Abstract

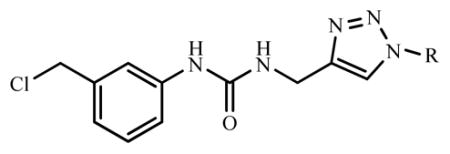

Novel lead was developed as VEGFR-2 inhibitor by the back-to-front approach. Docking experiment guided that the 3-chloromethylphenylurea motif occupied the back pocket of the VEGFR-2 kinase. The attempt to enhance the binding affinity of 1 was made by expanding structure to access the front pocket using triazole as linker. A library of 1,4-(disubsituted)-1H-1,2,3-triazoles were screened in silico and one lead compound (VH02) was identified with enzymatic IC50 against VEGFR-2 of 0.56 μM. VH02 showed antiangiogenic effect by inhibiting the tube formation of HUVEC cells (EA.hy926) at 0.3 μM which was 13 times lower than its cytotoxic dose. The enzymatic and cellular activities suggested the potential of VH02 as a lead for further optimization.

Keywords: VEGFR-2; VEGFR-2 inhibitor; molecular modeling; antiangiogenesis; 1,4-disubstituted 1; 2,3-triazoles; CuAAC reaction

Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) is a class of protein tyrosine kinase that regulate inter- and intracellular communications by signal transduction. These proteins have a major role in regulation of cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, survival and metabolism3, 4. Among RTK, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) is a main target in suppressing cancer growth and metastasis due to its vital role in angiogenesis regulation5–8.

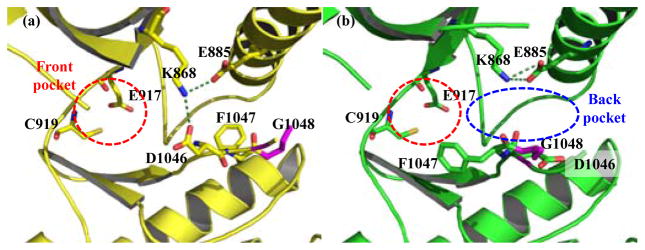

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be classified into two main types according to its binding pose. Type I inhibitors bind specifically to the adenine-binding or ATP site of kinase in the active form of enzyme and type II inhibitors bind to the ATP site and additional hydrophobic back pocket, the allosteric site, found in the inactive form of kinase. Different conformation between the active and inactive states of tyrosine kinases are observed at the beginning of the activation loop which composed of highly conserved triad Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG). In the active state, kinase adopts DFG-in conformation whereas the conformation of the inactive state adopts DFG-out conformation (Figure 1). Type II kinase inhibitors were found to be more selective than type I inhibitors in drug development9–14. Thus, the binding site, normally used as a target in structure-based drug design for small molecule kinase inhibitors, composes of a front or ATP-binding pocket and a hydrophobic back pocket forming by the DFG-out conformation15. In the front pocket, two key amino acid residues participating in H-bond interaction with the adenine ring of ATP are Glu917 and Cys919 which locate in the hinge area of the binding site. Two key amino acids in the back pocket participating in H-bond interaction are Glu885 locating in αC-helix and Asp1046, a part of DFG-motif in the activation loop. Most of VEGFR-2 inhibitors apparently form hydrogen bonding interaction with these key amino acid residues16–18.

Figure 1.

Binding site in VEGFR-2 kinase domain with key residues participating in H-bond forming (a) DFG-in conformation (PDB code: 3B8R)2 showing ATP-binding site in red circle and two salt bridges from Lys868 in green dotted line; (b) DFG-out conformation (PDB code: 3EWH)1, allosteric pocket in blue circle located in the back ATP site.

Back-to-front approach, the design of type II kinase inhibitors starting from the back-pocket binding group and expanding the core structure toward the front pocket, is one strategy used in kinase drug development. This approach was successful in lead finding of p38α kinase inhibitors19 cFMS kinase inhibitors20 and VEGFR-2 inhibitors21.

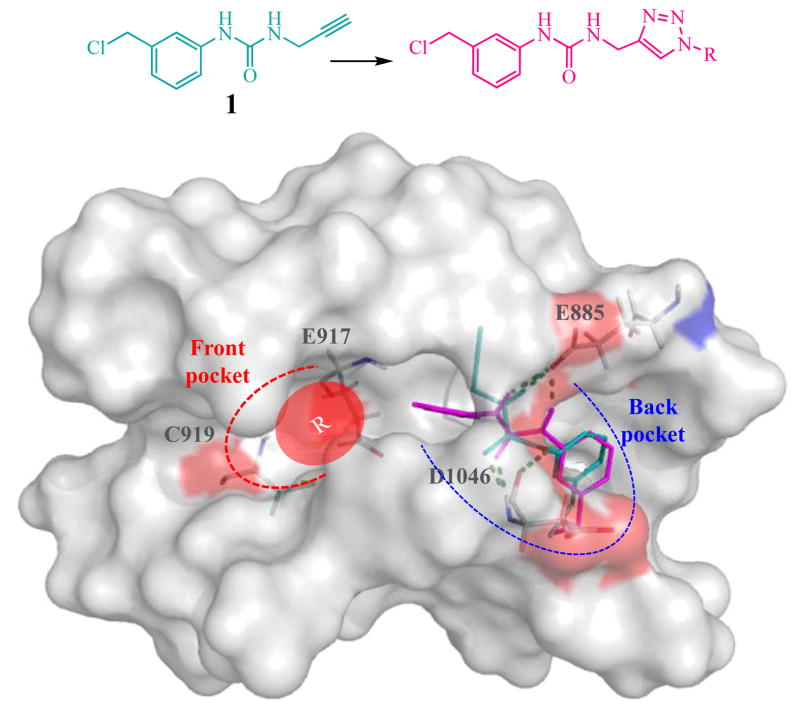

We previously discovered lead compound, 1-((3-chloro methyl) phenyl)-3-(2-propynyl)urea (1) with kinase inhibition against EGFR. The enzymatic inhibition against VEGFR-2 of this compound was not observed at the screening concentration (1 μM)22. In this work, we attempted to develop novel class of VEGFR-2 inhibitors using 1 as core structure, since docking simulation of 1 in active site of VEGFR-2 kinase revealed that this compound only occupied the allosteric site (Figure 2). Both urea HN moieties of 1 acted as hydrogen bond donors (HBD). One urea HN interacted with backbone carbonyl of Asp1046 while the other interacted with backbone carbonyl of Glu885. The urea carbonyl moiety of 1 also acted as hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) by interacting with backbone NH-amide of Asp1046. 3-Chloromethylphenyl substructure was found to bury in the hydrophobic back pocket and directed the terminal alkyne moiety to the front pocket. Based on this data, 1 was chosen as starting fragment in the development of novel VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitors.

Figure 2.

“Back to front” design strategy. 1 (blue) as starting motif buried in back pocket. Substituted group (R) on triazole to occupy the front pocket.

To design novel VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitors by back-to-front approach, we started from anchoring 1 in hydrophobic back pocket. 1 possesses terminal alkyne functional group which is a building block for 1,4-disubstituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles of which conveniently prepared by copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). Therefore, a virtual library of [1-(substituted)-1H-[1,2,3]-triazol-4-yl]-methyl-3-[3′-(chloromethyl)phenyl]ureas was designed by adding substituent (R group) on triazole linker. The design strategy is to extend the structure of phenylurea 1 by various substituents (R) that properly fit the front pocket and consequently increase the binding affinity.

The designed library of ninety [1-(substituted)-1H-[1,2,3]-triazol-4-yl]-methyl-3-[3′-(chloromethyl)phenyl]ureas was virtually screened by docking experiment. The detail of VEGFR-2 template preparation and validation were described in our previous work22. Briefly, the protein target was constructed from X-ray crystallographic structure of inactive VEGFR-2 (DFG-out conformation) in complex with K11 (PDB ID: 3EWH)1. The two missing loops were reconstructed (Super Looper Web Server23) before minimizing the energy (AMBER94 force field in MOE – Molecular Operating Environment – Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). Nonpolar hydrogens of new template 3EWHOK were merged before adding Gasteiger Huckel charges (AutoDockTools-1.5.224, 25). After that, types of atoms were assigned and grid representation of 3EWHOK was prepared (AutoGrid425). 3EWHOK template was validated by docking (AutoDock 4.2, TSRI)25 with the six active inhibitors: K11, AAX, GIG, LIF, 887 and 900 from PDB ID: 3EWH1, 1Y6B26, 2OH427, 1YWN28, 3B8R2 and 3B8Q2, respectively and all docked poses showed the same configuration as those in the corresponding crystal structures with RMSD less than 2 Å. These results indicated that 3EWHOK was a good VEGFR-2 model for in silico experiment.

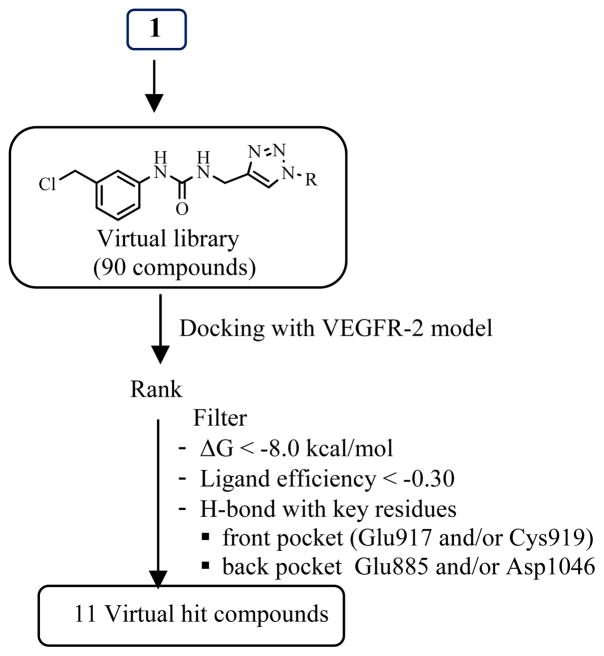

Virtual hit compounds were selected from the analysis of the docking result (Figure 3). The criteria for selecting hit compounds were free energy of binding (ΔG), hydrogen bonding interaction with key amino acid residues and the docked conformation by visual inspection. In addition to two hydrogen bondings between core urea HN and key residues in the back pocket, Asp1046 or Glu885, the virtual hit compounds must provide extra hydrogen bonding interaction with at least one of key residues in ATP-binding pocket either Glu917 or Cys919. The docking result of eleven virtual hit compounds was summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

In silico experiment to identify hit compounds.

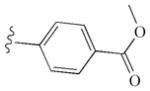

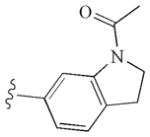

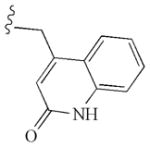

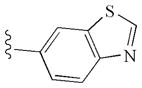

Table 1.

Selected virtual hit compounds for synthesis*

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cpd. | R | Free energy of binding (ΔG, kcal/mol) | H-bonding residues |

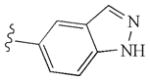

| VH01 |

|

−9.60 | Glu885, Glu885, Cys919, Asp1046 |

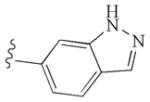

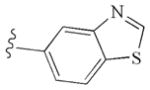

| VH02 |

|

−9.96 | Glu917, Cys919, Asp1046 |

| VH03 |

|

−10.13 | Glu885, Cys919, Asp1046 |

| VH04 |

|

−10.13 | Glu885, Glu885, Cys919, Asp1046 |

| VH05 |

|

−10.95 | Glu885, Glu885, Cys919, Asp1046 |

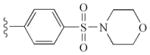

| VH06 |

|

−10.40 | Glu885, Glu885, Cys919, Asp1046 |

| VH07 |

|

−10.48 | Glu885, Cys919 |

| VH08 |

|

−10.65 | Glu885, Glu885, Cys919, Asp1046 |

| VH09 |

|

−10.42 | Glu885, Glu885, Cys919, Asp1046 |

| VH10 |

|

−10.04 | Cys919, Asp1046 |

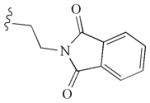

| VH11 |

|

−10.41 | Glu885, Glu885, |

Docking result of 1: binding energy was -6.47 kcal/mol; H-bonding residues were Glu885, Asp1046 and Asp1046.

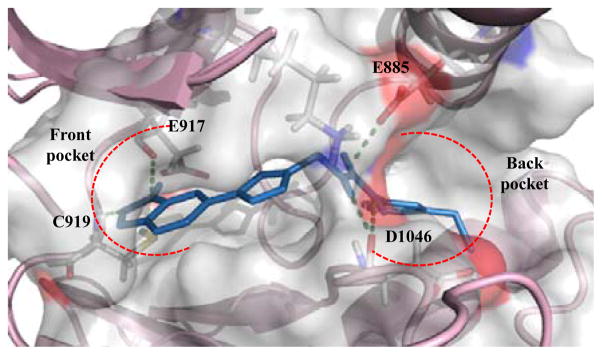

The hit compounds (VH01-VH11) showed notably lower binding energy comparing with compound 1 (Table 1). As anticipated, all compounds occupied both back and front pockets in similar manner. The phenylurea moiety buried in the hydrophobic back pocket and the substituted R extended to fit in the front pocket (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Model of VH02 (blue) bound to VEGFR-2 kinase domain (PDB code: 3EWHOK)1 showing 4 H-bond interactions in front and back pocket (green dotted line).

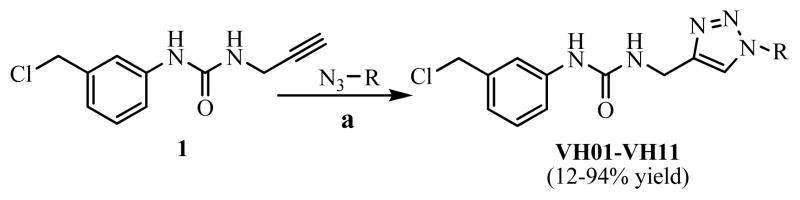

The selected virtual hit compounds were synthesized for biological testing. General synthesis procedure of 11 hit compounds was CuAAC reaction (Scheme 1). Briefly, equivalent mole of both 1 and corresponding azide building blocks were added into 25-ml round-bottom flask and suspended in t-BuOH:EtOH:H2O (2:1:1). Then 5 mol% of CuSO4 and 20 mol% of sodium ascorbate were added into the stirred reaction mixture and heated at 60° C for 1 or 2 hours. The forming precipitates were washed several times with cool ether before filtered. Pure products were collected as off-white to yellow powder. In some cases, pure products were purified by column chromatography on silica gel using 5–7% MeOH in dichloromethane as eluent (% unoptimized yield were 12–94%). All of the synthesized compounds were characterized by IR, NMR and by high-resolution mass spectroscopy. The assigned structures of all synthesized compounds were in agreement with the designed structures (supplementary data).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of selected virtual hit compounds by CuAAC reaction. (a) 5 mol% CuSO 4, 20 mol% Sodium ascorbate, t-BuOH:EtOH:H2O (1:1:2),

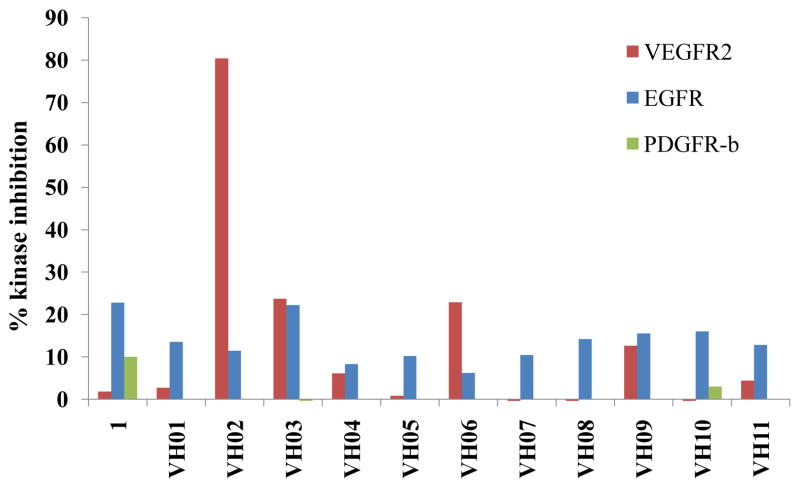

All synthesized compounds were then screened for their kinase inhibition at 1 μM against three kinds of RTKs including VEGFR-2, EGFR and PDGFR-β (Figure 5). The ability of compounds to inhibit the phosphorylation of a biotinylated polypeptide substrate were measured by previously described protocol22.

Figure 5.

Screening result at 1 μM of hit compounds against three tyrosine kinases.

At 1 μM screening concentration, VH02, the 6-indazolyl triazole derivative, was the only compound that remarkably inhibited the phosphorylation of VEGFR-2. The IC50 of VH02 against VEGFR-2 was determined and found to be 0.56 μM. Modest kinase inhibition against EGFR was observed in all synthesized compounds. Only 5-indazolyl triazole (VH03) retained the activity against EGFR in the same level as 1 while the other extended triazoles led to the diminished potency against this tyrosine kinase. Inhibition against PDGFR-β was not observed in all compounds. VH02 from in silico screening was considered as novel lead of VEGFR-2 inhibitor.

The kinase inhibitory activity of VH02 against VEGFR-2 can be explained by its binding mode from molecular modeling. Though the binding energy of VH02 was not significantly different from other hit compounds, the H-bonding interaction between VH02 and key residues in the front pocket of VEGFR-2 kinase was different from the others. The 6-indazolyl substructure of VH02 formed two hydrogen bond interactions with the key residues, Glu917 and Cys919, in the front pocket of VEGFR-2 kinase while the corresponding triazole substructures (R) of other hit compounds formed only one H-bonding with Cys919, key residue in the front pocket. The extra H-bonding between VH02 and key residues observed in the front pocket of VEGFR-2 help explaining the activity of VH02 over other hit compounds. In total, VH02 formed five H-bond interaction with key amino acids in the binding site of VEGFR-2 kinase. The indazolyl NH acted as HBD forming one hydrogen bond with backbone carbonyl of Glu917, while the N-2 indazole acted as HBA forming H-bonding with backbone NH of Cys919. Aromatic part of indazole ring interacted with hydrophobic region within the front pocket. This area composed of side chains of Leu840, Val848, Ala866, Lys868, Glu917 Phe918 and Gly922. Triazole linker of VH02 participated in one H-bond interaction using N-2 triazole as HBA to interact with the side chain NH of Lys868. Urea moiety formed two hydrogen bonds with key residues in the back pocket of VEGFR-2 kinase. Both urea HN formed H-bonding with the same backbone carbonyl of Asp1046. Substituted phenyl motif of VH02 buried in the hydrophobic part of the back pocket and interacted with the side chains of Ile888, Ile892, Val898, Val899, Leu1019, His1026, Ile1044, Cys1045 and Phe1047. The hydrophobic interactions both in the front and allosteric pocket moderate the binding affinity and selectivity by stabilizing the proper conformation of the compound in the binding site of the VEGFR-2 kinase. The poor activity of VH02 against EGFR might be caused by the unfit of the 6-indazolyl substructure in the active site of EGFR kinase. In silico study between VH02 and active site of EGFR (PDB ID: 1M17) was performed and the result supported our expectation (data not showed). Though the 6-indazolyl substructure expanded the overall structure of the compound to occupy both front and back pocket, the structure is more rigid and showed different conformation when compared with erlotinib in the active binding site of EGFR.

VH02 was further evaluated for the antiangiogenic effect, this compound was firstly screened for it antiproliferative activity in the immortal HUVECs (EA.hy926) which frequently used in the in vitro angiogenesis testing model29–31. The protocol for the antiproliferation assay was previously described22.

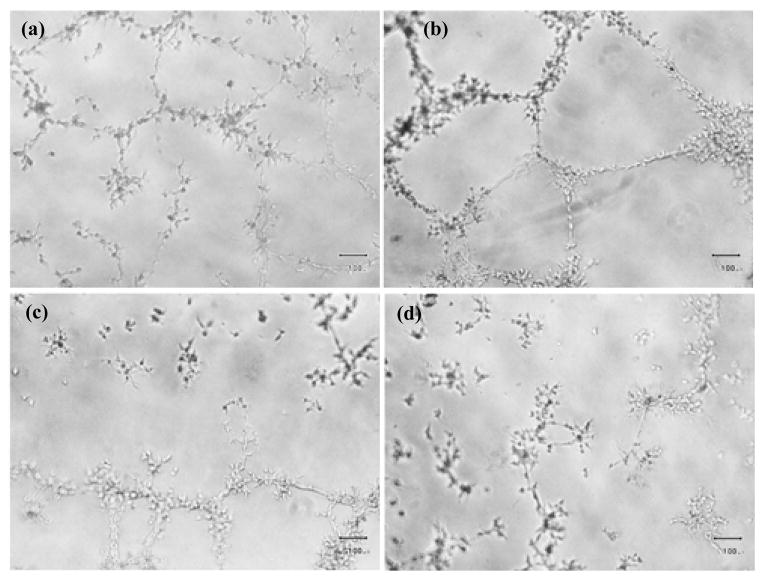

The IC50 cytotoxic effect against EA.hy926 of VH02 was 4 μM. The in vitro antiangiogenic effect of VH02 was evaluated by tube formation assay, the test was performed at the non-cytotoxic concentration to avoid false positive from the cytotoxic effect. The results from tube formation assay were shown in Figure 6. VH02 significantly inhibited tube formation at 0.3 μM which was 13 times lower than its cytotoxic IC50 against EA.hy926.

Figure 6.

Effect of VH02 on VEGF-stimulated tube formation at 10X magnification. (a) 0.1% DMSO (b) control with VEGF 25 ng/ml (c) and (d) treatment with VH02 0.3 μM and 1.0 μM, respectively.

Moreover, the antiproliferative activity of VH02 was investigated in four other cancer cells including cervical cancer (HELA), human breast cancer (MCF-7), large cell lung cancer (H460) and hepatic carcinoma (HepG2). The result was summarized in Table 2. The antiproliferative result indicated that VH02 selectively inhibited EA.hy 926 which represented vascular endothelial cells with weak cytotoxicity against other cancer cells. Thus, this compound may be useful in the treatment of cancer to avoid metastasis as well as to prolong recurrent time with low toxicity.

Table 2.

Antiproliferative effect of VH02 on cancer cells and EA.hy 926

| Type of cancer cells | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| HELA | 33 |

| MCF-7 | 21 |

| H460 | 71 |

| HepG2 | > 100 |

| EA.hy 926 | 4 |

In conclusion, VH02 was successfully developed as novel lead of VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitor by back-to-front approach starting from 3-(3′-chloromethylphenyl)urea fragment. Triazole ring was used as linker in the design process due to its convenience in synthesis by CuAAC reaction. The enzymatic and cellular activity demonstrated that this compound was antiangiogenic agent that selectively inhibited VEGFR-2. VH02 can be considered as promising lead with novel scaffold which suitable for further optimization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program (RGJ Grant No. PHD/0229/2547) funded by Thailand Research Fund (TRF) and the commission of Higher Education Thailand (CHE-RG 2551).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:.

References and notes

- 1.Cee VJ, Cheng AC, Romero K, Bellon S, Mohr C, Whittington DA, Bak A, Bready J, Caenepeel S, Coxon A, Deak HL, Fretland J, Gu Y, Hodous BL, Huang X, Kim JL, Lin J, Long AM, Nguyen H, Olivieri PR, Patel VF, Wang L, Zhou Y, Hughes P, Geuns-Meyer S. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:424. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss MM, Harmange JC, Polverino AJ, Bauer D, Berry L, Berry V, Borg G, Bready J, Chen D, Choquette D, Coxon A, DeMelfi T, Doerr N, Estrada J, Flynn J, Graceffa RF, harriman SP, Kaufman S, La DS, Long A, Neervannan S, Patel VF, Potashman M, Regal K, Roveto PM, Schrag ML, Starnes C, Tasker A, Teffera Y, Whittington DA, Zanon R. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1668. doi: 10.1021/jm701098w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zwick E, Bange J, Ullrich A. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:17. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culhane J, Li E. US Pharmacist. 2008;33:3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folkman J. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:15. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:549. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schenone S, Bondavalli F, Botta M. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2495. doi: 10.2174/092986707782023622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes K, Roberts OL, Thomas AM, Cross MJ. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2003. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Gray NS. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:358. doi: 10.1038/nchembio799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:28. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okram B, Nagel A, Adrian FJ, Lee C, Ren P, Wang X, Sim T, Xie Y, Wang X, Xia G, Spraggon G, Warmuth M, Leu Y, Gray NS. J Chem Biol. 2006;13:779. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuccotto F, Ardini E, Casale E, Angiolini M. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2681. doi: 10.1021/jm901443h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kufareva I, Abagyan R. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7921. doi: 10.1021/jm8010299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie QQ, Xie HZ, Ren JX, Li LL, Yang SY. J Mol Graph Model. 2009;27:751. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz PA, Murray BW. Bioorg Chem. 2011;39:192. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer D, Whittington DA, Coxon A, Bready J, Harriman SP, Patel VF, Polverino A, Harmange JC. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:4844. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda T, Nagahara H, Mogi H, Ban M, Aono H. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1782. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sammond DM, Nailor KE, Veal JM, Nolte RT, Wang L, Knick VB, Rudolph SK, Truesdale AT, Nartey EN, Stafford JA, Kumar R, Cheung M. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:3519. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regan J, Breitfelder S, Cirillo P, Gilmore T, Graham AG, Hickey E, Klaus B, Madwed J, Moriak M, Moss N, Pargellis C, Pav S, Proto A, Swinamer A, Tong L, Torcellini C. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2994. doi: 10.1021/jm020057r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldwin I, Bamborough P, Haslam CG, Hunjan SS, Longstaff T, Mooney CJ, Patel S, Quinn J, Somers DO. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5285. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwata H, Oki H, Okada K, Takagi T, Tawada M, Miyazaki Y, Imamura S, Hori A, Lawson JD, Hixon MS, Kimura H, Miki H. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2012 doi: 10.1021/ml3000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanphanya K, Wattanapitayakul SK, Prangsaengtong O, Jo M, Koizumi K, Shibahara N, Priprem A, Fokin VV, Vajragupta O. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hildebrand PW, Goede A, Bauer RA, Gruening B, Ismer J, Michalsky E, Preissner R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forli S, Botta M. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1481. doi: 10.1021/ci700036j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris PA, Cheung M, Hunter RN, Brown ML, Veal JM, Nolte RT, Wang L, Liu W, Crosby RM, Johnson JH, Epperly AH, Kumar R, Luttrell DK, Stafford JA. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1610. doi: 10.1021/jm049538w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa M, Nishigaki N, Washio Y, Kano K, Harris PA, Sato H, Mori I, West RI, Shibahara M, Toyoda H, Wang L, Nolte RT, Veal JM, Cheung M. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4453. doi: 10.1021/jm0611051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazaki Y, Matsunaga S, Tang J, Maeda Y, Nakano M, Philippe RJ, Shibahara M, Liu W, Sato H, Wang L, Nolte RT. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2203. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu H-T, Lin S-h, Chen Y-H. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5164. doi: 10.1021/jf050034w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cong M, Xue-chun L, Yun L, Jian C, Bo Y, Yan G, Xian-feng L, Li F. Chin Med J. 2012;125:1369. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones MK, Sarfeh IJ, Tarnawski AS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:118. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.