Abstract

We aimed to compare the recommendations of the Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder 2012 (KMAP-DD 2012) with other recently published treatment guidelines for depressive disorder. We reviewed a total of five recently published global treatment guidelines and compared each treatment recommendation of the KMAP-DD 2012 with those in other guidelines. For initial treatment recommendations, there were no significant major differences across guidelines. However, in the case of nonresponse or incomplete response to initial treatment, the second recommended treatment step varied across guidelines. For maintenance therapy, medication dose and duration differed among treatment guidelines. Further, there were several discrepancies in the recommendations for each subtype of depressive disorder across guidelines. For treatment in special populations, there were no significant differences in overall recommendations. This comparison identifies that, by and large, the treatment recommendations of the KMAP-DD 2012 are similar to those of other treatment guidelines and reflect current changes in prescription pattern for depression based on accumulated research data. Further studies will be needed to address several issues identified in our review.

Keywords: Depressive disorder, Pharmacotherapy, Algorithm, Treatment guideline, KMAP-DD 2012

INTRODUCTION

Depressive disorder is characterized by various symptom and recurrence patterns which cause personal or socio-economical loss and impairment in social functioning and productivity.1 Since the introduction of tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), pharmacotherapy, including antidepressants, has been the mainstay treatment for depressive disorder.2 Since the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and newer antidepressants of various mechanisms, the use of medication in clinical practice has increased. Consequently, there have been many changes in the treatment of depression. However, despite such progress in the pharmacotherapy of depression, a high percentage of patients who are treated with adequate pharmacotherapy still do not achieve symptom remission.3-5 Thus, there have been many therapeutic efforts to improve treatment outcome for treatment-resistant depression.6-10 Additionally, new findings related to the treatment of depression in special populations such as the elderly, children/adolescents, and women have been achieved.11-16

Because there are frequently new findings related to the pharmacotherapy of depression, and there are many factors to be considered when choosing a treatment strategy, the development of treatment guidelines for clinicians is very important. To meet this clinical need, many treatment guidelines for depression have been published.17-21 However, the use of available guidelines may be limited at times due to cultural differences in clinical environments and medical situations as well as culture-specific needs of clinicians and patients. Thus, it is necessary to develop guidelines that can more aptly respond to cultural issues and specifics in different countries. In Korea, the Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Major Depressive Disorder was published in 2002 by gathering the opinions of Korean experts in the treatment of depression (KMAP-MD 2002).22 In 2006, a revision to the Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder was released (KMAP-DD 2006).23 Over the past six years, newer antidepressants have been introduced for the treatment of depression, and the antidepressant effect of atypical antipsychotics has been demonstrated.24-26 To reflect the current changes in treatment strategies for depression, we revised the previous algorithm and published the Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder in 2012 (KMAP-DD 2012).27 In the present paper, we aimed to compare the recommendations of the KMAP-DD 201227 with those of other global treatment guidelines that have been recently published and used. By identifying similarities and differences across treatment guidelines, we aimed to identify the drawbacks of the KMAP-DD 201227 that may need supplementation and issues that may require attention in applying the KMAP-DD 201227 to clinical practice.

METHODS

Treatment guidelines as comparison targets

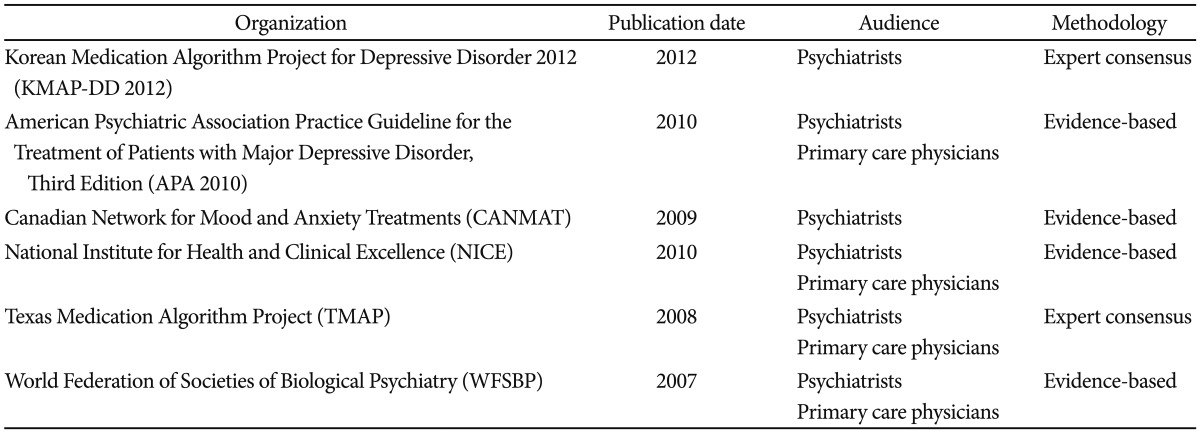

The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) developed an evidence-based treatment guideline to help clinicians with clinical decisions and published this guideline in 1993. The APA revised this guidelines into the Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, Second Edition. The second revision was published in 2010 and was named the Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition (APA 2010).19 Each treatment recommendation is categorized into one of three categories of endorsement depending on the level of clinical confidence (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of recently published treatment guidelines for depressive disorder

Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults

The Canadian Psychiatric Association and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments collaborated to publish evidence-based clinical guidelines for depression, which was first published in 2001.28 The guidelines were revised in 2009 to reflect new evidence.17 The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults (CANMAT)17 is an evidence-based treatment guideline based on a comprehensive literature review. The treatment recommendations are categorized into four criteria based on the level of evidence (Table 1).

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Guideline on the Treatment of Depression

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline for depression is one of the treatment guidelines published by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Experience. It is an evidence-based guideline based on a comprehensive literature review. The first edition of the NICE guideline for depression was published in 2004. The revision was published in 201020 (Table 1).

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project Procedural Manual: Major Depressive Disorder Algorithms

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP)21 is a guideline based on expert consensus developed by the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation and Texas University. The first edition was published in 1999, and the revision was published in 2008. Each treatment recommendation is categorized into three criteria, A, B, and C, depending on the level of evidence (Table 1).

World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Unipolar Depressive Disorders in Primary Care

The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guideline (WFSBP)18 is the treatment guideline for the pharmacotherapy of depression developed by the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry based on a comprehensive literature review. The first edition was published in 2002, and the revision was published in 2007 to reflect new evidence. Treatment recommendations are categorized into five criteria depending on the level of evidence (Table 1).

Development of the KMAP-DD

The KMAP-DD 201227 is an expert consensus guideline. For the second revision of the Korean Medication Algorithm for Depressive Disorder, the same framework as in the KMAP-DD 2006 (the first revision of the algorithm)23 was used. In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 the survey questionnaire included many of the main questions used in the KMAP-DD 200623 with several modifications. Questions regarding the treatment strategies for various subtypes of depression, depression with comorbid medical diseases, and non-pharmacologic biological treatment were newly added to the previous survey questionnaire. Finally, we developed a 44-item questionnaire comprised of six parts. The 9-point scale from the RAND Corporation29 was used to evaluate the adequacy of each treatment option. For review, the survey questionnaires were sent to 123 Korean psychiatrists. Among the 123 psychiatrists, 67 answered the survey. By estimating the mean and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of each question item, we classified each treatment opinion into one of three categories based on the lowest CI category: 6.5 or greater for first-line treatment, 3.5-6.5 for second-line treatment, and lower than 3.5 for third-line treatment. The first-line option that was rated by 50% or more of the experts was labeled as 'treatment of choice (TOC).' The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) from Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital, of which the IRB approval number was SC11QIMI0252.

RESULTS

Comparisons of recommendations across treatment guidelines

Initial treatment for depressive disorder

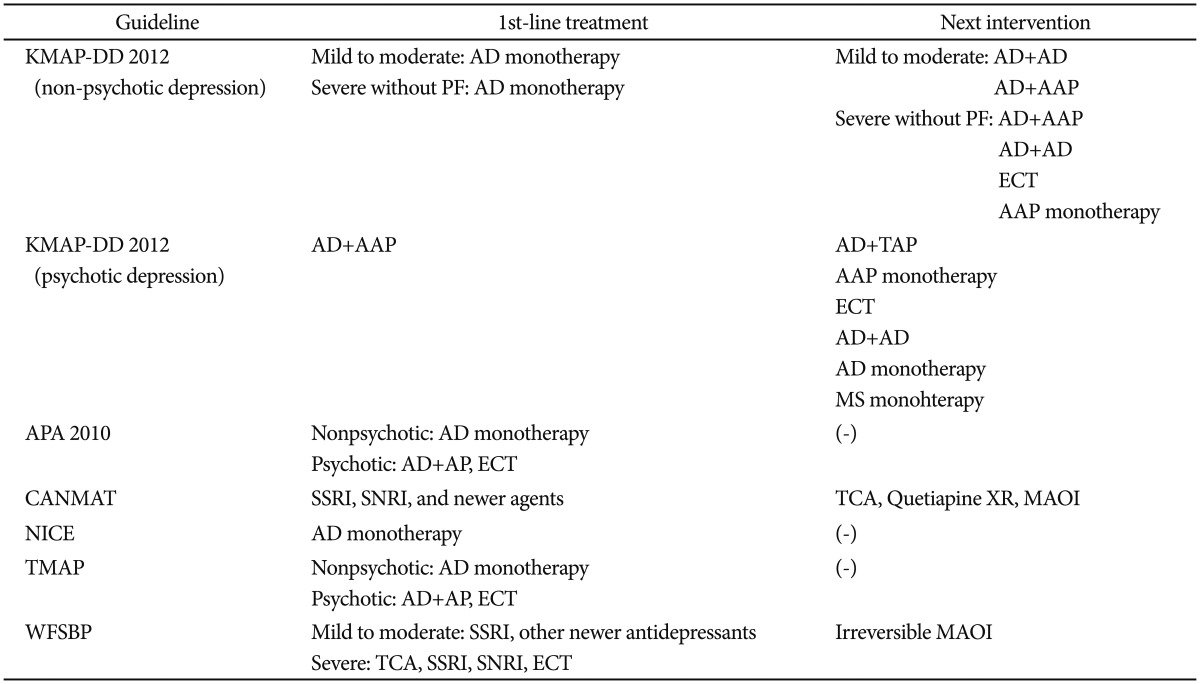

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 for nonpsychotic depression, antidepressant monotherapy is preferred as the first-line of treatment. For psychotic depression, the combination of an antidepressant and an atypical antipsychotic agent is preferred as the treatment of choice. Among antidepressants, for a mild to moderate episode, SSRIs excluding fluvoxamine, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) except milnacipran and mirtazpine are preferred antidepressants. For a severe episode, SSRIs excluding fluvoxamine and fluoxetine, SNRIs except milnacipran and mirtazpine are recommended. For a severe episode without psychotic features, mirtazpine, SSRIs except fluvoxamine, and SNRIs are preferred. Among antipsychotics, quetiapine, aripiprazole, olanzapine, and risperidone are preferred.

These recommendations are in line with the other treatment guidelines. In the APA 2010,19 WFSBP,18 and CANMAT,17 antidepressant monotherapy is recommend as the first-line of treatment for nonpsychotic depression, and the combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic agent is recommended for psychotic depression. Remarkably, in the CANMAT,17 quetiapine XR is suggested as an effective antidepressant based on numerous published studies on its efficacy in treating depression. However, due to its side effect profiles and lack of data comparing its efficacy with SSRIs, it is recommended as second-line treatment. The NICE20 guideline also recommends SSRIs because of their favorable side effect profiles compared to other antidepressants. The TMAP21 recommends the treatment strategies based on stages by dividing depression into two categories (psychotic depression vs. nonpsychotic depression). Broadly speaking, the recommendations for initial treatment in the TMAP21 are similar to those of the KMAP-DD 201227 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Initial strategies for pharmacological treatment in major depressive disorder across practice guidelines

AD: antidepressant, AAP: atypical antipsychotic agent, ECT: Electroconvulsive therapy, TAP: typical antipsychotic agent, MS: mood stabilizer, PF: psychotic features, SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, AP: antipsychotic agent, TCA: tricyclic antidepressant, Quetiapine XR: extended release formulation of quetiapine, MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor, KMAP-DD: Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder, APA: American Psychiatric Association, CANMAT: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, TMAP: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, WFSBP: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

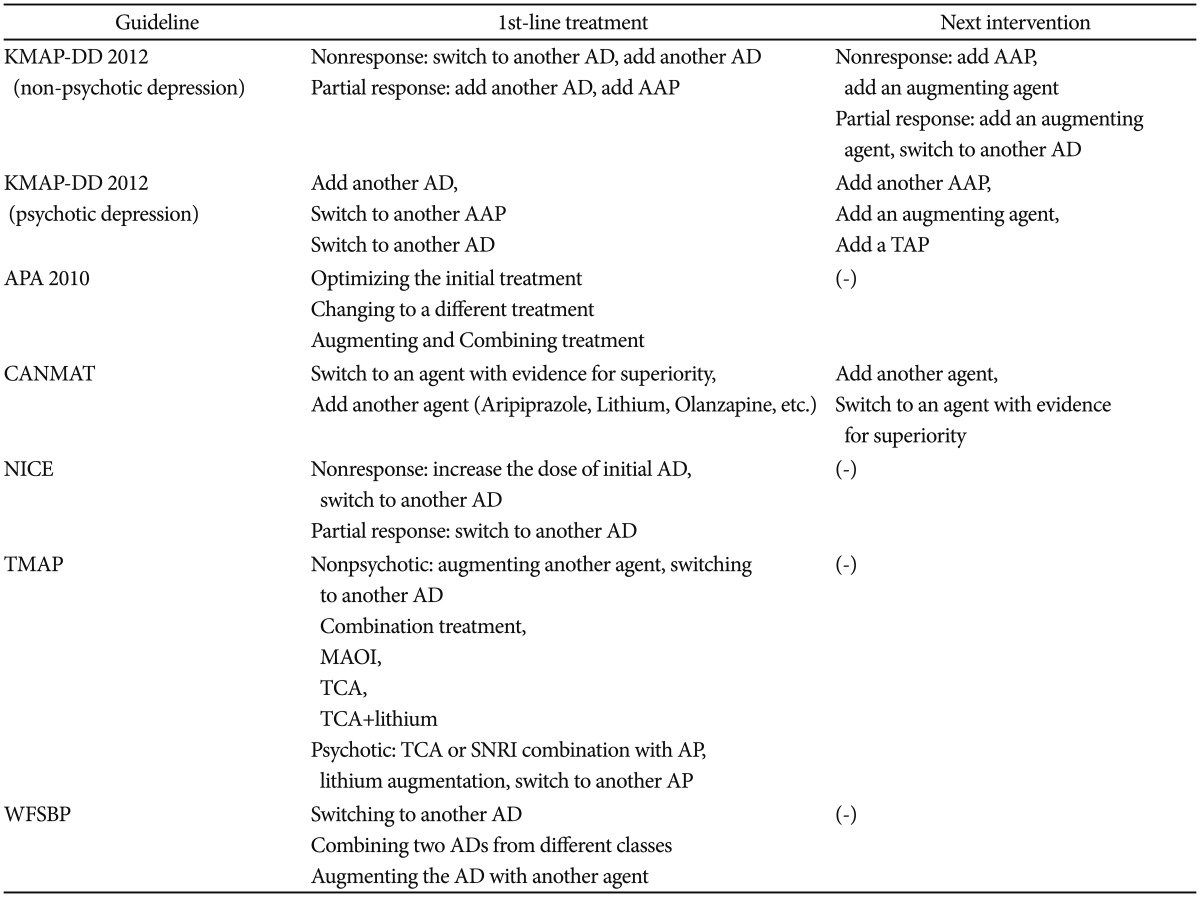

Second step treatment in cases of nonresponse or incomplete response to initial treatment

In the case of nonresponse for nonpsychotic depression, the KMAP-DD 201227 recommends switching to or adding another antidepressant. In the case of incomplete response in nonpsychotic depression, the addition of another antidepressant or an atypical antipsychotic agent is recommended. Among antipsychotics, aripiprazole and quetiapine are preferred. Among augmenting agents, lithium and anticonvulsants are preferred. For psychotic depression, supplemental antidepressant, switching to another antidepressant, or switching to another atypical antipsychotic agent are preferred first options (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment strategies for partial response or non-response to initial treatment in major depressive disorder across practice guidelines

AD: antidepressant, AAP: atypical antipsychotic agent, TAP: typical antipsychotic agent, MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor, TCA: tricyclic antidepressant, SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, AP: antipsychotic agent, KMAP-DD: Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder, APA: American Psychiatric Association, CANMAT: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, TMAP: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, WFSBP: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

The APA 201019 recommends increasing the medication dose, adding an augmenting agent, or switching to another antidepressant when initial treatment fails to result in complete response. It also recommends that lithium, thyroid hormone, or the addition of an atypical antipsychotic agent be considered as second-line strategies. In the CANMAT,17 switching to another antidepressant and adding augmenting agents such as aripiprazole, lithium, olanzapine, risperidone are recommended as first-line treatment. This recommendation highlights that aripiprazole, olanzapine, and lithium are recommended with Level 1 evidence among the various augmenting agents. In the TMAP,21 switching to another antidepressant in a different class is preferred. Additionally, the TMAP21 recommends that, even when the switch to another antidepressant fails to show complete response, mirtazpine, bupropion, lithium, T3, and buspirone can be considered as an augmenting agent in the next step. In the WFSBP,18 switching to another antidepressant, combining two antidepressants from different classes, and adding another augmenting agent are recommended as second step treatment. The WFSBP18 does not describe which strategy is superior in efficacy and safety, while it provides information about the pros and cons of each treatment strategy based on evidence (Table 3).

Third step treatment in cases of nonresponse or incomplete response to second step treatment

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 third step treatment strategies were surveyed in each clinical situation. The KMAP-DD 201227 recommends switching to or adding another antidepressant, switching to or adding another atypical antipsychotic agent, or adding an augmenting agent that were not previously tried in the first and the second step treatment. However, the other treatment guidelines reviewed here except for the TMAP21 do not separate second and third steps of treatment. They only provide recommendations in the cases of nonresponse or incomplete response to initial treatment. Only the TMAP21 provided treatment recommendations for each stage. The TMAP21 recommends that lamotrigine, MAOI, and D2 agonist can be considered as an augmenting agent in this step.

Maintenance therapy for psychotic depression

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 when a patient experiences remission after the combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic agent, it was the opinion of the majority of clinicians to maintain the antidepressant used during the acute phase for at least 19.4 weeks to a maximum of 43.2 weeks for the first episode of depression. For the second episode of depression, it was the opinion of the majority of clinicians to maintain for at least 41.9 weeks to a maximum of 82.3 weeks. For more than three episodes of depression, it was the major opinion of clinicians to maintain the antidepressant for an indefinite period of time. Additionally, the dose of the antidepressant during maintenance therapy was 75% of that used during the acute phase. In terms of antipsychotic agents, for the first episode of depression, it was the opinion of the majority of clinicians to maintain the antipsychotic agent used during the acute phase for at least 15.0 weeks to a maximum of 33.5 weeks. For the second episode, it was for at least 25.7 weeks to a maximum of 58.3 weeks. From the third episode and onward, it was the opinion of the majority of clinicians that the antipsychotic agent should be maintained for an indefinite period of time. The dose of the antipsychotic agent during maintenance therapy was 50% of that used during the acute phase.

In the WFSBP,18 it is recommended that clinicians maintain the medication (e.g., antidepressants or antipsychotics) when risk factors for recurrence exist. It also recommends that maintenance therapy should persist for at least 3 years based on existing evidence. The NICE20 recommends that clinicians should continue maintenance therapy for at least 2 years when there are risk factors for recurrence, and that the dosage of each medication should be the same as that during the acute phase of treatment. In the CANMAT,17 it is recommended that the maintenance therapy be continued for at least 6 months to 5 years based on the results of a meta-analysis.30 The dosages of medication during the maintenance are recommended to be the same as those during the acute phase treatment.30 The APA 201019 recommends that maintenance therapy should last for at least 4 to 9 months, during which the dosages of medication be the same as those during the acute phase. However, in the case of recurrent depression with more than 3 episodes, chronic depression, and high-risk patients, maintenance therapy is recommended to persist for an indefinite period of time. In the TMAP,21 treatment recommendations for maintenance therapy differ between psychotic depression and nonpsychotic depression. For nonpsychotic depression, maintenance therapy with the same dosage used during the acute phase should be continued for at least 6 to 9 months. After that, maintenance therapy should be individualized depending on the risks of recurrence of each patient. For psychotic depression, it is recommended that the antidepressant be continued for an indefinite period of time, and that the antipsychotic agent be continued for at least 4 months.

Pharmacologic treatment for dysthymic disorder and each depression subtype

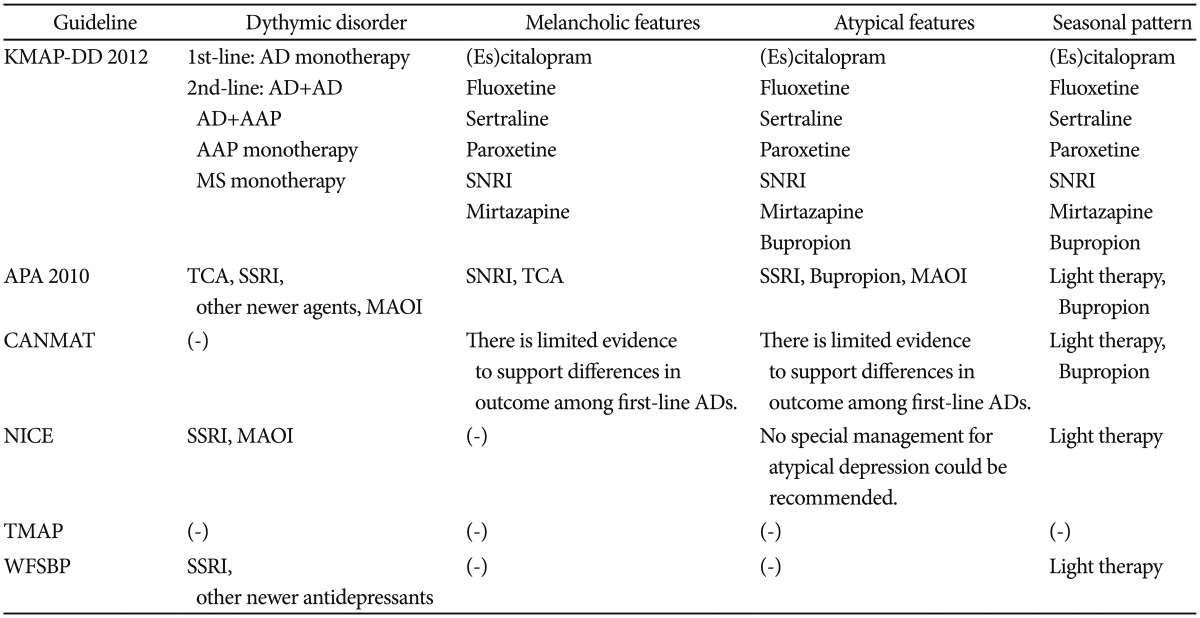

Pharmacologic treatment for dysthymic disorder

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 antidepressant monotherapy is preferred as the treatment of choice. Among the medications, SSRIs except fluvoxamine, SNRIs, and mirtazapine are preferred as the first-line of treatment. These findings are similar to those in other treatment guidelines. In the APA 2010,19 NICE,20 and WFSBP,18 antidepressant monotherapy is recommended as first-line treatment despite limited evidence (Table 4).

Table 4.

Treatment for each subtype of depressive disorder across practice guidelines

AD: antidepressant, AAP: atypical antipsychotic agent, MS: mood stabilizer, SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, TCA: tricyclic antidepressant, SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitor, ECT: Electroconvulsive therapy, KMAP-DD: Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder, APA: American Psychiatric Association, CANMAT: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, TMAP: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, WFSBP: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

Pharmacologic treatment for melancholic features

In the KMAP-DD 2012, (es)citalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, SNRIs, and mirtazapine are preferred as first-line antidepressants. There are some differences in treatment recommendations across the treatment guidelines reviewed here. The APA 201019 mentions that TCAs and SNRIs may be more effective than SSRIs. However, the CANMAT17 reported that there is no significant difference in efficacy among first-line antidepressants.

Pharmacologic treatment for atypical features

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 (es)citalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, SNRIs, mirtazapine, and bupropion are preferred as first-line antidepressants. The APA 201019 reports that MAOIs are superior in efficacy to TCAs. However, the NICE20 reports that the evidence for each treatment option in atypical features is limited. Further, the CANMAT17 reports that there is no significant difference in efficacy among first-line antidepressants.

Pharmacologic treatment for depression with seasonal pattern

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 (es)citalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, SNRIs, mirtazapine, and bupropion are preferred as first-line antidepressants. The APA 201019 does not suggest a specific pharmacologic strategy; however, it recommends adjunctive light therapy for depression with a seasonal pattern. The APA 201019 also mentions that the extended release formulation of bupropion is approved by the FDA for major depression with a seasonal pattern. In the CANMAT,17 Level 1 evidence shows that bupropion is recommended for the prevention of depressive episodes in the winter. The NICE20 also mentions the efficacy of light therapy; however, it reports that the evidence for each treatment option for depression with seasonal pattern is insufficient. In the WFSBP,18 light therapy is recommended for seasonal pattern depression with Level A evidence.

Pharmacologic treatment for minor depressive disorder

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 the major opinion of Korean experts for minor depressive disorder is pharmacologic treatment. The majority (77%) of Korean experts who answered the survey questionnaires indicated that the duration of maintenance therapy for minor depressive disorder could be shorter than that for major depressive disorder. These findings differ from the recommendations of other treatment guidelines. The NICE20 reports that the use of antidepressants is not routinely recommended for subthreshold depressive symptoms or minor depression. In the WFSBP,18 it is mentioned that the benefit of antidepressant use is uncertain in these cases.

Special populations

Pharmacologic treatment of child and adolescent depression

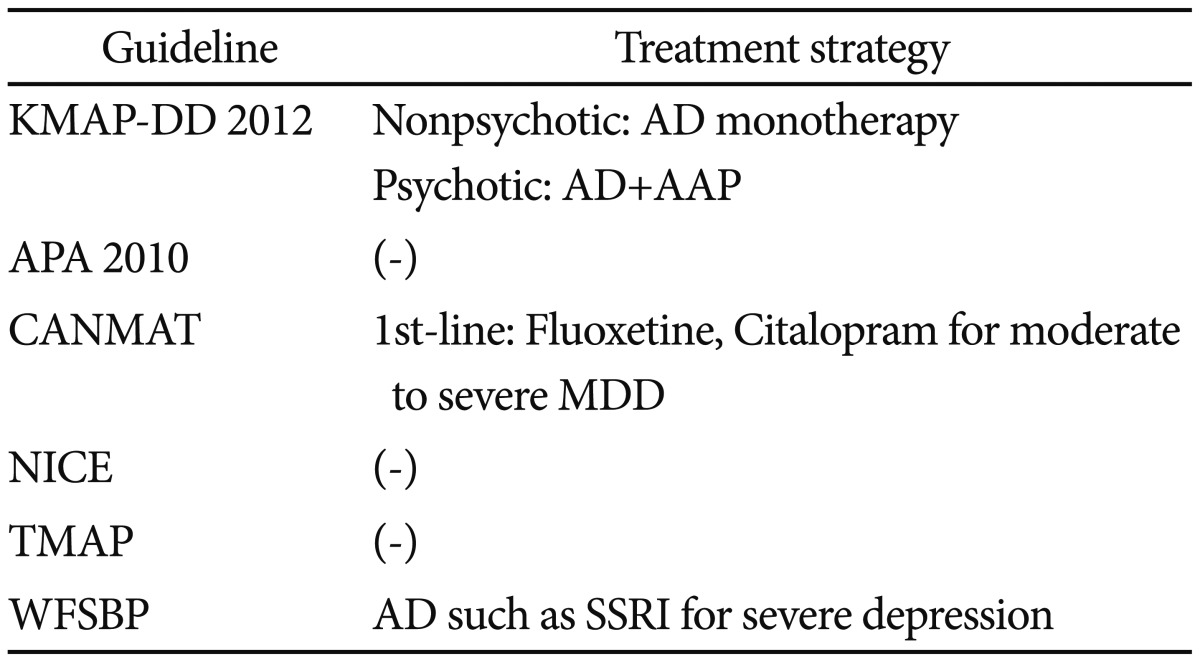

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 antidepressant monotherapy is preferred as the primary treatment for nonpsychotic depression. For psychotic depression, the combination of an antidepressant and an atypical antipsychotic agent is preferred as the treatment of choice. The CANMAT17 reports that pharmacotherapy for depression in children and adolescents is a topic of controversy because of the risks involved, including increased suicidality and limited evidence of efficacy. Thus, the CANMAT17 recommends that the use of antidepressants should be carefully considered for moderate to severe depression after weighing its benefits and risks. Among antidepressants, fluoxetine and citalopram are recommended as first-line antidepressants with Level 1 evidence. The recommendations of the WFSBP18 are similar to those of the CANMAT.17 The WFSBP18 recommends that antidepressants should be considered with caution for severe depression or psychotic depression because there is risk of increased suicidality in children and adolescents. SSRIs are recommended as first-line antidepressants with Level B evidence (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pharmacological treatment for major depressive disorder in child and adolescent across practice guidelines

AD: antidepressant, AAP: atypical antipsychotic agent, MDD: major depressive disorder, SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, KMAP-DD: Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder, APA: American Psychiatric Association, CANMAT: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, TMAP: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, WFSBP: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

Pharmacologic treatment of geriatric depression

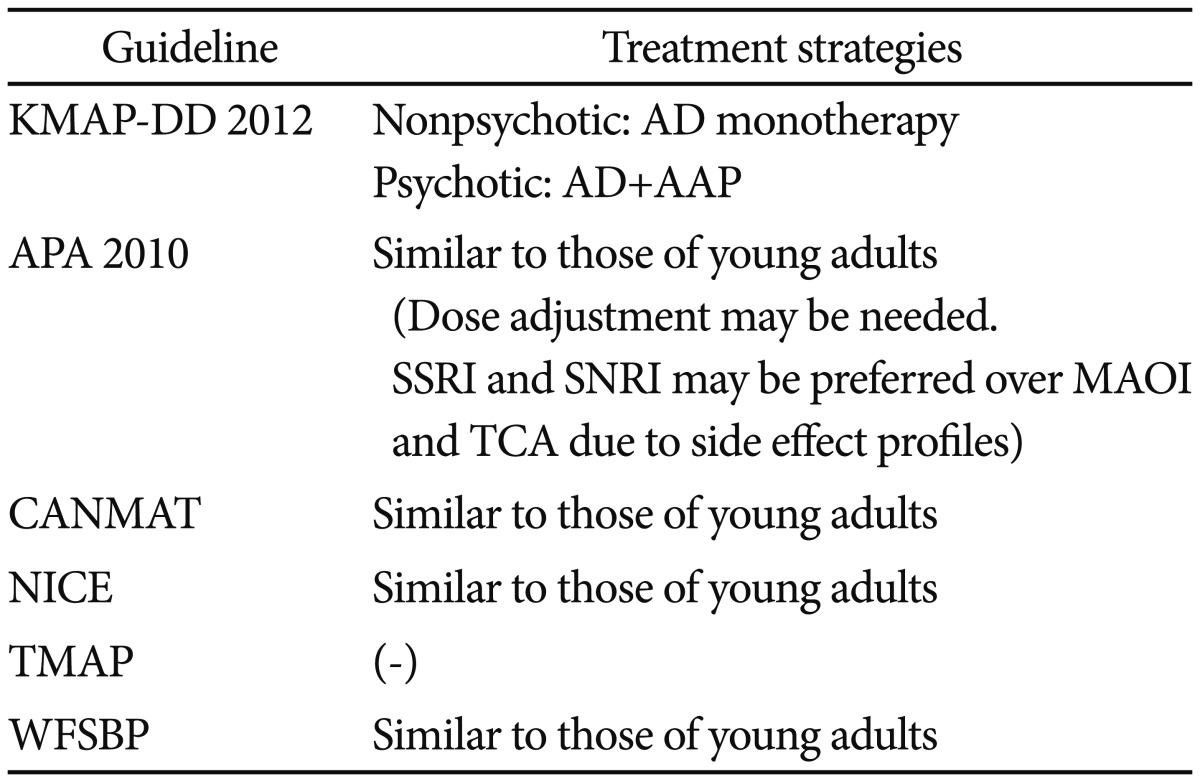

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 antidepressant monotherapy is recommended as the primary treatment for mild to moderate episodes in the elderly. For severe episodes without psychotic features, antidepressant monotherapy is preferred. For psychotic depression, the combination of an antidepressant and an atypical antipsychotic agent is preferred. Additionally, for nonpsychotic depression in the elderly, SSRIs except fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, SNRIs, and mirtazapine are recommended as first-line antidepressants. For psychotic depression, SSRIs except fluvoxamine, SNRIs, and mirtazpine are preferred.

These recommendations are similar to those in other treatment guidelines. The APA 201019 recommends that, because of the vulnerability of the elderly to anticholinergic side effects and orthostatic hypotension, SSRIs and SNRIs are preferred rather than MAOIs and TCAs. The NICE20 suggests that overall pharmacologic treatment recommendations for the elderly do not significantly differ from those of adults, and that clinicians should pay attention to the occurrence of side effects in this age group. The WFSBP18 recommends that clinicians should pay attention to comorbid medical diseases and the physiologic changes that can influence drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics common in this age group. In the WFSBP,18 SSRIs such as sertraline, paroxetine, and fluoxetine are preferred with Level A evidence (Table 6).

Table 6.

Pharmacological treatment for major depressive disorder in the elderly across practice guidelines

AD: antidepressant, AAP: atypical antipsychotic agent, SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, MAOI: monoamine oxidase inhibitors, TCA: tricyclic antidepressants, KMAP-DD: Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder, APA: American Psychiatric Association, CANMAT: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, TMAP: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, WFSBP: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

Pharmacologic treatment for postpartum depression

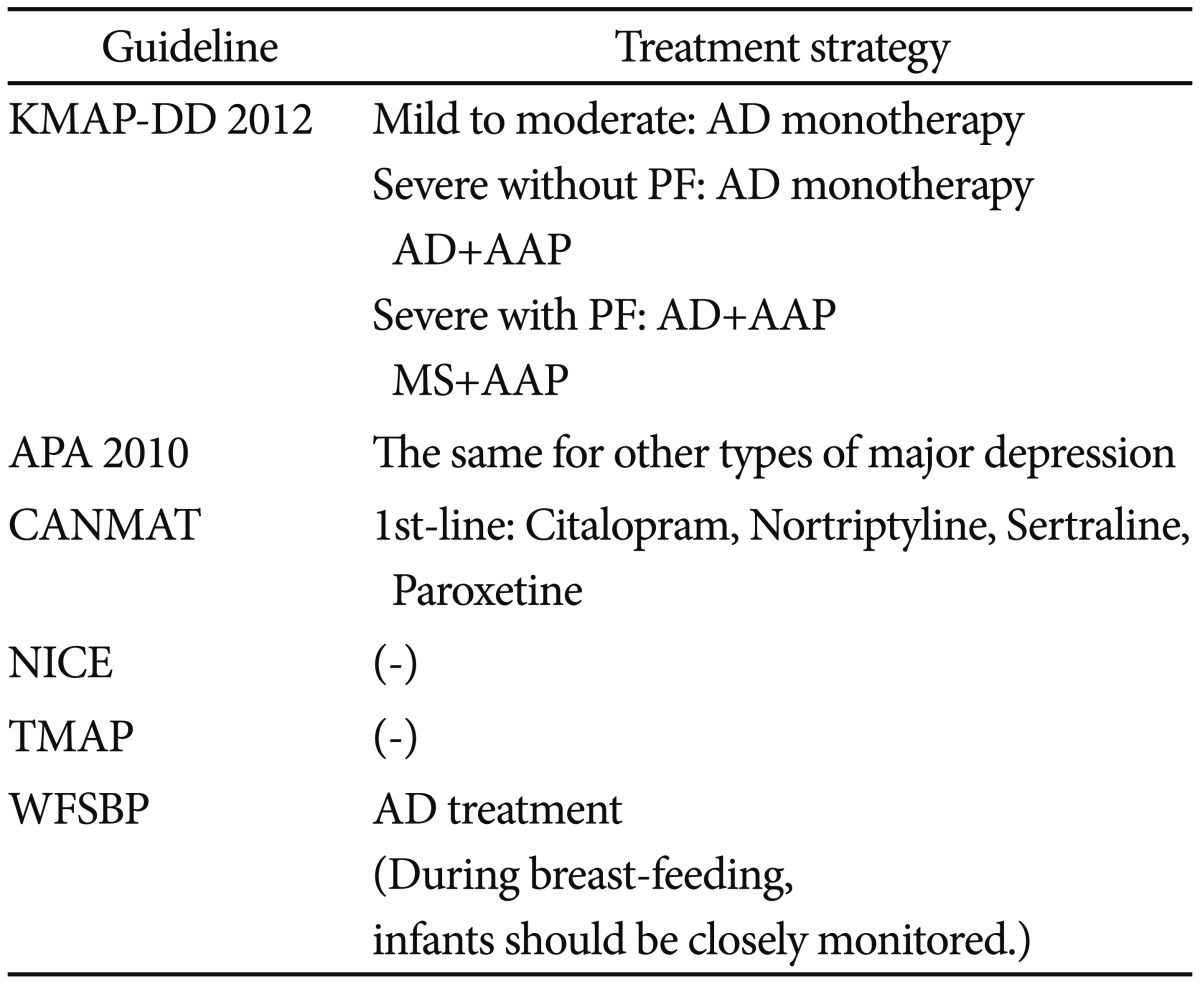

For postpartum depression, the KMAP-DD 201227 recommends antidepressant monotherapy for mild to moderate episodes. For severe episodes without psychotic features, both antidepressant monotherapy and the combination of an antidepressant and an atypical antipsychotic agent are preferred as first-line treatment. For psychotic depression, the combination of an antidepressant and an atypical antipsychotic agent and the combination of a mood stabilizer and an atypical antipsychotic agent are preferred. The CANMAT17 recommends citalopram, nortriptyline, setraline, and paroxetine as first-line antidepressants with Level 3 evidence. However, the CANMAT17 does not describe the use of mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotics. In the APA 2010,19 the same pharmacologic treatment for all adults with major depressive disorder is recommended (Table 7).

Table 7.

Pharmacological treatment for postpartum depression

AD: antidepressant, AAP: atypical antipsychotic agent, MS: mood stabilizer, KMAP-DD: Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder, APA: American Psychiatric Association, CANMAT: Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, TMAP: Texas Medication Algorithm Project, WFSBP: World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry

Choosing antidepressants in specific situations

The choice of antidepressant according to adverse events

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 bupropion is preferred as a primary antidepressant and mirtazpine as a secondary antidepressant when there is a concern of sexual dysfunction. When weight gain is a concern, bupropion, fluoxetine and (es)citalopram are preferred. When sleep disturbances are comorbid with depression, mirtazapine is preferred. For the concern of anticholinergic side effects, (es)citalopram is recommended. These findings are in line with other treatment guidelines. The APA 201019 recommends that clinicians consider lowering the dose of the antidepressant or switching to another antidepressant with a lower risk of the related side effects when some side effects occur during pharmacotherapy. The APA 201019 also mentions that SSRIs and SNRIs are not appropriate for patients who suffer from sexual dysfunction. For overweight/obesity concerns, the APA 201019 also recommends that clinicians should regularly monitor the weight change and should consider diet, exercise, switching to another agent, and nutritional counseling if needed. The CANMAT17 reports sexual dysfunction related to the use of SSRIs and SNRIs and mentions that fluoxetine and paroxetine have relatively higher risk for sexual dysfunction and (es)citalopram a relatively lower risk among SSRIs. The CANMAT17 also mentions that bupropion, mirtazapine, and moclobemide do not have a higher risk for sexual dysfunction than placebo. The TMAP21 suggests that a selective phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor be considered if needed for sexual dysfunction.

The choice of antidepressant according to safety issues

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 (es)citalopram is considered the antidepressant with the lowest risk of hypertension, seizure, and arrhythmia. In the APA 2010,19 it is recommended that clinicians should closely monitor EKG and vital signs during treatment in patients with hypertension and cardiovascular disease. The APA 201019 also recommends regular EKG monitoring during the use of TCAs and the regular monitoring of vital signs such as pulse and blood pressure during the use of SNRIs. Further, it states that SSRIs can be used safely in the presence of cardiovascular diseases. Additionally, the APA 2010 suggests that bupropion and clomipramine be used with caution in the presence of seizure because these agents can lower the seizure threshold. The CANMAT17 also mentions that TCAs have a higher risk of seizure compared to SSRIs. It mentions that, if clinicians use bupropion within the recommended dose range, the risk for seizure does not increase because the risk is dose-dependent. The NICE20 mentions that high doses of venlafaxine can exacerbate cardiac arrhythmia; thus, the blood pressure of patients with hypertension should be regularly monitored when using venlafaxine.

The choice of antidepressant according to comorbid physical illnesses

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 in the case of comorbid physical illnesses such as diabetes, liver disease, or renal disease, (es) citalopram is the preferred antidepressant, while sertraline is the second-line antidepressant. The APA 201019 mentions that TCAs can negatively influence control of blood sugar level; thus, SSRIs are preferred for diabetic patients.

Non-pharmacologic biological therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is recommended as the first-line treatment for severe depression with acute suicide risk, regardless of the presence of psychotic features. For nonpsychotic severe depression, ECT is considered for second-line treatment when two antidepressants fail to show complete response. For psychotic depression, ECT is considered for second-line treatment when patients fail to respond to the combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic agent. Additionally, ECT is considered for second-line treatment for both moderate episodes resistant to pharmacotherapy and severe episodes in pregnant women. ECT is not the first-line treatment in general psychiatric practice for depression. However, it is preferred under specific situations such as the presence of acute suicide risk. As compared to the recommendations in the KMAP-DD 2006 in which ECT was recommended as the first-line of treatment for severe episodes resistant to the combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic agent and moderate episodes resistant to pharmacotherapy, the KMAP-DD 2012 reflects the decreased preference for ECT in clinical practice. However, in most treatment guidelines reviewed here including the APA 2010,19 WFSBP,18 TMAP,21 and CANMAT,17 ECT is still the preferred first-line treatment for psychotic depression.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is not recommended as a first-line of treatment for depression; however, it is considered secondary treatment for severe episodes that fail to show response to two adequate antidepressant trials and moderate episodes resistant to pharmacotherapy. The CANMAT17 mentions that rTMS can be considered in patients who have failed to respond to at least one antidepressant trial. The APA 201019 mentions that rTMS is approved for patients who fail to respond to at least one antidepressant trial, even though the evidence for its efficacy is still insufficient. The NICE20 also notes that the evidence of rTMS efficacy in treating depression is limited, and further studies to investigate its efficacy and safety are needed.

Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for treatment-resistant depression

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 complementary and alternative medicine treatment such as vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS) were not recommended as first-line treatment. However, light therapy and nutritional therapy (including Omega-3 and megavitamine) were noted as second-line treatments. The APA 201019 mentions that VNS can be considered for treatment-resistant depression; however, the evidence of its efficacy during the acute phase is insufficient. The CANMAT17 also notes that evidence of the efficacy of VNS in treating depression in its acute phase is limited. The TMAP21 recommends that VNS be considered as an adjunctive therapy to the antidepressant trial in cases of incomplete response at Stage 5. The CANMAT17 mentions that the studies that demonstrated the efficacy of DBS are increasing; however, the evidence of its use in depression is still insufficient.

DISCUSSION

In this review, we compared the recommendations of the KMAP-DD 201227 with those of other widely used treatment guidelines. First, for the initial treatment, there were no significant differences across treatment guidelines. For secondary strategies for nonresponse or incomplete response to the initial treatment, there were some differences among the treatment guidelines. The TMAP21 and WFSBP18 recommend conventional treatment options such as the combination of two antidepressants and the addition of another augmenting agent, while the KMAP-DD 2012, APA 2010,19 and CANMAT17 recommend the addition of an atypical antipsychotic agent. These results are thought to reflect the recent medical situation in Korea in which the preference of Korean clinicians for atypical antipsychotics has increased because of accumulated evidence of their efficacy in treating depressive symptoms.24-26

For maintenance therapy of psychotic depression, the KMAP-DD 2012 revealed the prescription pattern of a relatively shorter duration of maintenance therapy and a lower dosage of medication by Korean psychiatrists compared to the recommendations of other treatment guidelines. Generally, other treatment guidelines recommend the same dosage to be used during the maintenance phase as that used during the acute phase. These differences between the KMAP-DD 2012 and other guidelines should be interpreted with caution by considering several aspects. In previous studies, factors such as the prejudice or beliefs of patients' family about depression and its treatment, social support, race, and cultural background can influence treatment compliance.31 However, there have been very few studies that have investigated whether there were differences in treatment compliance between Korea and other countries or whether there were factors that could explain such differences.31,32 The Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service reported that antidepressant adherence rate among Korean patients with depression was lower than that in other countries based on the analysis of Korean health insurance data.32 Lee et al.31 reported that premature treatment discontinuation rate was 43.5% at 6 weeks among outpatients with major depression who were prescribed a single antidepressant across four university hospitals in Korea. Based on these results, it appears that poor treatment compliance among patients with depression is one of the major issues impacting Korean clinicians. It is likely that clinician concern of poor treatment compliance in Korea might influence their treatment patterns (e.g., relatively shorter duration of maintenance therapy and lower dosages of medication during maintenance therapy) in the KMAP-DD 2012 compared to other treatment guidelines. As such, more systematized, large-scale studies that investigate treatment compliance and the factors influencing compliance in Korea are much needed. Thus, based on those study results, the treatment recommendations for maintenance therapy should be supplemented and modified for domestic circumstances in Korea.

In the KMAP-DD 2012,27 SSRIs, SNRIs and mirtazpine are preferred as first-line treatments for melancholic and atypical features. The APA 201019 reported that TCAs and SNRIs are preferred to SSRIs for melancholic features, and that MAOIs are more efficacious than TCAs for atypical features. However, the CANMAT17 notes that there are no significant differences in treatment efficacy among antidepressants. As such, there was no agreement regarding the treatment options according to depression subtype across the treatment guidelines. For a seasonal pattern of depression, the APA 2010,19 CANMAT,17 and WFSBP18 noted the efficacy of light therapy; however, in the KMAP-DD 2012, light therapy is only considered as secondary treatment in cases of incomplete response to initial treatment. This difference may reflect the lower preference for light therapy in Korean clinicians. Studies investigating the efficacy of light therapy for depression with seasonal pattern are very rare in Korea, including only a single case report.33 The lack of clinical experience may result in a lower preference for light therapy among Korean clinicians.

The treatment recommendations for special populations are new in the KMAP-DD 2012 compared to KMAP-DD 2006. For depression among children and adolescents, there were no significant differences in recommendations between KMAP-DD 201227 and other guidelines. However, other guidelines including those of the CANMAT17 and WFSBP18 noted the potential risks of antidepressant usage in this age group. Thus, they recommended antidepressant use only for moderate to severe depressive episodes. For depression among the elderly, there were no significant differences in treatment recommendations between the KMAP-DD 201227 and other treatment guidelines. For postpartum depression, the recommendations of the KMAP-DD 201227 showed a higher preference of Korean clinicians for the use of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics for severe depressive symptoms compared to the APA 201019 and CANMAT.17

Among various non-pharmacologic biological treatments, the use of ECT was most often described. Generally, the preference for ECT in the KMAP-DD 201227 was lower than other treatment guidelines.

KMAP-DD 201227 has limitations as an expert consensus guideline. Thus, we made efforts to compensate these limitations by holding the public hearing at the Academic Conference of Korean College of Neuropsychopharmacology, and by opening the result announcement and panel discussion at the Academic Conference of Korean Society for Depressive and Bipolar Disorders. Despite the limits of expert opinion, this comparison showed that there were no major differences in overall treatment recommendations between the KMAP-DD 201227 and other guidelines. Further, the recommendations of the KMAP-DD 201227 are thought to reflect current changes in pharmacotherapy of depression based on newer evidence. However, we also found some differences between the KMAP-DD 201227 and other guidelines for the recommended secondary steps of treatment, maintenance therapy, and the treatment of some depression subtypes. We think that this is likely due to the few number of studies in these areas and as studies on these issues increase, the modification of related recommendations should be considered. Finally, we believe that the KMAP-DD 201227 will provide useful information to Korean clinicians in their clinical decision-making and that it is well administered in Korean clinical practice.

References

- 1.Keller MB, Roland RJ. Implications of failing to achieve successful long-term maintenance treatment of recurrent unipolar major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:348–360. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg D. The "NICE Guideline" on the treatment of depression. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Spencer D, Fava M. The STAR*D study: treating depression in the real world. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:57–66. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.75.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathys M, Mitchell BG. Targeting treatment-resistant depression. J Pharm Pract. 2011;24:520–533. doi: 10.1177/0897190011426972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viner MW, Chen Y, Bakshi I, Kamper P. Low-dose risperidone augmentation of antidepressants in nonpsychotic depressive disorders with suicidal ideation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:104–106. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200302000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunner DL, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Loebel A, Romano SJ. Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive ziprasidone in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, open-label, pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1071–1077. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papakostas GI, Petersen TJ, Kinrys G, Burns AM, Worthington JJ, Alpert JE, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1326–1330. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adson DE, Kushner MG, Eiben KM, Schulz SC. Preliminary experience with adjunctive quetiapine in patients receiving selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19:121–126. doi: 10.1002/da.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbee JG, Conrad EJ, Jamhour NJ. The effectiveness of olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone as augmentation agents in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:975–981. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meltzer-Brody S. New insights into perinatal depression: pathogenesis and treatment during pregnancy and postpartum. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:89–100. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/smbrody. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yonkers KA, Vigod S, Ross LE. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of mood disorders in pregnant and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:961–977. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821187a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birmaher B, Brent D, Bernet W, Bukstein O, Walter H, et al. AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes CW, Emslie GJ, Crismon ML, Posner K, Birmaher B, Ryan N, et al. Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project: update from Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Major Depressive Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:667–686. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31804a859b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor WD, Doraiswamy PM. A systematic review of antidepressant placebo-controlled trials for geriatric depression: limitations of current data and directions for the future. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:2285–2299. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunner DL. Treatment considerations for depression in the elderly. CNS Spectr. 2003;8(12 Suppl 3):14–19. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900008233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Parikh SV, Patten SB, Ravindran AV. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. Introduction. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauer M, Bschor T, Pfennig A, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Versiani M, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for Biological Treatment of Unipolar Depressive Disorders in Primary Care. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;8:67–104. doi: 10.1080/15622970701227829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Treatment of Patients with Major Depression and Practical Guideline. 3rd Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (commissioned by the National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence) Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults. (updated edition) London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suehs B, Argo TR, Bendele SD, Crimson ML, Trivedi MH, Kurian B. Texas Medication Algorithm Project Procedural Manual Major depressive disorder algorithms. Texas: Texas Department of State health Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn YM, Kim DJ, Kwon JS, Bahk WM, Lee HS, Kim YS. Korean Medication Algorithm Projects for Major Psychiatric Disorders(I) : The Genefit and Risk of Algorithm and the General Considerations of Developing Medication Algorithm. Korean J Psychopharmacol. 2002;13:18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seo JS, Min KJ, Kim W, Seok JH, Bahk WM, Song HC, et al. Korean Medication Algorithm for Depressive Disorder 2006 (I) J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2007;46:453–460. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nemeroff CB. Use of atypical antipsychotics in refractory depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 8):13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Smith J, Fava M. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotic medications for treatment-resistant major dperessive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:826–831. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papakostas GI, Petersen TJ, Kinrys G, Burns AM, Worthington JJ, Alpet JE, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treamtent-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1326–1330. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Executive Committee of Korean Medication Algorithm Project for Depressive Disorder 2012. Korean Medication Guideline for Depressive Disorder 2012. Seoul: ML communication; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Canadian Psychiatric Association; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(Suppl 1):5S–90S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sachs GS, PRintz DJ, Kahn DA, Carpenter D, Docherty JP. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000. Postgrad Med. 2000;Spec No:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam RW, Kenney SH, Grigoriadis S, McIntyre RS, Milev R, Ramasubbu R, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III. Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S26–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee KU, Kim W, Min KJ, Shin YC, Chung SK, Bahk WM. The Rate and Risk Factors of Early Discontinuation of Antidepressant Treatment in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Korean J Psychopharmacol. 2006;17:550–556. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim NS, Kim KH, Lee SM, Paik JW, Lee BR, Hwang JH. Health Services Utilization and Depression Care Quality among Depressed Patients. Seoul: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joe SH, Lee HJ. A case of morning light treatment for a depressive episode with seasonal pattern. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1998;37:585–592. [Google Scholar]