DA, Myers TE, Wang XJ (2001) Smads mediate signaling of the TGFbeta superfamily in normal keratinocytes but are lost during skin chemical carcinogenesis. Oncogene 20: 471–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Li AG, Wang D, Han S, Zheng B, Goumans MJ, ten Dijke P, Wang XJ (2002) Overexpression of Smad7 results in severe pathological alterations in multiple epithelial tissues. EMBO J 21: 2580–2590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida W, Hamamoto T, Kusanagi K, Yagi K, Kawabata M, Takehara K, Sampath TK, Kato M, Miyazono K (2000) Smad6 is a Smad1/5-induced smad inhibitor. Characterization of bone morphogenetic protein-responsive element in the mouse Smad6 promoter. J Biol Chem 275: 6075–6079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn H, Nielsen EH, Elberg JJ, Bierring F, Ronne M, Brandrup F (1988) Ultrastructure of psoriatic epidermis. APMIS 96: 723–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamouille S, Mallet C, Feige JJ, Bailly S (2002) Activin receptor-like kinase 1 is implicated in the maturation phase of angiogenesis. Blood 100: 4495–4501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence DA (1991) Identification activation of latent transforming growth factor beta. Methods Enzymol 198: 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letterio JJ, Roberts AB (1996) Transforming growth factor-beta1-deficient mice: identification of isoform-specific activities in vivo. J Leukoc Biol 59: 769–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Alexander V, Vijayachandra K, Bhogte E, Diamond I, Glick A (2001) Conditional epidermal expression of TGFbeta 1 blocks neonatal lethality but causes a reversible hyperplasia alopecia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 9139–9144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low QE, Drugea IA, Duffner LA, Quinn DG, Cook DN, Rollins BJ, Kovacs EJ, DiPietro LA (2001) Wound healing in MIP-1alpha(−/−) and MCP-1(−/−) mice. Am J Pathol 159: 457–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malorny U, Michels E, Sorg C (1986) A monoclonal antibody against an antigen present on mouse macrophages absent from monocytes. Cell Tissue Res 243: 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura H, Sano S, Higashiyama M, Yoshikawa K, Itami S (2000) Involvement of insulin-like growth factor-I in psoriasis as a paracrine growth factor: dermal fibroblasts play a regulatory role in developing psoriatic lesions. Arch Dermatol Res 292: 590–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Kusanagi K, Inoue H (2001) Divergence convergence of TGF-beta/BMP signaling. J Cell Physiol 187: 265–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Miyazawa K (2002) Id: a target of BMP signaling. Sci STKE 2002: E40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussad EE, Brigstock DR (2000) Connective tissue growth factor: what's in a name? Mol Genet Metab 71: 276–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff BJ, Naidu Y (1994) Perturbation of epidermal barrier function correlates with initiation of cytokine cascade in human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 30: 535–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff BJ, Wrone-Smith T (1999) Injection of pre-psoriatic skin with CD4+ T cells induces psoriasis. Am J Pathol 155: 145–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls K, Schon M, Kubitza RC, Homey B, Wiesenborn A, Lehmann P, Ruzicka T, Parker CM, Schon MP (2001) Role of integrin alphaE(CD103)beta7 for tissue-specific epidermal localization of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Invest Dermatol 117: 569–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez A, Bravo A, Jorcano JL, Vidal M (1994) Sequences 5′ of the bovine keratin 5 gene direct tissue–cell-type-specific expression of a lacZ gene in the adult during development. Differentiation 58: 53–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulo HF, Westphal JR, van de Kerkhof PC, de Waal RM, van Vlijmen IM, Ruiter DJ (1995) Expression of endoglin in psoriatic involved uninvolved skin. J Dermatol Sci 10: 103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo T, Makela M, Kylmaniemi M, Autio-Harmainen H, Larjava H (1994) Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2–9 during early human wound healing. Lab Invest 70: 176–182 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon MP (1999) Animal models of psoriasis—what can we learn from them? J Invest Dermatol 112: 405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber E, Matthias P, Muller MM, Schaffner W (1989) Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts' prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res 17: 6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellheyer K, Bickenbach JR, Rothnagel JA, Bundman D, Longley MA, Krieg T, Roche NS, Roberts AB, Roop DR (1993) Inhibition of skin development by overexpression of transforming growth factor beta 1 in the epidermis of transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 5237–5241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley TP, Schmal H, Warner RL, Schmid E, Friedl HP, Ward PA (1997) Requirement for C–X–C chemokines (macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant) in IgG immune complex-induced lung injury. J Immunol 158: 3439–3448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya M (2003) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: its unique signaling and specific ligand, VEGF-E. Cancer Sci 94: 751–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D (1992) Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 359: 693–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomela S, Kariniemi AL, Snellman E, Saarialho-Kere U (2001) Metalloelastase (MMP-12) and 92-kDa gelatinase (MMP-9) as well as their inhibitors, TIMP-1 and -3, are expressed in psoriatic lesions. Exp Dermatol 10: 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak PP, Firestein GS (2001) NF-kappaB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest 107: 7–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyemura K, Yamamura M, Fivenson DF, Modlin RL, Nickoloff BJ (1993) The cytokine network in lesional lesion-free psoriatic skin is characterized by a T-helper type 1 cell-mediated response. J Invest Dermatol 101: 701–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaday GG, Lider O (2000) Extracellular matrix moieties cytokines, enzymes: dynamic effects on immune cell behavior inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 67: 149–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl SM (1999) TGF-beta in the evolution resolution of inflammatory immune processes. Introduction. Microbes Infect 1: 1247–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waikel RL, Kawachi Y, Waikel PA, Wang XJ, Roop DR (2001) Deregulated expression of c-Myc depletes epidermal stem cells. Nat Genet 28: 165–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield LM, Winokur TS, Hollands RS, Christopherson K, Levinson AD, Sporn MB (1990) Recombinant latent transforming growth factor beta 1 has a longer plasma half-life in rats than active transforming growth factor beta 1, a different tissue distribution. J Clin Invest 86: 1976–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XJ, Greenhalgh DA, Bickenbach JR, Jiang A, Bundman DS, Krieg T, Derynck R, Roop DR (1997) Expression of a dominant-negative type II transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) receptor in the epidermis of transgenic mice blocks TGF-beta-mediated growth inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 2386–2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XJ, Liefer KM, Tsai S, O'Malley BW, Roop DR (1999) Development of gene-switch transgenic mice that inducibly express transforming growth factor beta1 in the epidermis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 8483–8488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia YP, Li B, Hylton D, Detmar M, Yancopoulos GD, Rudge JS (2003) Transgenic delivery of VEGF to the mouse skin leads to an inflammatory condition resembling human psoriasis. Blood 102: 161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Chan T, Demare J, Iwashina T, Ghahary A, Scott PG, Tredget EE (2001) Healing of burn wounds in transgenic mice overexpressing transforming growth factor-beta 1 in the epidermis. Am J Pathol 159: 2147–2157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Stamenkovic I (2000) Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-beta promotes tumor invasion angiogenesis. Genes Dev 14: 163–176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials